Homestead Act 1862 On January 1 1863 Daniel

- Slides: 12

Homestead Act 1862

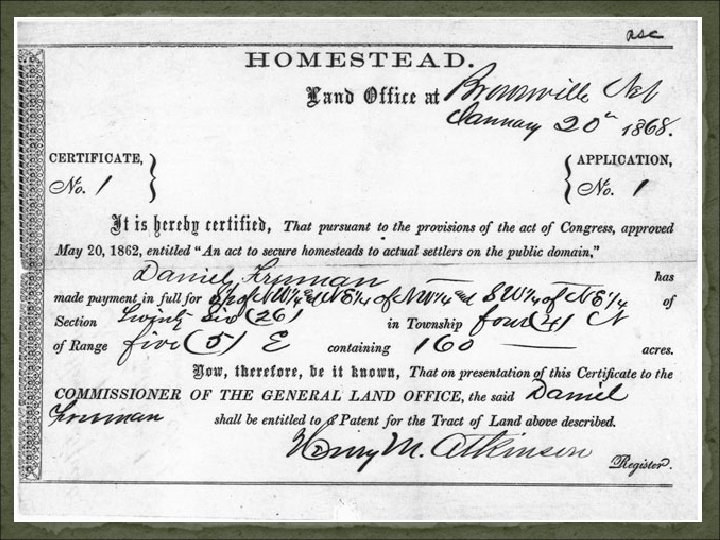

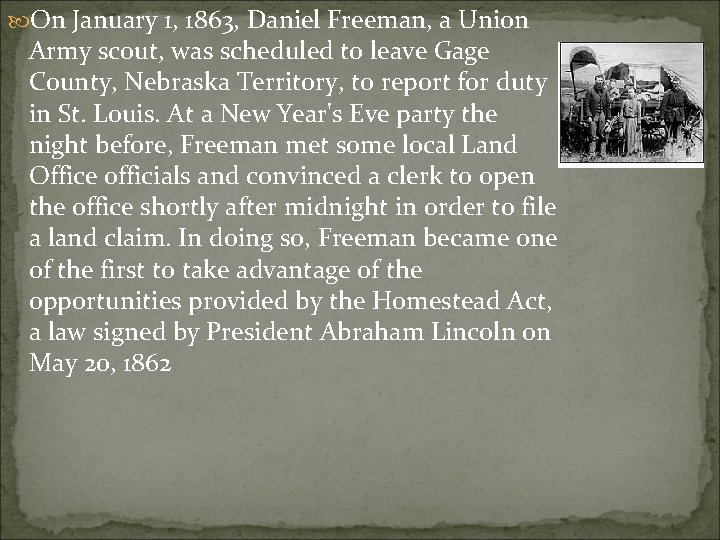

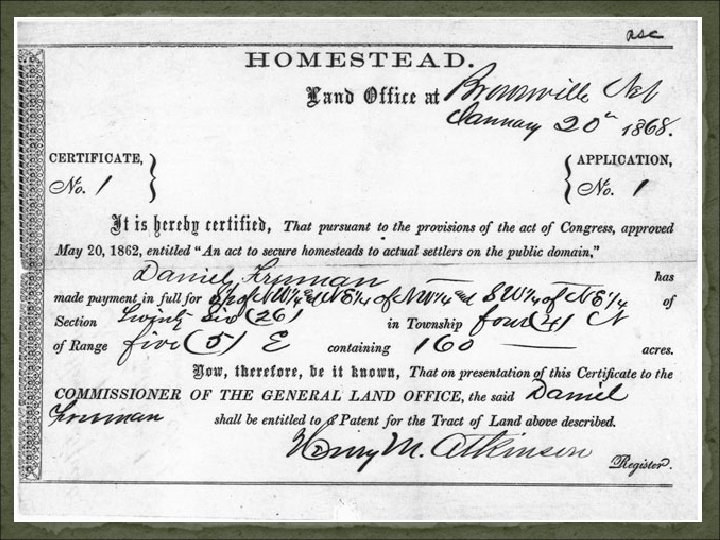

On January 1, 1863, Daniel Freeman, a Union Army scout, was scheduled to leave Gage County, Nebraska Territory, to report for duty in St. Louis. At a New Year's Eve party the night before, Freeman met some local Land Office officials and convinced a clerk to open the office shortly after midnight in order to file a land claim. In doing so, Freeman became one of the first to take advantage of the opportunities provided by the Homestead Act, a law signed by President Abraham Lincoln on May 20, 1862

The new law established a three-fold homestead acquisition process: filing an application, improving the land, and filing for deed of title. Any U. S. citizen, or intended citizen, who had never borne arms against the U. S. Government could file an application and lay claim to 160 acres of surveyed Government land. For the next 5 years, the homesteader had to live on the land improve it by building a 12 -by-14 dwelling and growing crops. After 5 years, the homesteader could file for his patent (or deed of title) by submitting proof of residency and the required improvements to a local land office.

On January 1, 1863, Daniel Freeman and 417 others filed claims. Many more pioneers followed, populating the land, building towns and schools and creating new states from the territories. In 1936, the Department of the Interior recognized Freeman as the first claimant and established the Homestead National Monument, near a school built in 1872, on his homestead near Beatrice, Nebraska. By 1934, over 1. 6 million homestead applications were processed and more than 270 million acres— 10 percent of all U. S. lands—passed into the hands of individuals.

By the end of the Civil War, fifteen thousand homestead claims had been established, and more followed in the postwar years. Donner Party • How did homesteaders get to their new homes? • Wagon trains • Covered wagons

Westward Expansion Adding new territory Map of areas settled by the Act

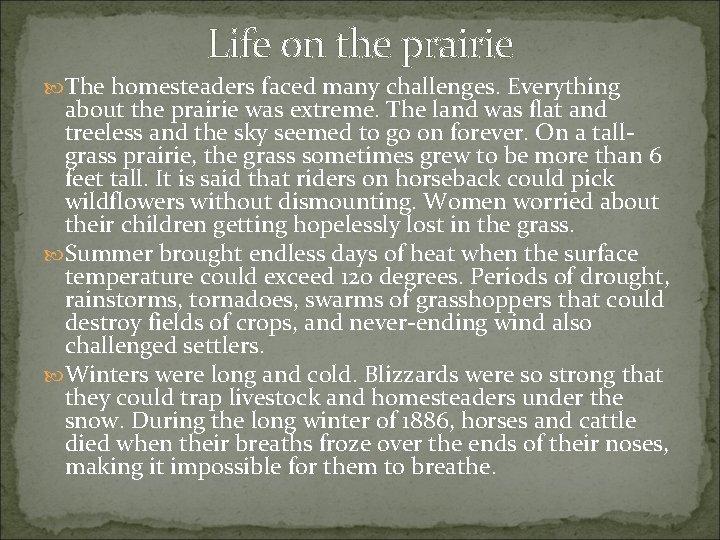

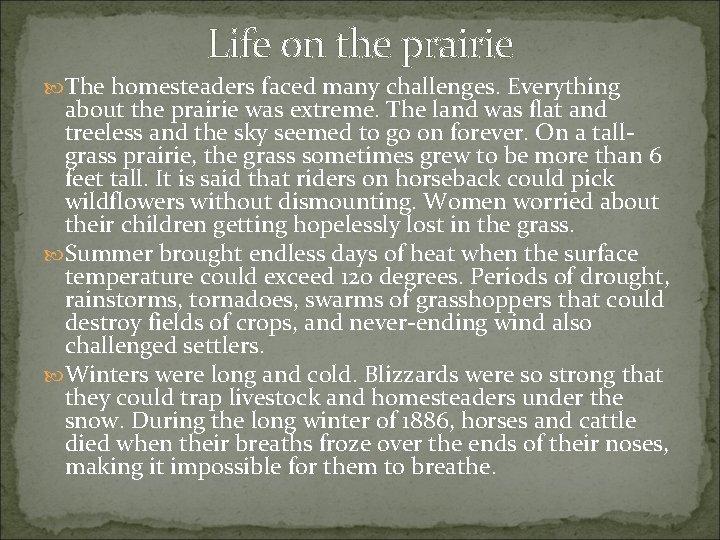

Life on the prairie The homesteaders faced many challenges. Everything about the prairie was extreme. The land was flat and treeless and the sky seemed to go on forever. On a tallgrass prairie, the grass sometimes grew to be more than 6 feet tall. It is said that riders on horseback could pick wildflowers without dismounting. Women worried about their children getting hopelessly lost in the grass. Summer brought endless days of heat when the surface temperature could exceed 120 degrees. Periods of drought, rainstorms, tornadoes, swarms of grasshoppers that could destroy fields of crops, and never-ending wind also challenged settlers. Winters were long and cold. Blizzards were so strong that they could trap livestock and homesteaders under the snow. During the long winter of 1886, horses and cattle died when their breaths froze over the ends of their noses, making it impossible for them to breathe.

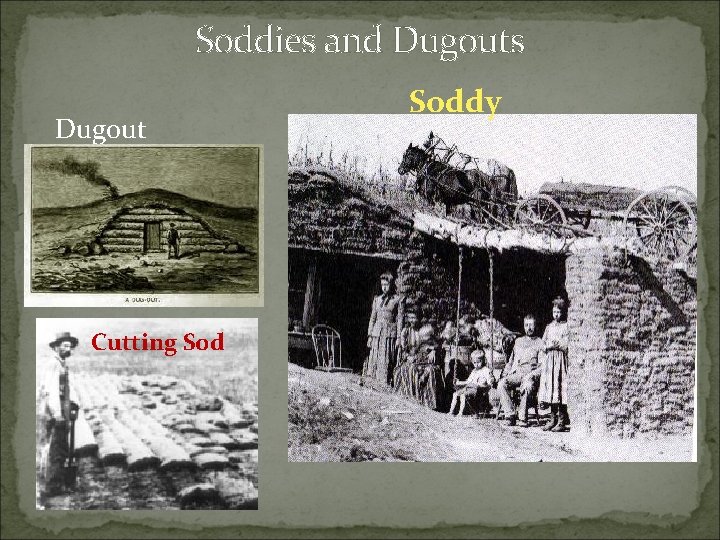

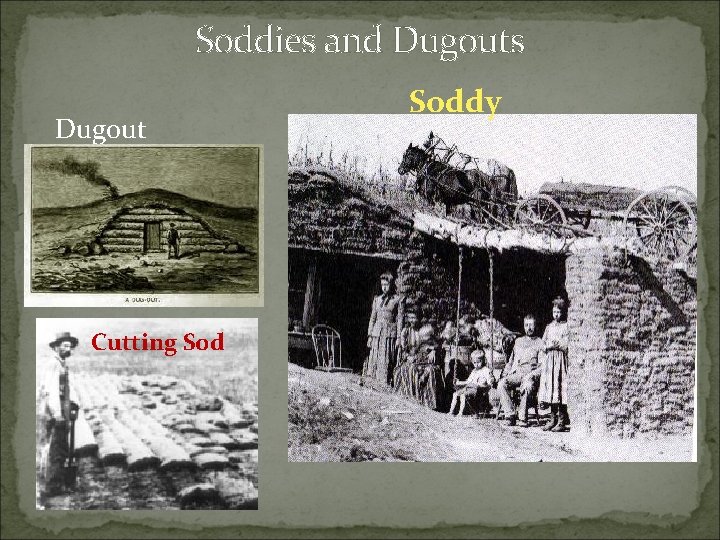

Making a house Without trees or stone to build with, homesteaders had to rely on the only available building material — prairie sod, jokingly called "Nebraska marble. " Sod is the top layer of earth that includes grass, its roots, and the dirt clinging to the roots. Building a sod house was a lot of work and often took many weeks, especially if the settler's nearest neighbors were too far away or unable to help. Building a Soddie

Dugouts Because tents or the top of a covered wagon provided little comfort or shelter from the prairie's wild weather, many settlers began by building dugouts. Dugouts were small, dark spaces dug into the side of a hill that could be made quickly and were much warmer and drier than tents. Many people built a sod house right in front of the dugout and then used the dugout as another room.

Soddies and Dugouts Dugout Cutting Soddy

The Prarie Driving on I 70 Santa Fe Trail