IDSA GUIDELINE 2011 Clinical Practice Guideline for the

- Slides: 41

IDSA GUIDELINE 2011 Clinical Practice Guideline for the Use of Antimicrobial Agents in Neutropenic Patients with Cancer Alireza Fatemi

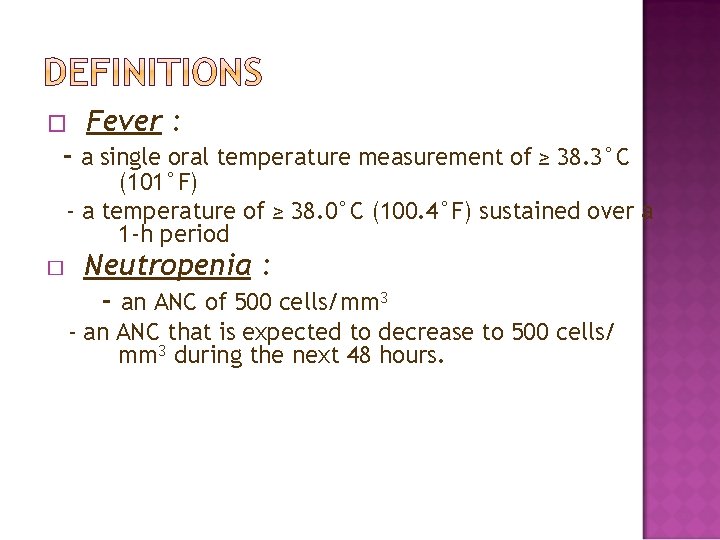

� Fever : - a single oral temperature measurement of ≥ 38. 3°C (101°F) - a temperature of ≥ 38. 0°C (100. 4°F) sustained over a 1 -h period � Neutropenia : - an ANC of 500 cells/mm 3 - an ANC that is expected to decrease to 500 cells/ mm 3 during the next 48 hours.

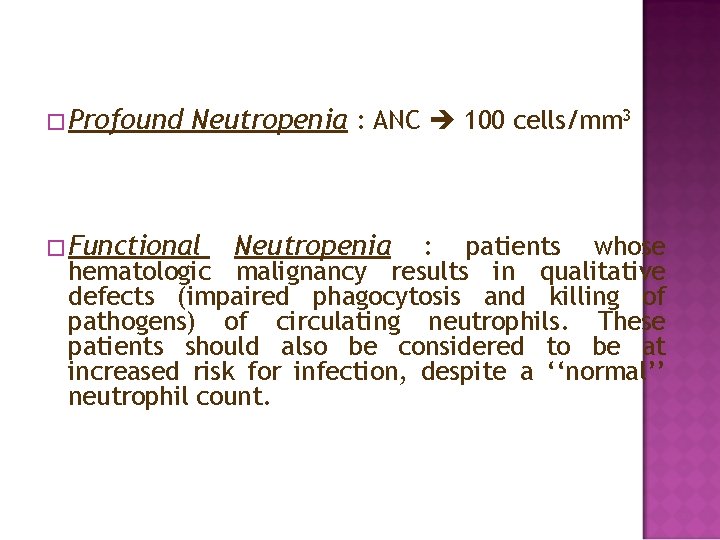

� Profound Neutropenia : ANC 100 cells/mm 3 � Functional Neutropenia : patients whose hematologic malignancy results in qualitative defects (impaired phagocytosis and killing of pathogens) of circulating neutrophils. These patients should also be considered to be at increased risk for infection, despite a ‘‘normal’’ neutrophil count.

� 10%– 50% of patients with solid tumors and >80% of those with hematologic malignancies will develop fever during ≥ 1 chemotherapy cycle associated with neutropenia. � Most patients will have no infectious etiology documented. � Clinically documented infections occur in 20%– 30% of febrile episodes; common sites of tissue-based infection include the intestinal tract, lung, and skin. � Bacteremia occurs in 10%– 25% of all patients, with most episodes occurring in the setting of prolonged or profound neutropenia (ANC, , 100 neutrophils/mm 3).

� Substantial fluctuation in the epidemiologic spectrum of bloodstream isolates obtained from febrile neutropenic patients has occurred over the past 40 years. � Currently, coagulase-negative staphylococci are the most common blood isolates in most centers; Enterobacteriaciae (e. g. , Enterobacter species, Escherichia coli and Klebsiella species) and nonfermenting gram-negative rods (e. g. , Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Stenotrophomonas species) are isolated less often. � Drug-resistant bacteria species are causing an increasing number of infections in febrile neutropenic patients.

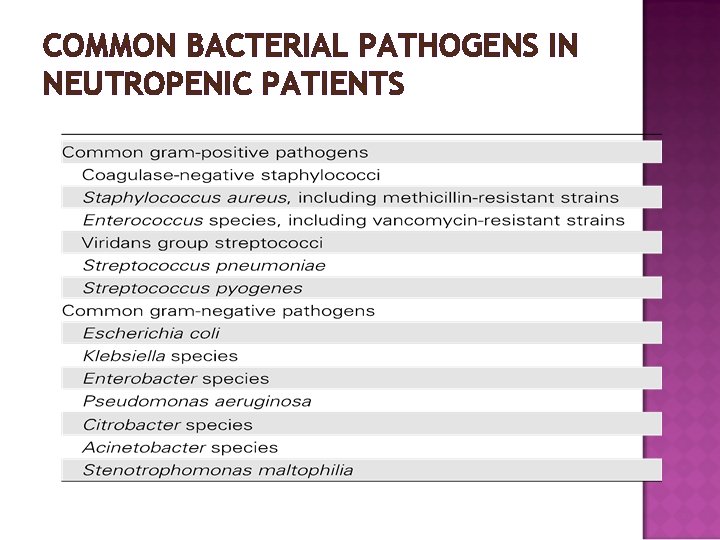

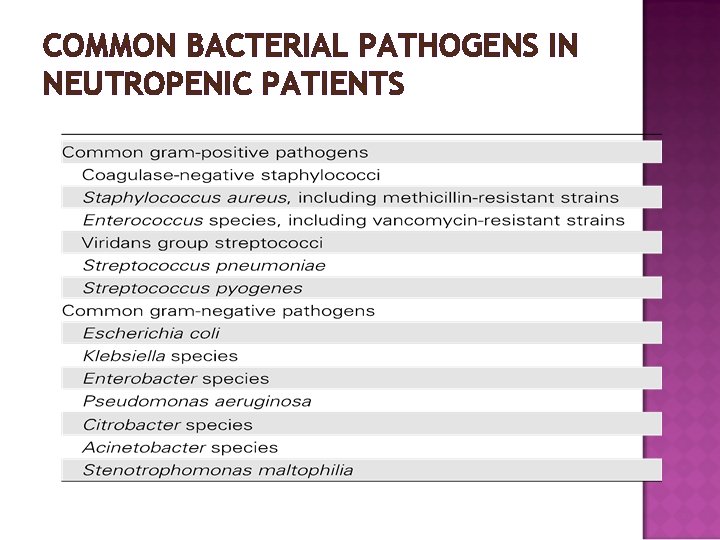

COMMON BACTERIAL PATHOGENS IN NEUTROPENIC PATIENTS

� Fungi are rare. they are encountered after the first week of prolonged neutropenia and empirical antibiotic therapy. � Candida species superficial infections of mucosal surfaces (e. g. , thrush) (chemotherapy- induced mucositis, in turn, may disrupt this barrier). � Deep-tissue candidiasis (hepatic or hepatosplenic disease, esophagitis, or endocarditis), is much less common. � � Molds, such as Aspergillus, are most likely to cause life-threatening infection of the sinuses and lungs, typically after >2 weeks of neutropenia.

- Type of empirical antibiotic therapy (oral or IV) - Venue of treatment (inpatient or outpatient) - Duration of antibiotic therapy

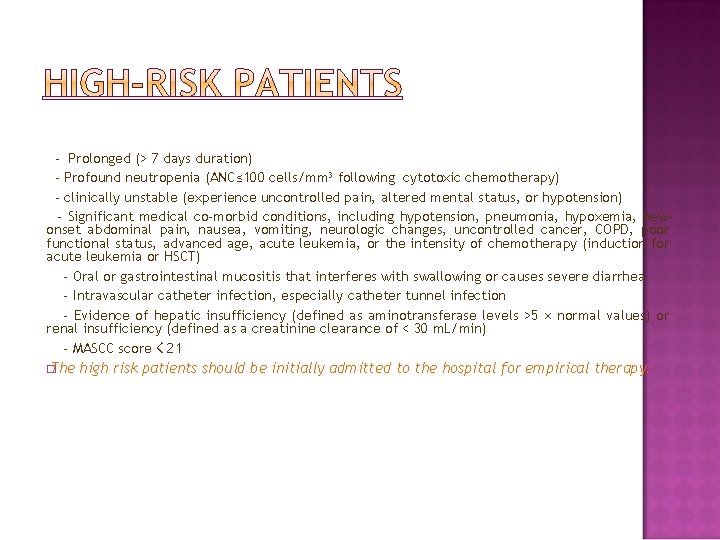

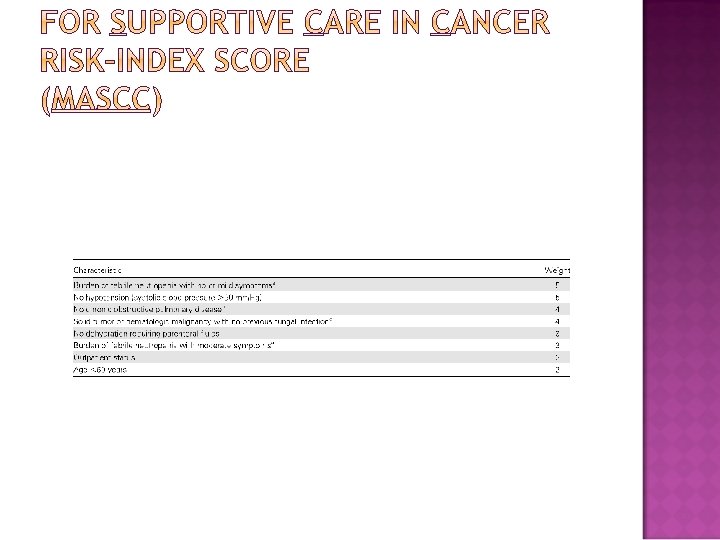

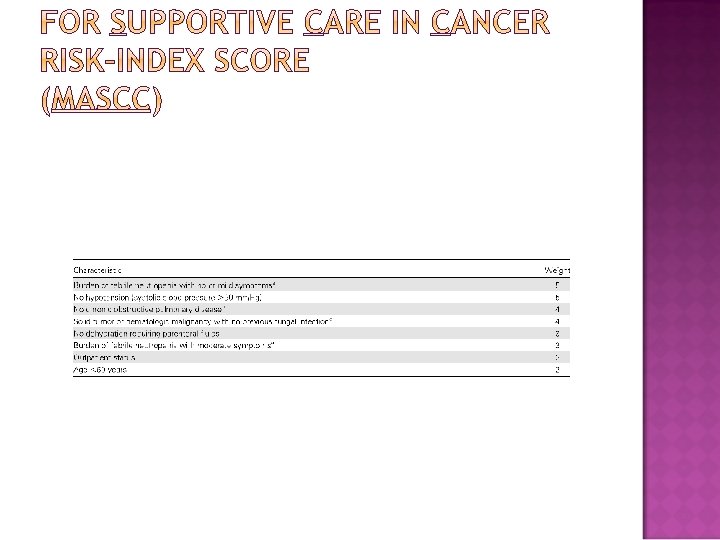

- Prolonged (> 7 days duration) - Profound neutropenia (ANC≤ 100 cells/mm 3 following cytotoxic chemotherapy) - clinically unstable (experience uncontrolled pain, altered mental status, or hypotension) - Significant medical co-morbid conditions, including hypotension, pneumonia, hypoxemia, newonset abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, neurologic changes, uncontrolled cancer, COPD, poor functional status, advanced age, acute leukemia, or the intensity of chemotherapy (induction for acute leukemia or HSCT) - Oral or gastrointestinal mucositis that interferes with swallowing or causes severe diarrhea - Intravascular catheter infection, especially catheter tunnel infection - Evidence of hepatic insufficiency (defined as aminotransferase levels >5 × normal values) or renal insufficiency (defined as a creatinine clearance of < 30 m. L/min) - MASCC score < 21 � The high risk patients should be initially admitted to the hospital for empirical therapy.

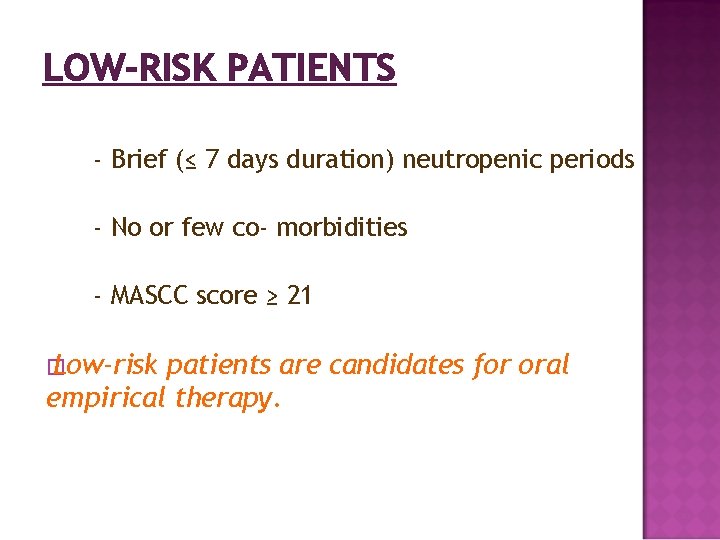

LOW-RISK PATIENTS - Brief (≤ 7 days duration) neutropenic periods - No or few co- morbidities - MASCC score ≥ 21 � Low-risk patients are candidates for oral empirical therapy.

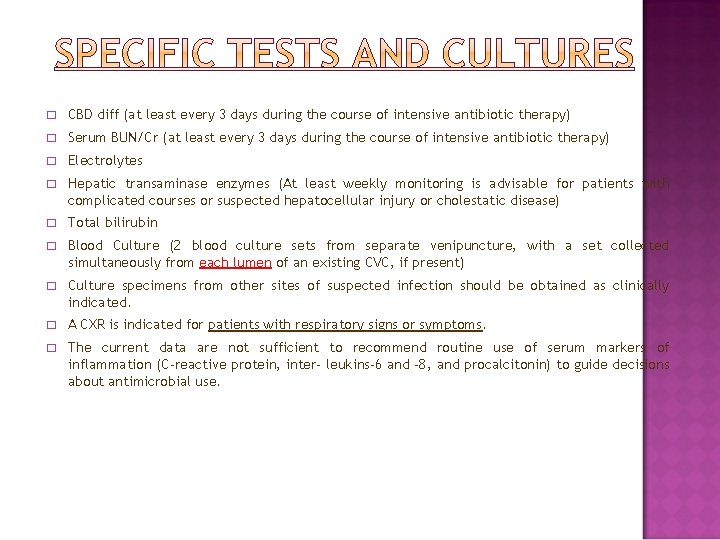

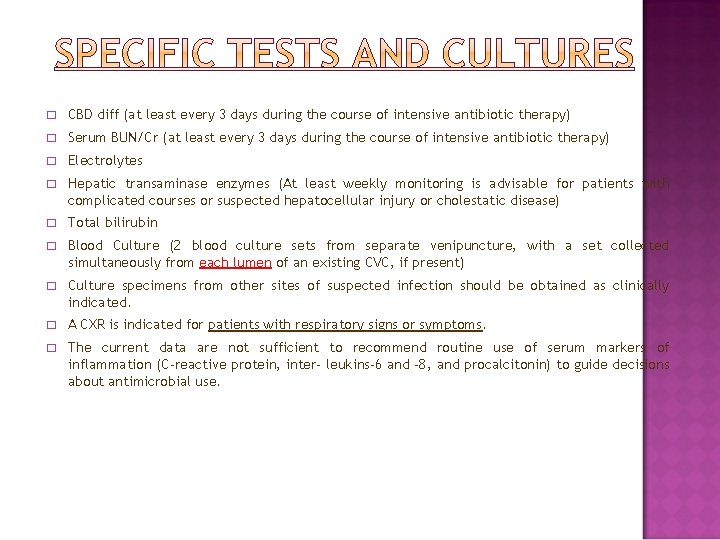

� CBD diff (at least every 3 days during the course of intensive antibiotic therapy) � Serum BUN/Cr (at least every 3 days during the course of intensive antibiotic therapy) � Electrolytes � Hepatic transaminase enzymes (At least weekly monitoring is advisable for patients with complicated courses or suspected hepatocellular injury or cholestatic disease) � Total bilirubin � Blood Culture (2 blood culture sets from separate venipuncture, with a set collected simultaneously from each lumen of an existing CVC, if present) � Culture specimens from other sites of suspected infection should be obtained as clinically indicated. � A CXR is indicated for patients with respiratory signs or symptoms. � The current data are not sufficient to recommend routine use of serum markers of inflammation (C-reactive protein, inter- leukins-6 and -8, and procalcitonin) to guide decisions about antimicrobial use.

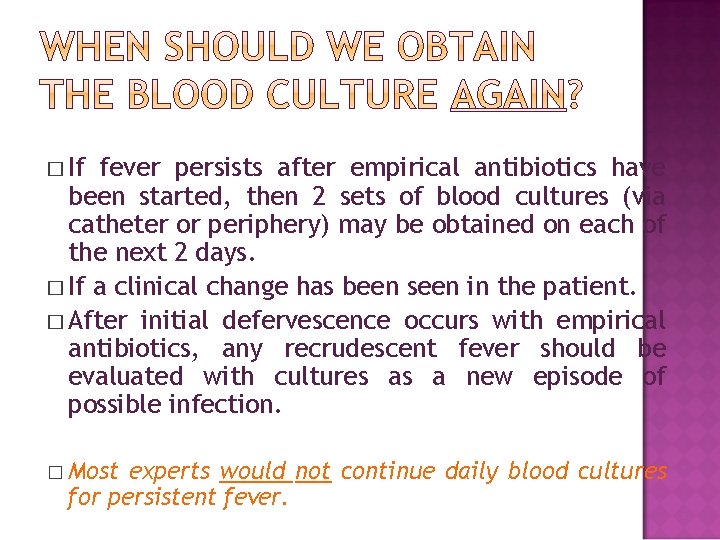

� If fever persists after empirical antibiotics have been started, then 2 sets of blood cultures (via catheter or periphery) may be obtained on each of the next 2 days. � If a clinical change has been seen in the patient. � After initial defervescence occurs with empirical antibiotics, any recrudescent fever should be evaluated with cultures as a new episode of possible infection. � Most experts would not continue daily blood cultures for persistent fever.

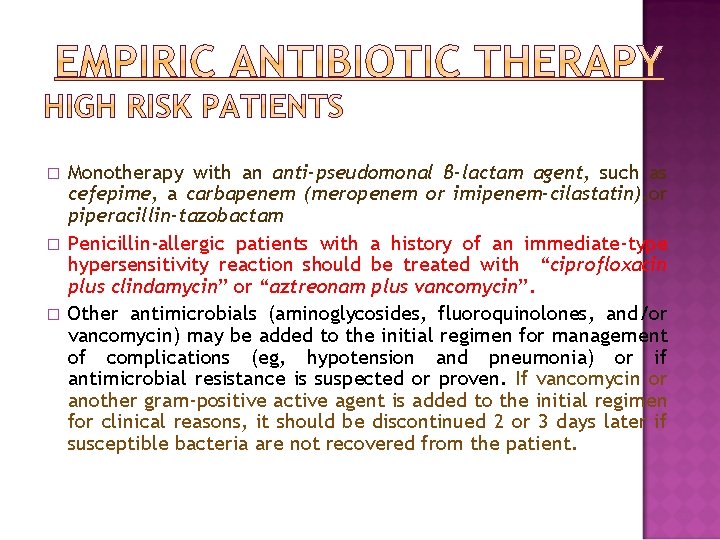

� � � Monotherapy with an anti-pseudomonal β-lactam agent, such as cefepime, a carbapenem (meropenem or imipenem-cilastatin), or piperacillin-tazobactam Penicillin-allergic patients with a history of an immediate-type hypersensitivity reaction should be treated with “ciprofloxacin plus clindamycin” or “aztreonam plus vancomycin”. Other antimicrobials (aminoglycosides, fluoroquinolones, and/or vancomycin) may be added to the initial regimen for management of complications (eg, hypotension and pneumonia) or if antimicrobial resistance is suspected or proven. If vancomycin or another gram-positive active agent is added to the initial regimen for clinical reasons, it should be discontinued 2 or 3 days later if susceptible bacteria are not recovered from the patient.

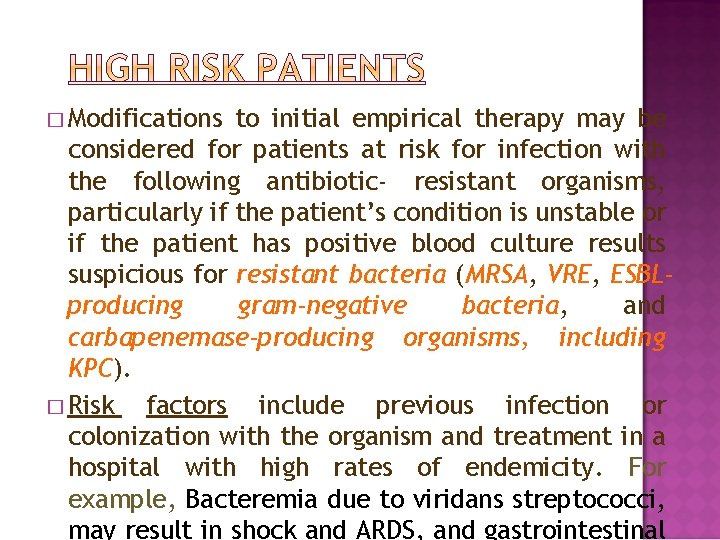

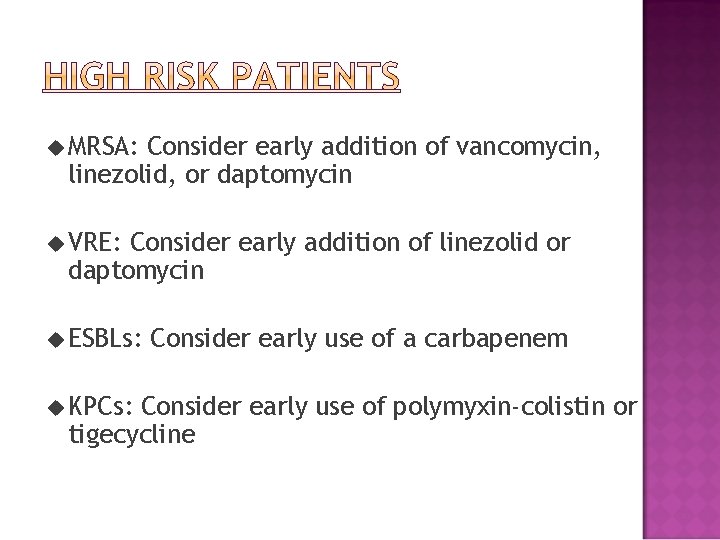

� Modifications to initial empirical therapy may be considered for patients at risk for infection with the following antibiotic- resistant organisms, particularly if the patient’s condition is unstable or if the patient has positive blood culture results suspicious for resistant bacteria (MRSA, VRE, ESBLproducing gram-negative bacteria, and carbapenemase-producing organisms, including KPC). � Risk factors include previous infection or colonization with the organism and treatment in a hospital with high rates of endemicity. For example, Bacteremia due to viridans streptococci, may result in shock and ARDS, and gastrointestinal

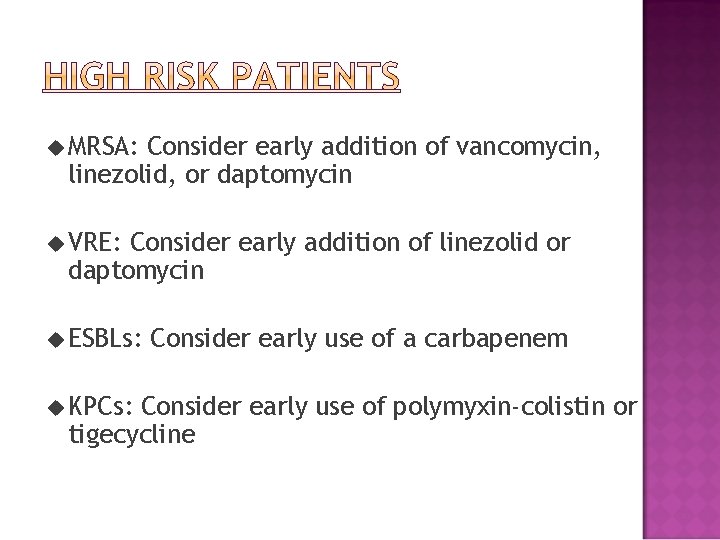

u MRSA: Consider early addition of vancomycin, linezolid, or daptomycin u VRE: Consider early addition of linezolid or daptomycin u ESBLs: u KPCs: Consider early use of a carbapenem Consider early use of polymyxin-colistin or tigecycline

Afebrile neutropenic patients who have new signs or symptoms suggestive of infection should be evaluated and treated as high-risk patients.

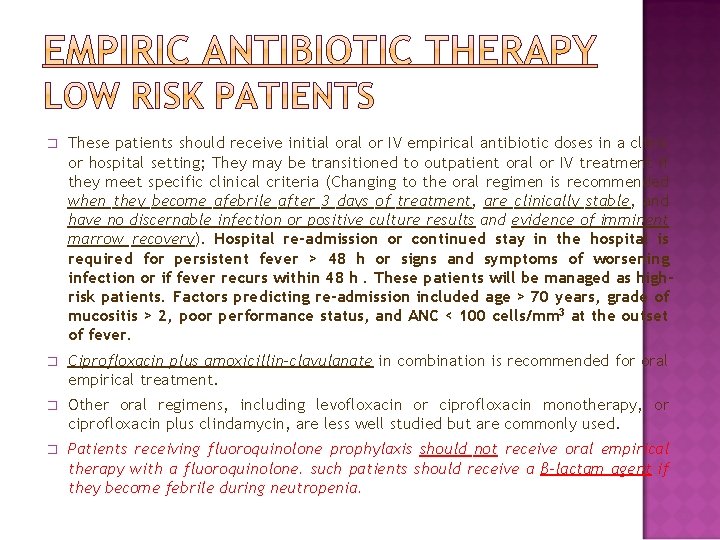

� These patients should receive initial or IV empirical antibiotic doses in a clinic or hospital setting; They may be transitioned to outpatient oral or IV treatment if they meet specific clinical criteria (Changing to the oral regimen is recommended when they become afebrile after 3 days of treatment, are clinically stable, and have no discernable infection or positive culture results and evidence of imminent marrow recovery). Hospital re-admission or continued stay in the hospital is required for persistent fever > 48 h or signs and symptoms of worsening infection or if fever recurs within 48 h. These patients will be managed as highrisk patients. Factors predicting re-admission included age > 70 years, grade of mucositis > 2, poor performance status, and ANC < 100 cells/mm 3 at the outset of fever. � Ciprofloxacin plus amoxicillin-clavulanate in combination is recommended for oral empirical treatment. � Other oral regimens, including levofloxacin or ciprofloxacin monotherapy, or ciprofloxacin plus clindamycin, are less well studied but are commonly used. � Patients receiving fluoroquinolone prophylaxis should not receive oral empirical therapy with a fluoroquinolone. such patients should receive a β-lactam agent if they become febrile during neutropenia.

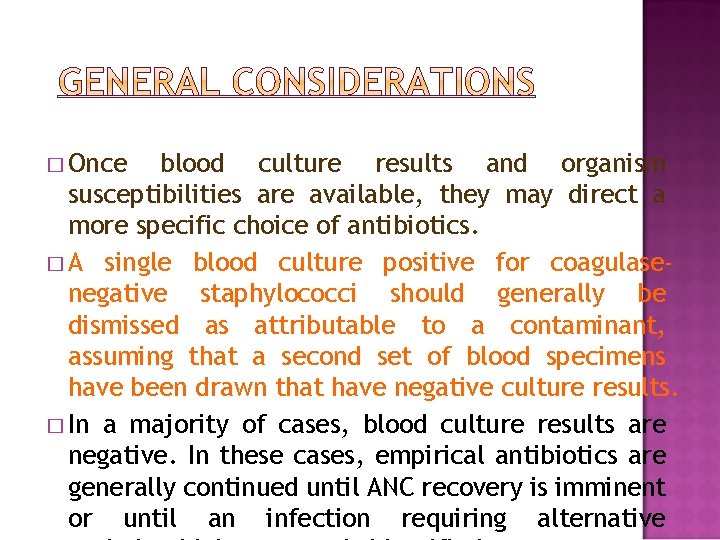

� Once blood culture results and organism susceptibilities are available, they may direct a more specific choice of antibiotics. � A single blood culture positive for coagulasenegative staphylococci should generally be dismissed as attributable to a contaminant, assuming that a second set of blood specimens have been drawn that have negative culture results. � In a majority of cases, blood culture results are negative. In these cases, empirical antibiotics are generally continued until ANC recovery is imminent or until an infection requiring alternative

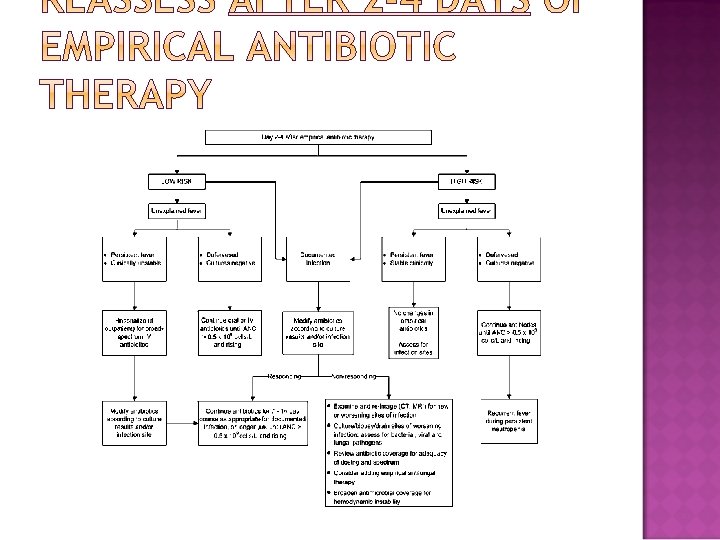

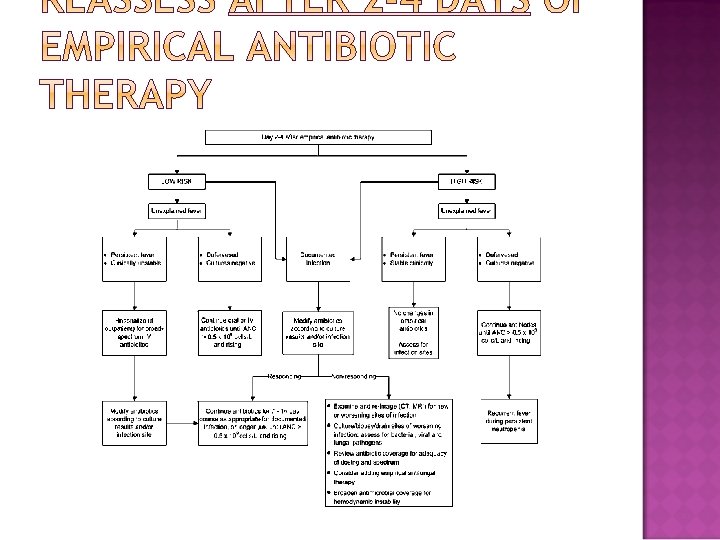

Modifications to the initial antibiotic regimen should be guided by clinical and microbiologic data. If vancomycin or other coverage for gram-positive organisms was started initially, it may be stopped after 2 days if there is no evidence for a grampositive infection. Patients with unexplained fever who are responding to initial empirical therapy may be maintained on that initial regimen until the recovery of ANC to > 500 cells/mm 3. If they have initiated IV antibiotics, patients who meet criteria for being at low risk and can tolerate oral medications may be candidates for transitioning to combination oral antibiotics. Unexplained persistent fever in a patient whose condition is otherwise stable rarely requires an empirical change to the initial antibiotic regimen. If an infection is identified, antibiotics should be adjusted accordingly.

� Recurrent or persistent fever >3 days in duration despite empirical antibiotic therapy should prompt a thorough search for a source of infection, including a new set of blood cultures and symptom-direction collection of other diagnostic tests. Diarrhea should be assessed by analyzing a stool sample for C. difficile toxin. An abdominal CT (in patients with abdominal pain ± diarrhea) to evaluate neutropenic enterocolitis and a CT of the chest and sinuses is recommended for highrisk patients, to further assess for occult invasive fungal infection. � There is no proven advantage to adding vancomycin empirically in the setting of persistent or recrudescent fever and neutropenia. � For patients with recurrent or persistent fever, consideration should also be given to noninfectious sources, such as drug- related fever, thrombophlebitis, the underlying cancer itself, or resorption of blood from a large hematoma.

� Patients who remain hemodynamically unstable after initial doses with standard agents for neutropenic fever should have their antimicrobial regimen broadened to include coverage for resistant gram-negative, grampositive, and anaerobic bacteria (change from an initial cephalosporin to an anti-pseudomonal carbapenem, such as imipenem or meropenem, or addition of an aminoglycoside, ciprofloxacin, or aztreonam together with vancomycin), and fungi (fluconazole or a newer antifungal agent , if fluconazole is already being given prophylactically).

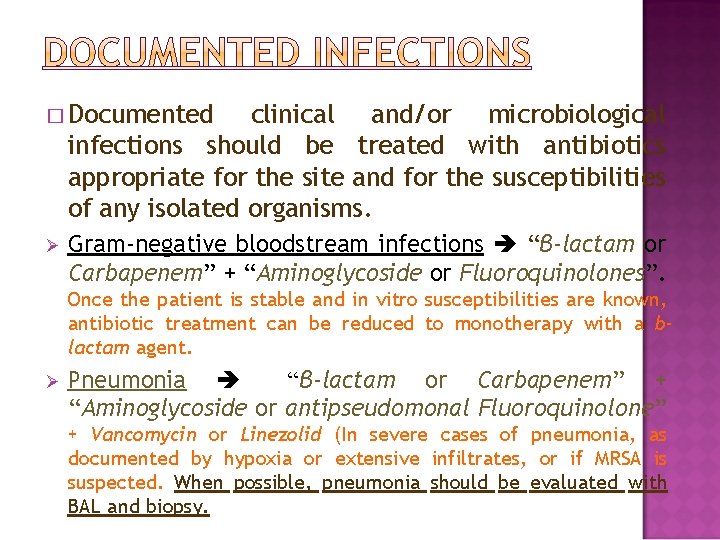

� Documented clinical and/or microbiological infections should be treated with antibiotics appropriate for the site and for the susceptibilities of any isolated organisms. Ø Gram-negative bloodstream infections “β-lactam or Carbapenem” + “Aminoglycoside or Fluoroquinolones”. Once the patient is stable and in vitro susceptibilities are known, antibiotic treatment can be reduced to monotherapy with a blactam agent. Ø Pneumonia “β-lactam or Carbapenem” + “Aminoglycoside or antipseudomonal Fluoroquinolone” + Vancomycin or Linezolid (In severe cases of pneumonia, as documented by hypoxia or extensive infiltrates, or if MRSA is suspected. When possible, pneumonia should be evaluated with BAL and biopsy.

Ø Gram-positive bloodstream isolates or skin and softtissue infections early addition of Vancomycin (or Linezolid or Daptomycin) Ø Oral ulcerations or symptoms of esophagitis HSV or Candida esophagitis acyclovir ± fluconazole Ø Neutropenic enterocolitis ‘‘typhlitis’’ (abdominal pain ((RLQ)) CT of abdomen + Piperacillin/Tazobactam or Carbapenem or a combination of an antipseudomonal Cephalosporin plus Metronidazole. These patients should be evaluated by a surgeon in case a bowel resection is required for uncontrolled sepsis, bleeding, or ischemic bowel.

� � � In patients with clinically or microbiologically documented infections, the duration of therapy is dictated by the particular organism and site; appropriate antibiotics should continue for at least the duration of neutropenia (until ANC ≥ 500 cells/mm 3) or longer if clinically necessary. In patients with unexplained fever, it is recommended that the initial regimen be continued until there are clear signs of marrow recovery; the traditional endpoint is an increasing ANC that exceeds 500 cells/mm 3. Alternatively, if an appropriate treatment course has been completed and all signs and symptoms of a documented infection have resolved, patients who remain neutropenic may resume oral fluoroquinolone prophylaxis until marrow recovery.

Ø Most bacterial bloodstream infections, soft-tissue infections, and pneumonias require 10– 14 days of appropriate antibiotic therapy. Antibiotic treatment may therefore extend beyond resolution of fever and neutropenia. In the absence of significant impairment of gastrointestinal function, an oral antibiotic regimen may be undertaken to complete the full course of therapy.

� Fluoroquinolone (Ciprofloxacin or Levofloxacin) High-risk patients with expected durations of prolonged and profound neutropenia (ANC ≤ 100 cells/mm 3 for > 7 days) � Levofloxacin is preferred in situations with increased risk for oral mucositis-related invasive viridans group streptococcal infection. � Antibacterial prophylaxis is not routinely recommended for low-risk patients who are anticipated to remain neutropenic for < 7 days. � The question of when to initiate and discontinue antibacterial chemoprophylaxis has not been systematically studied.

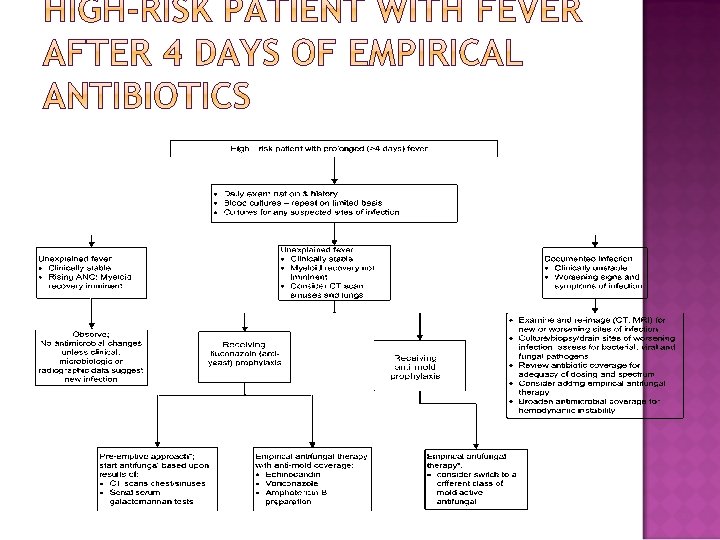

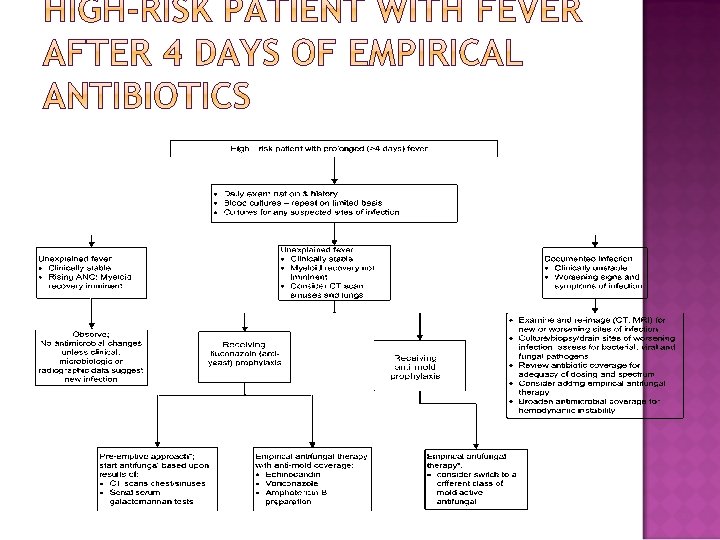

� Empirical antifungal therapy and investigation for invasive fungal infections Persistent or recurrent fever after 4– 7 days of antibiotics and whose overall duration of neutropenia is expected to be > 7 days. � Preemptive antifungal management Antifungal therapy should be instituted if any of these indicators of possible invasive fungal infection(clinically unstable, have any clinical or chest and sinus CT signs of fungal infection (Macronodules ± halo sign), have positive serologic assay results for evidence of invasive fungal infection (Serial β-(1 -3)-D glucan test and galactomannan test), and have any recovery of fungi , such as Candida or Aspergillus species, from any body site)are identified. This approach currently remains largely experimental and is not standard of practice. � If the patient is receiving mold-active prophylaxis (Itraconazole or Posaconazole), in the absence of changes visible on CT, and if serum levels of anti-mold azole prophylaxis are adequate, continuing the same mold-active prophylaxis may be an acceptable alternative.

� � The β-(1 -3)-D glucan test detects most of the relevant fungal pathogens, including Candida species, Aspergillus species, Pneumocystis species, and Fusarium species (but not the zygomycetes agents or Cryptococcus species). Hemodialysis, hemolysis, serum turbidity, hyperlipidemia, visible bilirubin, use of blood products including immunoglobulin and albumin, bacteremia, and the specimen’s exposure to gauze may confound interpretation of the test. The Serum/BAL Galactomannan assay detects only Aspergillus species, Penicillium species, and Histoplasma capsulatum and does not detect other pathogenic fungi. The performance of the galactomannan assay may be confounded by concomitant use of βlactam/β-lactamase combinations, such as piperacillintazobactam (false positives) or anti-mold antifungal agents (false negatives).

� In these patients, the risk of invasive fungal infection is low, and therefore routine use of empirical antifungal therapy is not recommended.

� Prophylaxis against Candida infections is recommended in patient groups in whom the risk of invasive candidal infections is substantial, such as allogeneic HSCT recipients (at least 75 days after transplant, or until cessation of immunosuppressive therapy) or those undergoing intensive remission-induction or salvage induction chemotherapy for acute leukemia. Fluconazole, Itraconazole, Voriconazole, Posaconazole, Micafungin, and Caspofungin are all acceptable alternatives. � Prophylaxis against invasive Aspergillus infections with Posaconazole should be considered for selected patients ≥ 13 years of age who are undergoing intensive chemotherapy for AML/MDS in whom the risk of invasive aspergillosis without prophylaxis is substantial. � Prophylaxis against Aspergillus infection in preengraftment allogeneic or autologous transplant recipients has not been shown to be efficacious. However, a mold-active agent is recommended in patients with prior invasive aspergillosis, anticipated prolonged neutropenic periods of at least 2 weeks, or a prolonged period of neutropenia immediately prior to HSCT.

Antifungal prophylaxis is not recommended for patients in whom the anticipated duration of neutropenia is < 7 days.

HSV-seropositive patients undergoing allogeneic or autologous HSCT or leukemia induction therapy should receive acyclovir antiviral prophylaxis. Antiviral treatment for HSV or VZV is only indicated if there is clinical or laboratory evidence of active viral disease. Respiratory virus testing (including testing for influenza, Parainfluenza, Adenovirus, RSV, and Human metapneumovirus) and chest radiography are indicated for patients with upper respiratory symptoms (eg, coryza) and/or cough. Routine treatment of RSV infection in neutropenic patients with upper respiratory disease should not be given. Yearly influenza vaccination with inactivated vaccine is recommended for all patients being treated for cancer and their household contacts. Serologic responses may be best between chemotherapy cycles (>7 days after the last treatment) or >2 weeks before chemotherapy starts. In the setting of an influenza exposure or outbreak, neutropenic patients presenting with influenza-like illness should receive treatment empirically.

� Prophylactic use of myeloid CSFs should be considered for patients in whom the anticipated risk of fever and neutropenia is ≥ 20%. � CSFs are not generally recommended for treatment of established fever and neutropenia.

� DTP>120 min of qualitative blood cultures performed on specimens simultaneously drawn from the CVC and a vein suggests a CLABSI. � For CLABSI caused by S. aureus, P. aeruginosa, fungi, or mycobacteria, catheter removal is recommended in addition to systemic antimicrobial therapy for at least 14 days. � Catheter removal is also recommended for tunnel infection or port pocket site infection, septic thrombosis, endocarditis, sepsis with hemodynamic instability, or bloodstream infection that persists despite > 72 h of therapy with appropriate antibiotics. � For documented CLABSI caused by coagulase-negative staphylococci, the catheter may be retained using systemic therapy with or without antibiotic lock therapy. � Prolonged treatment (4– 6 weeks) is recommended for complicated CLABSI, defined as the presence of deep tissue infection, endocarditis, septic thrombosis, or persistent bacteremia or fungemia occurring >72 h after catheter removal in a patient who has received appropriate antimicrobials.

Hand hygiene, maximal sterile barrier precautions, and cutaneous antisepsis with chlorhexidine during CVC insertion are recommended for all CVC insertions.

Hand hygiene is the most effective means of preventing transmission of infection in the hospital. Standard barrier precautions should be followed for all patients, and infection-specific isolation should be used for patients with certain signs or symptoms. HSCT recipients should be placed in private (i. e. , single-patient) rooms. Allogeneic HSCT recipients should be placed in rooms with >12 air exchanges/h and HEPA filtration. Plants and dried or fresh flowers should not be allowed in the rooms of hospitalized neutropenic patients. Hospital work exclusion policies should be designed to encourage HCWs to report their illnesses or exposures. Vaccination of HCWs and visitors, including annual influenza, measles, mumps, rubella, and varicella vaccination (if indicated), are recommended.