Identifying Online Learning Communities with Social Network Analysis

- Slides: 28

Identifying Online Learning Communities with Social Network Analysis: Implications for Learning Design & Facilitation Shazia K. Jan Director Learning & Teaching, Faculty of Business & Economics

Presentation Outline 1. Background 2. Integrated Methodological Framework (IMF) 3. Case Studies 4. Conclusion

Background 3

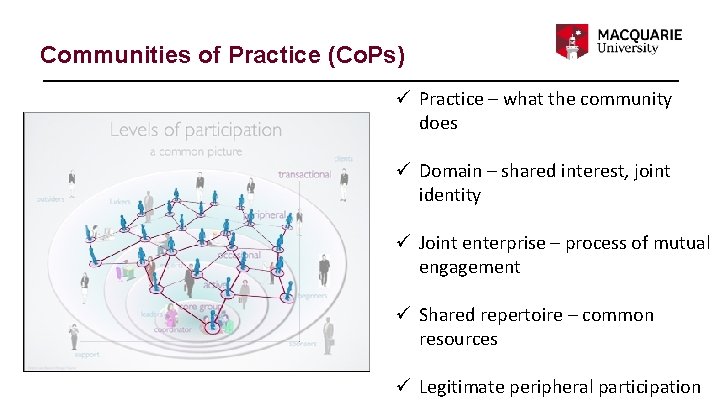

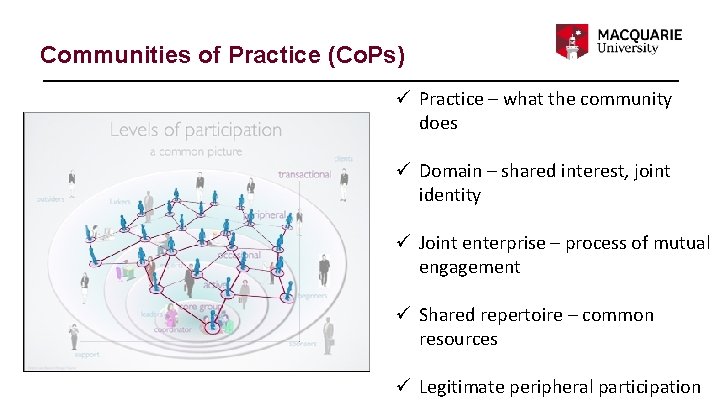

Communities of Practice (Co. Ps) ü Practice – what the community does ü Domain – shared interest, joint identity ü Joint enterprise – process of mutual engagement ü Shared repertoire – common resources ü Legitimate peripheral participation

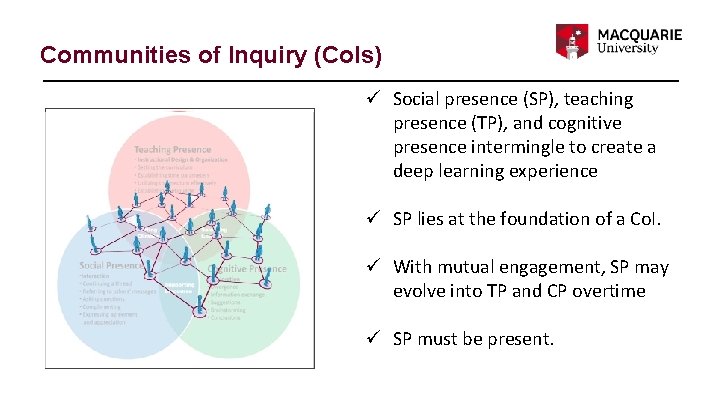

Communities of Inquiry (Co. Is) ü Social presence (SP), teaching presence (TP), and cognitive presence intermingle to create a deep learning experience ü SP lies at the foundation of a Co. I. ü With mutual engagement, SP may evolve into TP and CP overtime ü SP must be present.

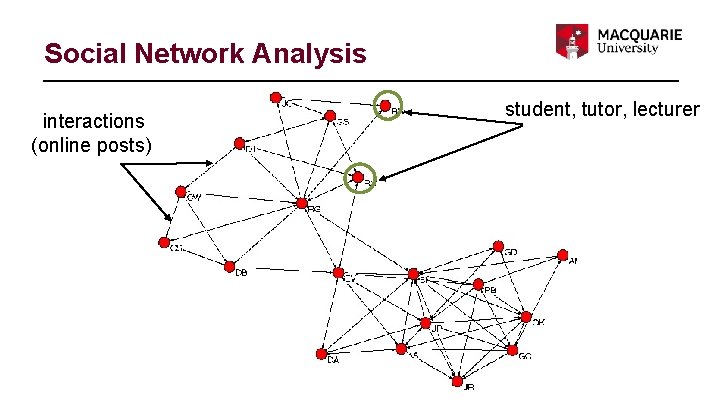

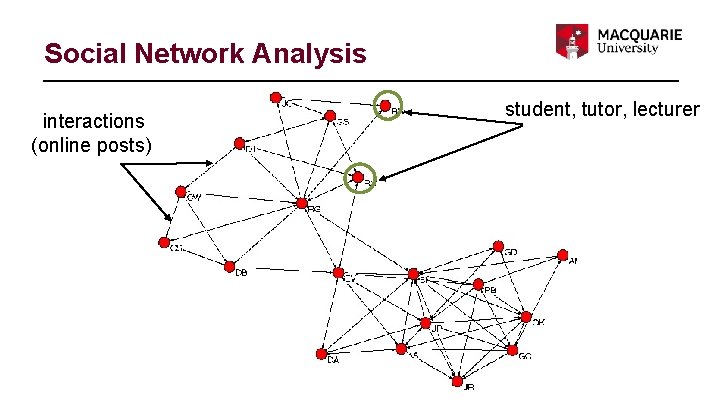

Social Network Analysis interactions (online posts) student, tutor, lecturer

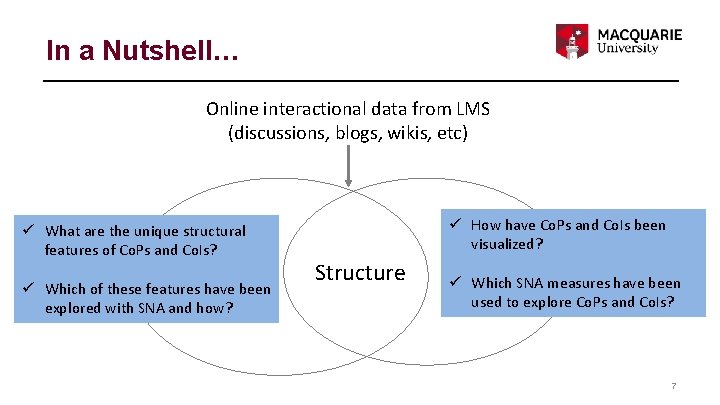

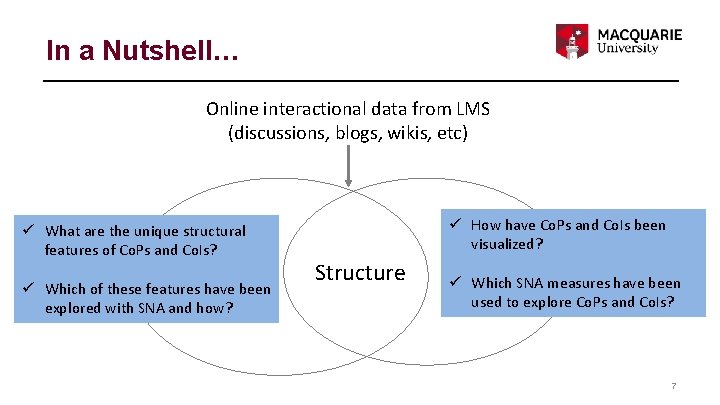

In a Nutshell… Online interactional data from LMS (discussions, blogs, wikis, etc) ü What are the unique structural features of Co. Ps and Co. Is? Co. Ps & Co. Is ü Which of these features have been explored with SNA and how? ü How have Co. Ps and Co. Is been Social visualized? Structure Network ü Which SNA measures have been Analysis used to explore Co. Ps and Co. Is? 7

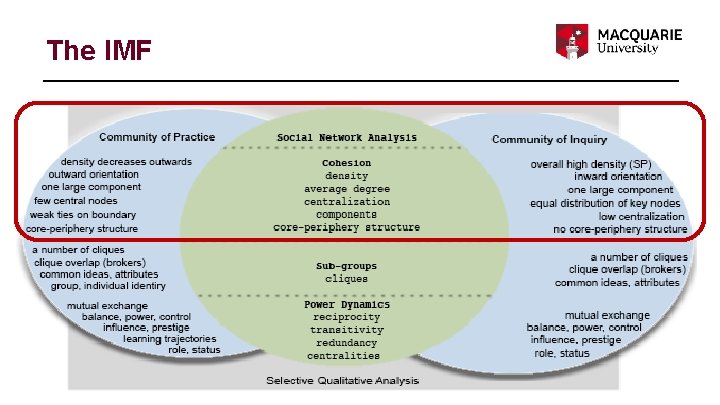

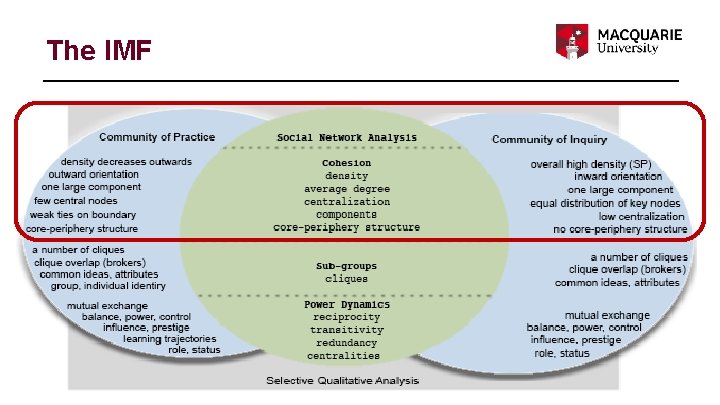

The IMF

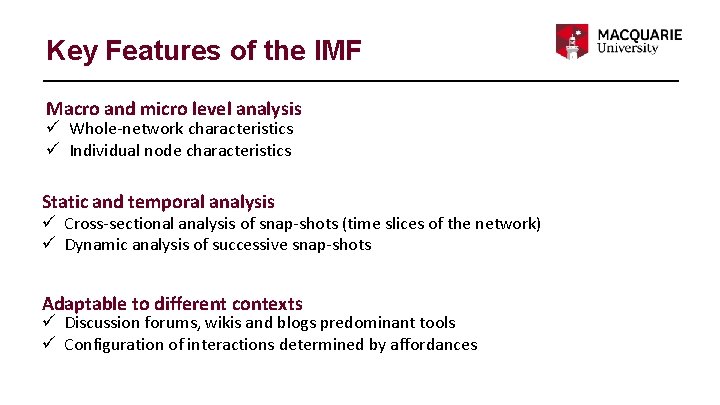

Key Features of the IMF Macro and micro level analysis ü Whole-network characteristics ü Individual node characteristics Static and temporal analysis ü Cross-sectional analysis of snap-shots (time slices of the network) ü Dynamic analysis of successive snap-shots Adaptable to different contexts ü Discussion forums, wikis and blogs predominant tools ü Configuration of interactions determined by affordances

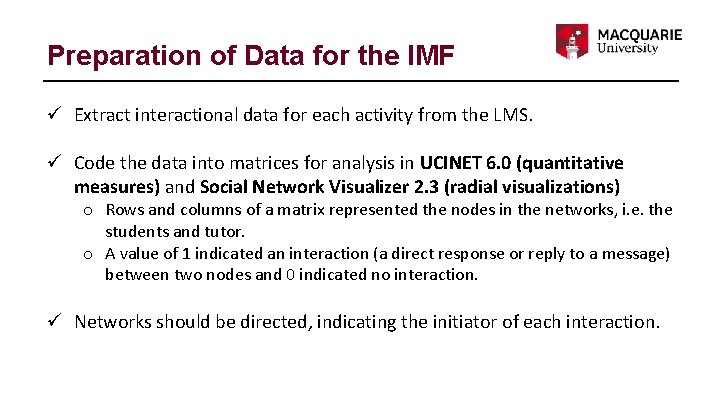

Preparation of Data for the IMF ü Extract interactional data for each activity from the LMS. ü Code the data into matrices for analysis in UCINET 6. 0 (quantitative measures) and Social Network Visualizer 2. 3 (radial visualizations) o Rows and columns of a matrix represented the nodes in the networks, i. e. the students and tutor. o A value of 1 indicated an interaction (a direct response or reply to a message) between two nodes and 0 indicated no interaction. ü Networks should be directed, indicating the initiator of each interaction.

Case Study 1 ü Fully online B. A. course in Health Sciences at a European University ü Students = 20 (practicing healthcare professionals) ü Tutor = 1 (subject expert) 3 weeks Discussion 1 Guided and facilitated by the subject expert, the tutor. 3 weeks Discussion 2 Students discussed a practice online, e. g. , something they did in the hospital. 3 weeks Discussion 3 Free-flowing - students could raise anything they wished in relation to the course or their practice.

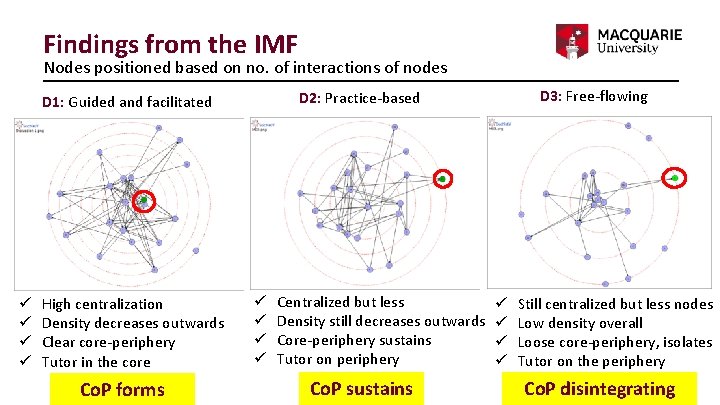

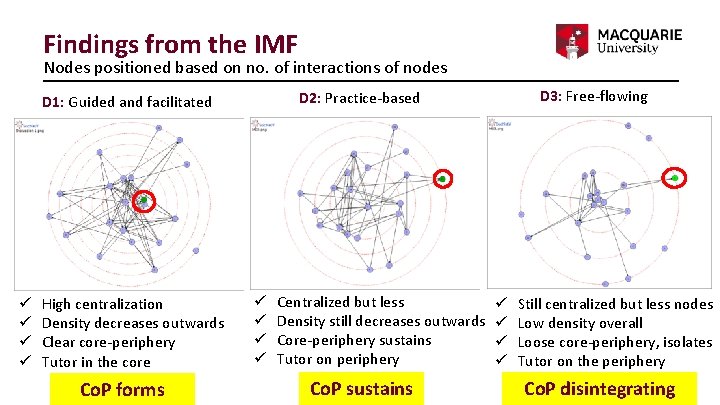

Findings from the IMF Nodes positioned based on no. of interactions of nodes ü ü High centralization Density decreases outwards Clear core-periphery Tutor in the core Co. P forms D 3: Free-flowing D 2: Practice-based D 1: Guided and facilitated ü ü Centralized but less Density still decreases outwards Core-periphery sustains Tutor on periphery Co. P sustains ü ü Still centralized but less nodes Low density overall Loose core-periphery, isolates Tutor on the periphery Co. P disintegrating

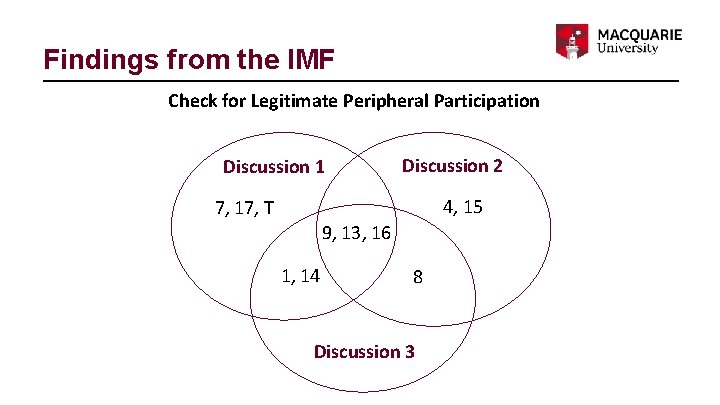

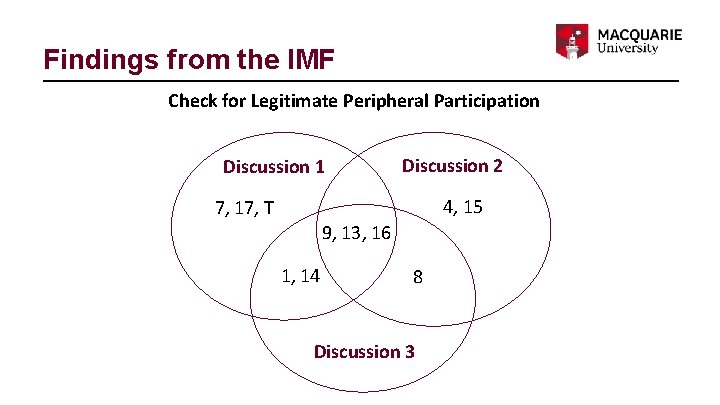

Findings from the IMF Check for Legitimate Peripheral Participation Discussion 1 Discussion 2 4, 15 7, 17, T 9, 13, 16 1, 14 8 Discussion 3

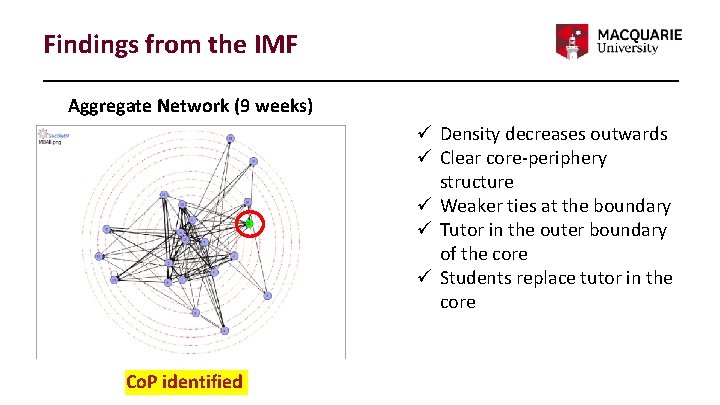

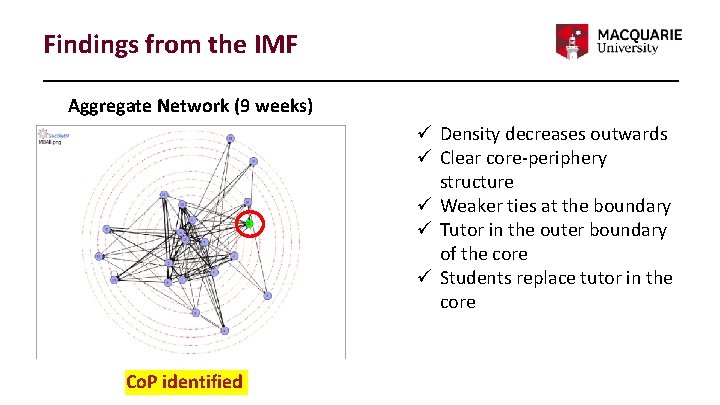

Findings from the IMF Aggregate Network (9 weeks) ü Density decreases outwards ü Clear core-periphery structure ü Weaker ties at the boundary ü Tutor in the outer boundary of the core ü Students replace tutor in the core Co. P identified

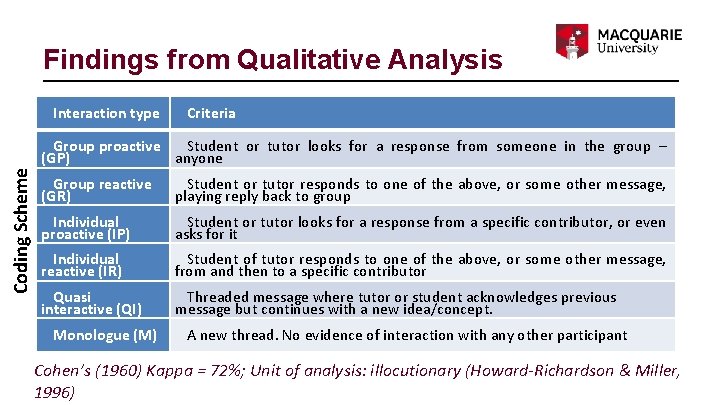

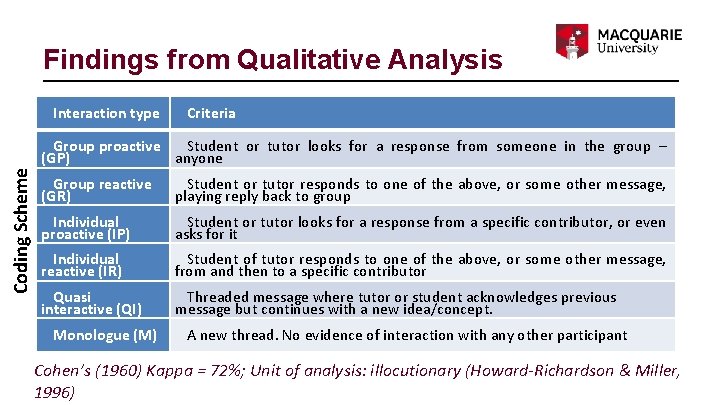

Findings from Qualitative Analysis Interaction type Criteria Coding Scheme Group proactive Student or tutor looks for a response from someone in the group – (GP) anyone Group reactive (GR) Student or tutor responds to one of the above, or some other message, playing reply back to group Individual proactive (IP) Student or tutor looks for a response from a specific contributor, or even asks for it Individual reactive (IR) Student of tutor responds to one of the above, or some other message, from and then to a specific contributor Quasi interactive (QI) Threaded message where tutor or student acknowledges previous message but continues with a new idea/concept. Monologue (M) A new thread. No evidence of interaction with any other participant Cohen’s (1960) Kappa = 72%; Unit of analysis: illocutionary (Howard-Richardson & Miller, 1996)

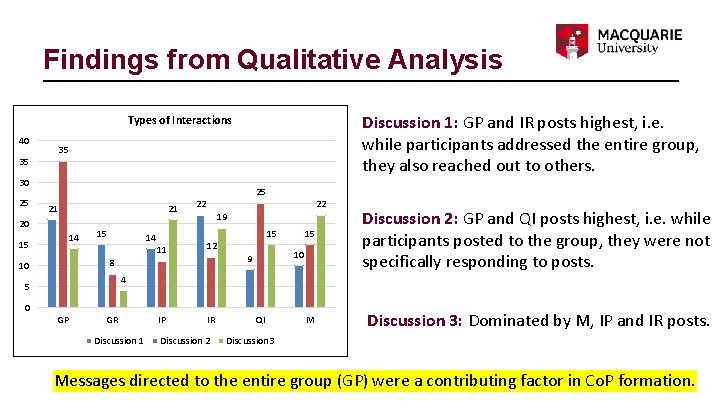

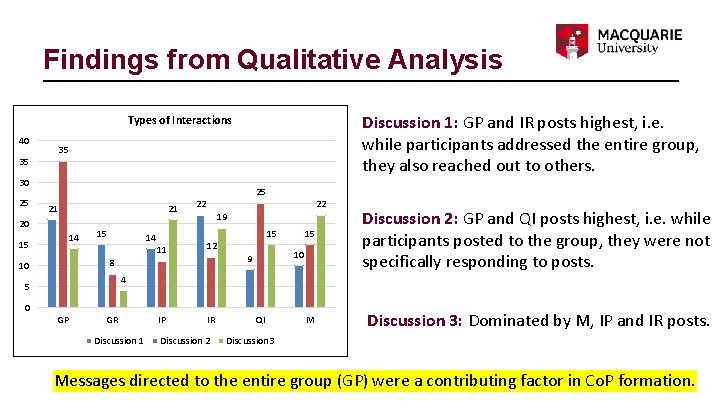

Findings from Qualitative Analysis Discussion 1: GP and IR posts highest, i. e. while participants addressed the entire group, they also reached out to others. Types of Interactions 40 35 35 30 25 25 21 21 20 14 15 15 22 22 19 15 14 11 12 10 IP IR 10 9 8 15 Discussion 2: GP and QI posts highest, i. e. while participants posted to the group, they were not specifically responding to posts. 4 5 0 GP GR Discussion 1 Discussion 2 QI M Discussion 3: Dominated by M, IP and IR posts. Discussion 3 Messages directed to the entire group (GP) were a contributing factor in Co. P formation.

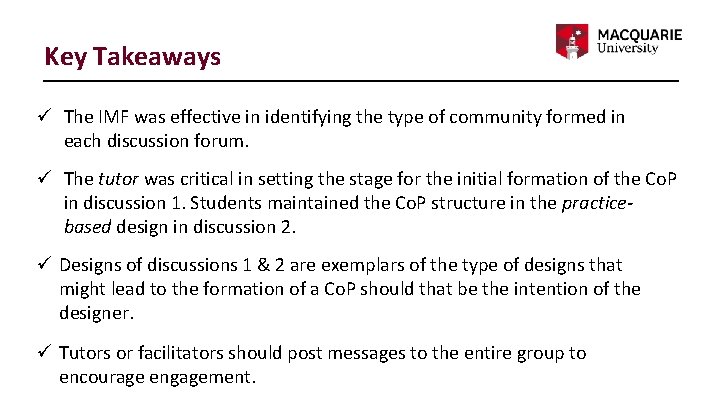

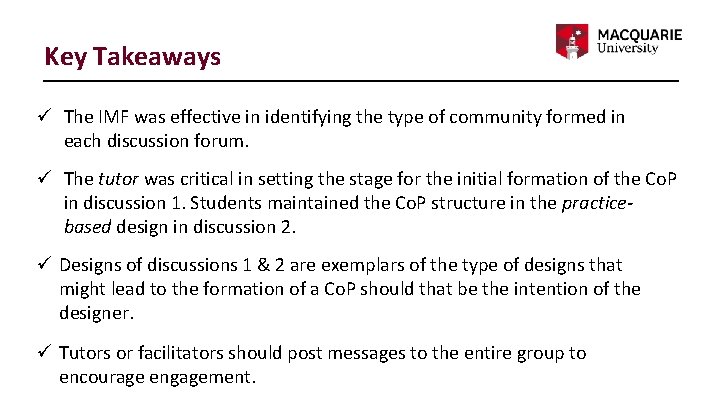

Key Takeaways ü The IMF was effective in identifying the type of community formed in each discussion forum. ü The tutor was critical in setting the stage for the initial formation of the Co. P in discussion 1. Students maintained the Co. P structure in the practicebased design in discussion 2. ü Designs of discussions 1 & 2 are exemplars of the type of designs that might lead to the formation of a Co. P should that be the intention of the designer. ü Tutors or facilitators should post messages to the entire group to encourage engagement.

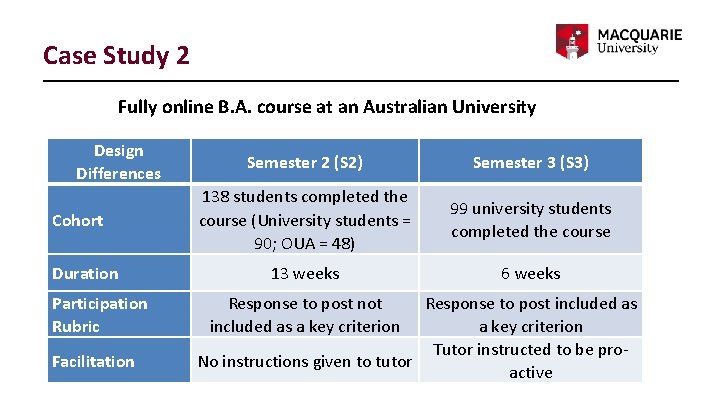

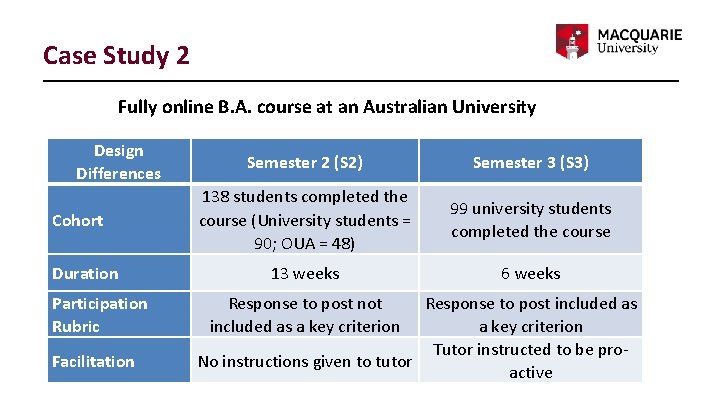

Case Study 2 Fully online B. A. course at an Australian University Design Differences Cohort Duration Participation Rubric Facilitation Semester 2 (S 2) Semester 3 (S 3) 138 students completed the course (University students = 90; OUA = 48) 99 university students completed the course 13 weeks 6 weeks Response to post not included as a key criterion Response to post included as a key criterion Tutor instructed to be pro. No instructions given to tutor active

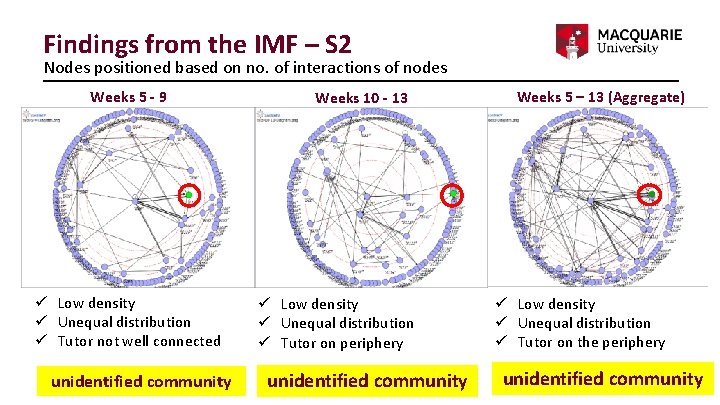

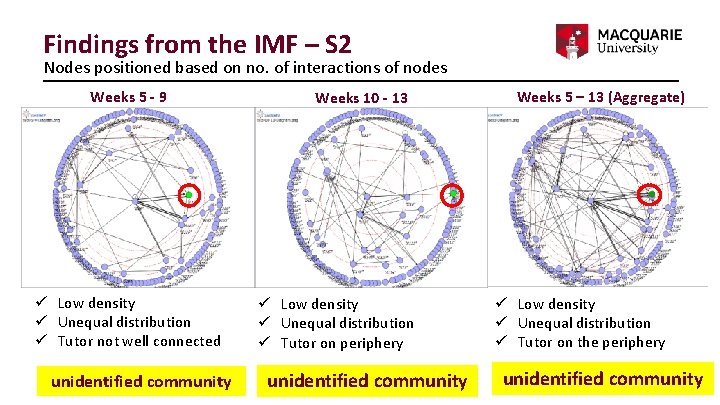

Findings from the IMF – S 2 Nodes positioned based on no. of interactions of nodes Weeks 5 - 9 ü Low density ü Unequal distribution ü Tutor not well connected unidentified community Weeks 10 - 13 ü Low density ü Unequal distribution ü Tutor on periphery unidentified community Weeks 5 – 13 (Aggregate) ü Low density ü Unequal distribution ü Tutor on the periphery unidentified community

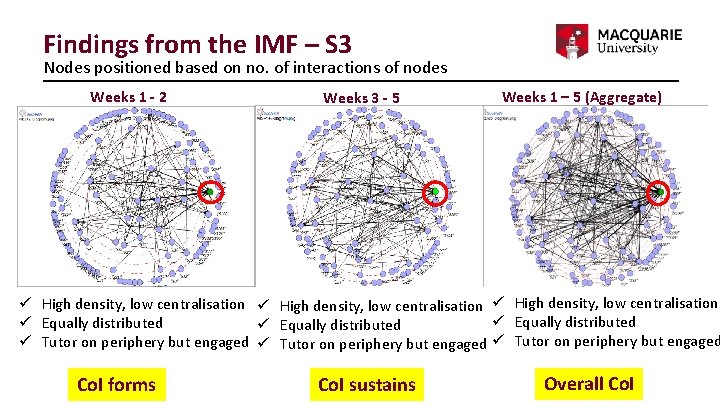

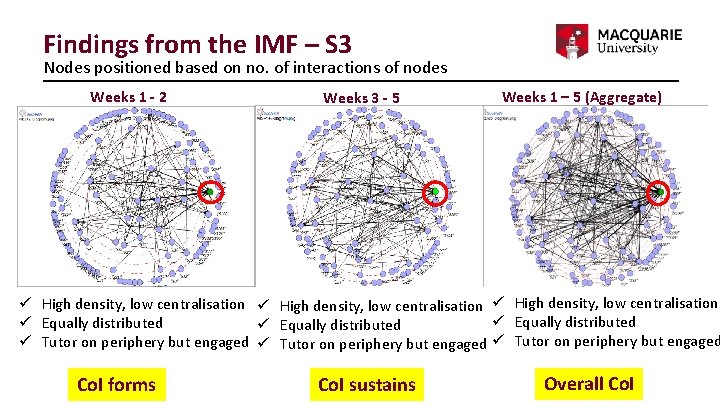

Findings from the IMF – S 3 Nodes positioned based on no. of interactions of nodes Weeks 1 - 2 Weeks 3 - 5 Weeks 1 – 5 (Aggregate) ü High density, low centralisation ü Equally distributed ü Tutor on periphery but engaged Co. I forms Co. I sustains Overall Co. I

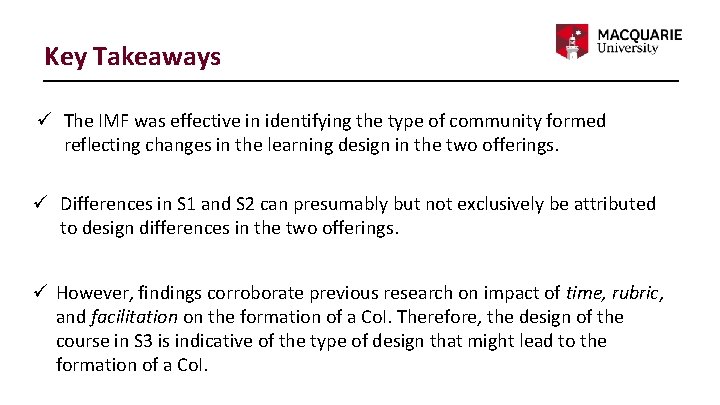

Key Takeaways ü The IMF was effective in identifying the type of community formed reflecting changes in the learning design in the two offerings. ü Differences in S 1 and S 2 can presumably but not exclusively be attributed to design differences in the two offerings. ü However, findings corroborate previous research on impact of time, rubric, and facilitation on the formation of a Co. I. Therefore, the design of the course in S 3 is indicative of the type of design that might lead to the formation of a Co. I.

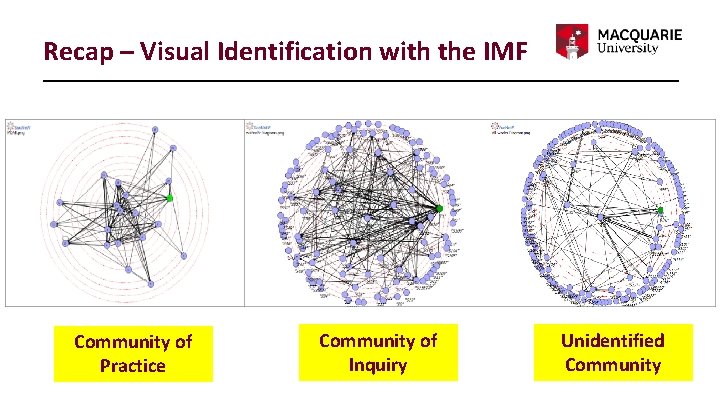

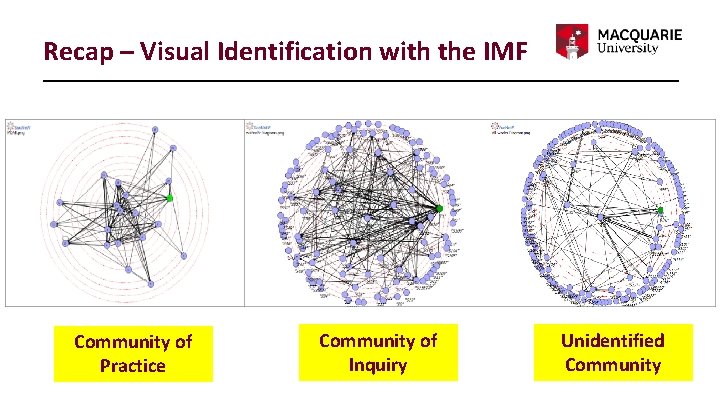

Recap – Visual Identification with the IMF Community of Practice Community of Inquiry Unidentified Community

Implications of Research ü The IMF presents as a unique tool for a preliminary structural evaluation of learner engagement in light of the Co. P and Co. I frameworks – in real time or otherwise. ü The IMF provides a lens for making pedagogical sense of large amounts of online data. ü As it is, the IMF is useful for researchers of online learning communities familiar with SNA. ü In future, automation of data extraction and manipulation and integration with LMSs will extend the utility of the IMF to academics and practitioners.

Limitations ü The IMF does not imply that learning within one particular type of community is better than another, or even that community-based learning is more effective than otherwise. ü Further validation with selective qualitative analysis post preliminary identification of communities is yet to be undertaken. ü Data collection for SNA requires special ethical considerations, e. g. anonymity of non-participants cannot be guaranteed.

Further Research ü Integration of the IMF with attributional data to explore the relationships between engagement, individual attributes (e. g. goal orientation, self-efficacy, etc. ). ü Inclusion of performance data to explore the relationships between performance, placement and roles in Co. Ps and Co. Is. ü Further testing and refinement of the IMF to include more SNA measures and Co. P/Co. I constructs.

Publications 1. Jan, S. K. , Vlachopoulos, P. , & Parsell, M. (2019). Social network analysis and learning communities in higher education online learning: A systematic literature review. Online Learning, 23(1), 249 -264. 2. Jan, S. K. (2018). Investigating virtual communities of practice with social network analysis: guidelines from a systematic review of research. International Journal of Web-based Communities, 15(1), 25 -43. 3. Jan, S. K. , & Vlachopoulos, P. (2018). Social network analysis: A framework for identifying communities in higher education online learning. Technology, Knowledge and Learning. https: //doi. org/10. 1007/s 10758 -018 -9375 -y 4. Jan, S. K. , & Vlachopoulos, P. (2018). Influence of learning design on the formation of online communities of learning. International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, (19)4. https: //doi. org/10. 19173/irrodl. v 19 i 4. 3620 5. Jan, S. (2018). Identifying online communities of inquiry in higher education using social network analysis. Research in Learning Technology, 26. https: //doi. org/10. 25304/rlt. v 26. 2064

Special thanks… Associate Professor Panos Vlachopoulos Associate Dean, Curriculum & Quality Faculty of Arts, Macquarie University Associate Professor Mitch Parsell Associate Dean, Learning & Teaching Faculty of Human Sciences, Macquarie University

Thank you