Imaging for Pediatric Headache Clinical Algorithms to Guide

- Slides: 9

Imaging for Pediatric Headache: Clinical Algorithms to Guide Imaging Decision Making Developed and Contributed by: Emory University School of Medicine Emory University Department of Radiology and Imaging Sciences Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta (Egleston), Department of Radiology Algorithm Development Background Nadja Kadom, MD Associate Professor, Emory University School of Medicine Director of Pediatric Neuroradiology and Director of Quality, Department of Radiology at Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta (CHOA, Egleston) Our goal for this project is to guide imaging use in children with headaches through visual representation of evidence-based clinical algorithms. We identified three types of headache in need of guidance: general, trauma, infection, and sinus headaches. We developed an algorithm for each type based on existing consensus statements and clinical practice guidelines by professional medical societies, including the American College of Radiology Appropriateness Criteria®. The information was conveyed as visual algorithms featuring clinical yes-no decision trees that ultimately lead to either an imaging recommendation or an alternative workup without imaging. Each algorithm was reviewed by a specialist in the field at our institution: neurology for the general algorithms, emergency medicine for the trauma algorithm, otolaryngology for the sinus algorithm, and neuroradiology for all algorithms. These specialists along with community pediatricians and pediatric specialists provided feedback that resulted in modifications and ultimately algorithm approval. We are sharing the initial and the adapted algorithms as a starting point for practitioners throughout the U. S. who would like to adapt these to their local practice needs. The algorithms represent the state of evidence in 2019 and a process for continuous monitoring of emerging evidence and changes to the algorithms should be implemented. The algorithms incorporate clinical as well as radiologic information, cover a broad spectrum of pediatric headache, and can be adapted to multiple practice contexts (e. g. , primary care office, emergency department, inpatient). For example, during our adaptation process the “infection” algorithm was folded into the general algorithm because the next step would be imaging or a lumbar puncture and those procedures are not performed in our community pediatrician offices and would require referral to the hospital as the next step. Also, we modified red flags for headache according to our neurologists’ practice preferences, although some of these changes are not supported (yet) by scientific evidence. The adapted algorithms are currently part of a quality improvement project in our community where we are tracking various interventions geared towards improved imaging use, starting with educating referring physicians and providing access to these algorithms. I encourage other pediatric radiologists to consider similar projects within their healthcare setting to include using an R-SCAN quality improvement project to track progress.

Algorithm Disclaimer The algorithms in their current form are not intended for clinical use, instead they should be reviewed and adapted to local practice needs and local expert opinions. Both the original algorithms and the post-interdisciplinary team review adopted algorithms are presented to demonstrate changes that may result from working with a multi-disciplinary team on local adaption. Implementing the Tools Algorithms: • Assemble interdisciplinary teams • Review and revise algorithms as desired • Implement as guidance materials Associated Quality Improvement Project: • Set SMART goals: Specific, Measurable, Attainable, Relevant and Timely • Measure baseline and outcomes after algorithm implementation and adoption by all stakeholders • Use continuous improvement methodology to achieve the desired results • Use an R-SCAN QI Project template to track progress for participants to earn 20 performance improvement CME. Contact: rscaninfo@acr. org for more information.

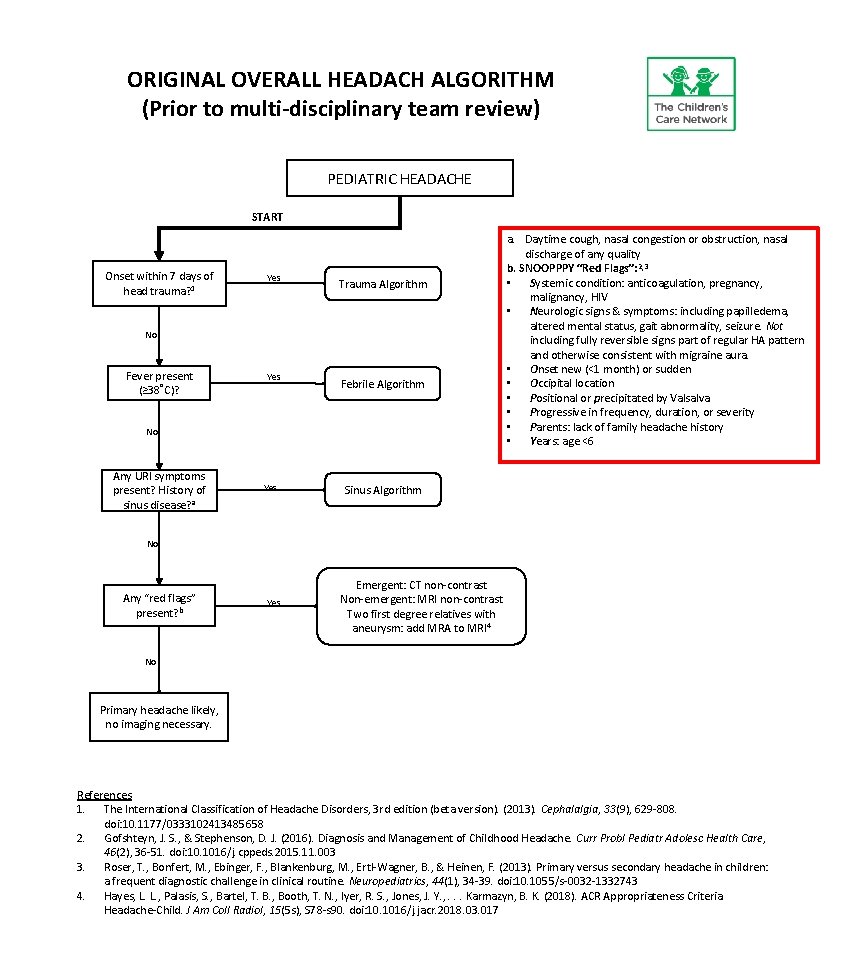

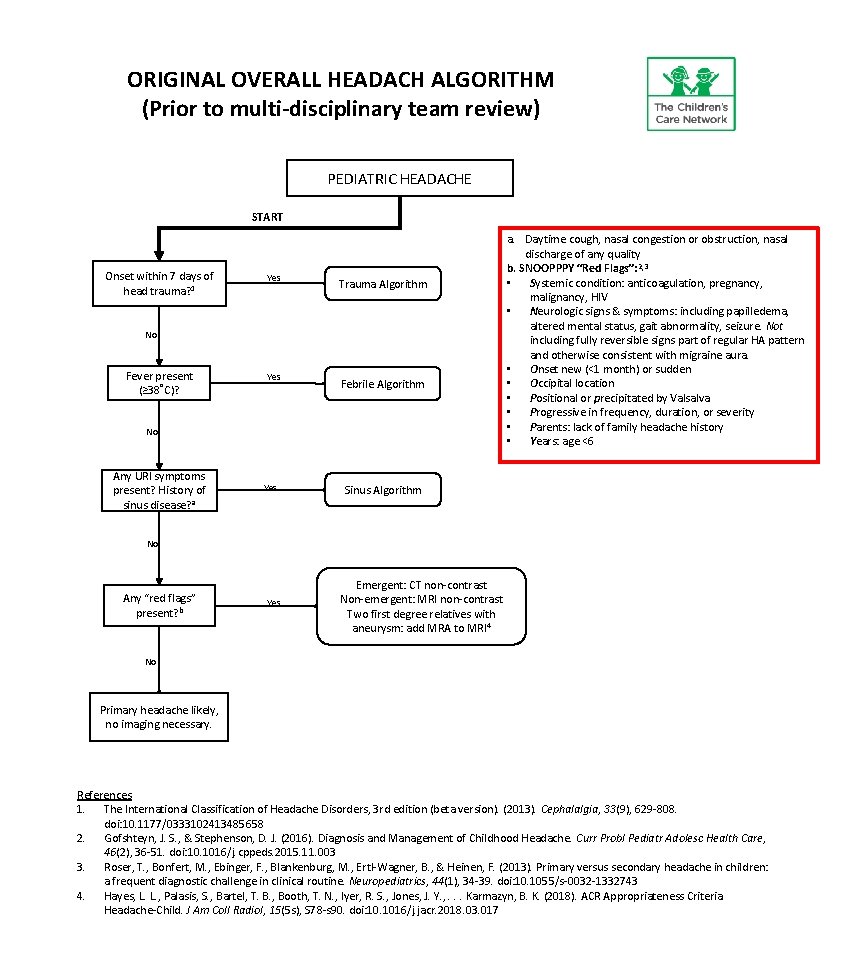

ORIGINAL OVERALL HEADACH ALGORITHM (Prior to multi-disciplinary team review) PEDIATRIC HEADACHE START Onset within 7 days of head trauma? 1 Yes Trauma Algorithm No Fever present (≥ 38˚C)? Yes Febrile Algorithm No Any URI symptoms present? History of sinus disease? a Yes a. Daytime cough, nasal congestion or obstruction, nasal discharge of any quality b. SNOOPPPY “Red Flags”: 2, 3 • Systemic condition: anticoagulation, pregnancy, malignancy, HIV • Neurologic signs & symptoms: including papilledema, altered mental status, gait abnormality, seizure. Not including fully reversible signs part of regular HA pattern and otherwise consistent with migraine aura. • Onset new (<1 month) or sudden • Occipital location • Positional or precipitated by Valsalva • Progressive in frequency, duration, or severity • Parents: lack of family headache history • Years: age <6 Sinus Algorithm No Any “red flags” present? b Yes Emergent: CT non-contrast Non-emergent: MRI non-contrast Two first degree relatives with aneurysm: add MRA to MRI 4 No Primary headache likely, no imaging necessary. References 1. The International Classification of Headache Disorders, 3 rd edition (beta version). (2013). Cephalalgia, 33(9), 629 -808. doi: 10. 1177/0333102413485658 2. Gofshteyn, J. S. , & Stephenson, D. J. (2016). Diagnosis and Management of Childhood Headache. Curr Probl Pediatr Adolesc Health Care, 46(2), 36 -51. doi: 10. 1016/j. cppeds. 2015. 11. 003 3. Roser, T. , Bonfert, M. , Ebinger, F. , Blankenburg, M. , Ertl-Wagner, B. , & Heinen, F. (2013). Primary versus secondary headache in children: a frequent diagnostic challenge in clinical routine. Neuropediatrics, 44(1), 34 -39. doi: 10. 1055/s-0032 -1332743 4. Hayes, L. L. , Palasis, S. , Bartel, T. B. , Booth, T. N. , Iyer, R. S. , Jones, J. Y. , . . . Karmazyn, B. K. (2018). ACR Appropriateness Criteria Headache-Child. J Am Coll Radiol, 15(5 s), S 78 -s 90. doi: 10. 1016/j. jacr. 2018. 03. 017

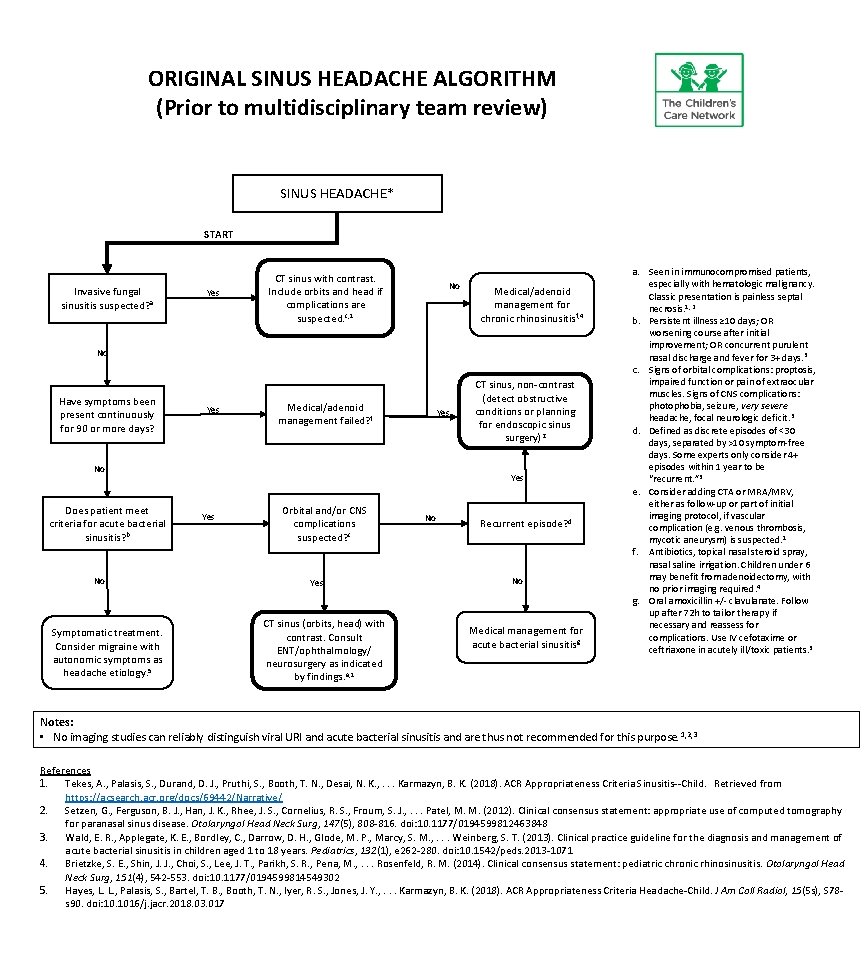

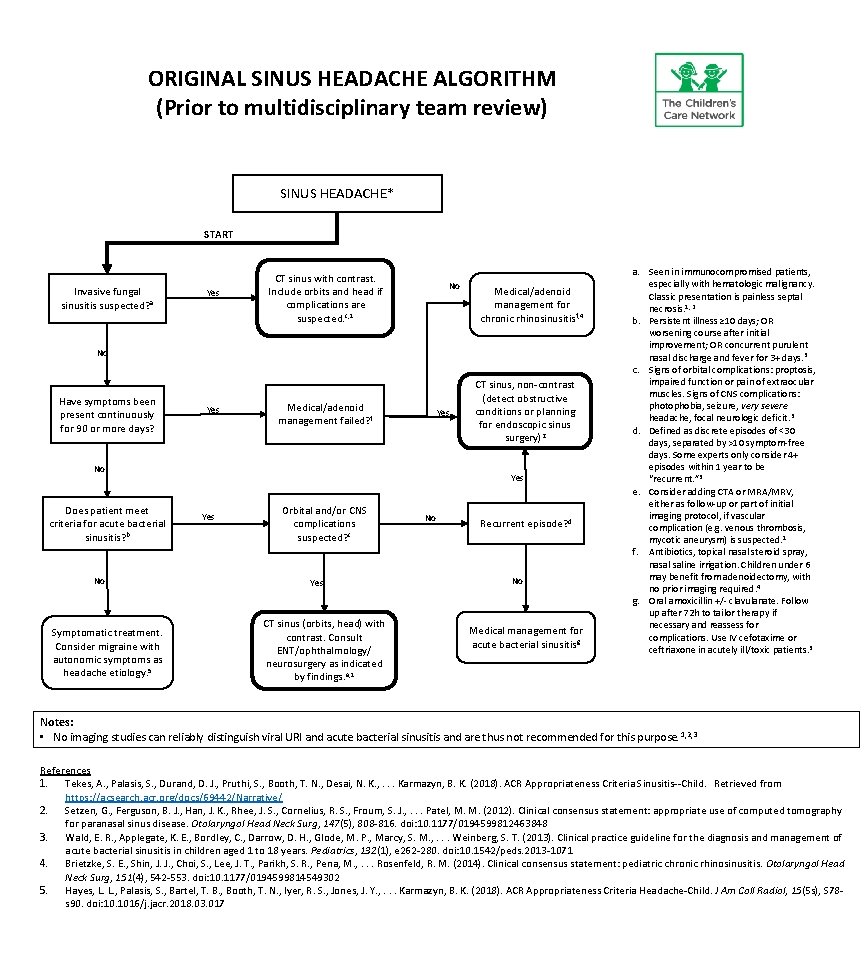

ORIGINAL SINUS HEADACHE ALGORITHM (Prior to multidisciplinary team review) SINUS HEADACHE* START Invasive fungal sinusitis suspected? a Yes CT sinus with contrast. Include orbits and head if complications are suspected. c, 1 No Medical/adenoid management for chronic rhinosinusitis f, 4 No Have symptoms been present continuously for 90 or more days? Yes Medical/adenoid management failed? f Yes No Does patient meet criteria for acute bacterial sinusitis? b No Symptomatic treatment. Consider migraine with autonomic symptoms as headache etiology. 5 CT sinus, non-contrast (detect obstructive conditions or planning for endoscopic sinus surgery)2 Yes Orbital and/or CNS complications suspected? c Yes CT sinus (orbits, head) with contrast. Consult ENT/ophthalmology/ neurosurgery as indicated by findings. e, 1 No Recurrent episode? d No Medical management for acute bacterial sinusitisg a. Seen in immunocompromised patients, especially with hematologic malignancy. Classic presentation is painless septal necrosis. 1, 2 b. Persistent illness ≥ 10 days; OR worsening course after initial improvement; OR concurrent purulent nasal discharge and fever for 3+ days. 3 c. Signs of orbital complications: proptosis, impaired function or pain of extraocular muscles. Signs of CNS complications: photophobia, seizure, very severe headache, focal neurologic deficit. 3 d. Defined as discrete episodes of <30 days, separated by >10 symptom-free days. Some experts only consider 4+ episodes within 1 year to be “recurrent. ” 3 e. Consider adding CTA or MRA/MRV, either as follow-up or part of initial imaging protocol, if vascular complication (e. g. venous thrombosis, mycotic aneurysm) is suspected. 1 f. Antibiotics, topical nasal steroid spray, nasal saline irrigation. Children under 6 may benefit from adenoidectomy, with no prior imaging required. 4 g. Oral amoxicillin +/- clavulanate. Follow up after 72 h to tailor therapy if necessary and reassess for complications. Use IV cefotaxime or ceftriaxone in acutely ill/toxic patients. 3 Notes: • No imaging studies can reliably distinguish viral URI and acute bacterial sinusitis and are thus not recommended for this purpose. 1, 2, 3 References 1. Tekes, A. , Palasis, S. , Durand, D. J. , Pruthi, S. , Booth, T. N. , Desai, N. K. , . . . Karmazyn, B. K. (2018). ACR Appropriateness Criteria Sinusitis--Child. Retrieved from https: //acsearch. acr. org/docs/69442/Narrative/ 2. Setzen, G. , Ferguson, B. J. , Han, J. K. , Rhee, J. S. , Cornelius, R. S. , Froum, S. J. , . . . Patel, M. M. (2012). Clinical consensus statement: appropriate use of computed tomography for paranasal sinus disease. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg, 147(5), 808 -816. doi: 10. 1177/0194599812463848 3. Wald, E. R. , Applegate, K. E. , Bordley, C. , Darrow, D. H. , Glode, M. P. , Marcy, S. M. , . . . Weinberg, S. T. (2013). Clinical practice guideline for the diagnosis and management of acute bacterial sinusitis in children aged 1 to 18 years. Pediatrics, 132(1), e 262 -280. doi: 10. 1542/peds. 2013 -1071 4. Brietzke, S. E. , Shin, J. J. , Choi, S. , Lee, J. T. , Parikh, S. R. , Pena, M. , . . . Rosenfeld, R. M. (2014). Clinical consensus statement: pediatric chronic rhinosinusitis. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg, 151(4), 542 -553. doi: 10. 1177/0194599814549302 5. Hayes, L. L. , Palasis, S. , Bartel, T. B. , Booth, T. N. , Iyer, R. S. , Jones, J. Y. , . . . Karmazyn, B. K. (2018). ACR Appropriateness Criteria Headache-Child. J Am Coll Radiol, 15(5 s), S 78 s 90. doi: 10. 1016/j. jacr. 2018. 03. 017

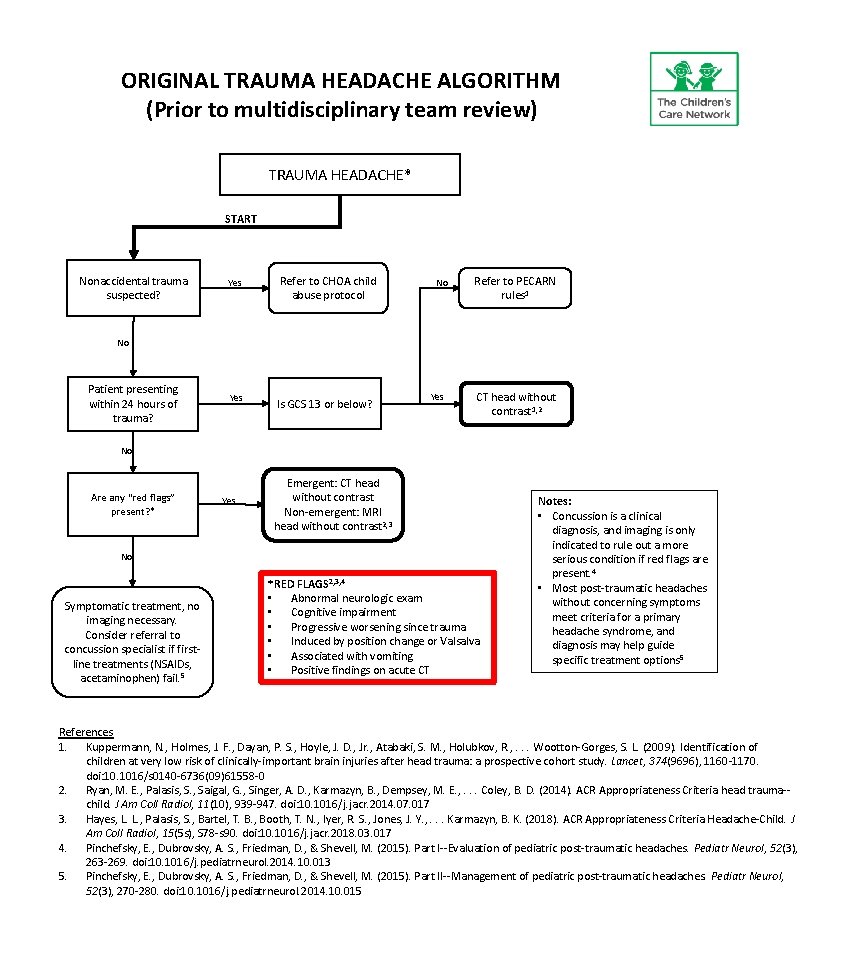

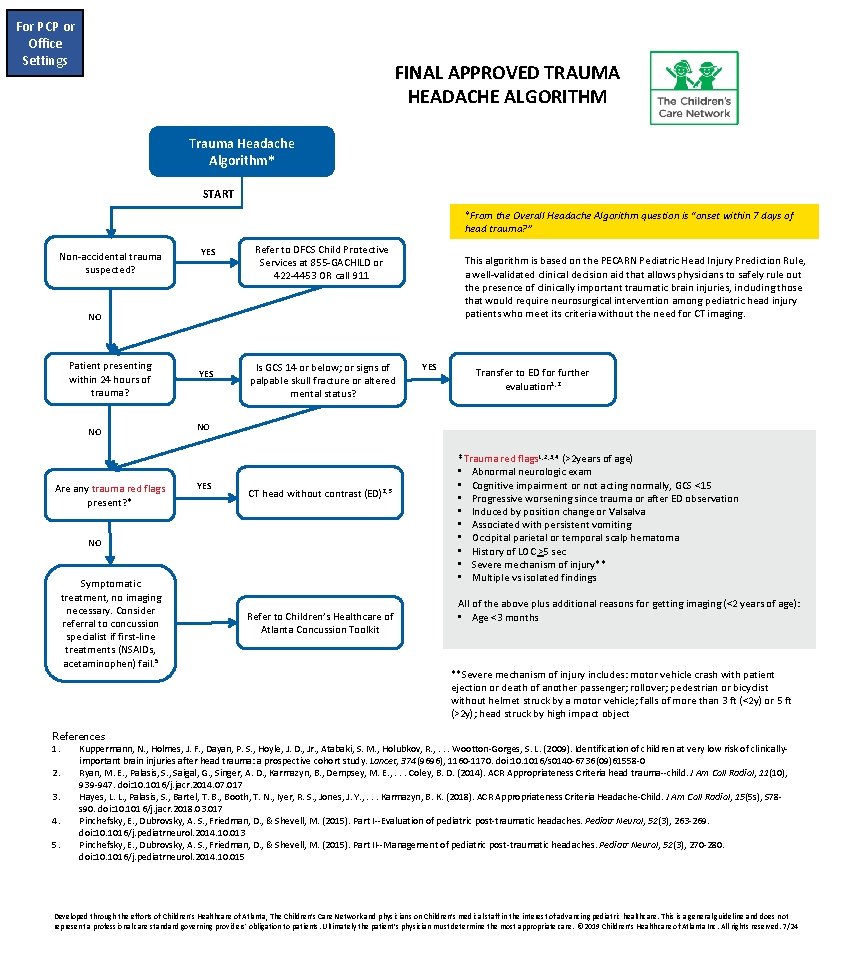

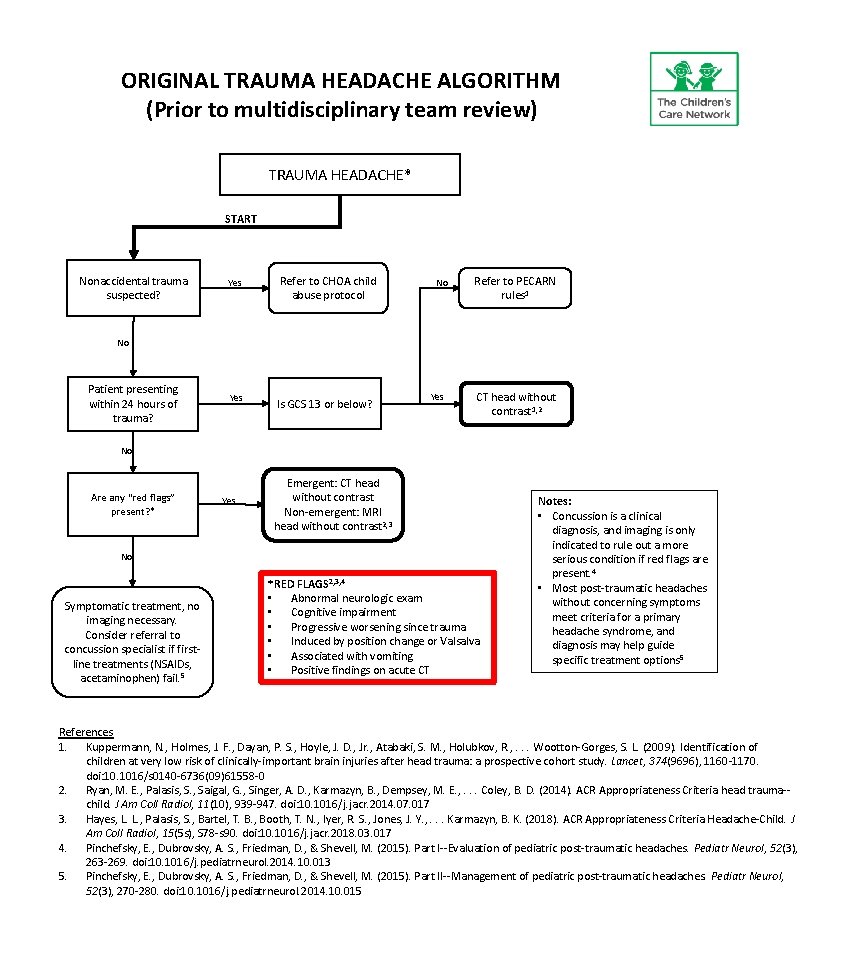

ORIGINAL TRAUMA HEADACHE ALGORITHM (Prior to multidisciplinary team review) TRAUMA HEADACHE* START Nonaccidental trauma suspected? Yes Refer to CHOA child abuse protocol No Refer to PECARN rules 1 No Patient presenting within 24 hours of trauma? Yes Is GCS 13 or below? Yes CT head without contrast 1, 2 No Are any “red flags” present? * Yes Emergent: CT head without contrast Non-emergent: MRI head without contrast 2, 3 No Symptomatic treatment, no imaging necessary. Consider referral to concussion specialist if firstline treatments (NSAIDs, acetaminophen) fail. 5 *RED FLAGS 2, 3, 4 • Abnormal neurologic exam • Cognitive impairment • Progressive worsening since trauma • Induced by position change or Valsalva • Associated with vomiting • Positive findings on acute CT Notes: • Concussion is a clinical diagnosis, and imaging is only indicated to rule out a more serious condition if red flags are present. 4 • Most post-traumatic headaches without concerning symptoms meet criteria for a primary headache syndrome, and diagnosis may help guide specific treatment options 5 References 1. Kuppermann, N. , Holmes, J. F. , Dayan, P. S. , Hoyle, J. D. , Jr. , Atabaki, S. M. , Holubkov, R. , . . . Wootton-Gorges, S. L. (2009). Identification of children at very low risk of clinically-important brain injuries after head trauma: a prospective cohort study. Lancet, 374(9696), 1160 -1170. doi: 10. 1016/s 0140 -6736(09)61558 -0 2. Ryan, M. E. , Palasis, S. , Saigal, G. , Singer, A. D. , Karmazyn, B. , Dempsey, M. E. , . . . Coley, B. D. (2014). ACR Appropriateness Criteria head trauma-child. J Am Coll Radiol, 11(10), 939 -947. doi: 10. 1016/j. jacr. 2014. 07. 017 3. Hayes, L. L. , Palasis, S. , Bartel, T. B. , Booth, T. N. , Iyer, R. S. , Jones, J. Y. , . . . Karmazyn, B. K. (2018). ACR Appropriateness Criteria Headache-Child. J Am Coll Radiol, 15(5 s), S 78 -s 90. doi: 10. 1016/j. jacr. 2018. 03. 017 4. Pinchefsky, E. , Dubrovsky, A. S. , Friedman, D. , & Shevell, M. (2015). Part I--Evaluation of pediatric post-traumatic headaches. Pediatr Neurol, 52(3), 263 -269. doi: 10. 1016/j. pediatrneurol. 2014. 10. 013 5. Pinchefsky, E. , Dubrovsky, A. S. , Friedman, D. , & Shevell, M. (2015). Part II--Management of pediatric post-traumatic headaches. Pediatr Neurol, 52(3), 270 -280. doi: 10. 1016/j. pediatrneurol. 2014. 10. 015

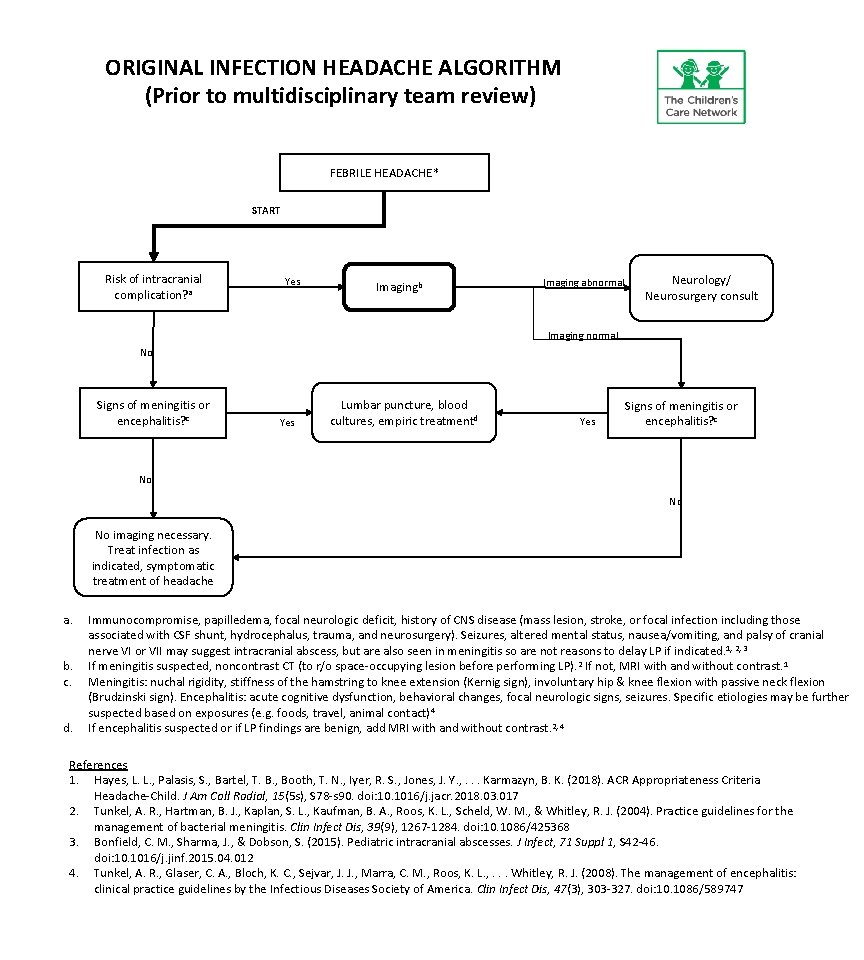

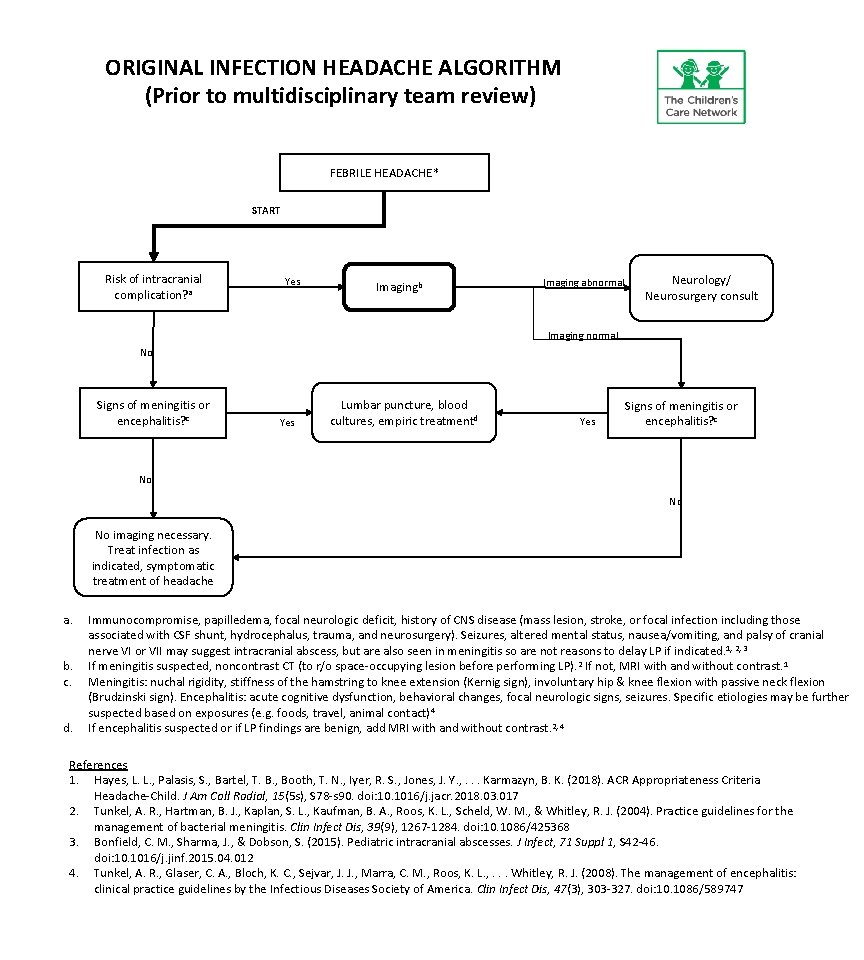

ORIGINAL INFECTION HEADACHE ALGORITHM (Prior to multidisciplinary team review) FEBRILE HEADACHE* START Risk of intracranial complication? a Yes Imagingb Imaging abnormal Neurology/ Neurosurgery consult Imaging normal No Signs of meningitis or encephalitis? c Yes Lumbar puncture, blood cultures, empiric treatmentd Yes Signs of meningitis or encephalitis? c No No No imaging necessary. Treat infection as indicated, symptomatic treatment of headache a. b. c. d. Immunocompromise, papilledema, focal neurologic deficit, history of CNS disease (mass lesion, stroke, or focal infection including those associated with CSF shunt, hydrocephalus, trauma, and neurosurgery). Seizures, altered mental status, nausea/vomiting, and palsy of cranial nerve VI or VII may suggest intracranial abscess, but are also seen in meningitis so are not reasons to delay LP if indicated. 1, 2, 3 If meningitis suspected, noncontrast CT (to r/o space-occupying lesion before performing LP). 2 If not, MRI with and without contrast. 1 Meningitis: nuchal rigidity, stiffness of the hamstring to knee extension (Kernig sign), involuntary hip & knee flexion with passive neck flexion (Brudzinski sign). Encephalitis: acute cognitive dysfunction, behavioral changes, focal neurologic signs, seizures. Specific etiologies may be further suspected based on exposures (e. g. foods, travel, animal contact)4 If encephalitis suspected or if LP findings are benign, add MRI with and without contrast. 2, 4 References 1. Hayes, L. L. , Palasis, S. , Bartel, T. B. , Booth, T. N. , Iyer, R. S. , Jones, J. Y. , . . . Karmazyn, B. K. (2018). ACR Appropriateness Criteria Headache-Child. J Am Coll Radiol, 15(5 s), S 78 -s 90. doi: 10. 1016/j. jacr. 2018. 03. 017 2. Tunkel, A. R. , Hartman, B. J. , Kaplan, S. L. , Kaufman, B. A. , Roos, K. L. , Scheld, W. M. , & Whitley, R. J. (2004). Practice guidelines for the management of bacterial meningitis. Clin Infect Dis, 39(9), 1267 -1284. doi: 10. 1086/425368 3. Bonfield, C. M. , Sharma, J. , & Dobson, S. (2015). Pediatric intracranial abscesses. J Infect, 71 Suppl 1, S 42 -46. doi: 10. 1016/j. jinf. 2015. 04. 012 4. Tunkel, A. R. , Glaser, C. A. , Bloch, K. C. , Sejvar, J. J. , Marra, C. M. , Roos, K. L. , . . . Whitley, R. J. (2008). The management of encephalitis: clinical practice guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis, 47(3), 303 -327. doi: 10. 1086/589747

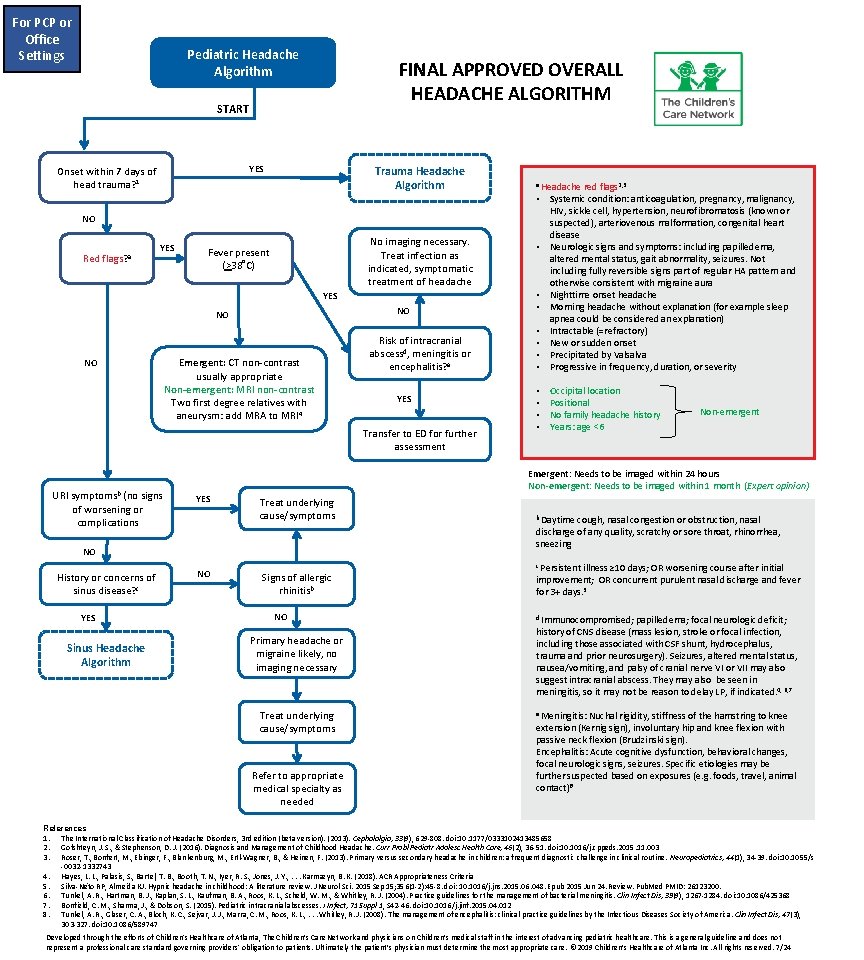

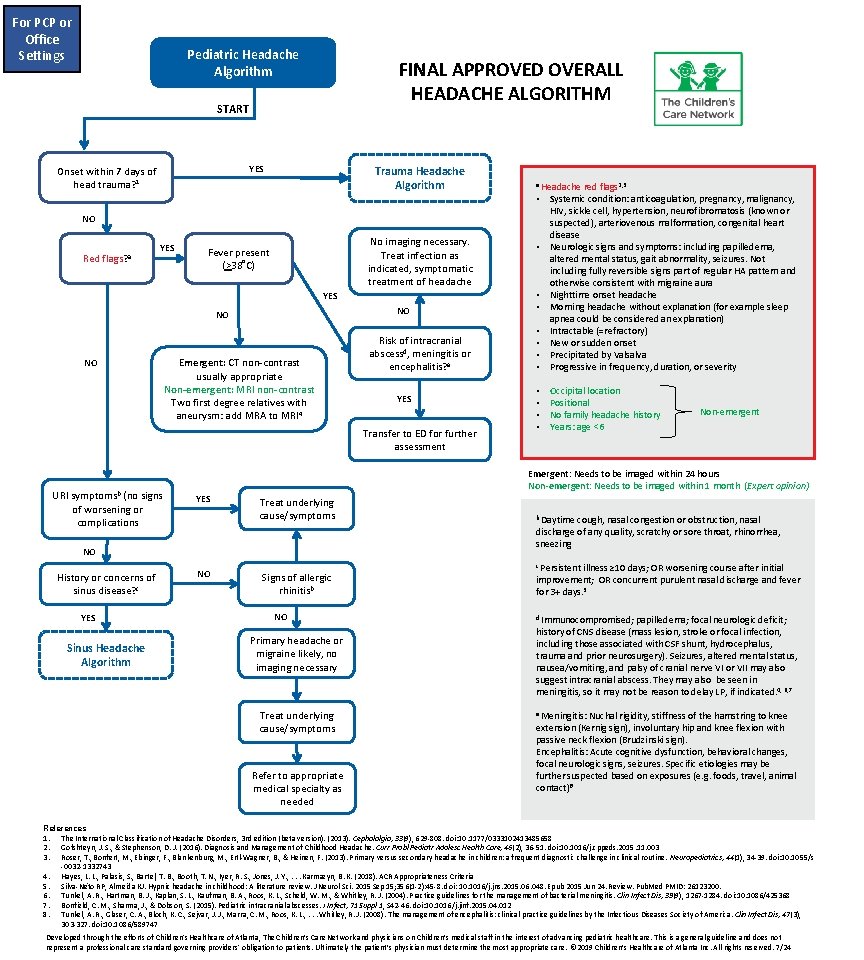

For PCP or Office Settings Pediatric Headache Algorithm FINAL APPROVED OVERALL HEADACHE ALGORITHM START YES Onset within 7 days of head trauma? 1 Trauma Headache Algorithm a Headache • • red flags 2, 3 Systemic condition: anticoagulation, pregnancy, malignancy, HIV, sickle cell, hypertension, neurofibromatosis (known or suspected), arteriovenous malformation, congenital heart disease Neurologic signs and symptoms: including papilledema, altered mental status, gait abnormality, seizures. Not including fully reversible signs part of regular HA pattern and otherwise consistent with migraine aura Nighttime onset headache Morning headache without explanation (for example sleep apnea could be considered an explanation) Intractable (=refractory) New or sudden onset Precipitated by Valsalva Progressive in frequency, duration, or severity • • Occipital location Positional No family headache history Years: age <6 • NO Red flags? a YES No imaging necessary. Treat infection as indicated, symptomatic treatment of headache Fever present (>38˚C) YES NO NO NO Emergent: CT non-contrast usually appropriate Non-emergent: MRI non-contrast Two first degree relatives with aneurysm: add MRA to MRI 4 Risk of intracranial abscessd, meningitis or encephalitis? e YES Transfer to ED for further assessment URI symptomsb (no signs of worsening or complications YES Sinus Headache Algorithm • • Non-emergent Emergent: Needs to be imaged within 24 hours Non-emergent: Needs to be imaged within 1 month (Expert opinion) YES Treat underlying cause/symptoms NO History or concerns of sinus disease? c • NO Signs of allergic rhinitisb NO Primary headache or migraine likely, no imaging necessary Treat underlying cause/symptoms Refer to appropriate medical specialty as needed b Daytime cough, nasal congestion or obstruction, nasal discharge of any quality, scratchy or sore throat, rhinorrhea, sneezing c Persistent illness ≥ 10 days; OR worsening course after initial improvement; OR concurrent purulent nasal discharge and fever for 3+ days. 3 d Immunocompromised; papilledema; focal neurologic deficit; history of CNS disease (mass lesion, stroke or focal infection, including those associated with CSF shunt, hydrocephalus, trauma and prior neurosurgery). Seizures, altered mental status, nausea/vomiting, and palsy of cranial nerve VI or VII may also suggest intracranial abscess. They may also be seen in meningitis, so it may not be reason to delay LP, if indicated. 4, 6, 7 e Meningitis: Nuchal rigidity, stiffness of the hamstring to knee extension (Kernig sign), involuntary hip and knee flexion with passive neck flexion (Brudzinski sign). Encephalitis: Acute cognitive dysfunction, behavioral changes, focal neurologic signs, seizures. Specific etiologies may be further suspected based on exposures (e. g. foods, travel, animal contact)8 References 1. The International Classification of Headache Disorders, 3 rd edition (beta version). (2013). Cephalalgia, 33(9), 629 -808. doi: 10. 1177/0333102413485658 2. Gofshteyn, J. S. , & Stephenson, D. J. (2016). Diagnosis and Management of Childhood Headache. Curr Probl Pediatr Adolesc Health Care, 46(2), 36 -51. doi: 10. 1016/j. cppeds. 2015. 11. 003 3. Roser, T. , Bonfert, M. , Ebinger, F. , Blankenburg, M. , Ertl-Wagner, B. , & Heinen, F. (2013). Primary versus secondary headache in children: a frequent diagnostic challenge in clinical routine. Neuropediatrics, 44(1), 34 -39. doi: 10. 1055/s -0032 -1332743 4. Hayes, L. L. , Palasis, S. , Bartel, T. B. , Booth, T. N. , Iyer, R. S. , Jones, J. Y. , . . . Karmazyn, B. K. (2018). ACR Appropriateness Criteria 5. Silva-Néto RP, Almeida KJ. Hypnic headache in childhood: A literature review. J Neurol Sci. 2015 Sep 15; 356(1 -2): 45 -8. doi: 10. 1016/j. jns. 2015. 06. 048. Epub 2015 Jun 24. Review. Pub. Med PMID: 26123200. 6. Tunkel, A. R. , Hartman, B. J. , Kaplan, S. L. , Kaufman, B. A. , Roos, K. L. , Scheld, W. M. , & Whitley, R. J. (2004). Practice guidelines for the management of bacterial meningitis. Clin Infect Dis, 39(9), 1267 -1284. doi: 10. 1086/425368 7. Bonfield, C. M. , Sharma, J. , & Dobson, S. (2015). Pediatric intracranial abscesses. J Infect, 71 Suppl 1, S 42 -46. doi: 10. 1016/j. jinf. 2015. 04. 012 8. Tunkel, A. R. , Glaser, C. A. , Bloch, K. C. , Sejvar, J. J. , Marra, C. M. , Roos, K. L. , . . . Whitley, R. J. (2008). The management of encephalitis: clinical practice guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis, 47(3), 303 -327. doi: 10. 1086/589747 Developed through the efforts of Children's Healthcare of Atlanta, The Children’s Care Network and physicians on Children’s medical staff in the interest of advancing pediatric healthcare. This is a general guideline and does not represent a professional care standard governing providers' obligation to patients. Ultimately the patient’s physician must determine the most appropriate care. © 2019 Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta Inc. All rights reserved. 7/24

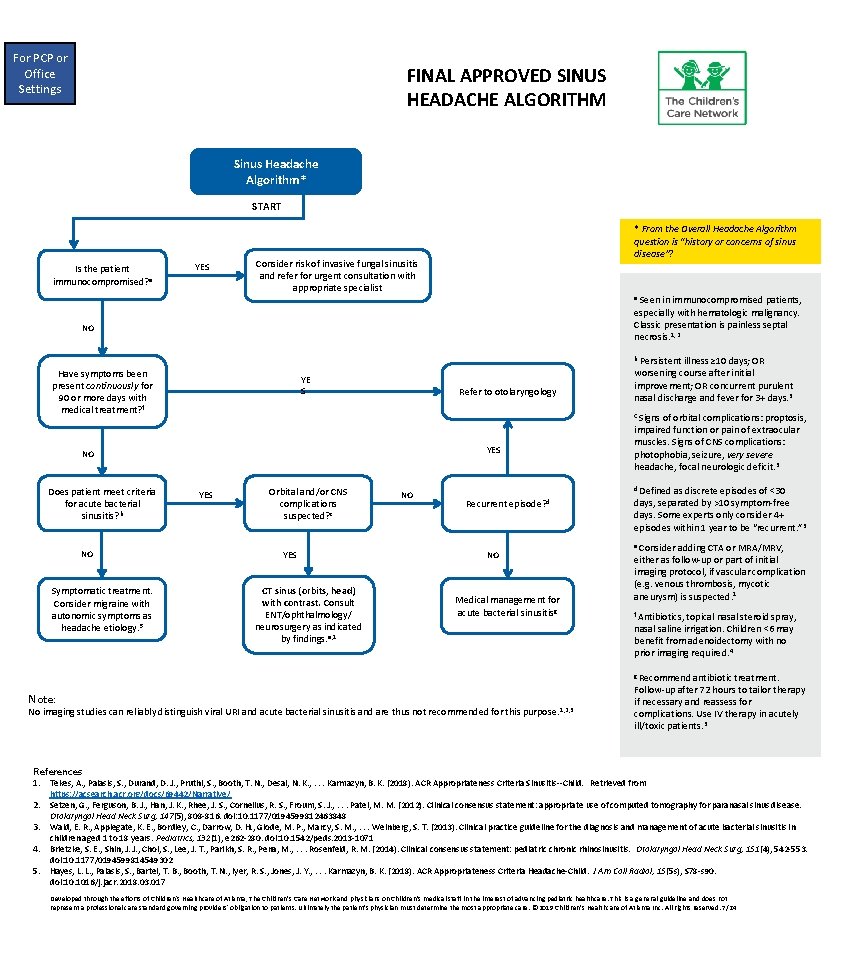

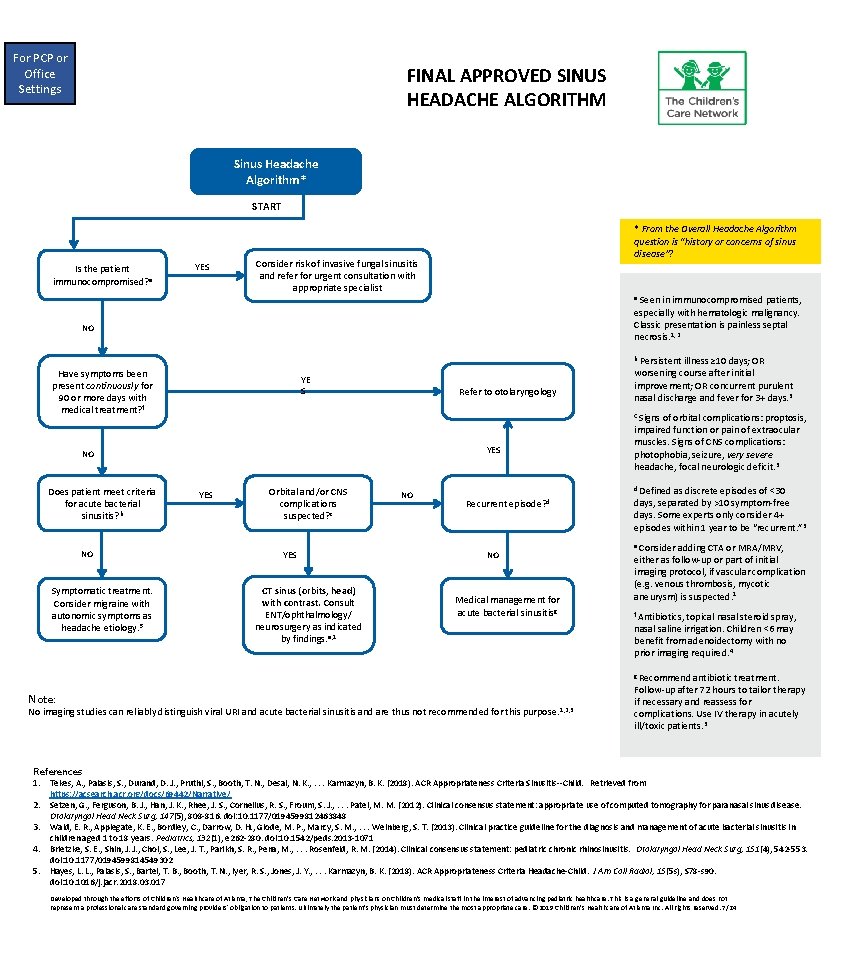

For PCP or Office Settings FINAL APPROVED SINUS HEADACHE ALGORITHM Sinus Headache Algorithm* START Is the patient immunocompromised? a YES * From the Overall Headache Algorithm question is “history or concerns of sinus disease”? Consider risk of invasive fungal sinusitis and refer for urgent consultation with appropriate specialist Seen in immunocompromised patients, especially with hematologic malignancy. Classic presentation is painless septal necrosis. 1, 2 a NO Persistent illness ≥ 10 days; OR worsening course after initial improvement; OR concurrent purulent nasal discharge and fever for 3+ days. 3 b Have symptoms been present continuously for 90 or more days with medical treatment? f YE S Refer to otolaryngology C Signs YES NO Does patient meet criteria for acute bacterial sinusitis? b NO Symptomatic treatment. Consider migraine with autonomic symptoms as headache etiology. 5 of orbital complications: proptosis, impaired function or pain of extraocular muscles. Signs of CNS complications: photophobia, seizure, very severe headache, focal neurologic deficit. 3 YES Orbital and/or CNS complications suspected? c YES CT sinus (orbits, head) with contrast. Consult ENT/ophthalmology/ neurosurgery as indicated by findings. e, 1 NO d Defined Recurrent episode? d NO Medical management for acute bacterial sinusitisg as discrete episodes of <30 days, separated by >10 symptom-free days. Some experts only consider 4+ episodes within 1 year to be “recurrent. ” 3 e Consider adding CTA or MRA/MRV, either as follow-up or part of initial imaging protocol, if vascular complication (e. g. venous thrombosis, mycotic aneurysm) is suspected. 1 f Antibiotics, topical nasal steroid spray, nasal saline irrigation. Children <6 may benefit from adenoidectomy with no prior imaging required. 4 g Recommend Note: No imaging studies can reliably distinguish viral URI and acute bacterial sinusitis and are thus not recommended for this purpose. 1, 2, 3 antibiotic treatment. Follow-up after 72 hours to tailor therapy if necessary and reassess for complications. Use IV therapy in acutely ill/toxic patients. 3 References 1. Tekes, A. , Palasis, S. , Durand, D. J. , Pruthi, S. , Booth, T. N. , Desai, N. K. , . . . Karmazyn, B. K. (2018). ACR Appropriateness Criteria Sinusitis--Child. Retrieved from https: //acsearch. acr. org/docs/69442/Narrative/ 2. Setzen, G. , Ferguson, B. J. , Han, J. K. , Rhee, J. S. , Cornelius, R. S. , Froum, S. J. , . . . Patel, M. M. (2012). Clinical consensus statement: appropriate use of computed tomography for paranasal sinus disease. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg, 147(5), 808 -816. doi: 10. 1177/0194599812463848 3. Wald, E. R. , Applegate, K. E. , Bordley, C. , Darrow, D. H. , Glode, M. P. , Marcy, S. M. , . . . Weinberg, S. T. (2013). Clinical practice guideline for the diagnosis and management of acute bacterial sinusitis in children aged 1 to 18 years. Pediatrics, 132(1), e 262 -280. doi: 10. 1542/peds. 2013 -1071 4. Brietzke, S. E. , Shin, J. J. , Choi, S. , Lee, J. T. , Parikh, S. R. , Pena, M. , . . . Rosenfeld, R. M. (2014). Clinical consensus statement: pediatric chronic rhinosinusitis. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg, 151(4), 542 -553. doi: 10. 1177/0194599814549302 5. Hayes, L. L. , Palasis, S. , Bartel, T. B. , Booth, T. N. , Iyer, R. S. , Jones, J. Y. , . . . Karmazyn, B. K. (2018). ACR Appropriateness Criteria Headache-Child. J Am Coll Radiol, 15(5 s), S 78 -s 90. doi: 10. 1016/j. jacr. 2018. 03. 017 Developed through the efforts of Children's Healthcare of Atlanta, The Children’s Care Network and physicians on Children’s medical staff in the interest of advancing pediatric healthcare. This is a general guideline and does not represent a professional care standard governing providers' obligation to patients. Ultimately the patient’s physician must determine the most appropriate care. © 2019 Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta Inc. All rights reserved. 7/24

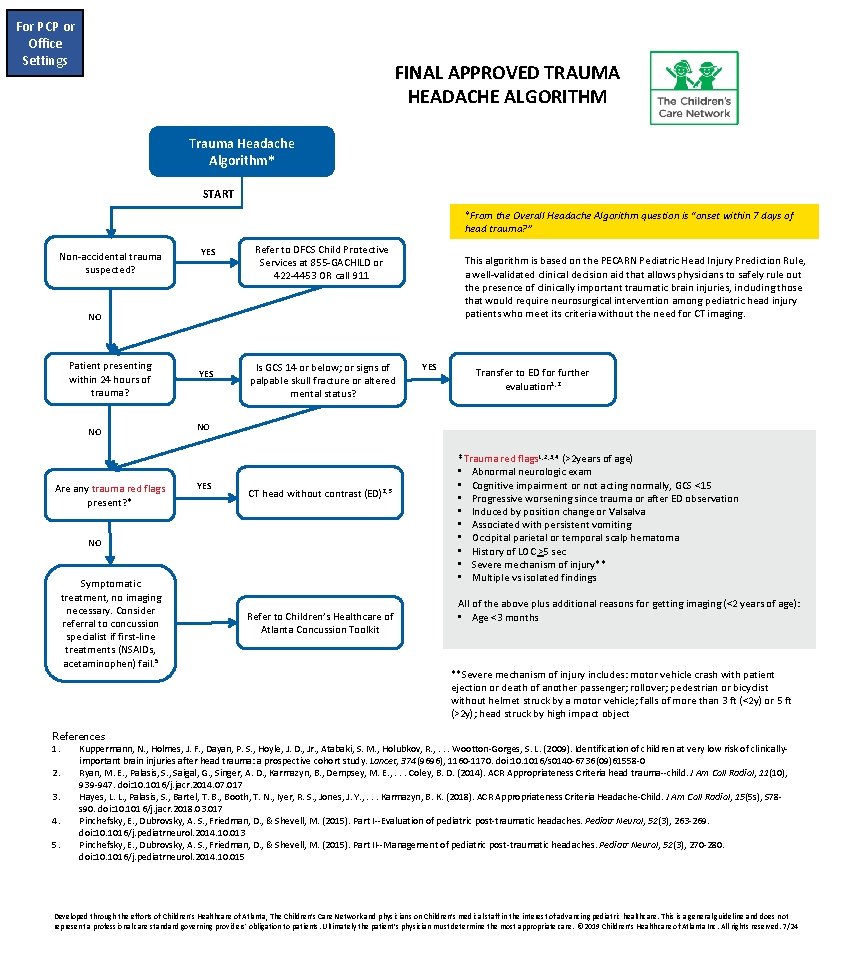

For PCP or Office Settings FINAL APPROVED TRAUMA HEADACHE ALGORITHM Trauma Headache Algorithm* START *From the Overall Headache Algorithm question is “onset within 7 days of head trauma? ” Non-accidental trauma suspected? YES Refer to DFCS Child Protective Services at 855 -GACHILD or 422 -4453 OR call 911 This algorithm is based on the PECARN Pediatric Head Injury Prediction Rule, a well-validated clinical decision aid that allows physicians to safely rule out the presence of clinically important traumatic brain injuries, including those that would require neurosurgical intervention among pediatric head injury patients who meet its criteria without the need for CT imaging. NO Patient presenting within 24 hours of trauma? NO Are any trauma red flags present? * YES Is GCS 14 or below; or signs of palpable skull fracture or altered mental status? Transfer to ED for further evaluation 1, 2 NO YES CT head without contrast (ED)2, 3 NO Symptomatic treatment, no imaging necessary. Consider referral to concussion specialist if first-line treatments (NSAIDs, acetaminophen) fail. 5 YES Refer to Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta Concussion Toolkit *Trauma red flags 1, 2, 3, 4 (>2 years of age) • Abnormal neurologic exam • Cognitive impairment or not acting normally, GCS <15 • Progressive worsening since trauma or after ED observation • Induced by position change or Valsalva • Associated with persistent vomiting • Occipital parietal or temporal scalp hematoma • History of LOC >5 sec • Severe mechanism of injury** • Multiple vs isolated findings All of the above plus additional reasons for getting imaging (<2 years of age): • Age <3 months **Severe mechanism of injury includes: motor vehicle crash with patient ejection or death of another passenger; rollover; pedestrian or bicyclist without helmet struck by a motor vehicle; falls of more than 3 ft (<2 y) or 5 ft (>2 y); head struck by high impact object References 1. Kuppermann, N. , Holmes, J. F. , Dayan, P. S. , Hoyle, J. D. , Jr. , Atabaki, S. M. , Holubkov, R. , . . . Wootton-Gorges, S. L. (2009). Identification of children at very low risk of clinicallyimportant brain injuries after head trauma: a prospective cohort study. Lancet, 374(9696), 1160 -1170. doi: 10. 1016/s 0140 -6736(09)61558 -0 2. Ryan, M. E. , Palasis, S. , Saigal, G. , Singer, A. D. , Karmazyn, B. , Dempsey, M. E. , . . . Coley, B. D. (2014). ACR Appropriateness Criteria head trauma--child. J Am Coll Radiol, 11(10), 939 -947. doi: 10. 1016/j. jacr. 2014. 07. 017 3. Hayes, L. L. , Palasis, S. , Bartel, T. B. , Booth, T. N. , Iyer, R. S. , Jones, J. Y. , . . . Karmazyn, B. K. (2018). ACR Appropriateness Criteria Headache-Child. J Am Coll Radiol, 15(5 s), S 78 s 90. doi: 10. 1016/j. jacr. 2018. 03. 017 4. Pinchefsky, E. , Dubrovsky, A. S. , Friedman, D. , & Shevell, M. (2015). Part I--Evaluation of pediatric post-traumatic headaches. Pediatr Neurol, 52(3), 263 -269. doi: 10. 1016/j. pediatrneurol. 2014. 10. 013 5. Pinchefsky, E. , Dubrovsky, A. S. , Friedman, D. , & Shevell, M. (2015). Part II--Management of pediatric post-traumatic headaches. Pediatr Neurol, 52(3), 270 -280. doi: 10. 1016/j. pediatrneurol. 2014. 10. 015 Developed through the efforts of Children's Healthcare of Atlanta, The Children’s Care Network and physicians on Children’s medical staff in the interest of advancing pediatric healthcare. This is a general guideline and does not represent a professional care standard governing providers' obligation to patients. Ultimately the patient’s physician must determine the most appropriate care. © 2019 Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta Inc. All rights reserved. 7/24