History of Astronomy Unit 1 B Essential Questions

History of Astronomy Unit 1 B

Essential Questions • How did the ancients describe the place of the Earth? • How did Copernican astronomers solve the puzzle of planetary motion? • How does gravity explain orbital motion? • How did Einstein refine the understanding of motion and gravity?

Standards SAST 4. Students analyze the dynamic nature of astronomy by comparing and contrasting evidence supporting current views of the universe with historical views. a. Evaluate the impact that technological advances, as an agent of change, have had on our modern view of the solar system and universe. b. Explain the relevance of experimental contributions of scientists to the advancement of the field of astronomy.

Outline I. The Roots of Astronomy A. Archaeoastronomy B. The Astronomy of Greece C. The Ptolemaic Universe II. The Copernican Revolution A. Copernicus B. Galileo Galilei III. The Puzzle of Planetary Motion A. Johannes Kepler IV. Galileo and Newton A. Galileo and Motion B. Newton and the Laws of Motion C. Mutual Gravitation

Outline V. Orbital Motion A. Orbital Motion B. Newton's Version of Kepler's Third Law VI. Einstein and Relativity A. Special Relativity B. The General Theory of Relativity C. Confirmation of the Curvature of Space-Time

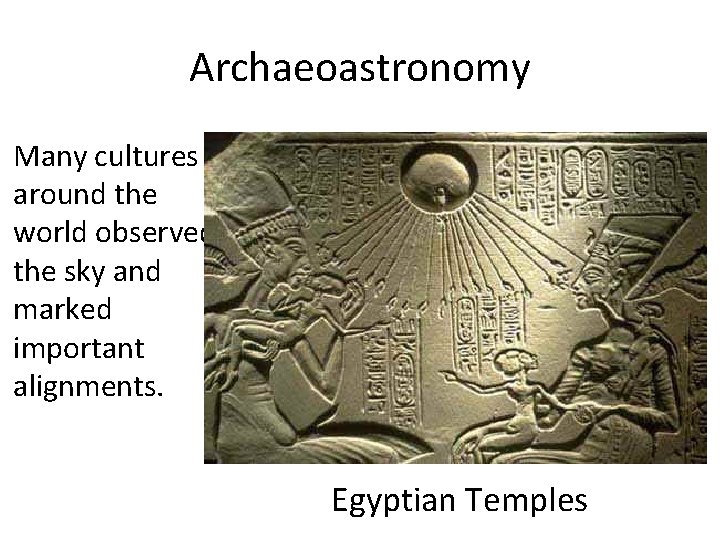

Archaeoastronomy is the study of the astronomy of ancient peoples. Mayans Egyptians

Archaeoastronomy Many cultures around the world observed the sky and marked important alignments. Egyptian Temples

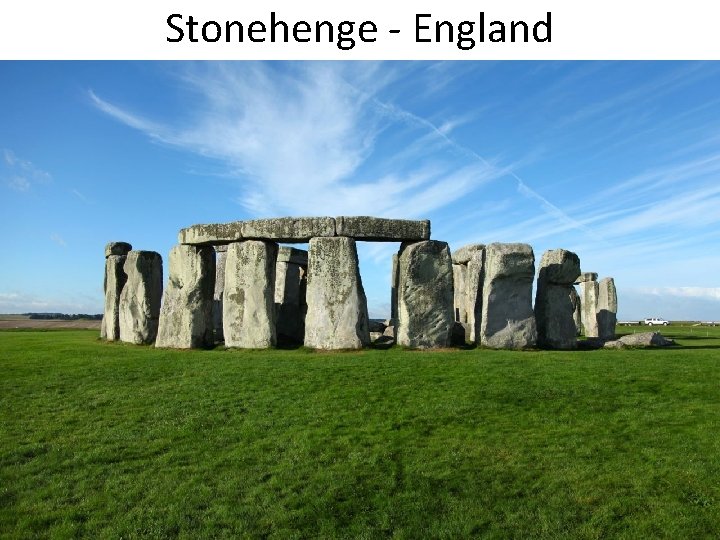

Stonehenge - England

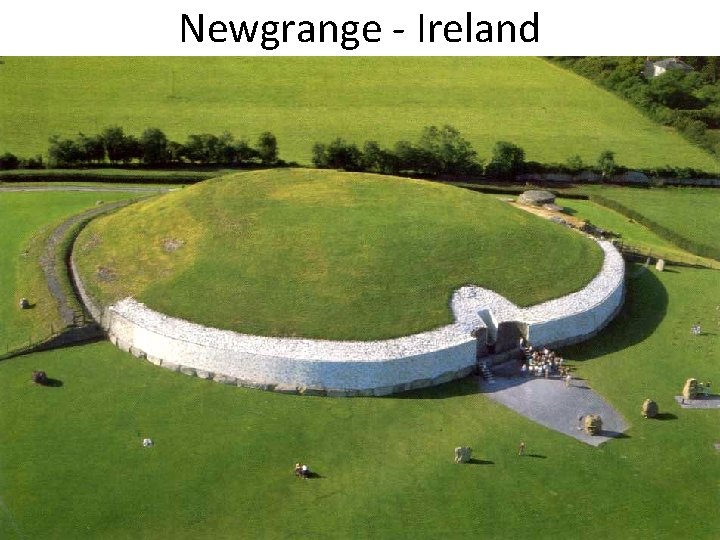

Newgrange - Ireland

The Sun Dagger – New Mexico

From Archaeoastronomy to the Astronomy of Greece • In most cases, ancient cultures, having no written language, left no detailed records of their astronomical beliefs. • Greek astronomy, derived in part from Babylon and Egypt, is better known because written documents have survived.

The Astronomy of Greece Greek models were generally wrong because they were based on these “first principles”, believed to be obvious and not questioned: 1. The Universe is Geocentric: Earth is the unmoving center of the Universe. 2. The heavens are perfect and the perfect shape is the sphere, so the heavens must be made of spheres*. * Plato, Pythagoras, and Aristotle all believed this and it went unquestioned for nearly 2000 years.

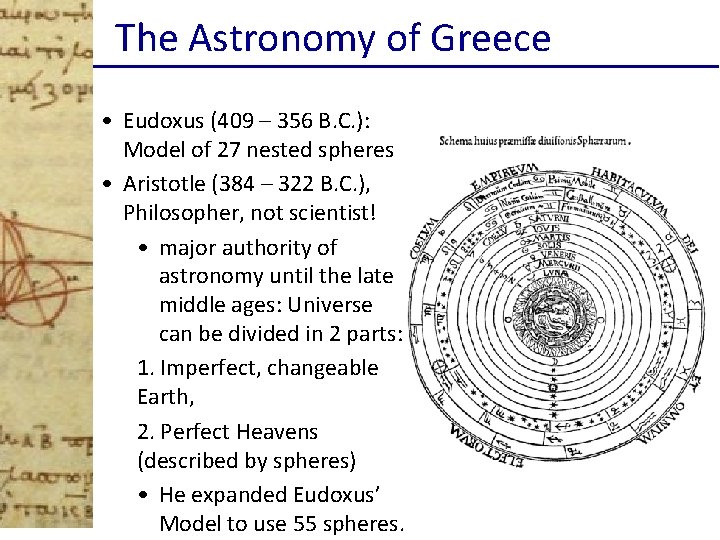

The Astronomy of Greece • Eudoxus (409 – 356 B. C. ): Model of 27 nested spheres • Aristotle (384 – 322 B. C. ), Philosopher, not scientist! • major authority of astronomy until the late middle ages: Universe can be divided in 2 parts: 1. Imperfect, changeable Earth, 2. Perfect Heavens (described by spheres) • He expanded Eudoxus’ Model to use 55 spheres.

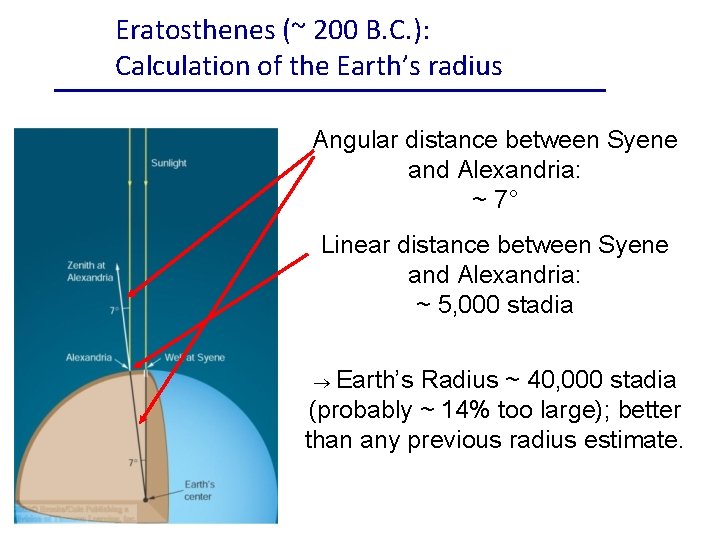

Eratosthenes (~ 200 B. C. ): Calculation of the Earth’s radius Angular distance between Syene and Alexandria: ~ 7° Linear distance between Syene and Alexandria: ~ 5, 000 stadia Earth’s Radius ~ 40, 000 stadia (probably ~ 14% too large); better than any previous radius estimate.

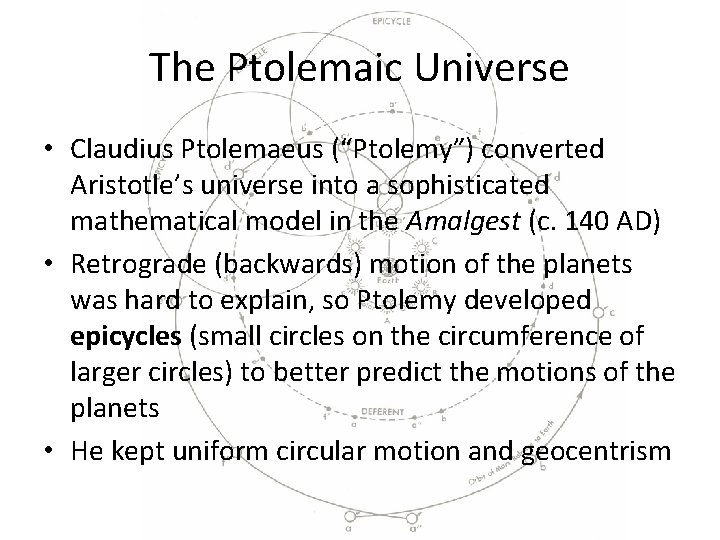

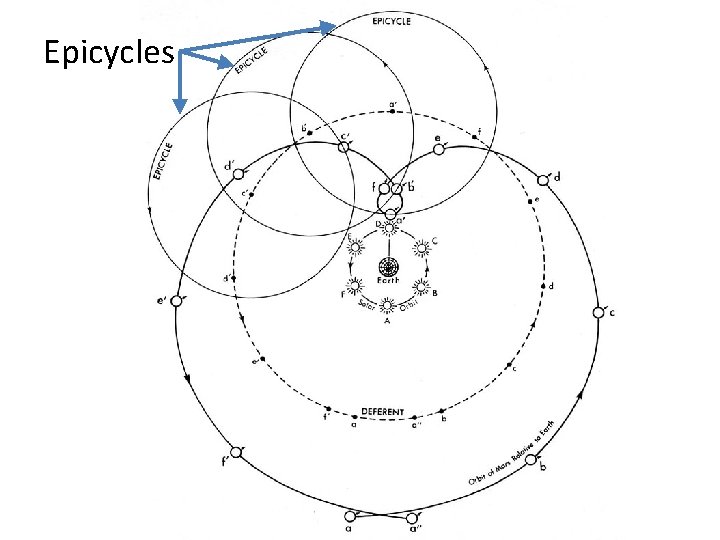

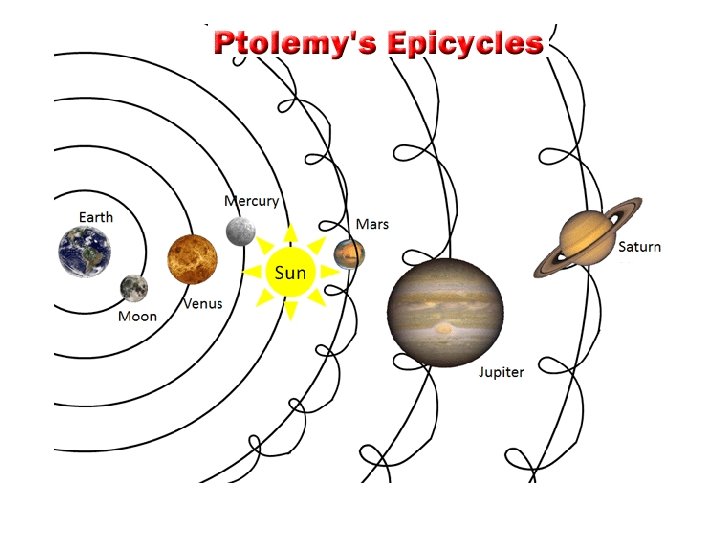

The Ptolemaic Universe • Claudius Ptolemaeus (“Ptolemy”) converted Aristotle’s universe into a sophisticated mathematical model in the Amalgest (c. 140 AD) • Retrograde (backwards) motion of the planets was hard to explain, so Ptolemy developed epicycles (small circles on the circumference of larger circles) to better predict the motions of the planets • He kept uniform circular motion and geocentrism

Epicycles

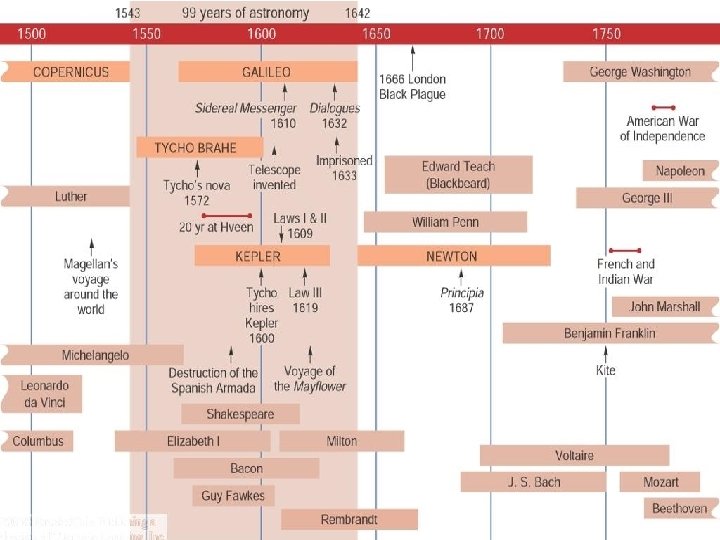

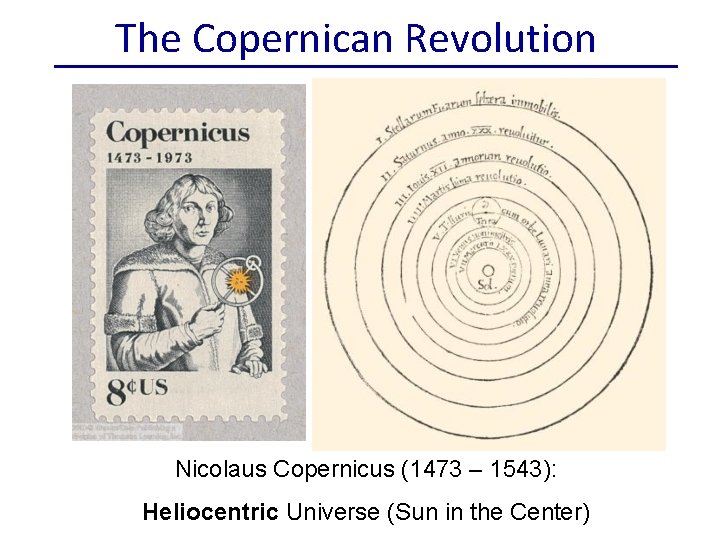

The Copernican Revolution Nicolaus Copernicus (1473 – 1543): Heliocentric Universe (Sun in the Center)

Copernicus the Revolutionary • Copernicus devised a heliocentric (suncentered) model. He preserved the principle of uniform circular motion, but he argued that Earth rotates on its axis and revolves around the sun once a year. • His theory was controversial because it contradicted Church teaching. • Copernicus published his theory in his book De Revolutionibus Orbium Coelestium in 1543, the same year he died.

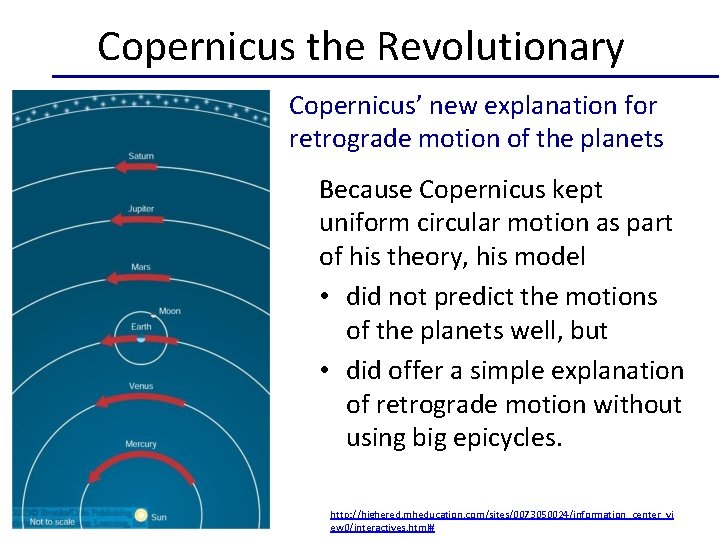

Copernicus the Revolutionary Copernicus’ new explanation for retrograde motion of the planets Because Copernicus kept uniform circular motion as part of his theory, his model • did not predict the motions of the planets well, but • did offer a simple explanation of retrograde motion without using big epicycles. http: //highered. mheducation. com/sites/0073050024/information_center_vi ew 0/interactives. html#

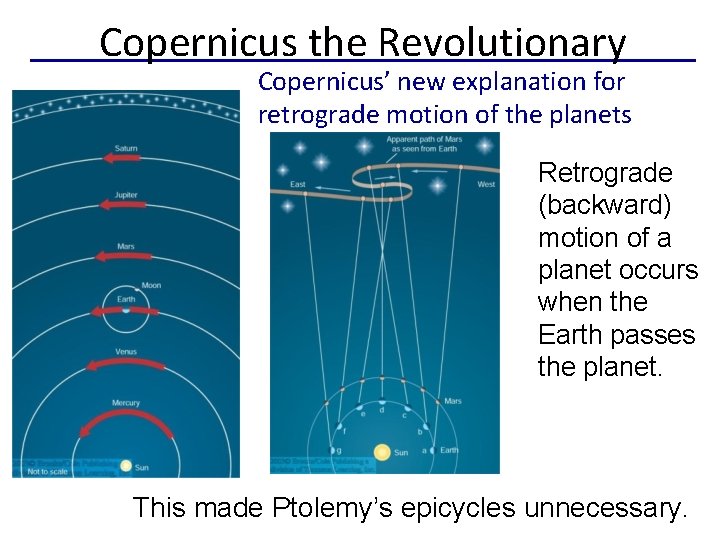

Copernicus the Revolutionary Copernicus’ new explanation for retrograde motion of the planets Retrograde (backward) motion of a planet occurs when the Earth passes the planet. This made Ptolemy’s epicycles unnecessary.

Galileo Galilei (1594 – 1642) • Invented the modern view of science: Transition from a faith-based “science” to an observation-based science. • Greatly improved on the newly invented telescope technology. (But Galileo did NOT invent the telescope!) • Was the first to meticulously report telescope observations of the sky to support the Copernican Model of the Universe. http: //www. history. com/topics/galileo-galilei

Johannes Kepler (1571 – 1630) • Used the precise observational tables of Tycho Brahe (1546 – 1601) to study planetary motion mathematically. • Found a consistent description by abandoning both 1. Circular motion and 2. Uniform motion. • Developed Kepler’s 3 Laws of Planetary Motion

Johannes Kepler (1571 – 1630) • Used the precise observational tables of Tycho Brahe (1546 – 1601) to study planetary motion mathematically. • Found a consistent description by abandoning both X 1. Circular motion and 2. Uniform motion. • Developed Kepler’s 3 Laws of Planetary Motion

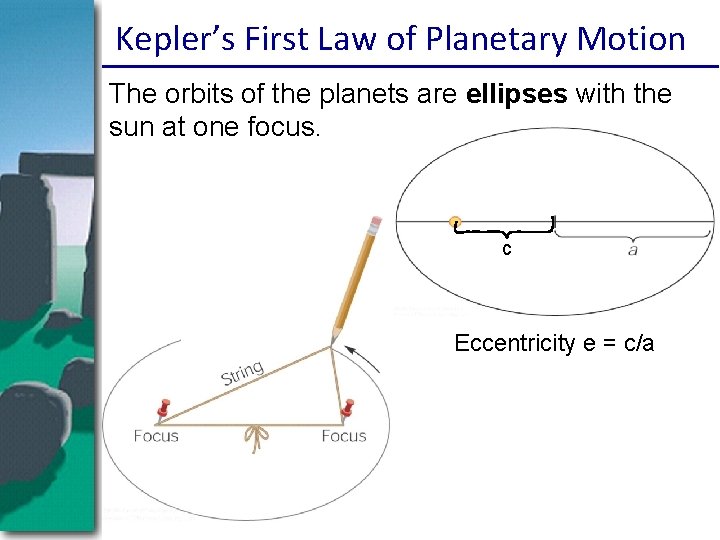

Kepler’s First Law of Planetary Motion The orbits of the planets are ellipses with the sun at one focus. c Eccentricity e = c/a

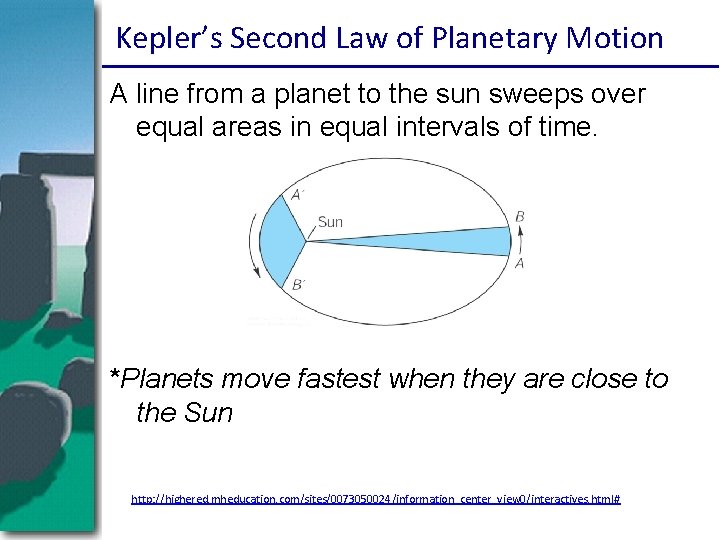

Kepler’s Second Law of Planetary Motion A line from a planet to the sun sweeps over equal areas in equal intervals of time. *Planets move fastest when they are close to the Sun http: //highered. mheducation. com/sites/0073050024/information_center_view 0/interactives. html#

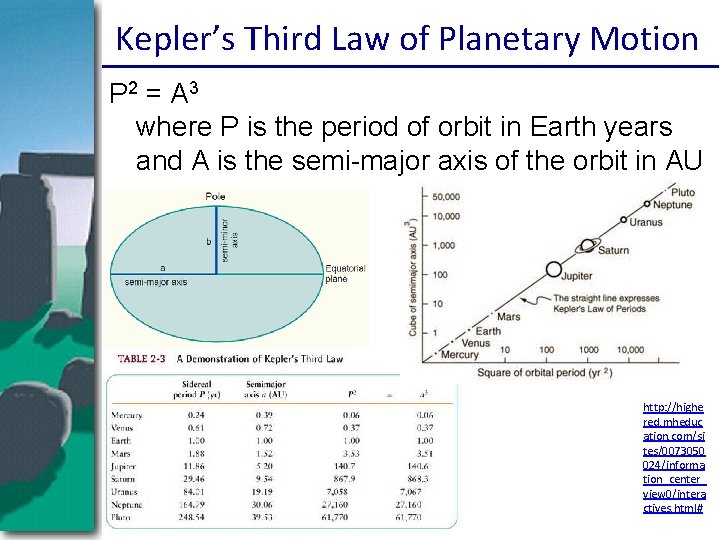

Kepler’s Third Law of Planetary Motion P 2 = A 3 where P is the period of orbit in Earth years and A is the semi-major axis of the orbit in AU http: //highe red. mheduc ation. com/si tes/0073050 024/informa tion_center_ view 0/intera ctives. html#

A New Era of Science Mathematics as a tool for understanding physics

Isaac Newton (1643 - 1727) • Built on the results of Galileo and Kepler • Added physics interpretations to the mathematical descriptions of astronomy by Copernicus, Galileo and Kepler Major achievements: 1. Invented Calculus as a necessary tool to solve mathematical problems related to motion 2. Discovered the three laws of motion 3. Discovered the universal law of mutual gravitation

Isaac Newton (1643 - 1727) • Building on the results of Galileo and Kepler • Adding physics interpretations to the mathematical descriptions of astronomy by Copernicus, Galileo and Kepler Major achievements: 1. Invented Calculus as a necessary tool to solve mathematical problems related to motion 2. Discovered the three laws of motion 3. Discovered the universal law of mutual gravitation

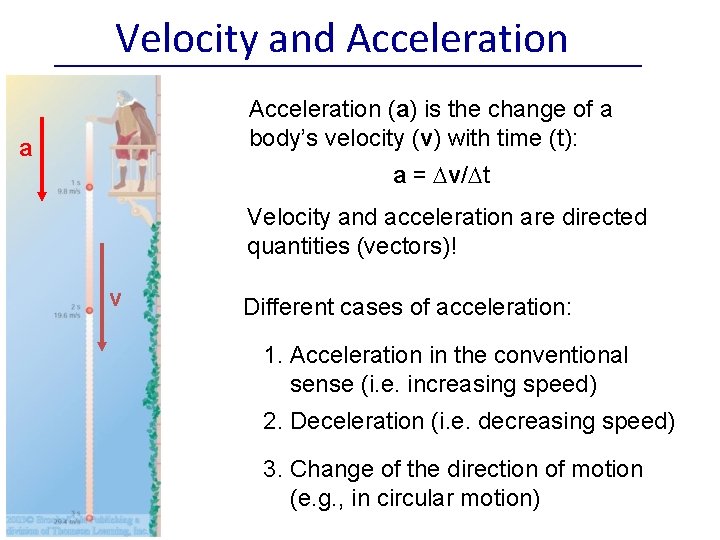

Velocity and Acceleration (a) is the change of a body’s velocity (v) with time (t): a a = Dv/Dt Velocity and acceleration are directed quantities (vectors)! v Different cases of acceleration: 1. Acceleration in the conventional sense (i. e. increasing speed) 2. Deceleration (i. e. decreasing speed) 3. Change of the direction of motion (e. g. , in circular motion)

Acceleration of Gravity Iron ball Wood ball Acceleration of gravity does not depend on the mass (or weight) of the falling object! 9. 8 m/s 2

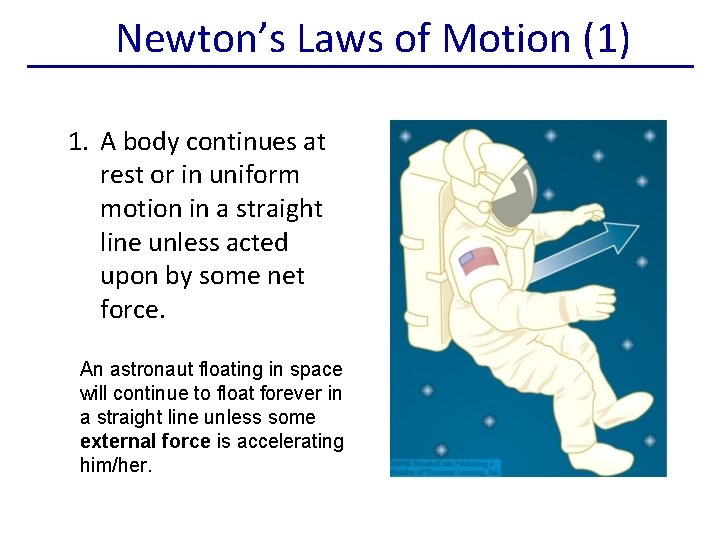

Newton’s Laws of Motion (1) 1. A body continues at rest or in uniform motion in a straight line unless acted upon by some net force. An astronaut floating in space will continue to float forever in a straight line unless some external force is accelerating him/her.

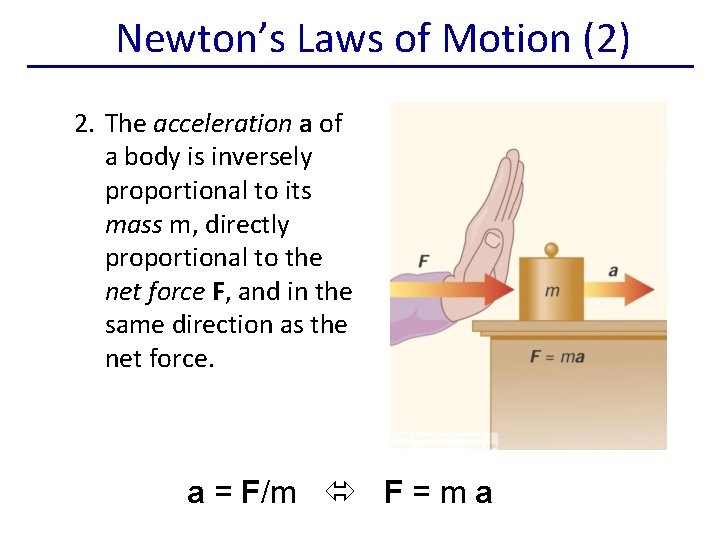

Newton’s Laws of Motion (2) 2. The acceleration a of a body is inversely proportional to its mass m, directly proportional to the net force F, and in the same direction as the net force. a = F/m F = m a

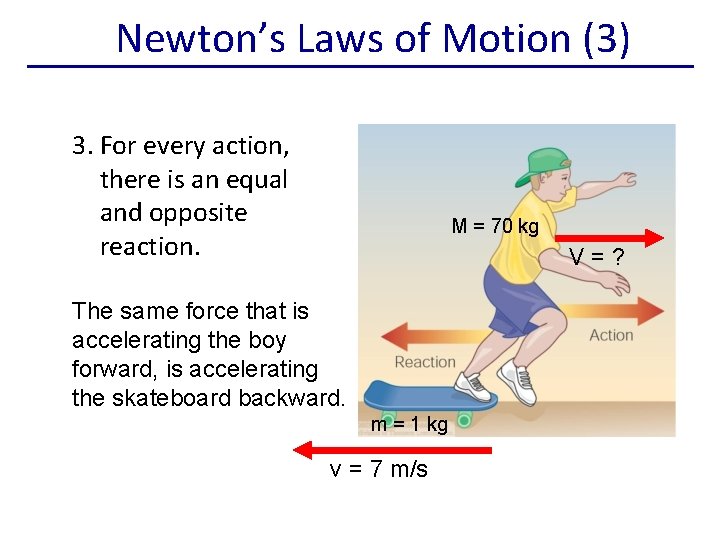

Newton’s Laws of Motion (3) 3. For every action, there is an equal and opposite reaction. M = 70 kg V=? The same force that is accelerating the boy forward, is accelerating the skateboard backward. m = 1 kg v = 7 m/s

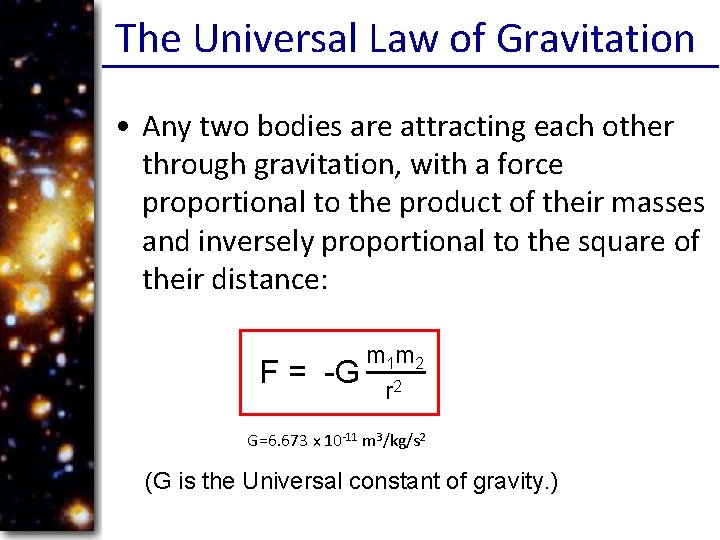

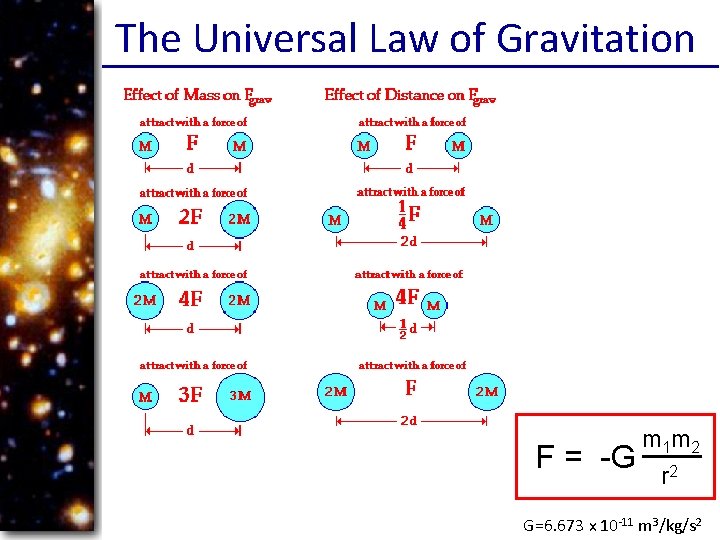

The Universal Law of Gravitation • Any two bodies are attracting each other through gravitation, with a force proportional to the product of their masses and inversely proportional to the square of their distance: F= m 1 m 2 -G 2 r G=6. 673 x 10 -11 m 3/kg/s 2 (G is the Universal constant of gravity. )

The Universal Law of Gravitation F = -G m 1 m 2 r 2 G=6. 673 x 10 -11 m 3/kg/s 2

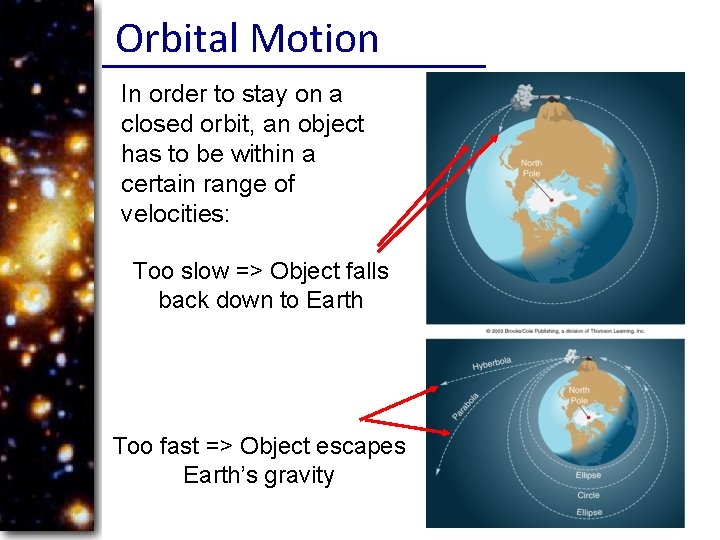

Orbital Motion In order to stay on a closed orbit, an object has to be within a certain range of velocities: Too slow => Object falls back down to Earth Too fast => Object escapes Earth’s gravity

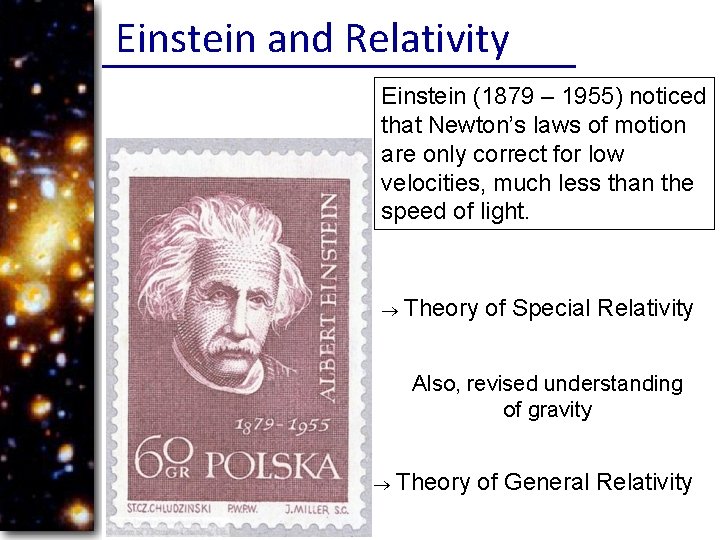

Einstein and Relativity Einstein (1879 – 1955) noticed that Newton’s laws of motion are only correct for low velocities, much less than the speed of light. Theory of Special Relativity Also, revised understanding of gravity Theory of General Relativity

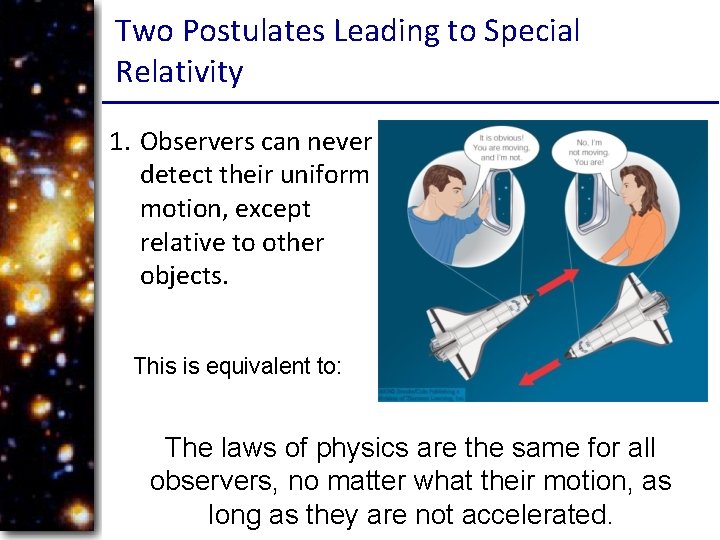

Two Postulates Leading to Special Relativity 1. Observers can never detect their uniform motion, except relative to other objects. This is equivalent to: The laws of physics are the same for all observers, no matter what their motion, as long as they are not accelerated.

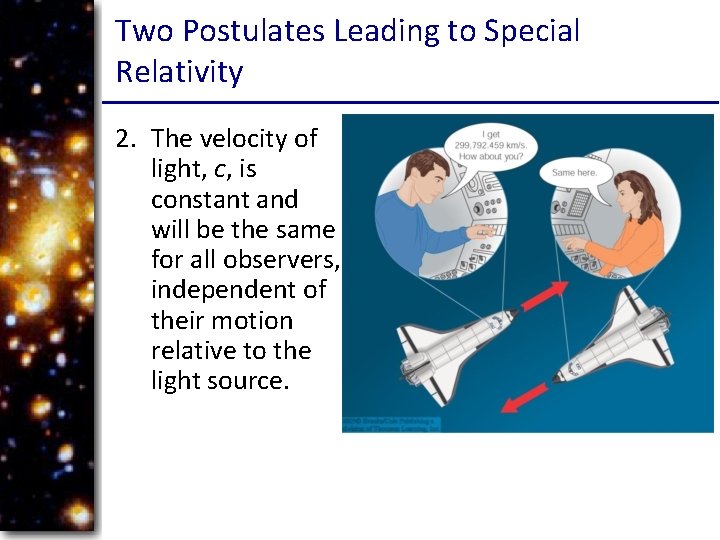

Two Postulates Leading to Special Relativity 2. The velocity of light, c, is constant and will be the same for all observers, independent of their motion relative to the light source.

Other Effects of Special Relativity • Mass increases: due to the mass-energy equivalence, KE added is converted to mass instead of v • Distances contract: Length scales on a rapidly moving object appear shortened. • Time moves slower: an effect called time dilation • The energy of a body at rest is not 0. Instead, we find E = mc 2

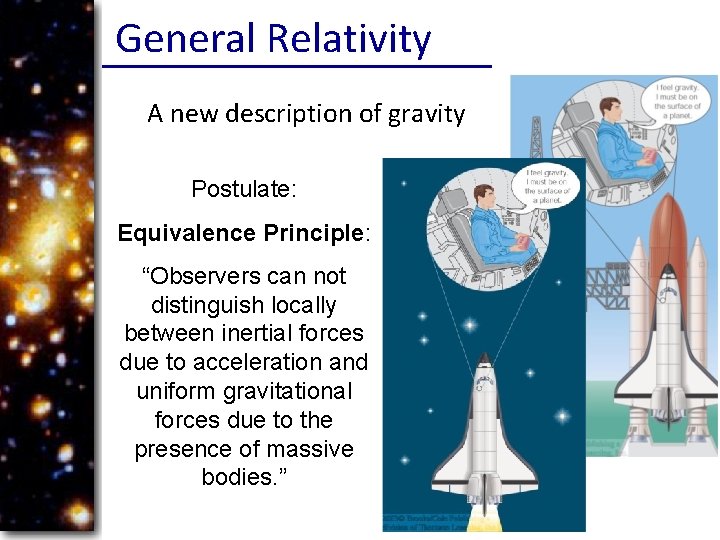

General Relativity A new description of gravity Postulate: Equivalence Principle: “Observers can not distinguish locally between inertial forces due to acceleration and uniform gravitational forces due to the presence of massive bodies. ”

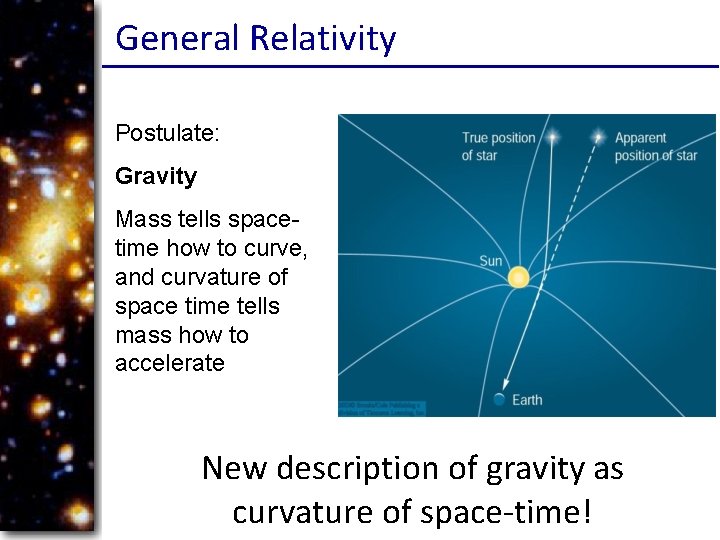

General Relativity Postulate: Gravity Mass tells spacetime how to curve, and curvature of space time tells mass how to accelerate New description of gravity as curvature of space-time!

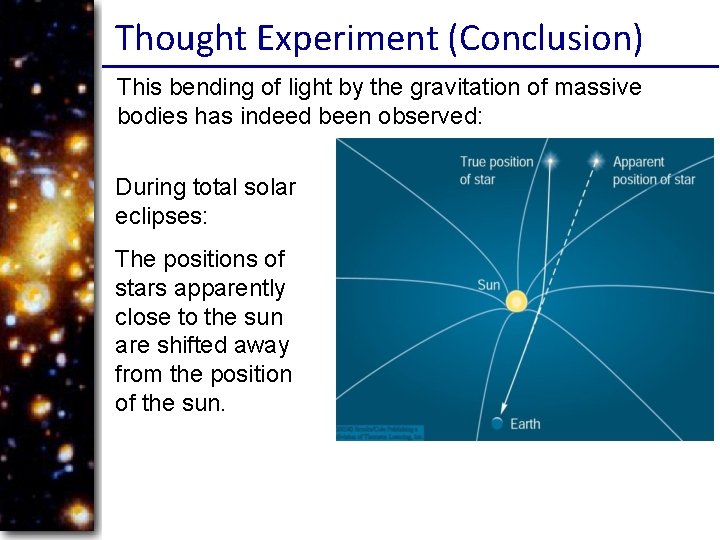

Thought Experiment (Conclusion) This bending of light by the gravitation of massive bodies has indeed been observed: During total solar eclipses: The positions of stars apparently close to the sun are shifted away from the position of the sun.

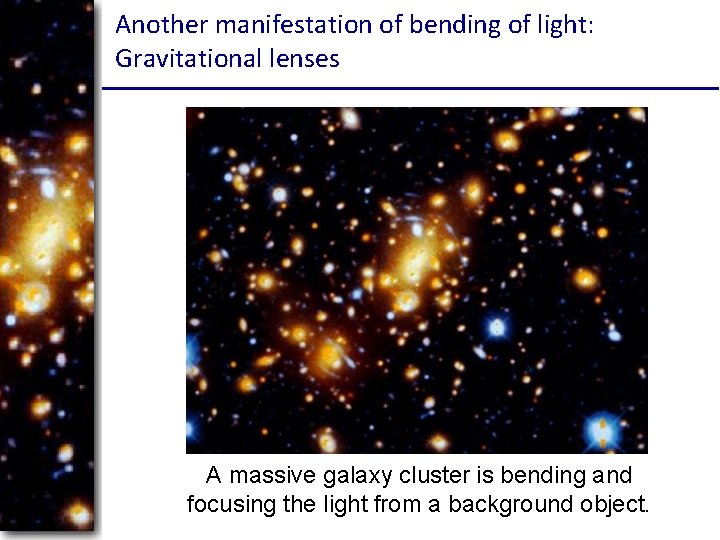

Another manifestation of bending of light: Gravitational lenses A massive galaxy cluster is bending and focusing the light from a background object.

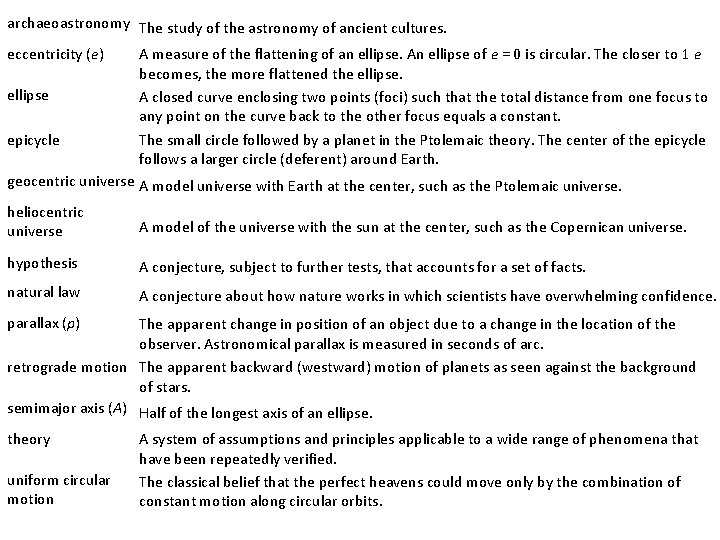

archaeoastronomy The study of the astronomy of ancient cultures. eccentricity (e) ellipse epicycle A measure of the flattening of an ellipse. An ellipse of e = 0 is circular. The closer to 1 e becomes, the more flattened the ellipse. A closed curve enclosing two points (foci) such that the total distance from one focus to any point on the curve back to the other focus equals a constant. The small circle followed by a planet in the Ptolemaic theory. The center of the epicycle follows a larger circle (deferent) around Earth. geocentric universe A model universe with Earth at the center, such as the Ptolemaic universe. heliocentric universe A model of the universe with the sun at the center, such as the Copernican universe. hypothesis A conjecture, subject to further tests, that accounts for a set of facts. natural law A conjecture about how nature works in which scientists have overwhelming confidence. parallax (p) The apparent change in position of an object due to a change in the location of the observer. Astronomical parallax is measured in seconds of arc. retrograde motion The apparent backward (westward) motion of planets as seen against the background of stars. semimajor axis (A) Half of the longest axis of an ellipse. theory uniform circular motion A system of assumptions and principles applicable to a wide range of phenomena that have been repeatedly verified. The classical belief that the perfect heavens could move only by the combination of constant motion along circular orbits.

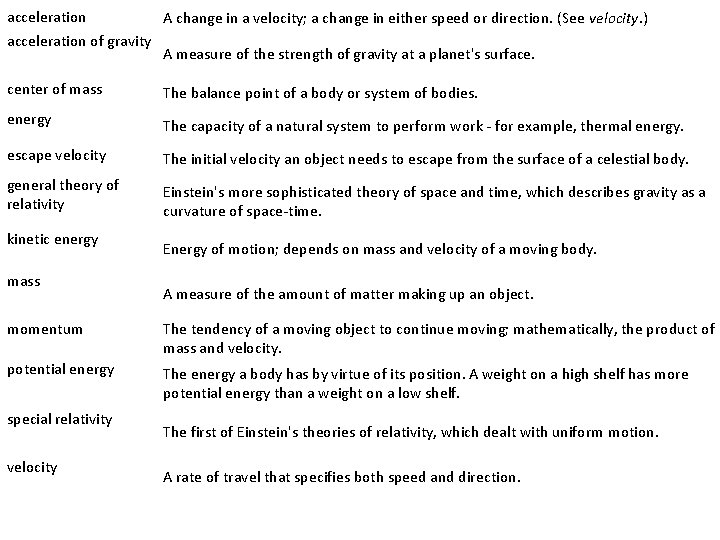

acceleration of gravity A change in a velocity; a change in either speed or direction. (See velocity. ) A measure of the strength of gravity at a planet's surface. center of mass The balance point of a body or system of bodies. energy The capacity of a natural system to perform work - for example, thermal energy. escape velocity The initial velocity an object needs to escape from the surface of a celestial body. general theory of relativity Einstein's more sophisticated theory of space and time, which describes gravity as a curvature of space-time. kinetic energy mass Energy of motion; depends on mass and velocity of a moving body. A measure of the amount of matter making up an object. momentum The tendency of a moving object to continue moving; mathematically, the product of mass and velocity. potential energy The energy a body has by virtue of its position. A weight on a high shelf has more potential energy than a weight on a low shelf. special relativity velocity The first of Einstein's theories of relativity, which dealt with uniform motion. A rate of travel that specifies both speed and direction.

- Slides: 49