Instruction Set Architecture COE 301 Computer Organization ICS

![Example on Load & Store v Translate A[1] = A[2] + 5 (A is Example on Load & Store v Translate A[1] = A[2] + 5 (A is](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/1df6014b6311ca484813b73f9cafe9a4/image-42.jpg)

- Slides: 57

Instruction Set Architecture COE 301 Computer Organization ICS 233 Computer Architecture and Assembly Language Dr. Marwan Abu-Amara College of Computer Sciences and Engineering King Fahd University of Petroleum and Minerals [Adapted from slides of Dr. M. Mudawar and Dr. A. El-Maleh, KFUPM]

Outline v Instruction Set Architecture v Overview of the MIPS Processor v R-Type Arithmetic, Logical, and Shift Instructions v I-Type Format and Immediate Constants v Jump and Branch Instructions v Translating If Statements and Boolean Expressions v Load and Store Instructions v Translating Loops and Traversing Arrays v Addressing Modes Instruction Set Architecture COE 301 – Computer Organization – KFUPM © Muhamed Mudawar slide 2

Instruction Set Architecture (ISA) v Critical interface between hardware and software v An ISA includes the following … ² Instructions and Instruction Formats § Data Types, Encodings, and Representations § Addressing Modes: to address Instructions and Data § Handling Exceptional Conditions (like division by zero) ² Programmable Storage: Registers and Memory v Examples (Versions) First Introduced in ² Intel (8086, 80386, Pentium, . . . ) 1978 ² MIPS (MIPS I, III, IV, V) 1986 ² Power. PC (601, 604, …) 1993 Instruction Set Architecture COE 301 – Computer Organization – KFUPM © Muhamed Mudawar slide 3

Instructions v Instructions are the language of the machine v We will study the MIPS instruction set architecture ² Known as Reduced Instruction Set Computer (RISC) ² Elegant and relatively simple design ² Similar to RISC architectures developed in mid-1980’s and 90’s ² Very popular, used in many products § Silicon Graphics, ATI, Cisco, Sony, etc. ² Comes next in sales after Intel IA-32 processors § Almost 100 million MIPS processors sold in 2002 (and increasing) v Alternative design: Intel IA-32 ² Known as Complex Instruction Set Computer (CISC) Instruction Set Architecture COE 301 – Computer Organization – KFUPM © Muhamed Mudawar slide 4

Next. . . v Instruction Set Architecture v Overview of the MIPS Processor v R-Type Arithmetic, Logical, and Shift Instructions v I-Type Format and Immediate Constants v Jump and Branch Instructions v Translating If Statements and Boolean Expressions v Load and Store Instructions v Translating Loops and Traversing Arrays v Addressing Modes Instruction Set Architecture COE 301 – Computer Organization – KFUPM © Muhamed Mudawar slide 5

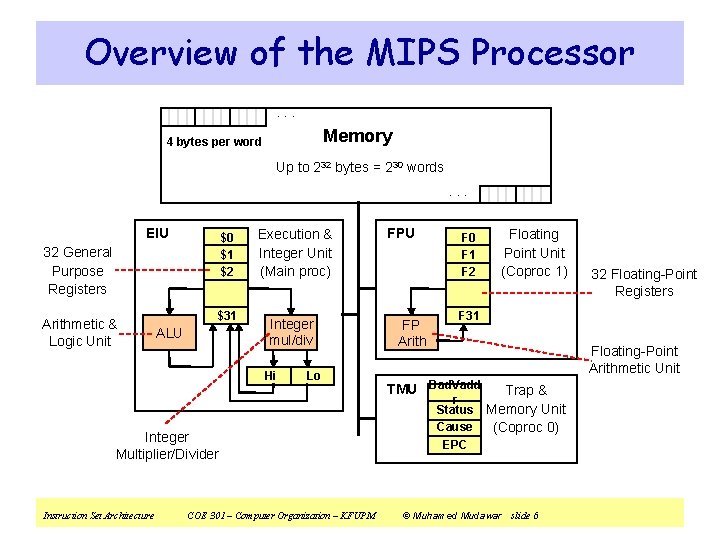

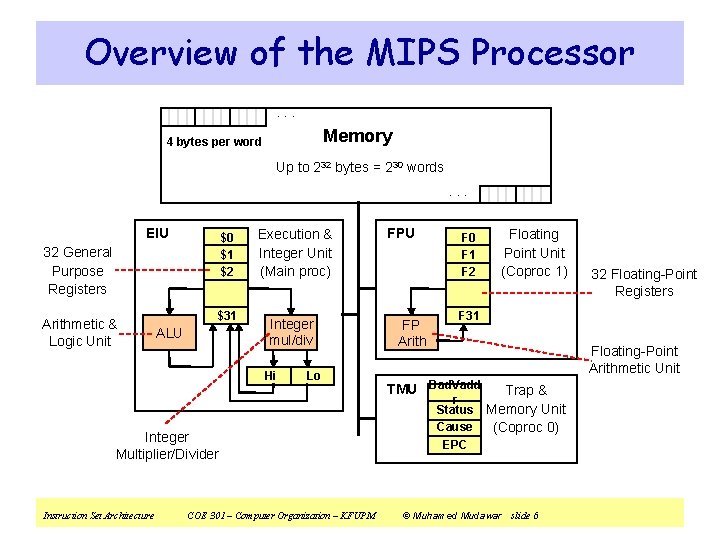

Overview of the MIPS Processor. . . Memory 4 bytes per word Up to 232 bytes = 230 words. . . EIU $0 $1 $2 32 General Purpose Registers Arithmetic & Logic Unit $31 ALU Execution & Integer Unit (Main proc) Integer mul/div Hi Lo Integer Multiplier/Divider Instruction Set Architecture COE 301 – Computer Organization – KFUPM FPU FP Arith F 0 F 1 F 2 Floating Point Unit (Coproc 1) 32 Floating-Point Registers F 31 Floating-Point Arithmetic Unit TMU Bad. Vadd r Status Cause EPC Trap & Memory Unit (Coproc 0) © Muhamed Mudawar slide 6

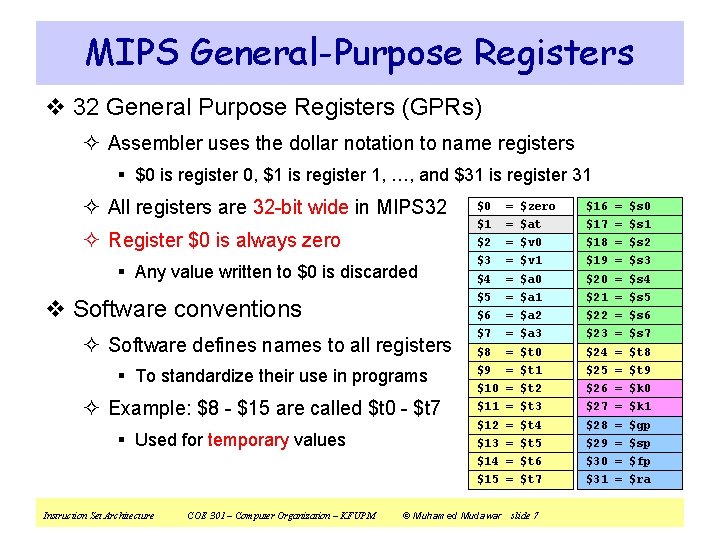

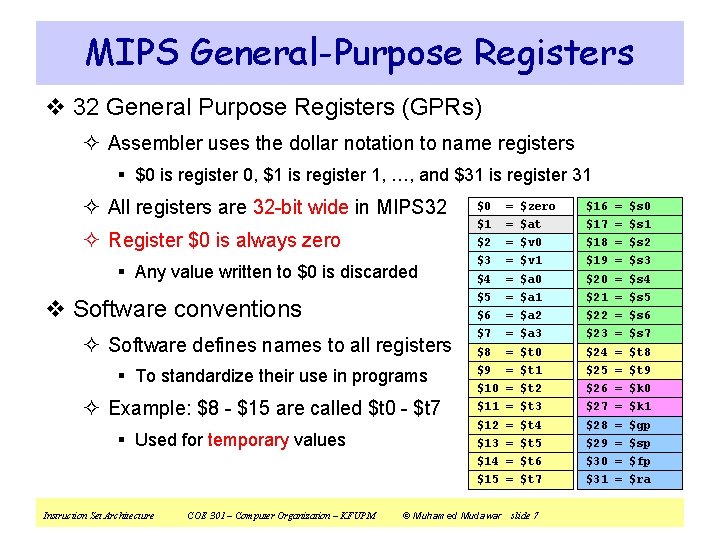

MIPS General-Purpose Registers v 32 General Purpose Registers (GPRs) ² Assembler uses the dollar notation to name registers § $0 is register 0, $1 is register 1, …, and $31 is register 31 ² All registers are 32 -bit wide in MIPS 32 $0 = $zero $16 = $s 0 ² Register $0 is always zero $1 = $at $17 = $s 1 $2 = $v 0 $18 = $s 2 $3 = $v 1 $19 = $s 3 $4 = $a 0 $20 = $s 4 $5 = $a 1 $21 = $s 5 $6 = $a 2 $22 = $s 6 $7 = $a 3 $23 = $s 7 $8 = $t 0 $24 = $t 8 $9 = $t 1 $25 = $t 9 $10 = $t 2 $26 = $k 0 $11 = $t 3 $27 = $k 1 $12 = $t 4 $28 = $gp $13 = $t 5 $29 = $sp $14 = $t 6 $30 = $fp $15 = $t 7 $31 = $ra § Any value written to $0 is discarded v Software conventions ² Software defines names to all registers § To standardize their use in programs ² Example: $8 - $15 are called $t 0 - $t 7 § Used for temporary values Instruction Set Architecture COE 301 – Computer Organization – KFUPM © Muhamed Mudawar slide 7

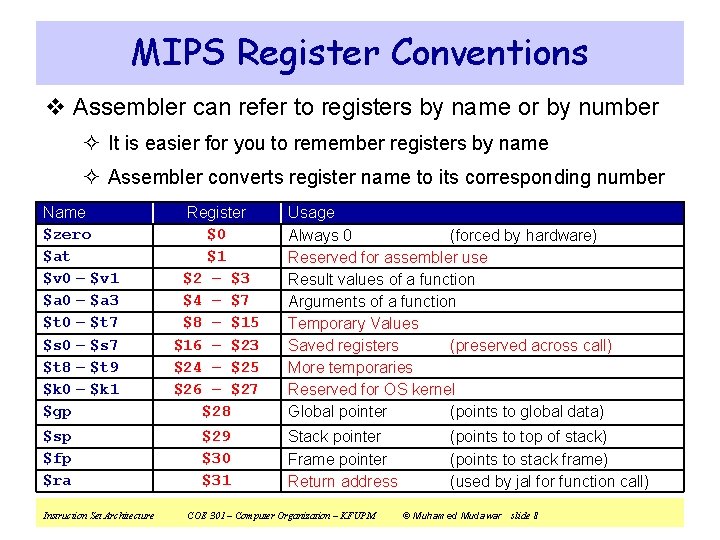

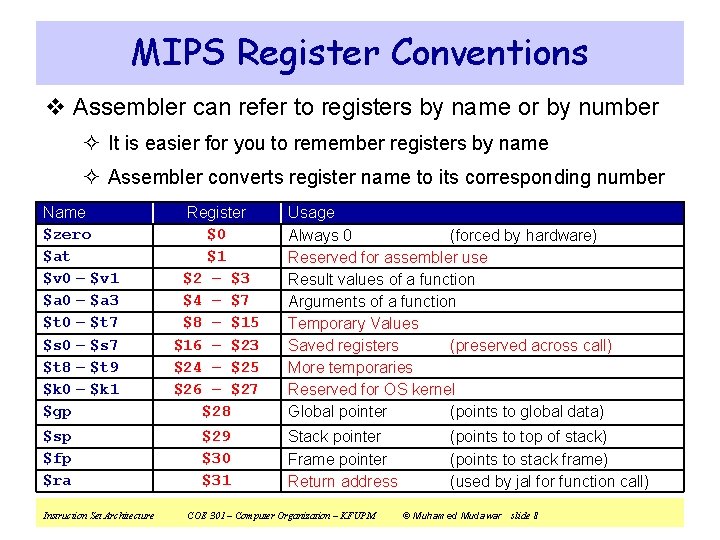

MIPS Register Conventions v Assembler can refer to registers by name or by number ² It is easier for you to remember registers by name ² Assembler converts register name to its corresponding number Name $zero $at $v 0 – $v 1 $a 0 – $a 3 $t 0 – $t 7 $s 0 – $s 7 $t 8 – $t 9 $k 0 – $k 1 $gp $sp $fp $ra Instruction Set Architecture Register $0 $1 $2 – $3 $4 – $7 $8 – $15 $16 – $23 $24 – $25 $26 – $27 $28 $29 $30 $31 Usage Always 0 (forced by hardware) Reserved for assembler use Result values of a function Arguments of a function Temporary Values Saved registers (preserved across call) More temporaries Reserved for OS kernel Global pointer (points to global data) Stack pointer Frame pointer Return address COE 301 – Computer Organization – KFUPM (points to top of stack) (points to stack frame) (used by jal for function call) © Muhamed Mudawar slide 8

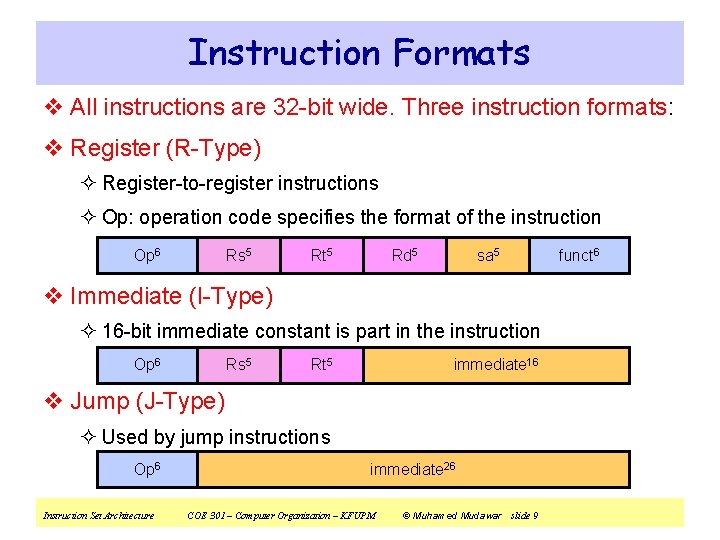

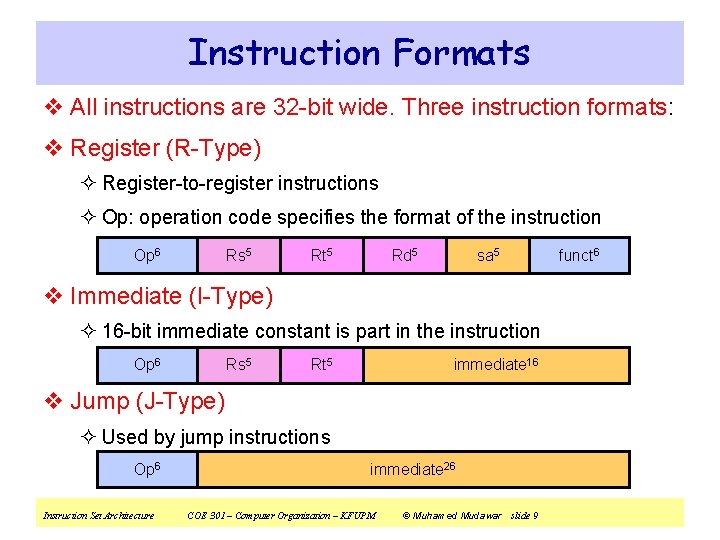

Instruction Formats v All instructions are 32 -bit wide. Three instruction formats: v Register (R-Type) ² Register-to-register instructions ² Op: operation code specifies the format of the instruction Op 6 Rs 5 Rt 5 Rd 5 sa 5 v Immediate (I-Type) ² 16 -bit immediate constant is part in the instruction Op 6 Rs 5 Rt 5 immediate 16 v Jump (J-Type) ² Used by jump instructions Op 6 Instruction Set Architecture immediate 26 COE 301 – Computer Organization – KFUPM © Muhamed Mudawar slide 9 funct 6

Instruction Categories v Integer Arithmetic ² Arithmetic, logical, and shift instructions v Data Transfer ² Load and store instructions that access memory ² Data movement and conversions v Jump and Branch ² Flow-control instructions that alter the sequential sequence v Floating Point Arithmetic ² Instructions that operate on floating-point registers v Miscellaneous ² Instructions that transfer control to/from exception handlers ² Memory management instructions Instruction Set Architecture COE 301 – Computer Organization – KFUPM © Muhamed Mudawar slide 10

Next. . . v Instruction Set Architecture v Overview of the MIPS Processor v R-Type Arithmetic, Logical, and Shift Instructions v I-Type Format and Immediate Constants v Jump and Branch Instructions v Translating If Statements and Boolean Expressions v Load and Store Instructions v Translating Loops and Traversing Arrays v Addressing Modes Instruction Set Architecture COE 301 – Computer Organization – KFUPM © Muhamed Mudawar slide 11

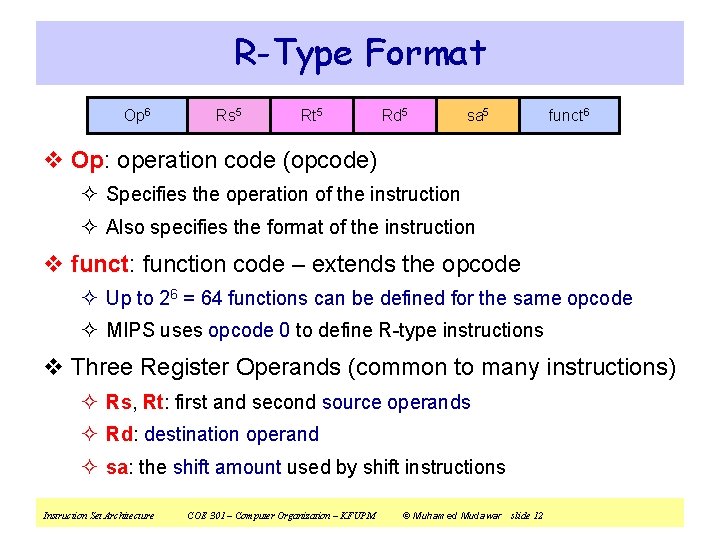

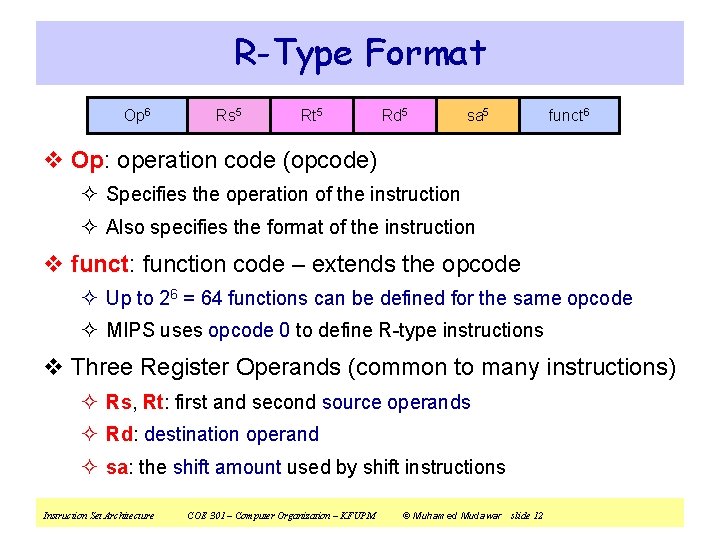

R-Type Format Op 6 Rs 5 Rt 5 Rd 5 sa 5 funct 6 v Op: operation code (opcode) ² Specifies the operation of the instruction ² Also specifies the format of the instruction v funct: function code – extends the opcode ² Up to 26 = 64 functions can be defined for the same opcode ² MIPS uses opcode 0 to define R-type instructions v Three Register Operands (common to many instructions) ² Rs, Rt: first and second source operands ² Rd: destination operand ² sa: the shift amount used by shift instructions Instruction Set Architecture COE 301 – Computer Organization – KFUPM © Muhamed Mudawar slide 12

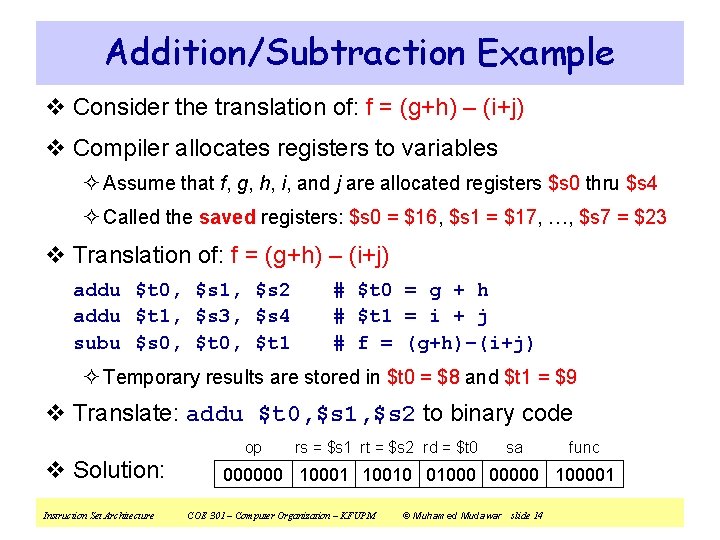

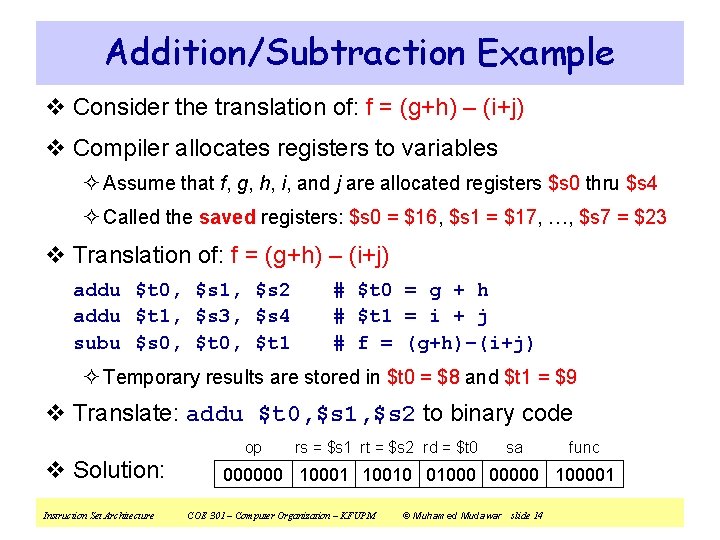

Integer Add /Subtract Instructions Instruction addu subu $s 1, $s 2, $s 3 Meaning $s 1 = $s 2 + $s 3 $s 1 = $s 2 – $s 3 R-Type Format op = 0 rs = $s 2 rt = $s 3 rd = $s 1 sa = 0 f = 0 x 20 f = 0 x 21 f = 0 x 22 f = 0 x 23 v add & sub: overflow causes an arithmetic exception ² In case of overflow, result is not written to destination register v addu & subu: same operation as add & sub ² However, no arithmetic exception can occur ² Overflow is ignored v Many programming languages ignore overflow ² The + operator is translated into addu ² The – operator is translated into subu Instruction Set Architecture COE 301 – Computer Organization – KFUPM © Muhamed Mudawar slide 13

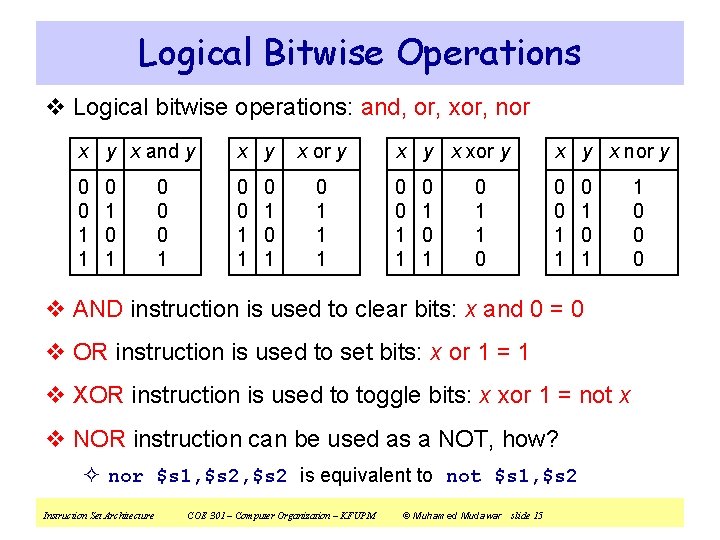

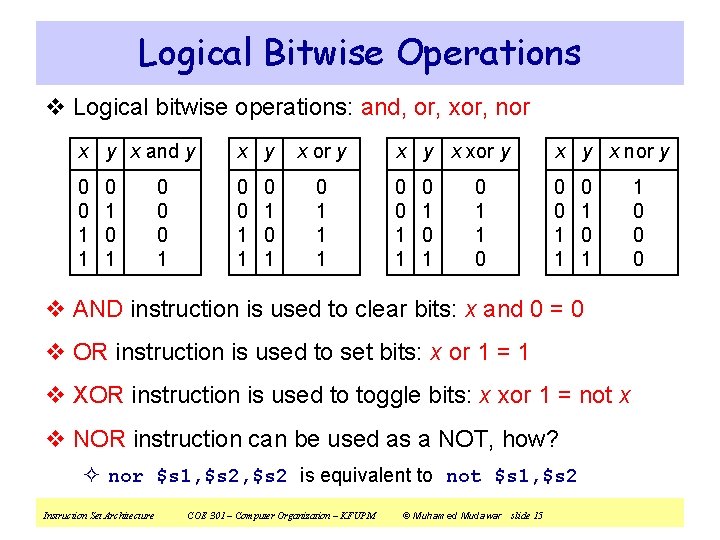

Addition/Subtraction Example v Consider the translation of: f = (g+h) – (i+j) v Compiler allocates registers to variables ² Assume that f, g, h, i, and j are allocated registers $s 0 thru $s 4 ² Called the saved registers: $s 0 = $16, $s 1 = $17, …, $s 7 = $23 v Translation of: f = (g+h) – (i+j) addu $t 0, $s 1, $s 2 addu $t 1, $s 3, $s 4 subu $s 0, $t 1 # $t 0 = g + h # $t 1 = i + j # f = (g+h)–(i+j) ² Temporary results are stored in $t 0 = $8 and $t 1 = $9 v Translate: addu $t 0, $s 1, $s 2 to binary code op v Solution: Instruction Set Architecture rs = $s 1 rt = $s 2 rd = $t 0 sa func 000000 10001 10010 01000 00000 100001 COE 301 – Computer Organization – KFUPM © Muhamed Mudawar slide 14

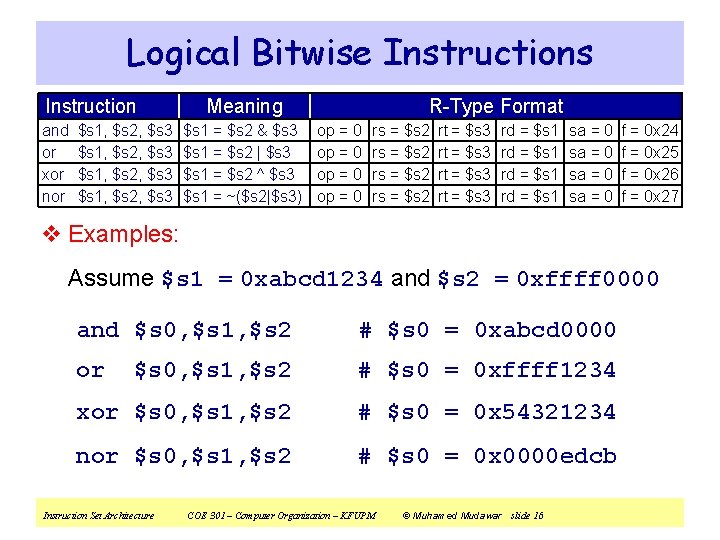

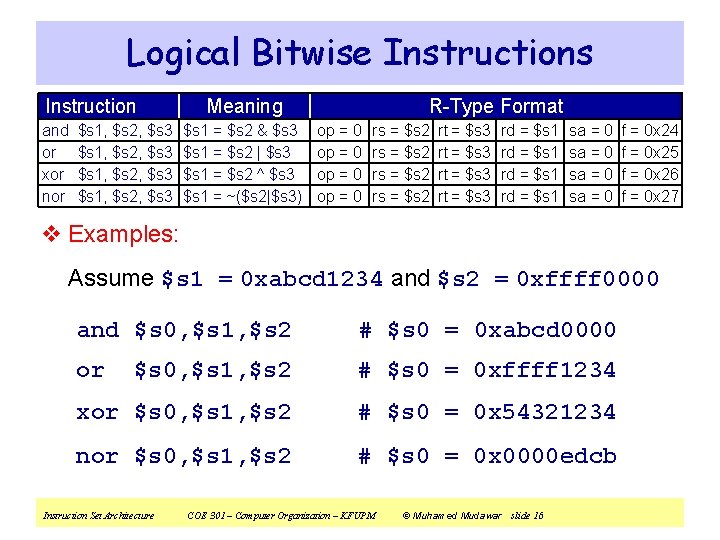

Logical Bitwise Operations v Logical bitwise operations: and, or, xor, nor x y x and y x y 0 0 1 1 0 1 0 0 0 1 0 1 x or y 0 1 1 1 x y x xor y x nor y 0 0 1 1 0 1 0 1 1 0 0 1 v AND instruction is used to clear bits: x and 0 = 0 v OR instruction is used to set bits: x or 1 = 1 v XOR instruction is used to toggle bits: x xor 1 = not x v NOR instruction can be used as a NOT, how? ² nor $s 1, $s 2 is equivalent to not $s 1, $s 2 Instruction Set Architecture COE 301 – Computer Organization – KFUPM © Muhamed Mudawar slide 15 1 0 0 0

Logical Bitwise Instructions Instruction and or xor nor $s 1, $s 2, $s 3 Meaning $s 1 = $s 2 & $s 3 $s 1 = $s 2 | $s 3 $s 1 = $s 2 ^ $s 3 $s 1 = ~($s 2|$s 3) R-Type Format op = 0 rs = $s 2 rt = $s 3 rd = $s 1 sa = 0 f = 0 x 24 f = 0 x 25 f = 0 x 26 f = 0 x 27 v Examples: Assume $s 1 = 0 xabcd 1234 and $s 2 = 0 xffff 0000 and $s 0, $s 1, $s 2 # $s 0 = 0 xabcd 0000 or $s 0, $s 1, $s 2 # $s 0 = 0 xffff 1234 xor $s 0, $s 1, $s 2 # $s 0 = 0 x 54321234 nor $s 0, $s 1, $s 2 # $s 0 = 0 x 0000 edcb Instruction Set Architecture COE 301 – Computer Organization – KFUPM © Muhamed Mudawar slide 16

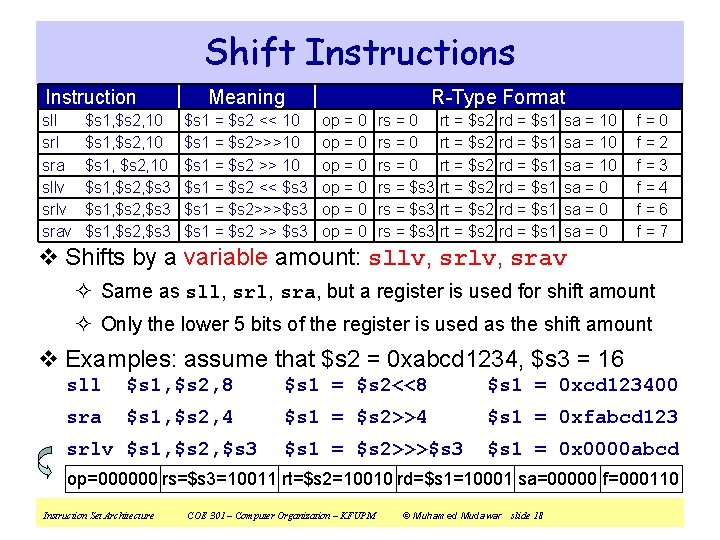

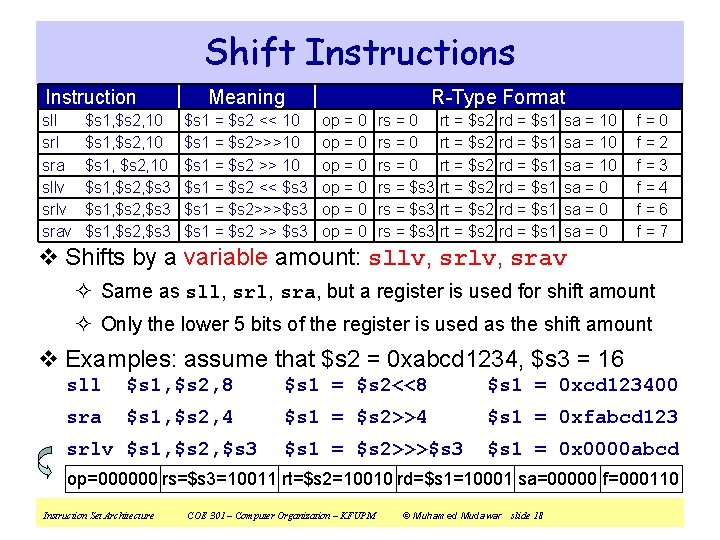

Shift Operations v Shifting is to move all the bits in a register left or right v Shifts by a constant amount: sll, sra ² sll means shift left logical (insert zero from the right) ² srl means shift right logical (insert zero from the left) ² sra means shift right arithmetic (insert sign-bit) ² The 5 -bit shift amount field is used by these instructions sll shift-out MSB srl shift-in 0 sra shift-in sign-bit Instruction Set Architecture 32 -bit register . . . shift-in 0 . . . shift-out LSB COE 301 – Computer Organization – KFUPM © Muhamed Mudawar slide 17

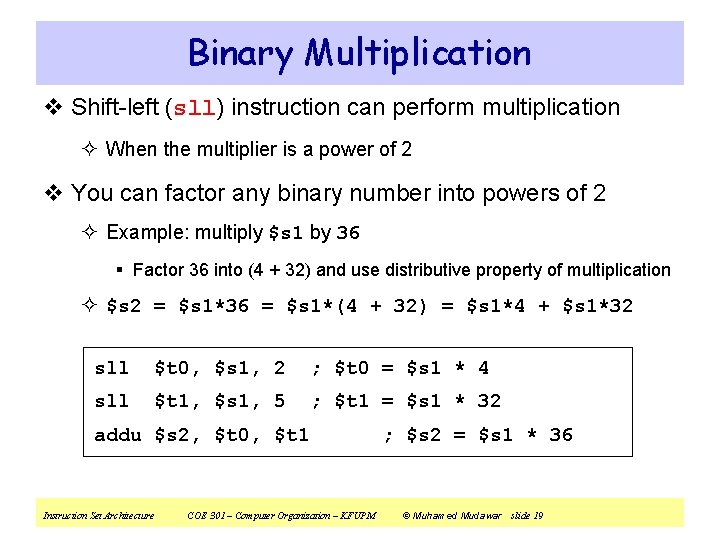

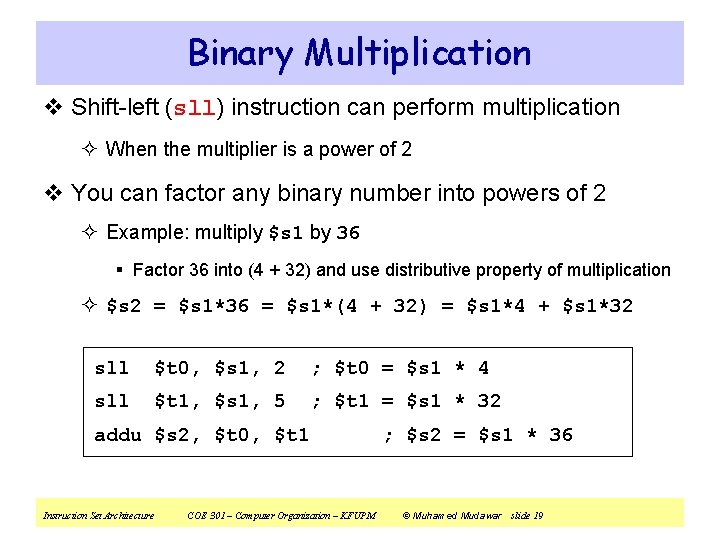

Shift Instructions Instruction sll sra sllv srav $s 1, $s 2, 10 $s 1, $s 2, $s 3 Meaning $s 1 = $s 2 << 10 $s 1 = $s 2>>>10 $s 1 = $s 2 >> 10 $s 1 = $s 2 << $s 3 $s 1 = $s 2>>>$s 3 $s 1 = $s 2 >> $s 3 R-Type Format op = 0 op = 0 rs = 0 rt = $s 2 rs = $s 3 rt = $s 2 rd = $s 1 rd = $s 1 sa = 10 sa = 0 f=2 f=3 f=4 f=6 f=7 v Shifts by a variable amount: sllv, srav ² Same as sll, sra, but a register is used for shift amount ² Only the lower 5 bits of the register is used as the shift amount v Examples: assume that $s 2 = 0 xabcd 1234, $s 3 = 16 sll $s 1, $s 2, 8 $s 1 = $s 2<<8 $s 1 = 0 xcd 123400 sra $s 1, $s 2, 4 $s 1 = $s 2>>4 $s 1 = 0 xfabcd 123 $s 1 = $s 2>>>$s 3 $s 1 = 0 x 0000 abcd srlv $s 1, $s 2, $s 3 op=000000 rs=$s 3=10011 rt=$s 2=10010 rd=$s 1=10001 sa=00000 f=000110 Instruction Set Architecture COE 301 – Computer Organization – KFUPM © Muhamed Mudawar slide 18

Binary Multiplication v Shift-left (sll) instruction can perform multiplication ² When the multiplier is a power of 2 v You can factor any binary number into powers of 2 ² Example: multiply $s 1 by 36 § Factor 36 into (4 + 32) and use distributive property of multiplication ² $s 2 = $s 1*36 = $s 1*(4 + 32) = $s 1*4 + $s 1*32 sll $t 0, $s 1, 2 ; $t 0 = $s 1 * 4 sll $t 1, $s 1, 5 ; $t 1 = $s 1 * 32 addu $s 2, $t 0, $t 1 Instruction Set Architecture COE 301 – Computer Organization – KFUPM ; $s 2 = $s 1 * 36 © Muhamed Mudawar slide 19

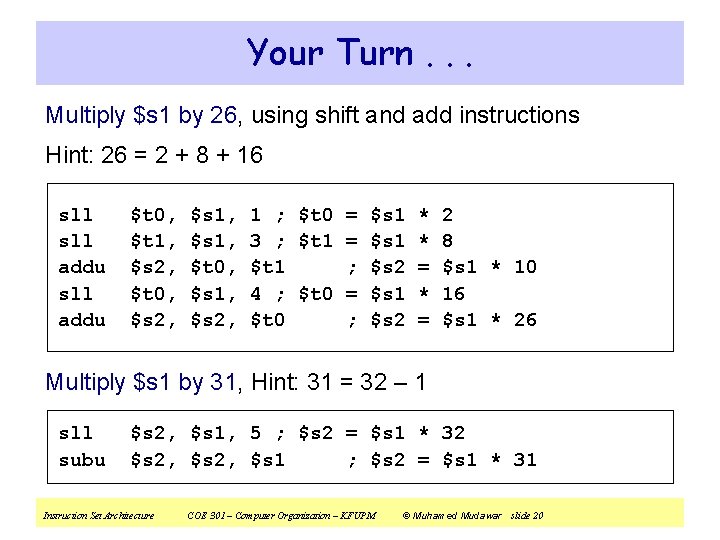

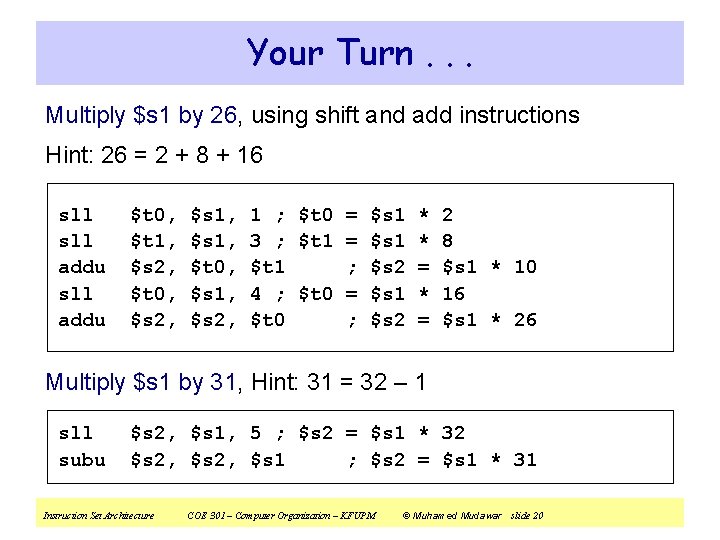

Your Turn. . . Multiply $s 1 by 26, using shift and add instructions Hint: 26 = 2 + 8 + 16 sll addu $t 0, $t 1, $s 2, $t 0, $s 2, $s 1, $t 0, $s 1, $s 2, 1 ; $t 0 = $s 1 * 2 3 ; $t 1 = $s 1 * 8 $t 1 ; $s 2 = $s 1 * 10 4 ; $t 0 = $s 1 * 16 $t 0 ; $s 2 = $s 1 * 26 Multiply $s 1 by 31, Hint: 31 = 32 – 1 sll subu $s 2, $s 1, 5 ; $s 2 = $s 1 * 32 $s 2, $s 1 ; $s 2 = $s 1 * 31 Instruction Set Architecture COE 301 – Computer Organization – KFUPM © Muhamed Mudawar slide 20

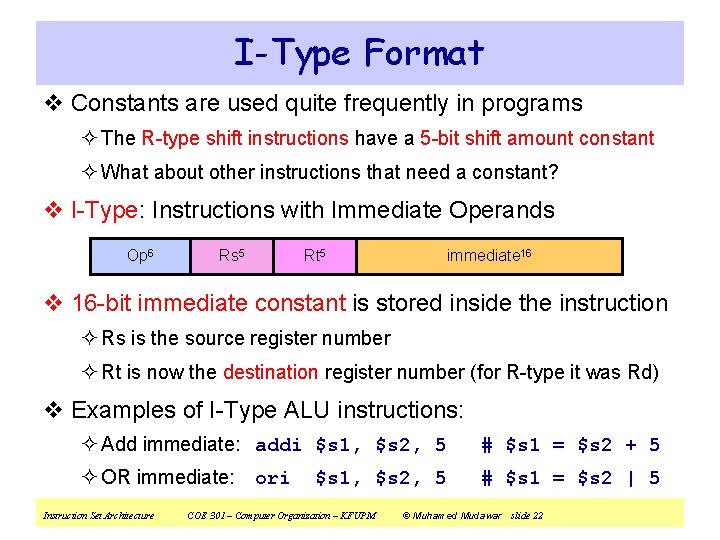

Next. . . v Instruction Set Architecture v Overview of the MIPS Processor v R-Type Arithmetic, Logical, and Shift Instructions v I-Type Format and Immediate Constants v Jump and Branch Instructions v Translating If Statements and Boolean Expressions v Load and Store Instructions v Translating Loops and Traversing Arrays v Addressing Modes Instruction Set Architecture COE 301 – Computer Organization – KFUPM © Muhamed Mudawar slide 21

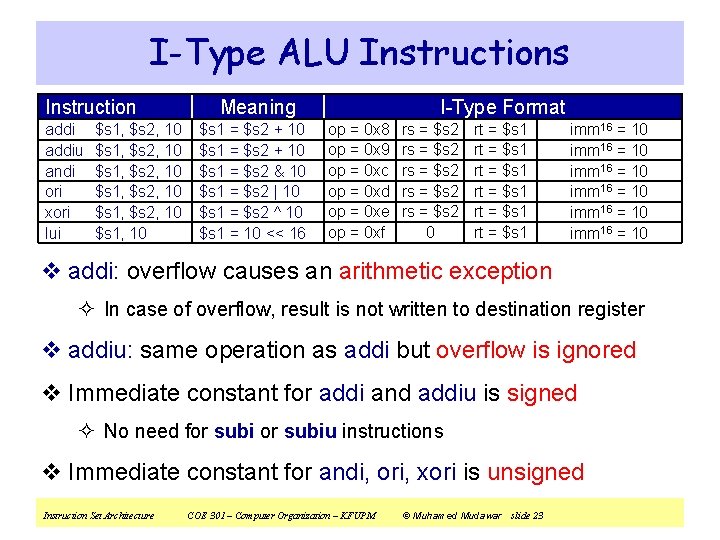

I-Type Format v Constants are used quite frequently in programs ² The R-type shift instructions have a 5 -bit shift amount constant ² What about other instructions that need a constant? v I-Type: Instructions with Immediate Operands Op 6 Rs 5 Rt 5 immediate 16 v 16 -bit immediate constant is stored inside the instruction ² Rs is the source register number ² Rt is now the destination register number (for R-type it was Rd) v Examples of I-Type ALU instructions: ² Add immediate: addi $s 1, $s 2, 5 # $s 1 = $s 2 + 5 ² OR immediate: # $s 1 = $s 2 | 5 Instruction Set Architecture ori $s 1, $s 2, 5 COE 301 – Computer Organization – KFUPM © Muhamed Mudawar slide 22

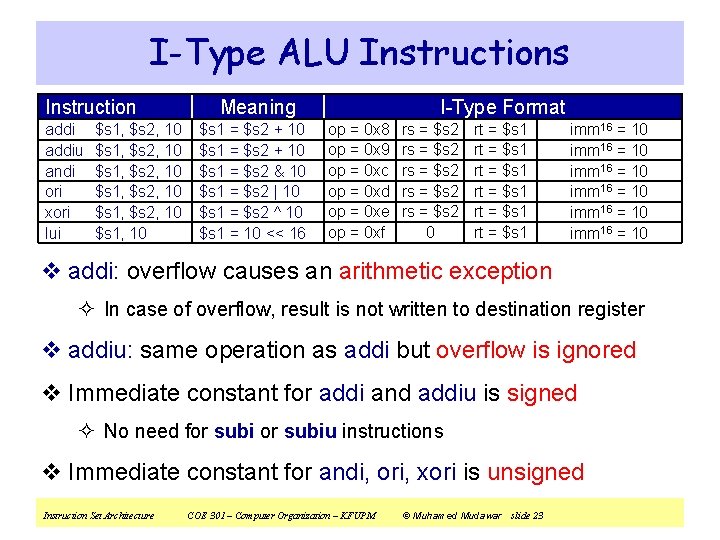

I-Type ALU Instructions Instruction addiu andi ori xori lui $s 1, $s 2, 10 $s 1, $s 2, 10 $s 1, 10 Meaning $s 1 = $s 2 + 10 $s 1 = $s 2 & 10 $s 1 = $s 2 | 10 $s 1 = $s 2 ^ 10 $s 1 = 10 << 16 I-Type Format op = 0 x 8 op = 0 x 9 op = 0 xc op = 0 xd op = 0 xe op = 0 xf rs = $s 2 rs = $s 2 0 rt = $s 1 rt = $s 1 imm 16 = 10 imm 16 = 10 v addi: overflow causes an arithmetic exception ² In case of overflow, result is not written to destination register v addiu: same operation as addi but overflow is ignored v Immediate constant for addi and addiu is signed ² No need for subiu instructions v Immediate constant for andi, ori, xori is unsigned Instruction Set Architecture COE 301 – Computer Organization – KFUPM © Muhamed Mudawar slide 23

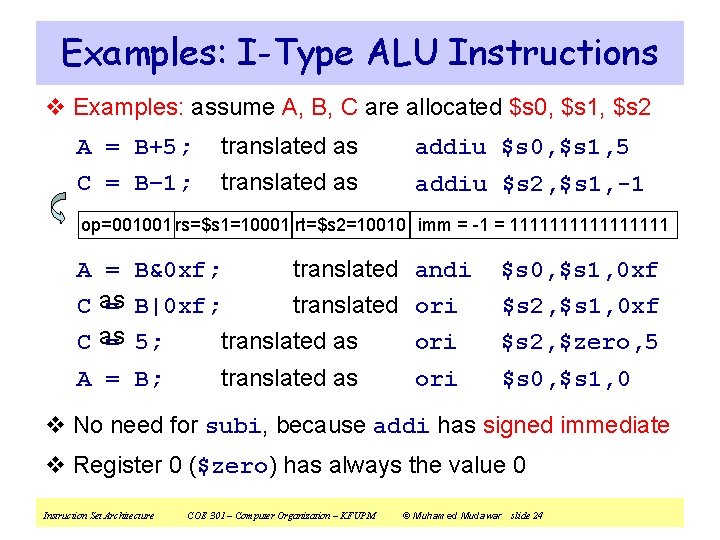

Examples: I-Type ALU Instructions v Examples: assume A, B, C are allocated $s 0, $s 1, $s 2 A = B+5; translated as addiu $s 0, $s 1, 5 C = B– 1; translated as addiu $s 2, $s 1, -1 op=001001 rs=$s 1=10001 rt=$s 2=10010 imm = -1 = 11111111 A = B&0 xf; translated andi C as = B|0 xf; translated ori C as = 5; translated as ori A = B; translated as ori $s 0, $s 1, 0 xf $s 2, $zero, 5 $s 0, $s 1, 0 v No need for subi, because addi has signed immediate v Register 0 ($zero) has always the value 0 Instruction Set Architecture COE 301 – Computer Organization – KFUPM © Muhamed Mudawar slide 24

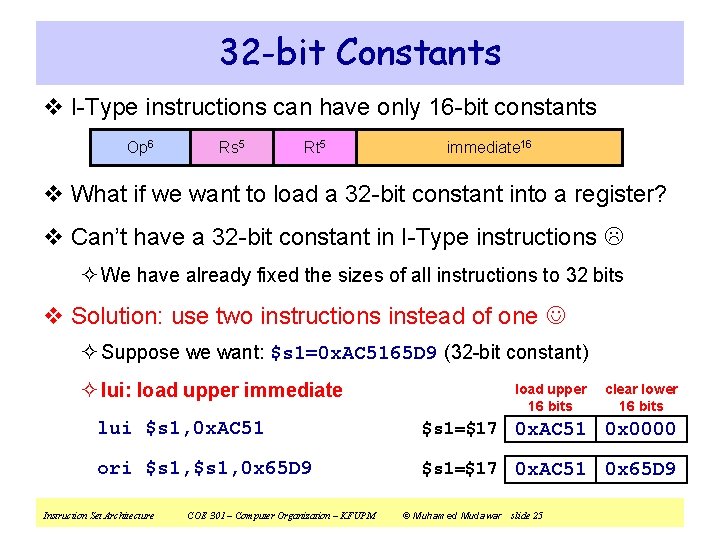

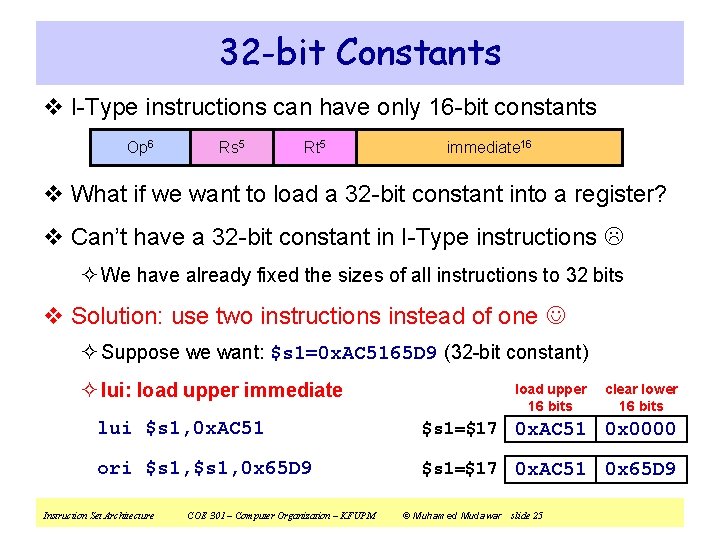

32 -bit Constants v I-Type instructions can have only 16 -bit constants Op 6 Rs 5 Rt 5 immediate 16 v What if we want to load a 32 -bit constant into a register? v Can’t have a 32 -bit constant in I-Type instructions ² We have already fixed the sizes of all instructions to 32 bits v Solution: use two instructions instead of one ² Suppose we want: $s 1=0 x. AC 5165 D 9 (32 -bit constant) ² lui: load upper immediate load upper 16 bits clear lower 16 bits lui $s 1, 0 x. AC 51 $s 1=$17 0 x. AC 51 0 x 0000 ori $s 1, 0 x 65 D 9 $s 1=$17 0 x. AC 51 0 x 65 D 9 Instruction Set Architecture COE 301 – Computer Organization – KFUPM © Muhamed Mudawar slide 25

Next. . . v Instruction Set Architecture v Overview of the MIPS Processor v R-Type Arithmetic, Logical, and Shift Instructions v I-Type Format and Immediate Constants v Jump and Branch Instructions v Translating If Statements and Boolean Expressions v Load and Store Instructions v Translating Loops and Traversing Arrays v Addressing Modes Instruction Set Architecture COE 301 – Computer Organization – KFUPM © Muhamed Mudawar slide 26

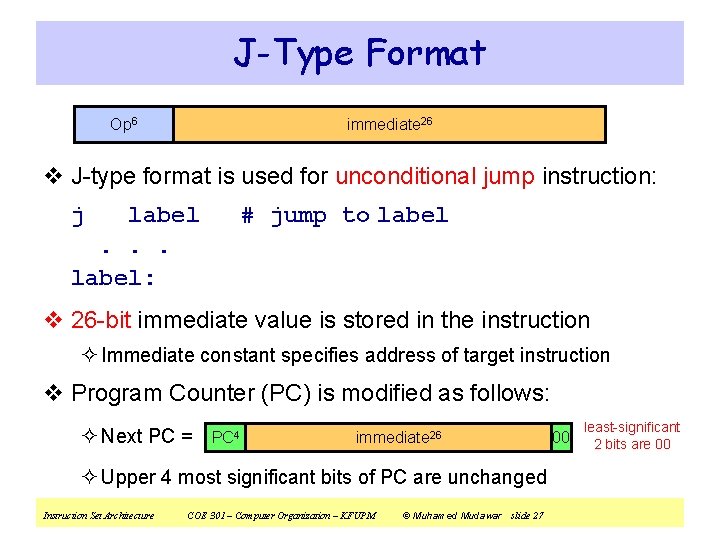

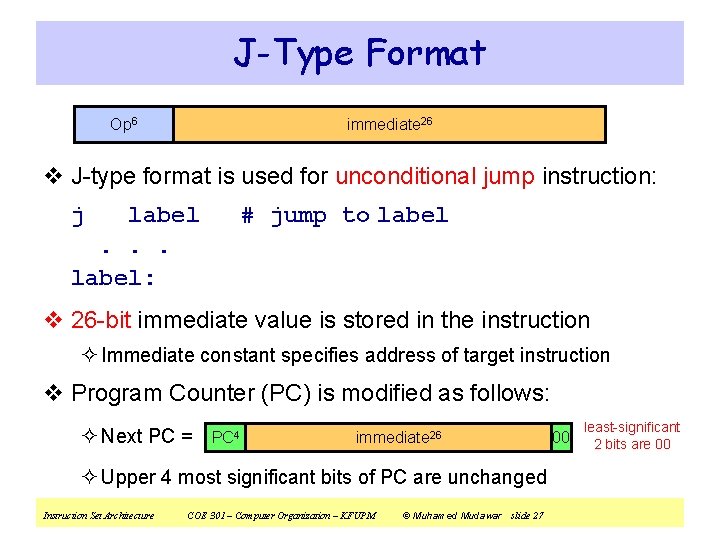

J-Type Format Op 6 immediate 26 v J-type format is used for unconditional jump instruction: j label. . . label: # jump to label v 26 -bit immediate value is stored in the instruction ² Immediate constant specifies address of target instruction v Program Counter (PC) is modified as follows: ² Next PC = PC 4 immediate 26 ² Upper 4 most significant bits of PC are unchanged Instruction Set Architecture COE 301 – Computer Organization – KFUPM © Muhamed Mudawar slide 27 00 least-significant 2 bits are 00

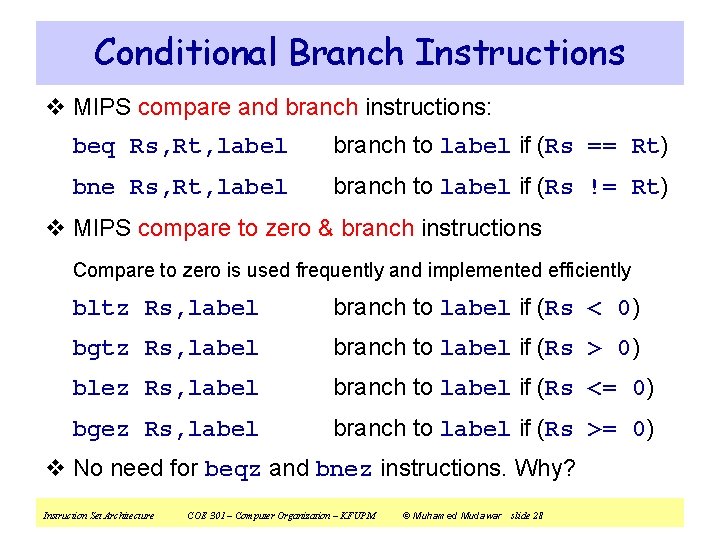

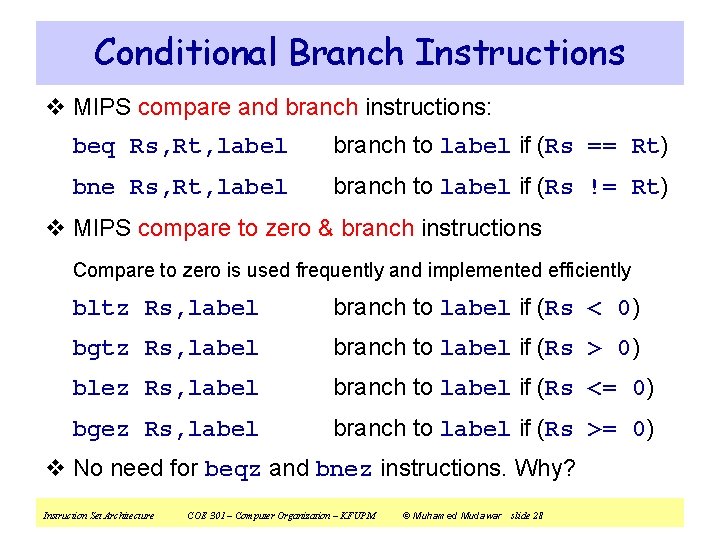

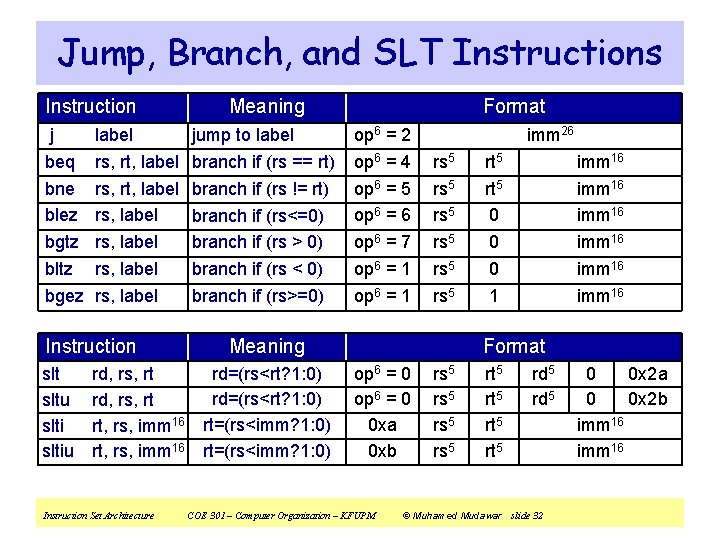

Conditional Branch Instructions v MIPS compare and branch instructions: beq Rs, Rt, label branch to label if (Rs == Rt) bne Rs, Rt, label branch to label if (Rs != Rt) v MIPS compare to zero & branch instructions Compare to zero is used frequently and implemented efficiently bltz Rs, label branch to label if (Rs < 0) bgtz Rs, label branch to label if (Rs > 0) blez Rs, label branch to label if (Rs <= 0) bgez Rs, label branch to label if (Rs >= 0) v No need for beqz and bnez instructions. Why? Instruction Set Architecture COE 301 – Computer Organization – KFUPM © Muhamed Mudawar slide 28

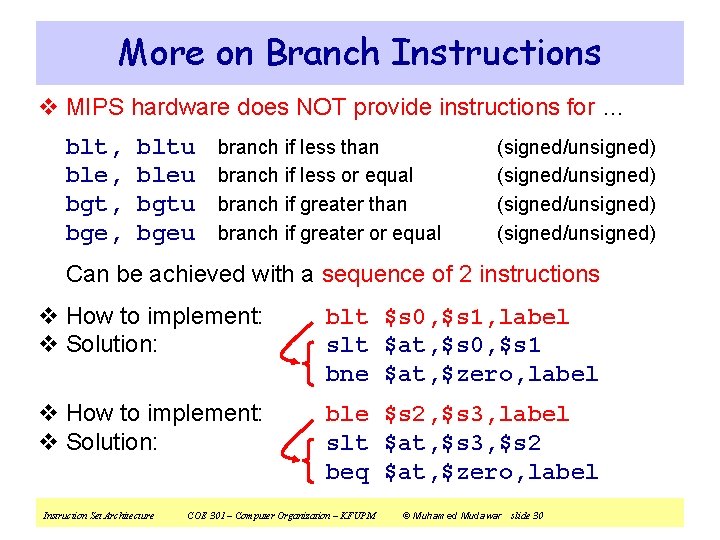

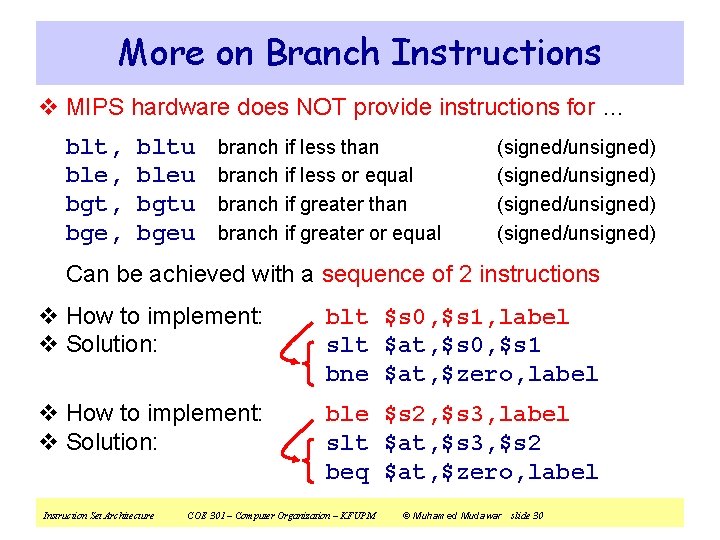

Set on Less Than Instructions v MIPS also provides set on less than instructions slt rd, rs, rt if (rs < rt) rd = 1 else rd = 0 sltu rd, rs, rt unsigned < slti rt, rs, im 16 if (rs < im 16) rt = 1 else rt = 0 sltiu rt, rs, im 16 unsigned < v Signed / Unsigned Comparisons Can produce different results Assume $s 0 = 1 and $s 1 = -1 = 0 xffff $t 0, $s 1 results in $t 0 = 0 sltu $t 0, $s 1 results in $t 0 = 1 slt Instruction Set Architecture COE 301 – Computer Organization – KFUPM © Muhamed Mudawar slide 29

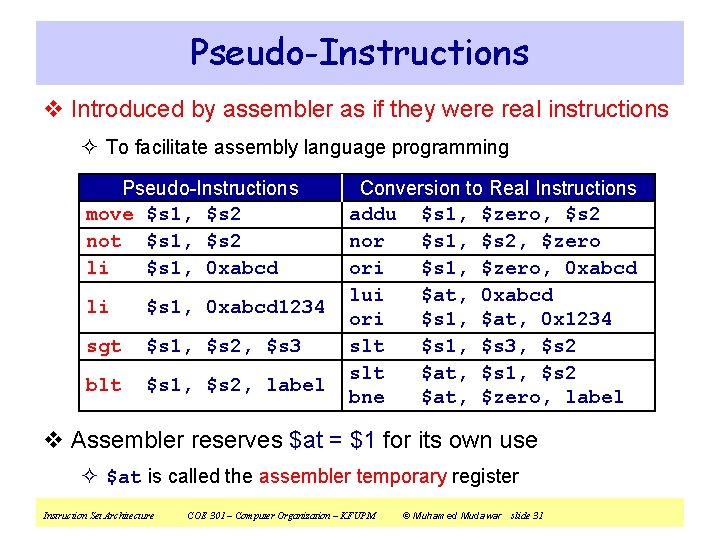

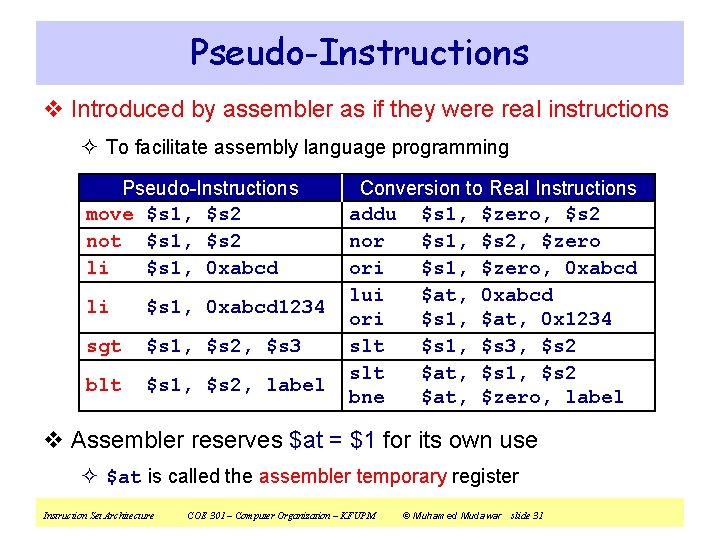

More on Branch Instructions v MIPS hardware does NOT provide instructions for … blt, ble, bgt, bge, bltu bleu bgtu bgeu branch if less than branch if less or equal branch if greater than branch if greater or equal (signed/unsigned) Can be achieved with a sequence of 2 instructions v How to implement: v Solution: blt $s 0, $s 1, label slt $at, $s 0, $s 1 bne $at, $zero, label v How to implement: v Solution: ble $s 2, $s 3, label slt $at, $s 3, $s 2 beq $at, $zero, label Instruction Set Architecture COE 301 – Computer Organization – KFUPM © Muhamed Mudawar slide 30

Pseudo-Instructions v Introduced by assembler as if they were real instructions ² To facilitate assembly language programming Pseudo-Instructions move $s 1, $s 2 not $s 1, $s 2 li $s 1, 0 xabcd 1234 sgt $s 1, $s 2, $s 3 blt $s 1, $s 2, label Conversion to Real Instructions addu $s 1, $zero, $s 2 nor $s 1, $s 2, $zero ori $s 1, $zero, 0 xabcd lui $at, 0 xabcd ori $s 1, $at, 0 x 1234 slt $s 1, $s 3, $s 2 slt $at, $s 1, $s 2 bne $at, $zero, label v Assembler reserves $at = $1 for its own use ² $at is called the assembler temporary register Instruction Set Architecture COE 301 – Computer Organization – KFUPM © Muhamed Mudawar slide 31

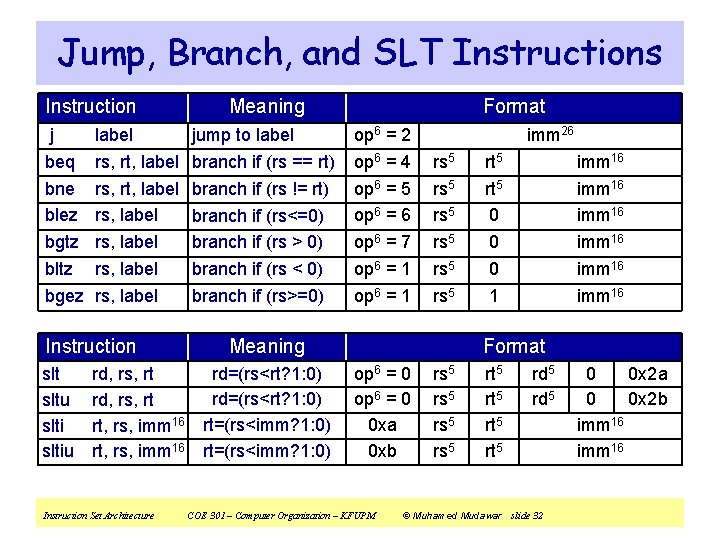

Jump, Branch, and SLT Instructions Instruction j beq bne blez bgtz bltz bgez label rs, rt, label rs, label Instruction sltu sltiu rd, rs, rt rt, rs, imm 16 Instruction Set Architecture Meaning jump to label branch if (rs == rt) branch if (rs != rt) branch if (rs<=0) branch if (rs > 0) branch if (rs < 0) branch if (rs>=0) Format op 6 = 2 op 6 = 4 op 6 = 5 op 6 = 6 op 6 = 7 op 6 = 1 imm 26 rs 5 rs 5 Meaning rd=(rs<rt? 1: 0) rt=(rs<imm? 1: 0) rt 5 0 0 0 1 imm 16 imm 16 Format op 6 = 0 0 xa 0 xb COE 301 – Computer Organization – KFUPM rs 5 rt 5 rd 5 © Muhamed Mudawar slide 32 0 0 x 2 a 0 0 x 2 b imm 16

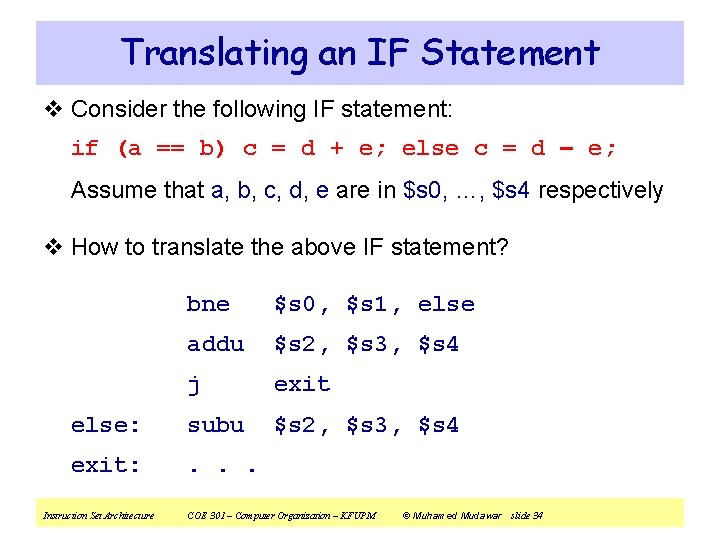

Next. . . v Instruction Set Architecture v Overview of the MIPS Processor v R-Type Arithmetic, Logical, and Shift Instructions v I-Type Format and Immediate Constants v Jump and Branch Instructions v Translating If Statements and Boolean Expressions v Load and Store Instructions v Translating Loops and Traversing Arrays v Addressing Modes Instruction Set Architecture COE 301 – Computer Organization – KFUPM © Muhamed Mudawar slide 33

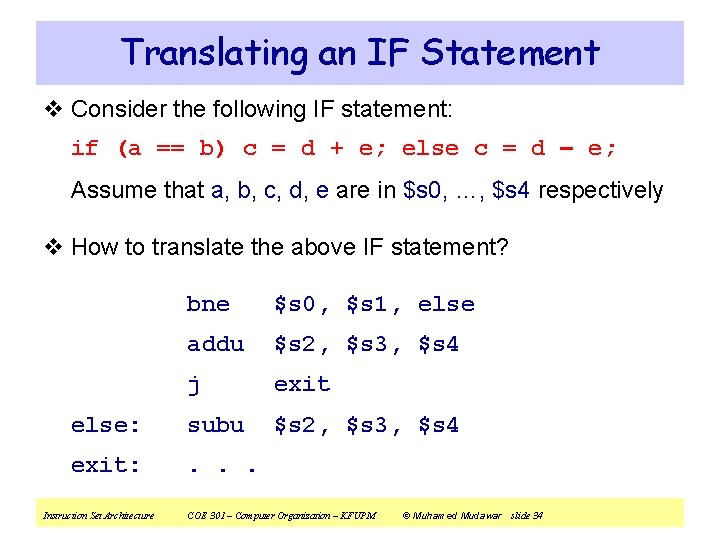

Translating an IF Statement v Consider the following IF statement: if (a == b) c = d + e; else c = d – e; Assume that a, b, c, d, e are in $s 0, …, $s 4 respectively v How to translate the above IF statement? bne $s 0, $s 1, else addu $s 2, $s 3, $s 4 j exit else: subu $s 2, $s 3, $s 4 exit: . . . Instruction Set Architecture COE 301 – Computer Organization – KFUPM © Muhamed Mudawar slide 34

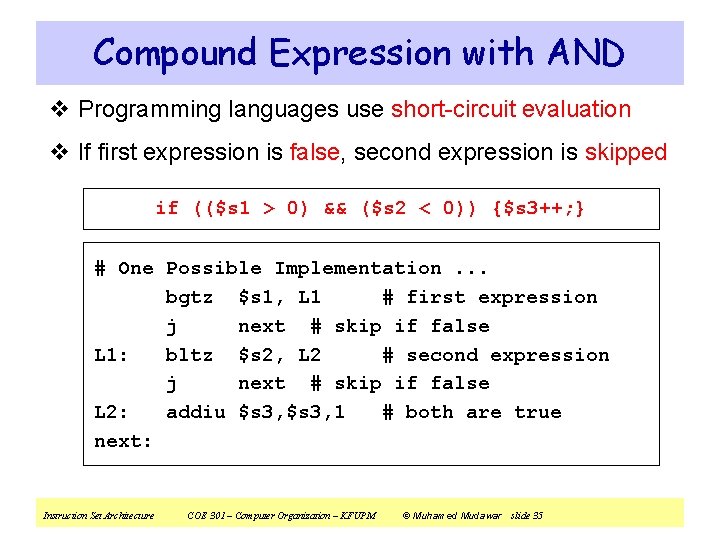

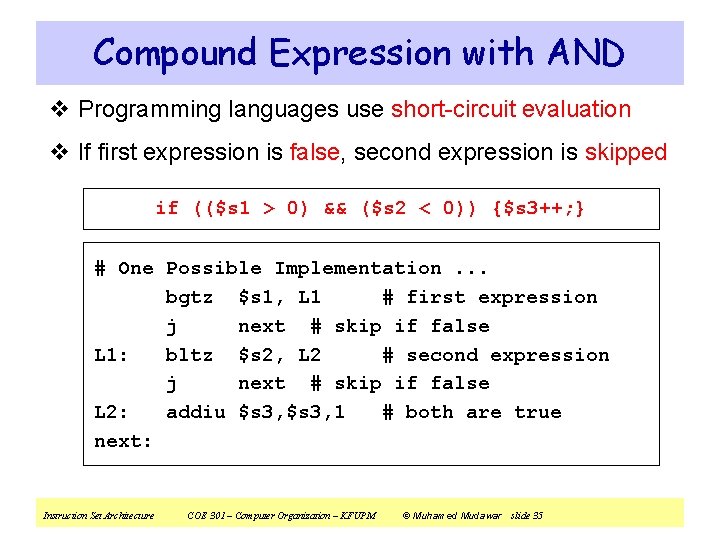

Compound Expression with AND v Programming languages use short-circuit evaluation v If first expression is false, second expression is skipped if (($s 1 > 0) && ($s 2 < 0)) {$s 3++; } # One Possible Implementation. . . bgtz $s 1, L 1 # first expression j next # skip if false L 1: bltz $s 2, L 2 # second expression j next # skip if false L 2: addiu $s 3, 1 # both are true next: Instruction Set Architecture COE 301 – Computer Organization – KFUPM © Muhamed Mudawar slide 35

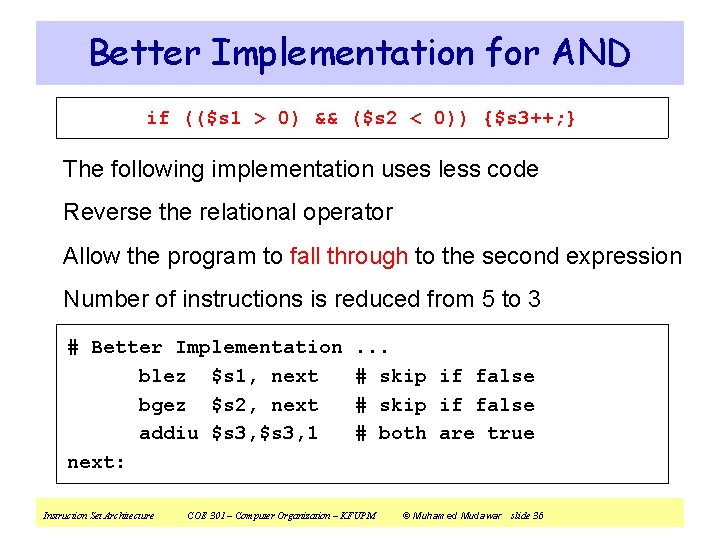

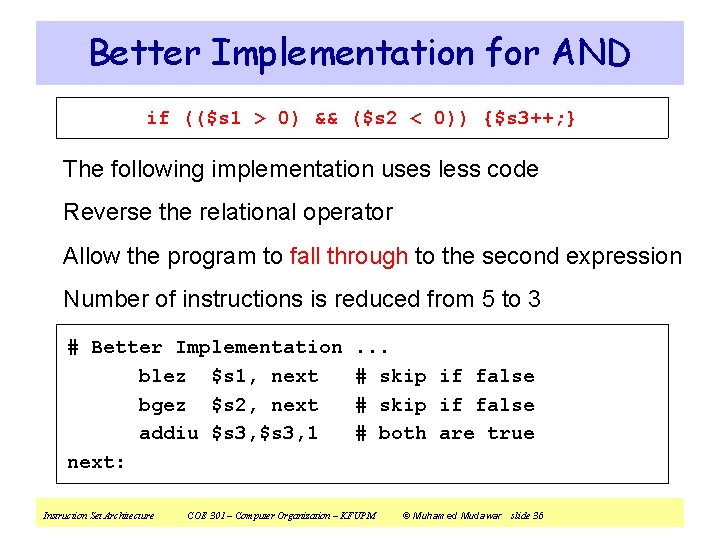

Better Implementation for AND if (($s 1 > 0) && ($s 2 < 0)) {$s 3++; } The following implementation uses less code Reverse the relational operator Allow the program to fall through to the second expression Number of instructions is reduced from 5 to 3 # Better Implementation blez $s 1, next bgez $s 2, next addiu $s 3, 1 next: Instruction Set Architecture . . . # skip if false # both are true COE 301 – Computer Organization – KFUPM © Muhamed Mudawar slide 36

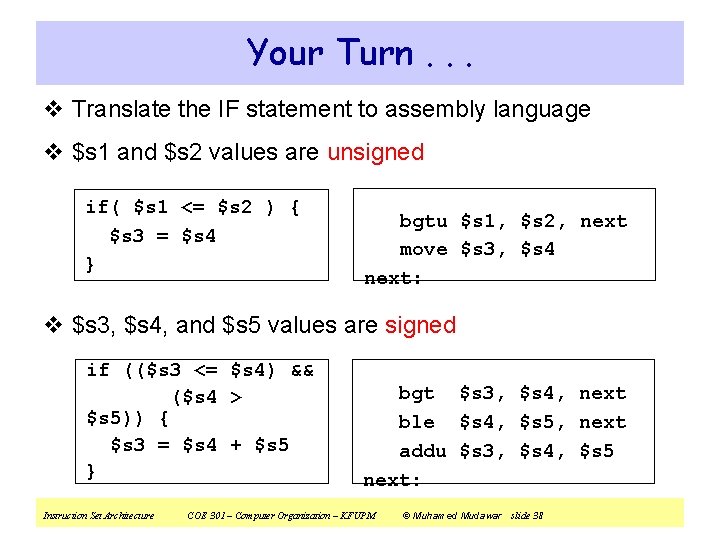

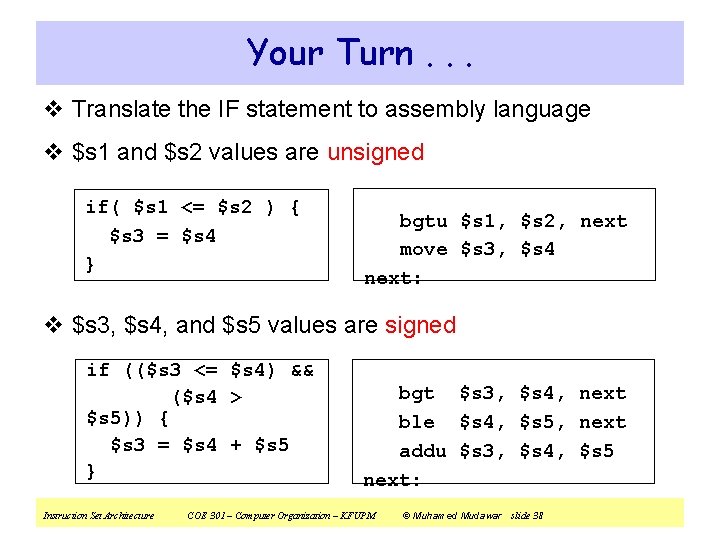

Compound Expression with OR v Short-circuit evaluation for logical OR v If first expression is true, second expression is skipped if (($sl > $s 2) || ($s 2 > $s 3)) {$s 4 = 1; } v Use fall-through to keep the code as short as possible bgt $s 1, $s 2, L 1 # yes, execute if part ble $s 2, $s 3, next # no: skip if part L 1: li next: $s 4, 1 # set $s 4 to 1 v bgt, ble, and li are pseudo-instructions ² Translated by the assembler to real instructions Instruction Set Architecture COE 301 – Computer Organization – KFUPM © Muhamed Mudawar slide 37

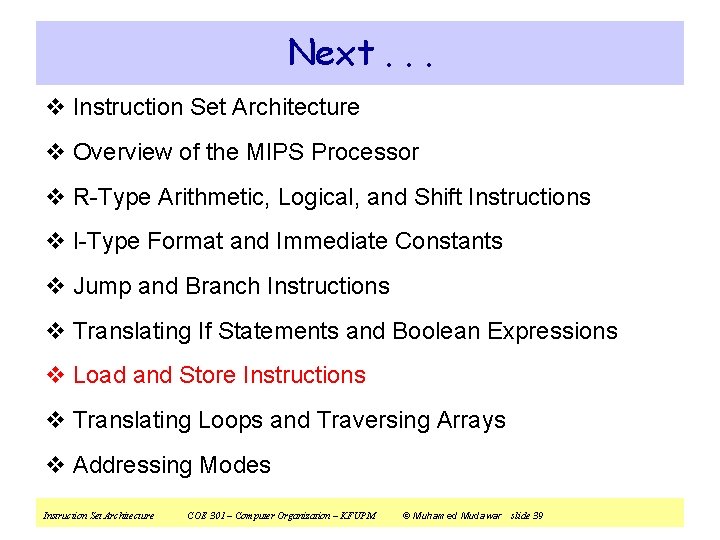

Your Turn. . . v Translate the IF statement to assembly language v $s 1 and $s 2 values are unsigned if( $s 1 <= $s 2 ) { $s 3 = $s 4 } bgtu $s 1, $s 2, next move $s 3, $s 4 next: v $s 3, $s 4, and $s 5 values are signed if (($s 3 <= $s 4) && ($s 4 > $s 5)) { $s 3 = $s 4 + $s 5 } Instruction Set Architecture bgt $s 3, $s 4, next ble $s 4, $s 5, next addu $s 3, $s 4, $s 5 next: COE 301 – Computer Organization – KFUPM © Muhamed Mudawar slide 38

Next. . . v Instruction Set Architecture v Overview of the MIPS Processor v R-Type Arithmetic, Logical, and Shift Instructions v I-Type Format and Immediate Constants v Jump and Branch Instructions v Translating If Statements and Boolean Expressions v Load and Store Instructions v Translating Loops and Traversing Arrays v Addressing Modes Instruction Set Architecture COE 301 – Computer Organization – KFUPM © Muhamed Mudawar slide 39

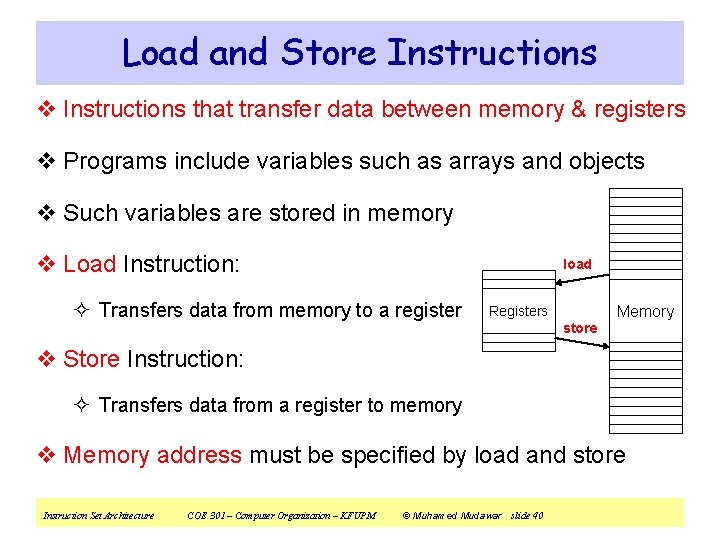

Load and Store Instructions v Instructions that transfer data between memory & registers v Programs include variables such as arrays and objects v Such variables are stored in memory v Load Instruction: load ² Transfers data from memory to a register Registers store Memory v Store Instruction: ² Transfers data from a register to memory v Memory address must be specified by load and store Instruction Set Architecture COE 301 – Computer Organization – KFUPM © Muhamed Mudawar slide 40

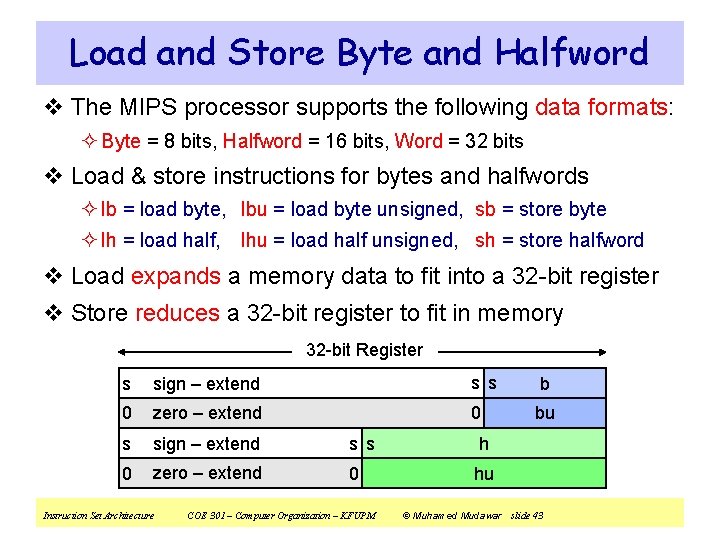

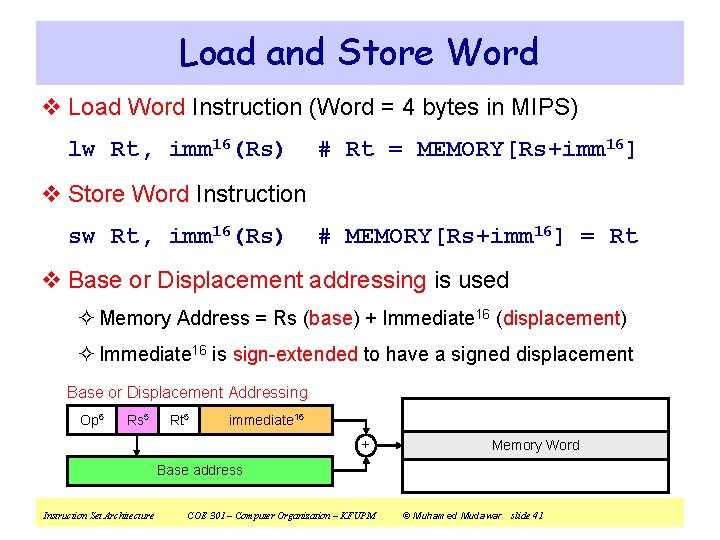

Load and Store Word v Load Word Instruction (Word = 4 bytes in MIPS) lw Rt, imm 16(Rs) # Rt = MEMORY[Rs+imm 16] v Store Word Instruction sw Rt, imm 16(Rs) # MEMORY[Rs+imm 16] = Rt v Base or Displacement addressing is used ² Memory Address = Rs (base) + Immediate 16 (displacement) ² Immediate 16 is sign-extended to have a signed displacement Base or Displacement Addressing Op 6 Rs 5 Rt 5 immediate 16 + Memory Word Base address Instruction Set Architecture COE 301 – Computer Organization – KFUPM © Muhamed Mudawar slide 41

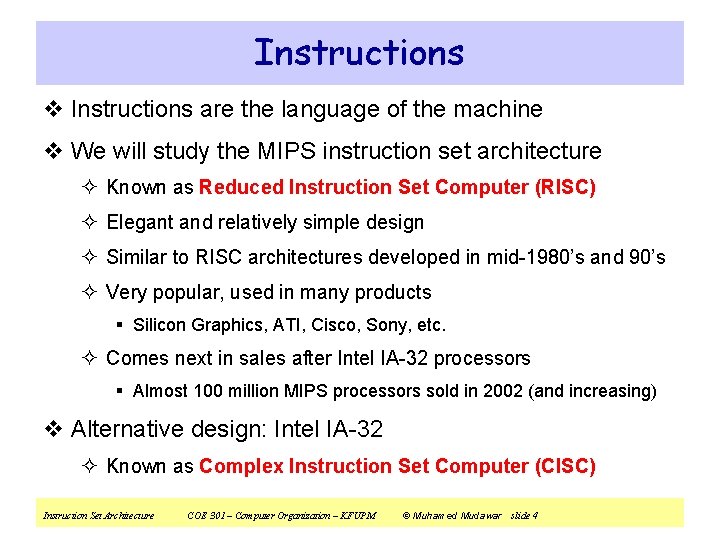

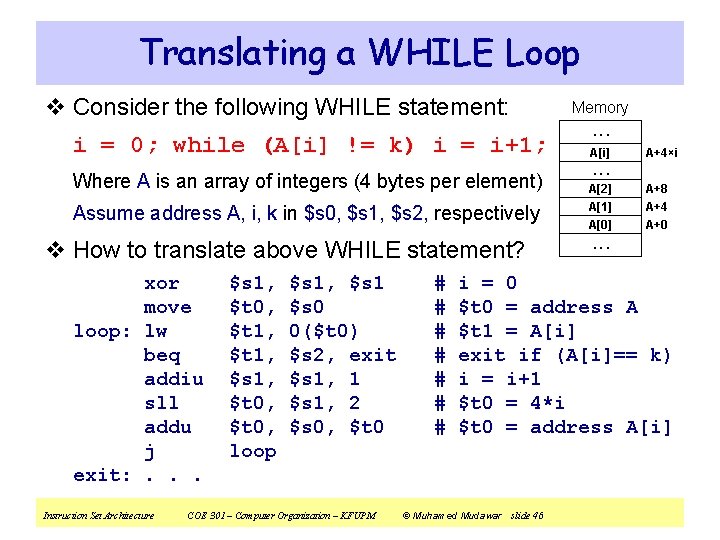

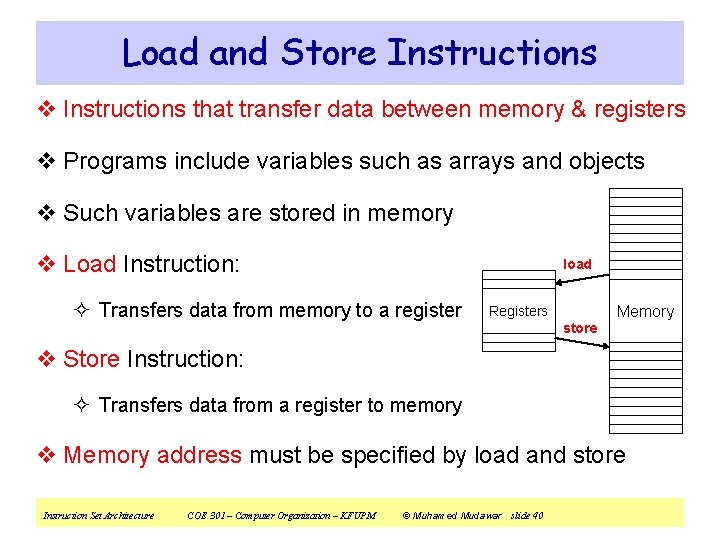

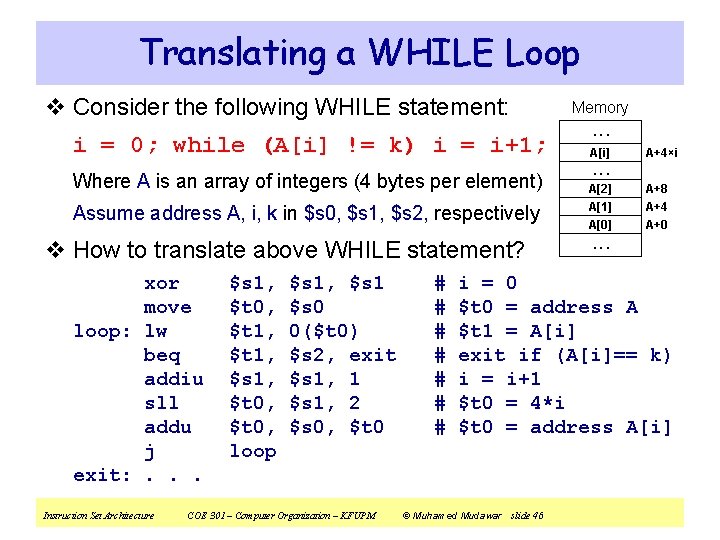

![Example on Load Store v Translate A1 A2 5 A is Example on Load & Store v Translate A[1] = A[2] + 5 (A is](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/1df6014b6311ca484813b73f9cafe9a4/image-42.jpg)

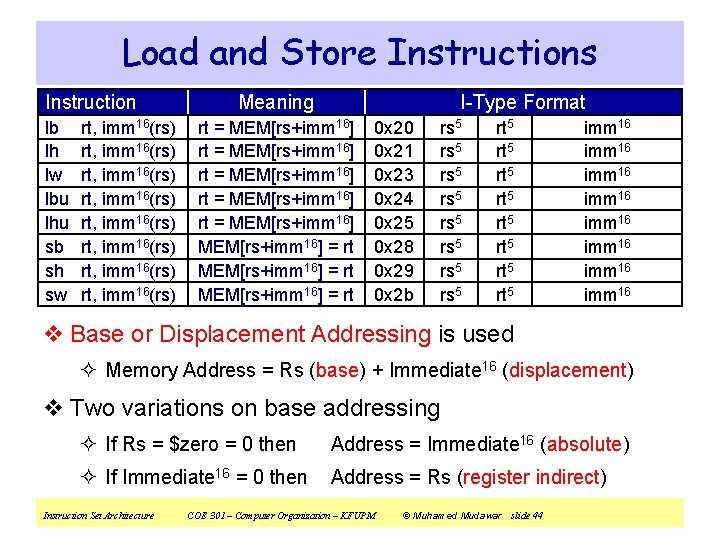

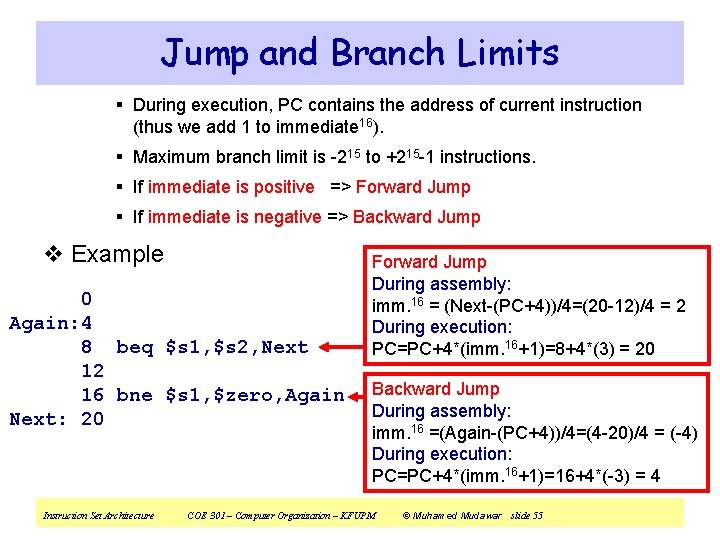

Example on Load & Store v Translate A[1] = A[2] + 5 (A is an array of words) ² Assume that address of array A is stored in register $s 0 lw $s 1, 8($s 0) # $s 1 = A[2] addiu $s 2, $s 1, 5 # $s 2 = A[2] + 5 sw $s 2, 4($s 0) # A[1] = $s 2 v Index of A[2] and A[1] should be multiplied by 4. Why? Memory Registers . . . $s 0 = $16 address of A $s 1 = $17 value of A[2] $s 2 = $18 A[2] + 5. . . lw sw A[3] A[2] A[1] A[0] A+12 A+8 A+4 A+0 . . . Instruction Set Architecture COE 301 – Computer Organization – KFUPM © Muhamed Mudawar slide 42

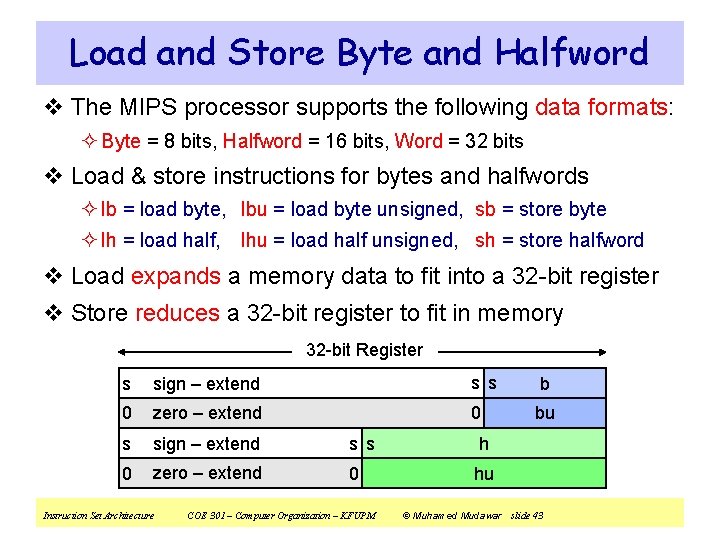

Load and Store Byte and Halfword v The MIPS processor supports the following data formats: ² Byte = 8 bits, Halfword = 16 bits, Word = 32 bits v Load & store instructions for bytes and halfwords ² lb = load byte, lbu = load byte unsigned, sb = store byte ² lh = load half, lhu = load half unsigned, sh = store halfword v Load expands a memory data to fit into a 32 -bit register v Store reduces a 32 -bit register to fit in memory 32 -bit Register s sign – extend s s b 0 zero – extend 0 bu s sign – extend s s h 0 zero – extend 0 hu Instruction Set Architecture COE 301 – Computer Organization – KFUPM © Muhamed Mudawar slide 43

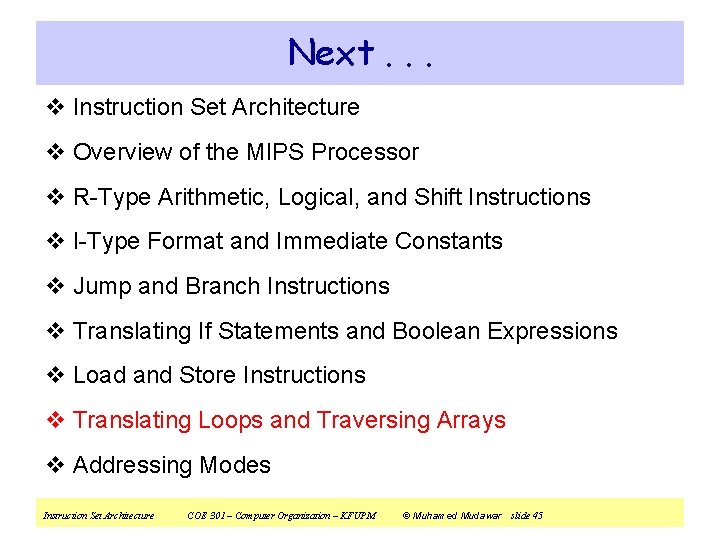

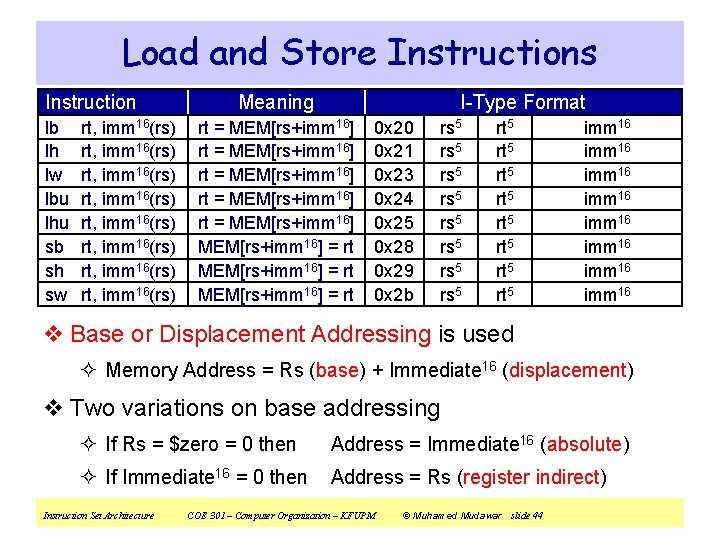

Load and Store Instructions Instruction lb lh lw lbu lhu sb sh sw rt, imm 16(rs) rt, imm 16(rs) Meaning I-Type Format rt = MEM[rs+imm 16] rt = MEM[rs+imm 16] = rt 0 x 20 0 x 21 0 x 23 0 x 24 0 x 25 0 x 28 0 x 29 0 x 2 b rs 5 rs 5 rt 5 rt 5 imm 16 imm 16 v Base or Displacement Addressing is used ² Memory Address = Rs (base) + Immediate 16 (displacement) v Two variations on base addressing ² If Rs = $zero = 0 then Address = Immediate 16 (absolute) ² If Immediate 16 = 0 then Address = Rs (register indirect) Instruction Set Architecture COE 301 – Computer Organization – KFUPM © Muhamed Mudawar slide 44

Next. . . v Instruction Set Architecture v Overview of the MIPS Processor v R-Type Arithmetic, Logical, and Shift Instructions v I-Type Format and Immediate Constants v Jump and Branch Instructions v Translating If Statements and Boolean Expressions v Load and Store Instructions v Translating Loops and Traversing Arrays v Addressing Modes Instruction Set Architecture COE 301 – Computer Organization – KFUPM © Muhamed Mudawar slide 45

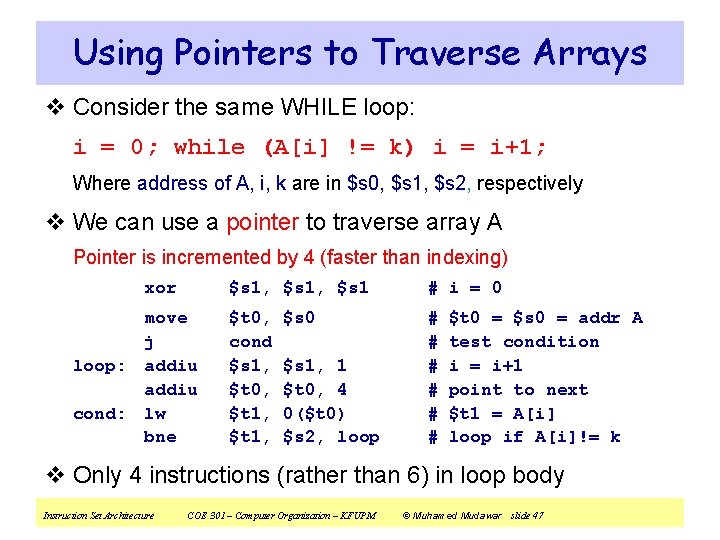

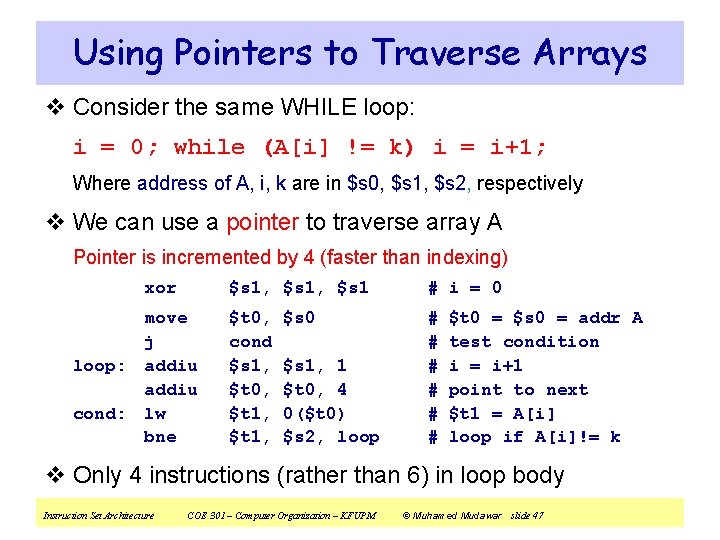

Translating a WHILE Loop v Consider the following WHILE statement: i = 0; while (A[i] != k) i = i+1; Where A is an array of integers (4 bytes per element) Assume address A, i, k in $s 0, $s 1, $s 2, respectively v How to translate above WHILE statement? xor move loop: lw beq addiu sll addu j exit: . . . Instruction Set Architecture $s 1, $t 0, $t 1, $s 1, $t 0, loop $s 1, $s 1 $s 0 0($t 0) $s 2, exit $s 1, 1 $s 1, 2 $s 0, $t 0 COE 301 – Computer Organization – KFUPM # # # # Memory. . . A[i] A+4×i . . . A[2] A+8 A[1] A+4 A[0] A+0 . . . i = 0 $t 0 = address A $t 1 = A[i] exit if (A[i]== k) i = i+1 $t 0 = 4*i $t 0 = address A[i] © Muhamed Mudawar slide 46

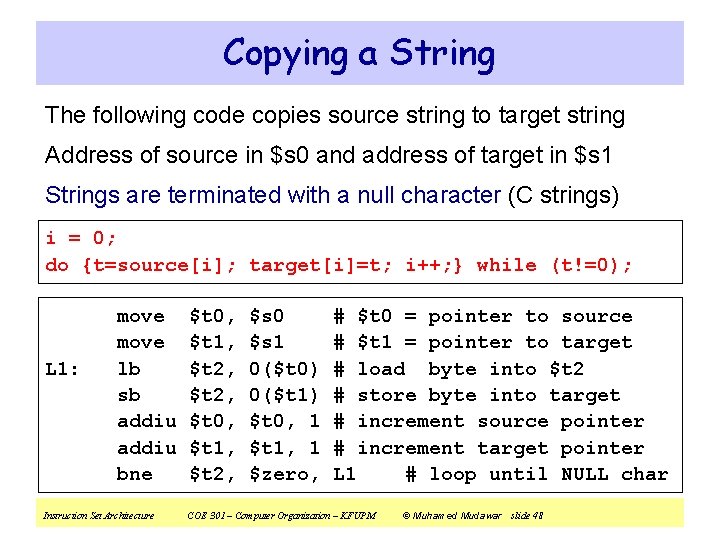

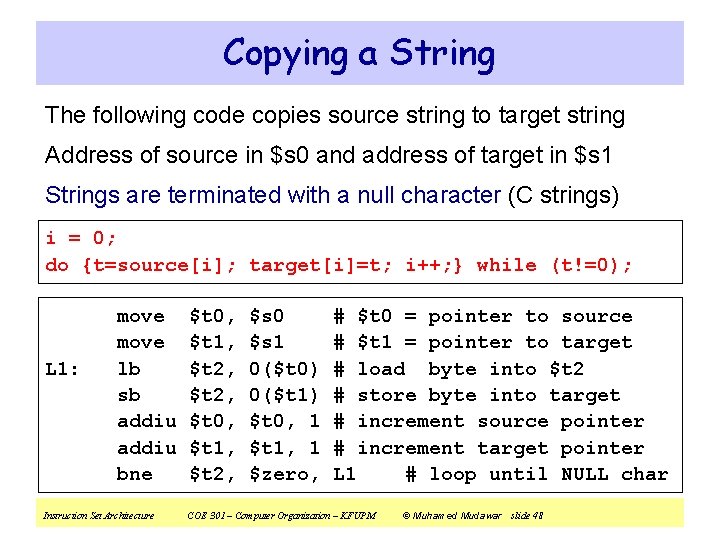

Using Pointers to Traverse Arrays v Consider the same WHILE loop: i = 0; while (A[i] != k) i = i+1; Where address of A, i, k are in $s 0, $s 1, $s 2, respectively v We can use a pointer to traverse array A Pointer is incremented by 4 (faster than indexing) xor move j loop: addiu cond: lw bne $s 1, $s 1 # i = 0 $t 0, cond $s 1, $t 0, $t 1, # # # $s 0 $s 1, 1 $t 0, 4 0($t 0) $s 2, loop $t 0 = $s 0 = addr A test condition i = i+1 point to next $t 1 = A[i] loop if A[i]!= k v Only 4 instructions (rather than 6) in loop body Instruction Set Architecture COE 301 – Computer Organization – KFUPM © Muhamed Mudawar slide 47

Copying a String The following code copies source string to target string Address of source in $s 0 and address of target in $s 1 Strings are terminated with a null character (C strings) i = 0; do {t=source[i]; target[i]=t; i++; } while (t!=0); L 1: move lb sb addiu bne Instruction Set Architecture $t 0, $t 1, $t 2, $s 0 $s 1 0($t 0) 0($t 1) $t 0, 1 $t 1, 1 $zero, # $t 0 = pointer to source # $t 1 = pointer to target # load byte into $t 2 # store byte into target # increment source pointer # increment target pointer L 1 # loop until NULL char COE 301 – Computer Organization – KFUPM © Muhamed Mudawar slide 48

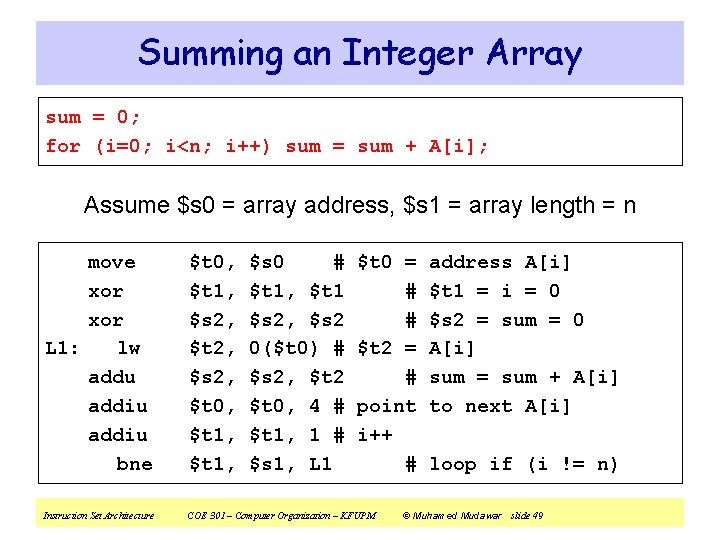

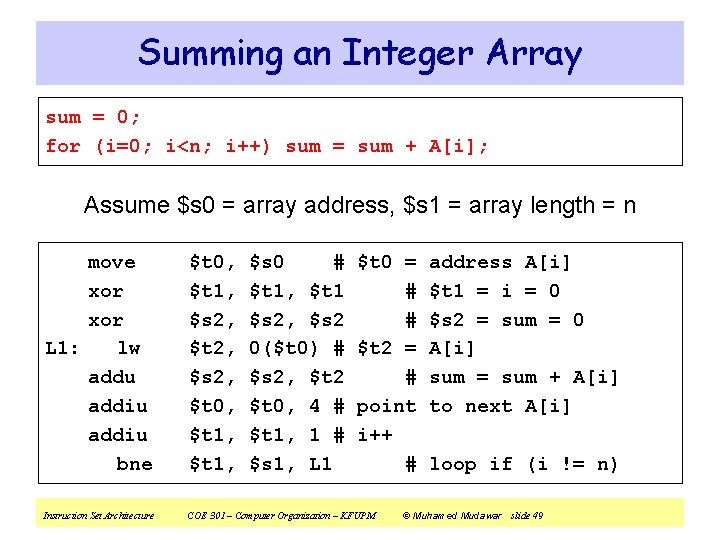

Summing an Integer Array sum = 0; for (i=0; i<n; i++) sum = sum + A[i]; Assume $s 0 = array address, $s 1 = array length = n move xor L 1: lw addu addiu bne $t 0, $t 1, $s 2, $t 2, $s 2, $t 0, $t 1, $s 0 # $t 1, $t 1 $s 2, $s 2 0($t 0) # $s 2, $t 2 $t 0, 4 # $t 1, 1 # $s 1, L 1 $t 0 = # # $t 2 = # point i++ # Instruction Set Architecture COE 301 – Computer Organization – KFUPM address A[i] $t 1 = i = 0 $s 2 = sum = 0 A[i] sum = sum + A[i] to next A[i] loop if (i != n) © Muhamed Mudawar slide 49

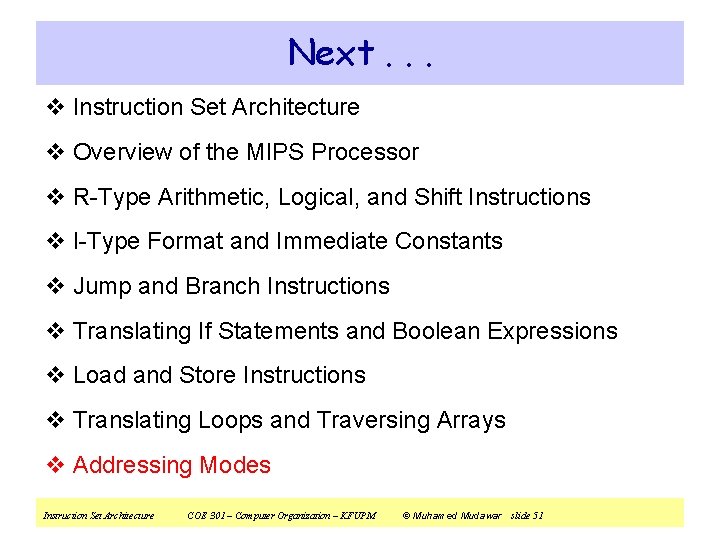

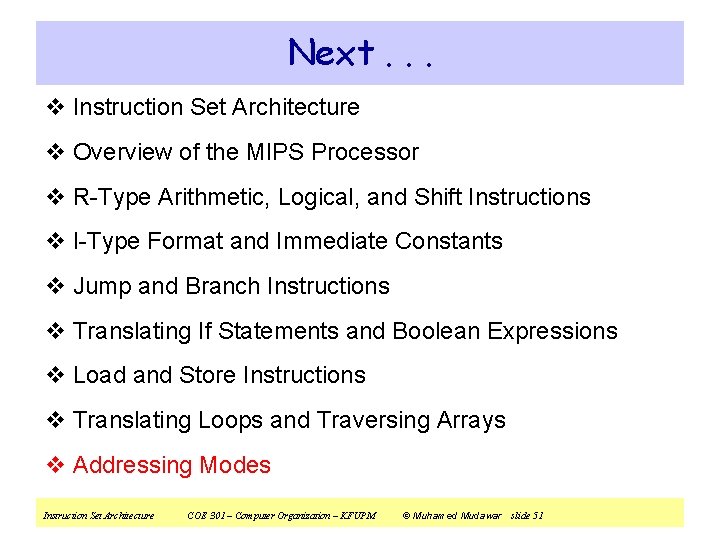

Element Addresses in a 2 D Array v 2 D array elements are usually stored in memory in a row wise fashion v Address calculation is essential when programming in assembly COLS 0 1 … j … COLS-1 ROWS 0 1 … i … ROWS-1 &matrix[i][j] = &matrix + (i×COLS + j) × Element_size Instruction Set Architecture COE 301 – Computer Organization – KFUPM © Muhamed Mudawar slide 50

Next. . . v Instruction Set Architecture v Overview of the MIPS Processor v R-Type Arithmetic, Logical, and Shift Instructions v I-Type Format and Immediate Constants v Jump and Branch Instructions v Translating If Statements and Boolean Expressions v Load and Store Instructions v Translating Loops and Traversing Arrays v Addressing Modes Instruction Set Architecture COE 301 – Computer Organization – KFUPM © Muhamed Mudawar slide 51

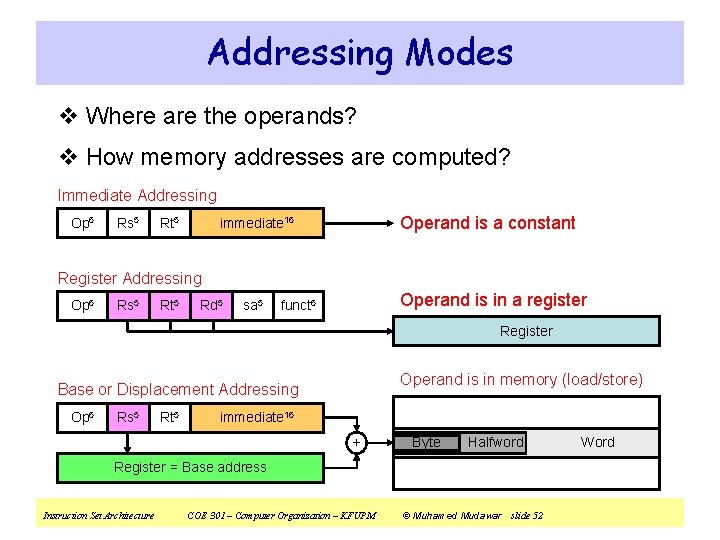

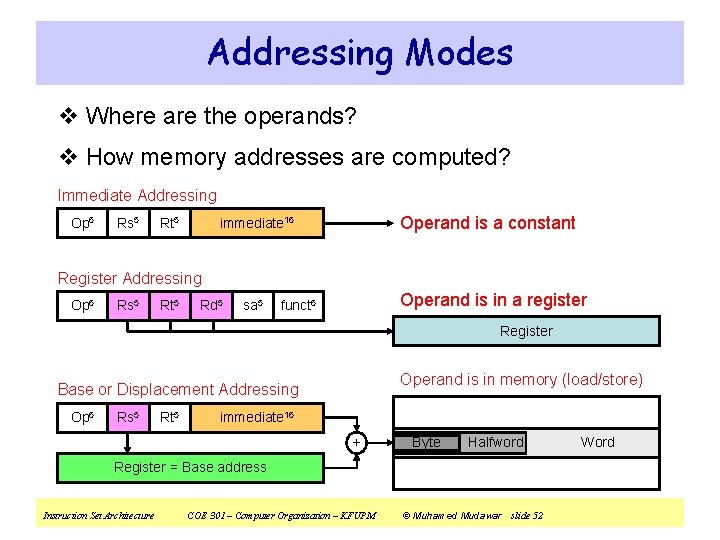

Addressing Modes v Where are the operands? v How memory addresses are computed? Immediate Addressing Op 6 Rs 5 Rt 5 Operand is a constant immediate 16 Register Addressing Op 6 Rs 5 Rt 5 Rd 5 sa 5 Operand is in a register funct 6 Register Operand is in memory (load/store) Base or Displacement Addressing Op 6 Rs 5 Rt 5 immediate 16 + Byte Halfword Register = Base address Instruction Set Architecture COE 301 – Computer Organization – KFUPM © Muhamed Mudawar slide 52 Word

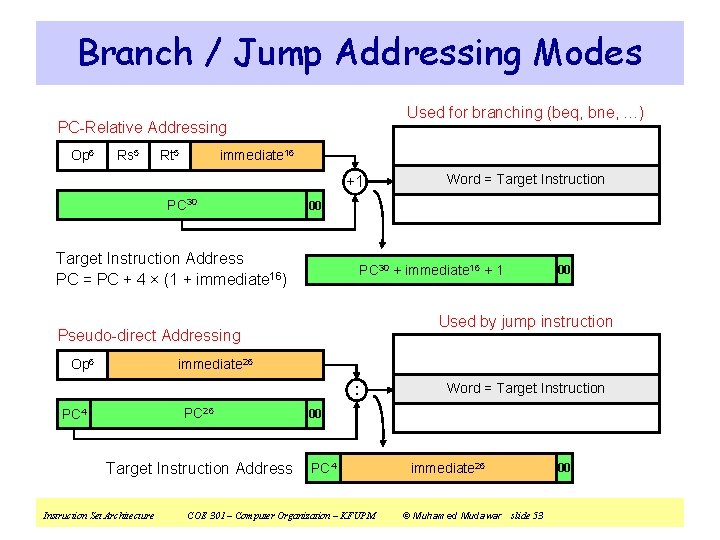

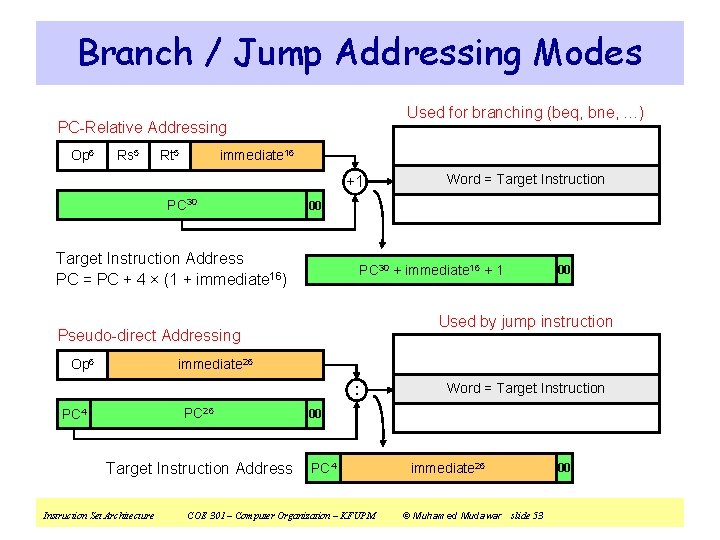

Branch / Jump Addressing Modes Used for branching (beq, bne, …) PC-Relative Addressing Op 6 Rs 5 Rt 5 immediate 16 +1 PC 30 00 Target Instruction Address PC = PC + 4 × (1 + immediate 16) PC 30 + immediate 16 + 1 00 Used by jump instruction Pseudo-direct Addressing Op 6 Word = Target Instruction immediate 26 : PC 26 PC 4 Target Instruction Address Instruction Set Architecture Word = Target Instruction 00 PC 4 COE 301 – Computer Organization – KFUPM immediate 26 © Muhamed Mudawar slide 53 00

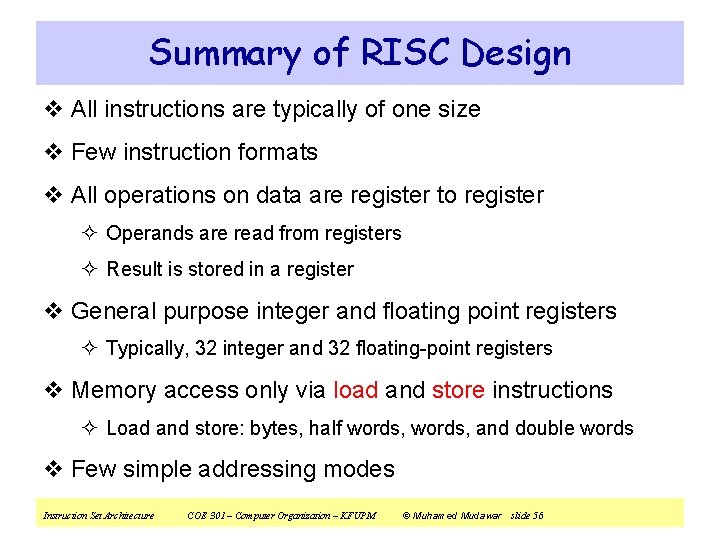

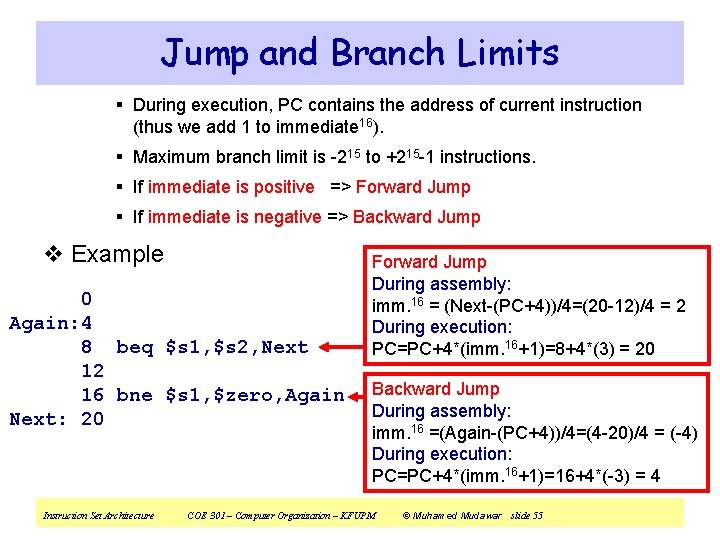

Jump and Branch Limits v Jump Address Boundary = 226 instructions = 256 MB ² Text segment cannot exceed 226 instructions or 256 MB ² Upper 4 bits of PC are unchanged Target Instruction Address PC 4 immediate 26 00 v Branch Address Boundary ² Branch instructions use I-Type format (16 -bit immediate constant) ² PC-relative addressing: PC 30 + immediate 16 + 1 00 § Target instruction address = PC + 4×(1 + immediate 16) § During assembly: immediate=(Target address – (PC+4))/4, where PC contains address of current instruction Instruction Set Architecture COE 301 – Computer Organization – KFUPM © Muhamed Mudawar slide 54

Jump and Branch Limits § During execution, PC contains the address of current instruction (thus we add 1 to immediate 16). § Maximum branch limit is -215 to +215 -1 instructions. § If immediate is positive => Forward Jump § If immediate is negative => Backward Jump v Example 0 Again: 4 8 beq $s 1, $s 2, Next 12 16 bne $s 1, $zero, Again Next: 20 Instruction Set Architecture Forward Jump During assembly: imm. 16 = (Next-(PC+4))/4=(20 -12)/4 = 2 During execution: PC=PC+4*(imm. 16+1)=8+4*(3) = 20 Backward Jump During assembly: imm. 16 =(Again-(PC+4))/4=(4 -20)/4 = (-4) During execution: PC=PC+4*(imm. 16+1)=16+4*(-3) = 4 COE 301 – Computer Organization – KFUPM © Muhamed Mudawar slide 55

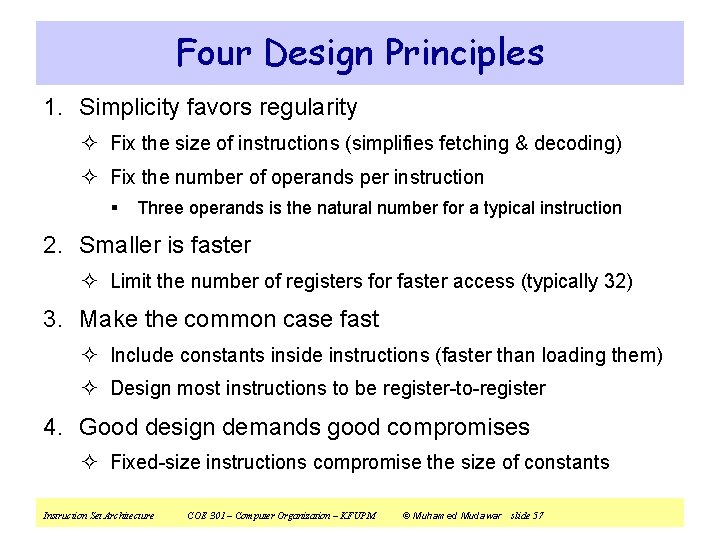

Summary of RISC Design v All instructions are typically of one size v Few instruction formats v All operations on data are register to register ² Operands are read from registers ² Result is stored in a register v General purpose integer and floating point registers ² Typically, 32 integer and 32 floating-point registers v Memory access only via load and store instructions ² Load and store: bytes, half words, and double words v Few simple addressing modes Instruction Set Architecture COE 301 – Computer Organization – KFUPM © Muhamed Mudawar slide 56

Four Design Principles 1. Simplicity favors regularity ² Fix the size of instructions (simplifies fetching & decoding) ² Fix the number of operands per instruction § Three operands is the natural number for a typical instruction 2. Smaller is faster ² Limit the number of registers for faster access (typically 32) 3. Make the common case fast ² Include constants inside instructions (faster than loading them) ² Design most instructions to be register-to-register 4. Good design demands good compromises ² Fixed-size instructions compromise the size of constants Instruction Set Architecture COE 301 – Computer Organization – KFUPM © Muhamed Mudawar slide 57