In the name of Allah Introduction to Robotics

In the name of Allah Introduction to Robotics

Introduction to Robotics o Leila Sharif o l_sharif@sharif. edu http: //ce. sharif. edu/courses/84 -85/1/ce 516/ o Lecture #4: Effectors and Actuators Introduction to Robotics

Lecture Outline q A brief history of robotics q q Feedback control Cybernetics Artificial Intelligence (AI) Early robotics q Robotics today q Why is robotics hard? q Degrees of Freedom (DOF) q holonomicity, redundancy q Legged locomotion q stability (static and dynamic) q polygon of support q Wheeled locomotion q Trajectory/motion planning Introduction to Robotics

Feedback Control q Feedback: continuous monitoring of the sensors and reacting to their changes. q Feedback control = self-regulation q Two kinds of feedback: q Positive q Negative q The basis of control theory Introduction to Robotics

- and + Feedback q Negative feedback q acts to regulate the state/output of the system q e. g. , if too high, turn down, if too low, turn up q thermostats, bodies, robots. . . q Positive feedback q acts to amplify the state/output of the system q e. g. , the more there is, the more is added q stock market, . . . Introduction to Robotics

Cybernetics q Pioneered by Norbert Wiener (1940 s) q (From Greek “steersman” of steam engine) q Marriage of control theory (feedback control), information science and biology q Seeks principles common to animals and machines, especially for control and communication q Coupling an organism and its environment (situatedness) Introduction to Robotics

Early Artificial Intelligence q “Born” in 1955 at Dartmouth q “Intelligent machine” would use internal models to search for solutions and then try them out (M. Minsky) => deliberative model! q Planning became the tradition q Explicit symbolic representations q Hierarchical system organization q Sequential execution Introduction to Robotics

Artificial Intelligence (AI) q Early AI had a strong impact on early robotics q Focused on knowledge, internal models, and reasoning/planning q Basis of deliberative control in early robots Introduction to Robotics

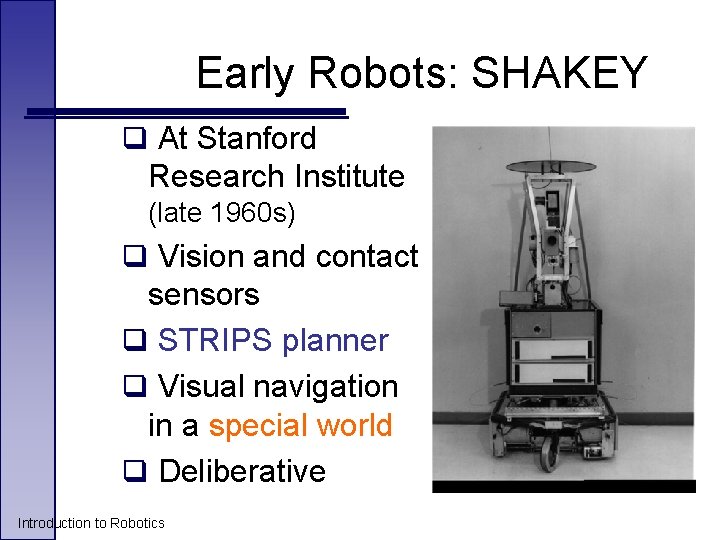

Early Robots: SHAKEY q At Stanford Research Institute (late 1960 s) q Vision and contact sensors q STRIPS planner q Visual navigation in a special world q Deliberative Introduction to Robotics

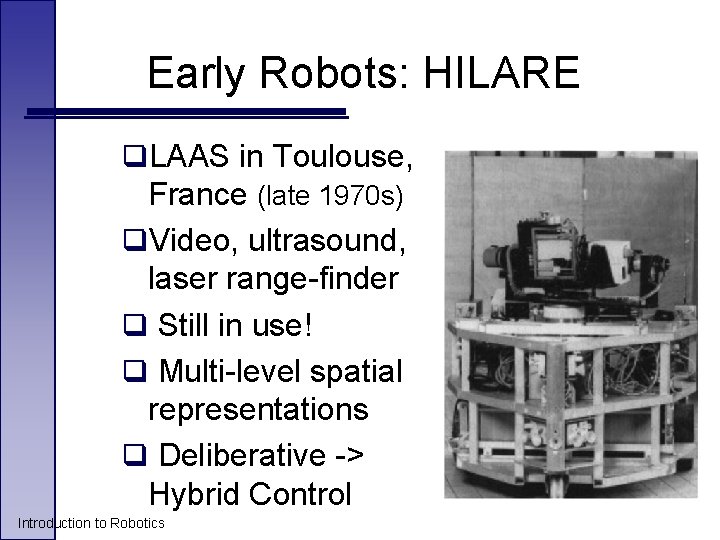

Early Robots: HILARE q. LAAS in Toulouse, France (late 1970 s) q. Video, ultrasound, laser range-finder q Still in use! q Multi-level spatial representations q Deliberative -> Hybrid Control Introduction to Robotics

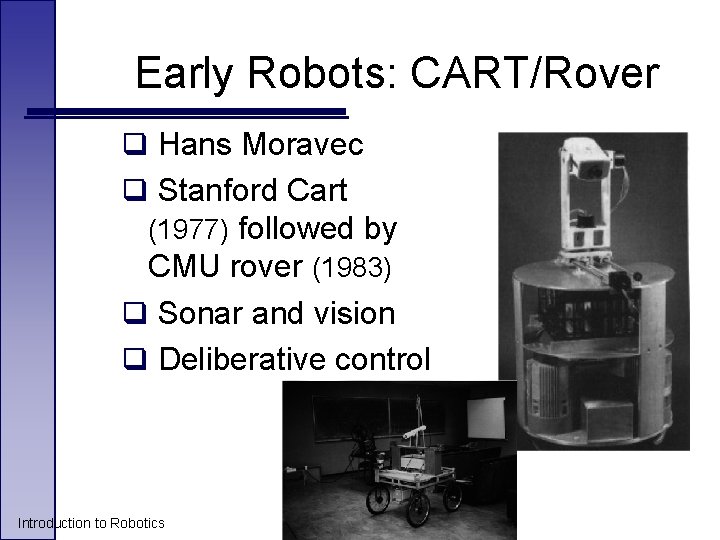

Early Robots: CART/Rover q Hans Moravec q Stanford Cart (1977) followed by CMU rover (1983) q Sonar and vision q Deliberative control Introduction to Robotics

Robotics Today q Assembly and manufacturing (most numbers of robots, least autonomous) q q q q Materials handling Gophers (hospitals, security guards) Hazardous environments Remote environments Surgery (brain, hips) Tele-presence and virtual reality Entertainment Introduction to Robotics

Why is Robotics hard? Introduction to Robotics

Why is Robotics hard? q Sensors are limited and crude q Effectors are limited and crude q State (internal and external, but mostly external) is partiallyobservable q Environment is dynamic (changing over time) q Environment is full of potentiallyuseful (and useless) information Introduction to Robotics

Key Issues q Grounding in reality: not just planning in an abstract world q Situatedness (ecological dynamics): tight connection with the environment q Embodiment: having a body q Emergent behavior: interaction with the environment q Scalability: increasing task and environment complexity Introduction to Robotics

Definition of Effector q An effector is any device that has an effect on the environment. q A robot’s effectors are used to purposefully effect the environment. q E. g. , legs, wheels, arms, fingers. . . q The role of the controller is to get the effectors to produce the desired effect on the environment, based on the robot’s task. Introduction to Robotics

Definition of Actuator q An actuator is the actual mechanism that enables the effector to execute an action. q E. g, electric motors, hydraulic or pneumatic cylinders, pumps… q Actuators and effectors are not the same thing. q Incorrectly thought of the same; “whatever makes the robot act” Introduction to Robotics

Degrees of Freedom q Most simple actuators control a single degree of freedom (DOF) q Think of DOFs as ways in which a motion can be made (e. g. , up-down, left-right, in-out) q E. g. , a motor shaft controls one rotational DOF; a sliding part on a plotter controls one translational DOF. Introduction to Robotics

Counting DOF q A free body in space has 6 DOF q 3 are translational (x, y, z) q 3 are rotational (roll, pitch, and yaw) q Every robot has a specific number of DOF q If there is an actuator for every DOF, then all of the DOF are controllable q Usually not all DOF are controllable q This makes robot control harder Introduction to Robotics

Example: DOF of a Car q A car has 3 DOF: position (x, y) and orientation (theta) q Only 2 DOF are controllable q driving: through the gas pedal and the forward-reverse gear q steering: through the steering wheel q Since there are more DOF than are controllable, there are motions that cannot be done, like moving sideways (that’s why parallel parking is hard) Introduction to Robotics

Actuators and DOFs q We need to make a distinction between what an actuator does (e. g. , pushing the gas pedal) and what the robot does as a result (moving forward) q A car can get to any 2 D position but it may have to follow a very complicated trajectory q Parallel parking requires a discontinuous trajectory w. r. t. velocity, i. e. , the car has to stop and go Introduction to Robotics

Holonomicity q When the number of controllable DOF is equal to the total number of DOF on a robot, it is holonomic. q If the number of controllable DOF is smaller than total DOF, the robot is non-holonomic. q If the number of controllable DOF is larger than the total DOF, the robot is redundant. Introduction to Robotics

Redundancy q A human arm has 7 DOF (3 in the shoulder, 1 in the elbow, 3 in the wrist), all of which can be controlled. q A free object in 3 D space (e. g. , the hand, the finger tip) can have at most 6 DOF! q => There are redundant ways of putting the hand at a particular position in 3 D space. q This is the core of why manipulations is very hard! Introduction to Robotics

Uses of Effectors q Two basic ways of using effectors: q to move the robot around =>locomotion q to move other object around =>manipulation q These divide robotics into two mostly separate categories: q mobile robotics q manipulator robotics Introduction to Robotics

Locomotion q Many different kinds of effectors and actuators are used for locomotion: q legs (walking, crawling, climbing, jumping, hopping…) q wheels (rolling) q arms (swinging, crawling, climbing…) q flippers (swimming) q Most animals use legs, but most mobile robots use wheels, why? Introduction to Robotics

Stability q Stability is a necessary property of mobile robots q Stability can be q static (standing w/o falling over) q dynamic (moving w/o falling over) q Static stability is achieved through the mechanical design of the robot q. Dynamic stability is achieved through control Introduction to Robotics

More on Stability q E. g. , people are not statically stable, but are dynamically stable! It takes active control to balance. This is mostly unconscious. q Static stability becomes easier with more legs. q To remain stable, a robot’s center of gravity (COG) must fall under its polygon of support (the area of the projection of its points of contact onto the surface) Introduction to Robotics

Polygon of Support q In two-legged robots/creatures, the polygon of support is very small, much smaller than the robot itself, so static stability is not possible (unless the feet are huge!) q As more legs are added, and the feet spread out, the polygon gets larger q Three-legged creatures can use a tripod stance to be statically stable Introduction to Robotics

Statically Stable Walking q Three legs are enough to balance, but what about walking? q If a robot can stay continuously balanced while walking, it employs statically stable walking q Impossible with 3 legs; as soon as one is off the ground, only 2 are left, which is unstable q How many legs are needed for statically stable walking? Introduction to Robotics

Good Numbers of Legs q Since it takes 3 legs to be statically stable, it takes at least 4 to walk statically stable q Various such robots have been built q 6 legs is the most popular number as they allow for a very stable walking gait, the tripod gait q 3 legs are kept on the ground, while the other 3 are moved forward Introduction to Robotics

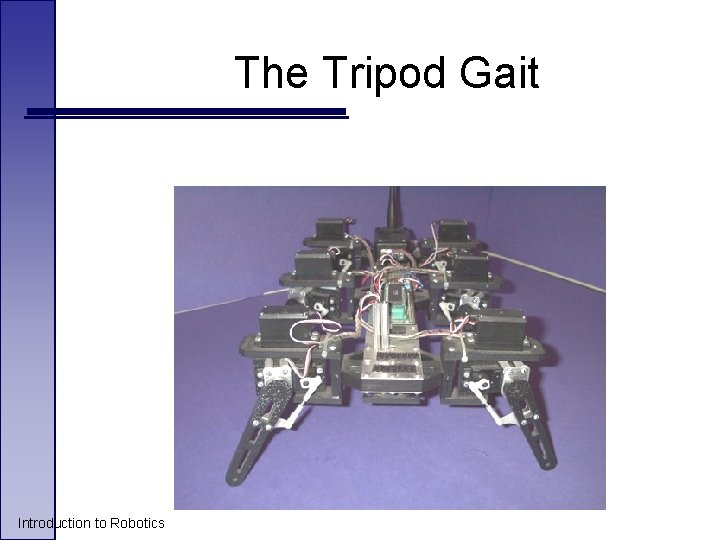

The Tripod Gait Introduction to Robotics

The Tripod Gait q If the same three legs move at a time, this is called the alternating tripod gait q if the legs vary, it is called the ripple gait q All times, a triangle of support stays on the ground, and the COG is in it q This is very stable and thus used in most legged robots Introduction to Robotics

Tripod Gait in Biology q Cockroaches and many other 6 -legged insects use the alternating tripod gait q Note: numerous insects have 6 legs q Insects with more than 6 legs (e. g. , centipedes and millipedes), use the ripple gate q Insects can also run very fast by letting go of the ground completely every once in a while, and going airborne… Introduction to Robotics

Dynamic Stability q Statically stable walking is very energy inefficient q As an alternative, dynamic stability enables a robot to stay up while moving q This requires active control (i. e. , the inverse pendulum problem) q Dynamic stability can allow for greater speed, but requires harder control Introduction to Robotics

Wheels v. Legs q Because balance is such a hard control problem, most mobile robots have wheels, not legs, and are statically stable q Wheels are more efficient than legs, and easier to control q There are wheels in nature, but legs are by far more prevalent, though in terms of population sizes, more than 2 legs (i. e. , insects abound) Introduction to Robotics

Varieties of Wheels q Wheels are the locomotion effector of choice in most mobile robots q Wheels can be as innovative as legs q size and shape variations q tire shapes and patterns q tracks q wheels within wheels and cylinders q different directions of rotation q. . . Introduction to Robotics

Wheels and Holonomicity q Having wheels does not imply holonomicity q 2 or 4 -wheeled robots are not usually holonomic q A popular and efficient design involves 2 differentially-steerable wheels and a passive caster Introduction to Robotics

Differential Steering Differential steering means that the two (or more) wheels can be steered separately (individually) q If one wheel can turn in one direction and the other in the opposite direction, the robot can spin in place q This is very helpful for following arbitrary trajectories q Tracks are often used (e. g. , tanks) q Introduction to Robotics

Trajectories q In locomotion we can be concerned with: q getting to a particular location q following a particular trajectory (path) q Following an arbitrary given trajectory is harder, and it is impossible for some robots (depending on their DOF) q For others, it is possible, but with discontinuous velocity (stop, turn, and then go again) Introduction to Robotics

Trajectory Planning q A large area of traditional robotics is concerned with following arbitrary trajectories q Why? Because planning can be used to compute optimal (and thus arbitrary) trajectories for a robot to follow to get to a particular goal location q Practical robots may not be so concerned with specific trajectories as with just getting to the goal location Introduction to Robotics

More Trajectory Planning q Trajectory planning is a computationally complex process q All possible trajectories must be found (by using search) and evaluated q Since robots are not points, their geometry (i. e. , turning radius) and steering mechanism (holonomicity properties) must be taken into account q This is also called motion planning Introduction to Robotics

- Slides: 41