How to approach the passage analysis A passage

![§ [“iamb” = unstressed syllable; “penta” = 5; “meter” = rhythmic pattern] § What? § [“iamb” = unstressed syllable; “penta” = 5; “meter” = rhythmic pattern] § What?](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h/a766e66eb09f0615674fcf62a20a57fd/image-10.jpg)

- Slides: 21

How to approach the passage analysis

§A passage analysis is a task that is designed for you to reveal your familiarity of the play’s plot, your in-depth understanding of the characters and their motivations, the key concerns and ideas that are central to the play and the devices used by Shakespeare to shape meaning and engage the audience.

§ A comprehensive response is one that demonstrates a thorough understanding of context, characters, key concerns and Shakespeare’s use of language. § You cannot do this in a page! Aim to write at least 4 detailed, complex paragraphs.

KNOW CONTEXT: Be able to ‘frame’ the passage specifically by act and scene. KNOW CONTENT: What is the passage about? What is happening? What do we learn? KNOW SIGNIFICANCE: Why is the passage significant? What do we learn about the character(s) and their interaction? What do we learn about human nature? How is this message, lesson or understanding delivered?

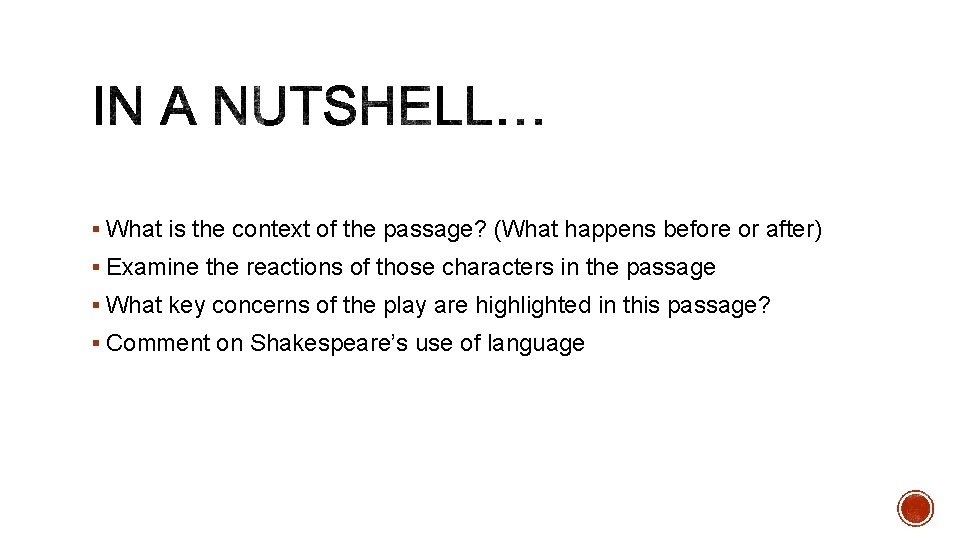

§ Where does the passage appear in the play (give a context for the passage and a brief statement about its significance) § What happens before or after? Demonstrate your familiarity with the entire play. Give examples from the passage § This could be your first paragraph

CHARACTERS § What qualities of the characters are shown? What emotions are expressed? § What developments are evident? Are their any obvious changes in a character’s mindset? § Focus on language features that create character/s. Write about the way language informs us of the situation. Give examples from the passage. § This could be your second paragraph

§ Focus on language features that create ideas in the passage. How do these ideas or themes relate to the plot? This is where you return to the main ideas being communicated in the passages and how this is done. § Think about Shakespeare’s intention, ideas, patterns, comments on human behaviour… § Give examples from the passage. § This could be your third paragraph

§ Now look at the actual words that make up the passage. Turn your focus to the general language features of the passage. § How are the voices presented? What is the rhythm? Think about the punctuation and how it contributes to the rhythm of Shakespeare’s language. § Comment on things such as the vocabulary, the deliberate choice of words, the parts of speech (eg adjectives, adverbs, verbs…), repetition, punctuation, tone (include examples from the passage) § Look for: patterns, contrasts, style-prose/blank verse, rhyming verse (rhyming couplets), iambic pentameter, dramatic irony, foreshadowing, alliteration, allusions figurative language- metaphors, similes, personification, symbolism, antithesis (opposition of ideas ‘Fair is foul…’), listing, staccato sentences. . . § Give examples from the passage.

§Verse § What? Looks like the verses of a poem § The verse in Macbeth falls naturally into two parts: (a) blank verse, that is, unrhymed lines in iambic pentameter; (b) rhymed lines in various metres. §Prose § What? Looks like an ordinary paragraph § Why? For everyday life and ordinary people/commoners don’t speak in special rhymes, it’s practical and relaxed, used in serious letters, to represent madness (verse would be too orderly or regular).

![iamb unstressed syllable penta 5 meter rhythmic pattern What § [“iamb” = unstressed syllable; “penta” = 5; “meter” = rhythmic pattern] § What?](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h/a766e66eb09f0615674fcf62a20a57fd/image-10.jpg)

§ [“iamb” = unstressed syllable; “penta” = 5; “meter” = rhythmic pattern] § What? Rhythmic pattern of 5 iambs per line (can be rhyming or unrhyming)

§ What? rhyming couplets (often a, a, b, b, c, c) § Why? For advice, songs, prologues, epilogues, choruses, imaginary plays within plays, supernatural § COUPLETS – a pair of successive lines of verse

§ What? Unrhyming verse (usually iambic pentameter) § Why? Wide range of uses, passionate, refined characters speak in blank verse

§ What? Looks like an ordinary paragraph § Why? For everyday life and ordinary people/commoners don’t speak in special rhymes, it’s practical and relaxed, used in serious letters, to represent madness (verse would be too orderly or regular).

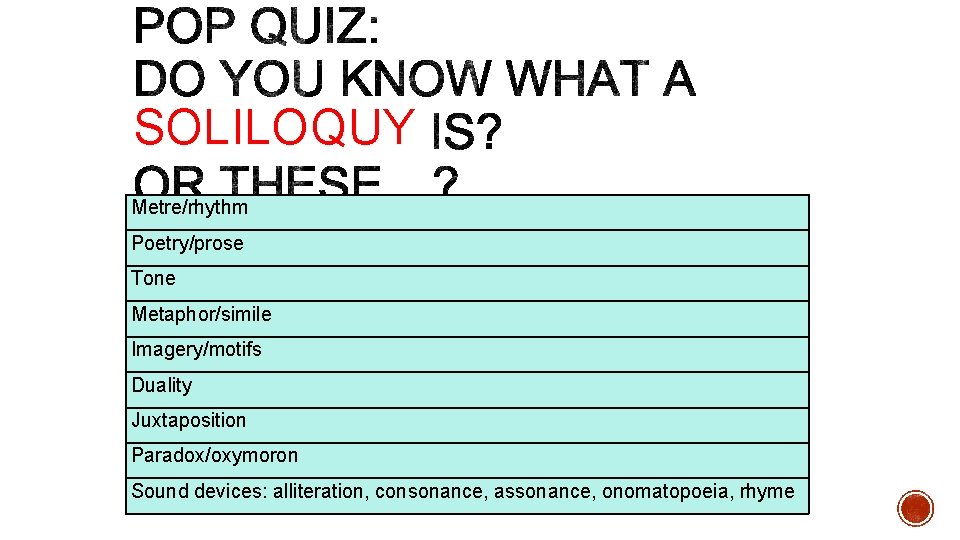

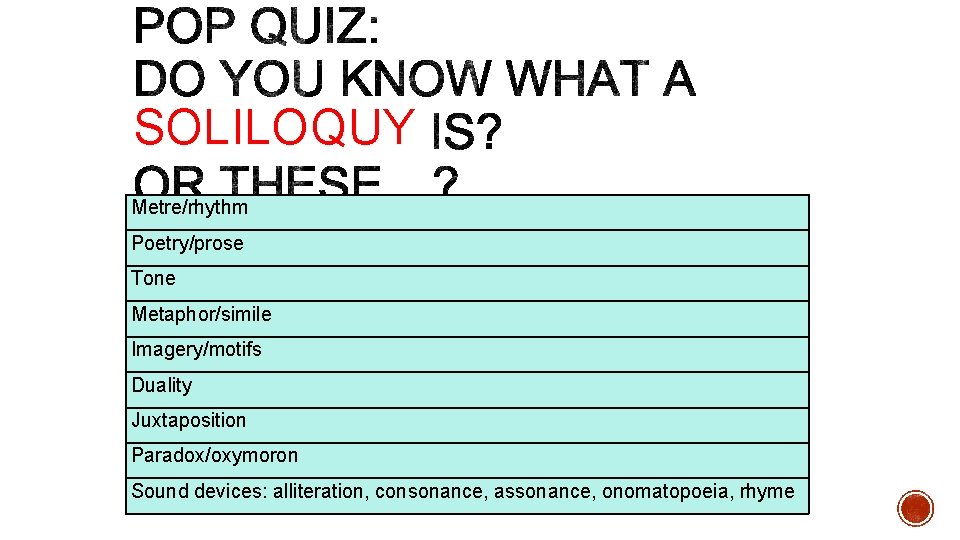

SOLILOQUY Metre/rhythm Poetry/prose Tone Metaphor/simile Imagery/motifs Duality Juxtaposition Paradox/oxymoron Sound devices: alliteration, consonance, assonance, onomatopoeia, rhyme

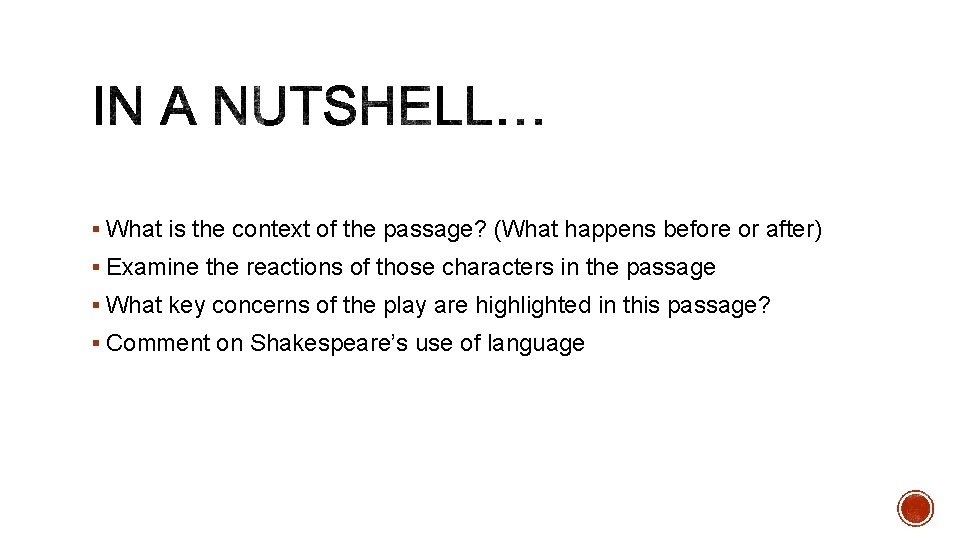

§ What is the context of the passage? (What happens before or after) § Examine the reactions of those characters in the passage § What key concerns of the play are highlighted in this passage? § Comment on Shakespeare’s use of language

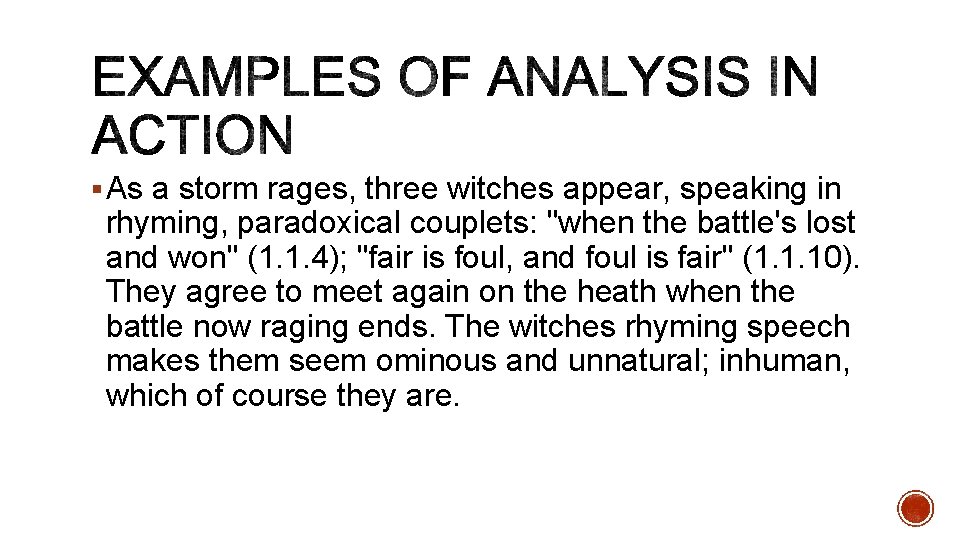

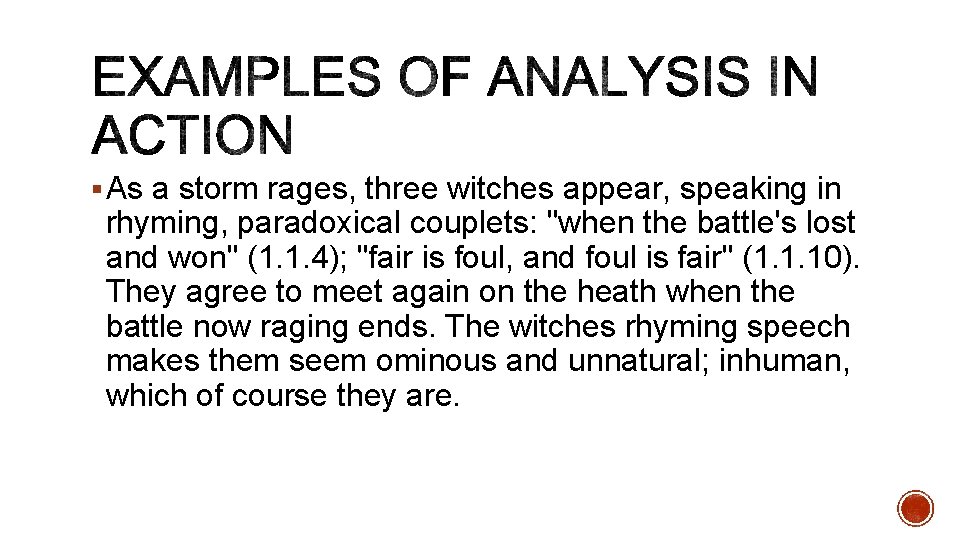

§ As a storm rages, three witches appear, speaking in rhyming, paradoxical couplets: "when the battle's lost and won" (1. 1. 4); "fair is foul, and foul is fair" (1. 1. 10). They agree to meet again on the heath when the battle now raging ends. The witches rhyming speech makes them seem ominous and unnatural; inhuman, which of course they are.

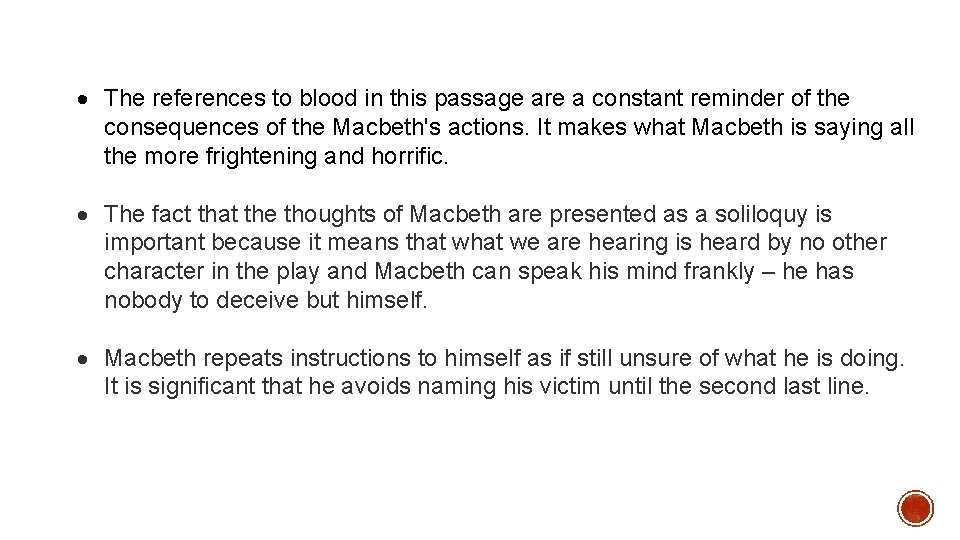

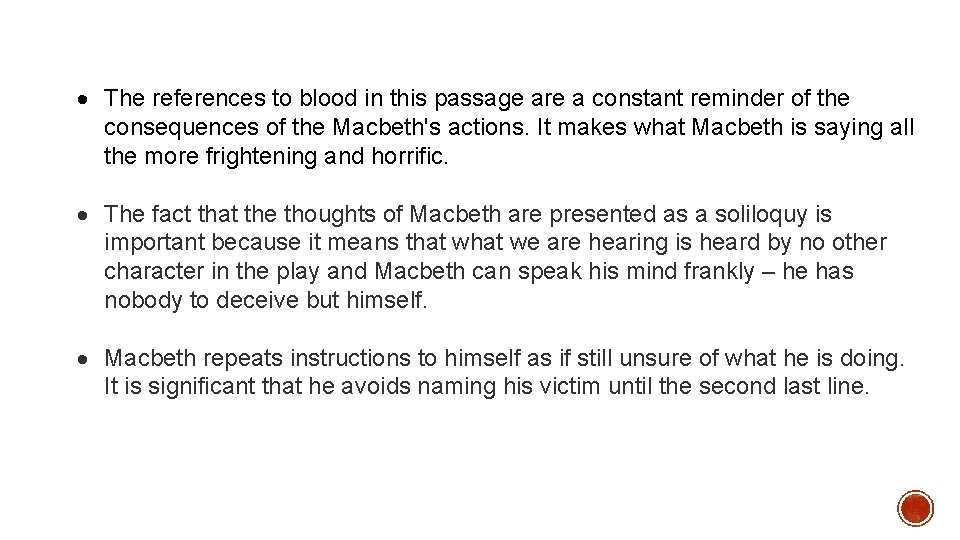

The references to blood in this passage are a constant reminder of the consequences of the Macbeth's actions. It makes what Macbeth is saying all the more frightening and horrific. The fact that the thoughts of Macbeth are presented as a soliloquy is important because it means that we are hearing is heard by no other character in the play and Macbeth can speak his mind frankly – he has nobody to deceive but himself. Macbeth repeats instructions to himself as if still unsure of what he is doing. It is significant that he avoids naming his victim until the second last line.

The dagger itself with its suggestive movements and drops of blood is an image of Macbeth's troubled conscience which he cannot 'clutch' or be sure about. The 'heatoppressèd brain' which creates the elusive dagger is the same brain that is needed for the 'heat of deeds'. In the imagery of witchcraft and murder the concentration is on the sacrifice of innocence by a secret and ruthless power. The only colours present in the soliloquy are those of darkness and blood. The structure favoured by Shakespeare in this soliloquy reveals further tension in Macbeth's mind. The opening lines are marked by questions, exclamations, qualifications and repetitions, all suggesting uncertainty and anxiety. In the middle parts, longer sentences with lots of adjectives create a sense of deliberation and suspense as well as intensity. The final part seems to offer resolution to the questions and doubts raised at the beginning that perhaps there is something mechanical in it – that Macbeth has not set his mind at rest.

§ Through the use of emotive language, these monologue extracts reveal Benedick and Beatrice’s thoughts to the audience, as they process the news that they are loved by the other. Both pieces begin with them questioning the validity and truth of the news they just heard, showing the audience their feelings of confusion or, in Beatrice’s case surprise, asking, “Can this be true? ” The characters’ use of affectionate and praising adjectives such as “fair”, “wise” and “loving” when describing their current feelings towards the other also reveal to the audience their affectionate and loving feelings, whether they are aware of them or not. The language that is employed by Benedick and Beatrice during their revelations regarding love show the audience in great detail their new found feelings of love, with Benedick stating that he will be “horribly in love with her”, showing both his surprise and previous resentment of love, as well as his new found appreciation for Beatrice. Similarly, the line said by Beatrice “I will requite thee, taming my wild heart to thy loving hand” reveals not only her love for Benedick, but also her new desire to appear more attractive and submissive in order to secure him as a husband. The way the characters talk themselves through their new love towards each other and arrive at a conclusion as to how they will interpret and act on the words they overhead further shows the audience their thoughts and feelings of love and adoration of one another. Beatrice states that her “kindness”, which she has never shown to Benedick before, will “intice” him to “bind [their] loves up in a holy band”, revealing to the audience that she now wants to marry Benedick, and will act kind towards him to cement his love for her. Benedick’s announcement that he “did not think [he] should live till [he] were married” also shows the audience his thoughts of marriage, now that he believes Beatrice to love him.

§ This passage which is taken from William Shakespeare’s Macbeth and appears in Act 2 Scene 1 is important because it conveys to the audience Macbeth’s fluctuating state of mind. Prior to this passage, the witches have told Macbeth of the prophecy whereby he will be crowned king, and upon sending Lady Macbeth a letter the two have conspired to kill King Duncan so as to ensure his ascension to the Scottish throne. On stage this soliloquy helps reveal Macbeth’s deteriorating mind, yet his growing determination to fulfil the prophecy at any cost. § The first 12 lines of the soliloquy are concerned with sense perception and whether or not Macbeth is actually seeing a dagger in front of him. He wonders if it is a ‘false creation’ of a ‘heat-oppressed brain’. By using the adjective ‘heat-oppressed’ the audience is encouraged to consider what elements are causing such a hot temperament, elements such as his greed, ambition and consideration of regicide. Shakespeare’s deliberate use of three questions in this section of the soliloquy serves to highlight not only the literal questioning of the dagger itself, but whether or not he is able to ‘clutch’ that which ‘marshall’st’ him towards killing Duncan. The questioning of sense perception and the ‘fatal vision’ before him is important because it foreshadows both Lady Macbeth and Macbeth’s eventual descent into delusion where Lady Macbeth questions the blood on her hands and Macbeth sees Banquo’s ghost at dinner. ‘Come, let me clutch thee’ is declarative sentence about Macbeth because it reveals his determination to take fate into his own hands. That staccato sentence appears amongst more elongated sentences highlighting his wavering mindset. Also drawing attention to whether or not he is able to actually carry through with his darker deed. The audience also become aware of an irony when Macbeth labels the dagger as a ‘fatal vision’ as the actions he is about to commit lead to his fatal outcome. § Upon the sounding of a bell, Macbeth is resigned to what ‘is done’ and he hints at a higher purpose that ‘invites’ and ‘summons’ him to commit acts that will seal his fate. Ending the passage with the dichotomy of ‘heaven’ or ‘hell’ leaving the audience to ponder which side Macbeth’s action will fall. § §

Macbeth’s soliloquy then turns to consider the apparent ‘gouts of blood’ on the imagined ‘blade’ before him suggesting to the audience that Macbeth is more committed to the ‘bloody business’ of murdering Duncan. For an Elizabethan audience the act of regicide would call into question the Great Chain of Being (whereby killing god’s appointed king/representative on earth would have catastrophic for both the social or natural order). Such a turmoil is then explored by Macbeth when he states ‘nature seems dead’ and is furthered by the verb choice of ‘abused’ in relation to the ‘wicked dreams’ that ‘witchcraft celebrates’. The inversion of natural order and the inclusion of the supernatural would have been engrossing for the Elizabeth audiences and King James for whom the play was written (who was himself entranced by the supernatural). It is interesting to note that Macbeth makes mention of ‘wicked dreams’ and ‘curtain’d sleep’ hinting at a concern that will develop later in the play; where both Macbeth and Lady Macbeth will experience troubles in their sleep. Macbeth’s likening of himself to ‘Tarquin’ and the ‘wolf’ who ‘howls’ ‘towards his design’ which is to seize throne violently magnifies the situation and hints at the more sinister intentions that Macbeth harbours also hinting at the later tyranny that Scotland will later experience.