II Confessional Natural Theology and Interdenominational Natural Religion

- Slides: 36

II. Confessional Natural Theology and Interdenominational Natural Religion • • Natural Theology Natural knowledge of God Theism Confessional • • Natural Religion Natural relation to God Deism Interdenominational

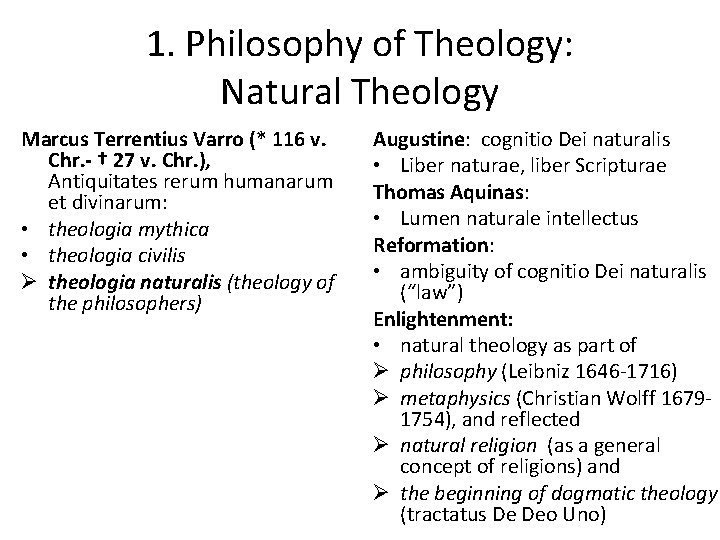

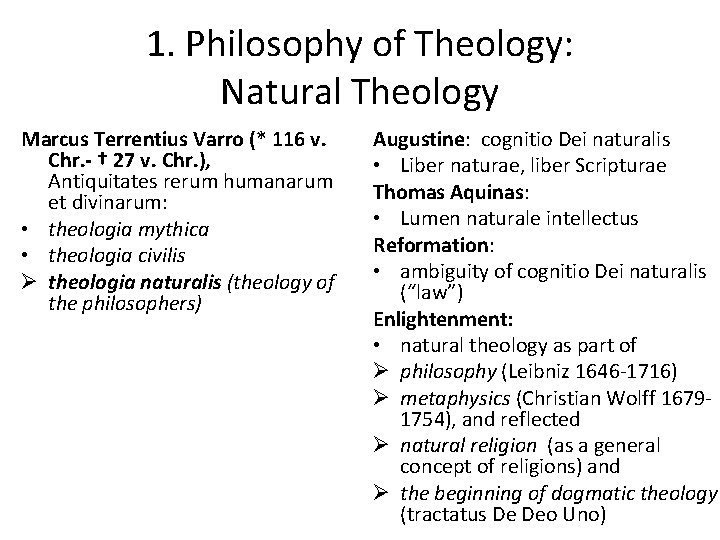

1. Philosophy of Theology: Natural Theology Marcus Terrentius Varro (* 116 v. Chr. - † 27 v. Chr. ), Antiquitates rerum humanarum et divinarum: • theologia mythica • theologia civilis Ø theologia naturalis (theology of the philosophers) Augustine: cognitio Dei naturalis • Liber naturae, liber Scripturae Thomas Aquinas: • Lumen naturale intellectus Reformation: • ambiguity of cognitio Dei naturalis (“law”) Enlightenment: • natural theology as part of Ø philosophy (Leibniz 1646 -1716) Ø metaphysics (Christian Wolff 16791754), and reflected Ø natural religion (as a general concept of religions) and Ø the beginning of dogmatic theology (tractatus De Deo Uno)

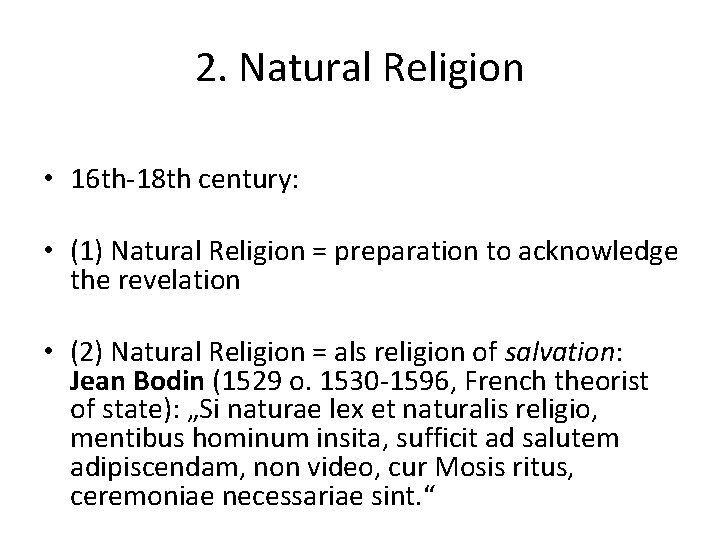

2. Natural Religion • 16 th-18 th century: • (1) Natural Religion = preparation to acknowledge the revelation • (2) Natural Religion = als religion of salvation: Jean Bodin (1529 o. 1530 -1596, French theorist of state): „Si naturae lex et naturalis religio, mentibus hominum insita, sufficit ad salutem adipiscendam, non video, cur Mosis ritus, ceremoniae necessariae sint. “

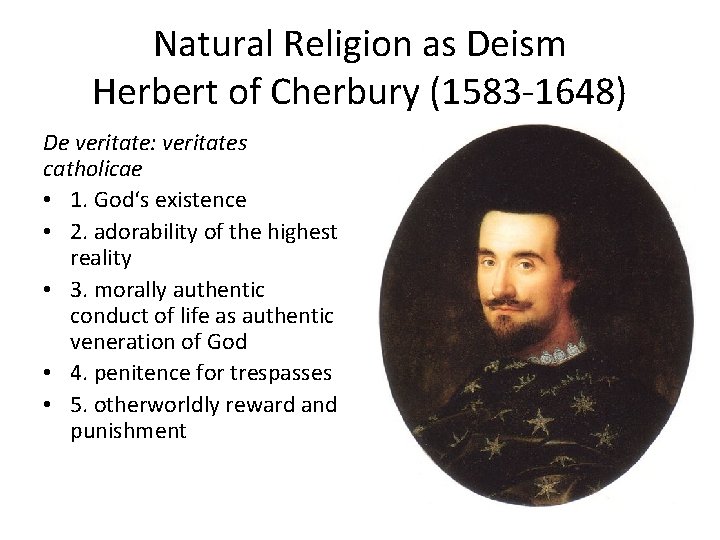

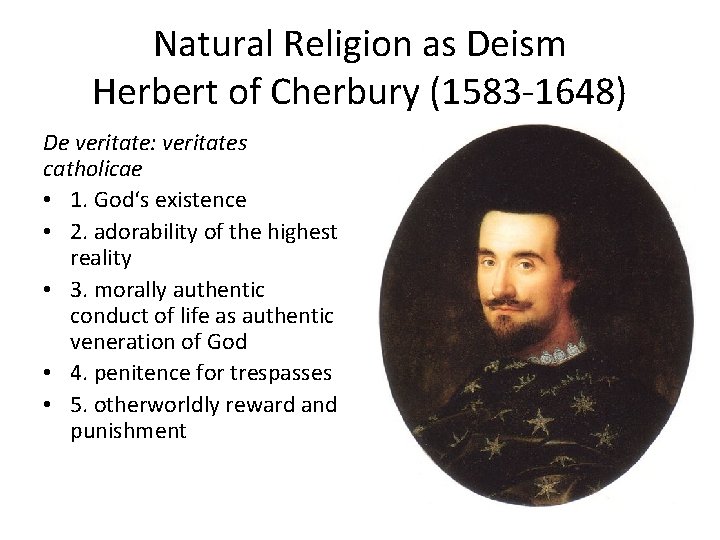

Natural Religion as Deism Herbert of Cherbury (1583 -1648) De veritate: veritates catholicae • 1. God‘s existence • 2. adorability of the highest reality • 3. morally authentic conduct of life as authentic veneration of God • 4. penitence for trespasses • 5. otherworldly reward and punishment

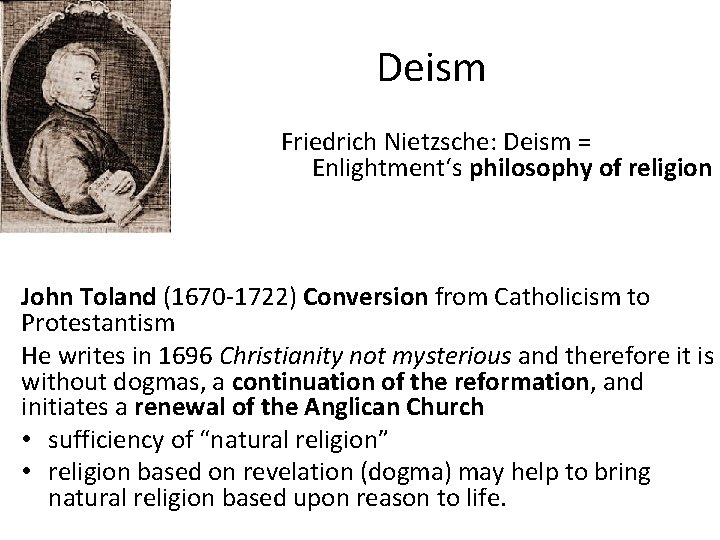

Deism Friedrich Nietzsche: Deism = Enlightment‘s philosophy of religion John Toland (1670 -1722) Conversion from Catholicism to Protestantism He writes in 1696 Christianity not mysterious and therefore it is without dogmas, a continuation of the reformation, and initiates a renewal of the Anglican Church • sufficiency of “natural religion” • religion based on revelation (dogma) may help to bring natural religion based upon reason to life.

Interdenominational Deism • Matthew Tindal (1657 -1733) Christianity as old as the Creation, or the Gospel a Republication of the Religion of Nature (1730). „Bible of Deism“. • He changed from Anglicanism to Catholicism and returned to Anglicanism

Interreligious philosophy: The problem of historical truth Gotthold Ephraim Lessing (1729 -1781) • 1777 tract On the Proof of the Spirit and of Power: “That, then, is the ugly great ditch which I cannot cross, however often and however earnestly I have tried to make that leap. " “Accidental truths of history can never become the proof of necessary truths of reason. ”

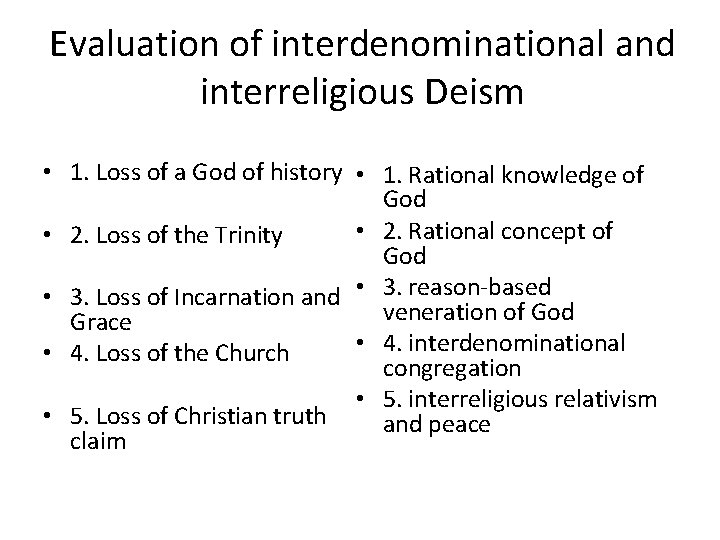

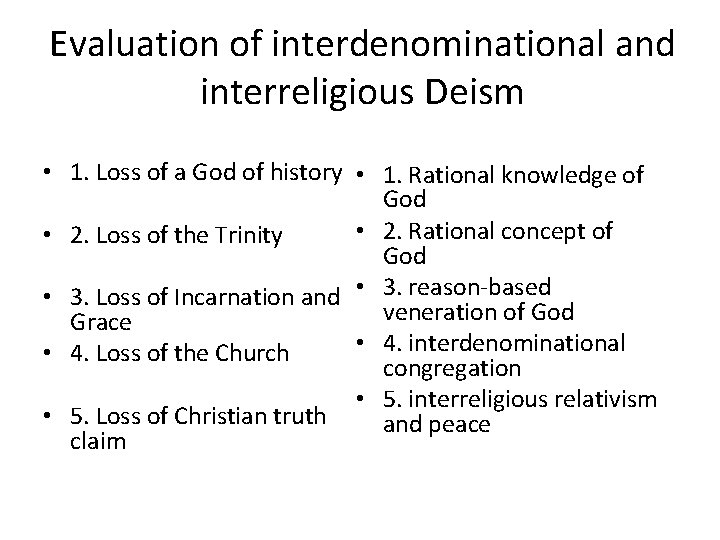

Evaluation of interdenominational and interreligious Deism • 1. Loss of a God of history • 1. Rational knowledge of God • 2. Rational concept of • 2. Loss of the Trinity God • 3. Loss of Incarnation and • 3. reason-based veneration of God Grace • 4. interdenominational • 4. Loss of the Church congregation • 5. interreligious relativism • 5. Loss of Christian truth and peace claim

3. The Critique of Natural Theology and Natural Religion • David Hume • Immanuel Kant • Johann Georg Hermann

David Hume (1711 -1776) ‘s critique of natural religion and natural theology The Natural History of Religion (1755): • priority of ploytheism (against Tindal: monotheism not so old as creation) Motivation of monotheism is not reason, but passion, ambition and flattery such as servile courtiers pay to princes. Thus a specific deity like the God of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob was finally elevated to be the only God. • • Tolerance of polytheism, intolerance of monotheism Monotheistic position are not more rational as polytheistic assumptions • Dialogues Concerning Natural Religion (1779) • Cleanthes: exponent of natural religion: teleological argument, evidence of design in the universe • Philo: attacks Cleanthes' natural religion , its anthropomorphism and teleology • human reason is inadequate to make any assumptions about the divine Ens necessarium could be the world as well; we do not know all its characterisctis Demea: Cosmological argument, theism, critique of Cleanthes' "natural religion“: too anthropomorphic. • •

Theological Critique (Protestant) Johann Georg Hamann (1730 -1788) • In 1780 he reads the dialogues and supports them in order to prove that Christianity cannot be reduced to Natural Religion. • Hamann claims that “faith” and not rational grounds underlies his contemporaries' high valuation of reason. It is not an impartial “reason” which criticizes “blind faith”, but another faith / conviction. •

Philosophical Critique of Natural Religion and Natural Theology and the beginning of a philosophy of religion: Immanuel Kant • Hamann sent his translation of Hume‘s Dialogues to Kant, while Kant was writing the Critique of the Pure Reason. • Consequences: Ø Impossibility of a physicotheological proof Ø Accepts Hume‘s critique of theistic anthropomorphism Ø Kant’s refuses Natural Religion because of its metaphysical form, but develops a philosophy of religion

III. I. Kant‘s philosophy of religion • Philosophy of religion does not substitute the middle-aged harmony of faith and knowledge, it is the point of intersection: critical self-controlled thinking and religious, theological thought. • This self-controlled thinking negatively means: 1) critique of rational theology it effects positively: 2) Restitution of a postulated idea of God by practical (moral) philosophy 3) Philosophy of religion on the base of this restituted idea of God (no reduction of phil. of rel. to a mere analysis of religious practice)

1. Critique of rational (natural) theology • Decline of the ontological and metaphysical conditions of the proves of God‘s existence: Being is no longer an ontological principle: the universal act constitutes the existence of contingent essence and permits to ask for the origin of this act in an actus purus. Being is the empirical position of an essentially defined thing, no part of essence, no perfection of reality: therefore neither the essence of God nor the idea of an ens perfectissimum includes existence. Kr. V: God as the ideal of reason (wise person): the subject of all realities (omnitudo realitatis – wisdom) {Why to pass from idea to ideal = from the omnitudo realitatis to an absolute subject of this realities but excluding all realities which are opposed to others and those which are incompatible with God? }

2. Restitution of a postulated idea of God by practical (moral) philosophy • “a postulate of pure practical reason by which I mean a theoretical proposition, not demonstrable as such, but which is an inseparable result of an unconditional a priori practical law. ” • Theoretical: affirmation, no moral obligation • Not demonstrable: not based on knowledge • Connected with practical moral law • This practical moral law = intelligible (no empirical) factum of the reason = categorical imperative

The postulates of moral law • 1. freedom: moral law is directed to freedom • 2. The law requires its realization which is not attainable in actuality, but must be attainable sometime in future → immortality of soul • 3. not as a motif of acting, but as its effect, the unconditional valid moral law requires unlimited (unconditional) happiness which presupposes God as the power which guarantees happiness in correspondence to virtue, the highest good is the unity of happiness, blissfulness (Glückseligkeit) and virtue (Glückswürdigkeit – merit happiness).

3. Philosophy of religion on the base of the restituted idea of God • Like Toland, Tindal, Lessing and others, Kant bases religion on reason and its moral law: the moral law requires the postulate of God; therefore moral law can be considered as God‘s commandment. But moral obligation does not originate in God, it comes from autonomous reason. • Religious actions (prayer, liturgy…) have to remember the moral duty, they do neither achieve anything from God nor compensate failed moral actions. • There are no excuses for moral failure: moral duty proves human capacity to act morally : We ought, so we can! • Radical evil (original sin) is based on personal decision to choose sensuality instead of morality as maxim of acting • The moral interprets Bible. • Natural, reason-based-religion remains open for “taught” religion (religion of revelation)

„Die Religion innerhalb der Grenzen der bloßen Vernunft A XVf. “: Vorrede zur 1. Aufl. 1793 • „Es steht aber der biblischen Theologie im Felde der Wissenschaften eine philosophische Theologie gegenüber, die das anvertraute Gut einer andern Fakultät ist. Diese, wenn sie nur innerhalb der Grenzen der bloßen Vernunft bleibt, und zur Bestätigung und Erläuterung ihrer Sätze die Geschichte, Sprachen, Bücher aller Völker, selbst die Bibel benutzt, aber nur für sich, ohne diese Sätze in die biblische Theologie hineinzutragen, und dieser ihre öffentlichen Lehren, dafür der Geistliche privilegiert ist, abändern zu wollen, muß volle Freiheit haben, sich, so weit, als ihre Wissenschaft reicht, auszubreiten; und obgleich, wenn ausgemacht ist, daß der erste wirklich seine Grenze überschritten, und in die biblische Theologie Eingriffe getan habe, dem Theologen (bloß als Geistlichen betrachtet) das Recht der Zensur nicht bestritten werden kann, so kann doch, sobald jenes noch bezweifelt wird, und also die Frage eintritt: ob jenes durch eine Schrift, oder einen andern öffentlichen Vortrag des Philosophen geschehen sei, nur dem biblischen Theologen, als Gliede seiner Fakultät, die Oberzensur zustehen, weil dieser auch das zweite Interesse des gemeinen Wesens, nämlich den Flor der Wissenschaften zu besorgen angewiesen, und eben so gültig als der erstere angestellt worden ist. …“

“Religion within the Limits of Reason Alone” prologue 1. ed. • “Among the sciences, however, there is, over and against Biblical theology, a philosophical theology, which is an estate entrusted to another faculty. So long as this philosophical theology remains within the limits of reason alone, and for the confirmation and exposition of its propositions makes use of history, sayings, books of all peoples, even the Bible, but only for itself, without wishing to carry these propositions into Biblical theology or to change the latter’s public doctrines – a privilege of divines – it must have complete freedom to expand as far as its science reaches. ” (A XVs. )

4. Philosophical Questions concerning Kant’s Philosophy of Religion • → scientific reason and religion as opposed human activities, irrationality of religion. • 1790: the moral argument loses its persuasiveness: 1. The danger of eternal bliss as a motif of action 2. Why does God create a world in which it is necessary for the righteous to suffer, so that God’s world needs a eternal compensation? 3. Are there additional human capacities than the limited reason to get to God?

5. Protestant and Catholic Kantians Heinrich Philipp Konrad Henke (1752 -1809), Lutheran Theologian • Concrete religions convert in moral religion of reason (cf. Lessing). • Change from a Religion of Christ (“Christolatrism”) to Christ‘s Religion: the religion that Jesus had. No “Biblelatrism” (Inspiration), no “Onomatolatrism” (ὄνομα) = unclear and confusing dogmatic definitions like the Trinity or the doctrine of two different natures in Christ. Jesus is the morally perfect man teaching virtues and knowledge of God. This teaching is necessary because of personal sins which first example is Adam‘s sin (no original sin). • Acting morally, one becomes an imagine of God (it is not a gift by creation, we have to earn it).

Protestant and Catholic Kantians Johann Heinrich Tieftrunk (1759 -1837), Protestant Philosopher of Religion • Reason decides about revelation‘s content • Revelation is necessary because of human being‘s morally decadent condition; revelation serves exclusively to wake up human consciousness. • Christ is the teacher of morality.

5. Protestant and Catholic Kantians Sebastian Mutschelle (1749 -1800) Roman-Cath. Theologian • Reason as the source of the moral. Wrong: God wants something, therefore it is good. Right: Something is good; therefore God wants it. • Symmetry of charity and self-love (Selbstliebe) • To love God = to follow the commandments • Augustinus: De magistro = Vernunft

Protestant and Catholic Kantians Matern Reuß (1751 -1798) (Würzburger Benedictine) • Examination of cognitive capacities in order to avoid unproven metaphysics. • Theoretical reason leads to a positive stalemate between the proofs for God and proofs for atheism, materialism. • Practical reason: postulates of freedom, soul, God.

Protestant and Catholic Kantians Ildephons Schwarz (1752 -1794) Benedictine Handbuch der christlichen Religion 1793/94 • Positive deadlock of pro and con theoretical proofs of God and God’s non-existence… = against materialism. • Acceptance of Kant’s moral foundation of theology. • Revelation facilitates the realization of morality. • Kant against Luther: grace is the revolution of one’s way of thinking, not a simple pardon, nor a pure imputation.

6. Evaluation of a theology within Kant‘s philosophy of religion No theoretical knowledge of God. Postulates of God‘s reality. Moral formatting of religion. Reason as criteria of religious belief. Revelation is nothing but motivation, teaching: Christ the ideal and teacher of morals and virtues. • Critique of central Christian Truths (Trinity). • Protestant Kantians accept and receive Kant’s approach more than Catholic ones. • • •

7. Protestant Character of Kant‘s philosophy of religion? Friedrich Paulsen (1846 -1908) Philosopher, Pedagogue • Immanuel Kant. Sein Leben und seine Lehre (1898); Kant - der Philosoph des Protestantismus (1899). • Kant‘s understanding of religion 1) as something „antiintellectual“, 2) as a religion of conscience, morality • Kant‘s concept of a practical • Anti-intellectualism: Kant‘s critique faith of reason corresponds blocks a dogmatic rationalism which to Luther‘s concept of Paulsen identifies with Cath. Theology (Neothomism). religion as pertaining to one’s inner conviction.

Protestant Character of Kant‘s philosophy of religion? Julius Kaftan (1848 -1926), Protestant Theologian • Kant‘s concept of morality corresponds to Protestantism and distinguishes from Cath. and Orthodoxy. • The internal experience of morality leads to God and not the cognition of the external world (= cf. five ways to God in Thomas Aquinas’ Summa Theologiae which start with external worldexperience: movement, causality…. ).

Protestant Character of Kant‘s philosophy of religion? Bruno Bauch (1877 -1942) philosopher, Neokantianism Kant and Luther coincide in the idea of ethics of conviction (Gesinnungsethik); therefore both put the focus on tow things: • 1) subjectivity and • 2) morality as the decisive factor in relation to God

Alexander Heit (* 1969) Theologian, Basel Versöhnte Vernunft. Eine Studie zur systematischen Bedeutung des Rechtfertigungsgedankens für Kants Religionsphilosophie (2006) • Congruence of Kant and Luther in the doctrine of justification. • Kant articulates the difference between concrete human being and moral duty (Sollen): faith in justification is the answer to this difference in conformity to reason (149).

Protestant Character of Kant‘s philosophy of religion? • Since Kant requires the personal appropriation and individual realization of justification through the maxim of acting (Sittlichkeit / morality above Sinnlichkeit / sensuality), Heit claims that Kant‘s position is closer to Luther than to Melanchthon. While Luther underlines the human existence determinating effect of faith and a principle of appropriation concerning grace, Melanchthon develops a mere forensic concept of justification (persistence of sinfulness, unrighteousness, unregeneracy) which was received as the official doctrine in the Formula Concordiae (Konkordienformel) of 1577. Heit quotes Luther-Interpretations which affirm Luther‘s idea of appropriation → exclusively this interpretation proves the claimed nearness of Luther and Kant, and thesis that Kant is the philosopher of Protestantism. Cf. Andreas Osiander (1498 -1552): justification becomes a real part of the person; God‘s Word is present in the justified.

8. A Catholic Kant? • Kant‘s critique of sola fide, sola gratia, sola scriptura: he insists on reason’s leading role → Walter Schultz, Kant als Philosoph des Protestantismus (1960): that is really the question, if he is it. • Kant: Catholics are more consequential, he praises enlightened Catholics: accepted importance of reason and responsible actions.

What does Kant tell us about his confessional standpoint? Aloysius Winter, Kant zwischen den Konfessionen, in: idem, Der andere Kant. Zur philosophischen Theologie Immanuel Kants, Hildesheim 2000, 1 -47: • Kant keeps an equidistance to the confessions which he calls religious parties, sects. • Crucial: the religion of reason; confessional attributes are scriptures (Bible, Koran), dogmas (Trinity), churchconstitutions, rituals (liturgy, devotions), costumes… they are not essential; positively, they can help to mediate and grasp better the religion of reason.

Kant‘s Experience • 1732 Collegium Fridericianum • Slavery: devotions, services, discipline • Preparation to receive the Last Supper took 4 weeks, including a written confession concerning the state of mind; no separation of forum internum and externum.

9. Kant – Philosopher of Ecumenism? A. Winter, Kant zwischen den Konfessionen, 47: Kant’s philosophy claims for • Self-critique • pure conviction • rational argument • against: dogmatism and skepticism • search for natural and philosophical base of religion

10. Results Kant‘s moral philosophy of religion as a point of reference for: • Protestant • Catholic • ecumenical and interdenominational approaches • even for interreligious approaches Problematic and perspective: • Moralistic reduction of religion • Revelation as admonition and teaching, not a event, history, relation between God an mankind. • Against this tendency may help Kant‘s emphazis on freedom: in order to conceive revelation as an event of God‘s and humans freedom. • Reduction of the dialogic nature of human and divine being.

Theology of glory vs theology of the cross

Theology of glory vs theology of the cross Confessional ethnography

Confessional ethnography Christian fogarolli

Christian fogarolli Western religion vs eastern religion

Western religion vs eastern religion Antony flew falsification

Antony flew falsification Seattle university school of theology and ministry

Seattle university school of theology and ministry Antony flew falsification

Antony flew falsification Ottawa school of theology and spirituality

Ottawa school of theology and spirituality Define theology proper

Define theology proper Proper_grace

Proper_grace The development of catholic trinitarian theology

The development of catholic trinitarian theology Biblical theology

Biblical theology Theology proper lecture notes

Theology proper lecture notes What is theology

What is theology Palamite theology

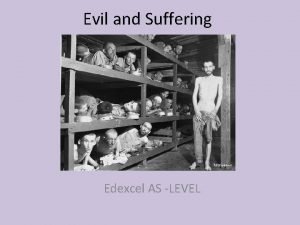

Palamite theology Irenaean theodicy strengths and weaknesses

Irenaean theodicy strengths and weaknesses Revelation 21:9-10

Revelation 21:9-10 R alan culpepper

R alan culpepper Arminian theology

Arminian theology Mike mazzalongo theology

Mike mazzalongo theology 5 pillars of reformed theology

5 pillars of reformed theology Jesus seminary

Jesus seminary Images from the crucible

Images from the crucible Theology of work

Theology of work Practical theology mpt

Practical theology mpt Praxis model of contextual theology

Praxis model of contextual theology The crucible act 3 vocabulary

The crucible act 3 vocabulary Theology of self care

Theology of self care Gnostic gospels summary

Gnostic gospels summary New creation theology

New creation theology Theology of missions

Theology of missions Process theology

Process theology Lakeside institute of theology

Lakeside institute of theology Mono theology

Mono theology Natural capital and natural income

Natural capital and natural income Natural hazards vs natural disasters

Natural hazards vs natural disasters Religion and society study design

Religion and society study design