http music princeton edudmitr A Geometry of Music

- Slides: 44

http: //music. princeton. edu/~dmitr A Geometry of Music Dmitri Tymoczko Princeton University dmitri@princeton. edu http: //music. princeton. edu/~dmitri/SIAM. ppt

http: //music. princeton. edu/~dmitr What makes music sound good? • Melodies move by short distances (horizontal) – Auditory streaming • Harmonies sound similar (vertical) – chords, whatever they are, are structurally similar • Chords sound intrinsically good (“acoustic consonance”) • “Limited macroharmony” – Music is limited to 5 -8 pitch-classes over moderate stretches of time. • Centricity (one note sounds “stable” or restful) • Universality vs. cultural conditioning; possible contributions of biology

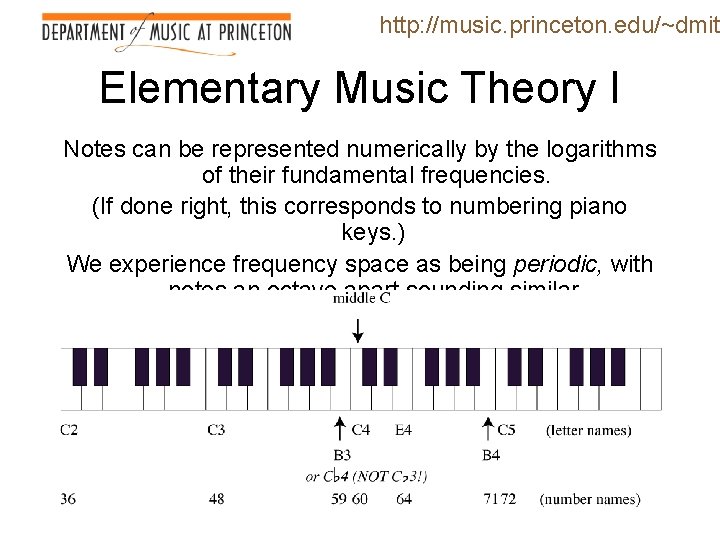

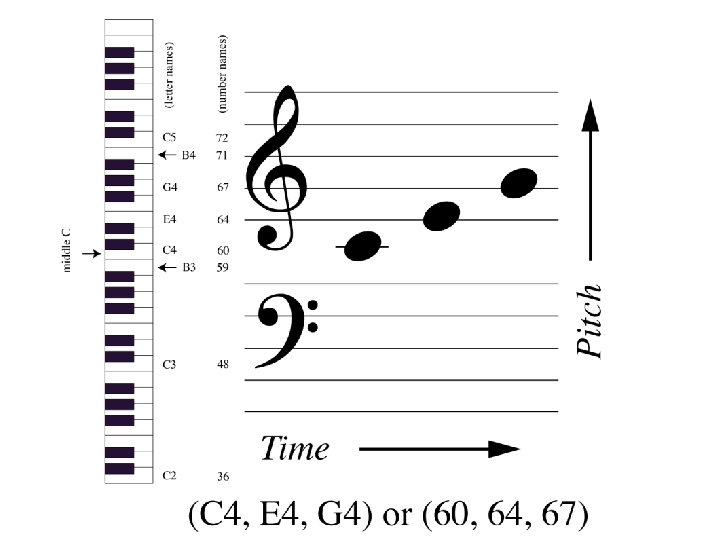

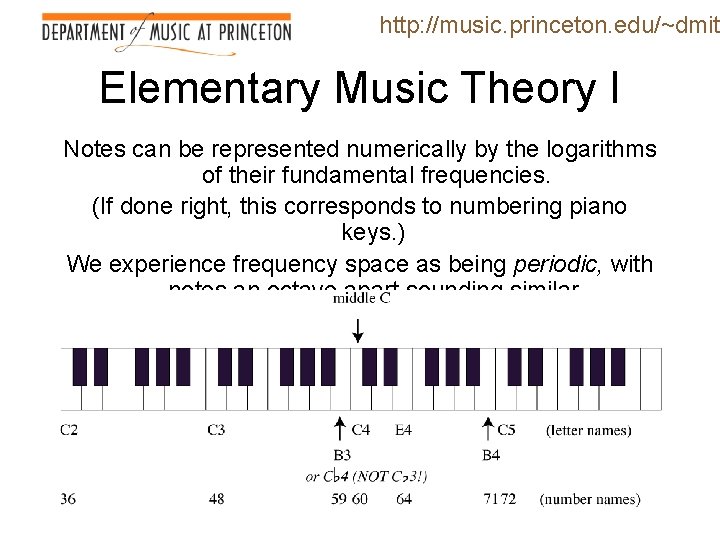

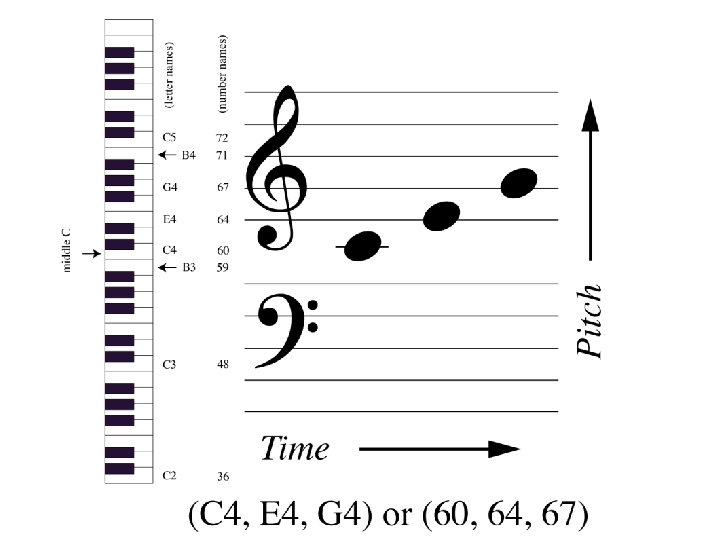

http: //music. princeton. edu/~dmitr Elementary Music Theory I Notes can be represented numerically by the logarithms of their fundamental frequencies. (If done right, this corresponds to numbering piano keys. ) We experience frequency space as being periodic, with notes an octave apart sounding similar

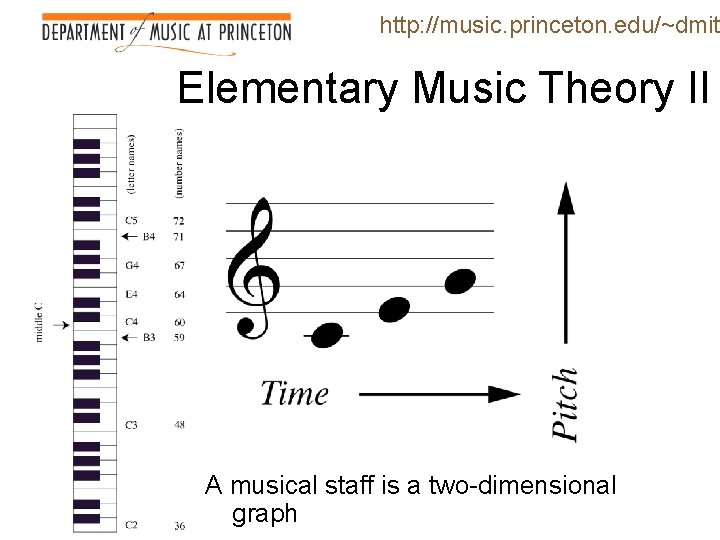

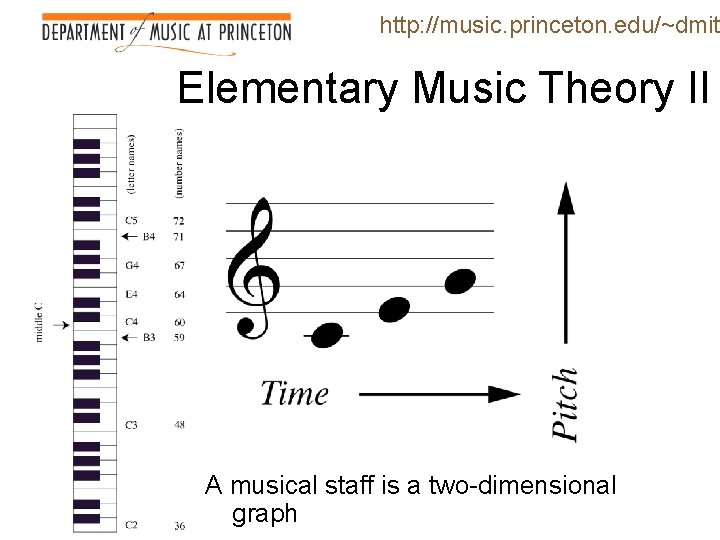

http: //music. princeton. edu/~dmitr Elementary Music Theory II A musical staff is a two-dimensional graph

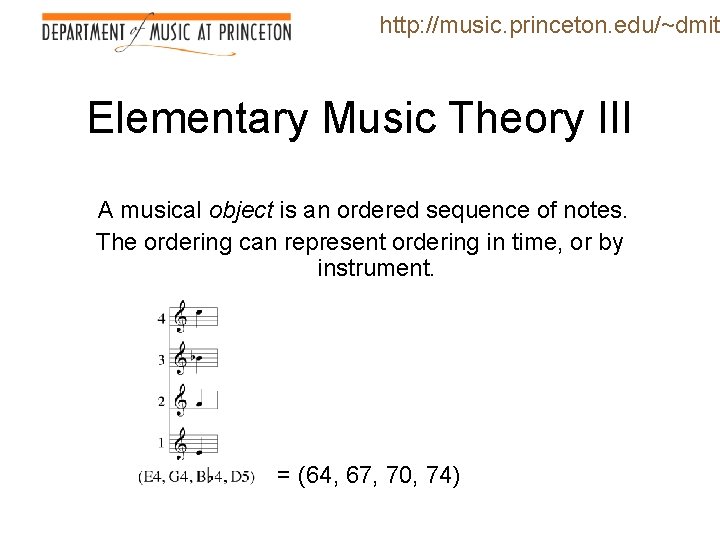

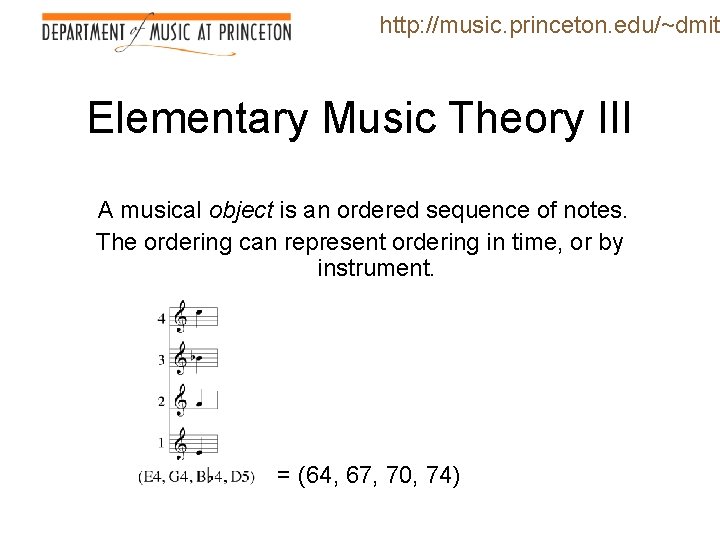

http: //music. princeton. edu/~dmitr Elementary Music Theory III A musical object is an ordered sequence of notes. The ordering can represent ordering in time, or by instrument. = (64, 67, 70, 74)

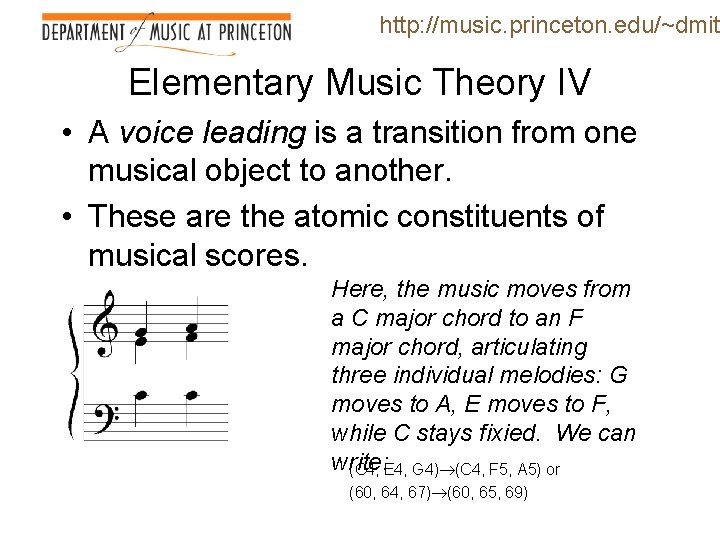

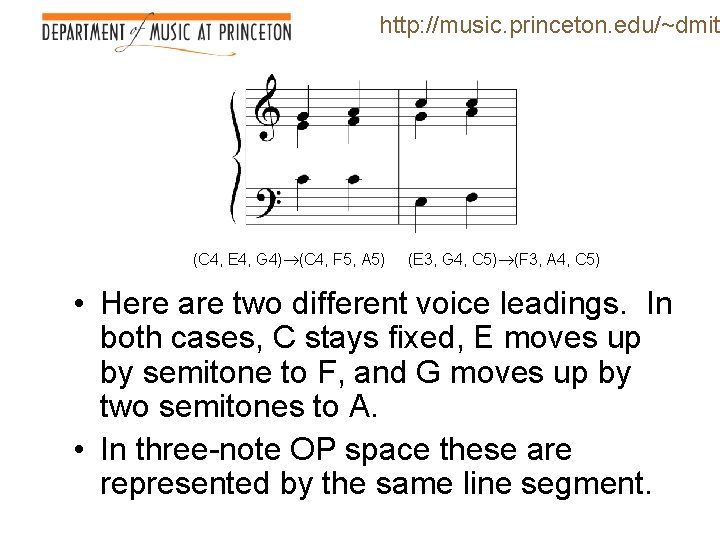

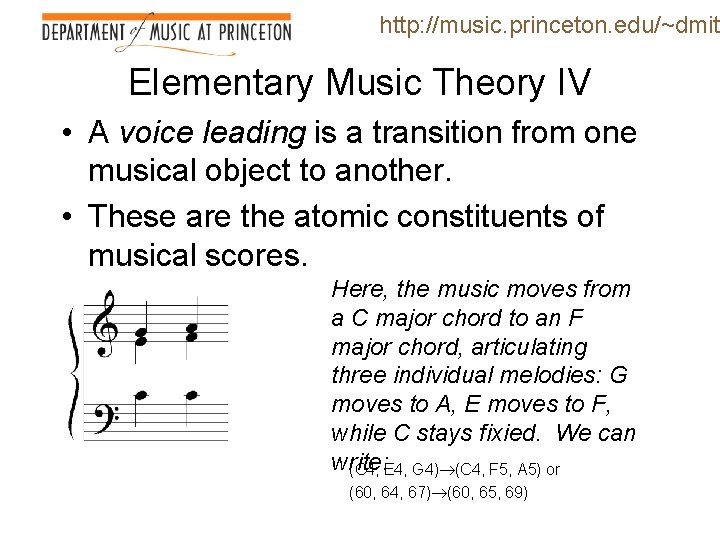

http: //music. princeton. edu/~dmitr Elementary Music Theory IV • A voice leading is a transition from one musical object to another. • These are the atomic constituents of musical scores. Here, the music moves from a C major chord to an F major chord, articulating three individual melodies: G moves to A, E moves to F, while C stays fixied. We can write: (C 4, E 4, G 4) (C 4, F 5, A 5) or (60, 64, 67) (60, 65, 69)

http: //music. princeton. edu/~dmitr Symmetry and Music • Musicians are in the business of combining similar objects. • What does it mean to say two objects are similar (or “functionally equivalent”)? • Or in other words, what sorts of symmetries do musicians habitually recognize?

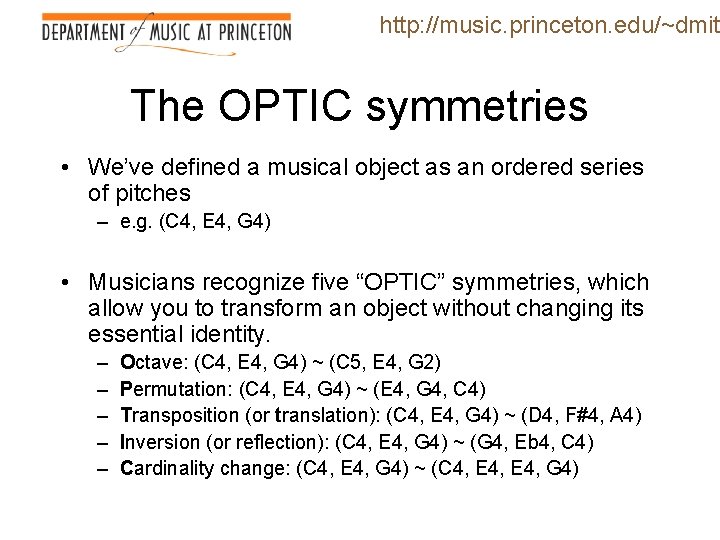

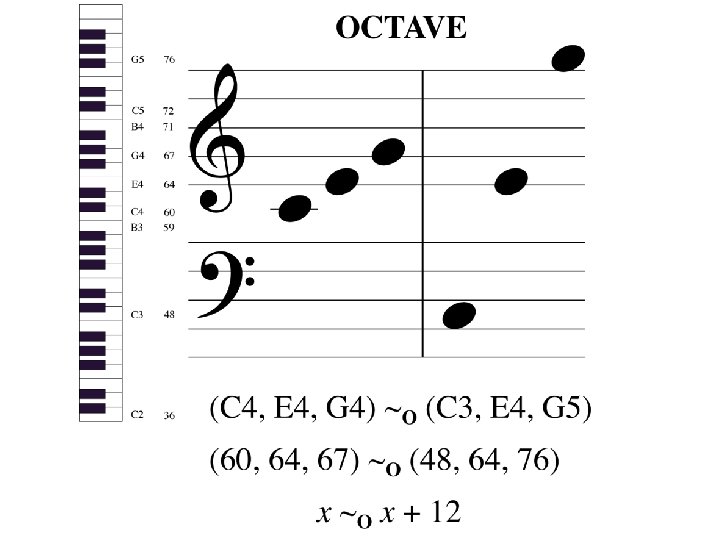

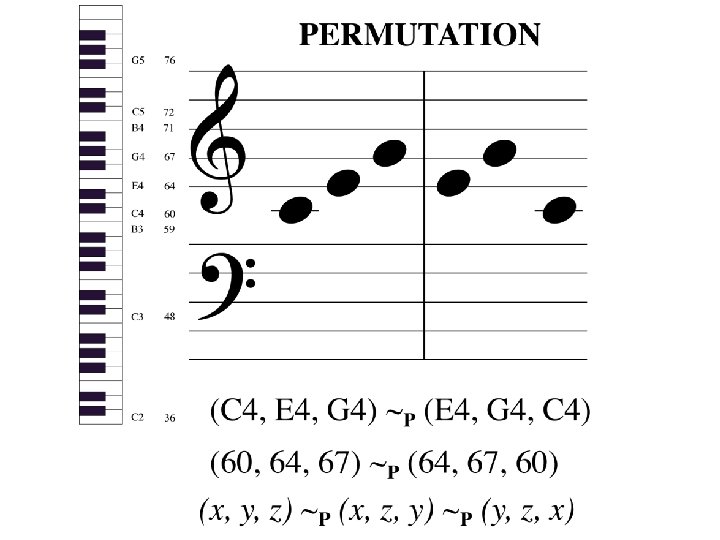

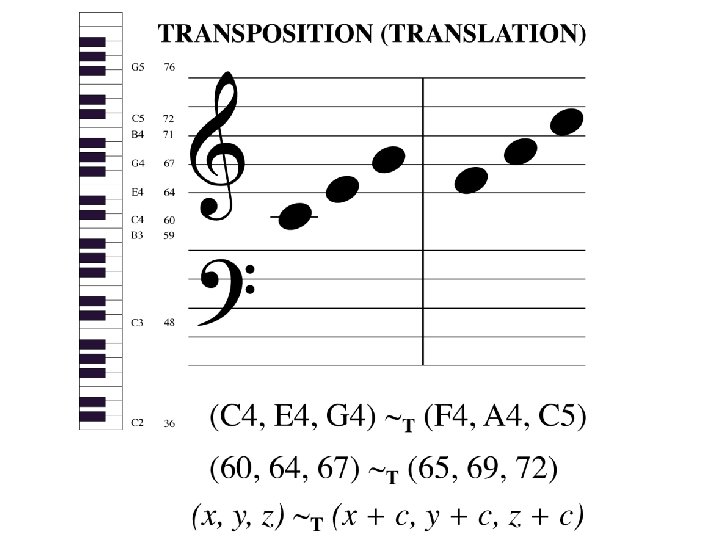

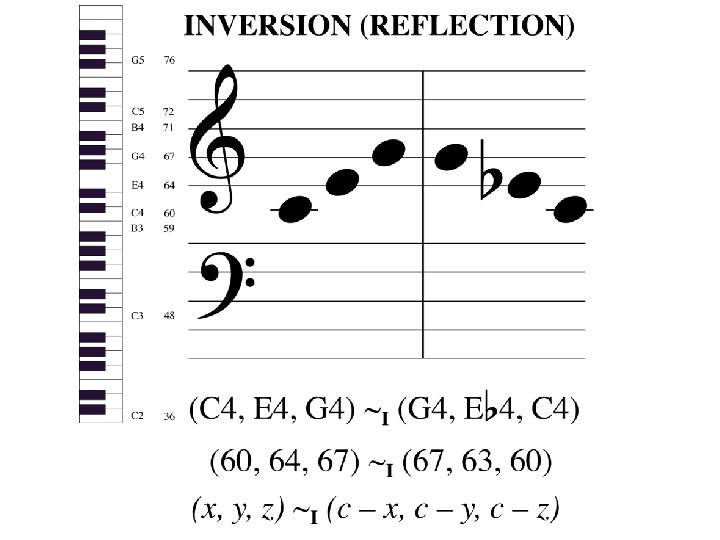

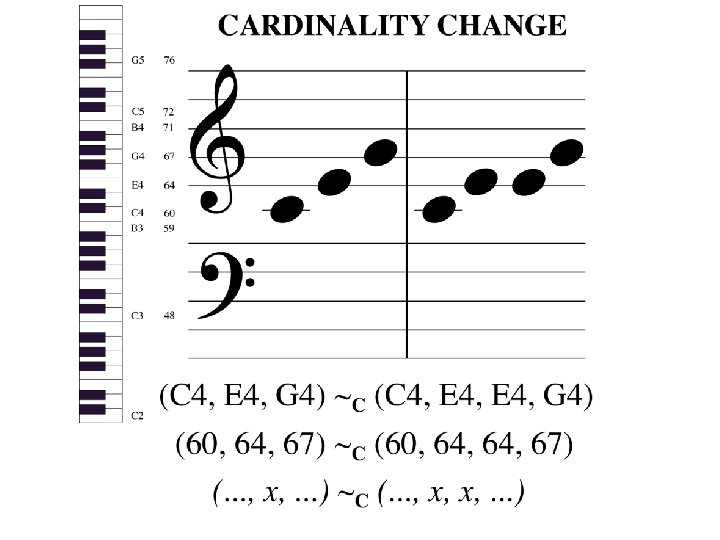

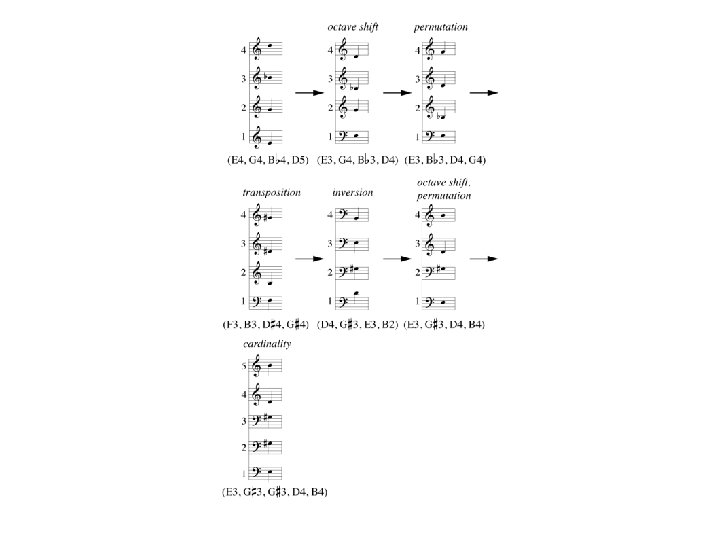

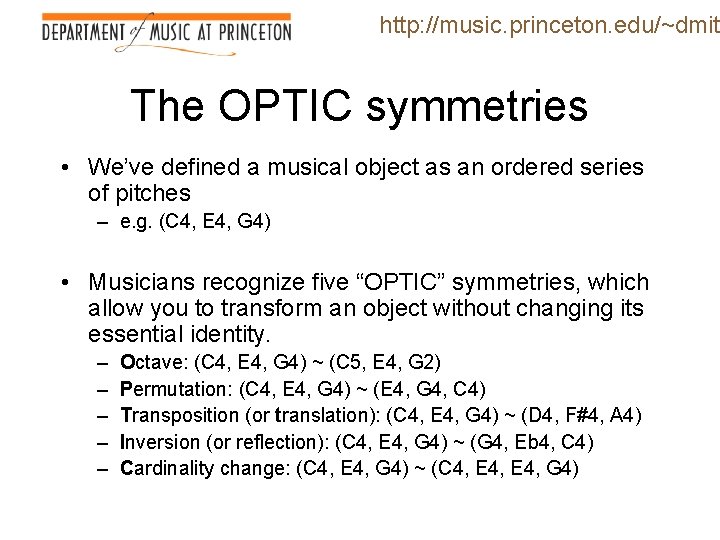

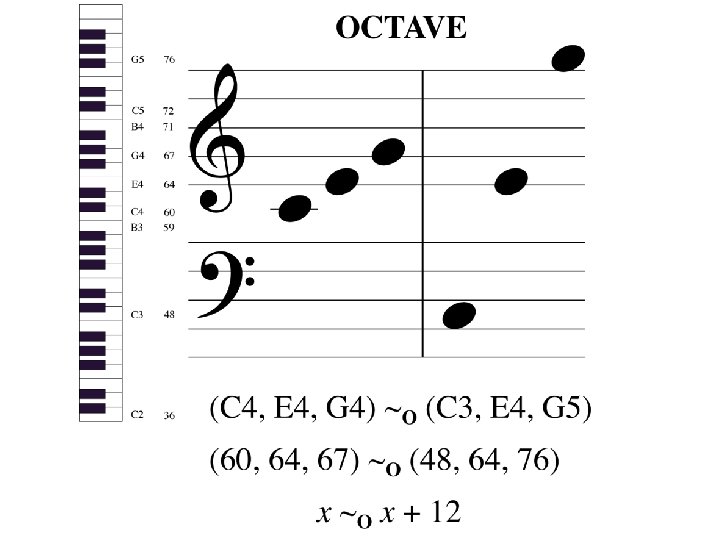

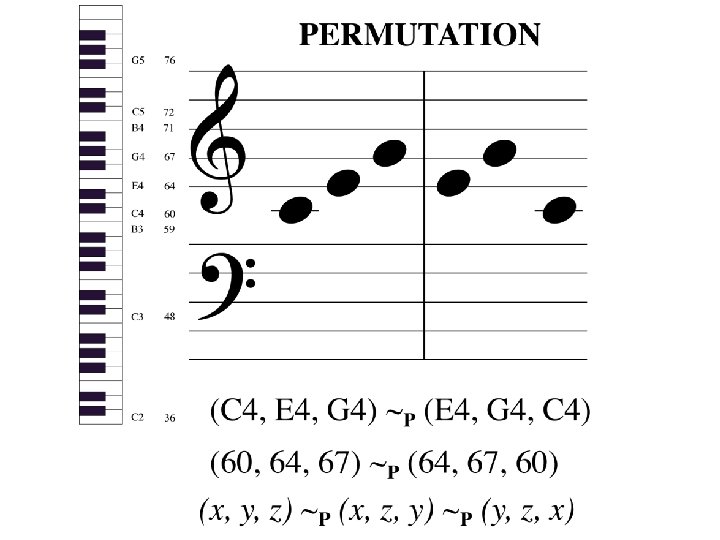

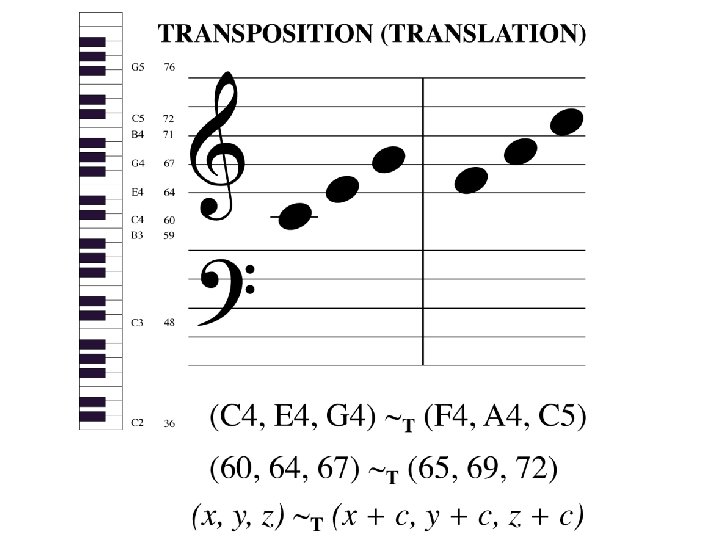

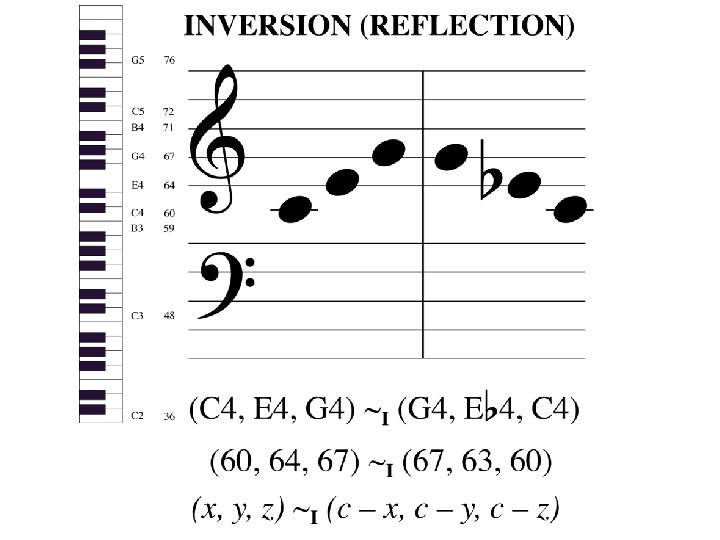

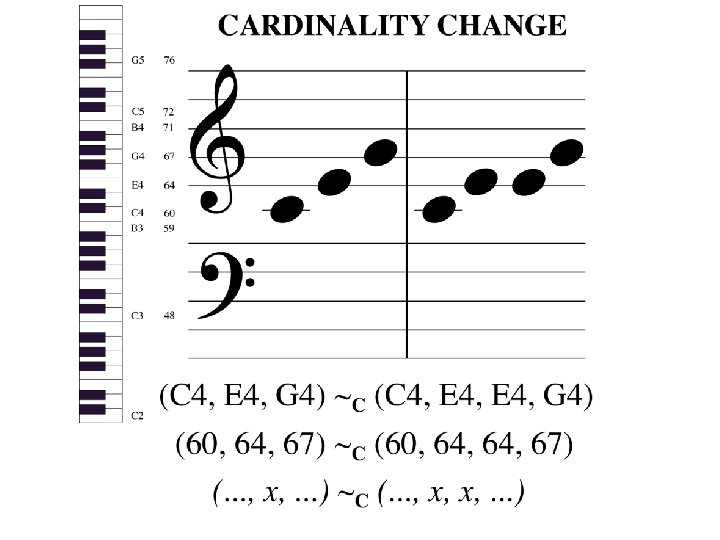

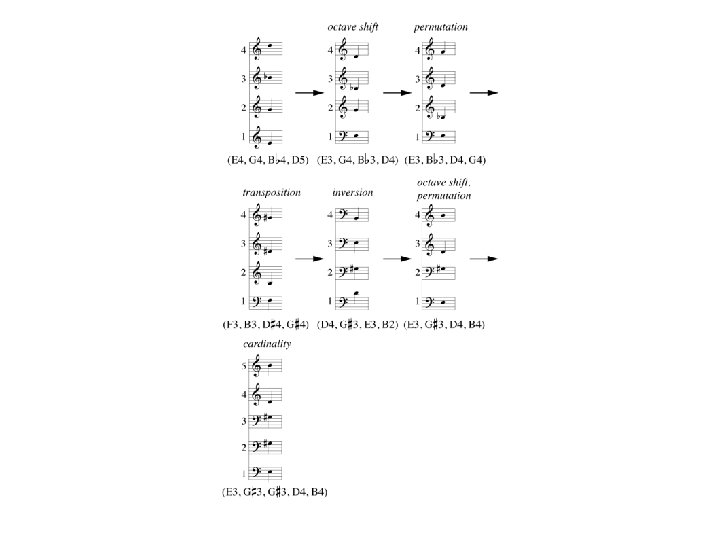

http: //music. princeton. edu/~dmitr The OPTIC symmetries • We’ve defined a musical object as an ordered series of pitches – e. g. (C 4, E 4, G 4) • Musicians recognize five “OPTIC” symmetries, which allow you to transform an object without changing its essential identity. – – – Octave: (C 4, E 4, G 4) ~ (C 5, E 4, G 2) Permutation: (C 4, E 4, G 4) ~ (E 4, G 4, C 4) Transposition (or translation): (C 4, E 4, G 4) ~ (D 4, F#4, A 4) Inversion (or reflection): (C 4, E 4, G 4) ~ (G 4, Eb 4, C 4) Cardinality change: (C 4, E 4, G 4) ~ (C 4, E 4, G 4)

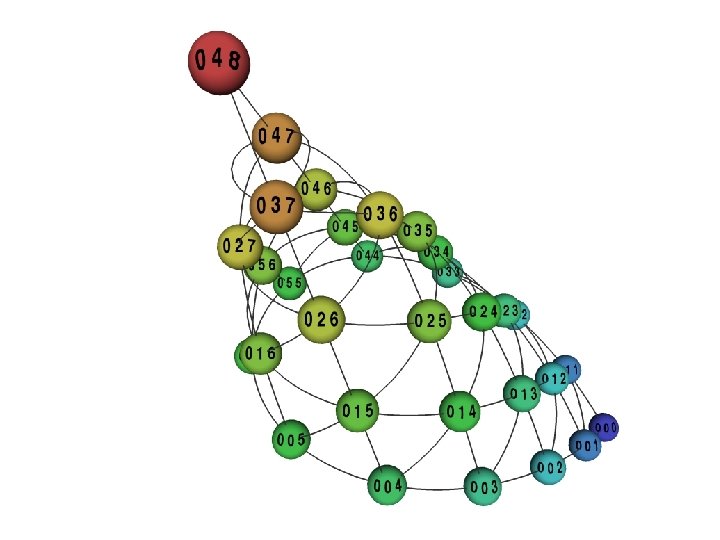

http: //music. princeton. edu/~dmitr Common Musical Terms expressed in terms of the OPTIC symmetries • Chord (e. g. “C major”) = OPC equivalence class • Chord type (e. g. “major chord”) = OPTC equivalence class • Many others: pitch, pitch-class, chord progression, voice leading, tone row, set class, etc.

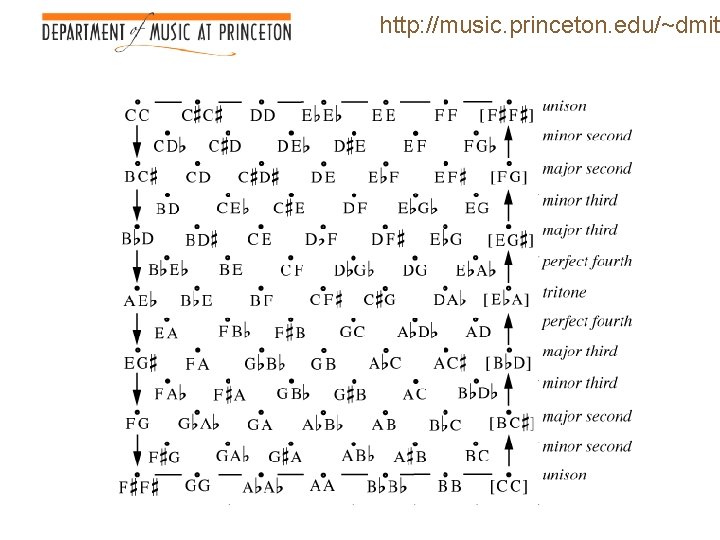

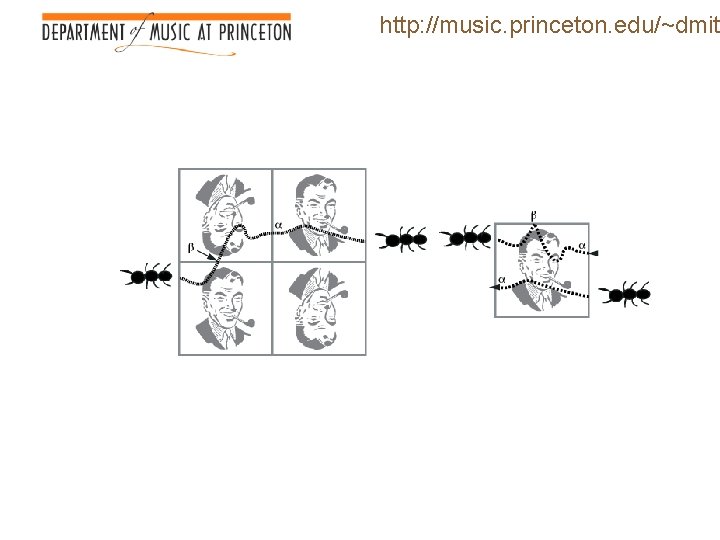

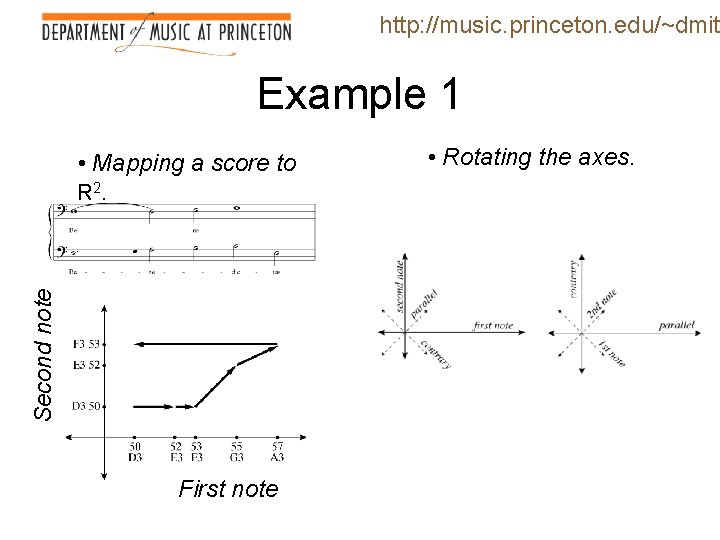

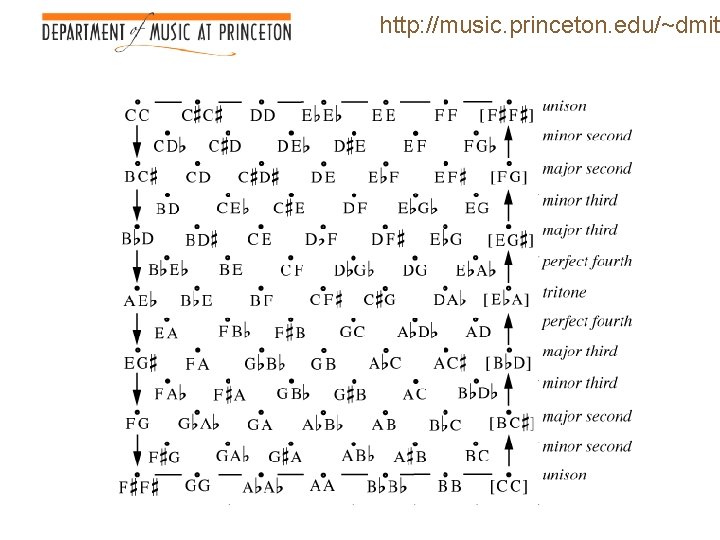

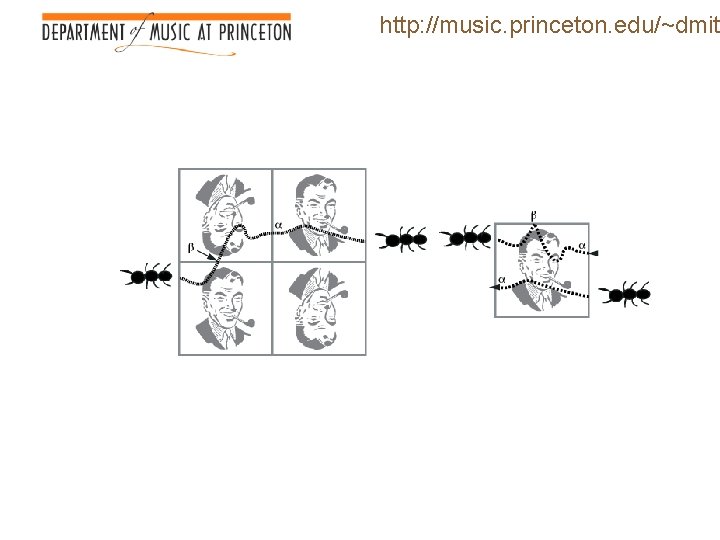

http: //music. princeton. edu/~dmitr Geometry • Each combination of OPTIC symmetries produces its own geometrical space. • These spaces are quotients of Rn. • Example 1: two-note chords. – Start with the Cartesian plane, R 2. – Identify all points (x, y), (y, x), (x+12, y) • NB: (x, y) ~ (y, x) ~ (y+12, x) ~ (x, y + 12) – The result is an orbifold: a Möbius strip whose singular “boundary” acts like a mirror.

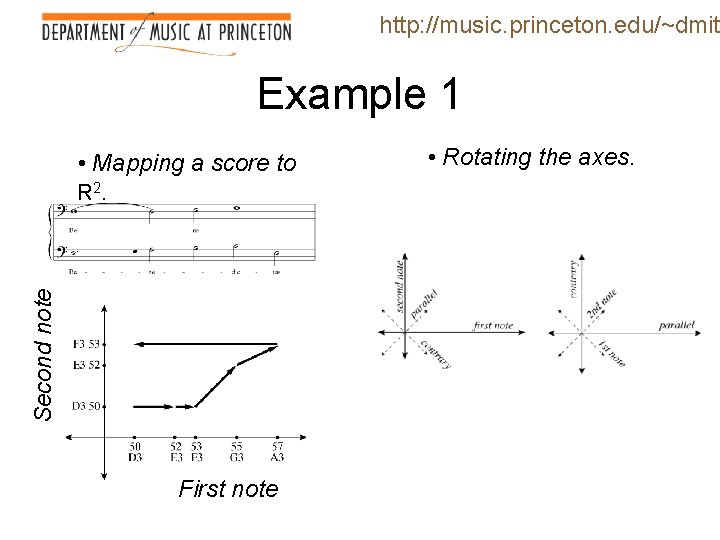

http: //music. princeton. edu/~dmitr Example 1 Second note • Mapping a score to R 2. First note • Rotating the axes.

http: //music. princeton. edu/~dmitr

http: //music. princeton. edu/~dmitr

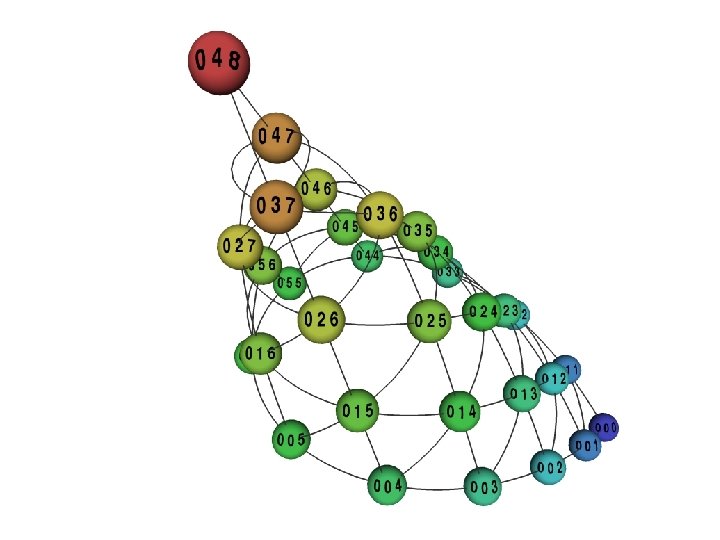

http: //music. princeton. edu/~dmitr Geometry (2) • Example 2: three-note chord types (OPT) – Start with the Cartesian plane, R 3. – Identify (x, y, z) with: • (x+12, y, z) • (y, x, z), (y, z, x) • (x + c, y + c, z + c) – The result is a cone whose “boundary” acts as a mirror, and whose tip is singular. – Mathematically, this is the leaf space of a foliation of the bounded interior of a twisted triangular 2 -torus.

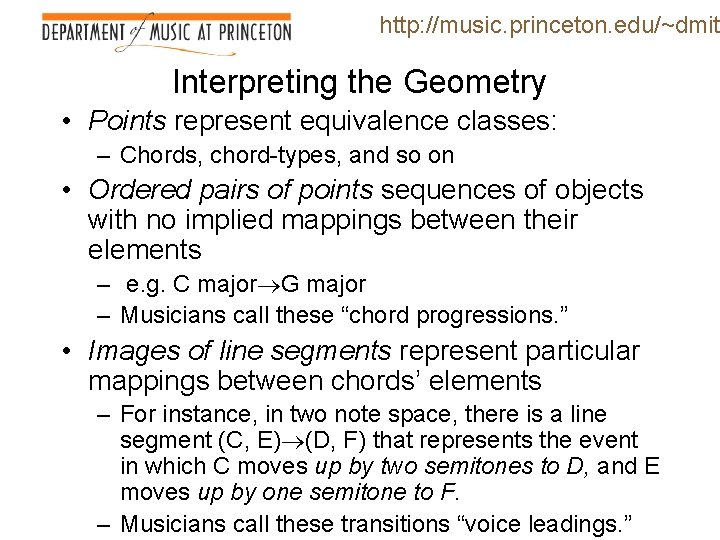

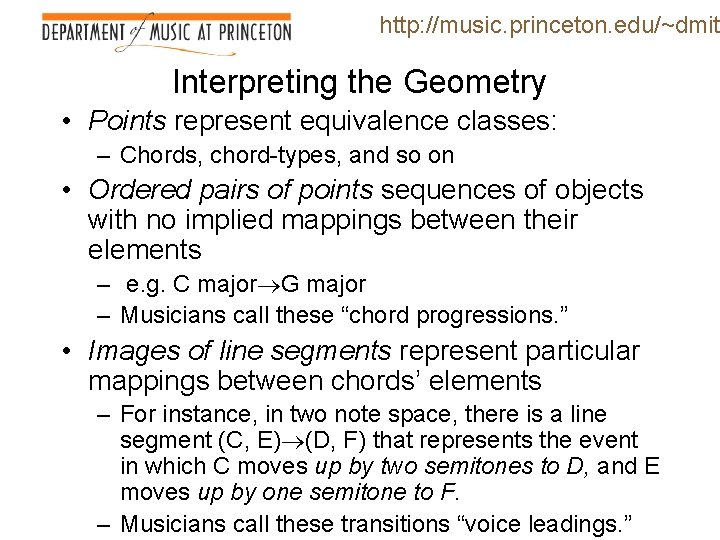

http: //music. princeton. edu/~dmitr Interpreting the Geometry • Points represent equivalence classes: – Chords, chord-types, and so on • Ordered pairs of points sequences of objects with no implied mappings between their elements – e. g. C major G major – Musicians call these “chord progressions. ” • Images of line segments represent particular mappings between chords’ elements – For instance, in two note space, there is a line segment (C, E) (D, F) that represents the event in which C moves up by two semitones to D, and E moves up by one semitone to F. – Musicians call these transitions “voice leadings. ”

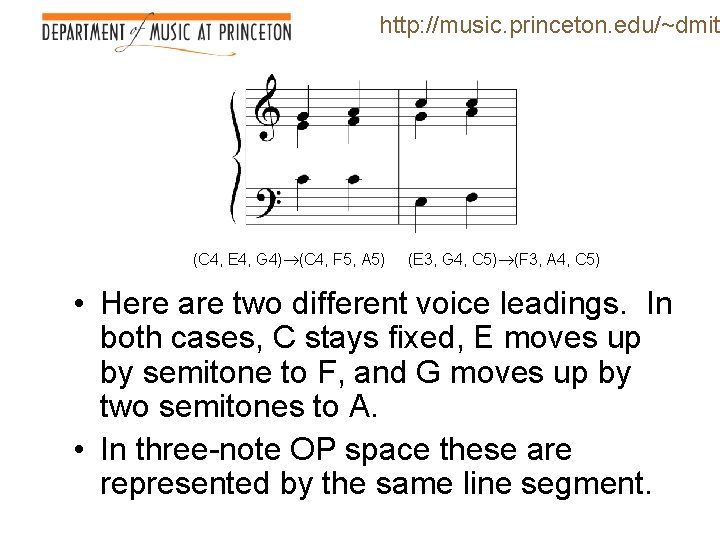

http: //music. princeton. edu/~dmitr (C 4, E 4, G 4) (C 4, F 5, A 5) (E 3, G 4, C 5) (F 3, A 4, C 5) • Here are two different voice leadings. In both cases, C stays fixed, E moves up by semitone to F, and G moves up by two semitones to A. • In three-note OP space these are represented by the same line segment.

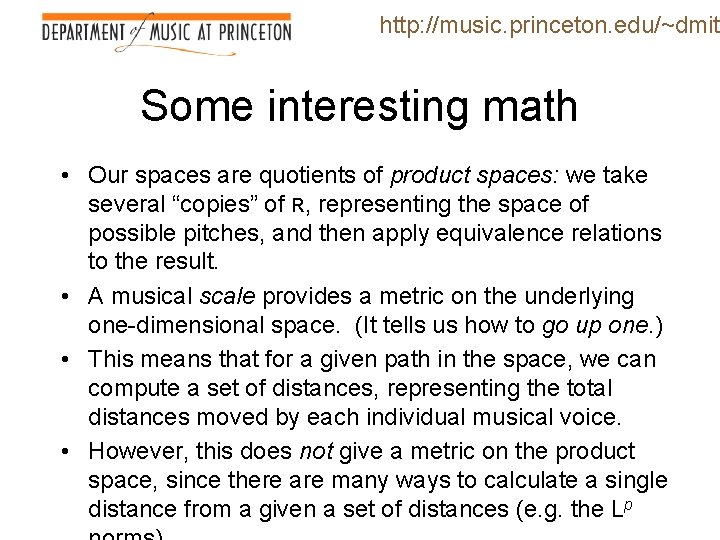

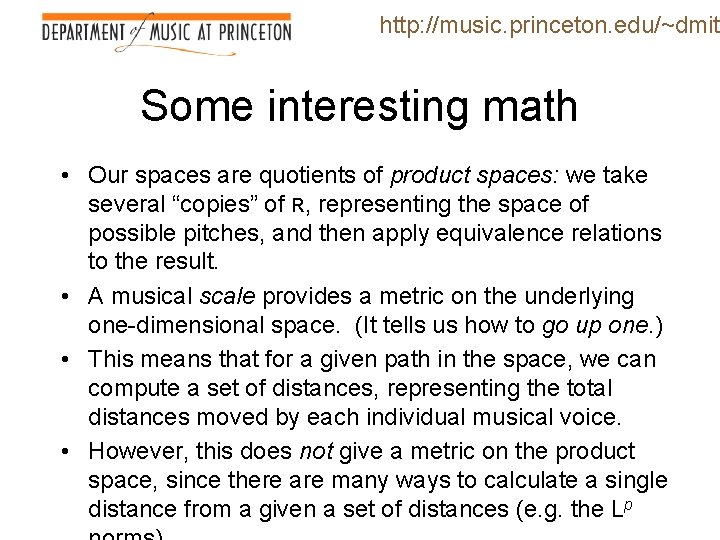

http: //music. princeton. edu/~dmitr Some interesting math • Our spaces are quotients of product spaces: we take several “copies” of R, representing the space of possible pitches, and then apply equivalence relations to the result. • A musical scale provides a metric on the underlying one-dimensional space. (It tells us how to go up one. ) • This means that for a given path in the space, we can compute a set of distances, representing the total distances moved by each individual musical voice. • However, this does not give a metric on the product space, since there are many ways to calculate a single distance from a given a set of distances (e. g. the Lp

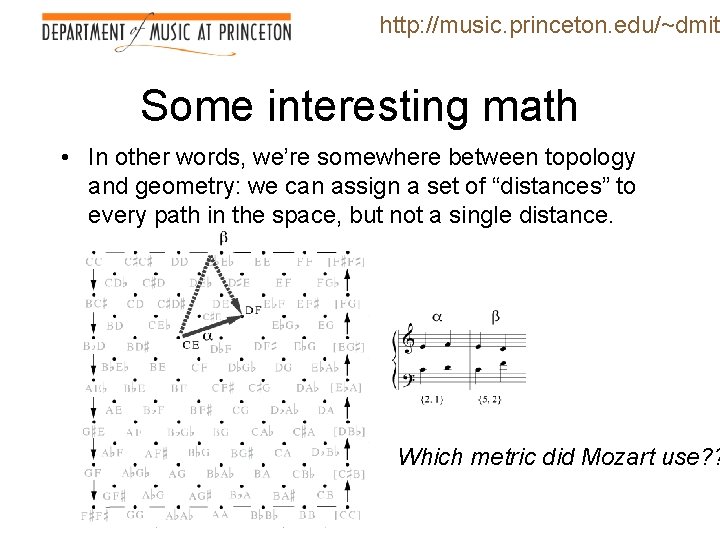

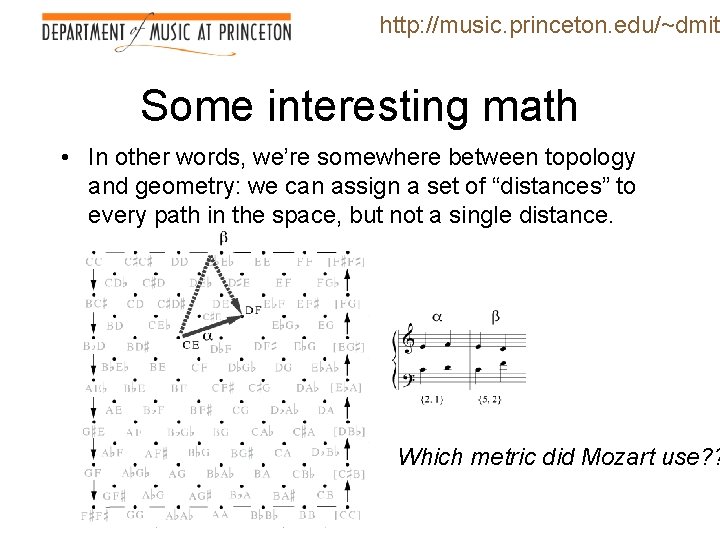

http: //music. princeton. edu/~dmitr Some interesting math • In other words, we’re somewhere between topology and geometry: we can assign a set of “distances” to every path in the space, but not a single distance. Which metric did Mozart use? ?

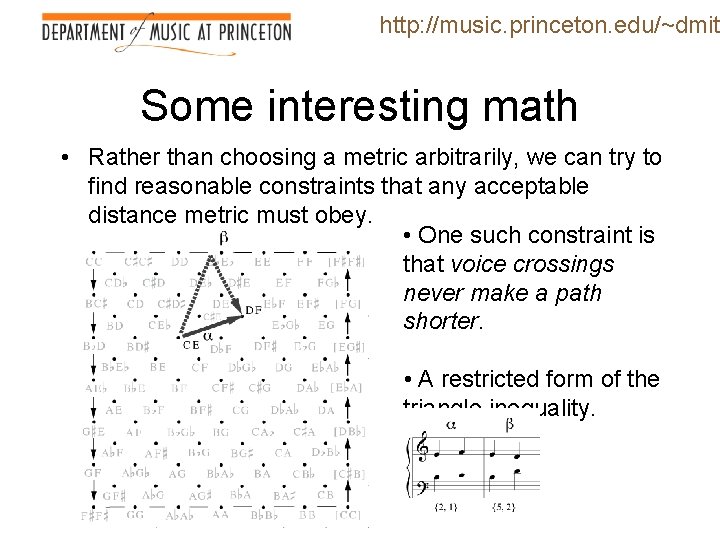

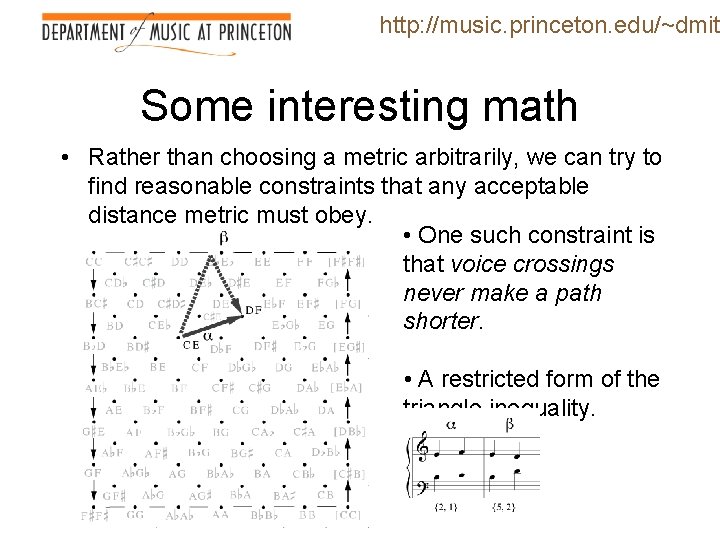

http: //music. princeton. edu/~dmitr Some interesting math • Rather than choosing a metric arbitrarily, we can try to find reasonable constraints that any acceptable distance metric must obey. • One such constraint is that voice crossings never make a path shorter. • A restricted form of the triangle inequality.

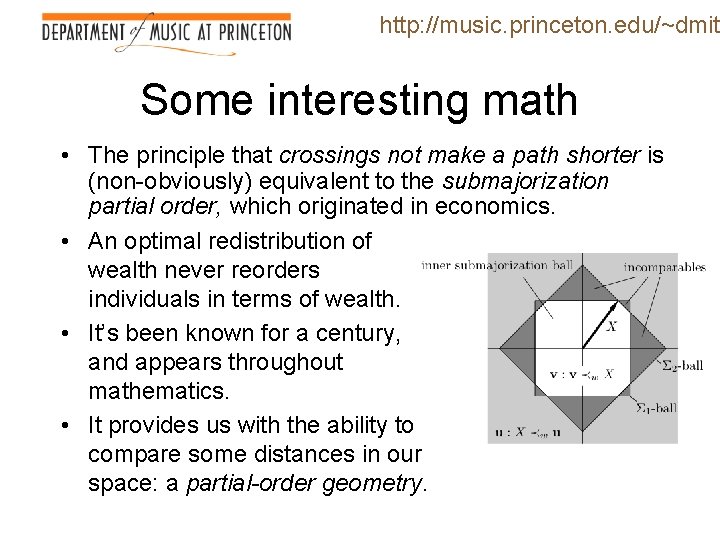

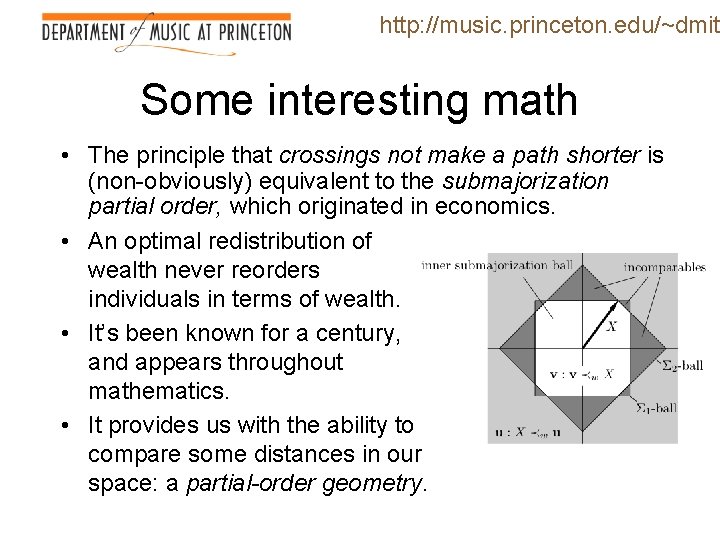

http: //music. princeton. edu/~dmitr Some interesting math • The principle that crossings not make a path shorter is (non-obviously) equivalent to the submajorization partial order, which originated in economics. • An optimal redistribution of wealth never reorders individuals in terms of wealth. • It’s been known for a century, and appears throughout mathematics. • It provides us with the ability to compare some distances in our space: a partial-order geometry.

http: //music. princeton. edu/~dmitr An open problem • Define a chord type as an equivalence class under OPTC: a set of points on the circle modulo transposition (major chord, minor chord, diatonic scale, etc. ). • Define the distance between chord types as the shortest path between them in OPTC space; these paths can involve duplications. – E. g. the shortest path between (0, 4, 6) and (6, 10, 0) is (0, 0, 4, 6) (10, 0, 6, 6) • Q: Given the Euclidean metric, can you construct a polynomialtime algorithm for determining the distance between two chordtypes? – It’s easy for L 1 and L∞, but hard for L 2. – This is a very practical problem, from a musical point of view; it amounts to quantifying a natural notion of similarity.

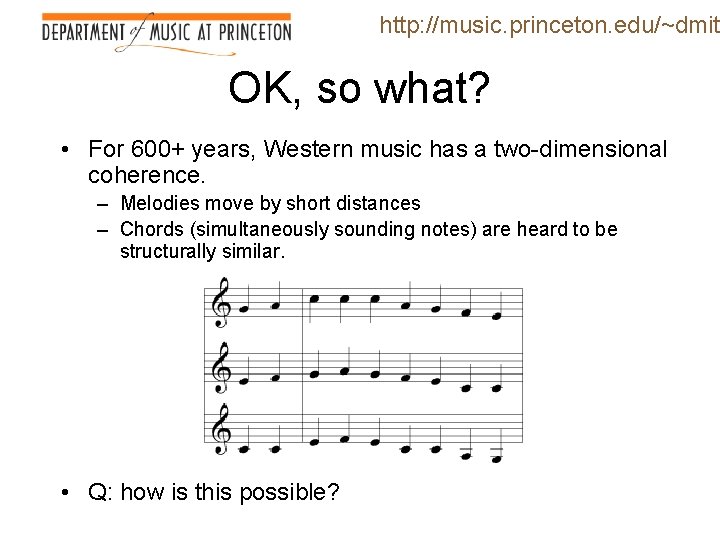

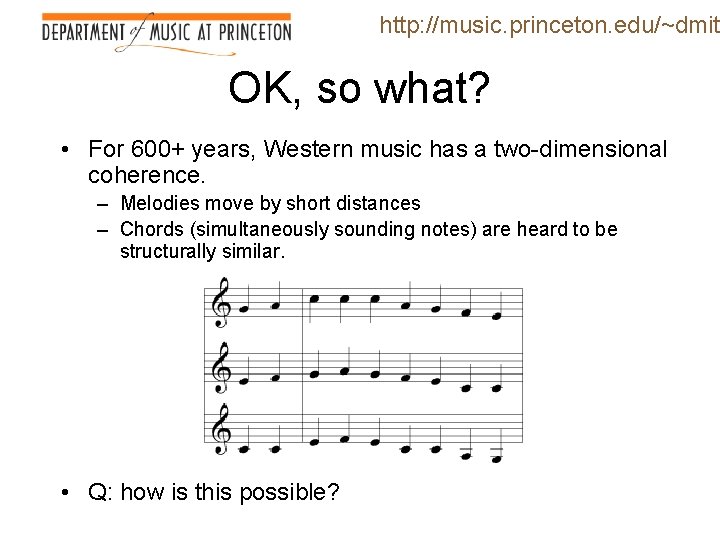

http: //music. princeton. edu/~dmitr OK, so what? • For 600+ years, Western music has a two-dimensional coherence. – Melodies move by short distances – Chords (simultaneously sounding notes) are heard to be structurally similar. • Q: how is this possible?

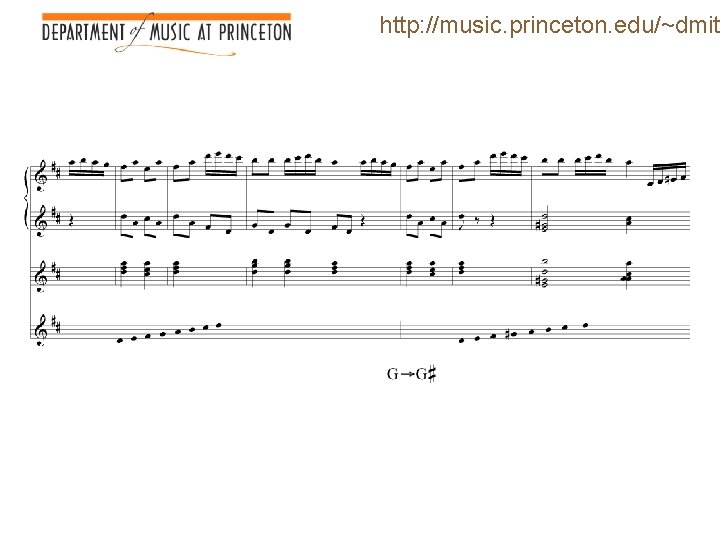

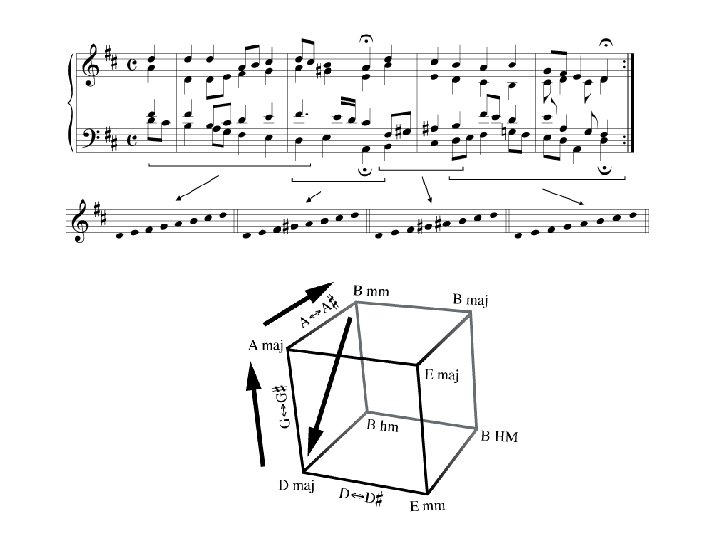

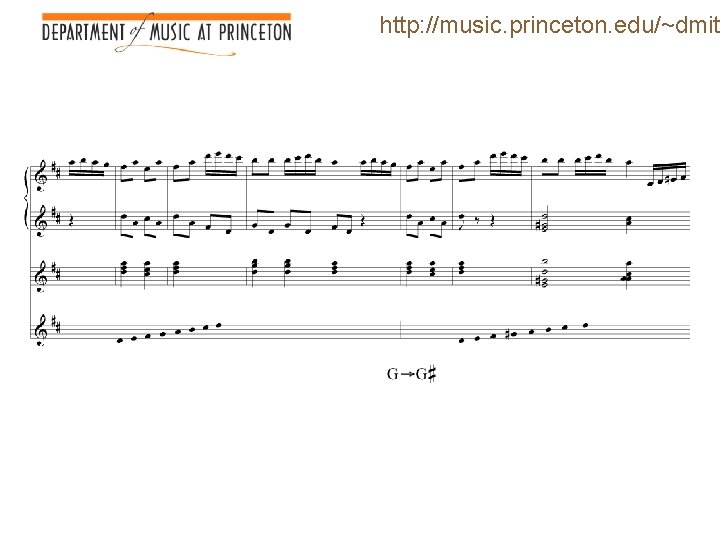

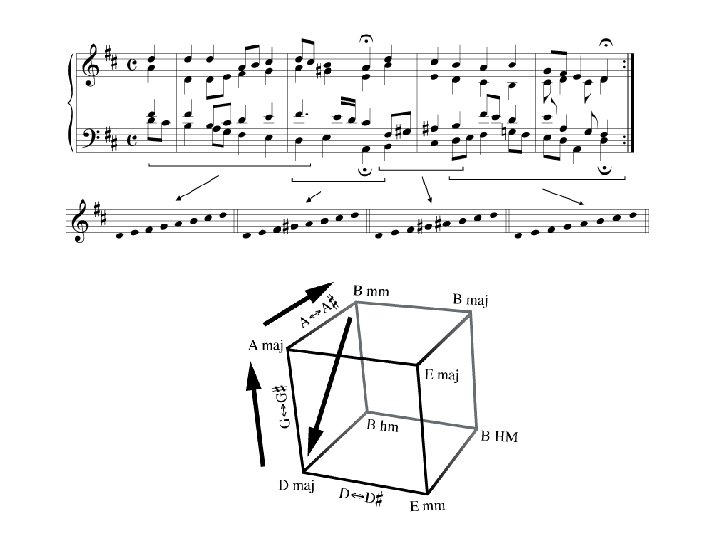

http: //music. princeton. edu/~dmitr Chords and Scales • Furthermore, for 300+ years, Western music has been hierarchically self-similar, combining these two kinds of coherence in two different ways. • When a classical composer moves from the key of D major to the key of A major, the note G moves up by semitone to G#, linking two structurally similar scales (D and A major) by a short melodic motion (G G#).

http: //music. princeton. edu/~dmitr

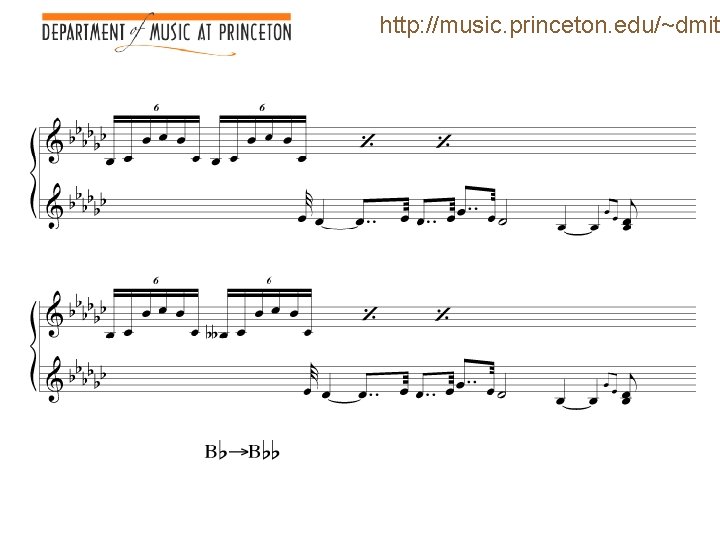

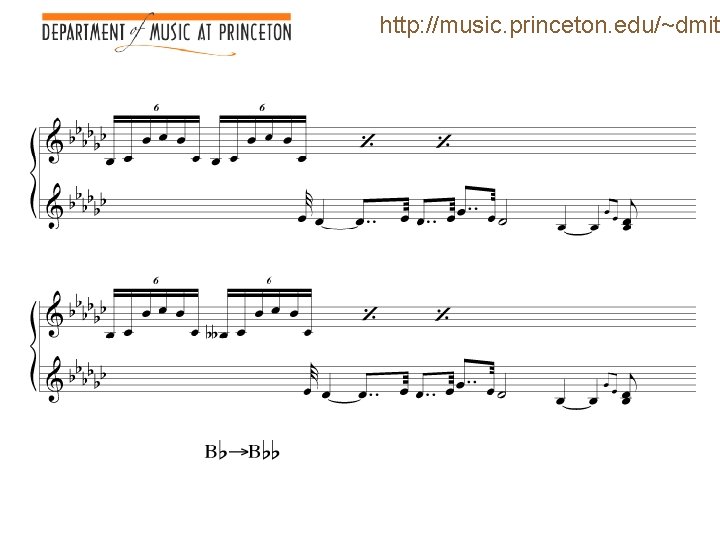

http: //music. princeton. edu/~dmitr

http: //music. princeton. edu/~dmitr Western music is hierarchically self-similar, using the same procedures (short melodic motions linking structurally similar harmonies) at two time scales (that of the chord and that of the scale).

http: //music. princeton. edu/~dmitr If we can understand how this is possible, we can perhaps demarcate the space of coherent musics — that is the range of possible styles exhibiting melodic and harmonic consistency!

http: //music. princeton. edu/~dmitr Geometry to the rescue! • Once you understand the geometry of the OPTIC spaces, it is obvious how to combine melodic and harmonic consistency. • It’s a matter of exploiting the non. Euclidean features of chord space!

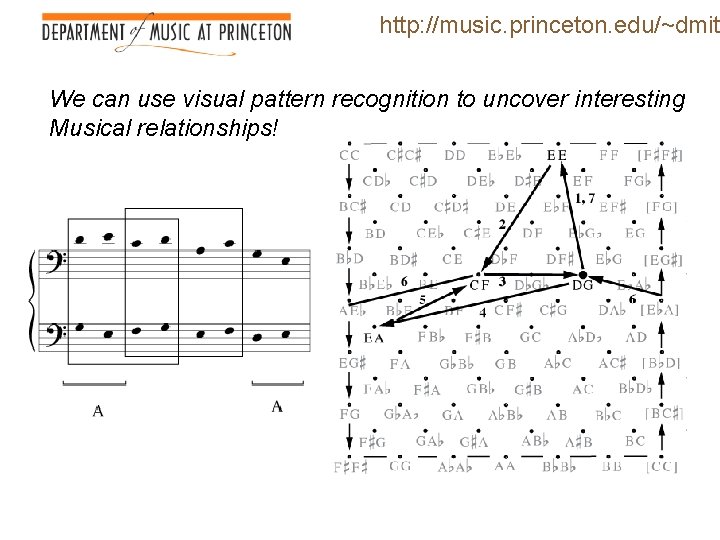

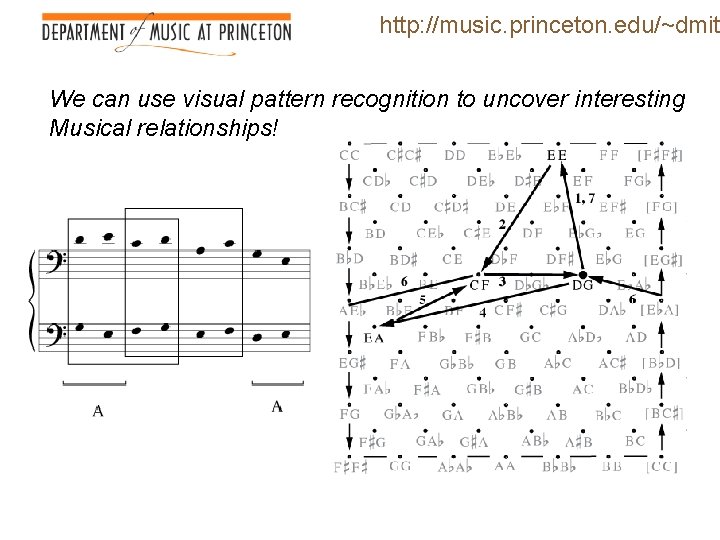

http: //music. princeton. edu/~dmitr We can use visual pattern recognition to uncover interesting Musical relationships!

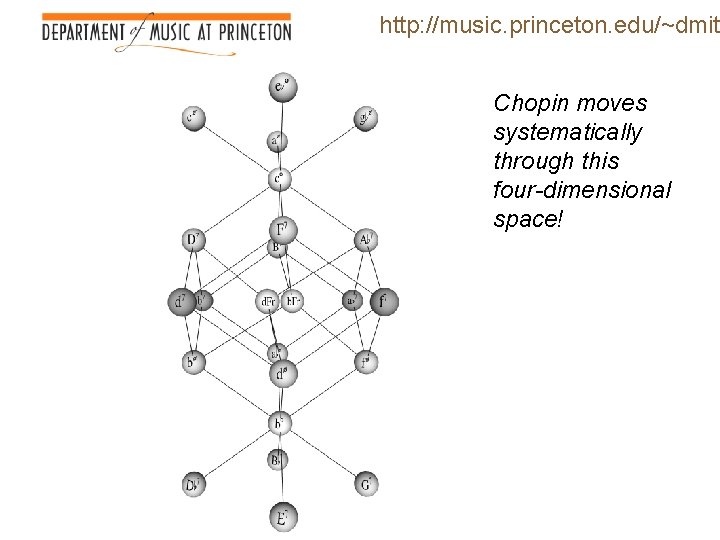

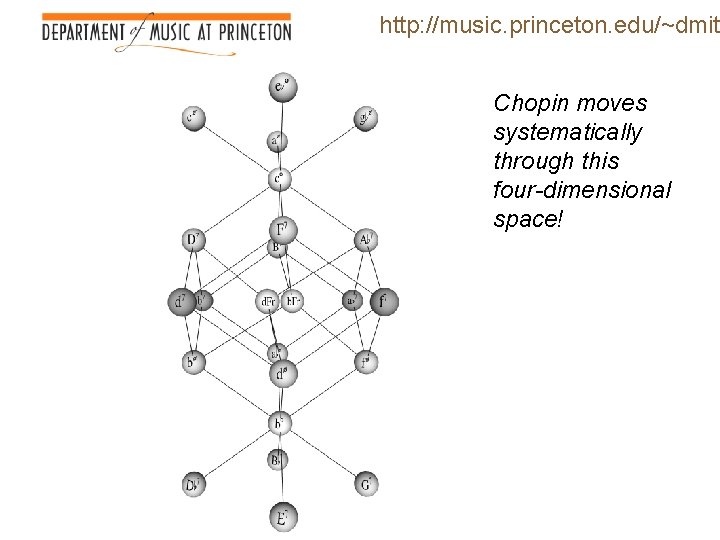

http: //music. princeton. edu/~dmitr Chopin moves systematically through this four-dimensional space!

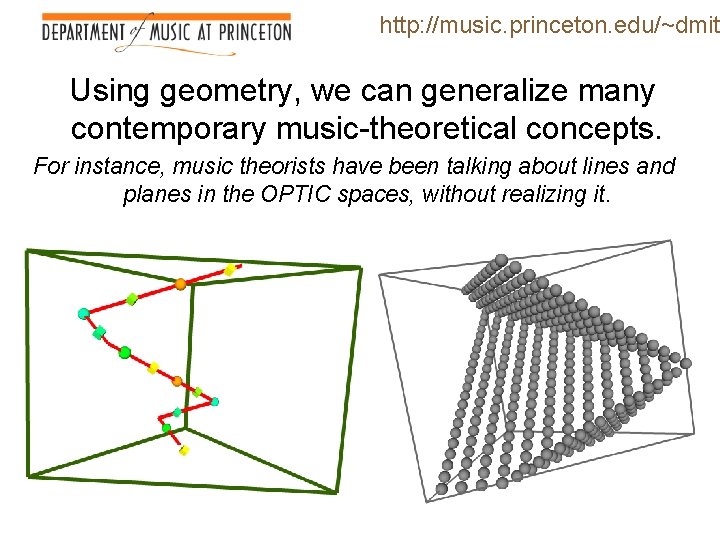

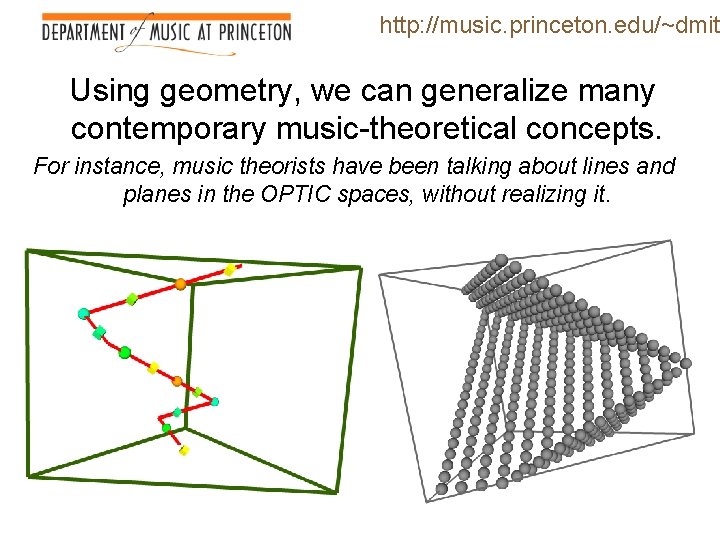

http: //music. princeton. edu/~dmitr Using geometry, we can generalize many contemporary music-theoretical concepts. For instance, music theorists have been talking about lines and planes in the OPTIC spaces, without realizing it.

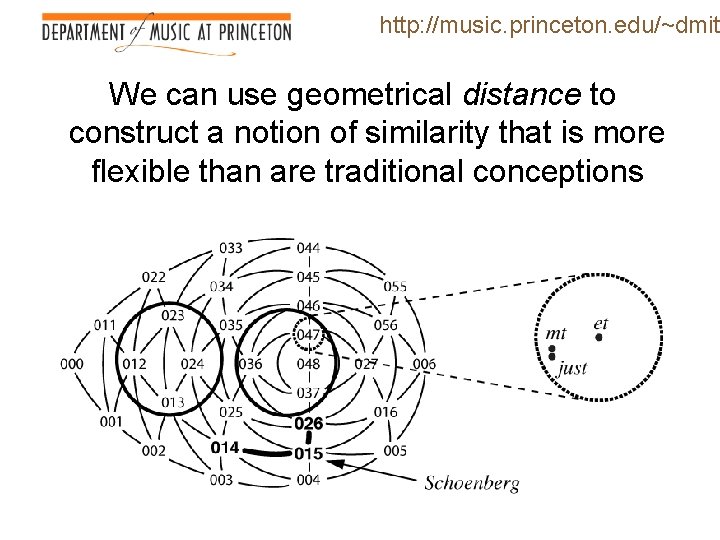

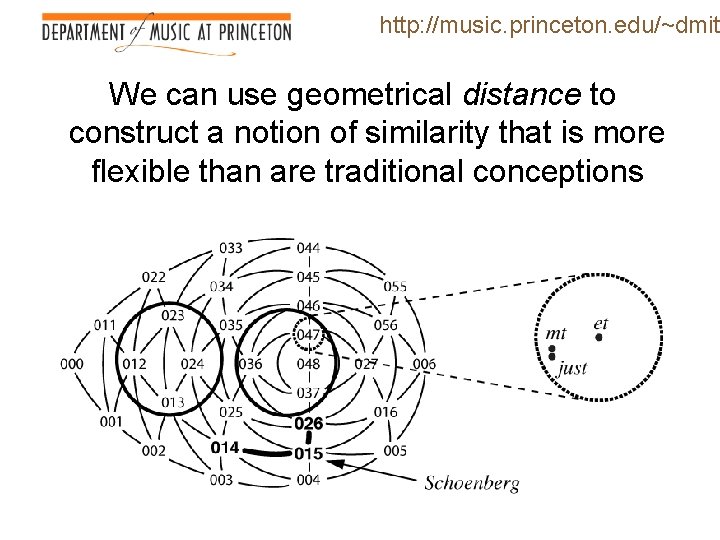

http: //music. princeton. edu/~dmitr We can use geometrical distance to construct a notion of similarity that is more flexible than are traditional conceptions

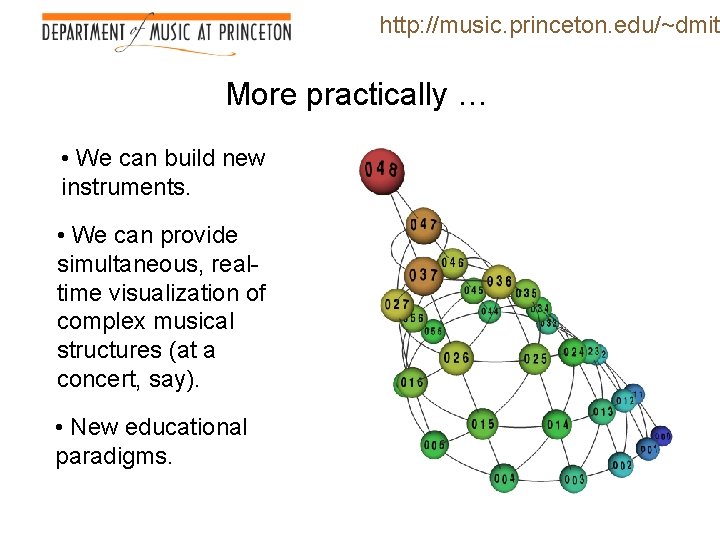

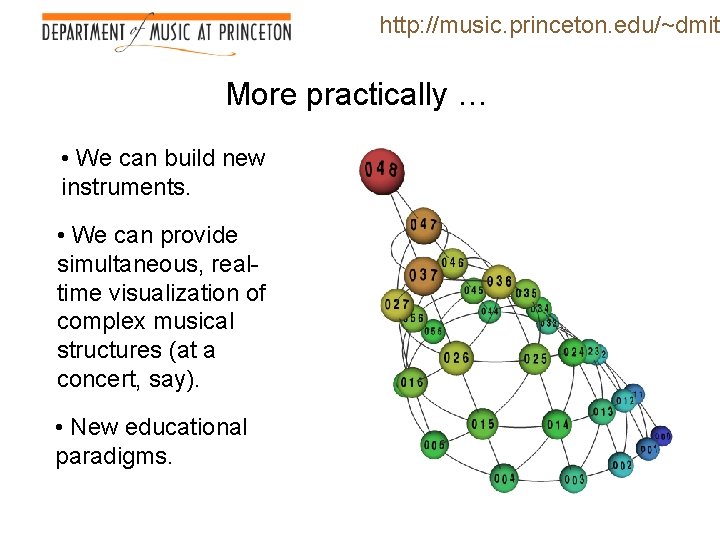

http: //music. princeton. edu/~dmitr More practically … • We can build new instruments. • We can provide simultaneous, realtime visualization of complex musical structures (at a concert, say). • New educational paradigms.

http: //music. princeton. edu/~dmitr Thank you! D. Tymoczko, “The Geometry of Musical Chords. ” Science 313 (2006): 72 -74. C. Callender, I. Quinn, and D. Tymoczko, “Generalized Voice-Leading Spaces. ” Science 320 (2008): 346 -348. BOOK NOW AVAILABLE FOR PREORDER AT AMAZON. COM!!!!