Igneous Petrology PETROGRAPHY The description and systematic classification

- Slides: 61

Igneous Petrology

PETROGRAPHY The description and systematic classification of rocks, aided by the microscopic examination of thin sections. PETROLOGY The study of the origin, occurrence, structure and history of rocks, much broader process/study than petrography. PETROGENESIS A branch of petrology dealing with the origin and formation of rocks. Involves a combination of mineralogical, chemical and field data. Petrologic, petrographic, and petrogenetic studies can be applied to igneous, metamorphic or sedimentary rocks.

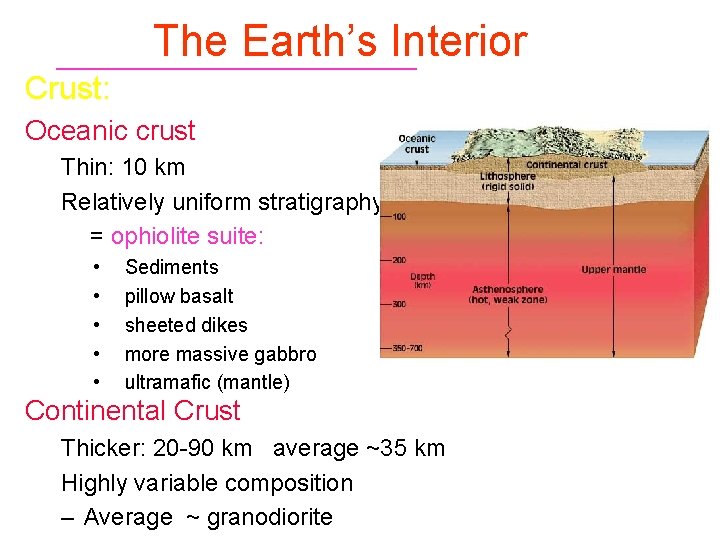

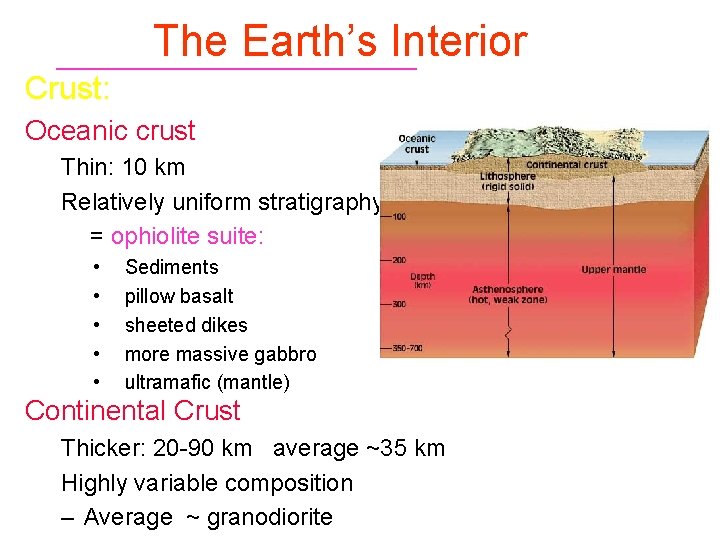

The Earth’s Interior Crust: Oceanic crust Thin: 10 km Relatively uniform stratigraphy = ophiolite suite: • • • Sediments pillow basalt sheeted dikes more massive gabbro ultramafic (mantle) Continental Crust Thicker: 20 -90 km average ~35 km Highly variable composition – Average ~ granodiorite

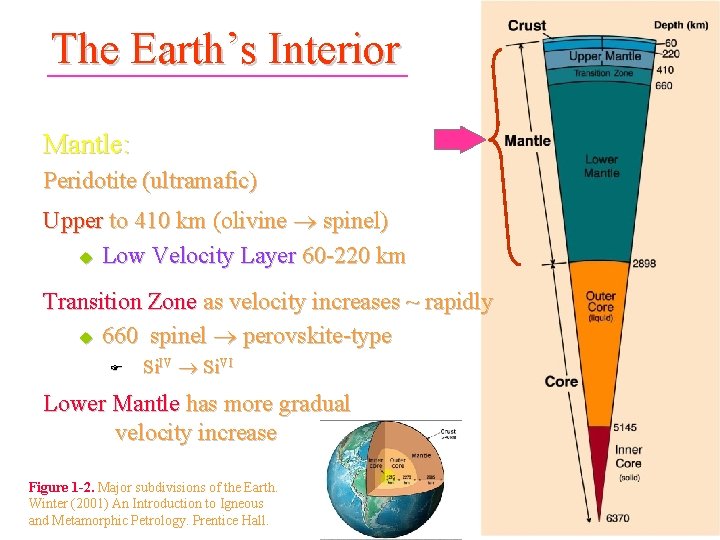

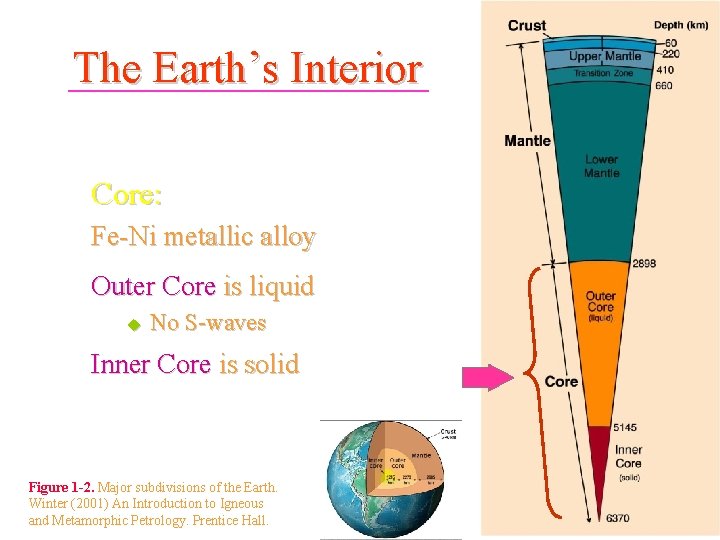

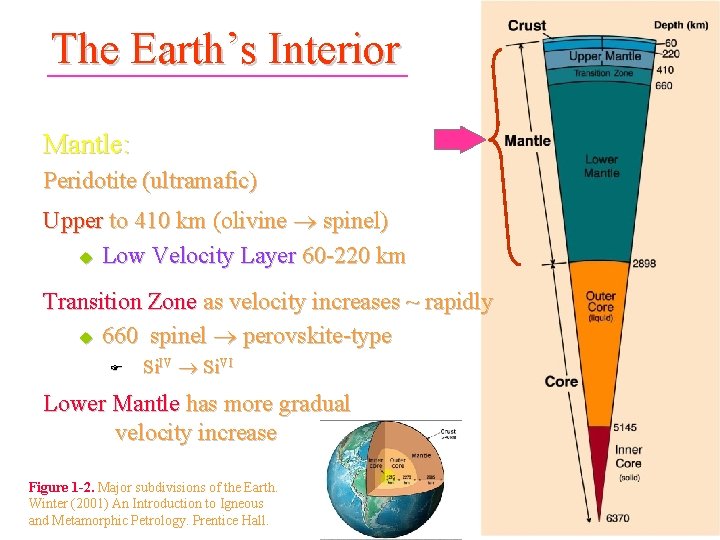

The Earth’s Interior Mantle: Peridotite (ultramafic) Upper to 410 km (olivine ® spinel) u Low Velocity Layer 60 -220 km Transition Zone as velocity increases ~ rapidly u 660 spinel ® perovskite-type F Si. IV ® Si. VI Lower Mantle has more gradual velocity increase Figure 1 -2. Major subdivisions of the Earth. Winter (2001) An Introduction to Igneous and Metamorphic Petrology. Prentice Hall.

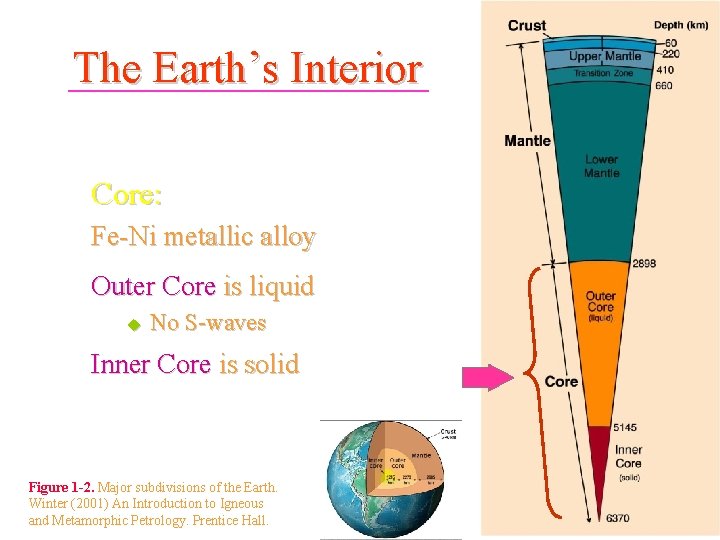

The Earth’s Interior Core: Fe-Ni metallic alloy Outer Core is liquid u No S-waves Inner Core is solid Figure 1 -2. Major subdivisions of the Earth. Winter (2001) An Introduction to Igneous and Metamorphic Petrology. Prentice Hall.

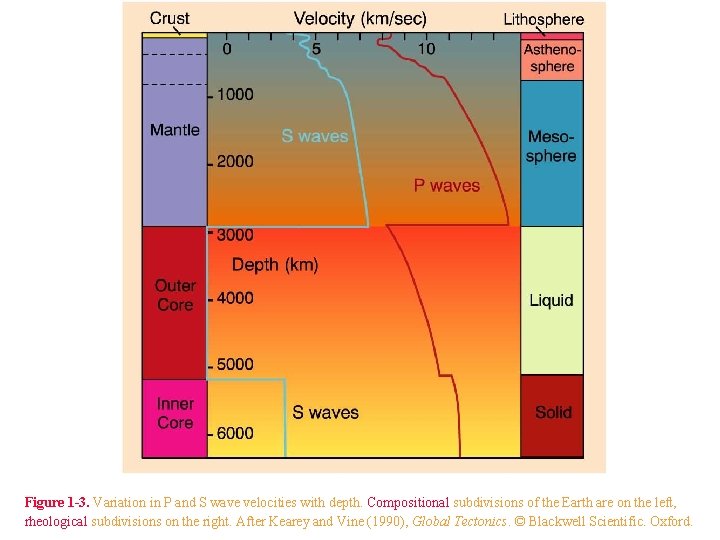

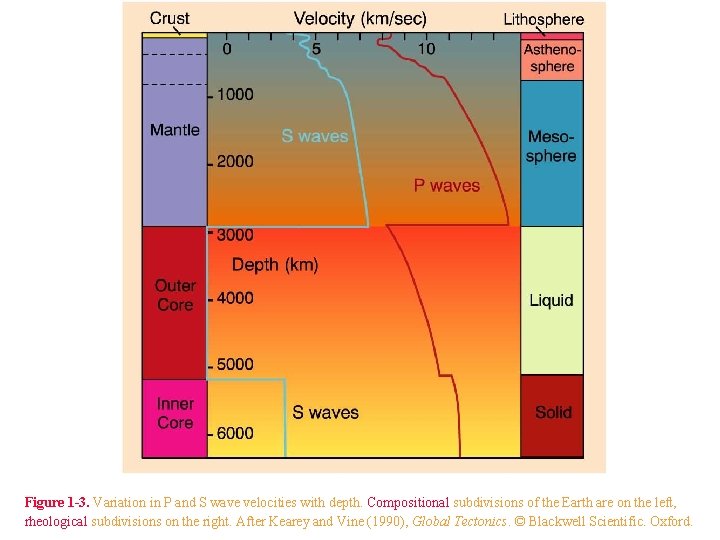

Figure 1 -3. Variation in P and S wave velocities with depth. Compositional subdivisions of the Earth are on the left, rheological subdivisions on the right. After Kearey and Vine (1990), Global Tectonics. © Blackwell Scientific. Oxford.

NOMENCLATURE AND CLASSIFICATION

-Formation of minerals in an igneous rocks is controlled by the chemical composition of the magma and the physical- chemical conditions present during crystallization. - Mineralogical composition and texture are used to describe, name and classify rocks. - Both overall chemistry ( whole-rock chemistry) and the chemistry of constitute minerals offer clues to igneous rock origins. - Studies of rock chemistry reveal where magmas form and how they are modified before they solidify. - the problem in rock classification is the selection of a basis for classification. - proposed classifications use texture, mineralogy, chemistry, geographic location and rock associations.

-Systems of nomenclature and classification may reflect: genetic, textural, chemical or mineralogical features. GENETIC basic system which classifies rocks on the basis of where they form. plutonic - at depth hypabyssal - intermediate depth volcanic - on the Earth's surface. This system is not very practical, but it serves as a first approximation, it tells nothing about mineralogy, chemistry of the rocks and can not distinguish basalt from rhyolite.

-TEXTURAL relies on the grain size of individual minerals in the rock. aphanitic - fine grained < 1 mm phaneritic - medium grained 1 to 5 mm coarse grained (pegmatitic) > 5 mm This system has the same shortcomings as a genetic classification, however specific textures present may aid in classification, e. g. , phenocryst, ophitic, coronas, but these are not indicative of a specific environment of formation or a specific lithology.

-CHEMICAL This type of classification requires a complete chemical analysis of the rock A chemical classification system has been proposed for volcanic rocks and a comparable scheme for plutonic rocks is not available. This leaves us with a system based on mineralogy.

MINERALOGICAL The one gaining application is the result of several years work by the IUGS Subcommission on the Classification of Igneous Rocks or Streckeissen Classification.

CLASSIFICATION SYSTEMS

Several aspects which historically have played and continue to play a role in the classification of igneous rocks should also be considered. GRADATION IN SILICA CONTENT - referred to as acid or basic, implying a range of silica content. Acidic > 66 wt% Si. O 2 Granites ~ 72 wt% Si. O 2, granodiorites ~ 68 wt% Si. O 2 Intermediate - 52 to 66 wt% Si. O 2 Andesite 57 wt% Si. O 2 Basic - 45 to 52 Wt% Si. O 2 Basalts range from 48 to 50 wt% Ultrabasic - < 45 wt% Si. O 2 peridotites 41 to 42 wt% Si. O 2

COLOUR GRADATION Felsic rocks are light coloured, contain felsic minerals (e. g. qtz, feldspar, feldspathoids) which are themselves light in colour and have a low density which contribute to the pale colour of the rock. Mafic Rocks are denser and dark coloured, the result of containing mafic minerals (pyroxene, amphibole, olivine, biotite). These minerals contribute to the green, brown and black colour of these rocks.

Chemistry of Igneous rocks

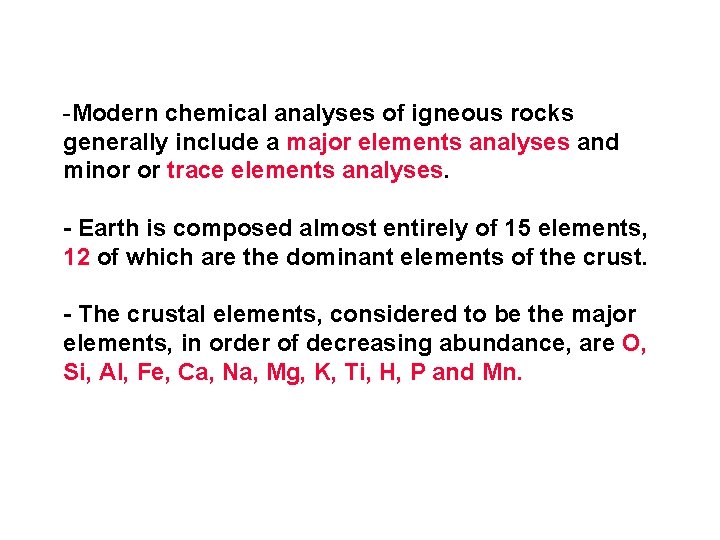

-Modern chemical analyses of igneous rocks generally include a major elements analyses and minor or trace elements analyses. - Earth is composed almost entirely of 15 elements, 12 of which are the dominant elements of the crust. - The crustal elements, considered to be the major elements, in order of decreasing abundance, are O, Si, Al, Fe, Ca, Na, Mg, K, Ti, H, P and Mn.

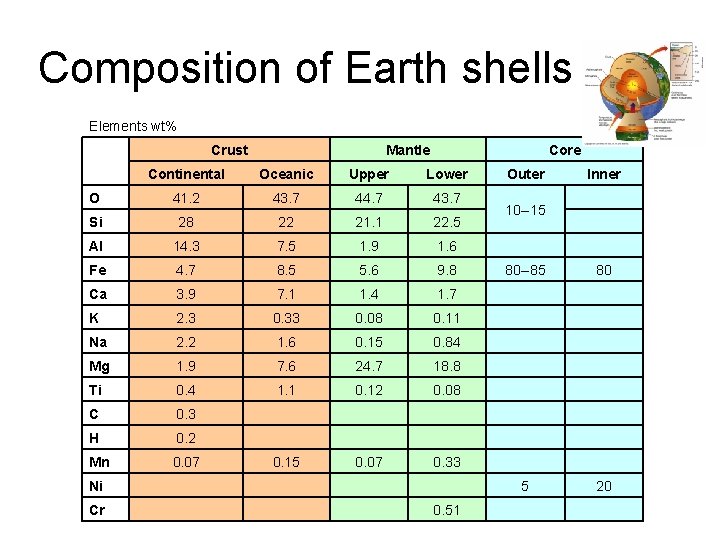

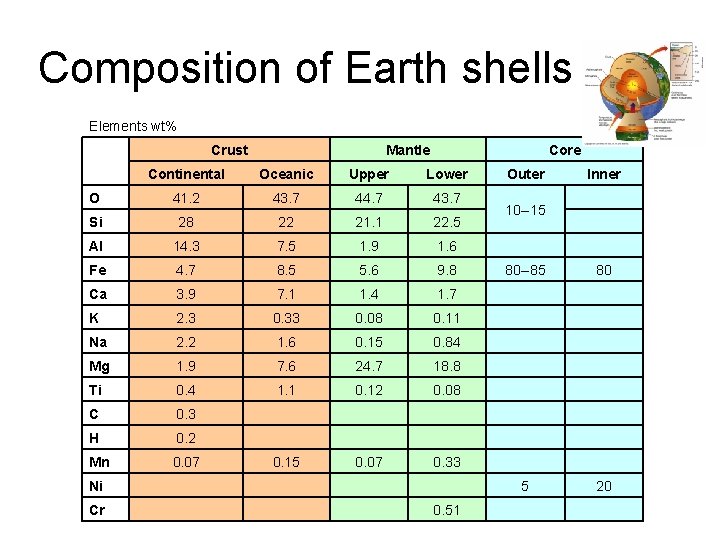

Composition of Earth shells Elements wt% Crust Mantle Core Continental Oceanic Upper Lower Outer O 41. 2 43. 7 44. 7 43. 7 Si 28 22 21. 1 22. 5 Al 14. 3 7. 5 1. 9 1. 6 Fe 4. 7 8. 5 5. 6 9. 8 80 --85 80 Ca 3. 9 7. 1 1. 4 1. 7 K 2. 3 0. 33 0. 08 0. 11 Na 2. 2 1. 6 0. 15 0. 84 Mg 1. 9 7. 6 24. 7 18. 8 Ti 0. 4 1. 1 0. 12 0. 08 C 0. 3 H 0. 2 Mn 0. 07 0. 15 0. 07 0. 33 Ni 5 20 Cr 0. 51 10 --15 Inner

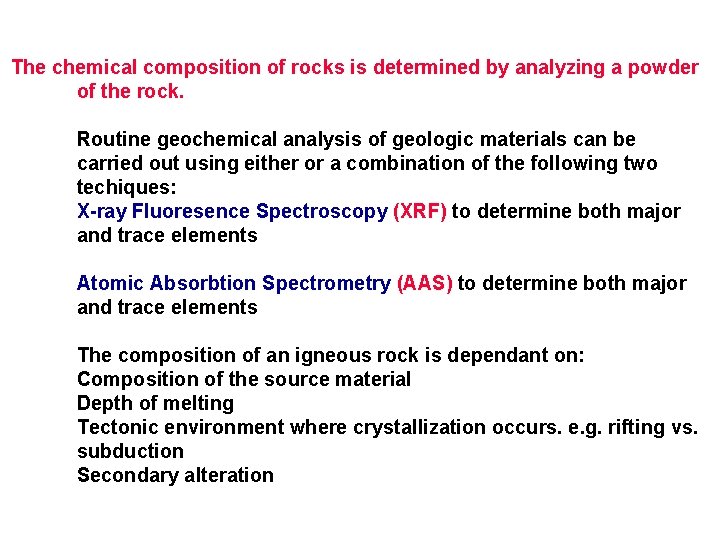

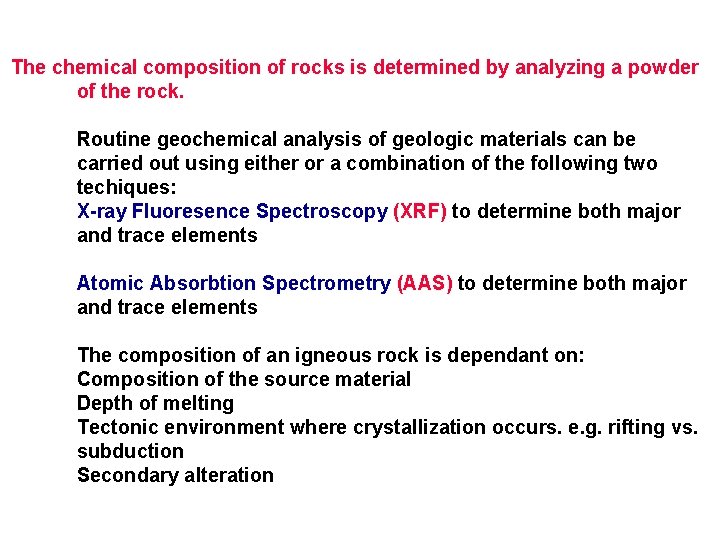

The chemical composition of rocks is determined by analyzing a powder of the rock. Routine geochemical analysis of geologic materials can be carried out using either or a combination of the following two techiques: X-ray Fluoresence Spectroscopy (XRF) to determine both major and trace elements Atomic Absorbtion Spectrometry (AAS) to determine both major and trace elements The composition of an igneous rock is dependant on: Composition of the source material Depth of melting Tectonic environment where crystallization occurs. e. g. rifting vs. subduction Secondary alteration

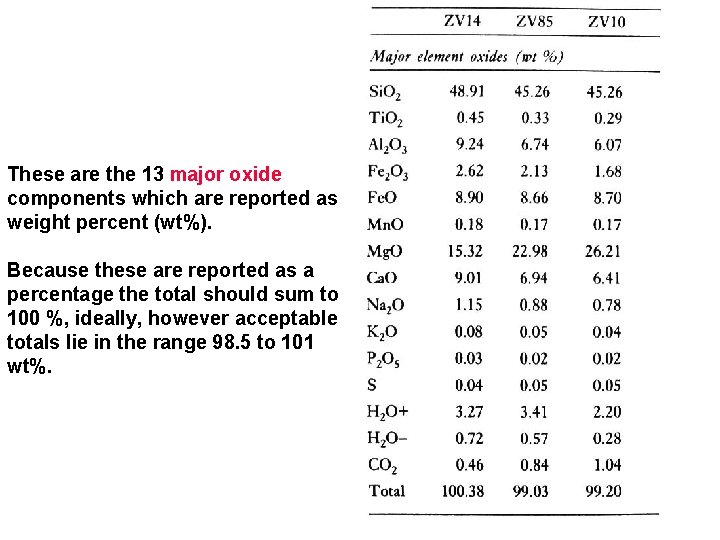

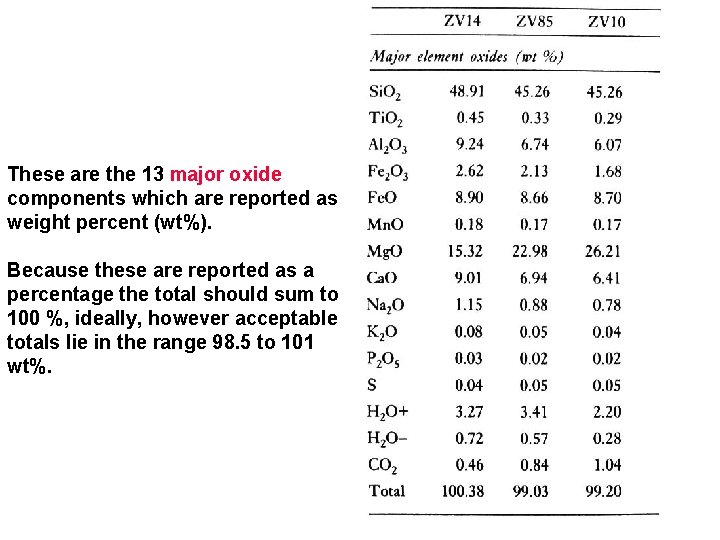

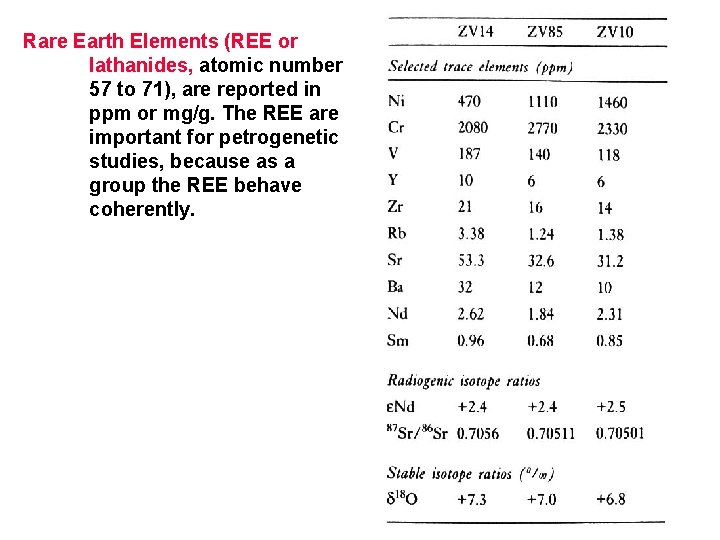

These are the 13 major oxide components which are reported as weight percent (wt%). Because these are reported as a percentage the total should sum to 100 %, ideally, however acceptable totals lie in the range 98. 5 to 101 wt%.

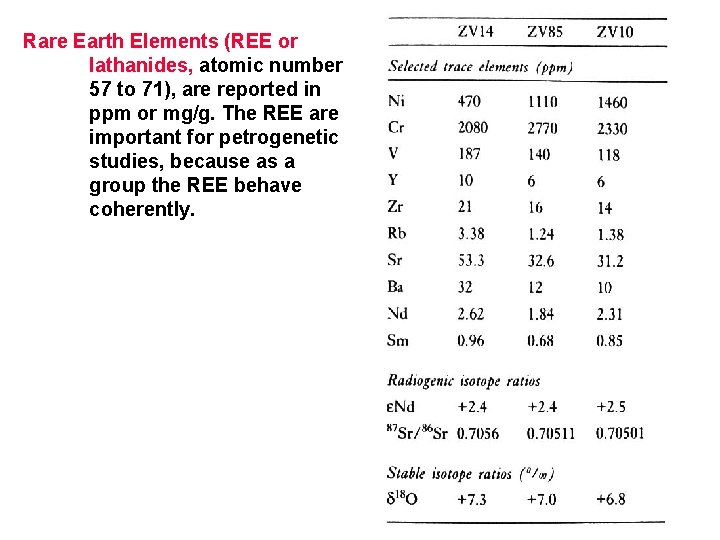

Rare Earth Elements (REE or lathanides, atomic number 57 to 71), are reported in ppm or mg/g. The REE are important for petrogenetic studies, because as a group the REE behave coherently.

SATURATION CONCEPT Used in reference to the Si. O 2 and Al 2 O 3 which are the two most abundant components of igneous rocks. Si. O 2 Saturation Minerals present in igneous rocks can be divided into two groups: Those which are compatible with quartz or primary Si. O 2 mineral (tridymite, cristobalite) these minerals are saturated with respect to Si, e. g feldspars, pyroxenes. Those which never occur with a primary silica mineral. These are undersaturated minerals, e. g. Mg-rich olivine, nepheline. The occurrence of quartz with an undersaturated mineral causes a reaction between the two minerals to form a saturated mineral. 2 Si. O 2 + Na. Al. Si. O 4 ===> Na. Al. Si 3 O 8 Qtz + Ne ===> Albite Si. O 2 + Mg 2 Si. O 4 ===> 2 Mg. Si. O 3 Qtz + Ol ===> En

Rock Classification (Silica saturation) Oversaturated - contains primary silica mineral Saturated - contains neither quartz nor an unsaturated mineral Unsaturated - contains unsaturated minerals

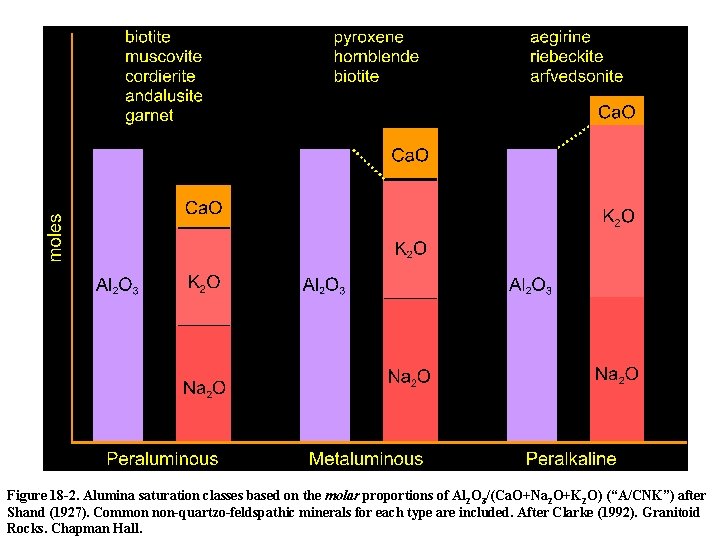

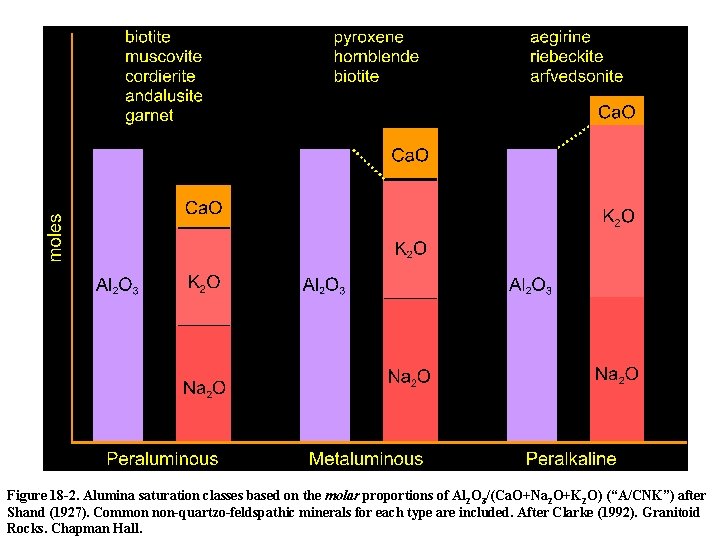

Al 2 O 3 Saturation Four subdivisions of rocks independant of silica saturation, based on the molecular proportions of Al 2 O 3, Na 2 O, K 2 O and Ca. O applied mainly to granitic lithologies. Peraluminous - Al 2 O 3 > (Na 2 O + K 2 O + Ca. O) Metaluminous - Al 2 O 3 < (Na 2 O + K 2 O + Ca. O) but Al 2 O 3 > (Na 2 O + K 2 O) Subaluminous - Al 2 O 3 = (Na 2 O + K 2 O) Peralkaline - Al 2 O 3 < (Na 2 O + K 2 O)

VARIATION DIAGRAMS

A main objective of any research program on igneous rocks is to describe and display chemical variations for simplicity and to facilitate condensing information. The best way to simplify and condense analytical data is by graphical means.

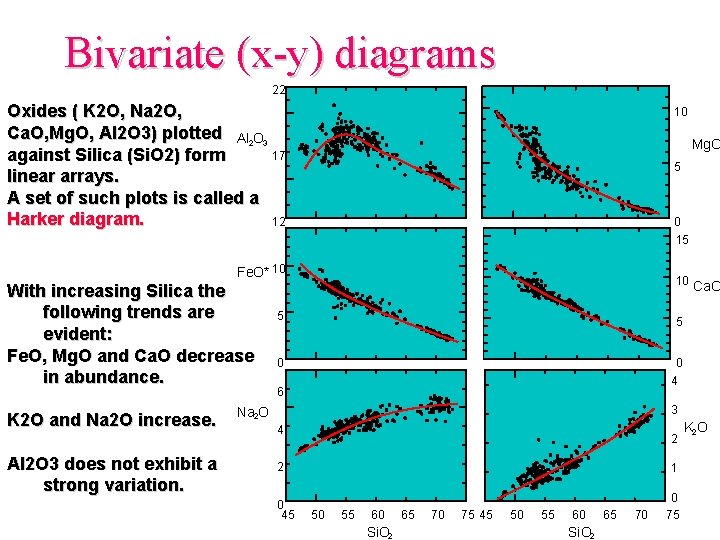

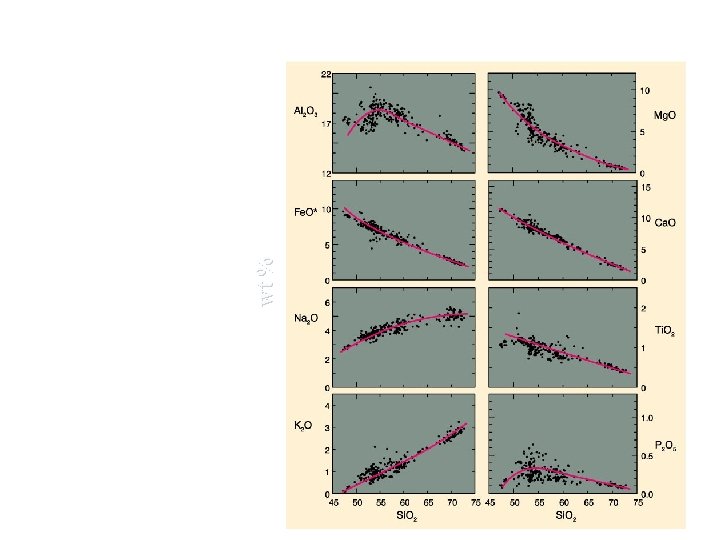

Harker Diagrams The oldest method is the variation diagram or Harker diagram which dates from 1909, and plots oxides of elements against Si. O 2.

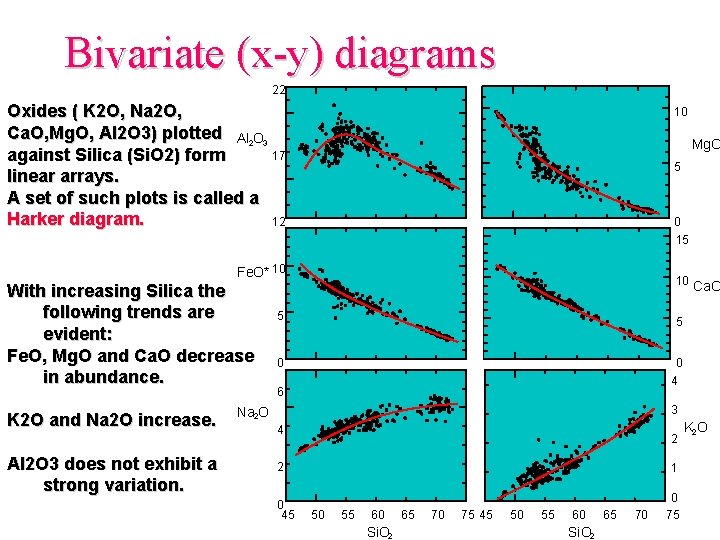

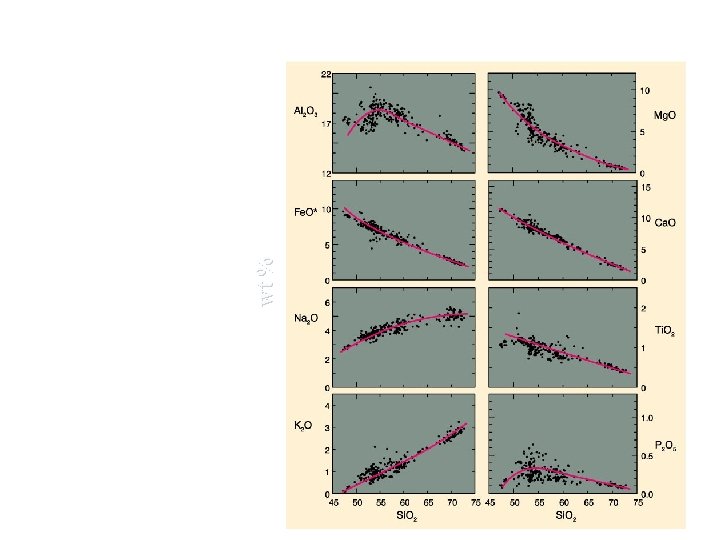

Bivariate (x-y) diagrams 22 Oxides ( K 2 O, Na 2 O, Ca. O, Mg. O, Al 2 O 3) plotted Al 2 O 3 17 against Silica (Si. O 2) form linear arrays. A set of such plots is called a Harker diagram. 12 10 Mg. O 5 0 15 Fe. O* 10 With increasing Silica the following trends are evident: Fe. O, Mg. O and Ca. O decrease in abundance. Na 2 O K 2 O and Na 2 O increase. Al 2 O 3 does not exhibit a strong variation. 10 5 Ca. O 5 0 0 4 6 3 4 2 2 0 45 1 50 55 60 Si. O 2 65 70 75 45 50 55 60 Si. O 2 65 70 0 75 K 2 O

wt %

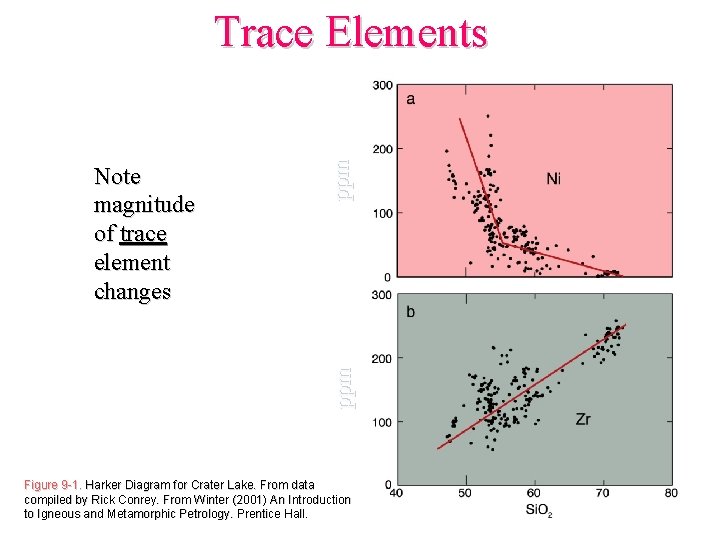

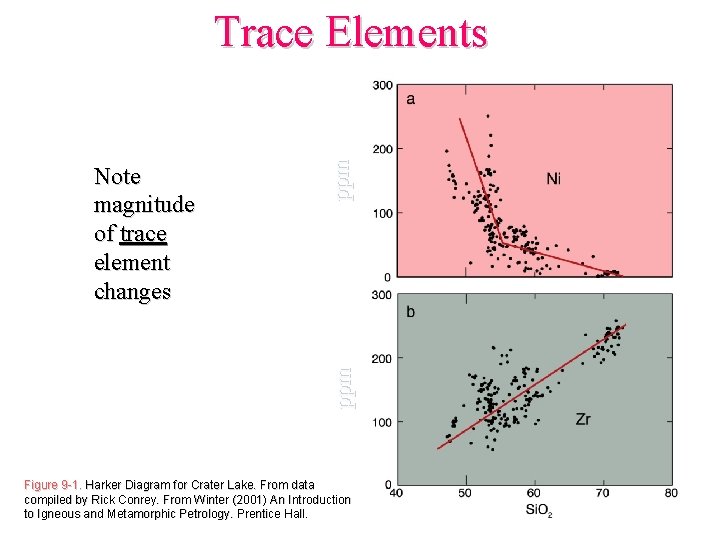

ppm Note magnitude of trace element changes ppm Trace Elements Figure 9 -1. Harker Diagram for Crater Lake. From data compiled by Rick Conrey. From Winter (2001) An Introduction to Igneous and Metamorphic Petrology. Prentice Hall.

Triangular Variation Diagrams

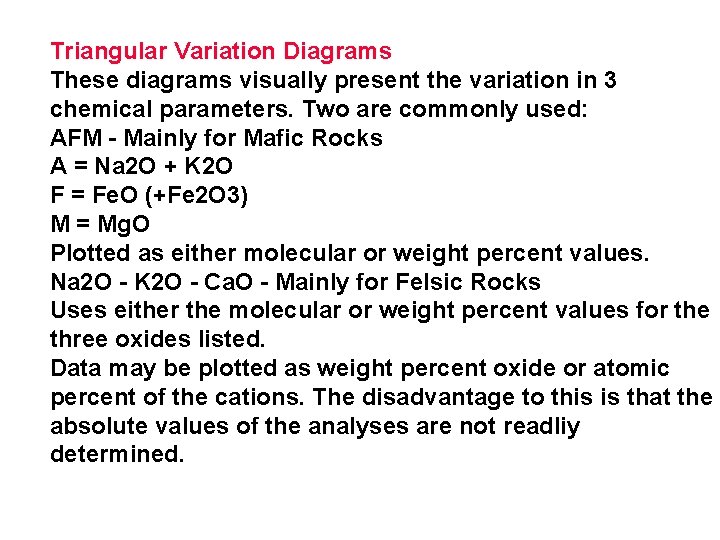

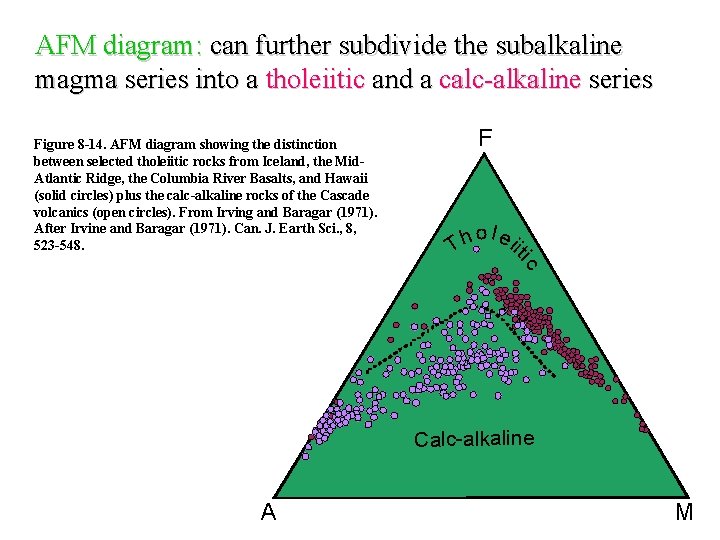

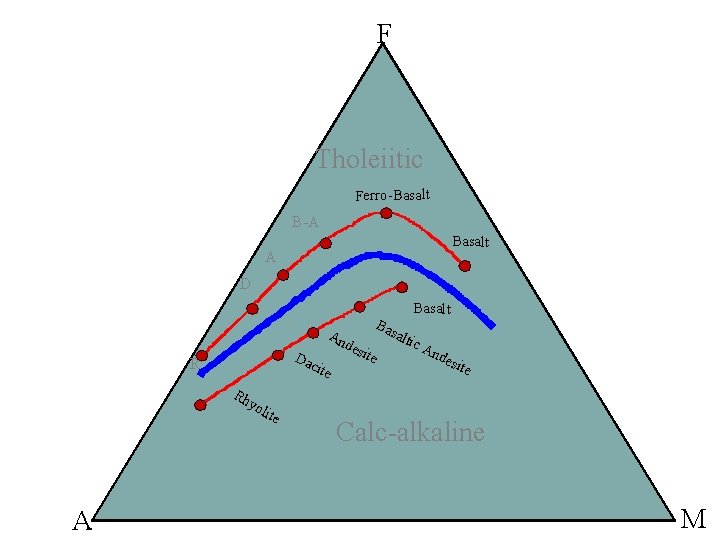

Triangular Variation Diagrams These diagrams visually present the variation in 3 chemical parameters. Two are commonly used: AFM - Mainly for Mafic Rocks A = Na 2 O + K 2 O F = Fe. O (+Fe 2 O 3) M = Mg. O Plotted as either molecular or weight percent values. Na 2 O - K 2 O - Ca. O - Mainly for Felsic Rocks Uses either the molecular or weight percent values for the three oxides listed. Data may be plotted as weight percent oxide or atomic percent of the cations. The disadvantage to this is that the absolute values of the analyses are not readliy determined.

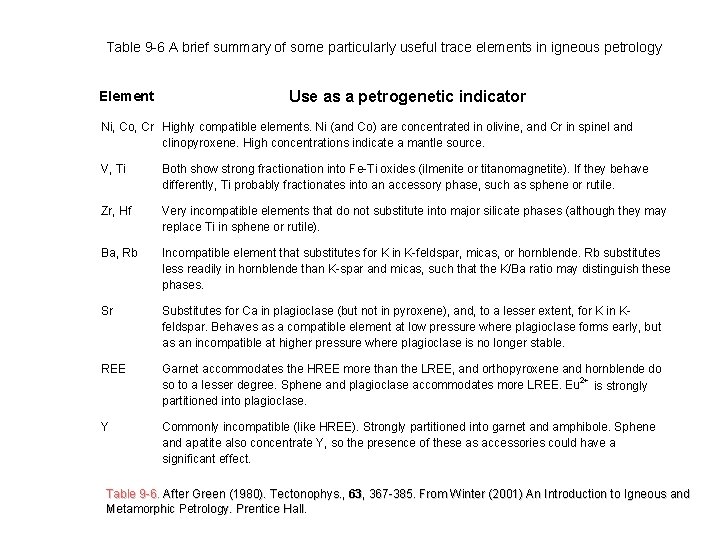

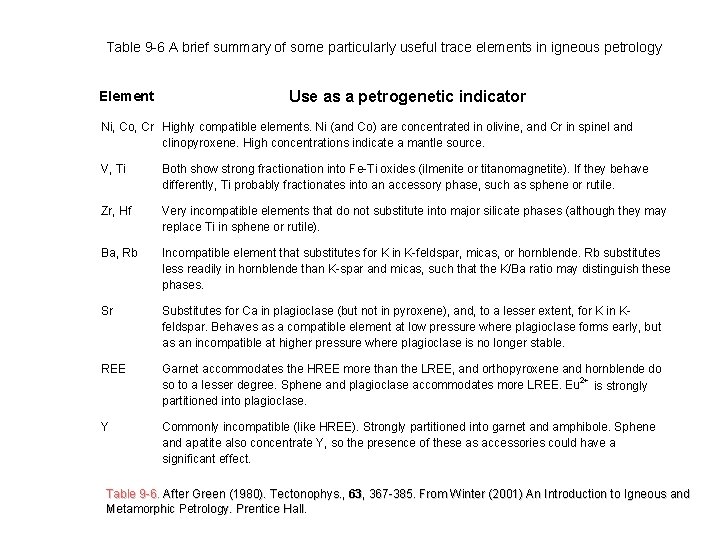

Table 9 -6 A brief summary of some particularly useful trace elements in igneous petrology Element Use as a petrogenetic indicator Ni, Co, Cr Highly compatible elements. Ni (and Co) are concentrated in olivine, and Cr in spinel and clinopyroxene. High concentrations indicate a mantle source. V, Ti Both show strong fractionation into Fe-Ti oxides (ilmenite or titanomagnetite). If they behave differently, Ti probably fractionates into an accessory phase, such as sphene or rutile. Zr, Hf Very incompatible elements that do not substitute into major silicate phases (although they may replace Ti in sphene or rutile). Ba, Rb Incompatible element that substitutes for K in K-feldspar, micas, or hornblende. Rb substitutes less readily in hornblende than K-spar and micas, such that the K/Ba ratio may distinguish these phases. Sr Substitutes for Ca in plagioclase (but not in pyroxene), and, to a lesser extent, for K in Kfeldspar. Behaves as a compatible element at low pressure where plagioclase forms early, but as an incompatible at higher pressure where plagioclase is no longer stable. REE Garnet accommodates the HREE more than the LREE, and orthopyroxene and hornblende do so to a lesser degree. Sphene and plagioclase accommodates more LREE. Eu 2+ is strongly partitioned into plagioclase. Y Commonly incompatible (like HREE). Strongly partitioned into garnet and amphibole. Sphene and apatite also concentrate Y, so the presence of these as accessories could have a significant effect. Table 9 -6. After Green (1980). Tectonophys. , 63 63, 367 -385. From Winter (2001) An Introduction to Igneous and Table 9 -6. After Green (1980). Tectonophys Metamorphic Petrology. Prentice Hall.

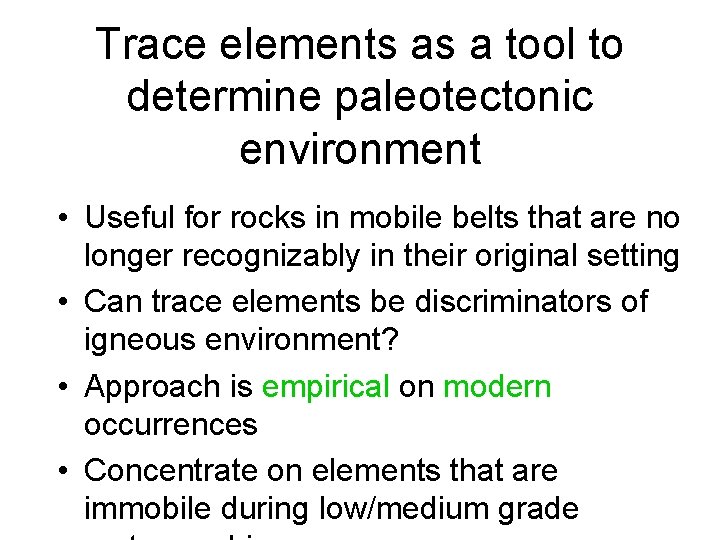

Trace elements as a tool to determine paleotectonic environment • Useful for rocks in mobile belts that are no longer recognizably in their original setting • Can trace elements be discriminators of igneous environment? • Approach is empirical on modern occurrences • Concentrate on elements that are immobile during low/medium grade

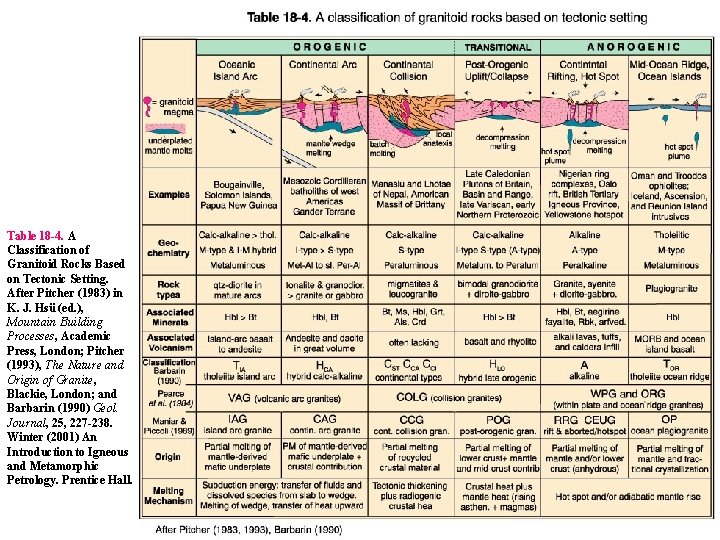

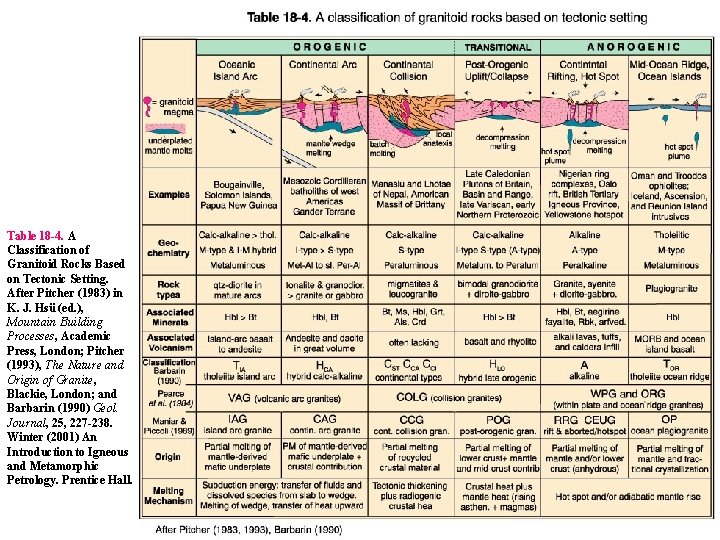

Table 18 -4. A Classification of Granitoid Rocks Based on Tectonic Setting. After Pitcher (1983) in K. J. Hsü (ed. ), Mountain Building Processes, Academic Press, London; Pitcher (1993), The Nature and Origin of Granite, Blackie, London; and Barbarin (1990) Geol. Journal, 25, 227 -238. Winter (2001) An Introduction to Igneous and Metamorphic Petrology. Prentice Hall.

Si. O 2 is generally chosen because it is the most abundant oxide in igneous rocks and exhibits a wide variation in composition. This type of graphical presentation is useful for large quantities of analytical data and yields an approximation of inter-element variations for a group of samples. No genetic link can be inferred from Harker diagrams, i. e. that the lowest Si. O 2 content present on the diagram represents the original or first liquid, for the group of samples presented, from which all other liquids were derived.

• Harker diagrams: Si. O 2 vs. oxide. • The meaning of geochemical trends: can be interpreted as magmatic “evolution” from “primitive” to “differenciated” rocks. More or less implicitly assumes fractional crystallization. • The nature of the phases crystallizing can be inferred from the shape of the trends. Ex. : decreasing Fe, Mg = precipitation of mafic minerals.

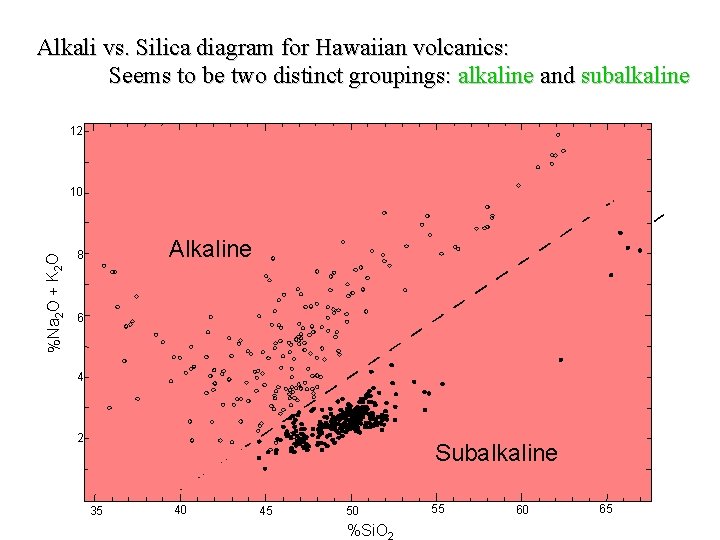

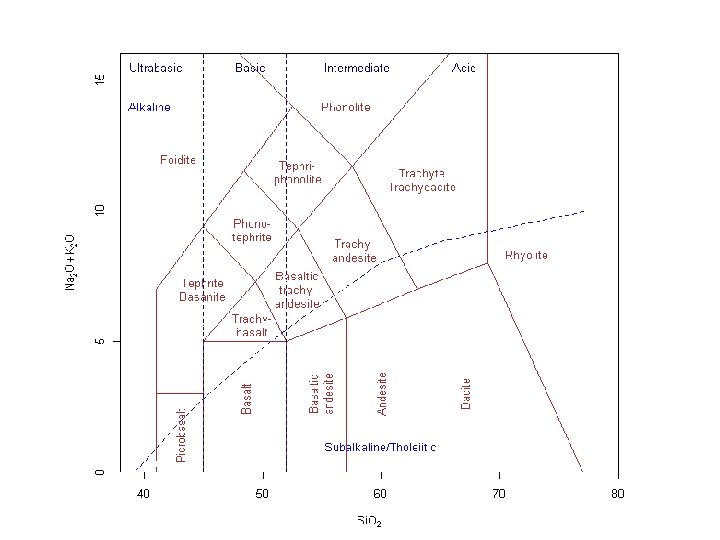

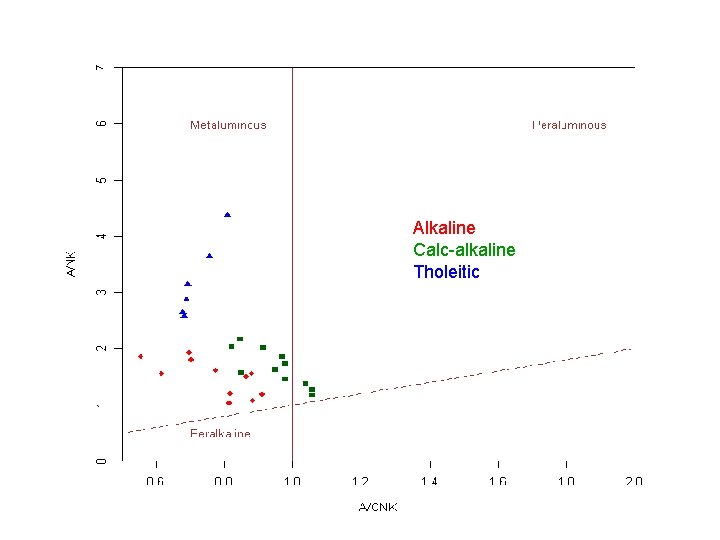

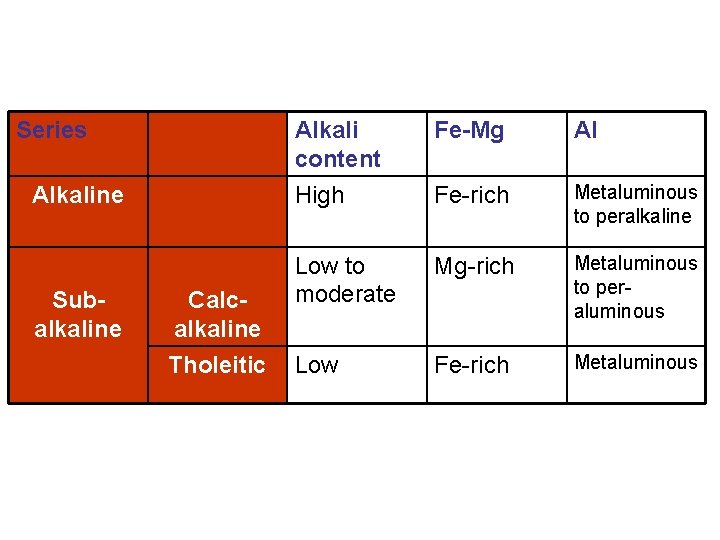

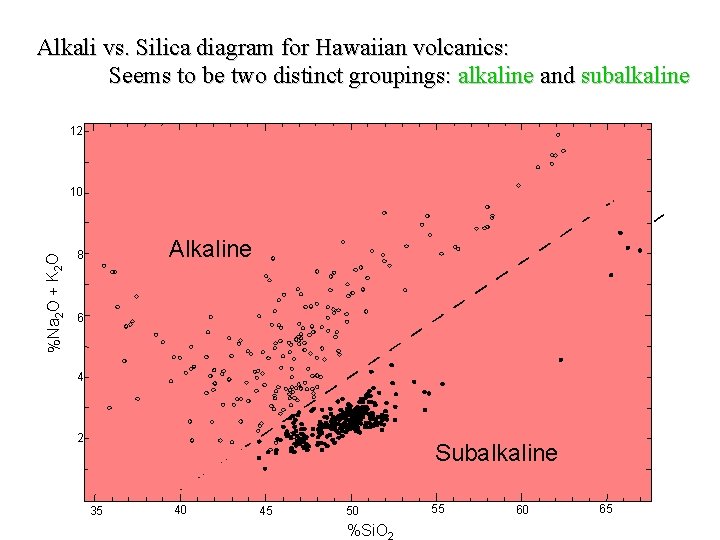

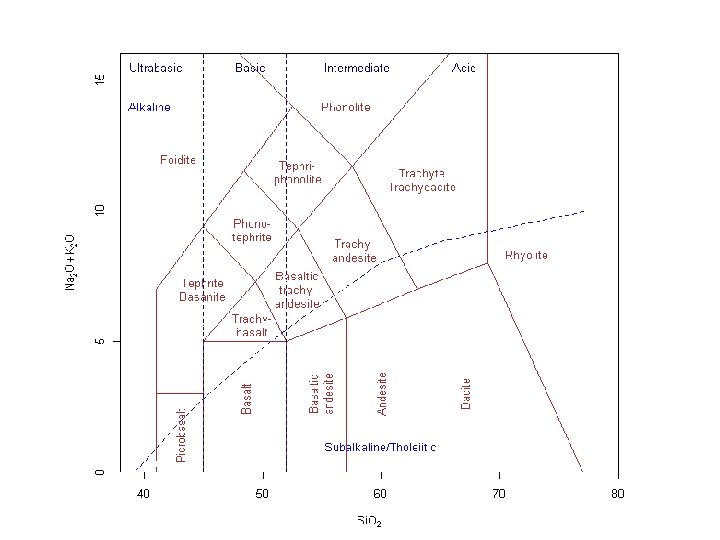

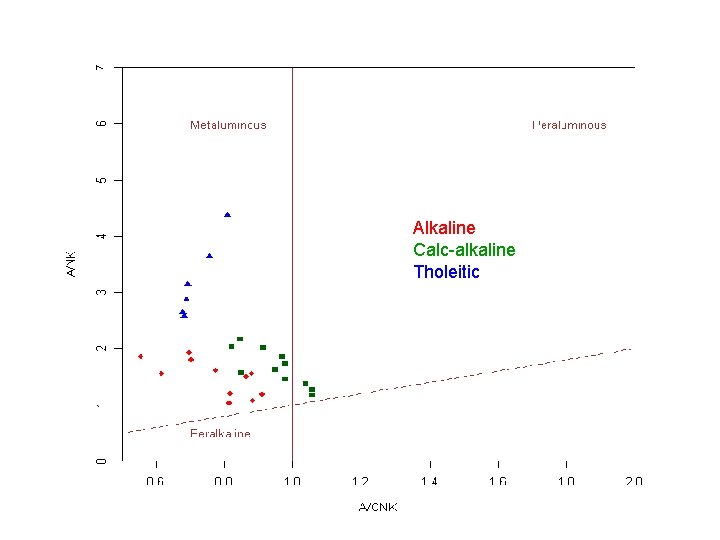

Magmatic series: reflect first order differences between rock groups. • TAS diagram separates alkali and sub-alkali series • Sub-alkali series are further separated on the basis of their Fe -Mg contens (AFM diagram) into tholeitic and calc-alkaline In addition, important role of the relative proportions of Al 2 O 3 and Ca. O-Na 2 O-K 2 O • A>CNK: Peraluminous rocks. Have Al-rich minerals such as biotite, muscovite, garnet, cordierite… • A<CNK: o. . and A>NK: Metaluminous. No particular minerals, mafics are pyroxene, amphibole, biotite o. . and A<NK: peralkaline rocks. Alklai-rich minerals such as alkali amphiboles and pyroxenes.

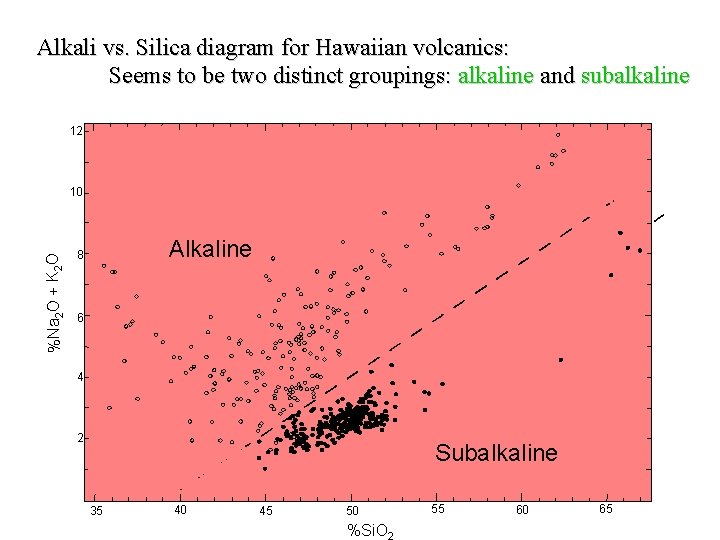

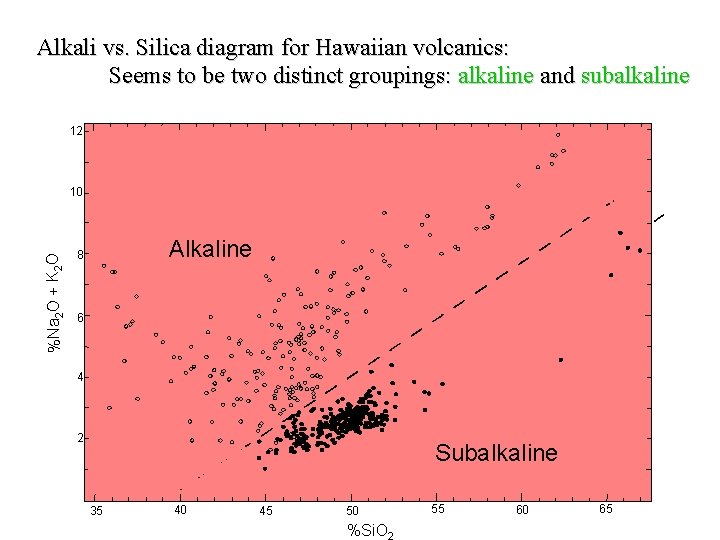

Alkali vs. Silica diagram for Hawaiian volcanics: Seems to be two distinct groupings: alkaline and subalkaline 12 %Na 2 O + K 2 O 10 Alkaline 8 6 4 2 Subalkaline 35 40 45 50 %Si. O 55 60 65

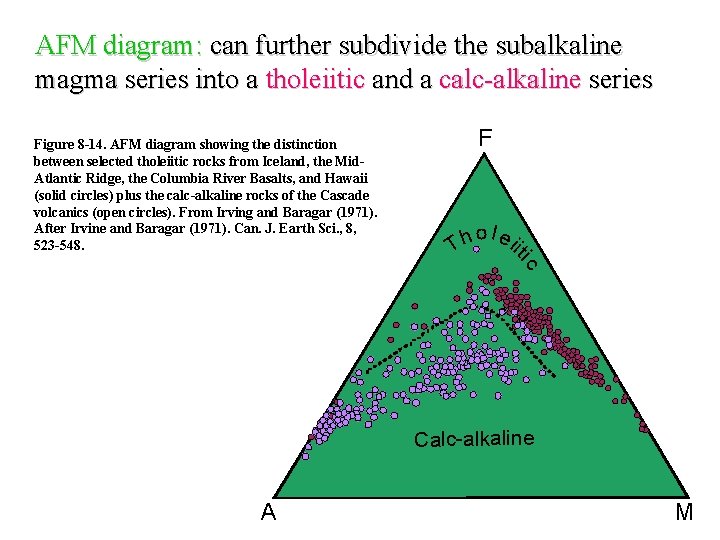

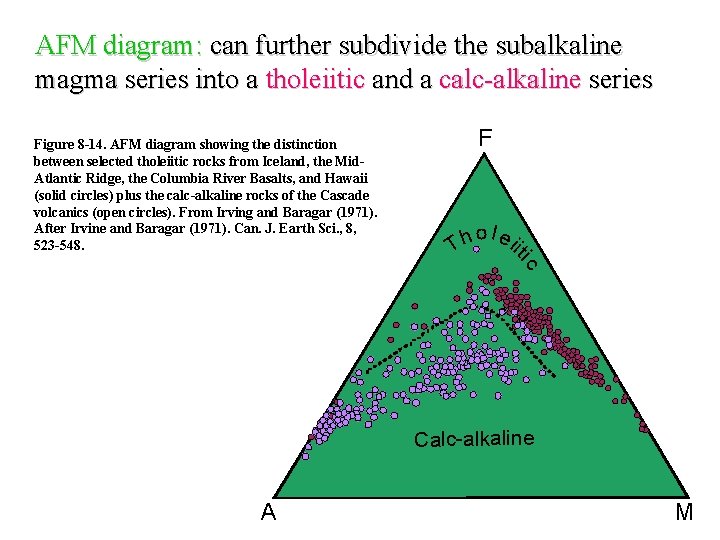

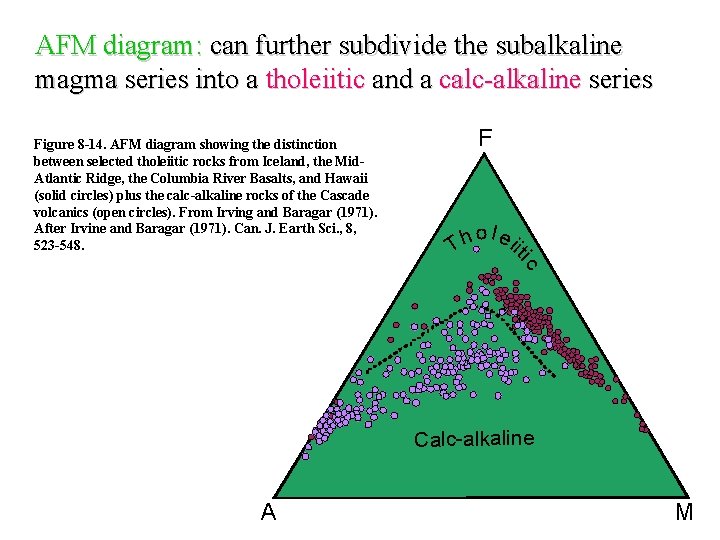

AFM diagram: can further subdivide the subalkaline magma series into a tholeiitic and a calc-alkaline series Figure 8 -14. AFM diagram showing the distinction between selected tholeiitic rocks from Iceland, the Mid. Atlantic Ridge, the Columbia River Basalts, and Hawaii (solid circles) plus the calc-alkaline rocks of the Cascade volcanics (open circles). From Irving and Baragar (1971). After Irvine and Baragar (1971). Can. J. Earth Sci. , 8, 523 -548. o l ei h it T ic F Calc-alkaline A M

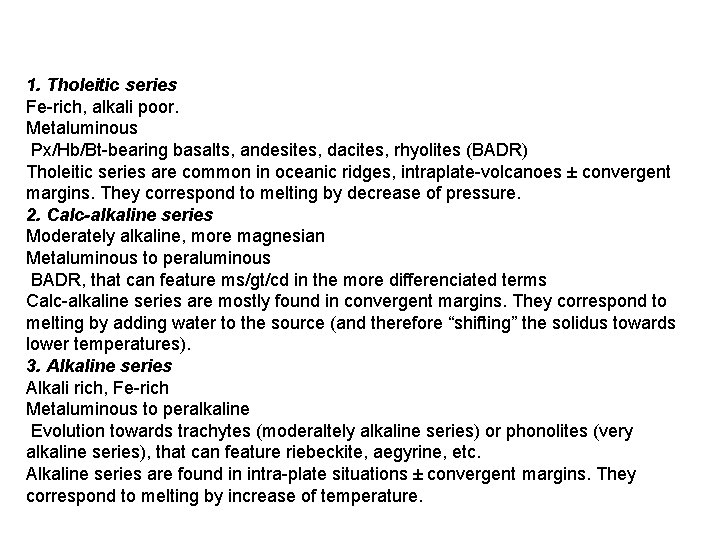

1. Tholeitic series Fe-rich, alkali poor. Metaluminous Px/Hb/Bt-bearing basalts, andesites, dacites, rhyolites (BADR) Tholeitic series are common in oceanic ridges, intraplate-volcanoes ± convergent margins. They correspond to melting by decrease of pressure. 2. Calc-alkaline series Moderately alkaline, more magnesian Metaluminous to peraluminous BADR, that can feature ms/gt/cd in the more differenciated terms Calc-alkaline series are mostly found in convergent margins. They correspond to melting by adding water to the source (and therefore “shifting” the solidus towards lower temperatures). 3. Alkaline series Alkali rich, Fe-rich Metaluminous to peralkaline Evolution towards trachytes (moderaltely alkaline series) or phonolites (very alkaline series), that can feature riebeckite, aegyrine, etc. Alkaline series are found in intra-plate situations ± convergent margins. They correspond to melting by increase of temperature.

Fractionation Indices

To obtain a genetic link between analyses of a given suite of samples fractionation indices were developed. These indices attempt to the results of chemical analyses from an individual igneous suite into their correct evolutionary order. These indices are not realistic but several come close to such an order.

Mg. O Index This is used for basaltic rocks. Positive correlations are produced for Na 2 O, K 2 O, and P 2 O 5 indicating enrichment in these oxides with successive liquids. Negative correlations result for Ca. O. Mg-Fe Ratios Again used for basaltic rocks. These involve a ratio of Mg to Fe: Mg. O/Mg. O+Fe. O (ferrous) Mg. O/Mg. O+Fe 2 O 3 (ferric) Mg/Mg+Fe (uses atomic proportions of the cations). Normative Ab/Ab+An Based on the values of Na 2 O and Ca. O. Only good for rocks which crystallize plagioclase, not effected by mafic mineral formation. Generally applied to granites. The above three indices are only good for specific lithologies, and thus have a restricted application.

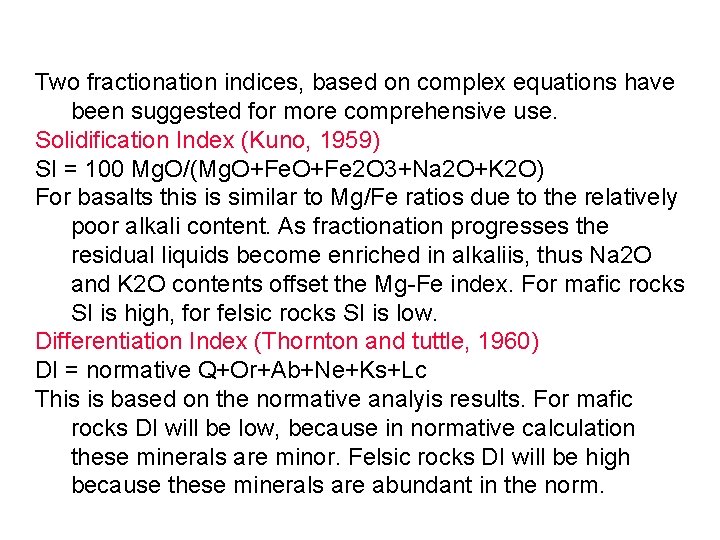

Two fractionation indices, based on complex equations have been suggested for more comprehensive use. Solidification Index (Kuno, 1959) SI = 100 Mg. O/(Mg. O+Fe 2 O 3+Na 2 O+K 2 O) For basalts this is similar to Mg/Fe ratios due to the relatively poor alkali content. As fractionation progresses the residual liquids become enriched in alkaliis, thus Na 2 O and K 2 O contents offset the Mg-Fe index. For mafic rocks SI is high, for felsic rocks SI is low. Differentiation Index (Thornton and tuttle, 1960) DI = normative Q+Or+Ab+Ne+Ks+Lc This is based on the normative analyis results. For mafic rocks DI will be low, because in normative calculation these minerals are minor. Felsic rocks DI will be high because these minerals are abundant in the norm.

Alkali vs. Silica diagram for Hawaiian volcanics: Seems to be two distinct groupings: alkaline and subalkaline 12 %Na 2 O + K 2 O 10 Alkaline 8 6 4 2 Subalkaline 35 40 45 50 %Si. O 55 60 65

AFM diagram: can further subdivide the subalkaline magma series into a tholeiitic and a calc-alkaline series Figure 8 -14. AFM diagram showing the distinction between selected tholeiitic rocks from Iceland, the Mid. Atlantic Ridge, the Columbia River Basalts, and Hawaii (solid circles) plus the calc-alkaline rocks of the Cascade volcanics (open circles). From Irving and Baragar (1971). After Irvine and Baragar (1971). Can. J. Earth Sci. , 8, 523 -548. o l ei h it T ic F Calc-alkaline A M

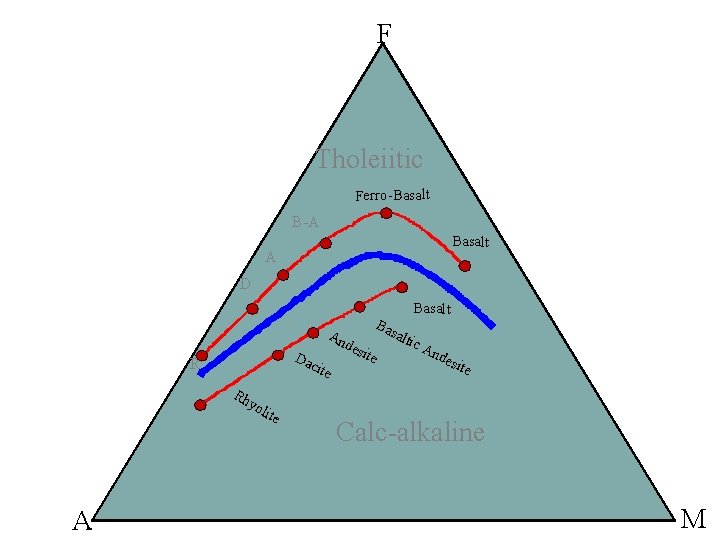

F Tholeiitic Ferro-Basalt B-A Basalt A D Basalt Da R An des cite Rh ite Ba sal tic An des ite yo A lite Calc-alkaline M

Figure 18 -2. Alumina saturation classes based on the molar proportions of Al 2 O 3/(Ca. O+Na 2 O+K 2 O) (“A/CNK”) after Shand (1927). Common non-quartzo-feldspathic minerals for each type are included. After Clarke (1992). Granitoid Rocks. Chapman Hall.

Alkaline Calc-alkaline Tholeitic

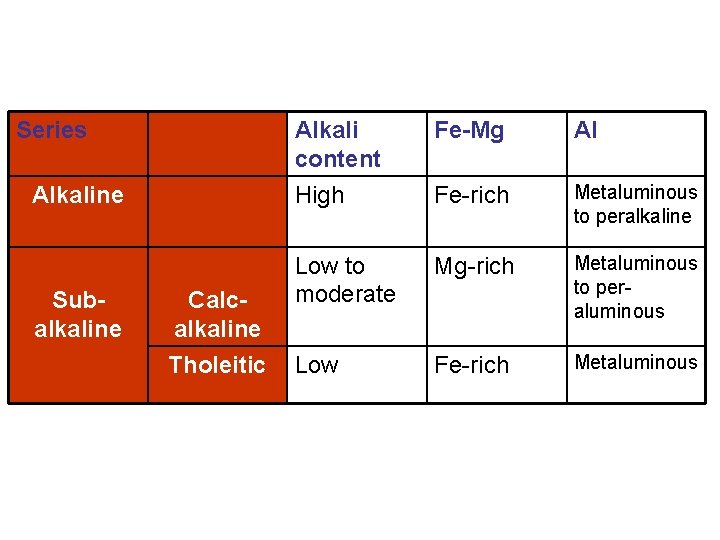

Series Alkaline Subalkaline Calcalkaline Tholeitic Alkali content High Fe-Mg Al Fe-rich Metaluminous to peralkaline Low to moderate Mg-rich Metaluminous to peraluminous Low Fe-rich Metaluminous

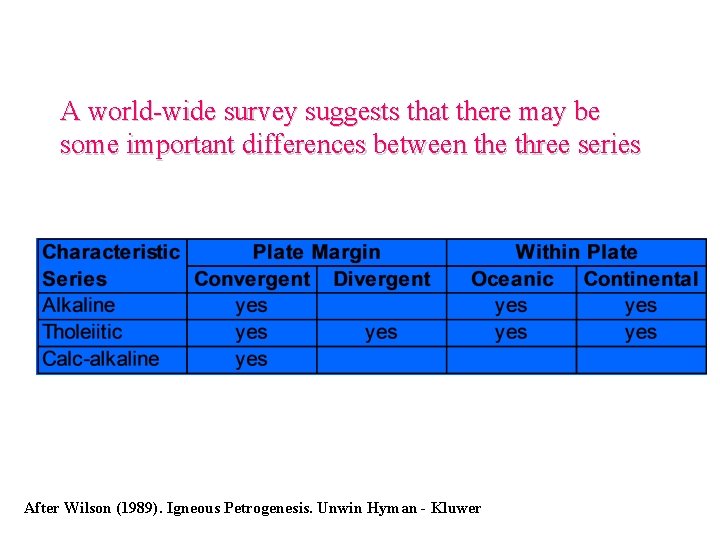

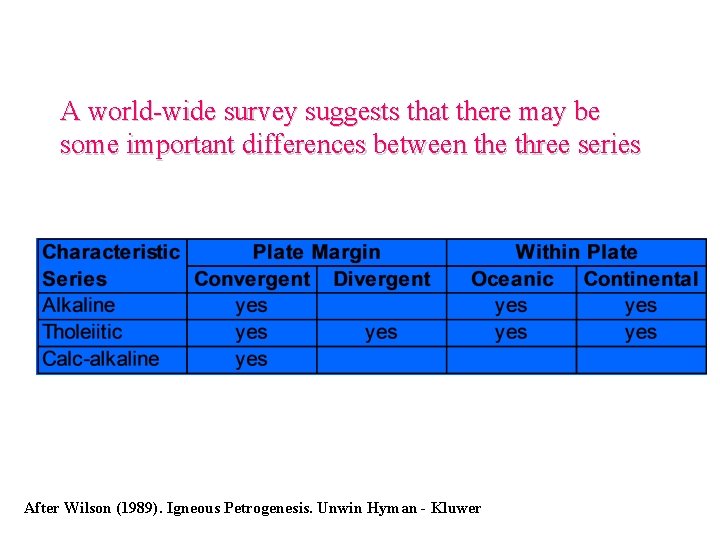

A world-wide survey suggests that there may be some important differences between the three series After Wilson (1989). Igneous Petrogenesis. Unwin Hyman - Kluwer

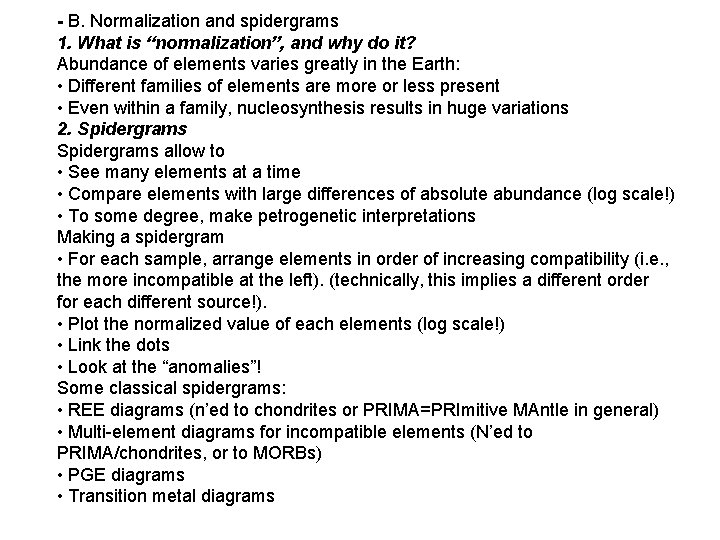

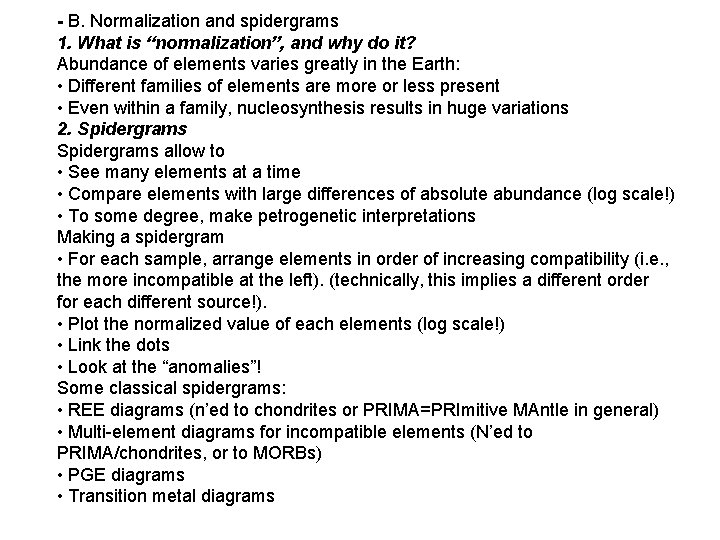

- B. Normalization and spidergrams 1. What is “normalization”, and why do it? Abundance of elements varies greatly in the Earth: • Different families of elements are more or less present • Even within a family, nucleosynthesis results in huge variations 2. Spidergrams allow to • See many elements at a time • Compare elements with large differences of absolute abundance (log scale!) • To some degree, make petrogenetic interpretations Making a spidergram • For each sample, arrange elements in order of increasing compatibility (i. e. , the more incompatible at the left). (technically, this implies a different order for each different source!). • Plot the normalized value of each elements (log scale!) • Link the dots • Look at the “anomalies”! Some classical spidergrams: • REE diagrams (n’ed to chondrites or PRIMA=PRImitive MAntle in general) • Multi-element diagrams for incompatible elements (N’ed to PRIMA/chondrites, or to MORBs) • PGE diagrams • Transition metal diagrams

MODAL ANALYSIS

Two types of analysis are useful when examining Igneous Rocks: Modal analysis - requires only a thin section, Normative analysis - requires a chemical analysis.

MODAL ANALYSIS Produces an accurate representation of the distribution and volume percent of the mineral within a thin section. Three methods of analysis are used: Measure the surface area of mineral grains of the same mineral, relative to the total surface area of the thin section. Measure the intercepts of each mineral along a series of lines. POINT COUNT - Count each mineral occurrence along a series of traverse line across a given thin section. For a statistically valid result > 2000 individual points must be counted. The number of grains counted, the spacing between points and successive traverse lines is dependant on the mean grain size of the sample.

Advantages One can compare rocks from different areas if you only have a thin section, no chemical analysis is required, using a petrographic microscope. Gives the maximum and minimum grain sizes. Disadvantages Meaningless if the sample has a preferred orientation of one or more minerals. Porphyritic rocks are difficult to count. Total area of sample must be sufficiently larger than the max. diameter of the smallest grain size.

NORMATIVE ANALYSIS OR NORM

Normative analysis is defined as the calculation of a theoretical assemblage of standard minerals for a rock based, on the whole rock chemical composition as determined by analytical techniques. The original purpose for the norm was essentially taxonomic. An elaborate classification scheme based on the normative mineral percentages was proposed. The classification groups together rocks of similar bulk composition irrespective of their mineralogy. Various types of NORMs have been proposed - CIPW, Niggli, Barth. Each of theses proposals has its own specific advantages and/or disadvantages. The CIPW norm, originally proposed in 1919, was proposed as a means of comparing and classifying all igneosu rocks for which chemical analyses wers available. The NORM takes it's name from the four authors who proposed it - Cross, Iddings, Pirsson and Washington. This NORM was very elegant and based on a number of simplifications: The magma crystallizes under anhydrous conditions so that no hydrous minerals (hornblende, biotite) are formed. The feromagnesium minerals are assumed to be free of Al 2 O 3. The Fe/Mg ratio for all feromagnesium minerals is assumed to be the same. Several minerals are assumed to be incompatible, thus nepheline and/or olivine never appear with quartz in the norm. Since the CIPW NORM was introduced in 1919 several other normative calculations have been suggested, e. g. Niggli norm, Barth mesonorm. The latter is used commonly when examining granitic rocks.

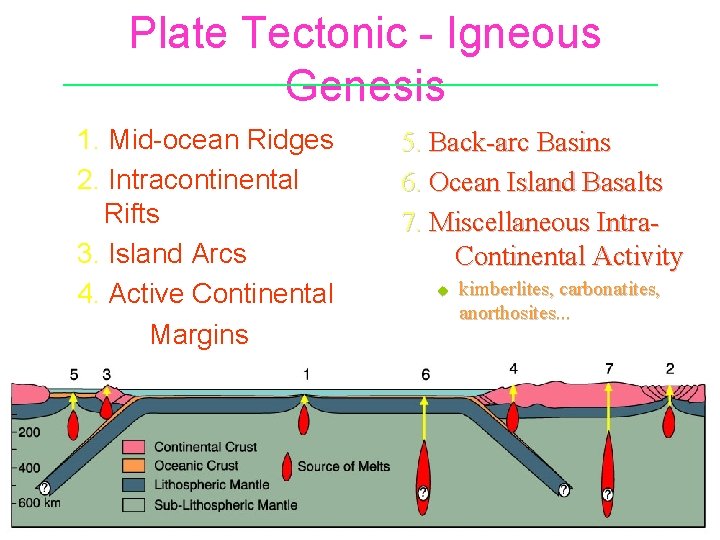

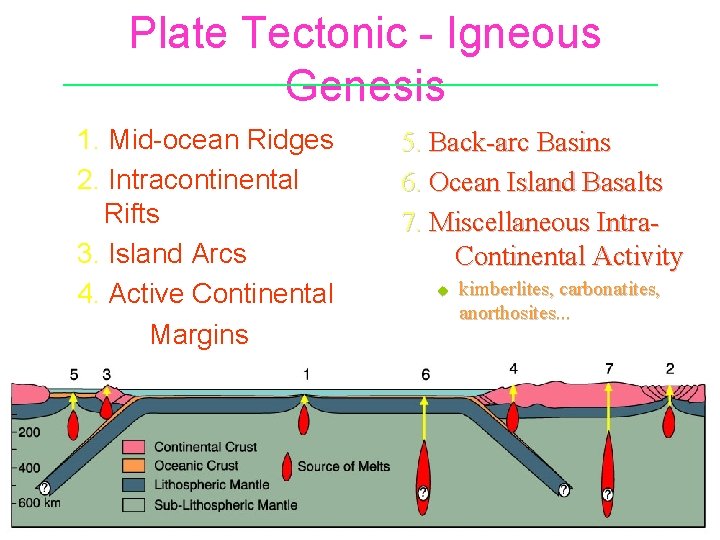

Plate Tectonic - Igneous Genesis 1. Mid-ocean Ridges 2. Intracontinental Rifts 3. Island Arcs 4. Active Continental Margins 5. Back-arc Basins 6. Ocean Island Basalts 7. Miscellaneous Intra. Continental Activity u kimberlites, carbonatites, anorthosites. . .