IEA low carbon transport analysis Technology Roadmap H

IEA low carbon transport analysis Technology Roadmap H 2 & Fuel Cells Pierpaolo Cazzola IEA Asia Pacific Economic Cooperation - Energy Working Group 54 Electric Vehicle and Hydrogen Technology Policy Workshop Wellington, 21 November 2017 © OECD/IEA 2017

Content • Introduction • Hydrogen and fuel cells in transport • Hydrogen and fuel cells for variable renewable power integration • Hydrogen in industry and buildings • Key findings • Key actions for the next ten years • Q&A © OECD/IEA 2017

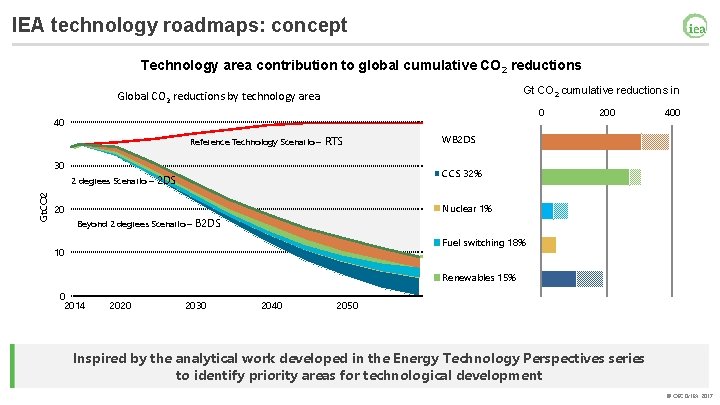

IEA technology roadmaps: concept Technology area contribution to global cumulative CO 2 reductions Gt CO 2 cumulative reductions in Global CO 2 reductions by technology area 0 40 Reference Technology Scenario – RTS 400 WB 2 DS 2 DS 30 2 degrees Scenario – Gt. CO 2 200 32% 0% CCSOther 14% 2 DS CCS 14% Nuclear 6% 1% 20 Beyond 2 degrees Scenario – B 2 DS Nuclear 6% 18% Fuel switching 5% 10 15% Renewables 35% 0 2014 2020 2030 2040 2050 Inspired by the analytical work developed in the Energy Technology Perspectives series to identify priority areas for technological development © OECD/IEA 2017

IEA technology roadmaps: process • Engage cross‐section of stakeholders • Identify a baseline: ‐ Where is the technology today? • Establish a vision: ‐ What is the deployment path needed to achieve 2050 goals? • Identify technical, regulatory, policy, financial and public acceptance barriers • Develop implementation action items for stakeholders © OECD/IEA 2017

Technology Roadmap H 2 & Fuel Cells Key opportunities • Hydrogen is a flexible energy carrier that can generated from several primary energy sources, primarily via steam reforming of methane or electrolysis • Electrolysis is the most promising pathway for the production of low‐carbon hydrogen, as it does not require the use of fuel containing carbon • Hydrogen with a low‐carbon footprint has the potential to facilitate significant reductions in energy‐related CO 2 emissions • As an energy carrier, hydrogen can enable new linkages between energy supply and demand bridge renewable energies into demand sectors, which are difficult to decarbonise, including the transport sector © OECD/IEA 2017

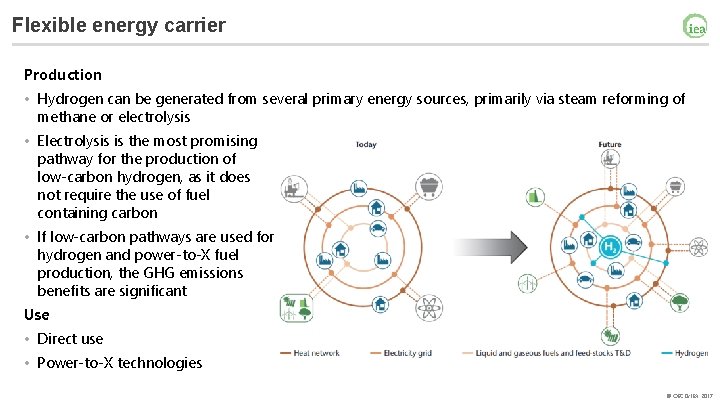

Flexible energy carrier Production • Hydrogen can be generated from several primary energy sources, primarily via steam reforming of methane or electrolysis • Electrolysis is the most promising pathway for the production of low‐carbon hydrogen, as it does not require the use of fuel containing carbon • If low‐carbon pathways are used for hydrogen and power‐to‐X fuel production, the GHG emissions benefits are significant Use • Direct use • Power‐to‐X technologies © OECD/IEA 2017

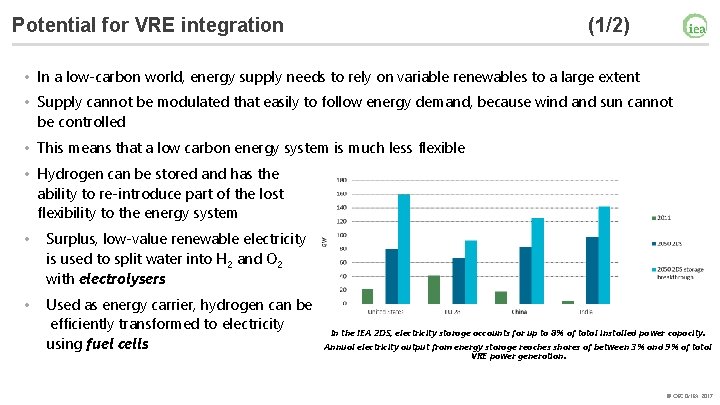

Potential for VRE integration (1/2) • In a low‐carbon world, energy supply needs to rely on variable renewables to a large extent • Supply cannot be modulated that easily to follow energy demand, because wind and sun cannot be controlled • This means that a low carbon energy system is much less flexible • Hydrogen can be stored and has the ability to re‐introduce part of the lost flexibility to the energy system • Surplus, low‐value renewable electricity is used to split water into H 2 and O 2 with electrolysers • Used as energy carrier, hydrogen can be efficiently transformed to electricity using fuel cells In the IEA 2 DS, electricity storage accounts for up to 8% of total installed power capacity. Annual electricity output from energy storage reaches shares of between 3% and 9% of total VRE power generation. © OECD/IEA 2017

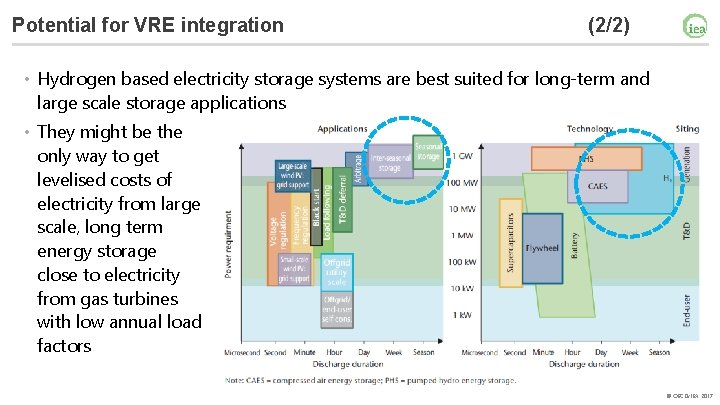

Potential for VRE integration (2/2) • Hydrogen based electricity storage systems are best suited for long‐term and large scale storage applications • They might be the only way to get levelised costs of electricity from large scale, long term energy storage close to electricity from gas turbines with low annual load factors © OECD/IEA 2017

Potential for transport Decarbonising the sector requires: • changing the nature and the structure of transport demand, • major improvements in efficiency, • and rapid transitions in the energy mix used to move people and goods. Decarbonising long‐distance transport modes – in particular aviation, heavy‐duty road transport (i. e. trucking and buses) and shipping – is most challenging • The use of hydrogen in transport can enable long distance, low carbon driving • FCEVs can achieve a mobility service compared to today’s conventional cars at potentially very low WTW carbon emissions • With rapid market uptake and fuel tax exemption of hydrogen, FCEVs could be entirely cost competitive 15 to 20 years after market introduction © OECD/IEA 2017

Potential for other end-uses Energy transformation • Low‐carbon hydrogen can be a mean to reduce upstream emissions in liquid fuel production processes Industry • The more efficient use of hydrogen in the steel industry has the potential to contribute to significant CO 2 emissions reduction • In industry, hydrogen use can play an enabling role for the application of CCS technologies • The use of renewable hydrogen in industry hinges upon its economic competitiveness – in particular when compared to hydrogen from natural gas SMR with CCS Buildings • Natural gas‐fuelled fuel cell micro CHP systems can help increasing the efficiency of buildings but struggle with costs © OECD/IEA 2017

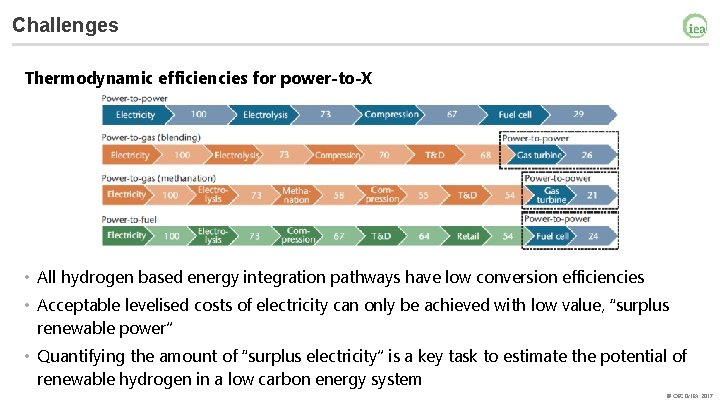

Challenges Current hydrogen production pathways are carbon-intensive • Today, hydrogen is produced and used primarily in the chemical and industrial gas industries: around half from natural gas through steam methane reforming, one‐third as a fraction of petroleum during the refining process, the rest from either coal or electrolysis Costs • Steam methane reforming currently setting the benchmark or costs, low‐carbon hydrogen production more expensive • Fuel cell and hydrogen storage costs are still high Investment risks • Underutilization of infrastructure during market development • Path dependency of solutions • Need for scale to reduce costs, need for lower costs to stimulate demand Thermodynamic losses • Several steps during hydrogen’s production and distribution – including production (via electrolysis or steam reforming), transportation and refuelling © OECD/IEA 2017

Challenges Thermodynamic efficiencies for power-to-X • All hydrogen based energy integration pathways have low conversion efficiencies • Acceptable levelised costs of electricity can only be achieved with low value, “surplus renewable power” • Quantifying the amount of “surplus electricity” is a key task to estimate the potential of renewable hydrogen in a low carbon energy system © OECD/IEA 2017

Solutions/Opportunities Current hydrogen production pathways are carbon-intensive • Falling costs of VRE and need for storage may lead to affordable renewable hydrogen (or power‐to‐X fuels), especially in regions with high VRE endowment Costs • Carbon pricing strengthens the cost competitiveness of low‐carbon hydrogen, and all low carbon IEA scenarios have significant increase of CO 2 prices • There is significant potential to bring down fuel cell costs through high‐volume manufacturing and with next‐generation laboratory technology • Costs can also be reduced for hydrogen storage tanks, buy the potential for cost reduction is lower Investment risks • Captive applications and energy storage can get the process started • The transition to hydrogen needs span across the whole energy system (large volumes, sharing infrastructure costs) Thermodynamic losses • The thermodynamic efficiency of hydrogen production from ranges between 65‐ 80% for most electrolysers, but there is potential for improvement with lab‐scale applications reaching 85‐ 90%. • Steam reforming in large‐scale applications is also more efficient (85% vs. 50% in small scale) © OECD/IEA 2017

Key actions for the next ten years (1/2) • Encourage fuel efficiency and low greenhouse gas emission technologies across all energy sectors through market driven, technology‐ and fuel‐neutral policies • Stimulate investment and early market deployment of hydrogen and fuel cell technologies and their infrastructure • Continue to strengthen and harmonise international codes and standards • Keep up supporting technology progress and innovation by unlocking public and private funds for RD&D for key hydrogen technologies • Improve understanding of regionally specific interactions between different energy sectors © OECD/IEA 2017

Key actions for the next ten years (2/2) • Put the first tens of thousands of FCEVs on the road, along with hydrogen generation, T&D and refueling infrastructure, including at least 500 to 1 000 stations • Engage international stakeholders from relevant industries as well as regional, national and local authorities in developing risk‐ mitigation strategies • Establish regulatory frameworks that remove barriers to grid access for electricity storage as well as for the blending of hydrogen into the natural gas grid • Increase data on resource availability and costs for hydrogen generation and analyse the potential future availability of curtailed electricity for hydrogen production © OECD/IEA 2017

Focus on transport – getting the transition started • RD&D is essential to keep reducing the cost of fuel cells and hydrogen storage tanks, but it needs to be supported by technology deployment and the scale-up of hydrogen production to deliver cost savings from technology learning and economies of scale • The build‐up of sufficient hydrogen refuelling infrastructure is the first prerequisite needed to make the deployment of hydrogen‐powered motor vehicles possible. ‐ Overcoming the barriers that still face hydrogen production and use in road freight transport also calls for co-ordinated effort across stakeholders to build a minimum number of stations, starting in main urban centres and the major axes of the road transport network. ‐ Refuelling infrastructure for captive fleets provides a way to address the underutilisation barrier. Thanks to higher utilisation rates, refuelling stations for captive fleets enable investments in refuelling infrastructure © OECD/IEA 2017

© OECD/IEA 2017

- Slides: 17