How Bitcoin Achieves Decentralization Centralization vs Decentralization Scrooge

How Bitcoin Achieves Decentralization

Centralization vs. Decentralization Scrooge. Coin achieves a lot of what we want in a ledger‐based cryptocurrency, but it has one glaring problem — it relies upon the centralized authority called Scrooge. The mechanism through which Bitcoin achieves decentralization is not purely technical, but it’s a combination of ütechnical methods and üclever incentive engineering

Competing paradigms that underlie many digital technologies. Centralization vs. Decentralization Internet: a famously decentralized system that has historically competed with and prevailed against alternatives like AOL’s and Compu. Serve’s. Email: a decentralized system based on the Simple Mail Transfer Protocol (SMTP), an open standard. Social networking: a centralized model, systems like Facebook and Linked. In dominate this space.

Decentralization is not all-or-nothing Almost no system is purely decentralized or purely centralized. Email: decentralized protocol, but dominated by centralized webmail services. Bitcoin: decentralized protocol, but services like Bitcoin exchanges and wallet software may be centralized or decentralized to varying degrees.

Aspects of decentralization in Bitcoin 1. Who maintains the ledger of transactions? 2. Who has authority over which transactions are valid? 3. Who creates new bitcoins? 4. Who determines how the rules of the system change? 5. How do bitcoins acquire exchange value? Beyond the protocol: Exchanges, wallet software, service providers…

Aspects of decentralization in Bitcoin • Peer‐to‐peer network: close to purely decentralized. Anybody can run a Bitcoin node, low barrier to entry. • Bitcoin mining: technically also open to anyone, but it requires a very high capital cost • Updates to the software: most nodes run the reference implementation, and core developers are trusted by the community and have a lot of power.

Bitcoin’s key challenge Key technical challenge of decentralized e‐cash: distributed consensus How to decentralize Scrooge. Coin

Why consensus protocols? Traditional motivation: reliability in distributed systems Distributed key‐value store enables various applications: • DNS • Public key directory • Stock trades • …. Altcoins

Distributed consensus protocol There are n nodes that each has an input value. Some of these nodes are faulty or malicious. A distributed consensus protocol has the following two properties: • It must terminate with all honest nodes in agreement on the value • The value must have been generated by an honest node

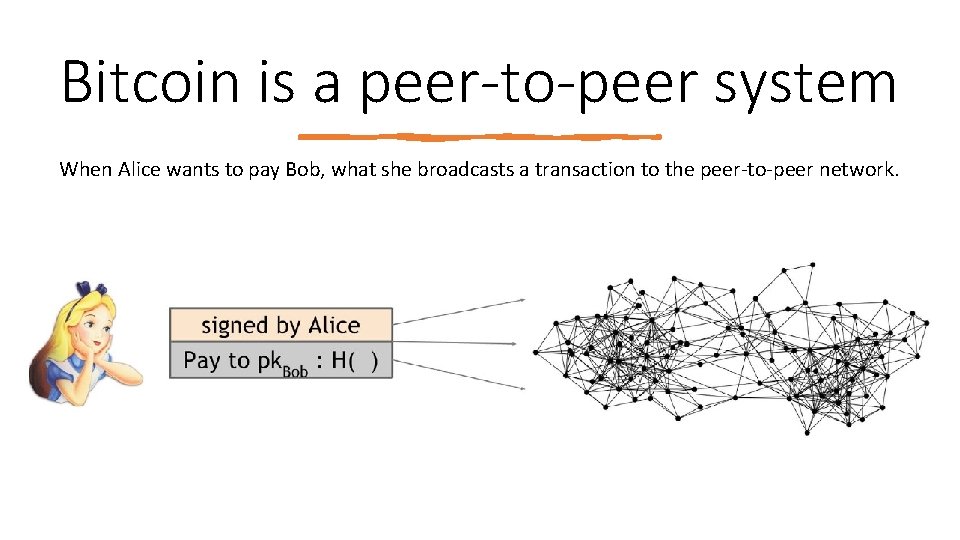

Bitcoin is a peer-to-peer system When Alice wants to pay Bob, what she broadcasts a transaction to the peer‐to‐peer network.

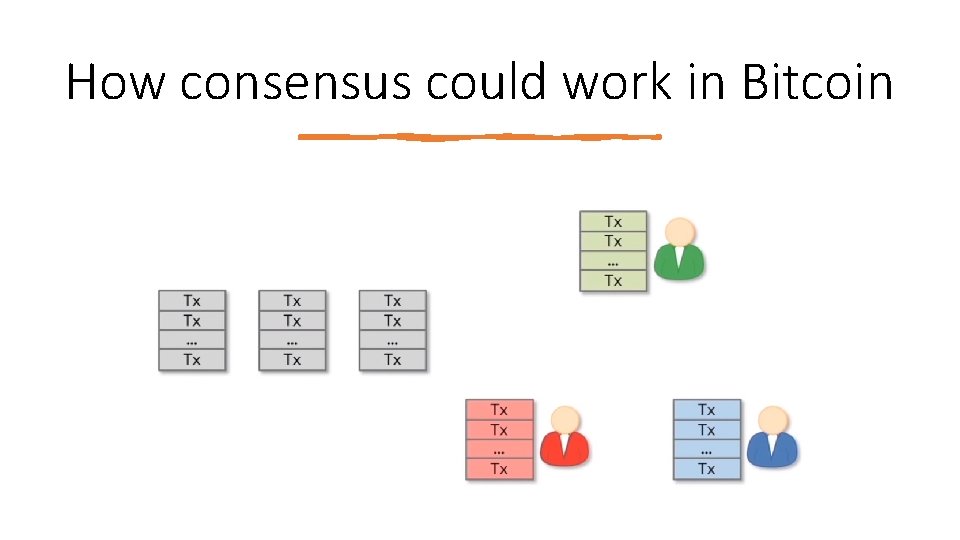

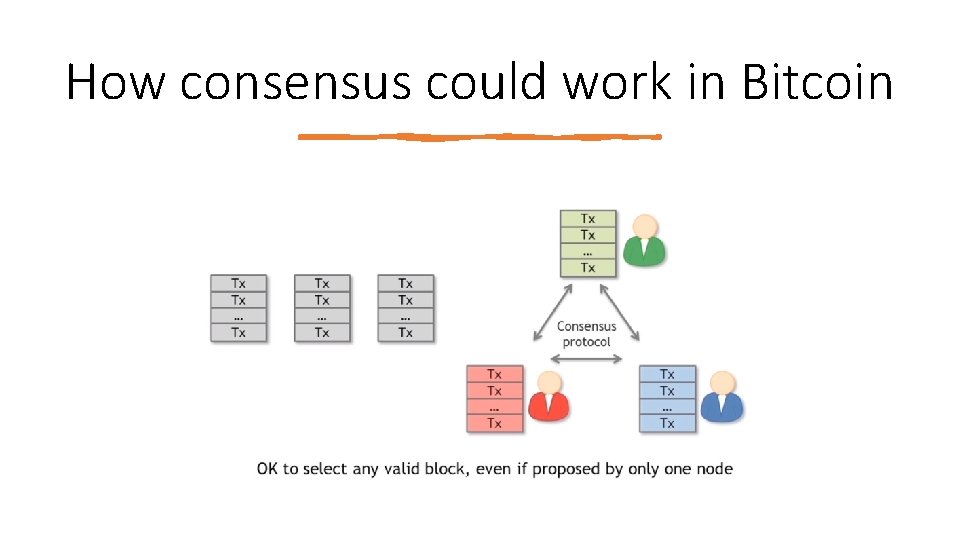

How consensus could work in Bitcoin Given that a variety of users are broadcasting these transactions to the network, the nodes must agree on exactly which transactions were broadcast and the order in which these transactions happened. At any given time: • All the nodes have a sequence of blocks, each containing a list of transactions, that they’ve reached consensus on. • Each node has a pool of outstanding transactions that it has heard about.

How consensus could work in Bitcoin

How consensus could work in Bitcoin

How consensus could work in Bitcoin

How consensus could work in Bitcoin

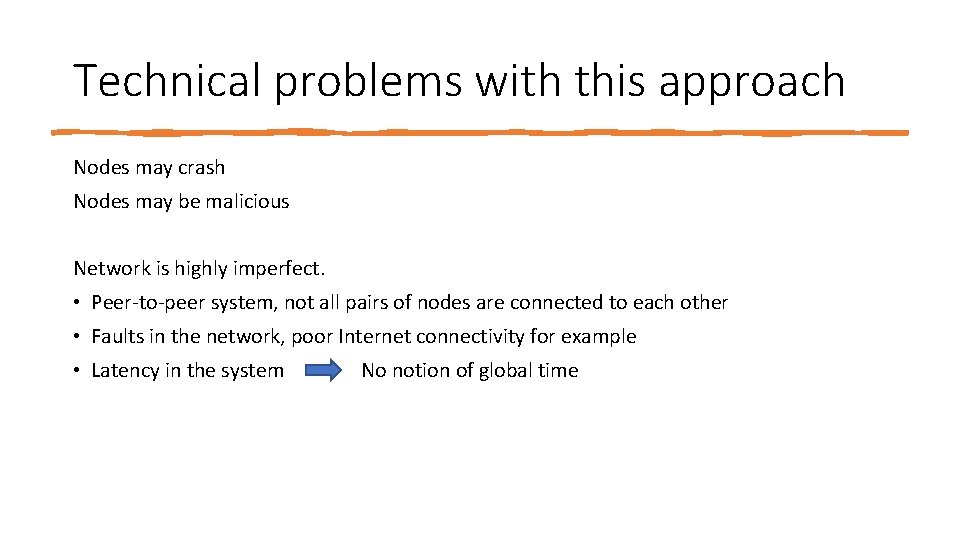

Technical problems with this approach Nodes may crash Nodes may be malicious Network is highly imperfect. • Peer‐to‐peer system, not all pairs of nodes are connected to each other • Faults in the network, poor Internet connectivity for example • Latency in the system No notion of global time

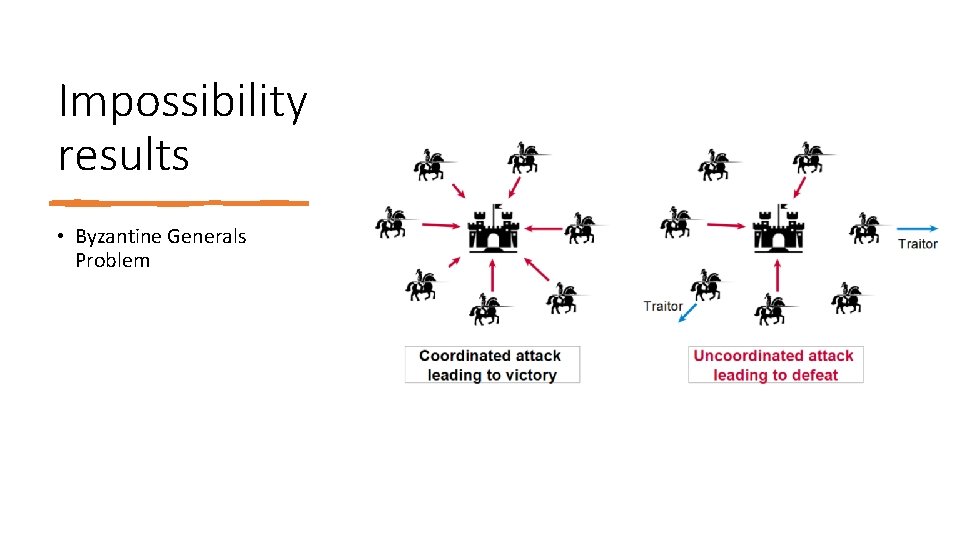

Impossibility results • Byzantine Generals Problem

Impossibility results Fischer‐Lynch‐Paterson impossibility result: • nodes acting in a deterministic manner, • consensus is impossible with even a single faulty process.

Some wellknown protocols Paxos: • Never produces inconsistent result • Can rarely get stuck

These results say more about the model than about the problem Breaking traditional assumptions The models were developed to study systems like distributed databases. Bitcoin violates many of the assumptions built into the models

Bitcoin consensus • Bitcoin consensus works better in practice than in theory. • We observe consensus working, but have not developed theory to fully explain why it works. • Theory is important as it can help us predict unforeseen attacks and problems

Assumptions Bitcoin violates Introduces incentives for acting honestly • This is only possible in Bitcoin because it is a currency Embraces randomness • it does away with the notion of a specific starting point and ending point for consensus • consensus happens over a long period of time, about an hour

Node IDs, where are they useful? Some protocols need node IDs Assume less than 50% malicious

Bitcoin nodes don’t have IDs • Identity is hard in a P 2 P system • Sybil attack: Sybils are copies of nodes that a malicious adversary can create to look like there a lot of different participants • Pseudonymity is a goal of Bitcoin

Weaker assumption: select a random node Analogy: lottery or raffle When tracking and verifying identities is hard, we give people tokens, tickets, etc. Now we can pick a random ID and select that node.

Implicit Consensus In each round, a random node is picked This node proposes the next block in the chain Other nodes implicitly accept or reject this block: • by extending it, • or by ignoring it. Every block contains hash of the block it extends.

Bitcoin consensus algorithm (simplified) • New transactions are broadcast to all nodes • Each node collects new transactions into a block • In each round a random node gets to broadcast its block • Other nodes accept the block only if all transactions in it are valid (unspent, valid signatures) • Nodes express their acceptance of the block by including its hash in the next block they create

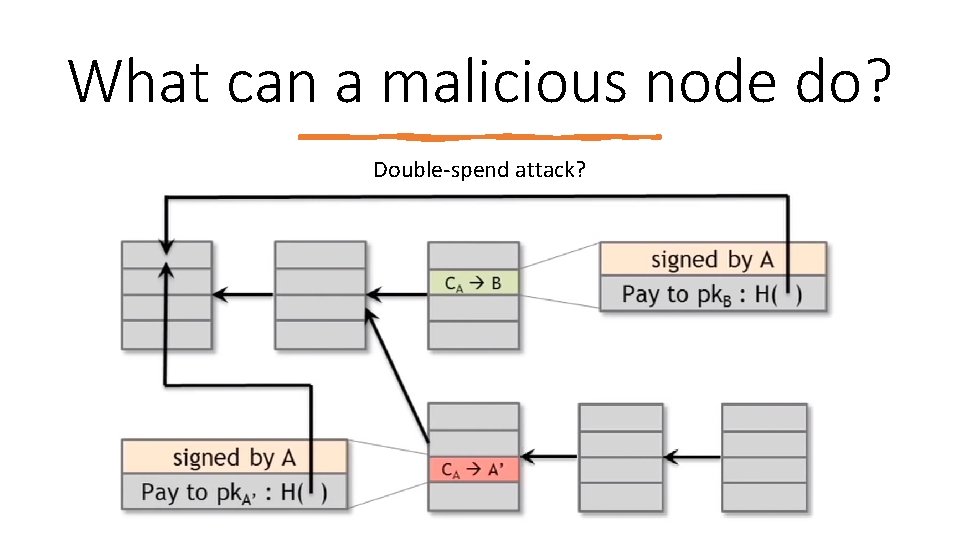

What can a malicious node do? • Stealing Bitcoins? • Denial of service attack? • Double‐spend attack?

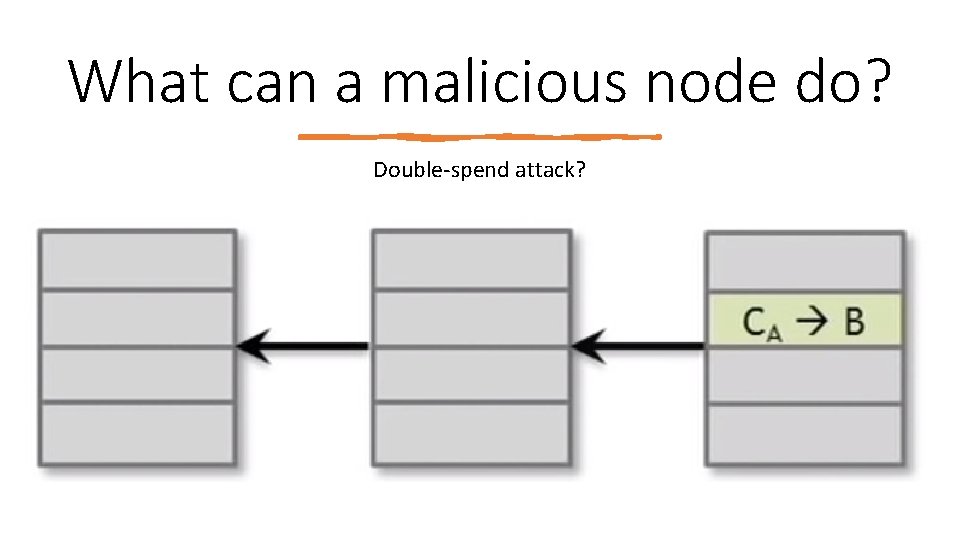

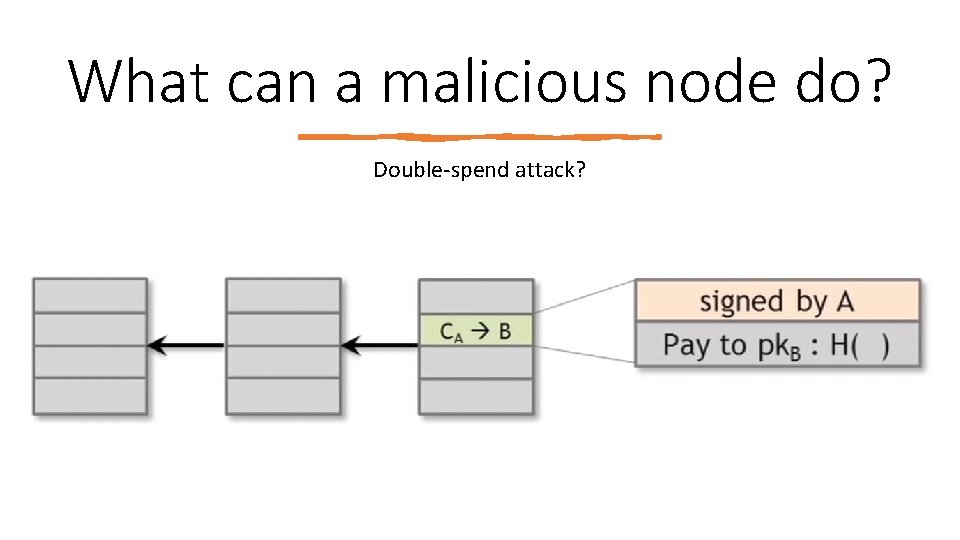

What can a malicious node do? Double‐spend attack?

What can a malicious node do? Double‐spend attack?

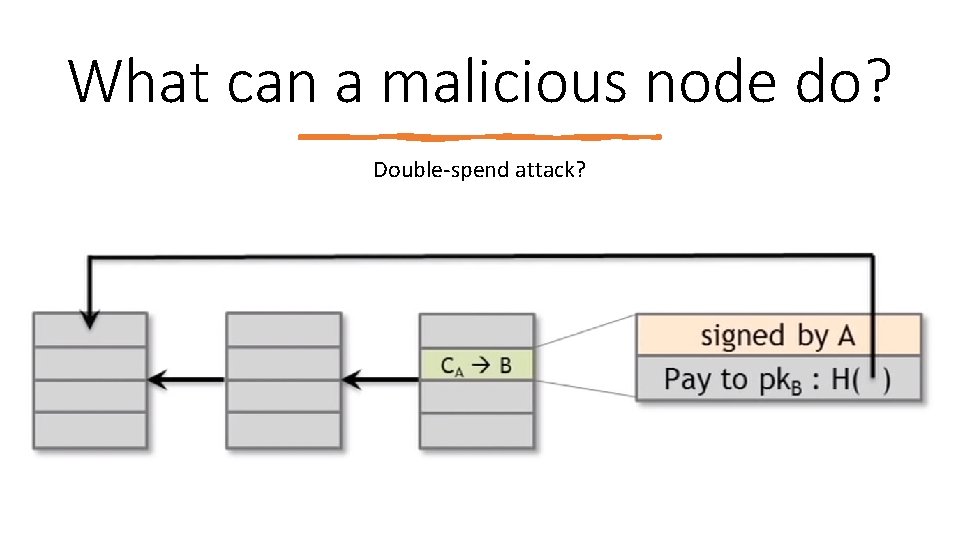

What can a malicious node do? Double‐spend attack?

What can a malicious node do? Double‐spend attack?

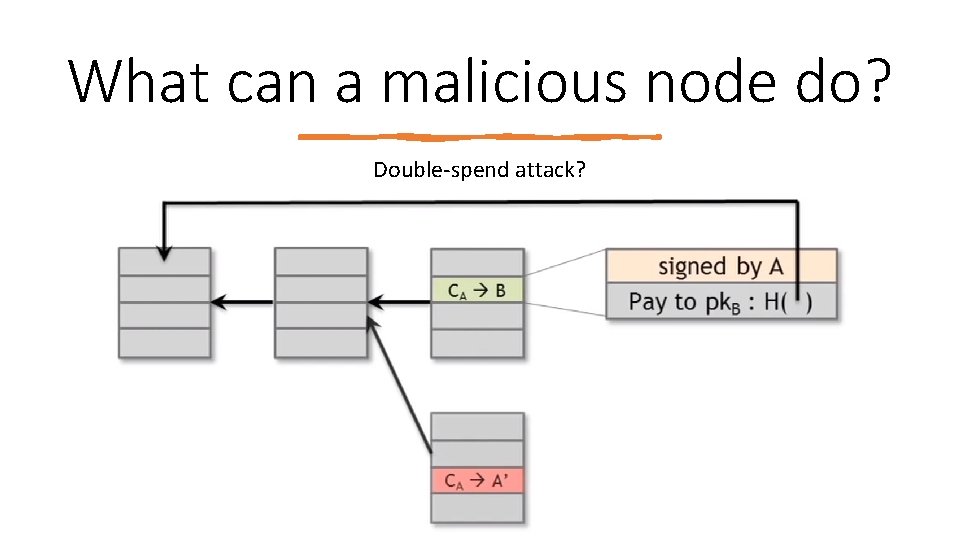

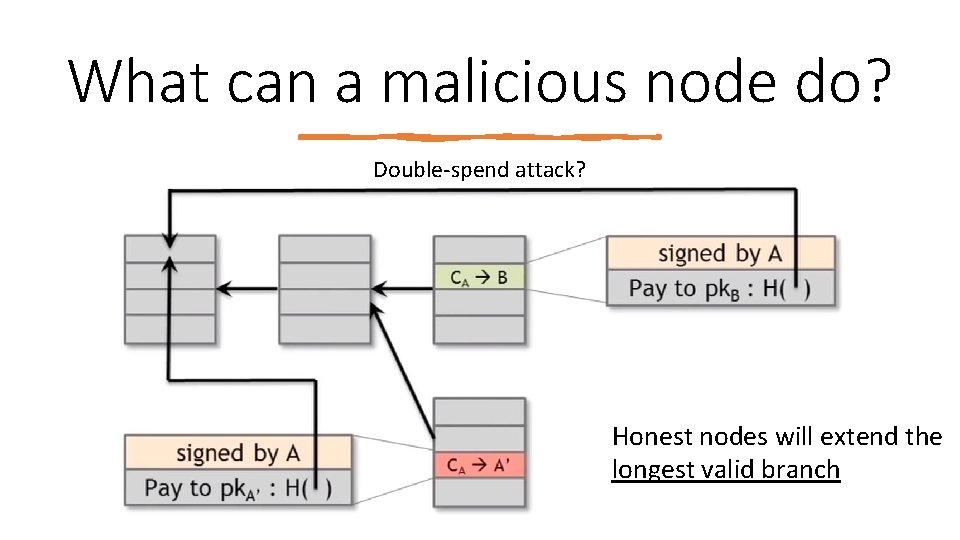

What can a malicious node do? Double‐spend attack? Honest nodes will extend the longest valid branch

What can a malicious node do? Double‐spend attack?

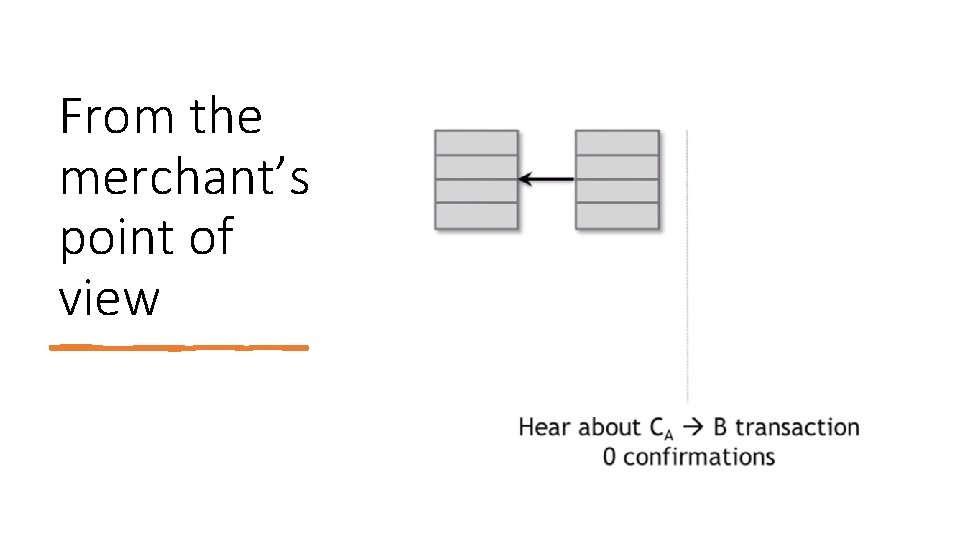

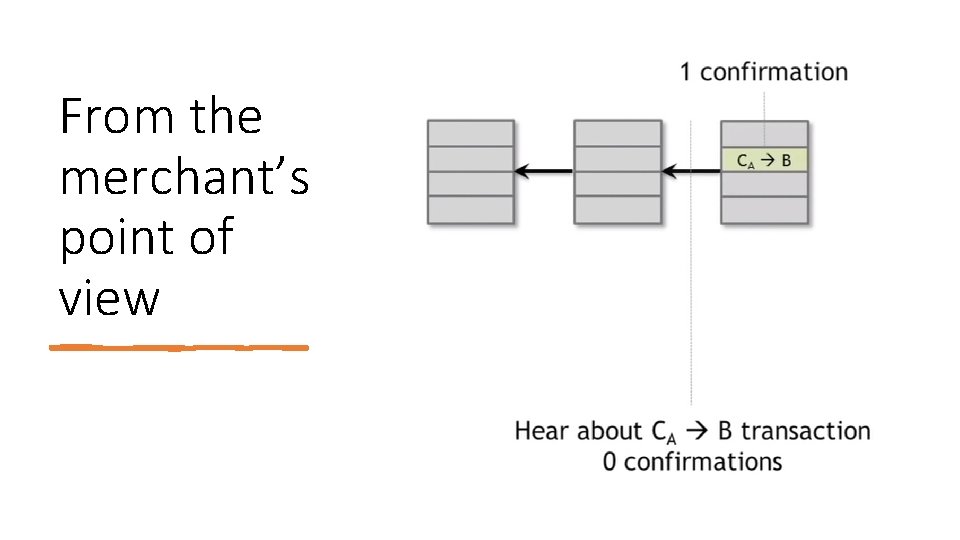

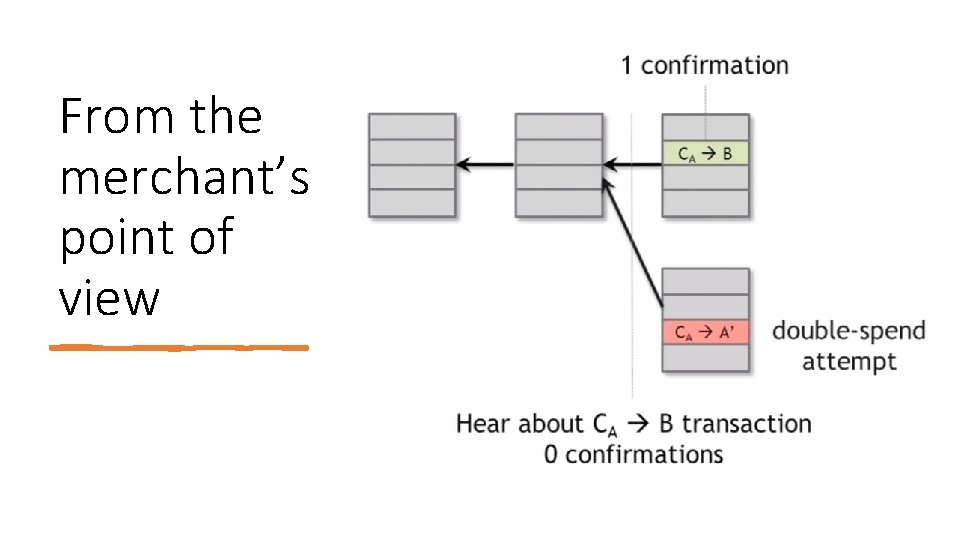

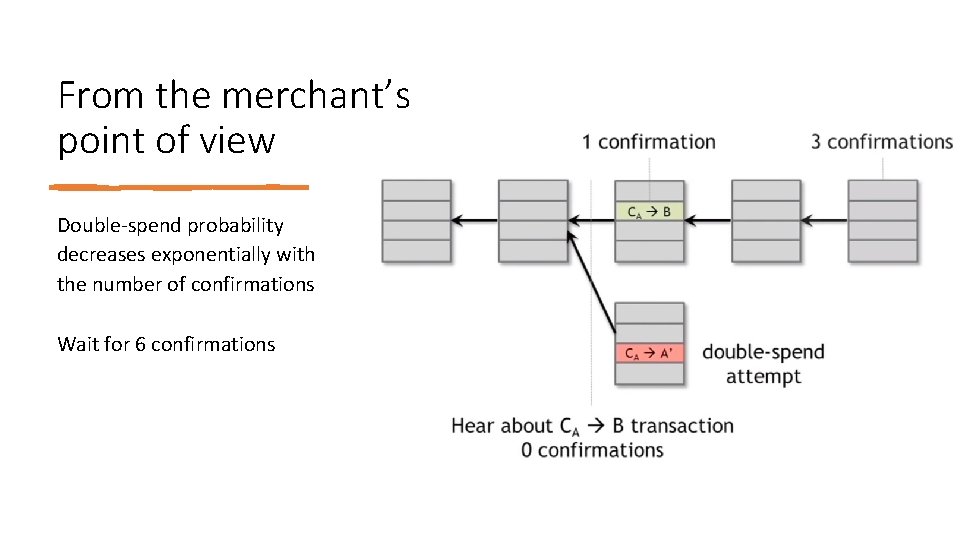

From the merchant’s point of view

From the merchant’s point of view

From the merchant’s point of view

From the merchant’s point of view Double‐spend probability decreases exponentially with the number of confirmations Wait for 6 confirmations

Recap Protection against invalid transactions is entirely cryptographic, but it is enforced by consensus. Protection against double‐spending is purely by consensus. • Cryptography has nothing to say about this, and two transactions that represent a double‐spend attempt are both valid from a cryptographic perspective. You’re never 100% sure that a transaction is on the consensus branch. Guarantee is probabilistic.

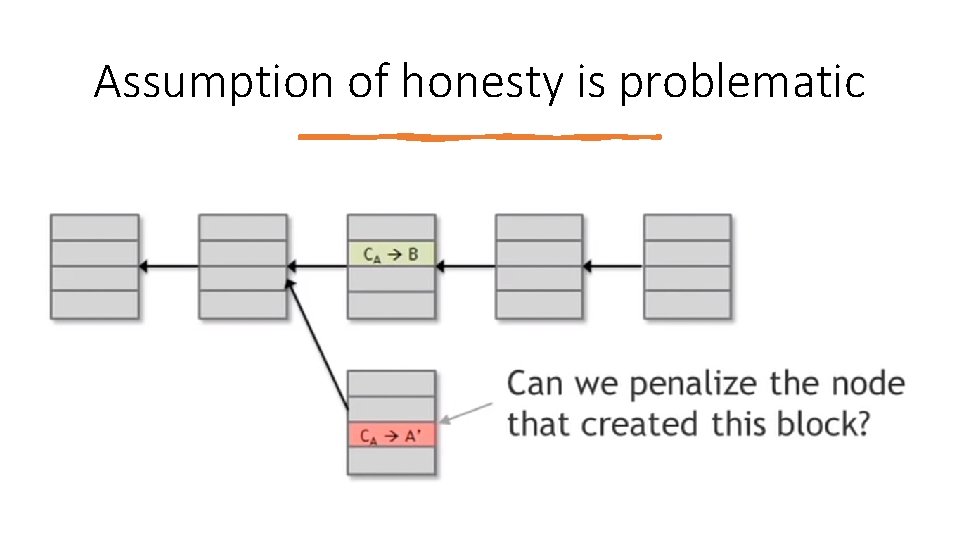

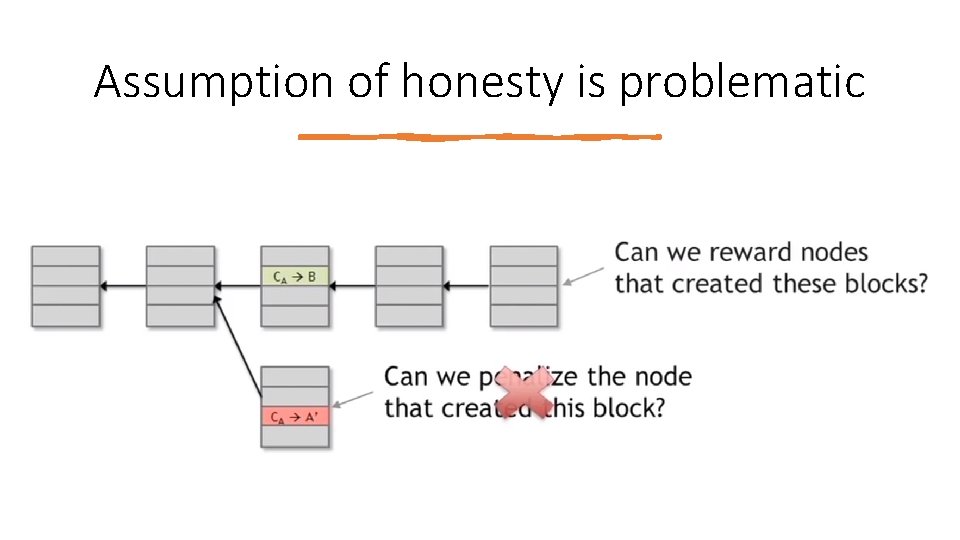

Assumption of honesty is problematic We assumed that: • we’re able to pick a random node and, • at least 50 percent of the time, this process will pick an honest node. Can we give nodes an incentive for behaving honestly?

Assumption of honesty is problematic

Assumption of honesty is problematic

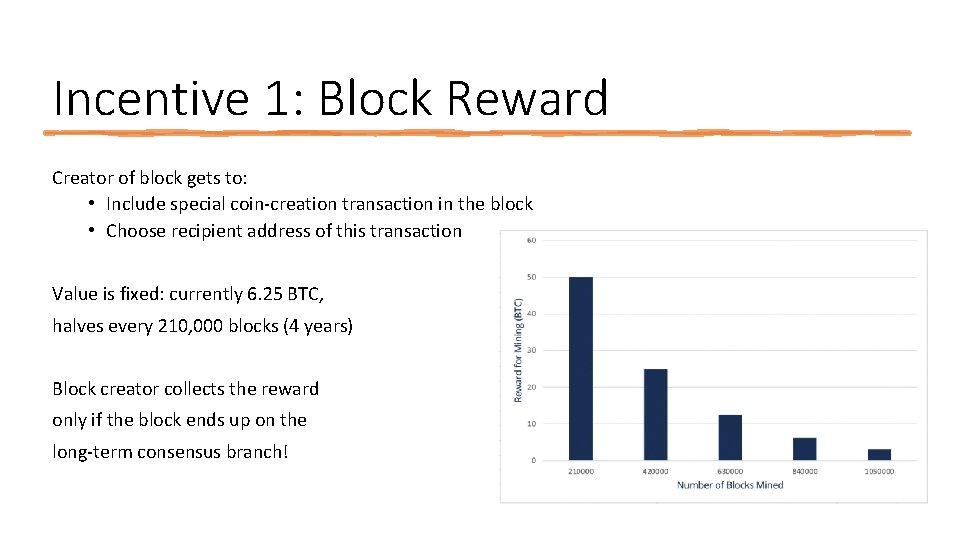

Incentive 1: Block Reward Creator of block gets to: • Include special coin‐creation transaction in the block • Choose recipient address of this transaction Value is fixed: currently 6. 25 BTC, halves every 210, 000 blocks (4 years) Block creator collects the reward only if the block ends up on the long‐term consensus branch!

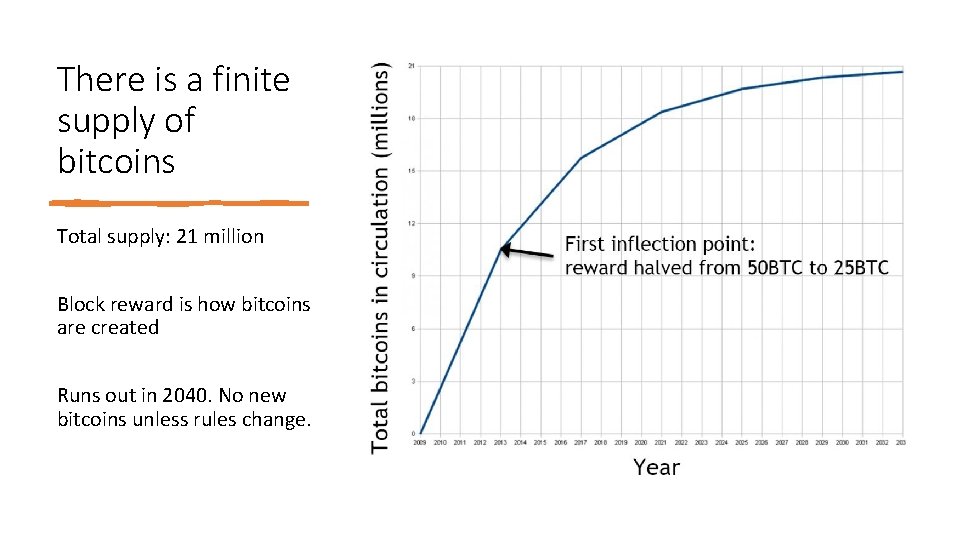

There is a finite supply of bitcoins Total supply: 21 million Block reward is how bitcoins are created Runs out in 2040. No new bitcoins unless rules change.

Incentive 2: transaction fees • The creator of any transaction can choose to make the total value of the transaction outputs less than the total value of its inputs. • Whoever creates the block that first puts that transaction into the block chain gets to collect the difference, which acts as a transaction fee. • The transaction fee is purely voluntary, but we expect that it will become more and more important. How the system will evolve depends on a lot of game theory which hasn’t been fully worked out yet.

Remaining problems 1. How to pick a random node? 2. How to avoid a free‐for‐all due to rewards? 3. How to prevent Sybil attacks?

Proof of work To approximate selecting a random node: select nodes in proportion to a resource that no one can monopolize. • In proportion to computing power: proof‐of‐work • In proportion to ownership: proof‐of‐stake

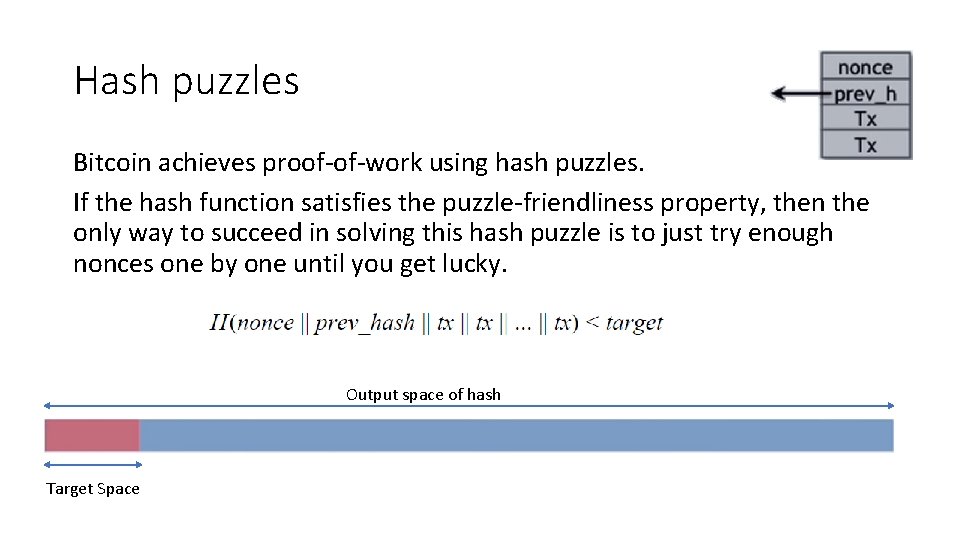

Hash puzzles Bitcoin achieves proof‐of‐work using hash puzzles. If the hash function satisfies the puzzle‐friendliness property, then the only way to succeed in solving this hash puzzle is to just try enough nonces one by one until you get lucky. Output space of hash Target Space

Po. W property 1: difficult to compute

Po. W property 2: parameterizable cost Nodes automatically re‐calculate the target every 2016 blocks (two weeks). Goal: average time between blocks: 10 minutes. Probability ( Alice generates the next block ) = fraction of global hash power she controls

Key security assumption Attacks are infeasible if the majority of miner weighted by hash power follow the protocol. In distributed systems and computer security: we assume that some percentage of nodes are honest and show that the system works as intended even if the other nodes behave arbitrarily. In game theory: every node acts according to its incentives. Is the default miner behavior a “Nash equilibrium”?

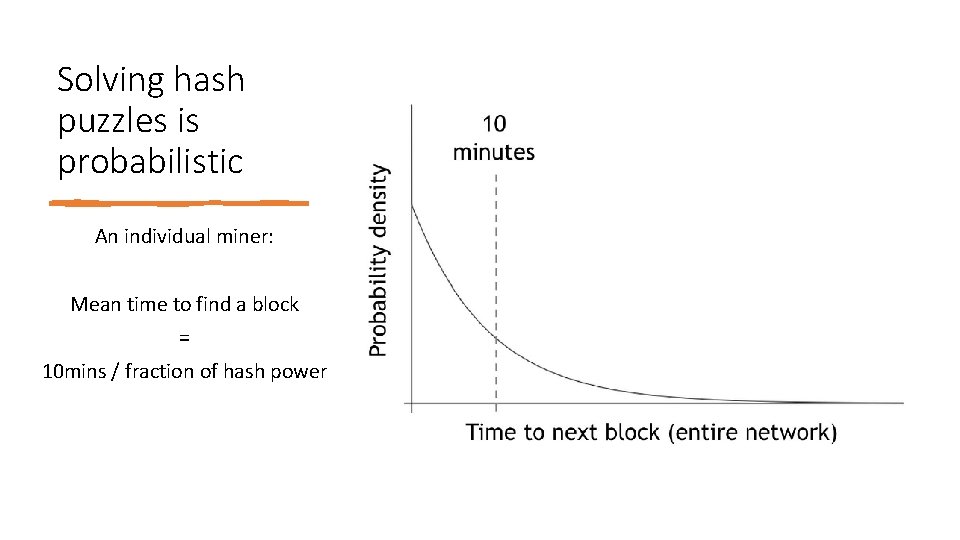

Solving hash puzzles is probabilistic An individual miner: Mean time to find a block = 10 mins / fraction of hash power

Po. W property 3: trivial to verify Nonce is published as part of the block. Other miners simply verify that:

Mining economics If mining reward > mining cost then miner profits where mining reward = block reward + tx fees mining cost = hardware cost + operating costs (electricity, cooling, etc. ) Analyzing whether it makes sense to mine is a complicated game theory problem that’s not easily answered.

Putting it all together Identities, Transactions, P 2 P network, Blockchain & Consensus, Hash puzzles & mining

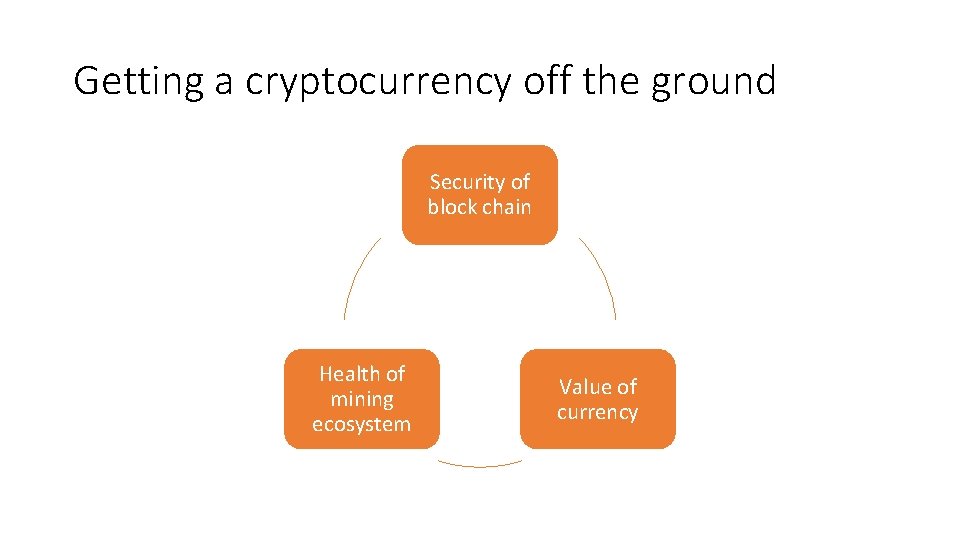

Getting a cryptocurrency off the ground Security of block chain Health of mining ecosystem Value of currency

What can a 51% attacker do? Steal coins from an existing address? 51% attack Suppress some transactions? • From the blockchain • From the P 2 P network Change the block reward? Destroy confidence in Bitcoin?

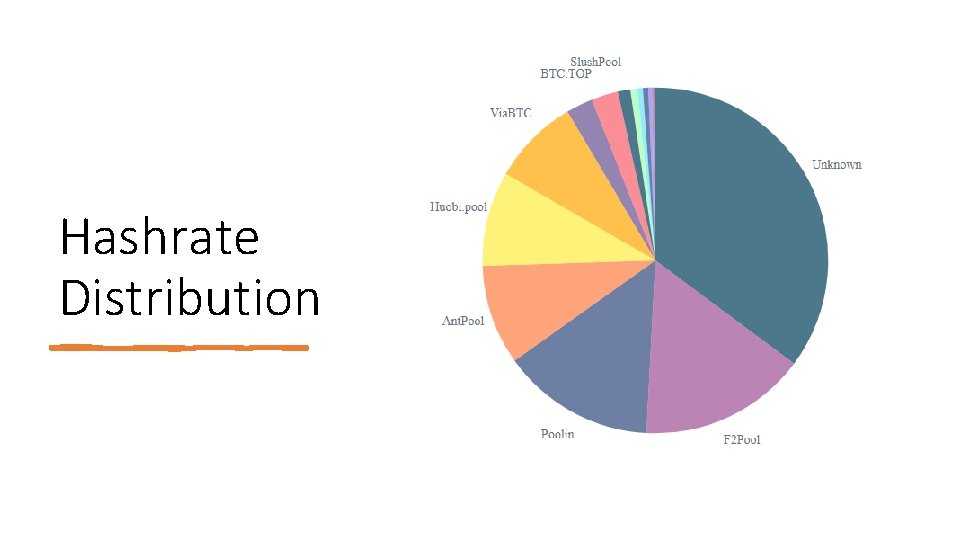

Hashrate Distribution

- Slides: 58