Historical overview Linear and Circular accelerators Introduction of

- Slides: 26

Historical overview Linear and Circular accelerators Introduction of the basic principles of acceleration and a review of the historical development of accelerators, both linear and circular. Rick Baartman TRIUMF baartman@triumf. ca, (604) 222 -7343 2019 -01 -10 R. Baartman, UBC Phys 560 and UVic Phys 522, lecture 1 1

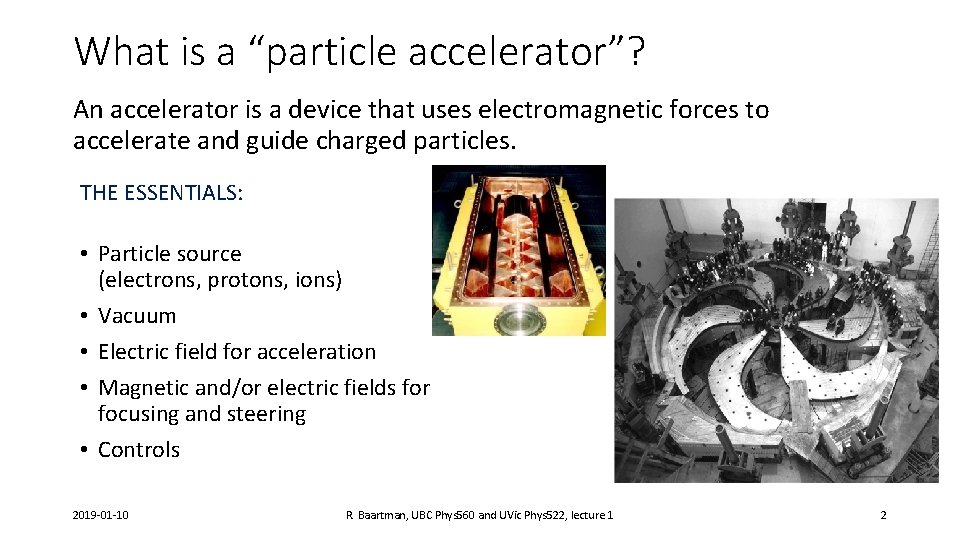

What is a “particle accelerator”? An accelerator is a device that uses electromagnetic forces to accelerate and guide charged particles. THE ESSENTIALS: • Particle source (electrons, protons, ions) • Vacuum • Electric field for acceleration • Magnetic and/or electric fields for focusing and steering • Controls 2019 -01 -10 R. Baartman, UBC Phys 560 and UVic Phys 522, lecture 1 2

Why do we want to accelerate particles? • Need > 6 Me. V to even get past the Coulomb barrier and interact with a nucleus. • Need >100 Me. V to create new particles of mass ~100 Me. V, e. g. pi-mesons. • TRIUMF cyclotron is 500 Me. V. • Need colliding beams to reach masses much larger than projectile mass. (More on this later. ) 2019 -01 -10 R. Baartman, UBC Phys 560 and UVic Phys 522, lecture 1 3

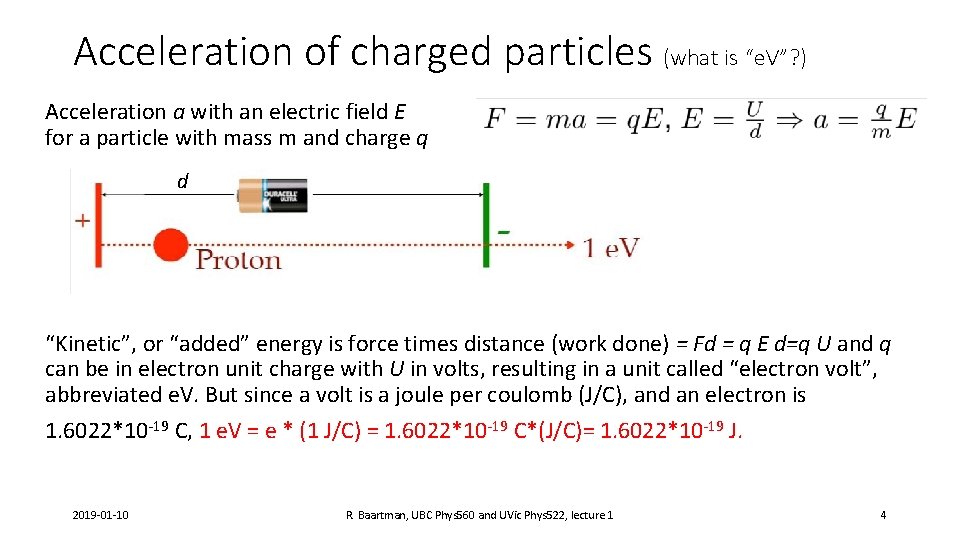

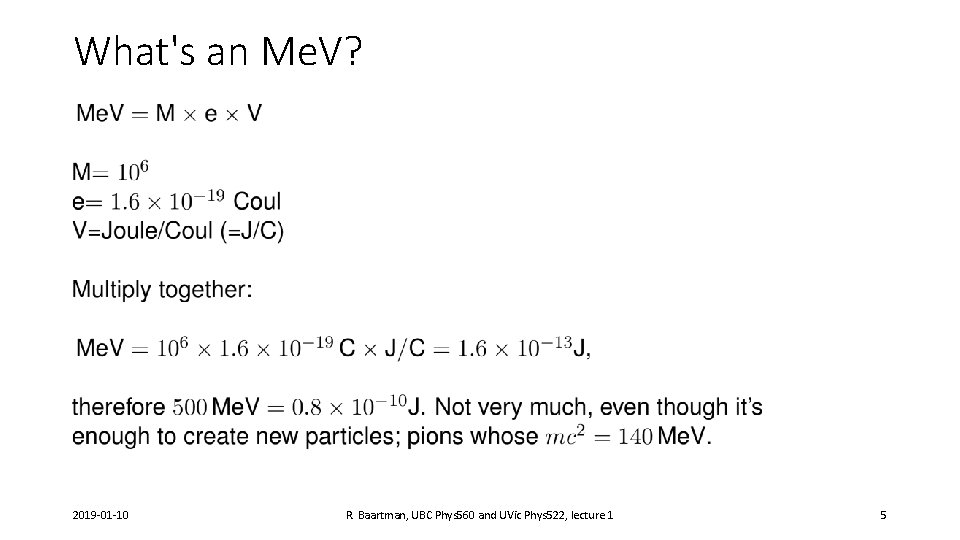

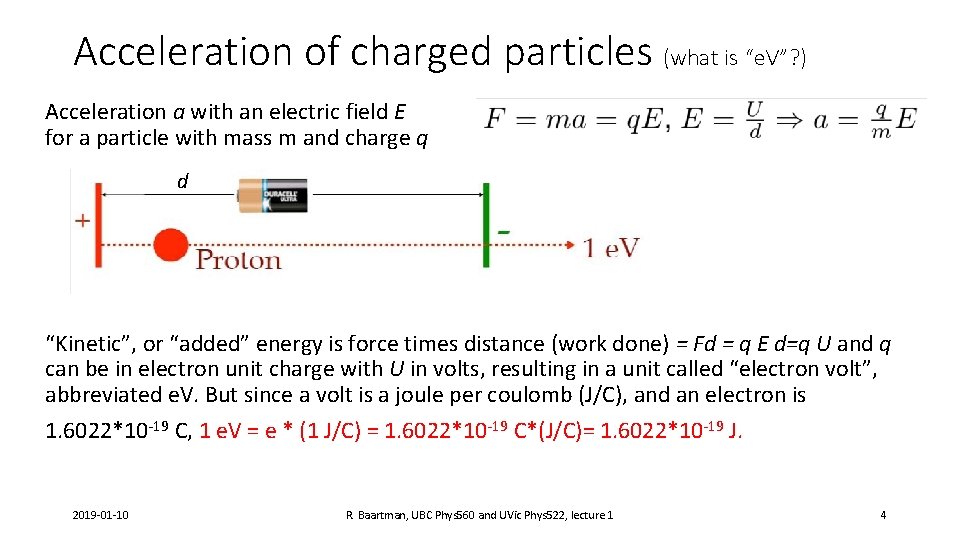

Acceleration of charged particles (what is “e. V”? ) Acceleration a with an electric field E for a particle with mass m and charge q d “Kinetic”, or “added” energy is force times distance (work done) = Fd = q E d=q U and q can be in electron unit charge with U in volts, resulting in a unit called “electron volt”, abbreviated e. V. But since a volt is a joule per coulomb (J/C), and an electron is 1. 6022*10 -19 C, 1 e. V = e * (1 J/C) = 1. 6022*10 -19 C*(J/C)= 1. 6022*10 -19 J. 2019 -01 -10 R. Baartman, UBC Phys 560 and UVic Phys 522, lecture 1 4

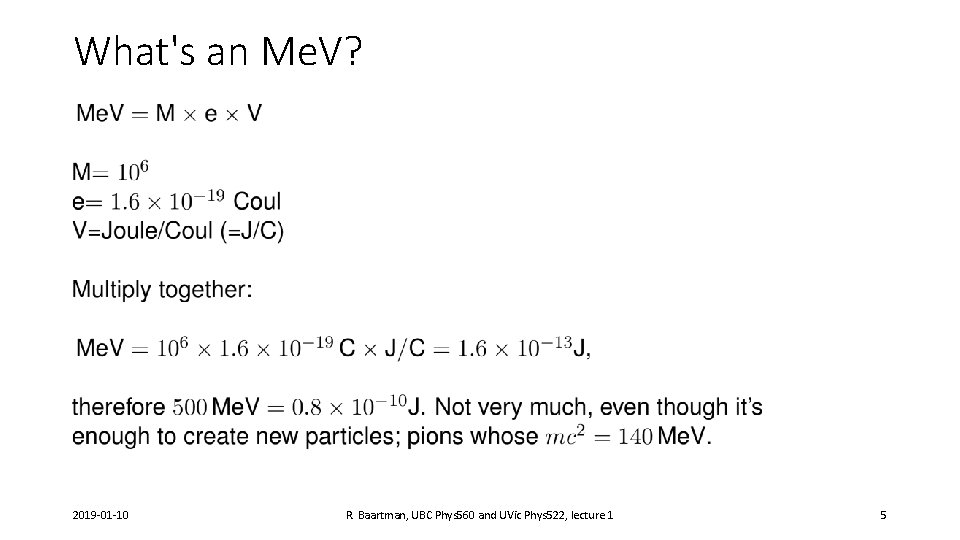

What's an Me. V? 2019 -01 -10 R. Baartman, UBC Phys 560 and UVic Phys 522, lecture 1 5

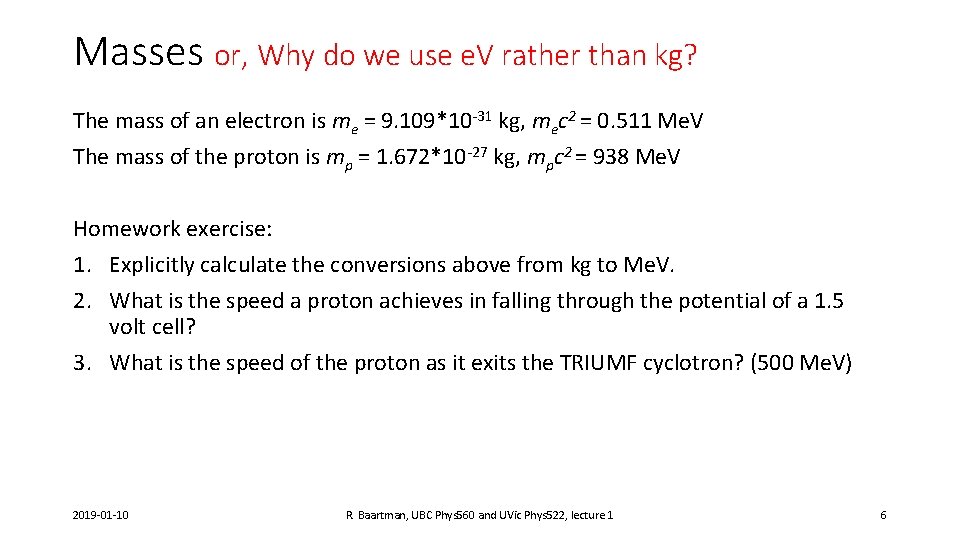

Masses or, Why do we use e. V rather than kg? The mass of an electron is me = 9. 109*10 -31 kg, mec 2 = 0. 511 Me. V The mass of the proton is mp = 1. 672*10 -27 kg, mpc 2 = 938 Me. V Homework exercise: 1. Explicitly calculate the conversions above from kg to Me. V. 2. What is the speed a proton achieves in falling through the potential of a 1. 5 volt cell? 3. What is the speed of the proton as it exits the TRIUMF cyclotron? (500 Me. V) 2019 -01 -10 R. Baartman, UBC Phys 560 and UVic Phys 522, lecture 1 6

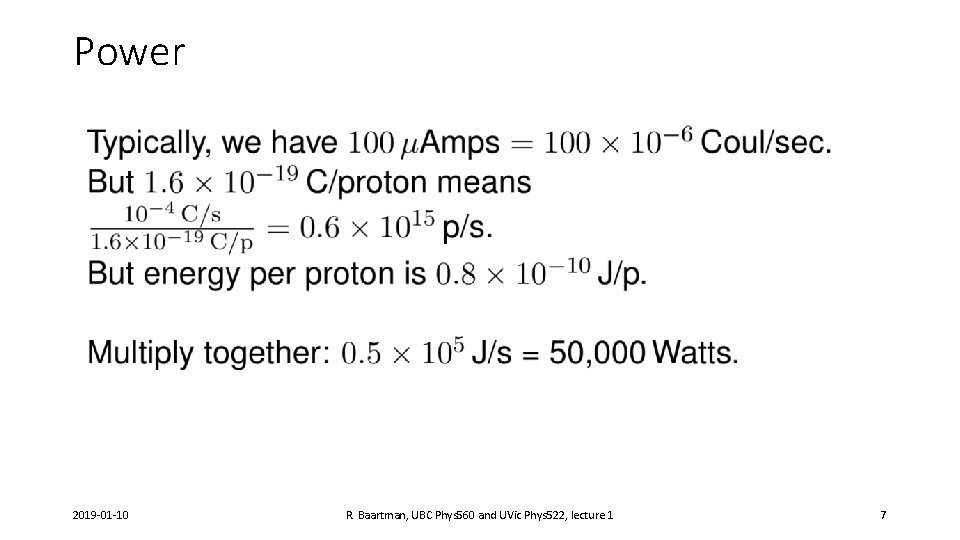

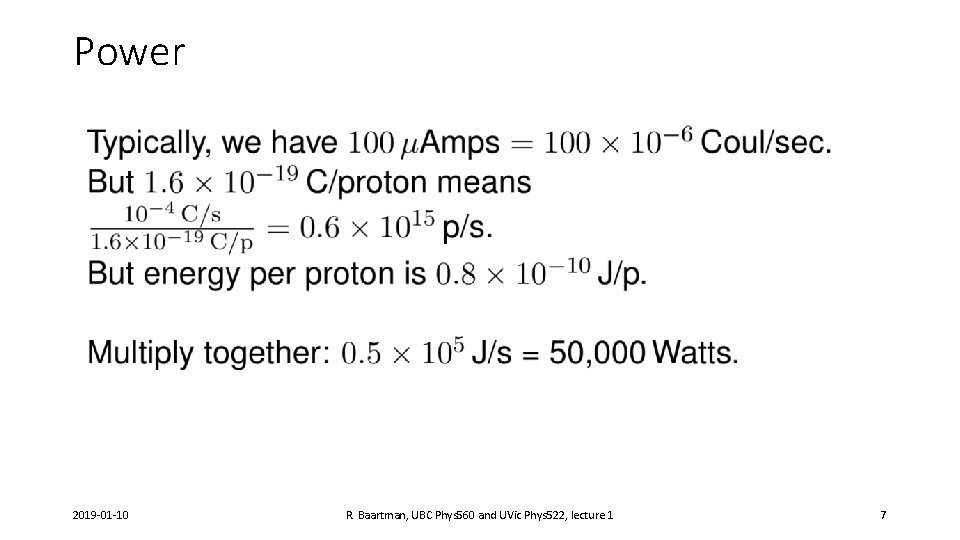

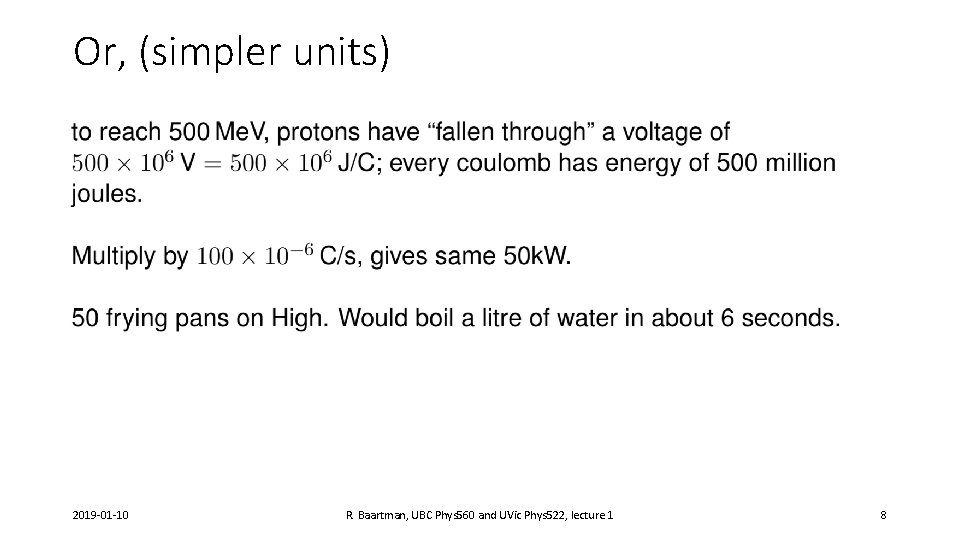

Power 2019 -01 -10 R. Baartman, UBC Phys 560 and UVic Phys 522, lecture 1 7

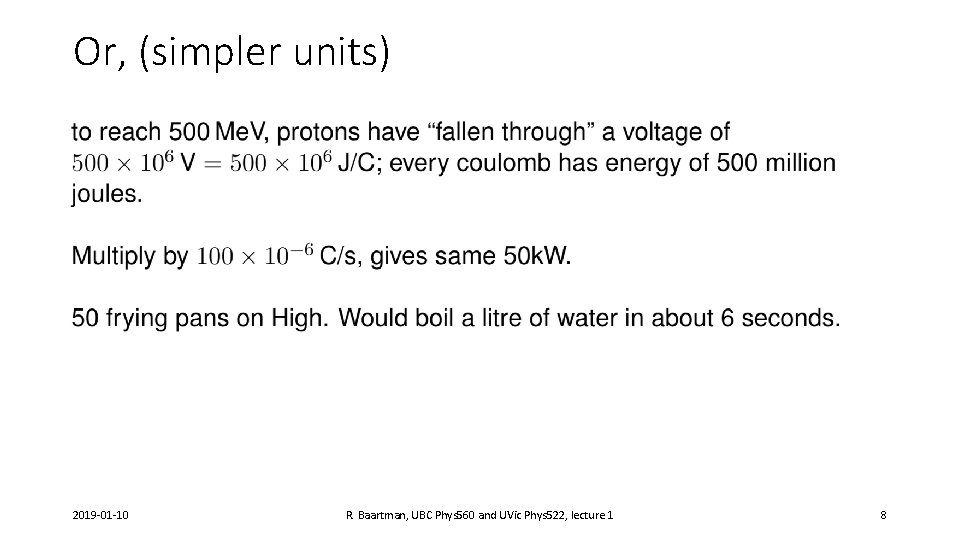

Or, (simpler units) 2019 -01 -10 R. Baartman, UBC Phys 560 and UVic Phys 522, lecture 1 8

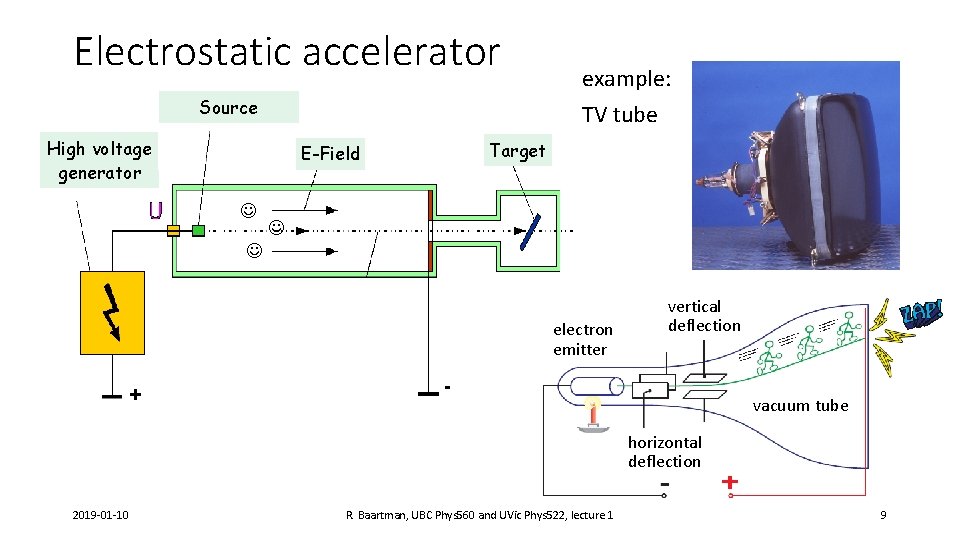

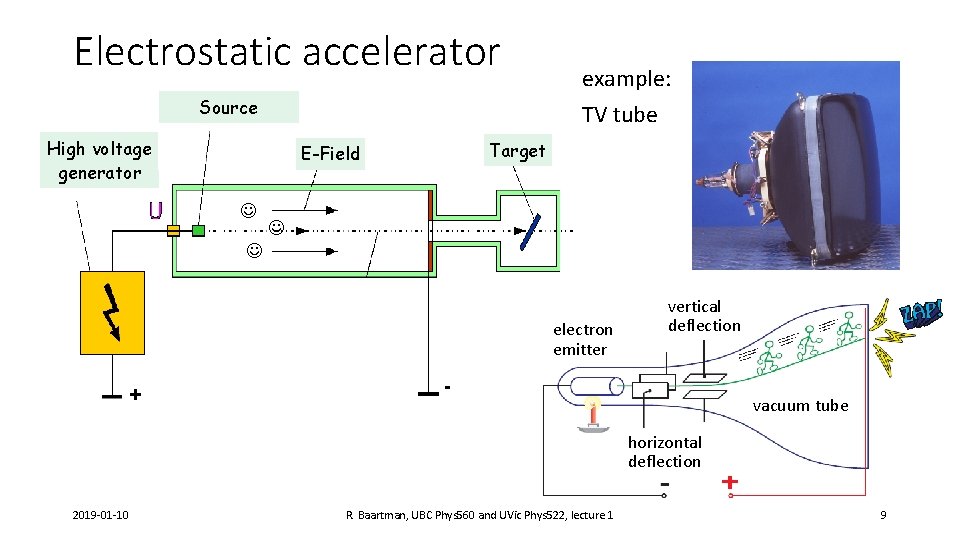

Electrostatic accelerator Source High voltage generator Target E-Field example: TV tube electron emitter + vertical deflection - vacuum tube horizontal deflection 2019 -01 -10 R. Baartman, UBC Phys 560 and UVic Phys 522, lecture 1 9

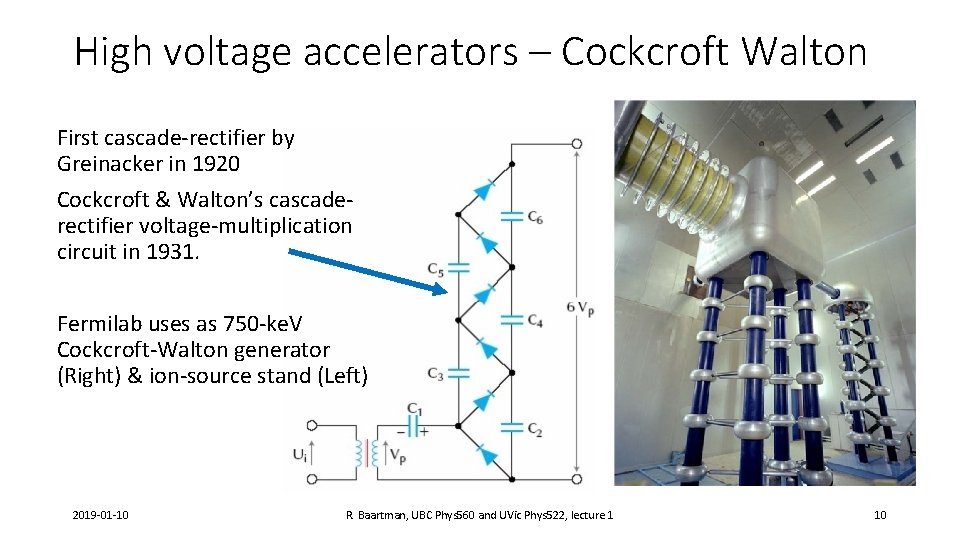

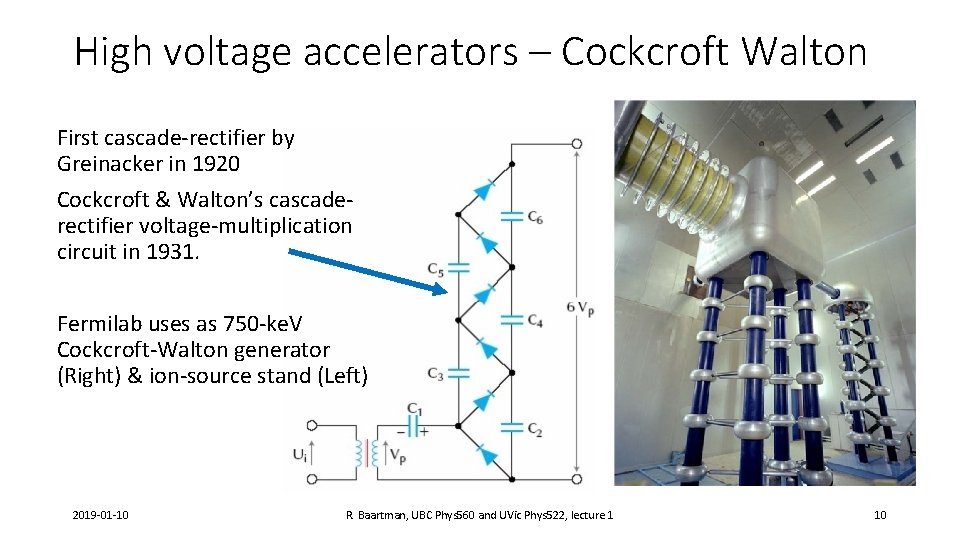

High voltage accelerators – Cockcroft Walton First cascade-rectifier by Greinacker in 1920 Cockcroft & Walton’s cascaderectifier voltage-multiplication circuit in 1931. Fermilab uses as 750 -ke. V Cockcroft-Walton generator (Right) & ion-source stand (Left) 2019 -01 -10 R. Baartman, UBC Phys 560 and UVic Phys 522, lecture 1 10

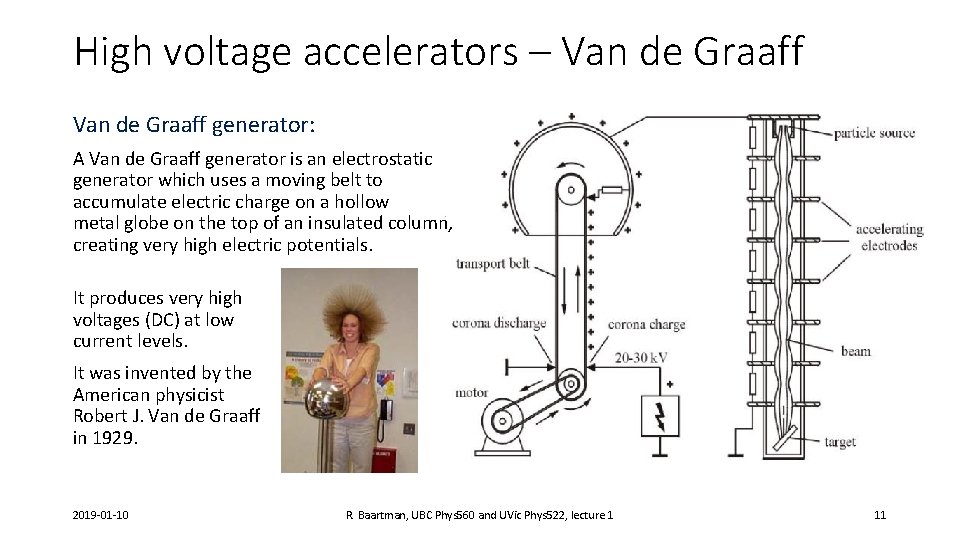

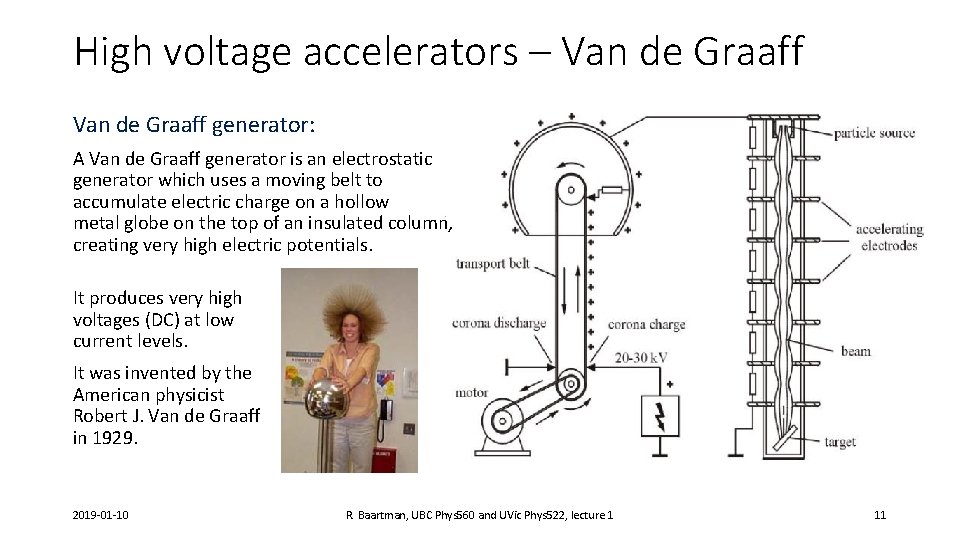

High voltage accelerators – Van de Graaff generator: A Van de Graaff generator is an electrostatic generator which uses a moving belt to accumulate electric charge on a hollow metal globe on the top of an insulated column, creating very high electric potentials. It produces very high voltages (DC) at low current levels. It was invented by the American physicist Robert J. Van de Graaff in 1929. 2019 -01 -10 R. Baartman, UBC Phys 560 and UVic Phys 522, lecture 1 11

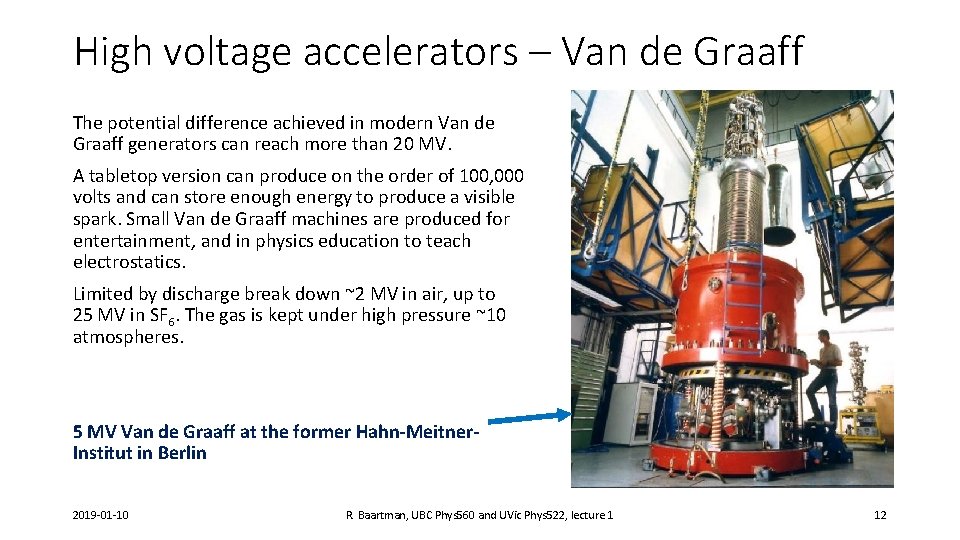

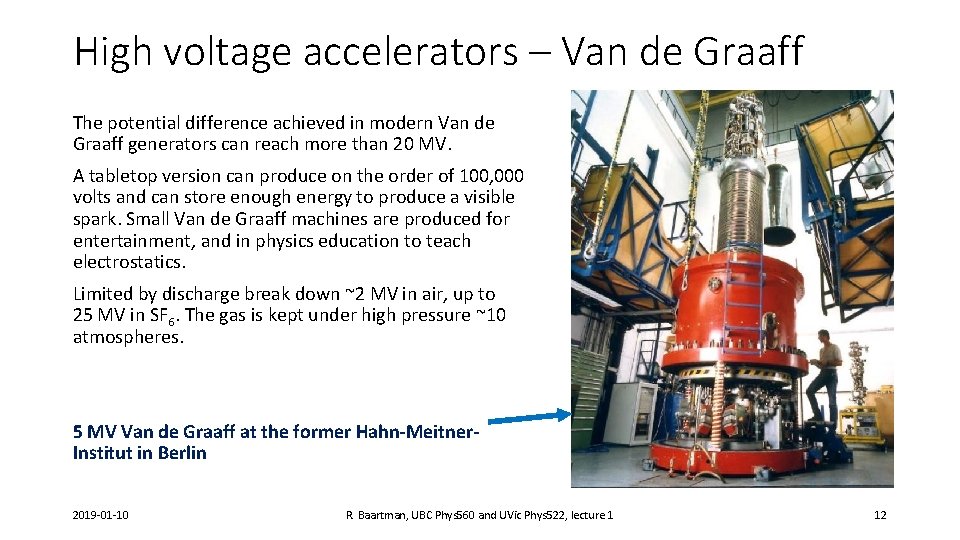

High voltage accelerators – Van de Graaff The potential difference achieved in modern Van de Graaff generators can reach more than 20 MV. A tabletop version can produce on the order of 100, 000 volts and can store enough energy to produce a visible spark. Small Van de Graaff machines are produced for entertainment, and in physics education to teach electrostatics. Limited by discharge break down ~2 MV in air, up to 25 MV in SF 6. The gas is kept under high pressure ~10 atmospheres. 5 MV Van de Graaff at the former Hahn-Meitner. Institut in Berlin 2019 -01 -10 R. Baartman, UBC Phys 560 and UVic Phys 522, lecture 1 12

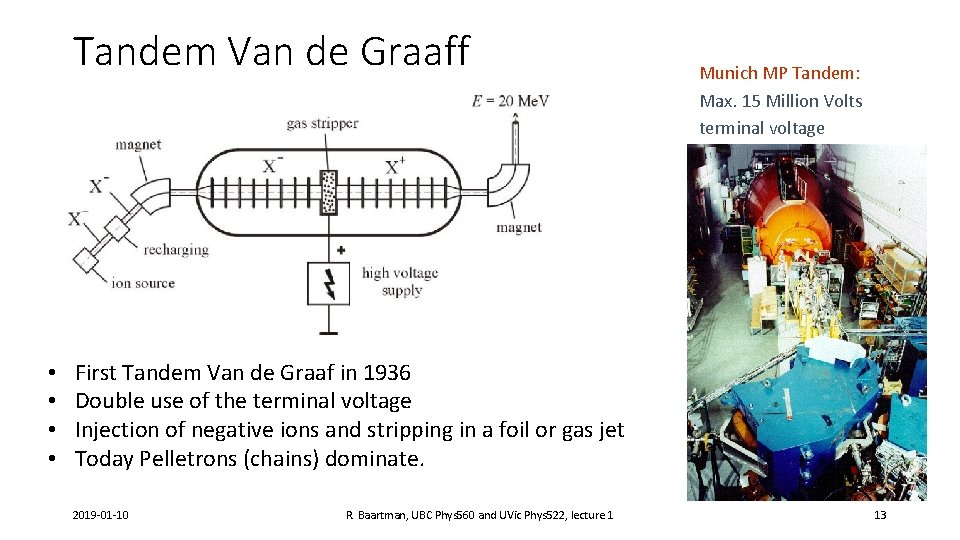

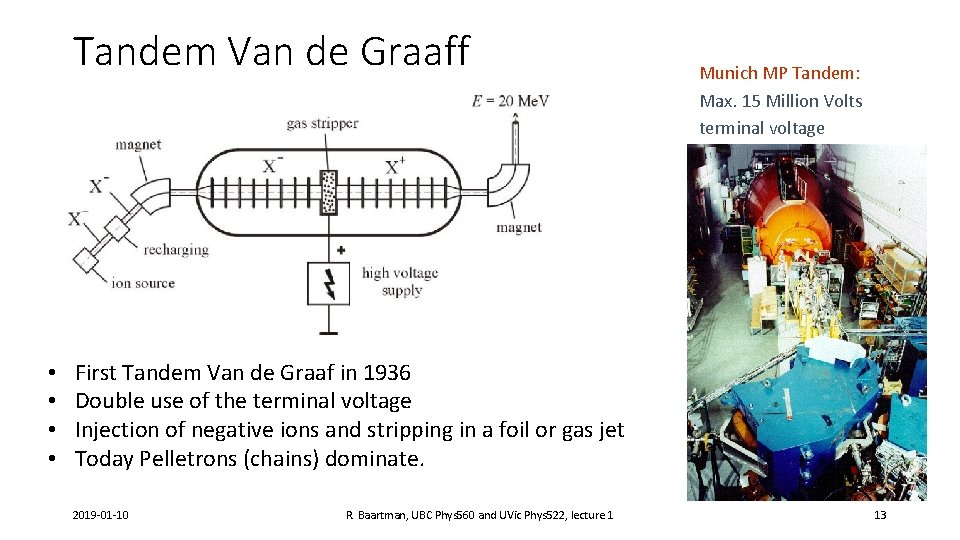

Tandem Van de Graaff • • Munich MP Tandem: Max. 15 Million Volts terminal voltage First Tandem Van de Graaf in 1936 Double use of the terminal voltage Injection of negative ions and stripping in a foil or gas jet Today Pelletrons (chains) dominate. 2019 -01 -10 R. Baartman, UBC Phys 560 and UVic Phys 522, lecture 1 13

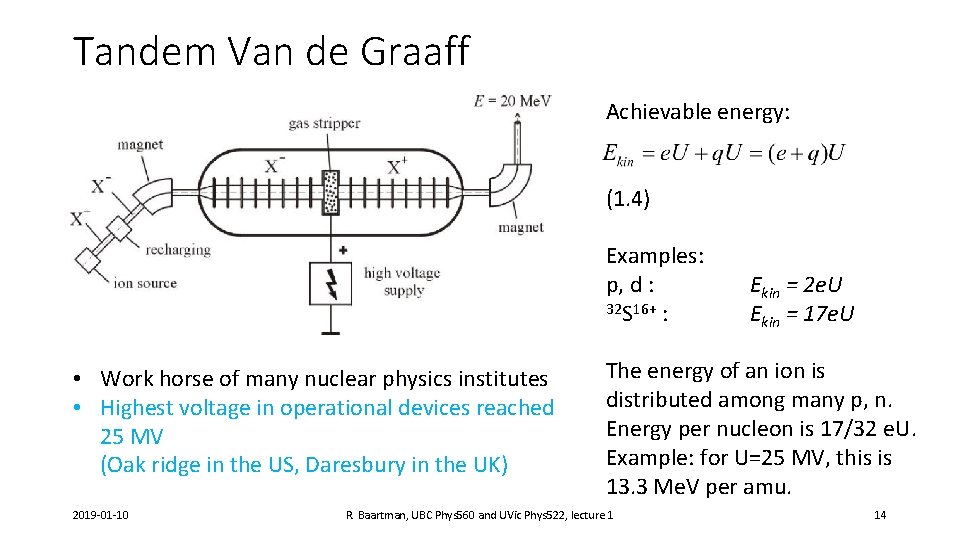

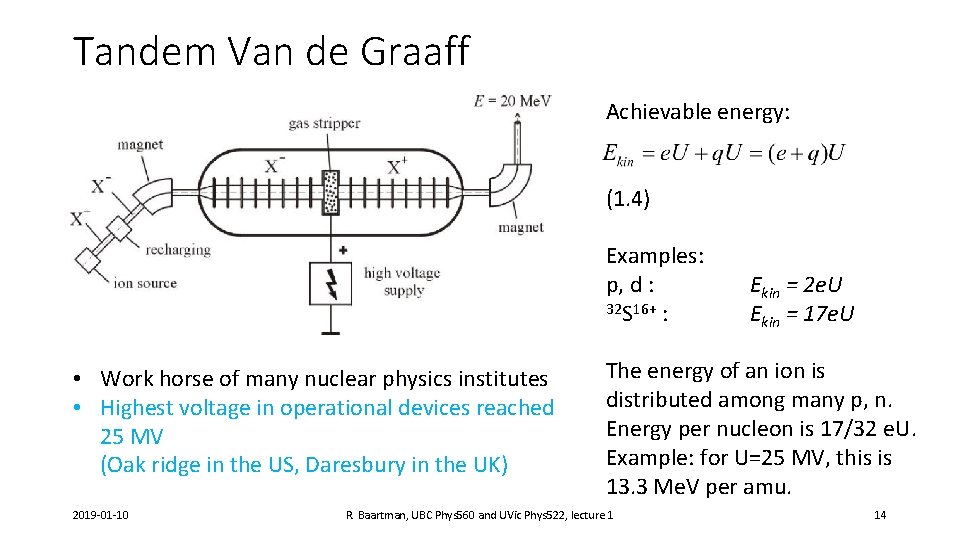

Tandem Van de Graaff Achievable energy: (1. 4) Examples: p, d : 32 S 16+ : • Work horse of many nuclear physics institutes • Highest voltage in operational devices reached 25 MV (Oak ridge in the US, Daresbury in the UK) 2019 -01 -10 Ekin = 2 e. U Ekin = 17 e. U The energy of an ion is distributed among many p, n. Energy per nucleon is 17/32 e. U. Example: for U=25 MV, this is 13. 3 Me. V per amu. R. Baartman, UBC Phys 560 and UVic Phys 522, lecture 1 14

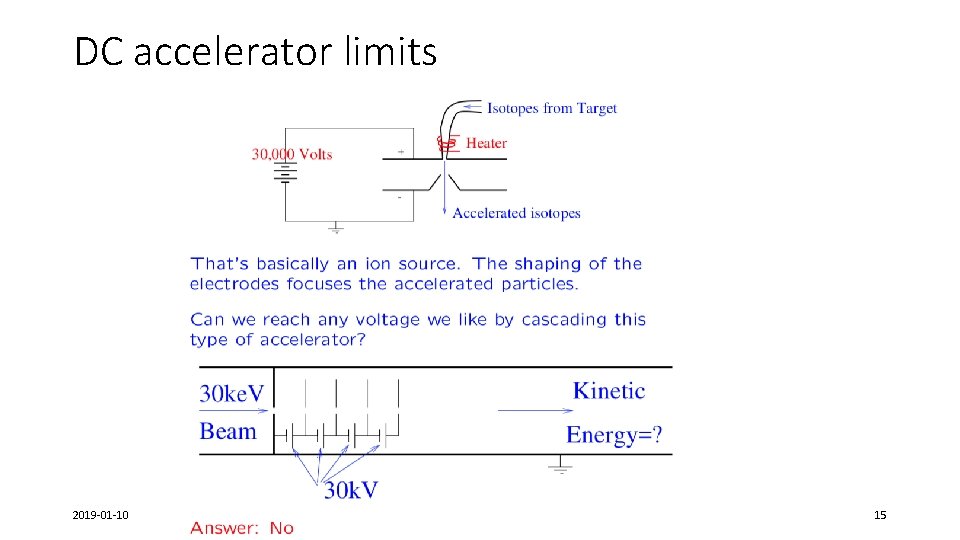

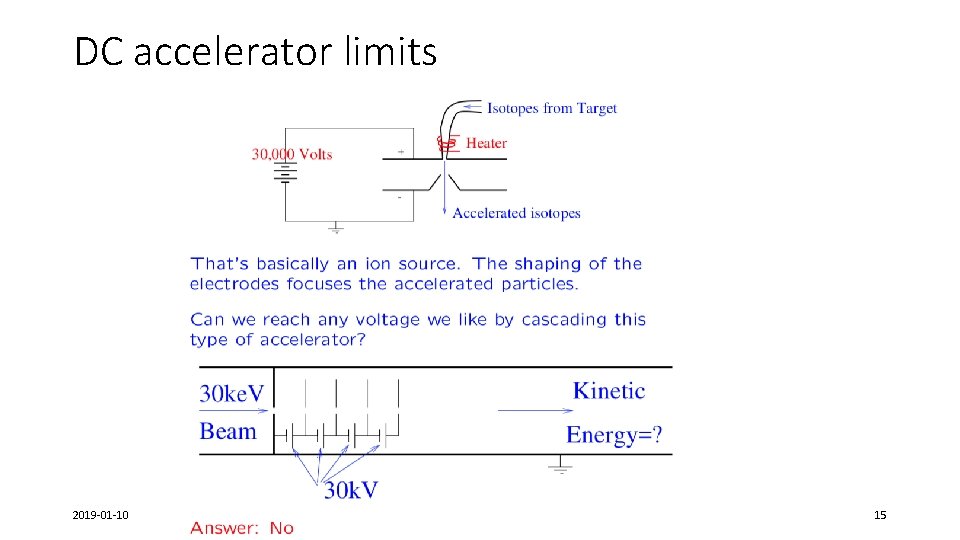

DC accelerator limits 2019 -01 -10 R. Baartman, UBC Phys 560 and UVic Phys 522, lecture 1 15

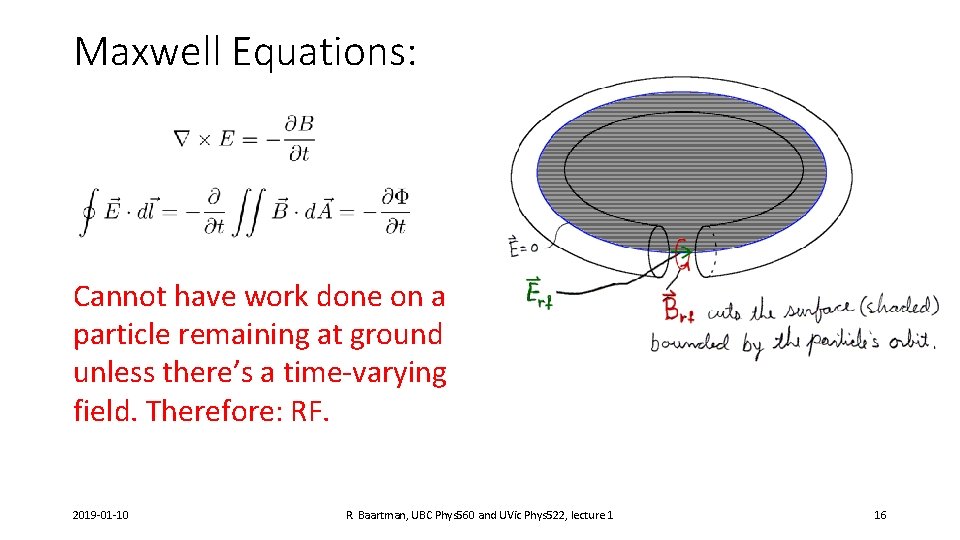

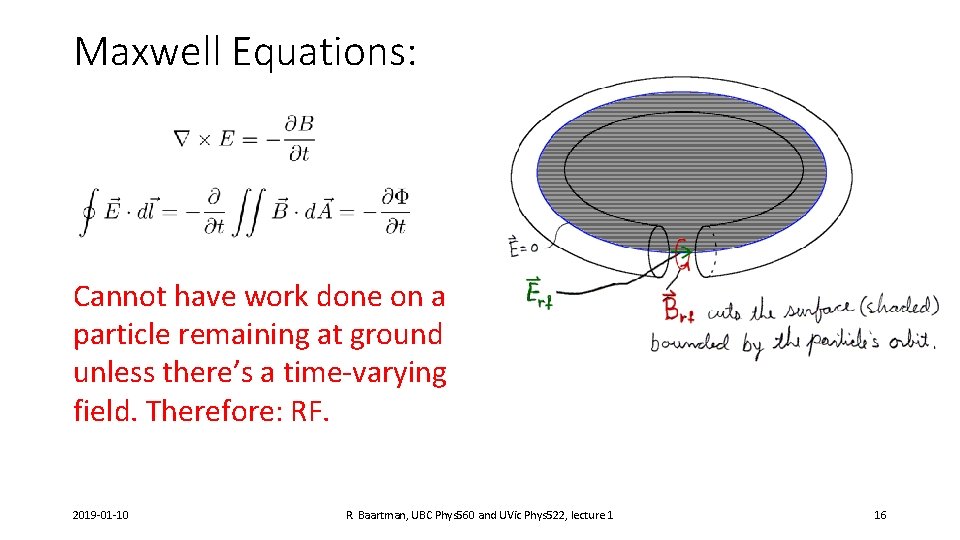

Maxwell Equations: Cannot have work done on a particle remaining at ground unless there’s a time-varying field. Therefore: RF. 2019 -01 -10 R. Baartman, UBC Phys 560 and UVic Phys 522, lecture 1 16

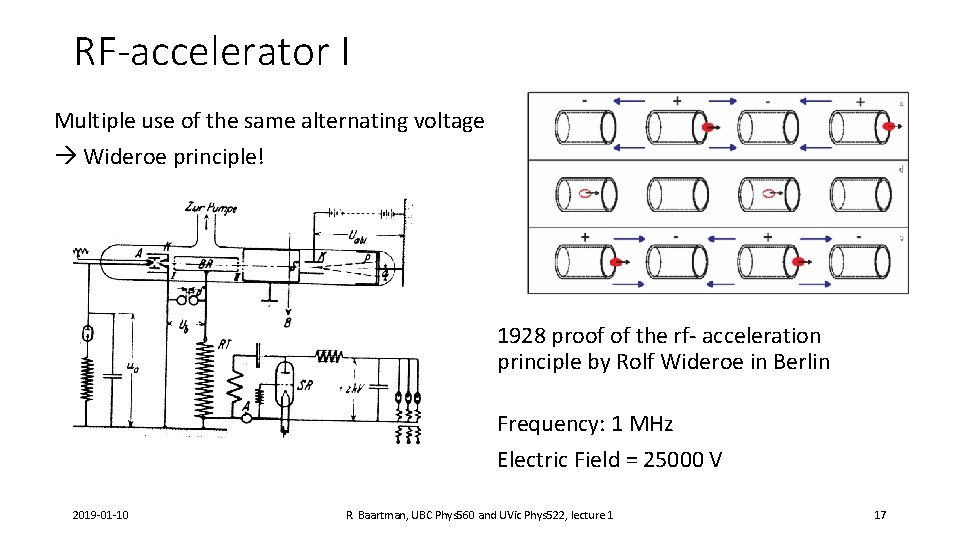

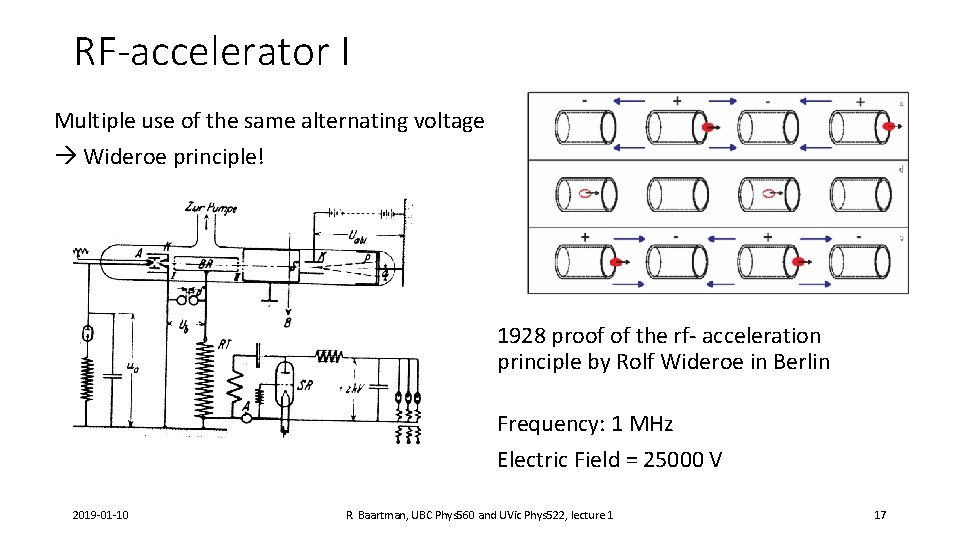

RF-accelerator I Multiple use of the same alternating voltage Wideroe principle! 1928 proof of the rf- acceleration principle by Rolf Wideroe in Berlin Frequency: 1 MHz Electric Field = 25000 V 2019 -01 -10 R. Baartman, UBC Phys 560 and UVic Phys 522, lecture 1 17

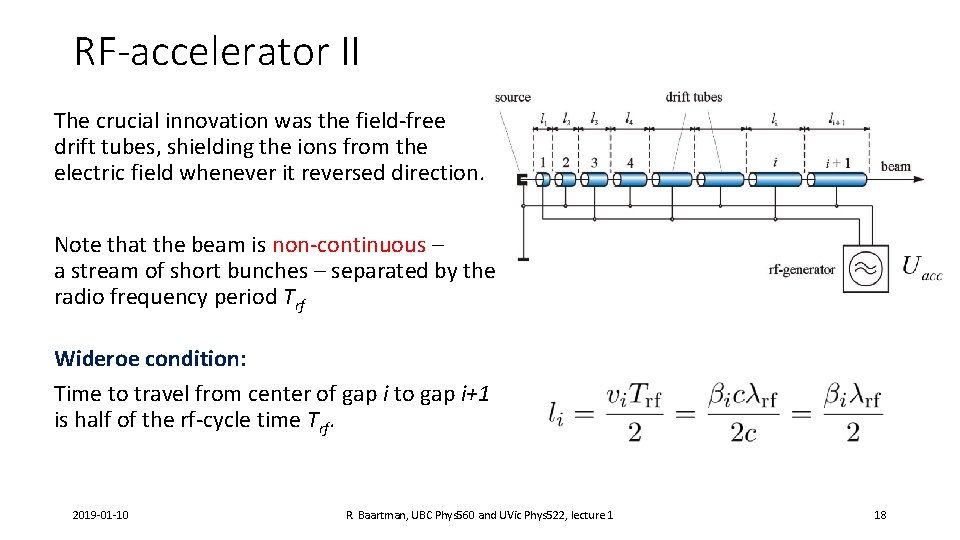

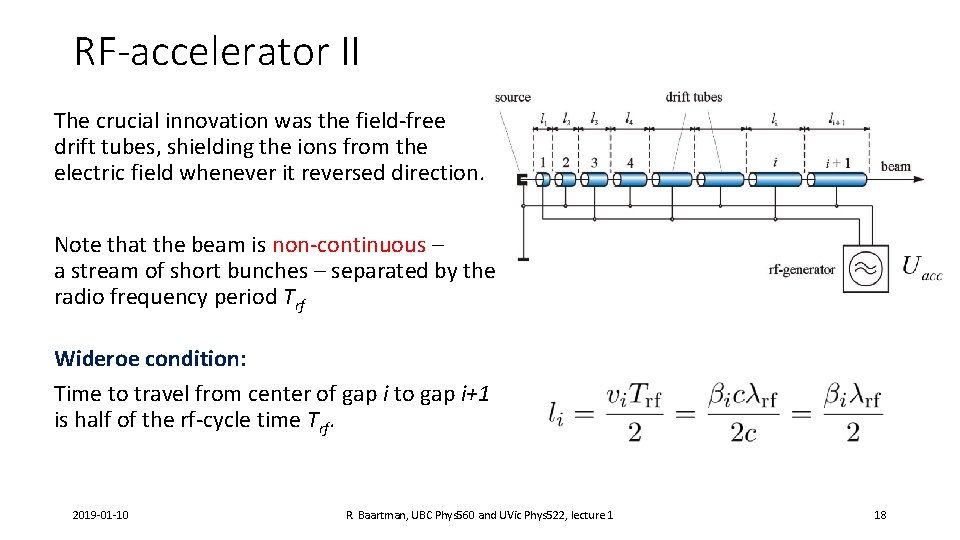

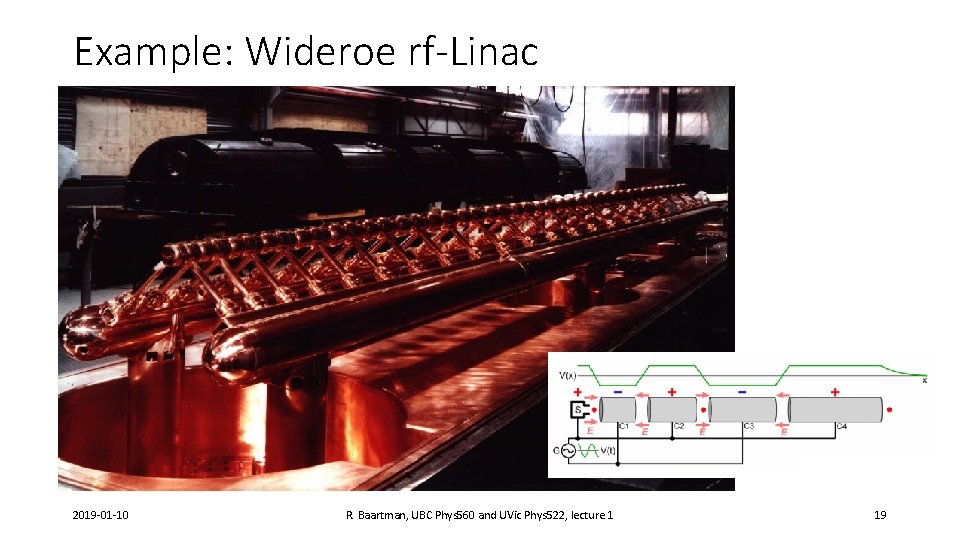

RF-accelerator II The crucial innovation was the field-free drift tubes, shielding the ions from the electric field whenever it reversed direction. Note that the beam is non-continuous – a stream of short bunches – separated by the radio frequency period Trf Wideroe condition: Time to travel from center of gap i to gap i+1 is half of the rf-cycle time Trf. 2019 -01 -10 R. Baartman, UBC Phys 560 and UVic Phys 522, lecture 1 18

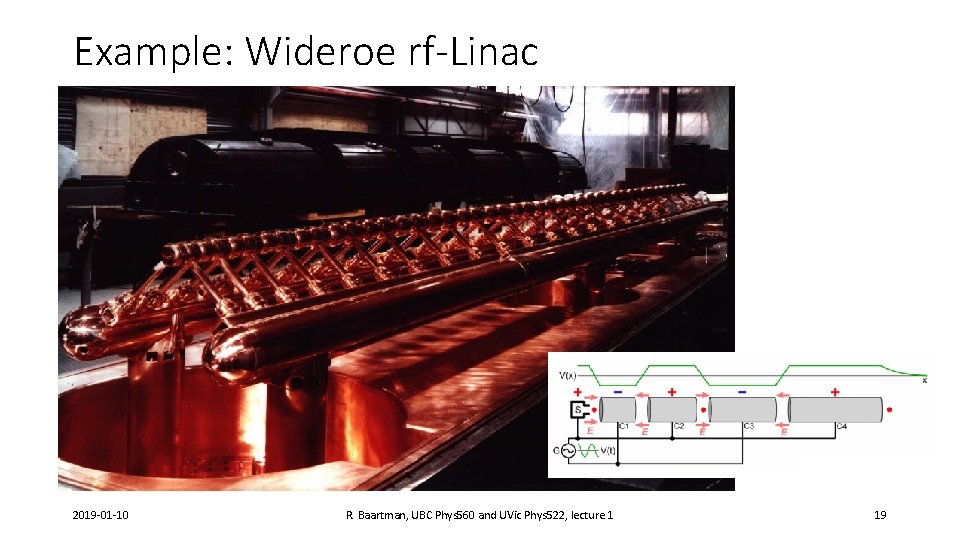

Example: Wideroe rf-Linac 2019 -01 -10 R. Baartman, UBC Phys 560 and UVic Phys 522, lecture 1 19

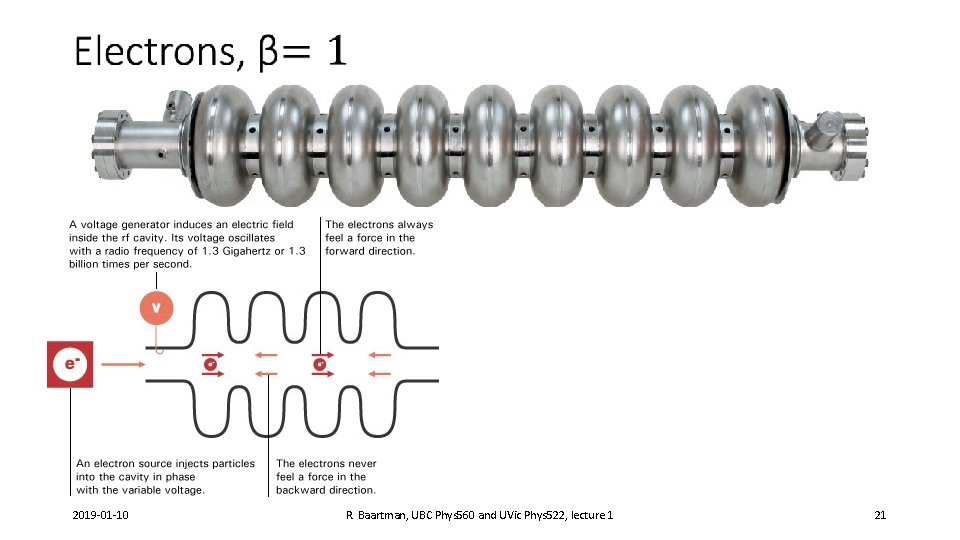

Linear accelerators: efficiency In linacs, each particle sees each RF gap only once. This is not efficient compared with circular machines. Ordinary copper cavities consume large amount of power to keep RF voltage in the >100 k. V range. Two solutions: 1. Pulse the beam (~60 Hz). Cavities only “on” for a duty factor of 1% or so. 2. Superconducting. Joule losses very small. 2019 -01 -10 R. Baartman, UBC Phys 560 and UVic Phys 522, lecture 1 20

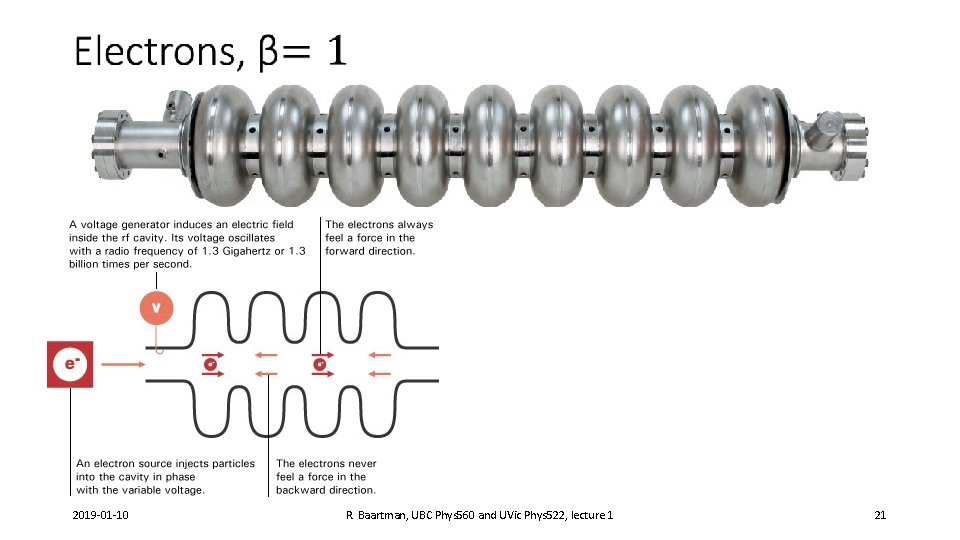

2019 -01 -10 R. Baartman, UBC Phys 560 and UVic Phys 522, lecture 1 21

Linear accelerator versus �� At low �� , the particle (bunch) periodicity ���� is short compared with the resonator size ��. But at �� =1, resonator size and bunch spacing are comparable. 2019 -01 -10 R. Baartman, UBC Phys 560 and UVic Phys 522, lecture 1 22

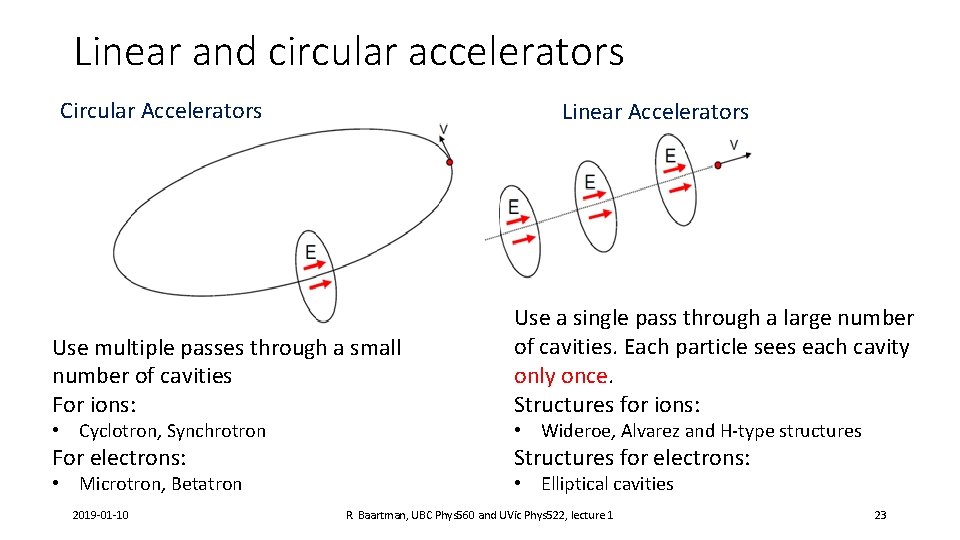

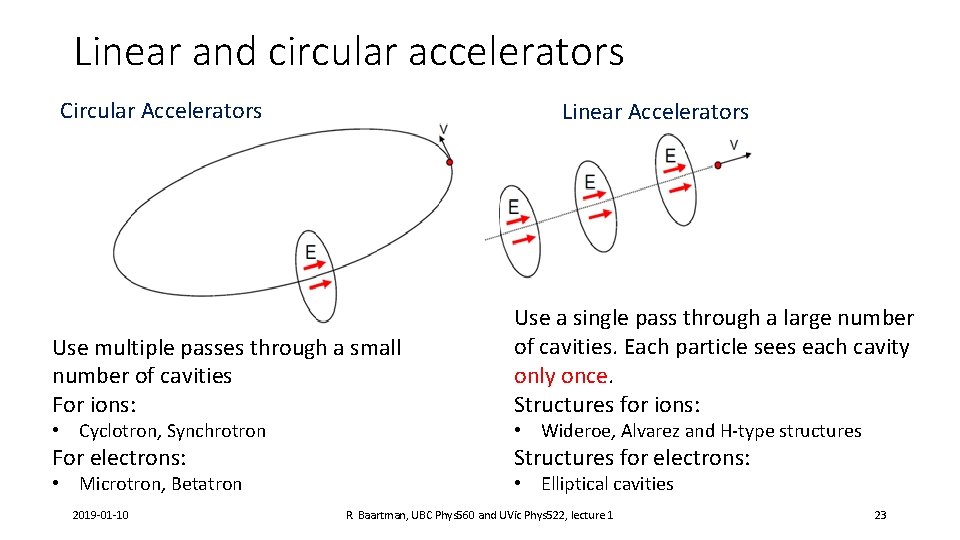

Linear and circular accelerators Circular Accelerators Linear Accelerators Use multiple passes through a small number of cavities For ions: Use a single pass through a large number of cavities. Each particle sees each cavity only once. Structures for ions: For electrons: Structures for electrons: • Cyclotron, Synchrotron • Microtron, Betatron 2019 -01 -10 • Wideroe, Alvarez and H-type structures • Elliptical cavities R. Baartman, UBC Phys 560 and UVic Phys 522, lecture 1 23

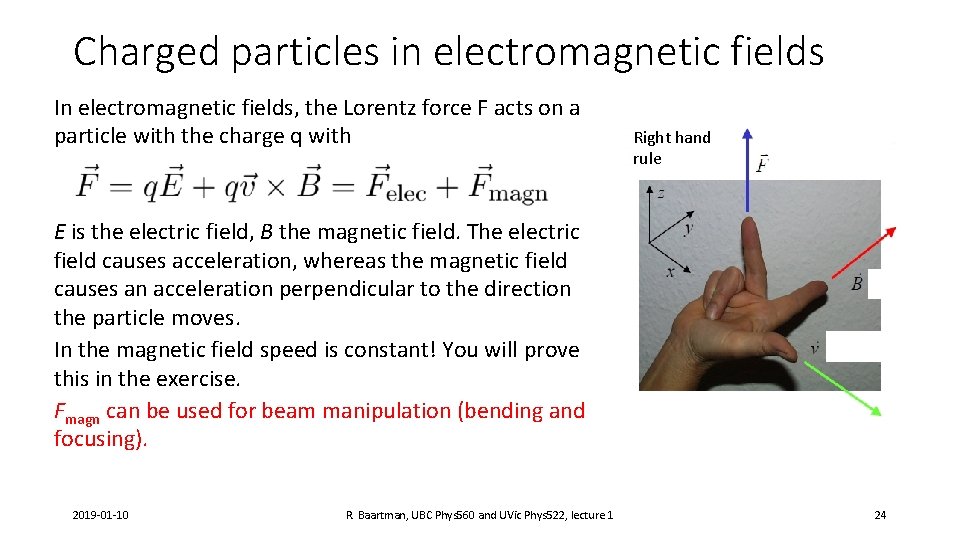

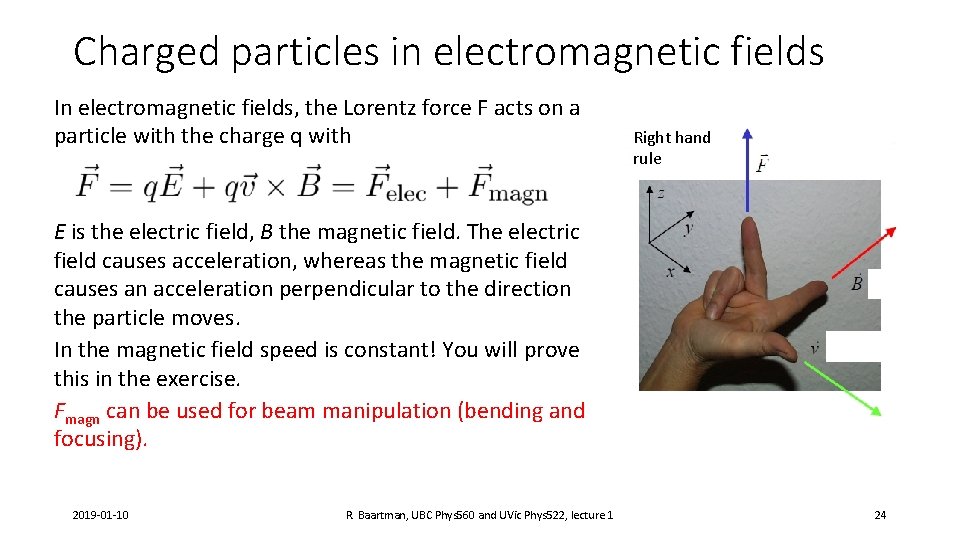

Charged particles in electromagnetic fields In electromagnetic fields, the Lorentz force F acts on a particle with the charge q with Right hand rule E is the electric field, B the magnetic field. The electric field causes acceleration, whereas the magnetic field causes an acceleration perpendicular to the direction the particle moves. In the magnetic field speed is constant! You will prove this in the exercise. Fmagn can be used for beam manipulation (bending and focusing). 2019 -01 -10 R. Baartman, UBC Phys 560 and UVic Phys 522, lecture 1 24

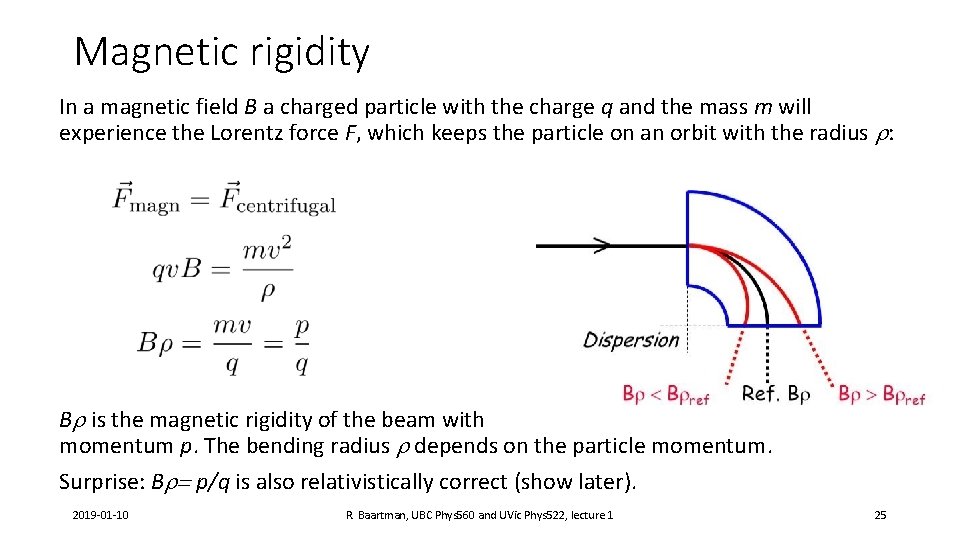

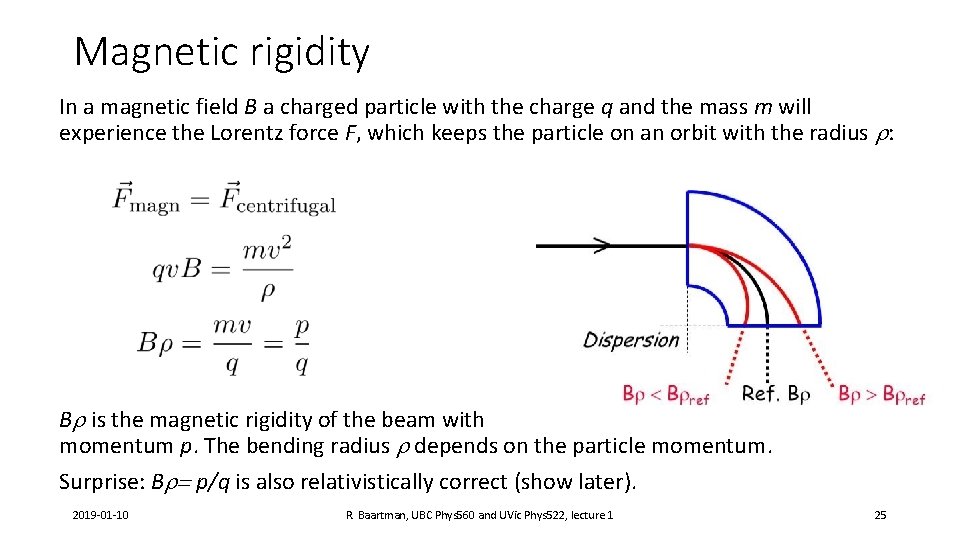

Magnetic rigidity In a magnetic field B a charged particle with the charge q and the mass m will experience the Lorentz force F, which keeps the particle on an orbit with the radius r: Br is the magnetic rigidity of the beam with momentum p. The bending radius r depends on the particle momentum. Surprise: Br= p/q is also relativistically correct (show later). 2019 -01 -10 R. Baartman, UBC Phys 560 and UVic Phys 522, lecture 1 25

Exercise 4. Prove that magnetic field does not affect charged particle speed. 5. For a (Ekin=) 500 Me. V proton, find the radius of curvature r in a magnetic field of 1 Tesla. Please do not use mass in kilograms, energy in joules or proton charge in coulombs; use electron charge as unit, and electron-volts as energy units. Rest mass of the proton is 938 Me. V/c 2. The exercise is meant to familiarize you with these “shortcut” methods of calculating particle dynamics. 2019 -01 -10 R. Baartman, UBC Phys 560 and UVic Phys 522, lecture 1 26