Inglese 16 17 Lezioni 19 22 Lezioni 19

![• • • his doctrine [di Locke] has some strange consequences that the • • • his doctrine [di Locke] has some strange consequences that the](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h/245dafb78e72efb24bb69007204ccc86/image-7.jpg)

- Slides: 44

Inglese 16 -17 Lezioni 19 -22

• Lezioni 19 -20 • 21 Nov. 2016

Recupero • Vi ricordo la lezione di recupero oggi pomeriggio ore 17

Reid, Essay 3, chapter 6: Of Locke’s account of our personal identity • He [Locke] is absolutely right in his thesis that to know what • is meant by ‘same person’ we must consider what ‘person’ • stands for. He defines ‘person’ as a thinking being endowed • with reason and with consciousness—and he thinks that • consciousness is inseparable from thought. • From this definition it follows that while thinking • being continues to exist, and continues thinking, it must be • the same person.

• To say that • • the thinking being is the person, • and yet that • • the person ceases to exist while thinking being • continues, • or that • • the person continues while thinking being ceases • to exist, • strikes me as a manifest contradiction.

• One would think that the definition of ‘person’ would • completely settle the question of what the nature of personal • identity is, or what personal identity consists in, though • there might still remain a question about how we come to • know and be assured of our personal identity. But Locke • tells us: • SALTIAMO IL BRANO DI LOCKE CITATO DA REID

![his doctrine di Locke has some strange consequences that the • • • his doctrine [di Locke] has some strange consequences that the](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h/245dafb78e72efb24bb69007204ccc86/image-7.jpg)

• • • his doctrine [di Locke] has some strange consequences that the author was aware of. For example: if the same consciousness could be transferred from one thinking being to another (which Locke thinks we can’t show to be impossible), then two or twenty thinking beings could be the same person. And if a thinking being were to lose the consciousness of the actions he had done (which surely is possible), then he is not the person who performed those actions; so that one thinking being could be two or twenty different persons if he lost the consciousness of his former actions two or twenty times.

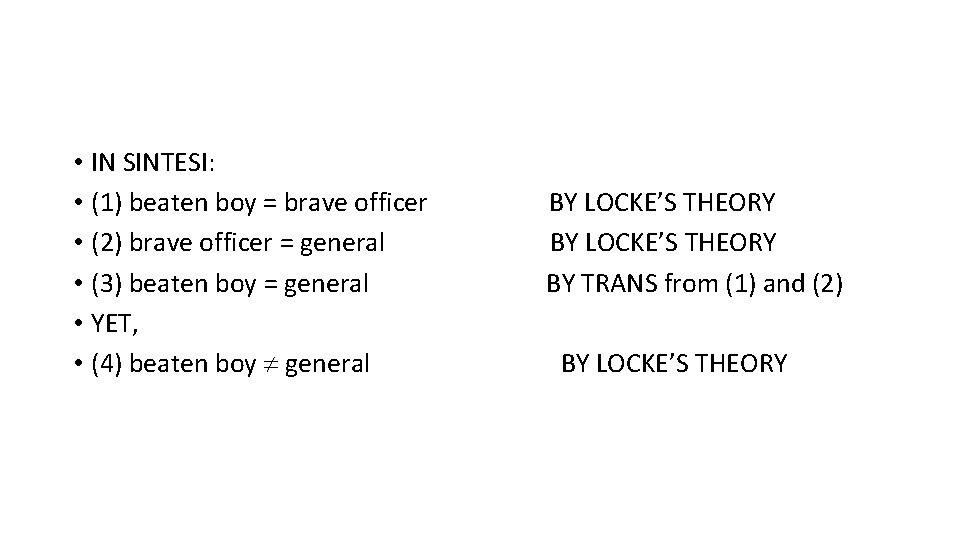

• Another consequence of this doctrine (which follows just • as necessarily, though Locke probably didn’t see it) is this: • A man may be and at the same time not be the person that • performed a particular action.

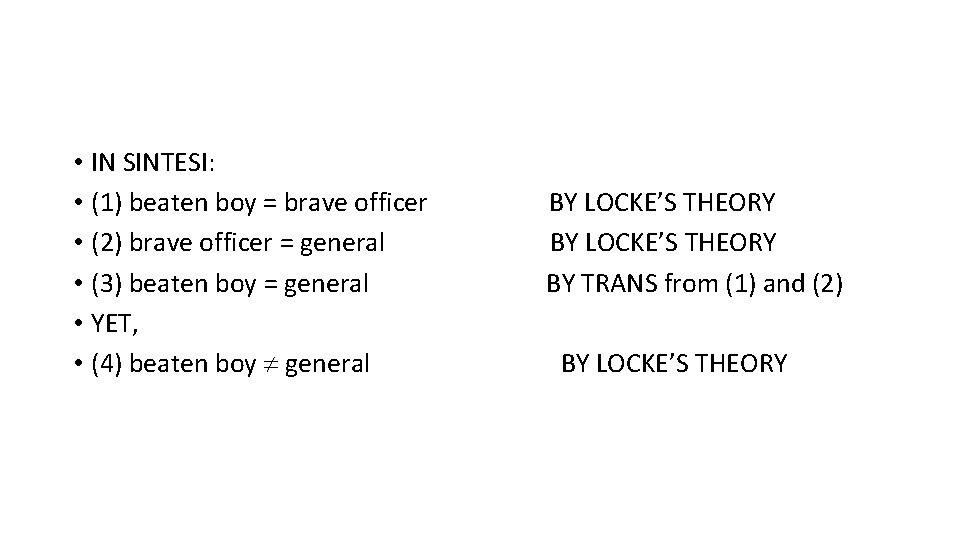

The brave officer case • • • Suppose that a brave officer • was beaten when a boy at school, for robbing an orchard, captures an enemy standard in his first battle, and • is made a general in advanced life. Given these suppositions, it follows from Locke’s doctrine that he who was beaten at school is the same person who captured the standard, and that he who captured the standard is the same person who was made a general. From which it follows—if there is any truth in logic!— [per la transitività dell’identità] that • the general is the same person as him who was beaten at school.

• But the general’s consciousness does not reach so far back • as his beating, and therefore according to Locke’s doctrine • • the general is not the person who was beaten. • So the general is and at the same time is not the person who • was beaten at school.

• IN SINTESI: • (1) beaten boy = brave officer BY LOCKE’S THEORY • (2) brave officer = general BY LOCKE’S THEORY • (3) beaten boy = general BY TRANS from (1) and (2) • YET, • (4) beaten boy general BY LOCKE’S THEORY

• Seguono 4 altre osservazioni sulla teoria di Locke • (1) Locke attributes to consciousness the conviction we • have of our past actions, as if a man could now be conscious • of what he did twenty years ago. It is impossible to make • sense of this unless ‘consciousness’ means memory, the only • faculty by which we have an immediate knowledge of our • past actions.

• Sometimes in informal conversation a man says he is • ‘conscious’ that he did such-and-such, meaning that he • distinctly remembers that he did it. In ordinary everyday • talk we don’t need to fix precisely the borderline between • consciousness and memory. But this ·imprecision· ought • to be avoided in philosophy • SALTIAMO QUALCHE RIGA

• The faculties of • • consciousness and • memory are chiefly distinguished by • this: • consciousness is an immediate knowledge of the • present, • memory is an immediate knowledge of the past. • SALTIAMO QUALCHE RIGA • So Locke’s notion of personal identity, stated properly, is • that personal identity consists in clear remembering. . [qui il testo è abbreviato (oltre che, come altrove, po’ modificato)]

• • • (2) In this doctrine, not only is • consciousness run together with • memory, but (even more strange) • personal identity is run together with • the evidence we have of our personal identity. … Consciousness is the testimony of one faculty; memory is the testimony of another faculty. To say that • the testimony is the cause of • the thing testified is surely absurd if anything is absurd, and Locke couldn’t have said it if he hadn’t confused the testimony with the thing testified. .

• (3) Isn’t it strange that the sameness or identity of a person • should consist in something that is continually changing, • and is never the same for two minutes? • … • Consciousness and every kind of thought is passing and • momentary, and has no continuous existence; so if personal • identity consisted in consciousness it would certainly follow • that no • man is the same • person any two moments of his • life; …

• (4) In his discussion of personal identity, Locke uses • many expressions that I find unintelligible unless he wasn’t • distinguishing • the sameness or identity that we ascribe to • an individual from • the identity which in everyday talk we • ascribe to many individuals of the same species. • When we say that pain and pleasure, consciousness and • memory, are the same in all men, this ‘same’ness can only • mean similarity, i. e. sameness of kind. [in termini contemporanei. “trope resemblance”]

• • • … The same kind or species of operation may occur in different men or in the same man at different times, but it is impossible for the same individual operation to occur in different men or in the same man at different times. … If our personal identity consists in consciousness, given that consciousness can’t be • the same individually for any two moments but only • of the same kind, it would follow that we are not for any two moments the same individual persons but the same kind of persons.

• As our consciousness sometimes ceases to exist—as • in sound sleep—our personal identity must cease with it, • according to Locke’s theory. He allows that a single thing • can’t have two beginnings of existence; so our identity would • be irrecoverably lost every time we stopped thinking, even if • only for a moment.

• Lezione 21 • 21 Nov. 2016

David Hume • Treatise of Human Nature (1739 -40) • Ci concentreremo sui passi riguardanti il sé e l’identità personale: • Book I (1739), part IV, sect. 2 + sect. 6 • Book III (1740), appendix • Prima però qualche informazione su Hume dalla voce “Hume” della SEP (di William Edward Morris e Charlotte R. Brown)

Dalla voce SEP su Hume • Generally regarded as one of the most important philosophers to write in English, David Hume (b. 1711, d. 1776) was also well known in his own time as an historian and essayist. A master stylist in any genre, his major philosophical works—A Treatise of Human Nature (1739– 1740), the Enquiries concerning Human Understanding (1748) and concerning the Principles of Morals (1751), as well as his posthumously published Dialogues concerning Natural Religion (1779)—remain widely and deeply influential. • Sfruttando la SEP, ripassiamo la sua terminologia …

Da SEP • He uses perception to designate any mental content whatsoever, and divides perceptions into two categories, impressions and ideas. • Impressions include sensations as well as desires, passions, and emotions. Ideas are “the faint images of these in thinking and reasoning” (T 1. 1/1). He thinks everyone will recognize his distinction, since everyone is aware of the difference between feeling and thinking. It is the difference between feeling the pain of your present sunburn and recalling last year's sunburn.

• Hume distinguishes two kinds of impressions: impressions of sensation, or original impressions, and impressions of reflection, or secondary impressions. Impressions of sensation include the feelings we get from our five senses as well as pains and pleasures, all of which arise in us “originally, from unknown causes” (T 1. 1. 2. 1/7). He calls them original because trying to determine their ultimate causes would take us beyond anything we can experience. Any intelligible investigation must stop with them

• Impressions of reflection include desires, emotions, passions, and sentiments. They are essentially reactions or responses to ideas, which is why he calls them secondary. Your memories of last year's sunburn are ideas, copies of the original impressions you had when the sunburn occurred. Recalling those ideas causes you to fear that you'll get another sunburn this year, to hope that you won't, and to want to take proper precautions to avoid overexposure to the sun.

• Perceptions—both impressions and ideas—may be either simple or complex. Complex impressions are made up of a group of simple impressions. My impression of the violet I just picked is complex. Among the ways it affects my senses are its brilliant purple color and its sweet smell. I can separate and distinguish its color and smell from the rest of my impressions of the violet. Its color and smell are simple impressions, which can't be broken down further because they have no component parts.

• Prima di passare al sé e all’identità personale in Hume, vediamo cosa dice Hume sull’identità in generale. • Leggiamo un passo tratto da Book I, part IV, sect. 2 Of Scepticism With Regard to the Senses

Da Treatise, Book I, part IV, sect. 2 • First, As to the principle of individuation; we may observe, that the view of any one object is not • sufficient to convey the idea of identity. For in that proposition, an object is the same with itself, if • the idea express’d by the word, object, were no ways distinguish’d from that meant by itself; we • really shou’d mean nothing, nor wou’d the proposition contain a predicate and a subject, which however • are imply’d in this affirmation. One single object conveys the idea of unity, not that of identity.

• On the other hand, a multiplicity of objects can never convey this idea, however resembling they • may be suppos’d. The mind always pronounces the one not to be the other, and considers them as • forming two, three, or any determinate number of objects, whose existences are entirely distinct and independent.

• Since then both number and unity are incompatible with the relation of identity, it must lie in something • that is neither of them. But to tell the truth, at first sight this seems utterly impossible. Betwixt • unity and number there can be no medium; no more than betwixt existence and non-existence. After • one object is suppos’d to exist, we must either suppose another also to exist; in which case we have • the idea of number: Or we must suppose it not to exist; in which case the first object remains at • unity.

• To remove this difficulty, let us have recourse to the idea of time or duration. I have already observ’d, that time, in a strict sense, implies succession, and that when we apply its idea to any unchangeable • object, ’tis only by a fiction of the imagination, by which the unchangeable object is • suppos’d to participate of the changes of the co-existent objects, and in particular of that of our perceptions.

• Lezione 22 • 22 Nov. 2016

calendario • Ultima lezione prevista per Lunedì 12 Dicembre

Da Part II. : Of the Ideas of Space and Time. • I know there are some who pretend, that the idea of duration is applicable in a proper sense to objects, • which are perfectly unchangeable; and this I take to be the common opinion of philosophers • as well as of the vulgar. But to be convinc’d of its falsehood we need but reflect on the foregoing • conclusion, that the idea of duration is always deriv’d from a succession of changeable objects, and • can never be convey’d to the mind by any thing stedfast and unchangeable.

• For it inevitably follows • from thence, that since the idea of duration cannot be deriv’d from such an object, it can never in • any propriety or exactness be apply’d to it, nor can any thing unchangeable be ever said to have • duration. Ideas always represent the objects or impressions, from which they are deriv’d, and can • never without a fiction represent or be apply’d to any other. By what fiction we apply the idea of • time, even to what is unchangeable, and suppose, as is common, that duration is a measure of rest as • well as of motion, we shall consider 8 afterwards

• This fiction of the imagination almost universally takes place; and ’tis by means of it, that • a single object, plac’d before us, and survey’d for any time without our discovering in it any interruption • or variation, is able to give us a notion of identity.

• For when we consider any two points of • this time, we may place them in different lights: We may either survey them at the very same instant; in which case they give us the idea of number, both by themselves and by the object; which • must be multiply’d, in order to be conceiv’d at once, as existent in these two different points of time:

• Or on the other hand, we may trace the succession of time by a like succession of ideas, and • conceiving first one moment, along with the object then existent, imagine afterwards a change in • the time without any variation or interruption in the object; in which case it gives us the idea of unity. • Here then is an idea, which is a medium betwixt unity and number; or more properly speaking, is • either of them, according to the view, in which we take it: And this idea we call that of identity.

• We • cannot, in any propriety of speech, say, that an object is the same with itself, unless we mean, that • the object existent at one time is the same with itself existent at another.

• By this means we make a difference, betwixt the idea meant by the word, object, and that meant by itself, without going the length of number, and at the same time without restraining ourselves to a strict and absolute unity.

• Thus the principle of individuation is nothing but the invariableness and uninterruptedness of any object, thro’ a suppos’d variation of time, by which the mind can trace it in the different periods of its existence, without any break of the view, and without being oblig’d to form the idea of multiplicity or number.

• Adesso passiamo a • BOOK I, Part IV, SECTION VI. • Of personal identity.

Da BOOK I, Part IV, SECTION VI (dall’inizio) • There are some philosophers, who imagine we are every moment intimately conscious of what we • call our Self; that we feel its existence and its continuance in existence; and are certain, beyond the • evidence of a demonstration, both of [0] its perfect identity and simplicity. The strongest sensation, the • most violent passion, say they, instead of distracting us from this view, only fix it the more intensely, • and make us consider their influence on self either by their pain or pleasure.

• To attempt a • farther proof of this were to weaken its evidence; since no proof can be deriv’d from any fact, of • which we are so intimately conscious; nor is there any thing, of which we can be certain, if we • doubt of this.

Sovrapposizione delle onde

Sovrapposizione delle onde Principio di archimede formule

Principio di archimede formule Segreteria montanari verona

Segreteria montanari verona Lezioni di tecnica delle costruzioni

Lezioni di tecnica delle costruzioni Scomposizione forze piano inclinato

Scomposizione forze piano inclinato Lezioni partecipate

Lezioni partecipate Sistema lineare impossibile esempio

Sistema lineare impossibile esempio Lezioni online unich

Lezioni online unich Momento di una coppia di forze zanichelli

Momento di una coppia di forze zanichelli Indici di dispersione

Indici di dispersione Dott armonico giuseppe

Dott armonico giuseppe Nad+ cos'è

Nad+ cos'è Liceo statale galileo galilei dolo

Liceo statale galileo galilei dolo Galilei dolo

Galilei dolo Accelerazione negativa

Accelerazione negativa Notazione scientifica esercizi zanichelli

Notazione scientifica esercizi zanichelli Color 01122008

Color 01122008 Nulla si crea nulla si distrugge in inglese

Nulla si crea nulla si distrugge in inglese Comparativi in inglese

Comparativi in inglese Riconoscimento certificazioni linguistiche unipd

Riconoscimento certificazioni linguistiche unipd Periodo.ipotetico inglese

Periodo.ipotetico inglese Materia religione in inglese

Materia religione in inglese Quadro generale in inglese

Quadro generale in inglese Fasi lunari in inglese

Fasi lunari in inglese Numeri in inglese da 1 a 20 pronuncia

Numeri in inglese da 1 a 20 pronuncia Inquadrature in inglese

Inquadrature in inglese Analisi preliminare in inglese

Analisi preliminare in inglese Traduttore italiano inglese

Traduttore italiano inglese Past simple forma passiva

Past simple forma passiva Piano didattico personalizzato in inglese

Piano didattico personalizzato in inglese Parti dellaereo

Parti dellaereo Stato sociale in inglese

Stato sociale in inglese Eseguito inglese

Eseguito inglese La parola bullismo deriva dall'inglese

La parola bullismo deriva dall'inglese Lesson 4 speaking

Lesson 4 speaking Caratteri mendeliani nell'uomo

Caratteri mendeliani nell'uomo Giacomo 1 stuart

Giacomo 1 stuart Inghilterra sistema scolastico

Inghilterra sistema scolastico Stop hunt grand canyon national

Stop hunt grand canyon national Tecniche traduzione inglese

Tecniche traduzione inglese Outcome measures traduzione

Outcome measures traduzione Present continuous futuro

Present continuous futuro Powerpoint sul riciclo scuola media

Powerpoint sul riciclo scuola media Ready for practice tests invalsi

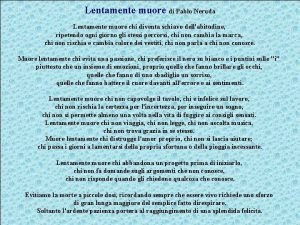

Ready for practice tests invalsi Poesia muore lentamente

Poesia muore lentamente