Incorporating Indigenous language perspectives in the new Australian

- Slides: 18

Incorporating Indigenous language perspectives in the new Australian curriculum Presentation to By Dr Jaky Troy Education, University of Canberra 18 September 2010, 9. 30 -12. 30 National Museum of Australia

How can we make a difference for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander students? By. . . http: //www. reconciliationsa. org. au/learn%20 map. html

Languages and the National Curriculum ACARA • I am co-writing the ‘National Languages Curriculum Shape Paper’ for the Australian Curriculum and Assessment Reporting Authority (ACARA). • It includes a central focus on inclusion of Australian languages, ie Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander languages in the curriculum. Australian languages are understood in the document as including contact languages, including Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Englishes. • ACARA will develop a national framework for teaching Australian languages from this paper.

Shape of the Australian curriculum: languages ‘The development of the initial advice paper for Languages has commenced. This paper provides advice on curriculum design and will be the subject of consultation at a national forum to be held in August. The initial advice will inform the Shape of the Australian Curriculum: Languages that, following a broad-based consultation, will be used to guide curriculum writers in the languages learning area. Associate Professor Angela Scarino was appointed as lead writer to complete this work. Dr Jakelin Troy has been recently appointed to assist her by writing the sections relating to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Languages. Dr Troy holds the position of Assistant Professor, Curriculum Studies, Faculty of Education, University of Canberra. Associate Professor Angela Scarino and Dr Jakelin Troy will draft the initial advice with the support of an advisory group. ’ http: //www. acara. edu. au/acara_update_30032010. html

cross curriculum perspectives 1. 2. 3. In developing the Australian curriculum, ACARA has identified three crosscurriculum perspectives which are to be represented in the learning areas in ways that are appropriate to that area. These perspectives are (as outlined in The Shape of the Australian Curriculum p. 13): Indigenous perspectives, which will be written into the national curriculum to ensure that all young Australians have the opportunity to learn about, acknowledge and respect the history and culture of Aboriginal people and Torres Strait Islanders a commitment to sustainable patterns of living which will be reflected in curriculum documents skills, knowledge and understandings related to Asia and Australia’s engagement with Asia. The curriculum documents will be explicit on how the perspectives are to be dealt with in each learning area and how links can be made between learning areas.

Language is an essential part of being Aboriginal On the Dharug language website http: //www. dharug. dalang. com. au created by Richard Green, traditional owner of the language, you can hear Aboriginal people in Redfern talking passionately about the critical importance of language to them as Aboriginal people.

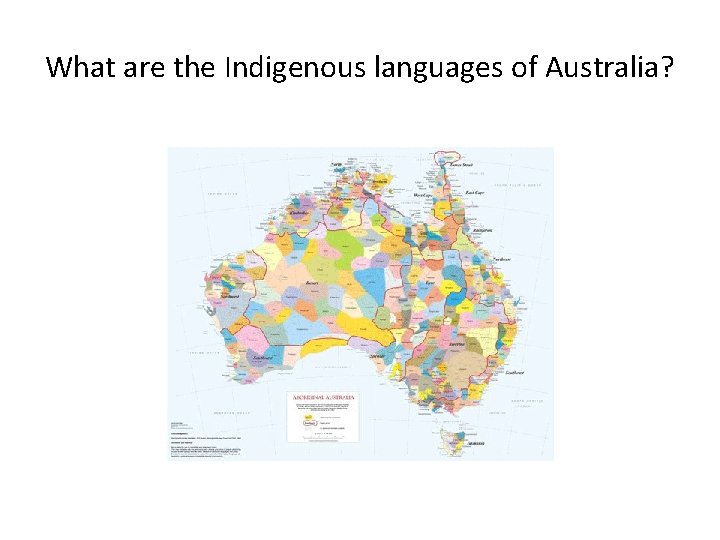

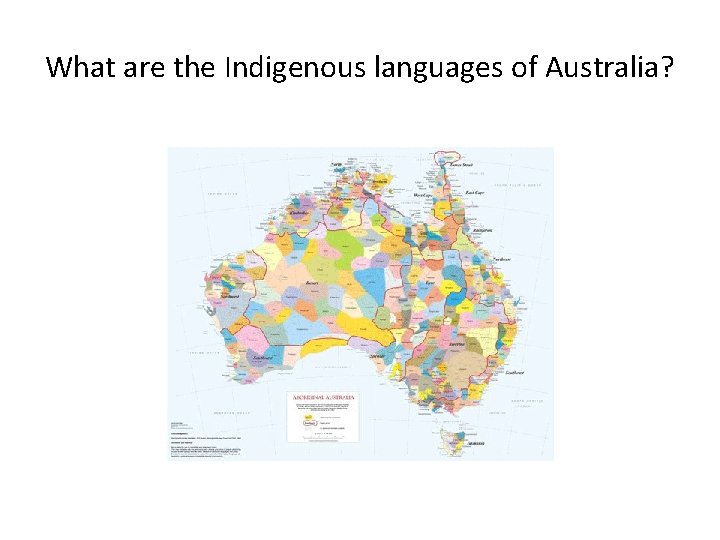

What are the Indigenous languages of Australia?

Ecology of the languages • Linguists estimate that there about 250 Australian languages and many more dialects of these languages • Of these there are now a small number, maybe even less than 30, which are still used as the first languages of everyday communication for their communities or ‘language owners’. Most of these languages are in the northern territory, South Australia, north western Australia, north Queensland the Torres Straits. • However, all over Australia the owners of the other languages are working to revitalise their languages and reclaim them as languages of everyday communication. • Languages that seemed to have no speakers only a few years ago now have active speaker/revitaliser communities. • For example, when I was researching Dharug, in the 1980 s, that language seemed to be completely moribund. Now it has its own website that you saw above (actually 2 websites because the historical documents for the language are also online see http: //williamdawes. org/), schools programs, you can download the language onto your phone and Richard Green and others regularly give public addresses in the language (and this is just a quick survey of its recent ecology)

The ‘other’ Indigenous languages of Australia: ‘deadly lingo, unna’ • Often put down, even by their own speakers, as being inferior to the ‘vernacular’ languages the ‘contact languages’ are the ‘other’ Indigenous languages of Australia. • These languages are the pidgins, creoles and Aboriginal Englishes that developed first in the colonial period of Australia history and continued to develop into the first or part of the repertoire of first languages of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. • Far from being ‘inferior’ languages these are dynamic and exciting communicative responses to the mix of languages and peoples that have made Australia the culturally diverse and linguistically rich environment in which we now live.

Pidgin • Pidgins are languages that develop when there is a population of people speaking between them 3 or more ‘mother tongues’ but not sharing any in common and who are unexpectedly ‘thrown together’. Typically this happens in, for example, an early colonial or a trading situation. • At first people respond with idiosyncratic linguistic responses such as speaking in unstable jargon. • However, when a jargon begins to stabilise and regular grammatical features and vocabulary are distinguishable this is the beginning ‘pidginisation’ and a new language. • For my doctoral thesis I investigated the development of the first pidgin language in the Pacific which had its inception in Sydney, the first European (British) colony in the Pacific. A pidgin language appears to have developed very quickly, within the first decade of the colony. The mix was, at least, English, Irish and Australian languages. • This first pidgin in Australia, indeed the Pacific, I called ‘NSW Pidgin’. • NSW Pidgin appears to be the base for all other Australian pidgins and possibly all other Pacific pidgins. • It is also the basis for all Australian creole languages and Aboriginal Englishes.

Creole • When children grow up speaking a pidgin as their first or one of their first languages and it becomes a ‘mother tongue’ the pidgin then ‘creolises’. • The word ‘creole’ was adapted by linguists from the same word which was coined to refer to people of French origin born in colonial French countries. These ‘creoles’ are French but with local adaptations. • As successive generations grow up speaking a creolising pidgin the communicative repertoire and complexity of the language expands. It becomes a ‘natural’ language in the sense that all languages with long linguistic history are complex and able to be used for all communicative purposes. • In Australia it is unlikely that any ‘contact languages’ are still ‘pidgins’, all the pidgins have creolised. Their names reflect this fact, so we have, for example, ‘Kriol’ of the Northern Territory and ‘Broken’ or ‘Torres Strait Creole’.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Englishes • Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Englishes are usually described as varying from ‘heavy’ to ‘light’. • The ‘heaviest’ forms are so far removed from Standard Australian English (SAE) that they might be unintelligible to an English speaker, calling into question their status as dialects or varieties of English. • The ‘lightest’ forms are so close to SAE that they call into question what is it about them that sets them apart. • A recent study of Aboriginal Englishes in Canberra preschools found that children were not operating in an obviously Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander variety of English. However, they were affected by the lack of program content specific to their cultural background. So children might sound like any other preschool child but what they are thinking and talking about is different and is based on their own cultural background. (University of New England’s Dr Liz Ellis led the research – ACTAE Review and research the impact of Aboriginal English (or Torres Strait Creole) on learning outcomes for Indigenous children in ACT preschools and preschool programs. Funded by the ACT Department of Education and Training. http: //www. une. edu. au/staff/eellis 4. php)

Engaging Aboriginal children with language they understand use everyday Yirra and her deadly dog, Demon by Anita Heiss and the students of La Perouse Public School (2007, Sydney: Allen and Unwin) is of the best books I have seen lately that uses ‘lingo’. Dr Anita Heiss is a member of the Wiradjuri nation of central NSW and is a high profile author, poet, social commentator and cultural activist. Kids at La Perouse Public School http: //www. laperouse-p. schools. nsw. edu. au/sws/view/36302. node

Language as cultural expression • Even more importantly, in this book Anita uses language and cultural context as a basis for engaging Aboriginal children with reading, as a springboard for their own writing and as a great starting point for discussion and exploring their own communities. • This book could be read by Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander children anywhere in Australia and it would resonate with them on many counts – for its connections between people, between people and ‘country’, the style of the language, the pace of life and the cultural knowledge that is continuously and easily being passed between adults and children. ‘It’s a quick walk across the Mission to her own home in Goolagong Place. As she walks, Yirra thinks about the stories her grandparents have told her about how Koories were forced to live on the Mission in the old days because the government said so. Now the Mish is home and they wouldn’t live anywhere else – its so close to the beach and all their friends. ’ (Heiss et al 2007: 14) People and country what else do we need? ! • For us as educators the school gets good press too, which is always positive in building student, teacher and school relationships. “Yirra wakes up on Thursday and springs out of bed. . . its the day of her class excursion to Botany Bay National Park. Yirra’s in such a rush to get to school she almost forgets her cap and she doesn’t even stop to look for her missing i. Pod. . When the old bus finally pulls in to Botany Bay, Rodney, an Aboriginal Discovery Ranger and David the Sites Officer from the local Aboriginal Land Council are waiting for them. They show them heaps of important cultural sites. The kids get pretty excited when Rodney and David show them where the local Koories used to sharpen their axes. The boys all jostle each other to get a good view of the axe-grinding grooves. Yirra’s more interested in the middins. . ’How was the excursion, Yirra? ’ ‘Too deadly, we had a great time. ’” (pp 61 -62)

Aboriginal English features of the text • The text is largely in standard English but throughout the book the characters use typically Aboriginal English address forms such as ‘Aunty’ and ‘Uncle’, ‘Nan’ and ‘Pop’ as extended respect terms. ‘Uncle Laddie throws the boomerang. . . The crowd gathered around the stall clap at Uncle Laddie’s throwing style and one of the local Elders, Aunty Beryl, says, ‘He throws it just like World Champion Boomerang Thrower Uncle Joe Timbery used to. ’ (Heiss et all 2007: 23) • We all live in ‘mobs’ and things are grouped in ‘mobs’, “’Our mob originally came from Wreck Bay, down the south coast near Jervis Bay, ’ Pop Eddy tells the class. ” (p 32) • Anything that is of value and loved is ‘deadly’ and we are all ‘fellas’. So Yirra and her friends exchange the following: - “‘I’m staying at Grandma Trish’s tonight, you fellas wanna stay too? ’ Yirra asks. . . ‘Is she making her deadly chocolate-chip cookies? They’re the best. ’ Mary looks at Yirra and they both say ‘Mmmmmmm’ at the same time and then laugh. ” (pp 11 -12) • The names in the book are all typically Aboriginal – typical now. So the kids are ‘Yirra, Jarrod, and Kilarlia. . . ’ etc (p 41) and Yirra’s name means ‘sun’. • At the end of the book Anita kindly includes a glossary with further insight into Lingo and cultural terms.

Strategies for including contact languages into teaching programs Neil Harrison’s ‘Teaching and learning in Indigenous education’ (2010, Melbourne: Oxford University Press) is full of wisdom on all aspects of education for and about Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.

Wisdom from Neil Harrison • ‘Aboriginal English is the language spoken at home by many Aboriginal students. It is also the first language for most Aboriginal people in Australia (Eades 2004). Aboriginal English is not just a way of talking among Aboriginal people; it is a way of thinking and behaving. Aboriginal English helps Aboriginal people to pass on their culture from adult to child. The words carry the culture. The dialect is often used by its speakers as a way of maintaining a group identity. Speaking Aboriginal English brings like-minded people together, but it also excludes others. ’ (Harrison, 2010: 85) • I agree with Harrison that there are many benefits in learning two dialects together, and it is well demonstrated that learning two languages together is an advantage for life for all students. So learning a creole or a dialect of and Indigenous English and SAE can only benefit Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander students and their fellow students. • Harrison quotes Jeff Siegel (a pidgin-creolist I have known throughout my career and partner of Diana Eades who is famous for her work on Aboriginal Englishes is writing ‘that when students learn two dialects together, they are in a position to examine the patterns of speech, rules of grammar, vocabulary, sounds, and tonal features of their own dialect and observe how they differ from those of the second dialect (or the dialect of other students). A discussion of these differences can allow students to separate the two dialects, rather than confuse them because the dialects are perceived to be similar. Students’ first dialects would provide them with a metalanguage, a way of talking about and analysing standard English). This would help students to reduce the interference from Aboriginal English in the acquisition of Standard English, rather than increase the interference, as is sometimes feared. ’ (p 92)

Recognise and teach Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Englishes and creoles • Harrison works through ‘four strategies for incorporating Aboriginal English into teaching programs’ (see pp 92 -96). • My personal preference is for the bold and inclusive fourth strategy that advocates for schools recognising Aboriginal English through the whole school in all contexts and teaching the differences between Aboriginal English dialects and SAE to all students. • This strategy bestows a dignity and value to the English dialects used by Aboriginal students and mitigates against the endless deficit models applied to so many aspects of Aboriginal students’ performance at school. • Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Englishes and creoles are not deficit dialects or languages they are rich communicative systems that if treated as such within the school context can assist your students to develop proficiency in spoken and written SAE.