How Much Will the Climate Warm Alex Hall

- Slides: 32

How Much Will the Climate Warm? Alex Hall and Xin Qu UCLA Department of Atmospheric and Oceanic Sciences UCLA Institute of the Environmental Science Colloquium

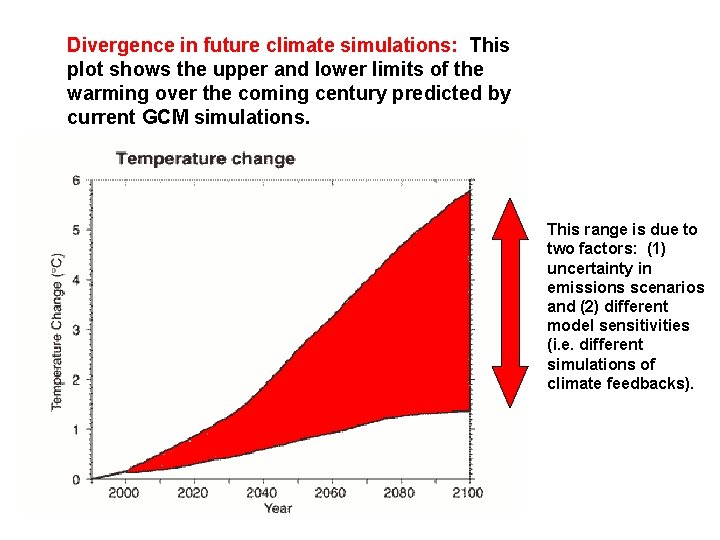

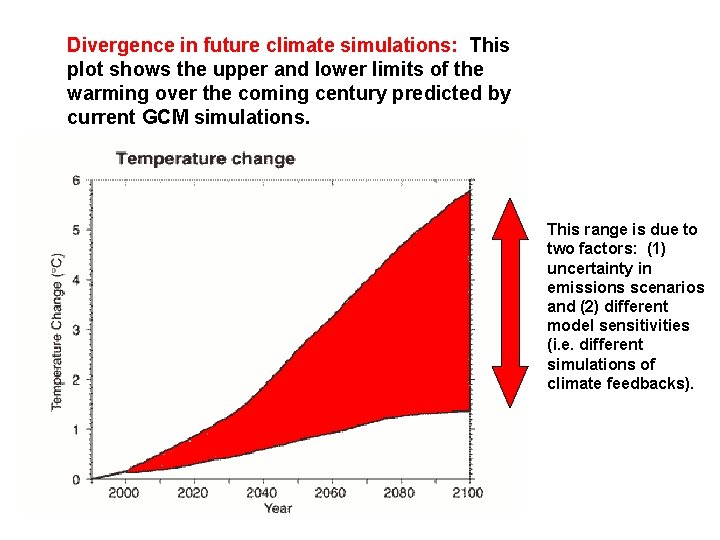

Divergence in future climate simulations: This plot shows the upper and lower limits of the warming over the coming century predicted by current GCM simulations. This range is due to two factors: (1) uncertainty in emissions scenarios and (2) different model sensitivities (i. e. different simulations of climate feedbacks).

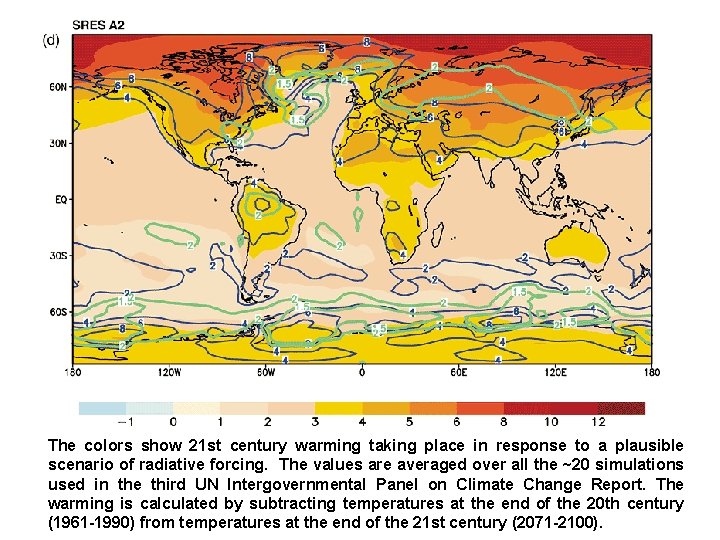

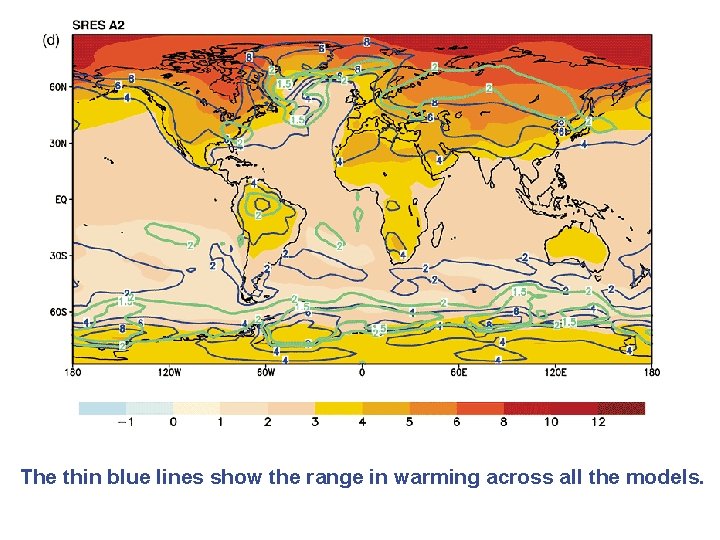

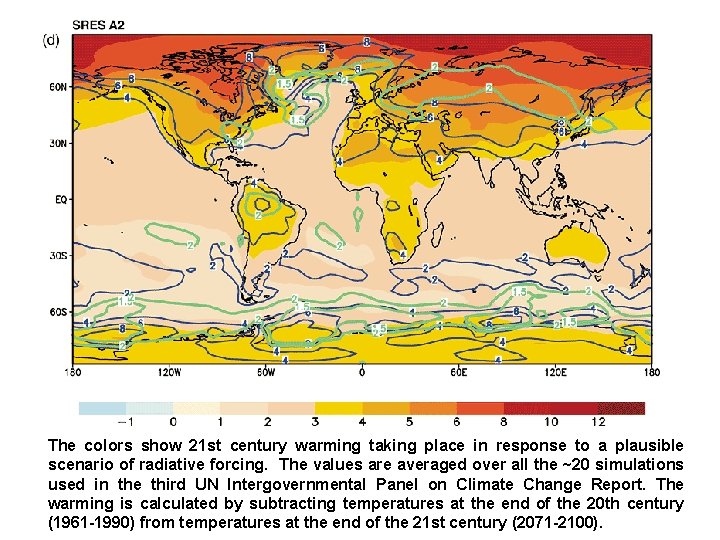

The colors show 21 st century warming taking place in response to a plausible scenario of radiative forcing. The values are averaged over all the ~20 simulations used in the third UN Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change Report. The warming is calculated by subtracting temperatures at the end of the 20 th century (1961 -1990) from temperatures at the end of the 21 st century (2071 -2100).

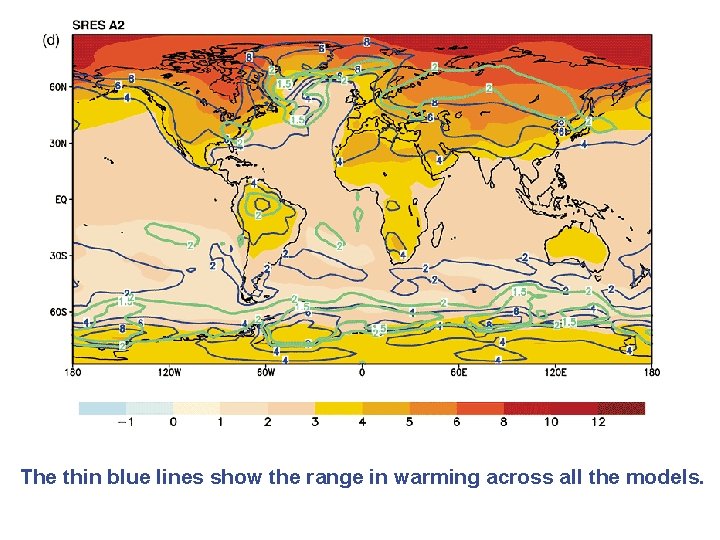

The thin blue lines show the range in warming across all the models.

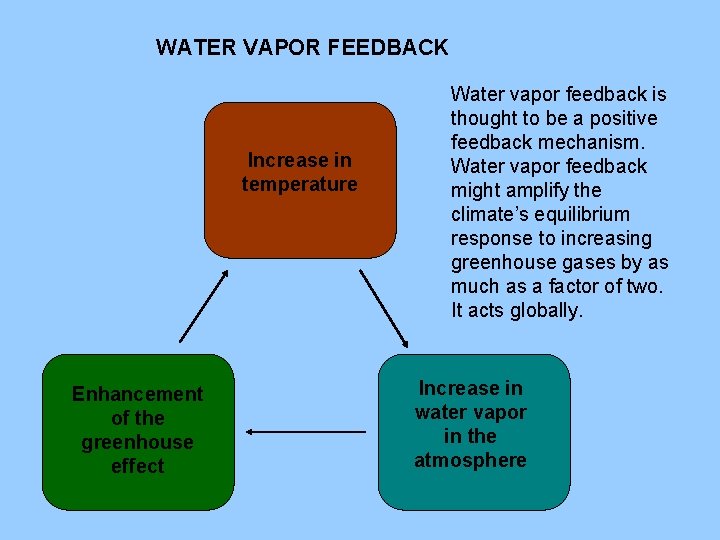

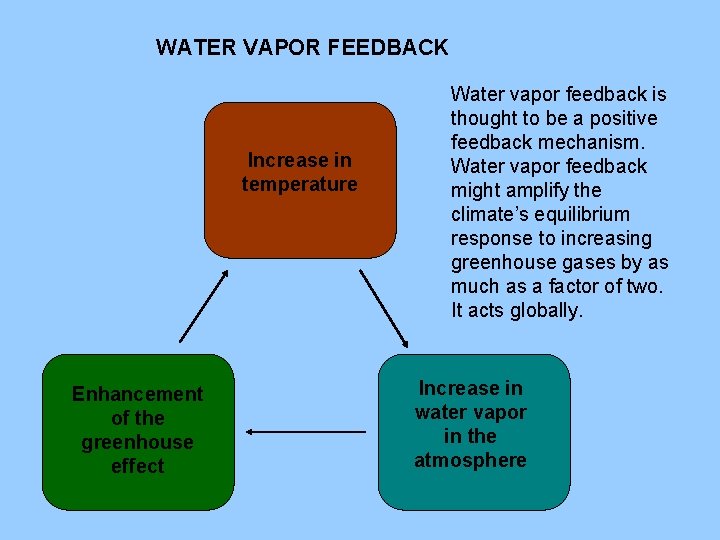

WATER VAPOR FEEDBACK Increase in temperature Enhancement of the greenhouse effect Water vapor feedback is thought to be a positive feedback mechanism. Water vapor feedback might amplify the climate’s equilibrium response to increasing greenhouse gases by as much as a factor of two. It acts globally. Increase in water vapor in the atmosphere

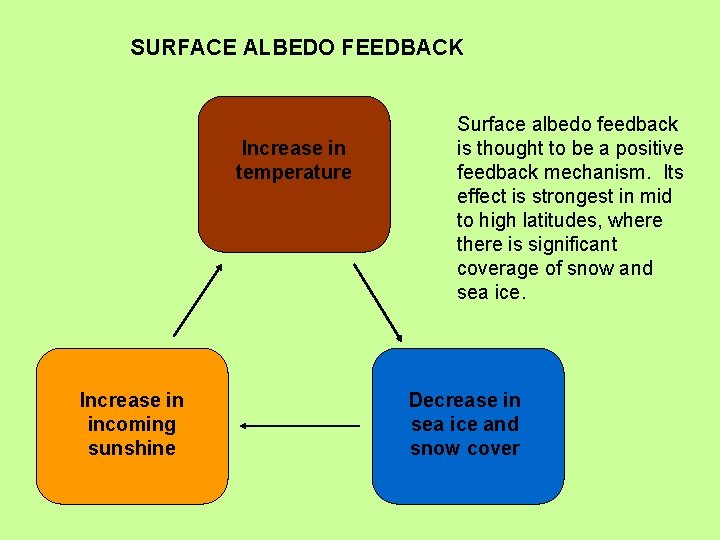

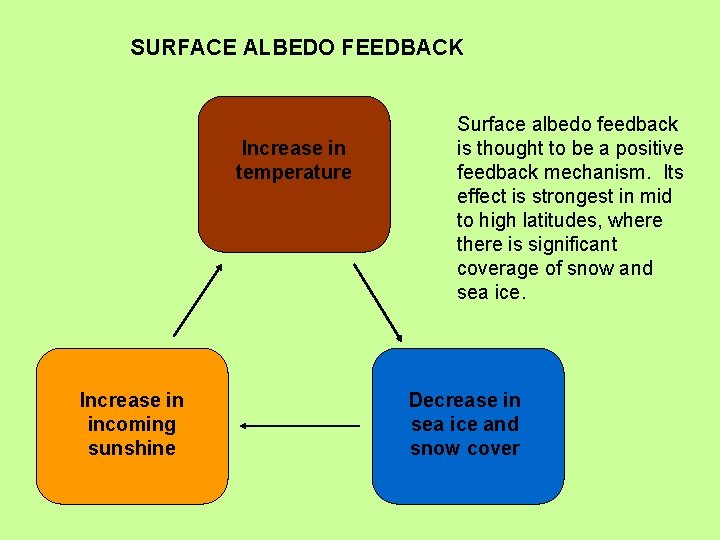

SURFACE ALBEDO FEEDBACK Increase in temperature Increase in incoming sunshine Surface albedo feedback is thought to be a positive feedback mechanism. Its effect is strongest in mid to high latitudes, where there is significant coverage of snow and sea ice. Decrease in sea ice and snow cover

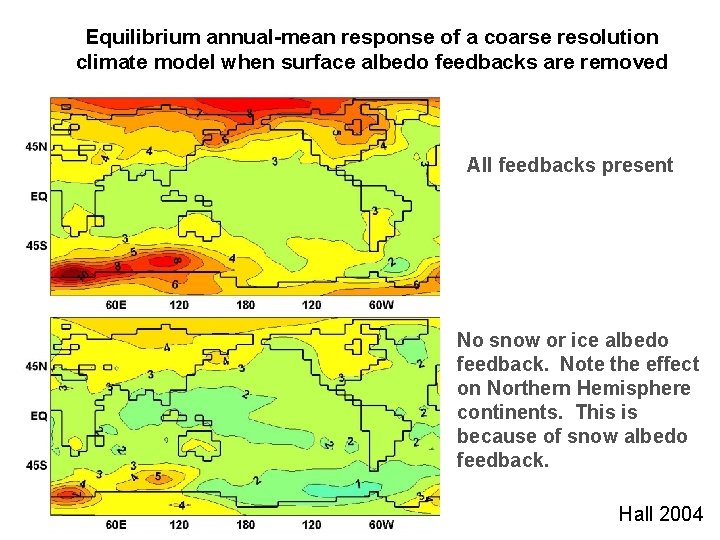

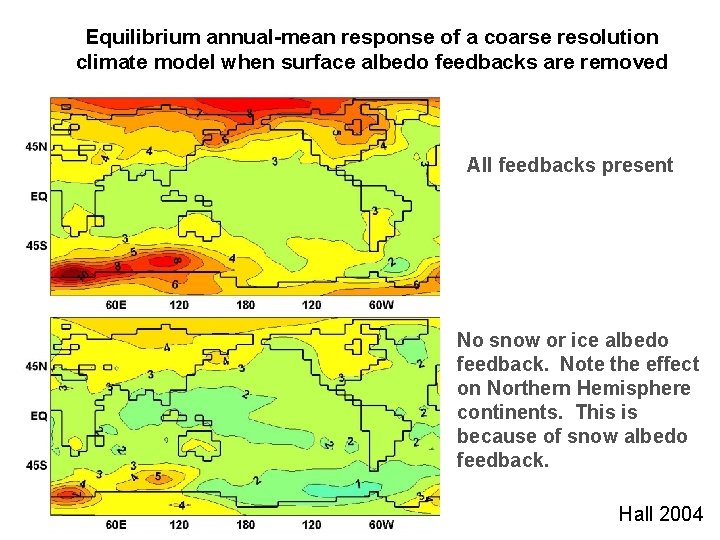

Equilibrium annual-mean response of a coarse resolution climate model when surface albedo feedbacks are removed All feedbacks present No snow or ice albedo feedback. Note the effect on Northern Hemisphere continents. This is because of snow albedo feedback. Hall 2004

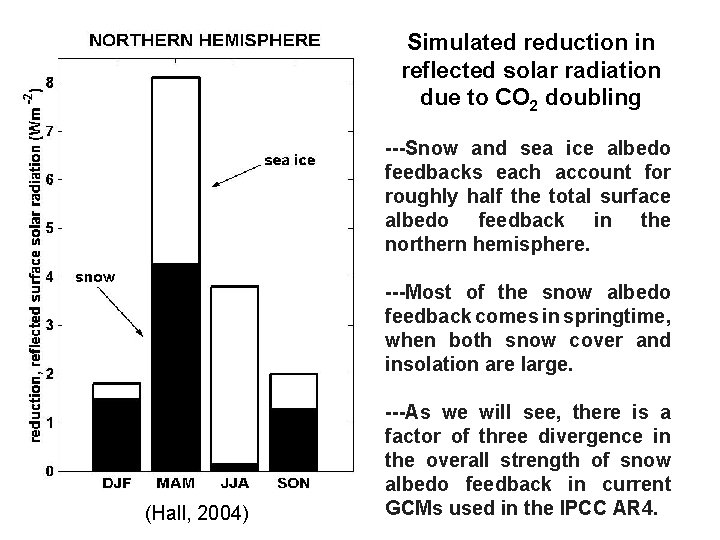

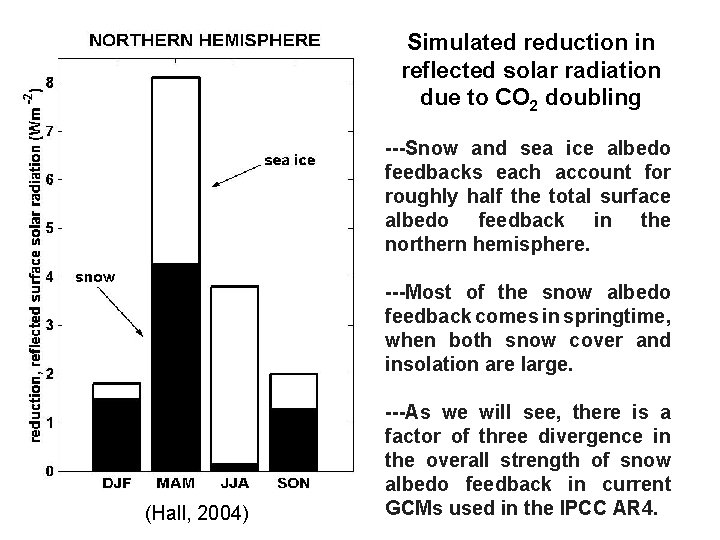

Simulated reduction in reflected solar radiation due to CO 2 doubling ---Snow and sea ice albedo feedbacks each account for roughly half the total surface albedo feedback in the northern hemisphere. ---Most of the snow albedo feedback comes in springtime, when both snow cover and insolation are large. (Hall, 2004) ---As we will see, there is a factor of three divergence in the overall strength of snow albedo feedback in current GCMs used in the IPCC AR 4.

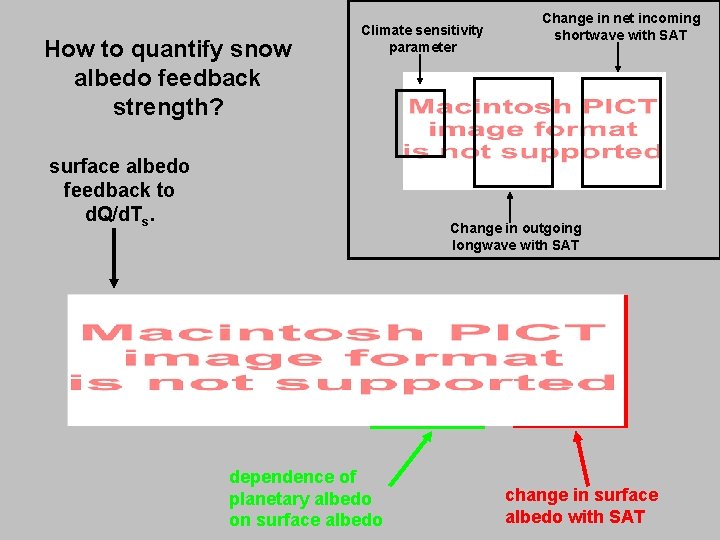

classical climate sensitivity framework climate sensitivity parameter change in net incoming shortwave with SAT change in outgoing longwave with SAT

How to quantify snow albedo feedback strength? Climate sensitivity parameter surface albedo feedback to d. Q/d. Ts. Change in net incoming shortwave with SAT Change in outgoing longwave with SAT dependence of planetary albedo on surface albedo change in surface albedo with SAT

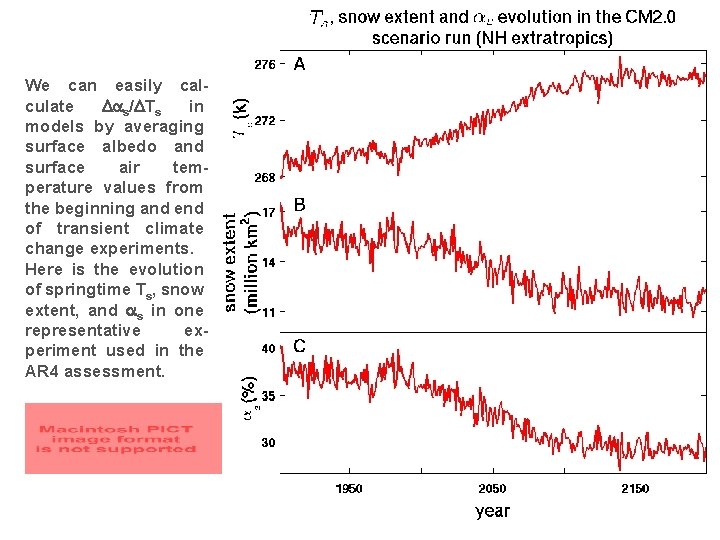

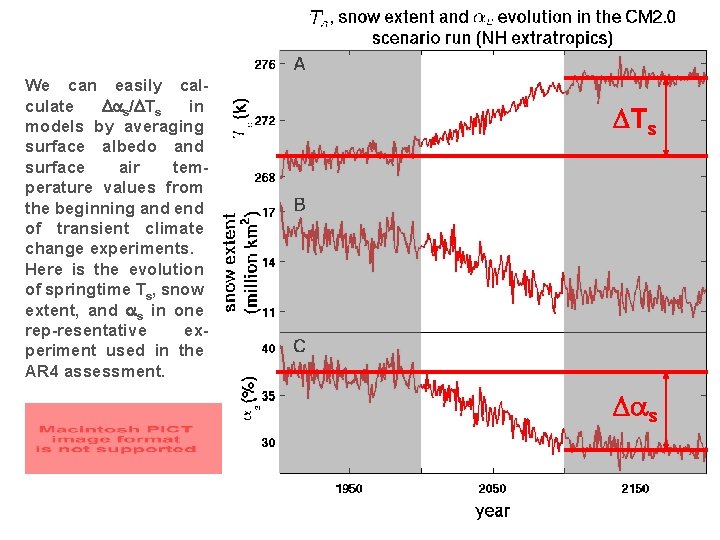

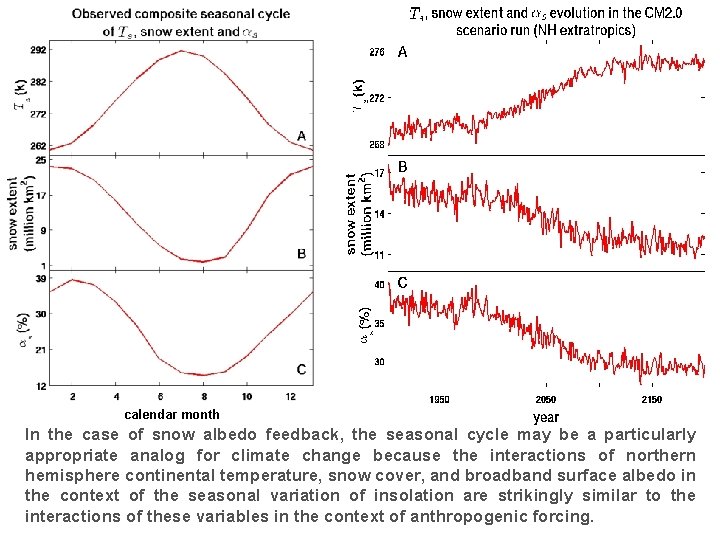

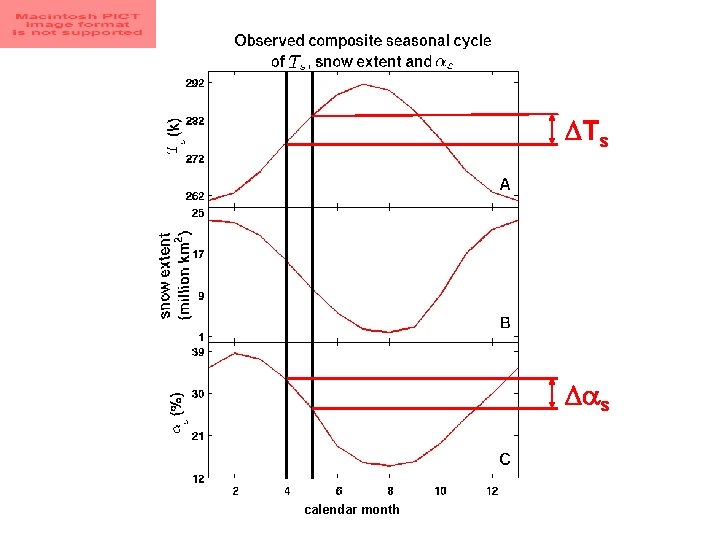

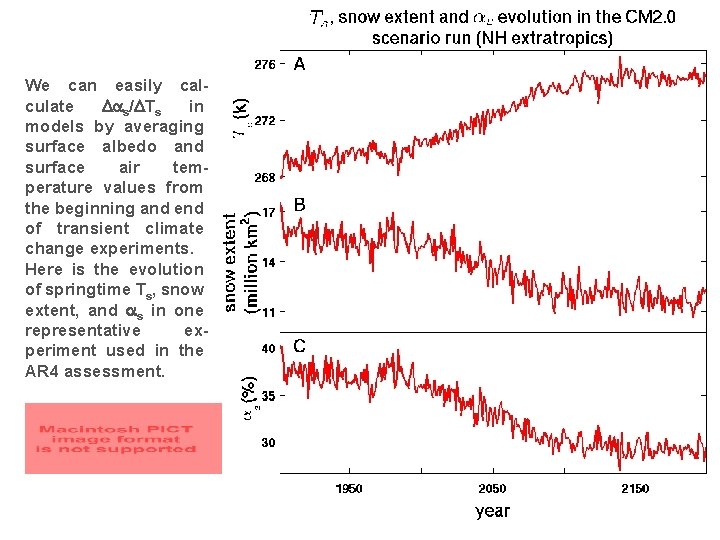

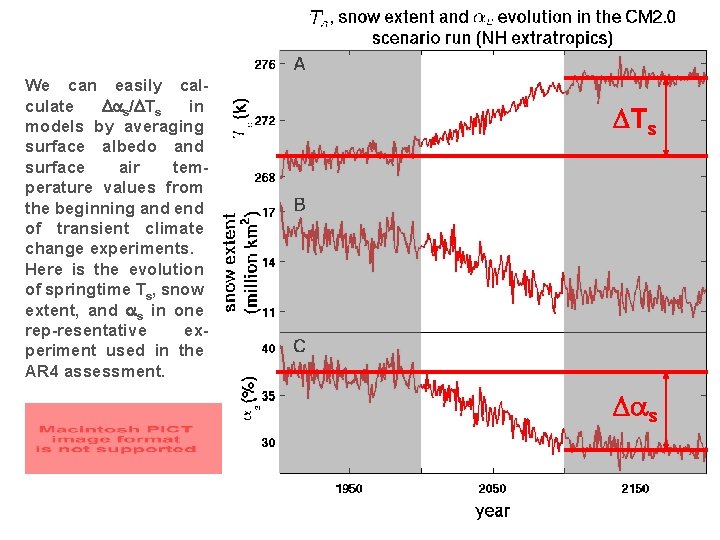

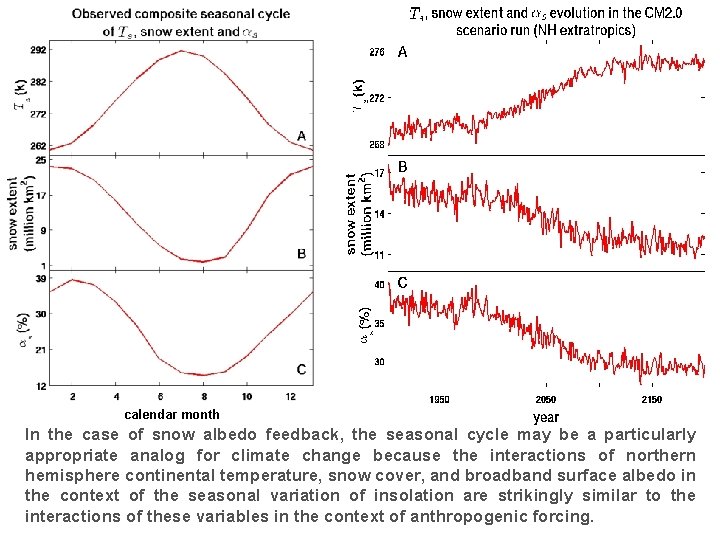

We can easily calculate s/ Ts in models by averaging surface albedo and surface air temperature values from the beginning and end of transient climate change experiments. Here is the evolution of springtime Ts, snow extent, and s in one representative experiment used in the AR 4 assessment.

We can easily calculate s/ Ts in models by averaging surface albedo and surface air temperature values from the beginning and end of transient climate change experiments. Here is the evolution of springtime Ts, snow extent, and s in one rep-resentative experiment used in the AR 4 assessment. Ts s

The sensitivity of surface albedo to surface air temperature in land areas poleward of 30 N exhibits a three-fold spread in the current generation of climate models. This is a major source of spread in projections of future climate in the region.

HOW TO REDUCE THE SPREAD? The work of Tsushima et al. (2005) and Knutti and Meehl (2005) suggests the seasonal cycle of temperature may be subject to the same climate feedbacks as anthropogenic warming. Therefore comparing simulated feedbacks in the context of the seasonal cycle to observations may offer a means of circumventing a central difficulty of future climate research: It is impossible to evaluate future climate feedbacks against observations that do not exist.

calendar month In the case of snow albedo feedback, the seasonal cycle may be a particularly appropriate analog for climate change because the interactions of northern hemisphere continental temperature, snow cover, and broadband surface albedo in the context of the seasonal variation of insolation are strikingly similar to the interactions of these variables in the context of anthropogenic forcing.

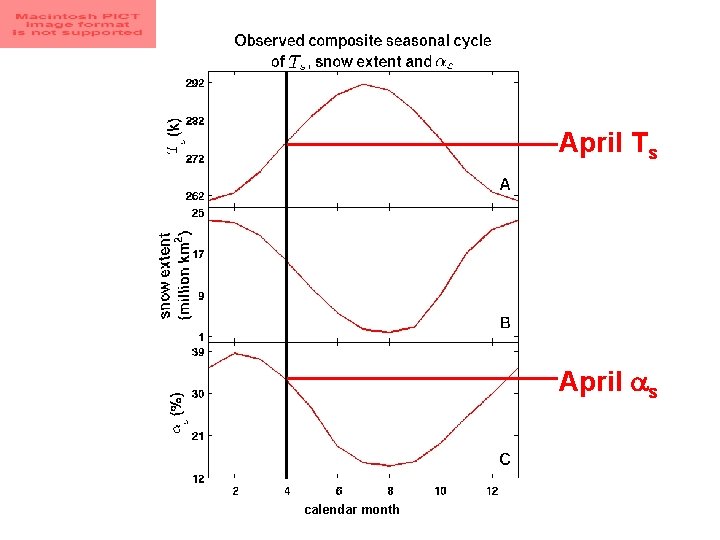

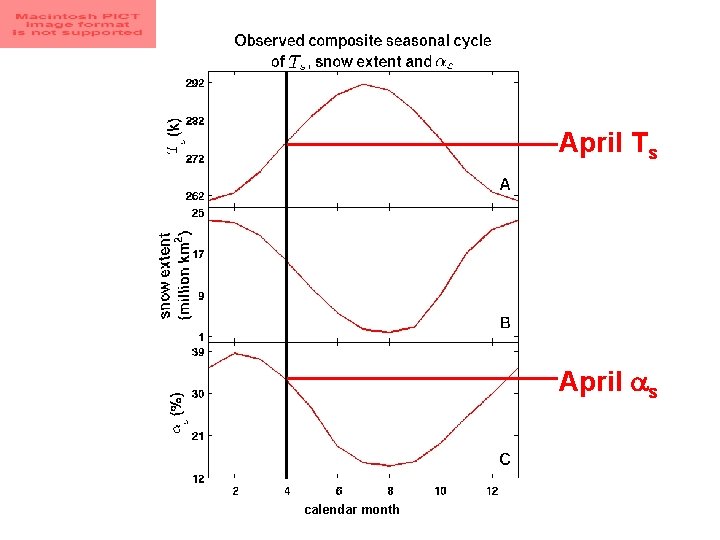

April Ts April s calendar month

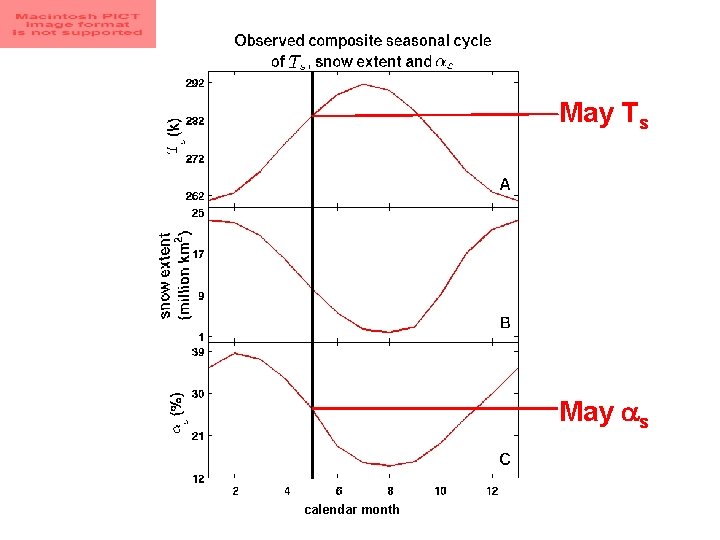

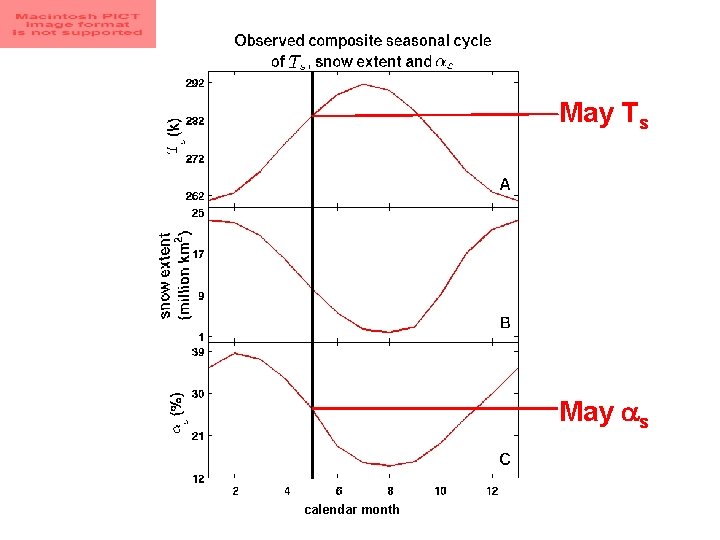

May Ts May s calendar month

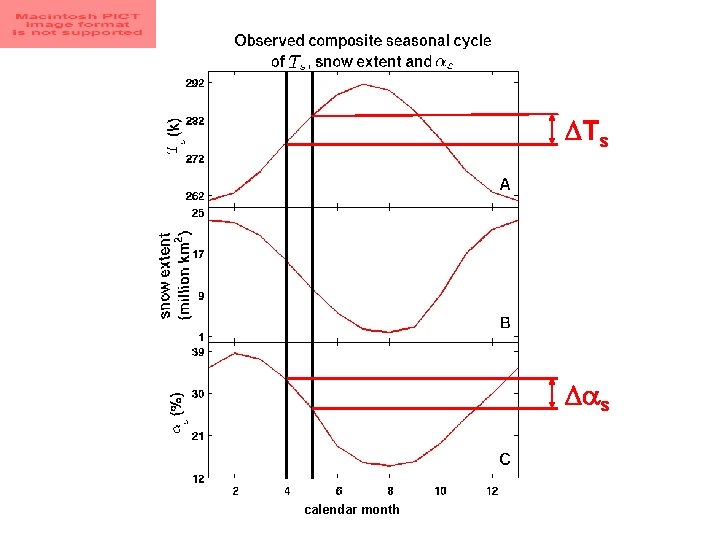

Ts s calendar month

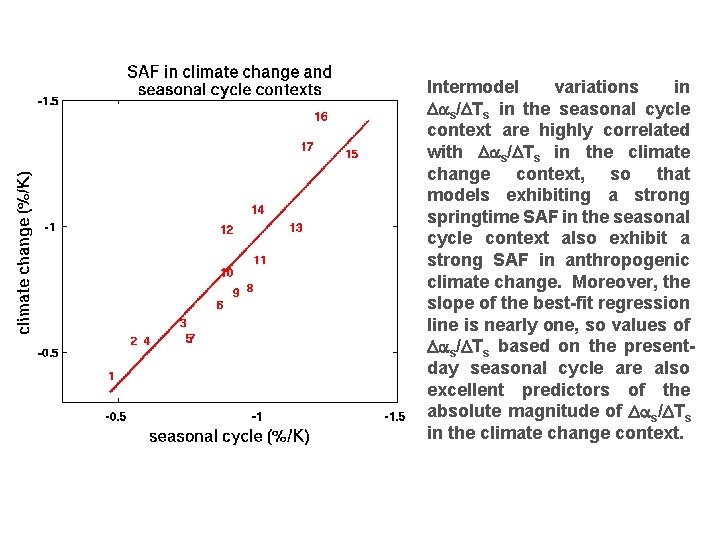

So we can calculate springtime values of s/ Ts for climate change and the current seasonal cycle. What is the relationship between this feedback parameter in these two contexts?

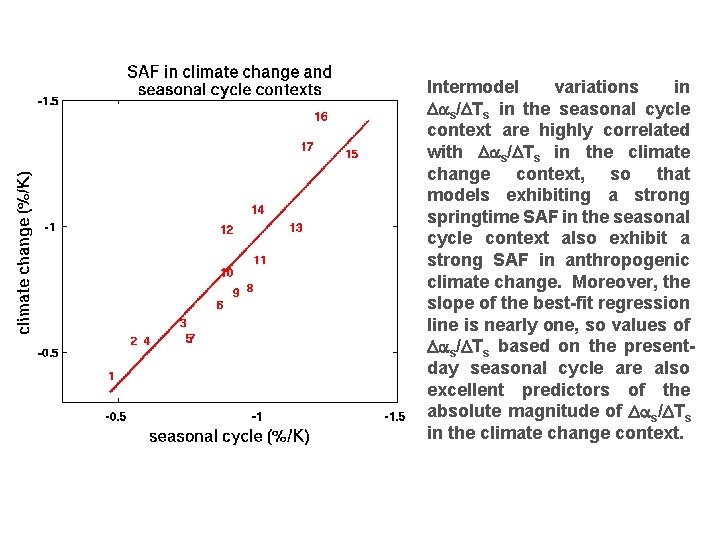

Intermodel variations in s/ Ts in the seasonal cycle context are highly correlated with s/ Ts in the climate change context, so that models exhibiting a strong springtime SAF in the seasonal cycle context also exhibit a strong SAF in anthropogenic climate change. Moreover, the slope of the best-fit regression line is nearly one, so values of s/ Ts based on the presentday seasonal cycle are also excellent predictors of the absolute magnitude of s/ Ts in the climate change context.

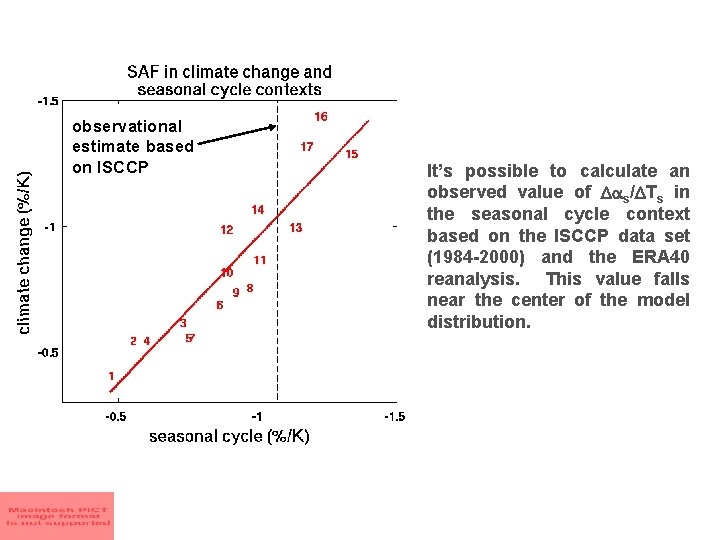

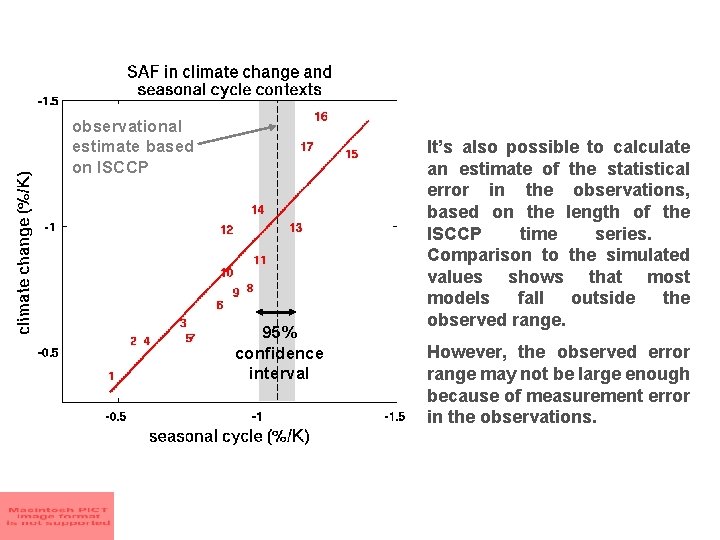

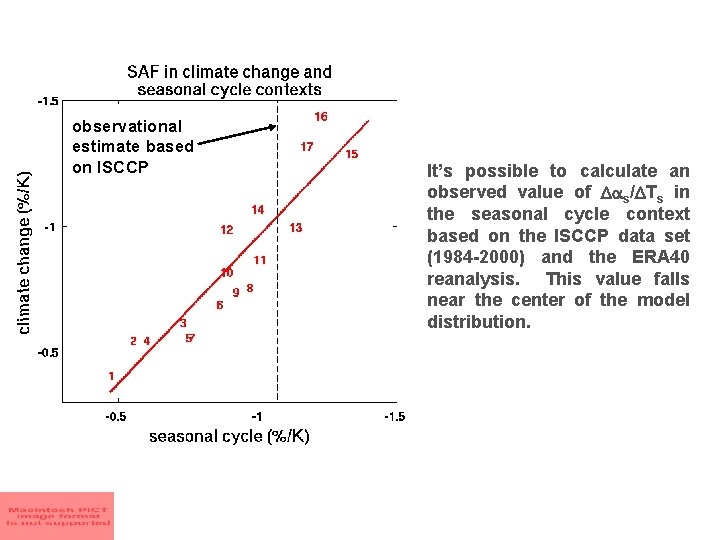

observational estimate based on ISCCP It’s possible to calculate an observed value of s/ Ts in the seasonal cycle context based on the ISCCP data set (1984 -2000) and the ERA 40 reanalysis. This value falls near the center of the model distribution.

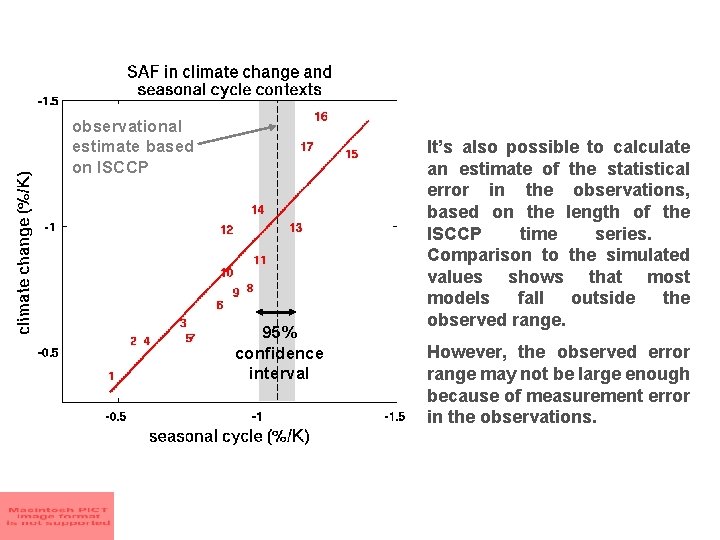

observational estimate based on ISCCP 95% confidence interval It’s also possible to calculate an estimate of the statistical error in the observations, based on the length of the ISCCP time series. Comparison to the simulated values shows that most models fall outside the observed range. However, the observed error range may not be large enough because of measurement error in the observations.

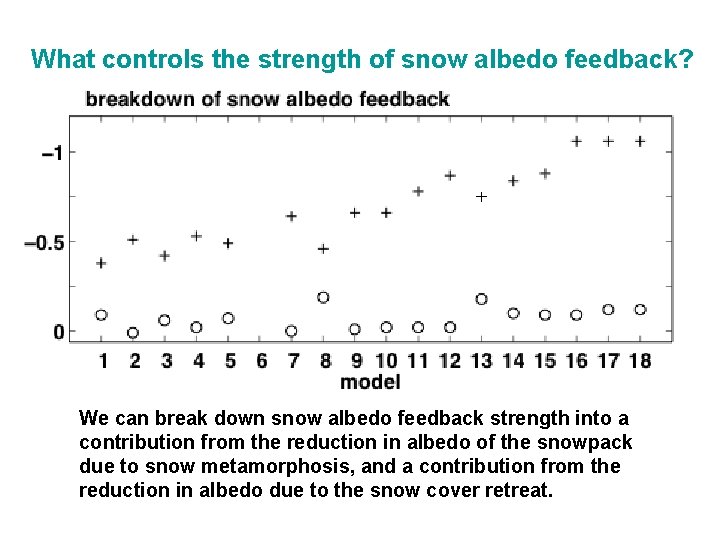

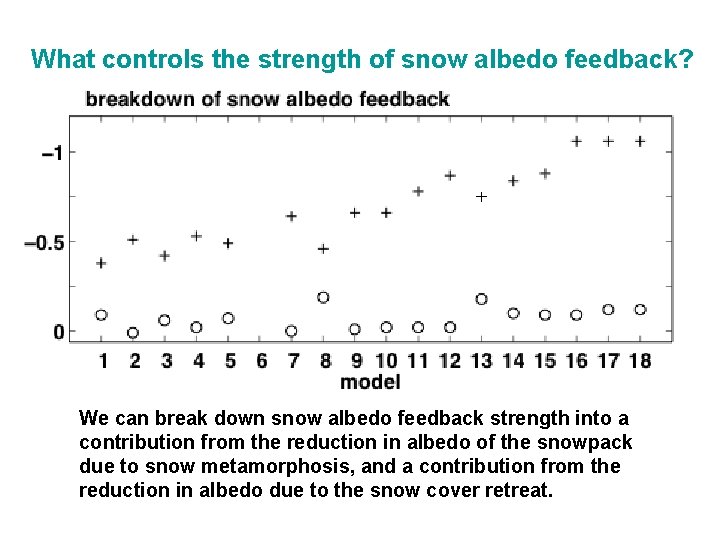

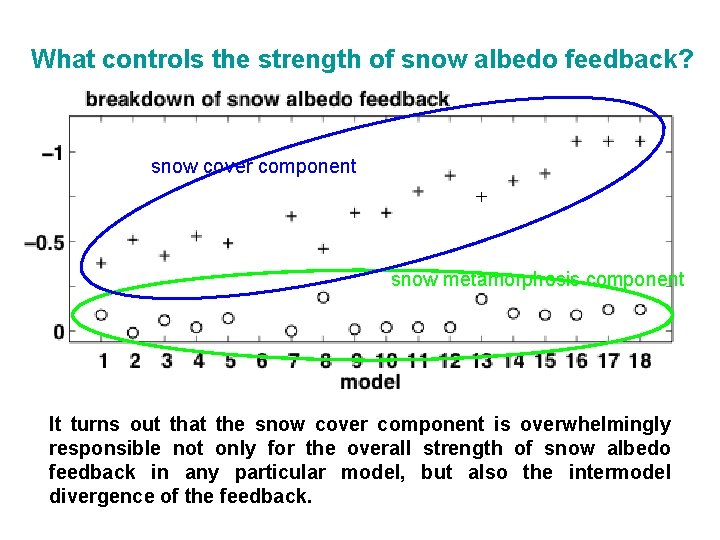

What controls the strength of snow albedo feedback? We can break down snow albedo feedback strength into a contribution from the reduction in albedo of the snowpack due to snow metamorphosis, and a contribution from the reduction in albedo due to the snow cover retreat.

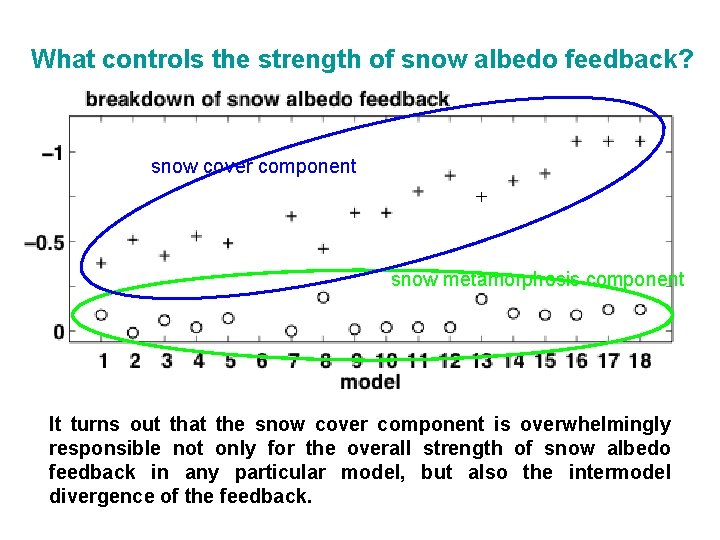

What controls the strength of snow albedo feedback? snow cover component snow metamorphosis component It turns out that the snow cover component is overwhelmingly responsible not only for the overall strength of snow albedo feedback in any particular model, but also the intermodel divergence of the feedback.

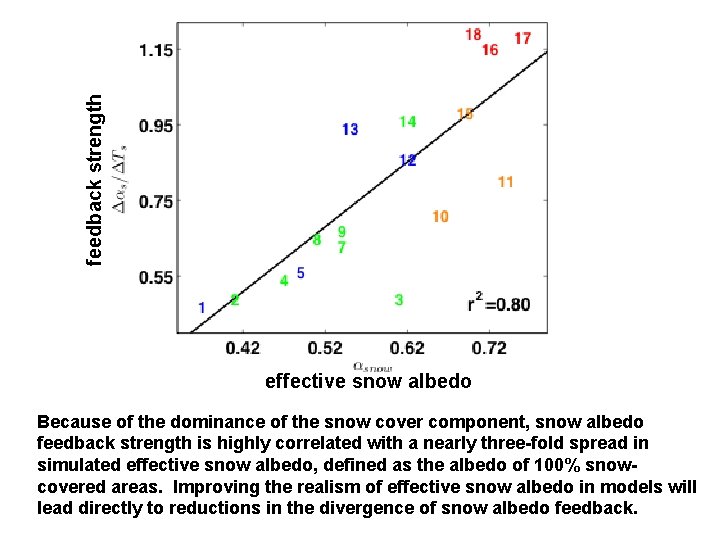

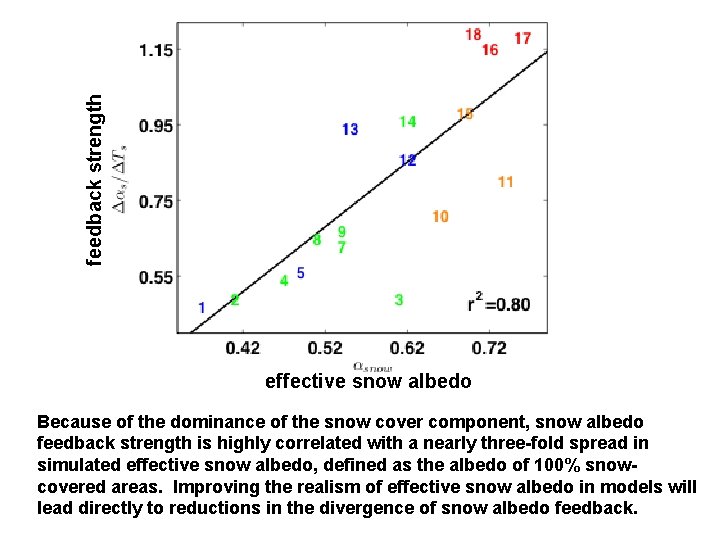

feedback strength effective snow albedo Because of the dominance of the snow cover component, snow albedo feedback strength is highly correlated with a nearly three-fold spread in simulated effective snow albedo, defined as the albedo of 100% snowcovered areas. Improving the realism of effective snow albedo in models will lead directly to reductions in the divergence of snow albedo feedback.

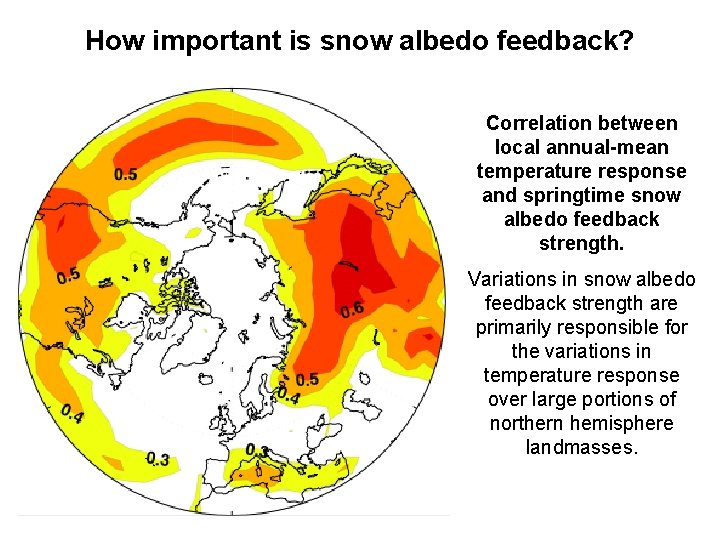

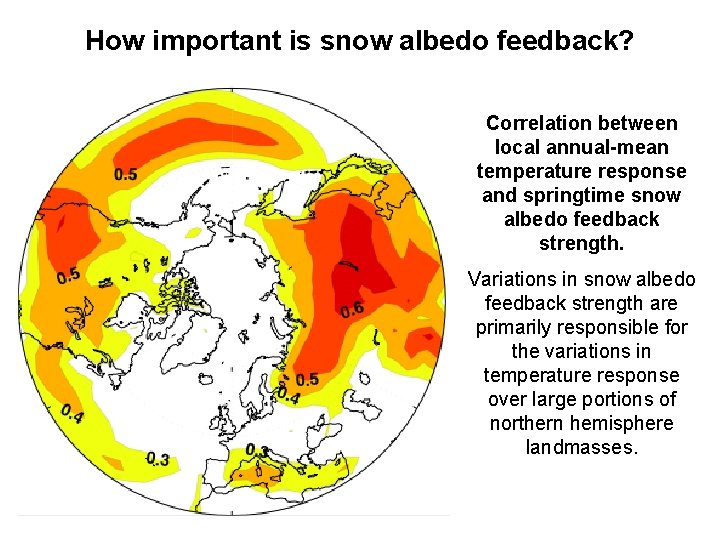

How important is snow albedo feedback? Correlation between local annual-mean temperature response and springtime snow albedo feedback strength. Variations in snow albedo feedback strength are primarily responsible for the variations in temperature response over large portions of northern hemisphere landmasses.

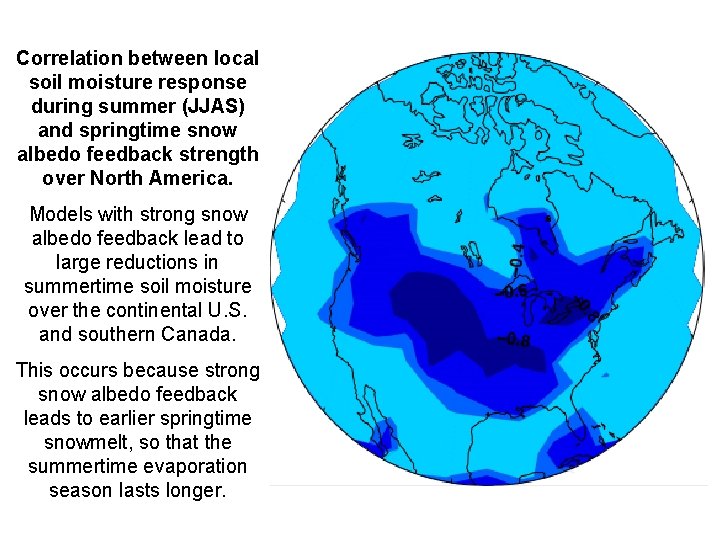

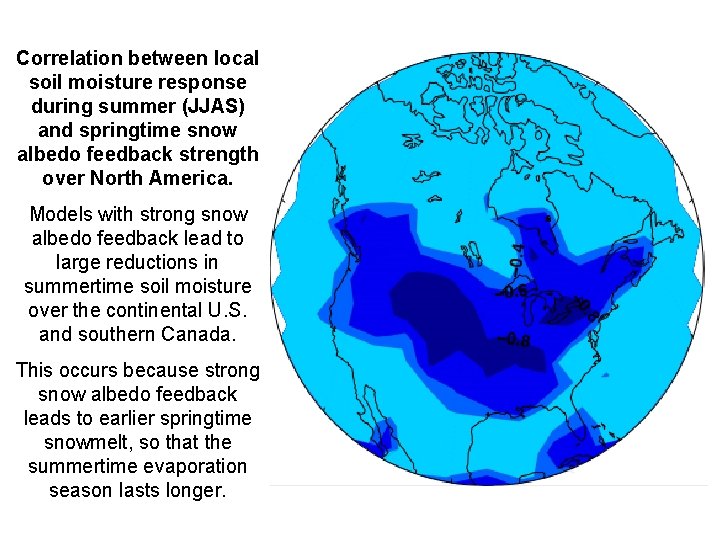

Correlation between local soil moisture response during summer (JJAS) and springtime snow albedo feedback strength over North America. Models with strong snow albedo feedback lead to large reductions in summertime soil moisture over the continental U. S. and southern Canada. This occurs because strong snow albedo feedback leads to earlier springtime snowmelt, so that the summertime evaporation season lasts longer.

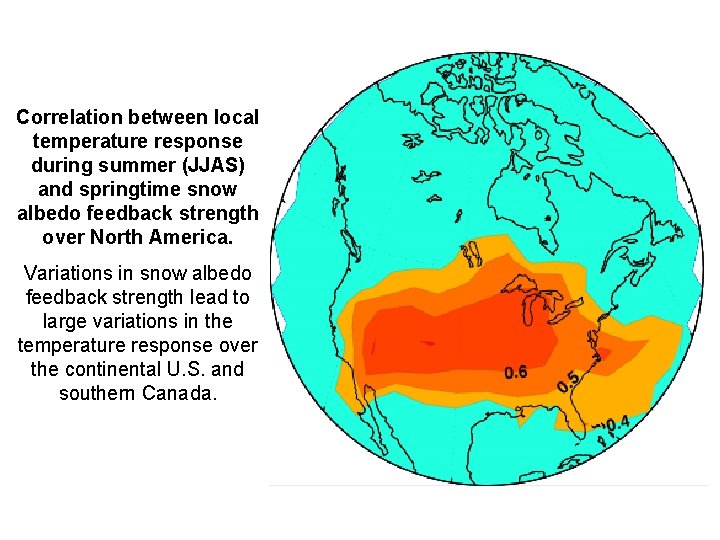

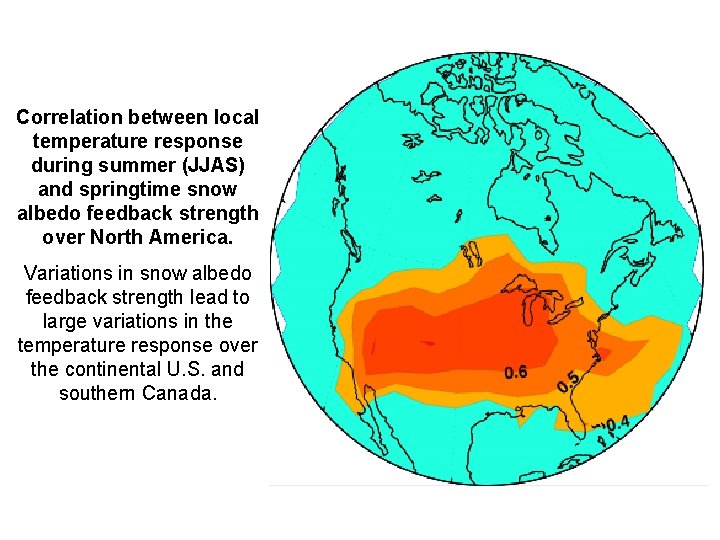

Correlation between local temperature response during summer (JJAS) and springtime snow albedo feedback strength over North America. Variations in snow albedo feedback strength lead to large variations in the temperature response over the continental U. S. and southern Canada.

3 Main Conclusions (1) We can measure the strength of snow albedo feedback accurately in climate change simulations, and there is a roughly three-fold spread in simulations of snow albedo feedback strength. This spread causes much of the spread in the temperature response of current global climate models in northern hemisphere land masses. (2) The feedback’s simulated strength in the seasonal cycle is highly correlated with its strength in climate change. We compared snow albedo feedback's strength in the real seasonal cycle to simulated values. They mostly fall well outside the range of the observed estimate, suggesting many models have an unrealistic snow albedo feedback. The range in the feedback strength can be attributed mostly to differing estimates of the albedo of 100% snow-covered surfaces. (3) These results map out a clear strategy for targeted climate system observation and further model analysis to reduce spread in snow albedo feedback. If we could eliminate the spread in this feedback, it would constrain many critical aspects of future climate change, including the summertime soil moisture reduction in northern hemisphere land masses.

3 Main Conclusions (1) We can measure the strength of snow albedo feedback accurately in climate change simulations, and there is a roughly three-fold spread in simulations of snow albedo feedback strength. This spread causes much of the spread in the temperature response of current global climate models in northern hemisphere land masses. (2) The feedback’s simulated strength in the seasonal cycle is highly correlated with its strength in climate change. We compared snow albedo feedback's strength in the real seasonal cycle to simulated values. They mostly fall well outside the range of the observed estimate, suggesting many models have an unrealistic snow albedo feedback. The range in the feedback strength can be attributed mostly to differing estimates of the albedo of 100% snow-covered surfaces. (3) These results map out a clear strategy for targeted climate system observation and further model analysis to reduce spread in snow albedo feedback. If we could eliminate the spread in this feedback, it would constrain many critical aspects of future climate change, including the summertime soil moisture reduction in northern hemisphere land masses.

3 Main Conclusions (1) We can measure the strength of snow albedo feedback accurately in climate change simulations, and there is a roughly three-fold spread in simulations of snow albedo feedback strength. This spread causes much of the spread in the temperature response of current global climate models in northern hemisphere land masses. (2) The feedback’s simulated strength in the seasonal cycle is highly correlated with its strength in climate change. We compared snow albedo feedback's strength in the real seasonal cycle to simulated values. They mostly fall well outside the range of the observed estimate, suggesting many models have an unrealistic snow albedo feedback. The range in the feedback strength can be attributed mostly to differing estimates of the albedo of 100% snow-covered surfaces. (3) These results map out a clear strategy for targeted climate system observation and further model analysis to reduce spread in snow albedo feedback. If we could eliminate the spread in this feedback, it would constrain many critical aspects of future climate change, including the summertime soil moisture reduction in northern hemisphere land masses.

3 Main Conclusions (1) We can measure the strength of snow albedo feedback accurately in climate change simulations, and there is a roughly three-fold spread in simulations of snow albedo feedback strength. This spread causes much of the spread in the temperature response of current global climate models in northern hemisphere land masses. (2) The feedback’s simulated strength in the seasonal cycle is highly correlated with its strength in climate change. We compared snow albedo feedback's strength in the real seasonal cycle to simulated values. They mostly fall well outside the range of the observed estimate, suggesting many models have an unrealistic snow albedo feedback. The range in the feedback strength can be attributed mostly to differing estimates of the albedo of 100% snow-covered surfaces. (3) These results map out a clear strategy for targeted climate system observation and further model analysis to reduce spread in snow albedo feedback. If we could eliminate the spread in this feedback, it would constrain many critical aspects of future climate change, including the summertime soil moisture reduction in northern hemisphere land masses.