How language learners keep from overgeneralizing Benjamin Bergen

[ How language learners keep from over-generalizing Benjamin Bergen Department of Linguistics University of Hawai`i, Manoa ]

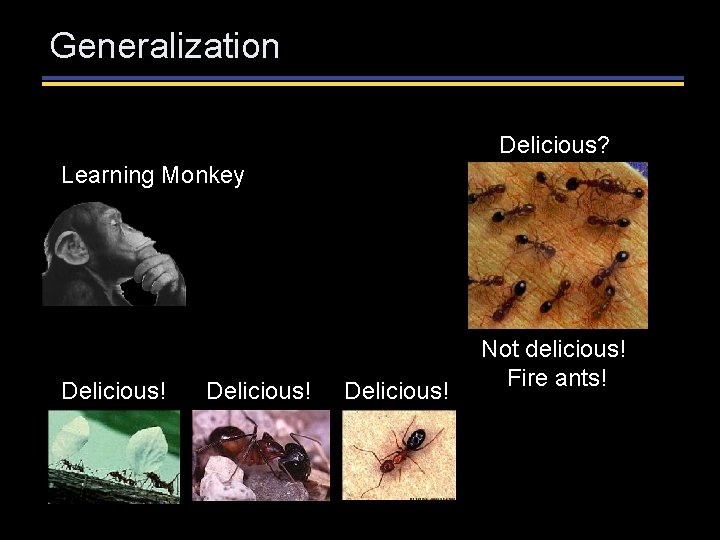

Generalization Delicious? Learning Monkey Delicious! Not delicious! Fire ants!

Generalization All Animals that interact intelligently with their environment generalize. • They have general schemas (or rules, or patterns of action). General: they apply not only to specific tokens, but to whole classes of experiences • These classes are often based on shared perceptual or functional properties • Given new tokens, they can include them in existing categories, depending on perceptual and functional similarity • They then extend expectations about the class to the new members

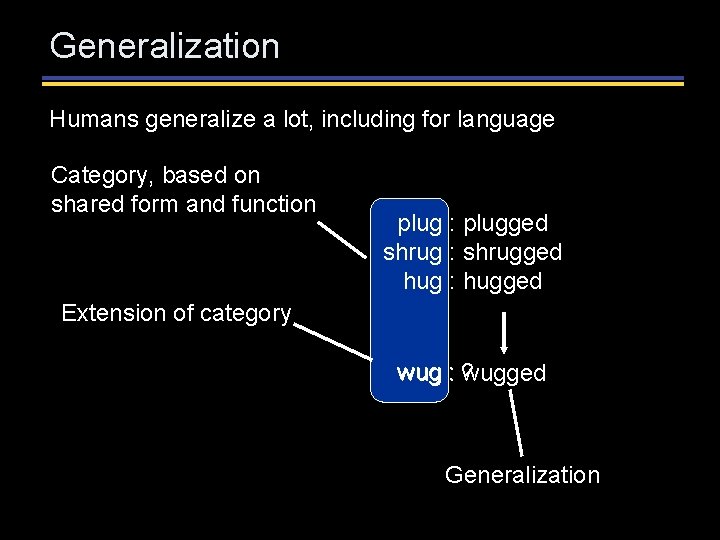

Generalization Humans generalize a lot, including for language Category, based on shared form and function plug : plugged shrug : shrugged hug : hugged Extension of category wug : ? wugged Generalization

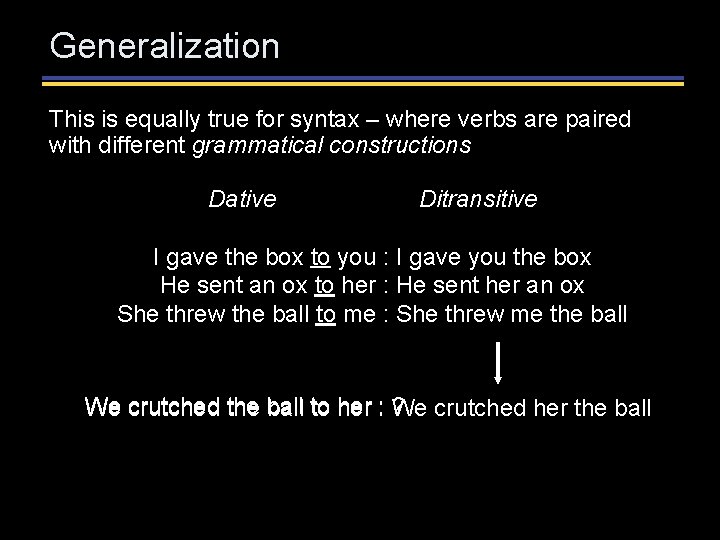

Generalization This is equally true for syntax – where verbs are paired with different grammatical constructions Dative Ditransitive I gave the box to you : I gave you the box He sent an ox to her : He sent her an ox She threw the ball to me : She threw me the ball We crutched the ball to her : ? We crutched her the ball

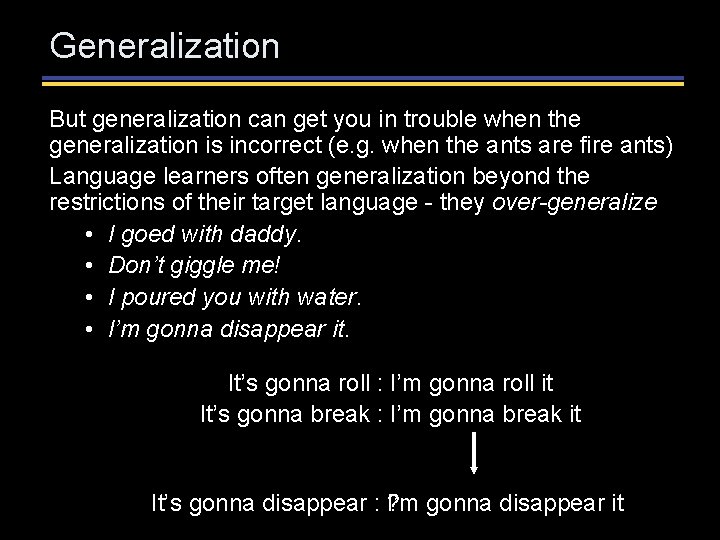

Generalization But generalization can get you in trouble when the generalization is incorrect (e. g. when the ants are fire ants) Language learners often generalization beyond the restrictions of their target language - they over-generalize • I goed with daddy. • Don’t giggle me! • I poured you with water. • I’m gonna disappear it. It’s gonna roll : I’m gonna roll it It’s gonna break : I’m gonna break it It’s gonna disappear : ? I’m gonna disappear it

Generalization But learners, can avoid or retreat from incorrect overgeneralizations • Learning monkey learns to avoid fire ants • A language learner learns that the past tense of go isn’t goed, or that disappear isn’t transitive How do language learners keep from over-generalizing?

Learning mechanisms Proposed mechanisms • Feedback • Innate, language specific expectations • Phonological or semantic cues • Pre-emption • Entrenchment • Distributional comparison

Feedback Direct negative feedback explicitly identifies an error in the child’s speech and them provides a correction Child: I goed with Daddy. Parent: No, you went with Daddy. Although occasionally present in child-directed speech, direct negative feedback is sparse, ambiguous, and often ignored (Marcus 1993) And for that matter, when do children ever do what you tell them to?

Feedback Indirect negative feedback doesn’t explicitly identify an error, but does provide a correction Child: I goed with Daddy. Parent: That’s right, you went with Daddy. Child language learners use it, but only for correcting limited sorts of errors: the verb to be and third person -s (Saxton et al. 2005).

Innate expectations The purported evidence for innate, language-specific constraints on grammar is hotly contested Fortunately, we can ignore this controversy Because there’s no reason to believe in an innate specification that contribute can’t be paired with the ditransitive or that go takes an irregular past tense

Semantic classes Syntactic patterns often follow semantic generalizations, so learners might use word meanings to constrain their generalizations (Pinker 1989). How can you learn not to say I’m gonna disappear it? Disappear is like other verbs (vanish, appear, emerge, arrive), that describe an immediate change of presence. All these semantically similar verbs can be used in one grammatical structure: It vanished/emerged/appeared), but not the other: I vanished/emerged/appeared it. But semantics is not the whole story. Donate and contribute aren’t in a difference class than give and send.

Phonological classes Sound patterns have been proposed as partly responsible for limiting generalizations (Pinker 1989) For instance, we know that contribute usually is not acceptable in the ditransitive: • I contributed you the book This is also true of many polysyllabic words, e. g. donate, deliver However, even long novel words can be accommodated by the ditransitive (Wasow 1981), as in: • I satellited him a message

Pre-emption Generalization produces expectations: • goed • John donated the library $10 But learners do not observe these because they are illicit Instead, they observe a different form • went • John donated $10 to the library Pre-emption: the suppression of a possible, predicted form in the face of a functionally equivalent alternative exists. Hearing pre-empting grammatical structures suppresses (over)generalization, starting at about age 5 (Brooks & Tomasello 1999, Brooks & Zizak 2002). Critically, it can work as quickly as the first hearing.

Entrenchment “the more frequently children hear a verb used in a particular construction (the more firmly its usage is entrenched), the less likely they will be to extend that verb to any novel construction with which they have not heard it used. ” (Brooks et al. 1999) Basically, the more you’ve used a word one way, the less adventurous you will be in using it other ways

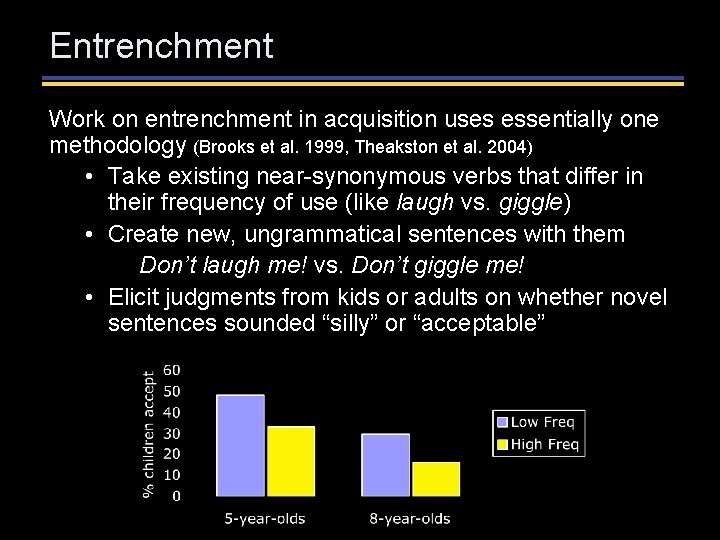

Entrenchment Work on entrenchment in acquisition uses essentially one methodology (Brooks et al. 1999, Theakston et al. 2004) • Take existing near-synonymous verbs that differ in their frequency of use (like laugh vs. giggle) • Create new, ungrammatical sentences with them Don’t laugh me! vs. Don’t giggle me! • Elicit judgments from kids or adults on whether novel sentences sounded “silly” or “acceptable”

Entrenchment A weakness of this approach to entrenchment: it uses existing verbs We don’t know what experience learners have had with them, including any of the types of constraint we’ve seen so far (so this is actually a quasi-experiment) The rest of the talk: an truly experimental approach to how frequency affects overgeneralization, using new verbs.

Pilot Experiment Does higher frequency of a word-construction pairing suppress generalization of the word to other (unobserved) grammatical constructions? Trained adult native speaker of English on new verbs, using only one grammatical construction, varying the frequency Then tested how acceptable they thought new sentences were that used the same construction or a different construction

Method: Training Present participants with new words in two grammatical patterns. • New words are novel, denominal verbs (verbs from nouns) spatula, crutch, ice-pick, tow-truck • In one of two grammatical structures: dative or ditransitive Ralph crutched the nurse the clipboard. (ditransitive) Ralph crutched the clipboard to the nurse. (dative) She spatulaed Tommy some cookie dough. (ditransitive) She spatualed some cookie dough to Tommy. (dative) • Instructions: learn a new dialect of English as best they can and then demonstrate what they've learned through acceptability judgments about new sentences in the dialect.

Method: Training Eight novel verbs - none conventionally used with either dative or ditransitive • (to) branch, broom, bulldozer, crutch, motorcycle, spatula, tennis-racket, and towtruck • Each occurs for a given participant with only one structure: dative or ditransitive • Each occurs for a given participant with High (8 times) or Low (3 times) frequency Eight sentence pairs for each verb (eight dative and eight ditransitive - otherwise identical) • All denoted physical transfer of an object to a recipient using a means specified by the verb

Method: Training In each trial: first a context sentence, which gives them some background • The nurse was clearly looking for her clipboard. Then a training sentence using a novel verb in dative or distransitive Ralph crutched the nurse the clipboard. (ditransitive) Ralph crutched the clipboard to the nurse. (dative) After 1/3 of the target sentences, they type the sentence exactly as they saw it. Each of eight verbs is assigned to High or Low frequency and to Dative or Ditransitive training construction. Latin-squaring produces four lists; each participant is randomly assigned to one.

Method: Testing Test sentences • Same verbs as in the training • Different subjects and objects than in the training sentences. An acceptability judgment task on each of the new verbs. • Each verb presented once with each construction in random order Participants indicate whether the new sentences are grammatical in the new dialect on a scale: – 3 (very bad) to +3 (very good).

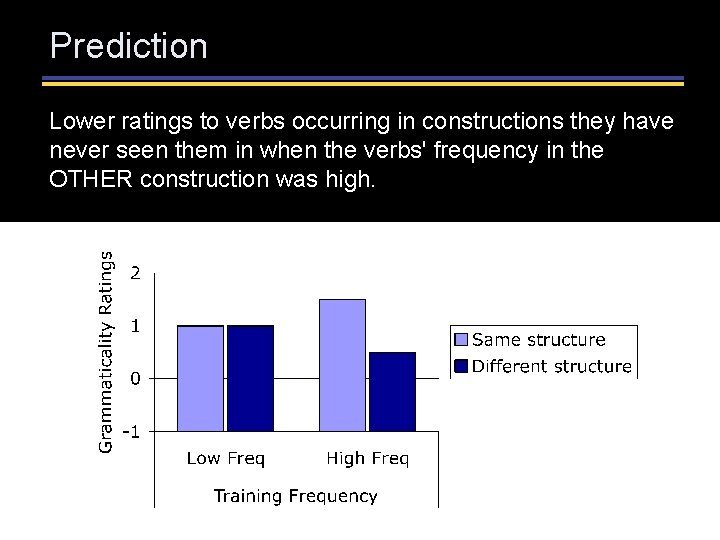

Prediction Lower ratings to verbs occurring in constructions they have never seen them in when the verbs' frequency in the OTHER construction was high.

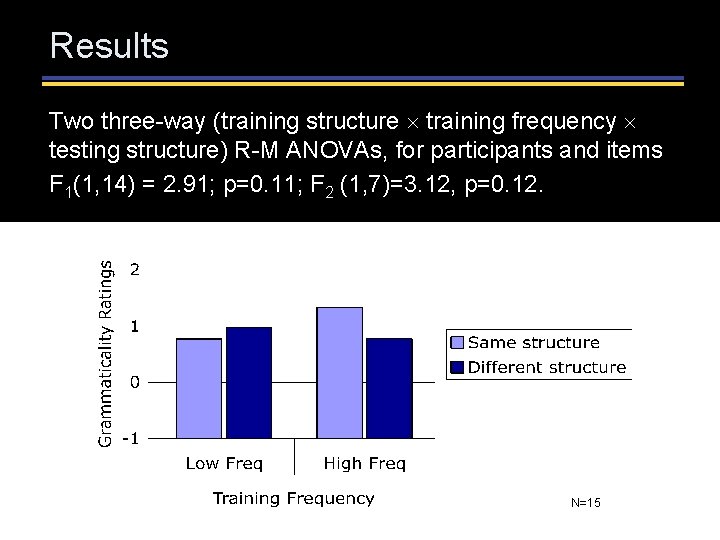

Results Two three-way (training structure training frequency testing structure) R-M ANOVAs, for participants and items F 1(1, 14) = 2. 91; p=0. 11; F 2 (1, 7)=3. 12, p=0. 12. N=15

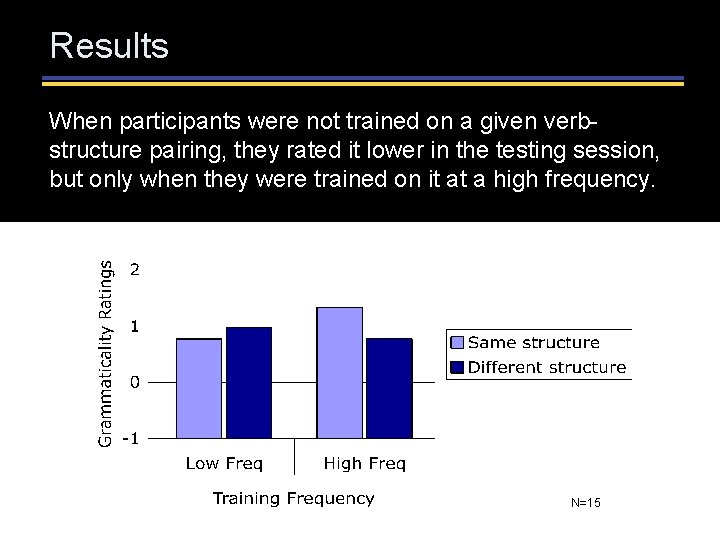

Results When participants were not trained on a given verbstructure pairing, they rated it lower in the testing session, but only when they were trained on it at a high frequency. N=15

Main Experiment Pilot study results approach significance with very small N Spoken stimuli are critical to explain learning by young children Main experiment identical to pilot, save minor changes accommodating the auditory modality Sentences (from pilot) were recorded by a male, native speaker of English using normal sentence prosody. Hypothesis: Lower acceptability ratings for unheard verb-construction pairings, but only at high frequency of presentation N=15

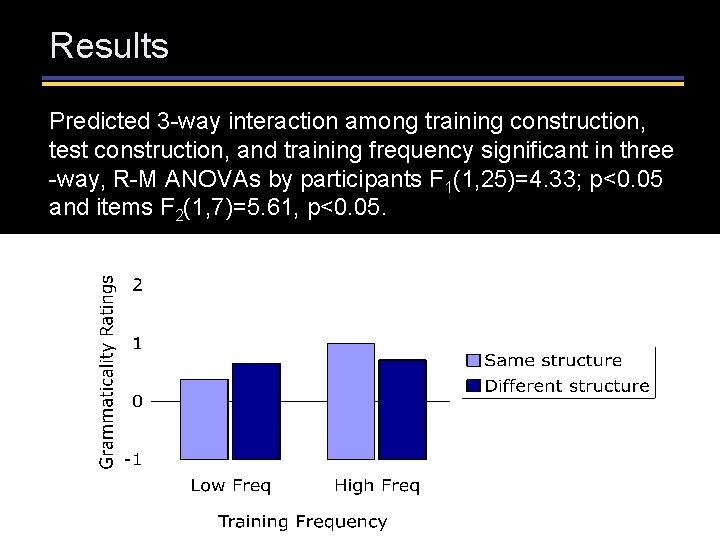

Results Predicted 3 -way interaction among training construction, test construction, and training frequency significant in three -way, R-M ANOVAs by participants F 1(1, 25)=4. 33; p<0. 05 and items F 2(1, 7)=5. 61, p<0. 05. These findings replicated the results of Exp. 1, but with more participants showed statistical significance for the predicted three-way interaction. N=15

Results It seems like entrenchment could be real But these results are also compatible with a different explanation, distributional comparison.

Results In distributional comparison, the learner computes the likelihood that, given the overall frequency of two construction, they will observe the same construction with a given word n times in a row. If the probability is low enough, this implies not only that the verb hasn’t occurred with this construction, but WON’T occur with the construction.

Summary Generalization is a learning process that we see throughout human and other animal cognition As applied to language, the key to knowing what generalization can explain is to know how learners keep from generalizing In part, they use feedback from others, in part phonological and semantic cues, and as we’ve seen here, frequency is a useful tool as well Future work will disentangle exactly how learners use frequency

Thanks Jawee Perla (LCL) Iris Kolberg (LCL) Kamil ud Deen (UH) Stephan Gries (UCSB) Anatol Stefanowitsch (Bremen) Mark Paskin (Google) Tom Griffiths (UC Berkeley)

- Slides: 31