High Conservation Value HCV Review of national guidance

![Context: Oil palm expansion Area harvested [Mha] of oil palm fruit from 1961 to Context: Oil palm expansion Area harvested [Mha] of oil palm fruit from 1961 to](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h/ad7065746f533bb057c61034d110b354/image-22.jpg)

- Slides: 27

High Conservation Value (HCV): Review of national guidance Rachel Neugarten and Conrad Savy ICCB July 24 2013

Overview • What is High Conservation Value? • Review of HCV guidance from 20 countries • Recommendations

High Conservation Value Provides a framework for identifying, managing, and monitoring areas of critical importance or outstanding significance. conservation priority areas Private sector Site scale management

Six categories HCV 1. Areas containing globally, regionally or nationally significant concentrations of biodiversity values (e. g. endemism, endangered species, refugia). HCV 2. Globally, regionally or nationally significant large landscapelevel areas where viable populations of most if not all naturally occurring species exist in natural patterns of distribution and abundance. HCV 3. Areas that are in or contain rare, threatened or endangered ecosystems. HCV 4. Areas that provide basic ecosystem services in critical situations (e. g. watershed protection, erosion control). HCV 5. Areas fundamental to meeting basic needs of local communities (e. g. subsistence, health). HCV 6. Areas critical to local communities’ traditional cultural identity (areas of cultural, ecological, economic or religious significance identified in cooperation with such local communities). hcvnetwork. org

Applications • Forestry • Forest Stewardship Council (FSC) certification (Principle 9) • Agriculture – – Round-table for Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO) Round-Table on Responsible Soy (RTRS) Better Sugar Cane Initiative (BSI) Round-table for a Sustainable Cacao Economy (RSCE) • Biofuels – Roundtable on Sustainable Biofuels (RSB) – UK Renewable Transport Fuel Obligation – European Renewable Energy Source Directive • Finance • International Finance Corporation (IFC) Performance Standards • Conservation planning – National assessment in Gabon (ongoing) – Landscape-level assessments in Indonesia and Malaysia

Criticism “Terms are open to interpretation by the assessors, potentially leading to differences of opinion with dangerous consequences for biodiversity”

Global Guidance www. proforest. net, www. hcvnetwork. org (under review)

National Interpretations

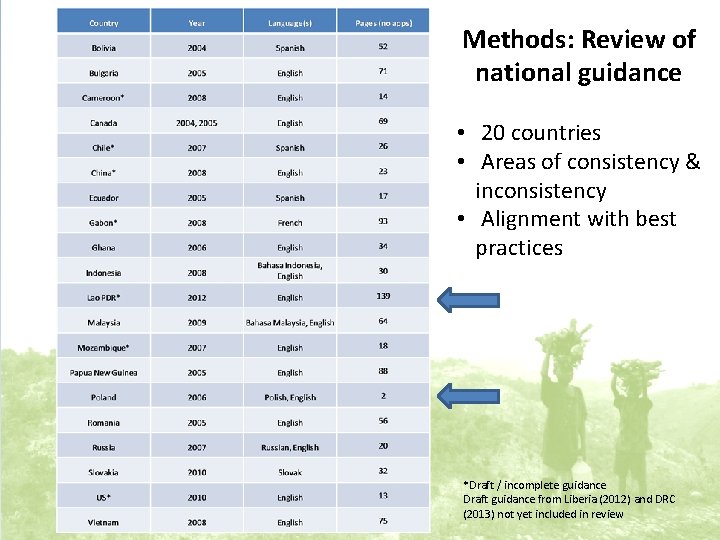

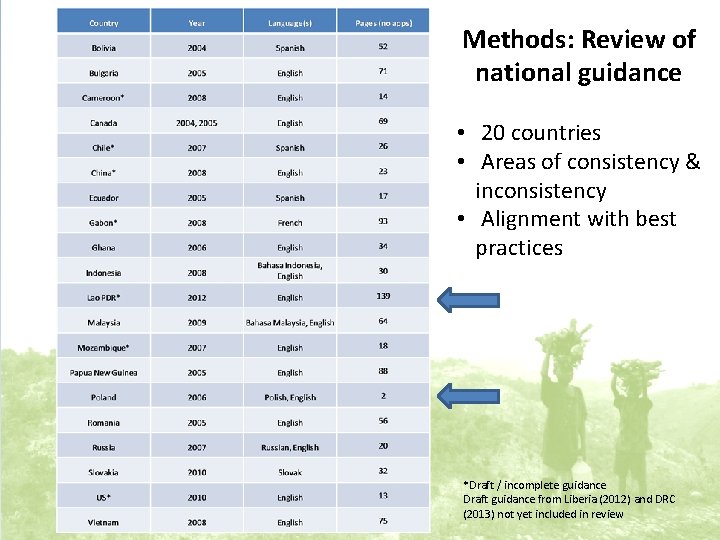

Methods: Review of national guidance • 20 countries • Areas of consistency & inconsistency • Alignment with best practices *Draft / incomplete guidance Draft guidance from Liberia (2012) and DRC (2013) not yet included in review

Results: Areas of consistency (n = 20) • • Need for stakeholder consultation (19 countries) International datasets / IUCN Red List (17) Precautionary approach (14) Assessing basic needs / cultural identity of local communities (HCV 5 and 6) (Indonesia, Malaysia, Vietnam)

Results: Inconsistencies • Definitions of terms – Species: IUCN CR, EN, or VU species, or none – Protected area types • Quantitative thresholds for identifying HCV – Minimum qualifying area for large intact ecosystems (10, 000 ha in Romania to 500, 000 ha in PNG) – Slope steepness (erosion control) (25 in Malaysia, 50 in Ecuador) • Management recommendations – Strict protection (Indonesia) vs. flexibility (Vietnam) – Riparian buffer widths (50 m in Papua New Guinea, 2 x width of the waterway in Ecuador)

Results: Best Practices 28 best practices, 6 categories: 1. Comprehensiveness 2. Practicality / ease of application 3. Adherence to recognized key principles 4. Adherence to established international standards 5. Links to adaptive management 6. Evidence cited

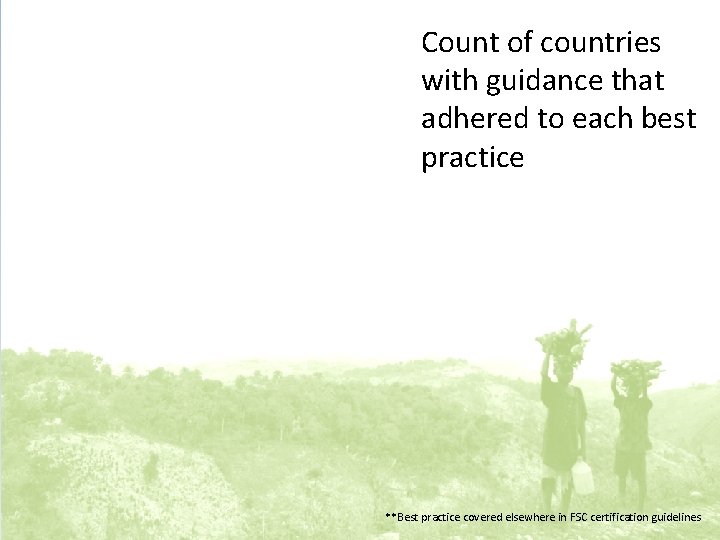

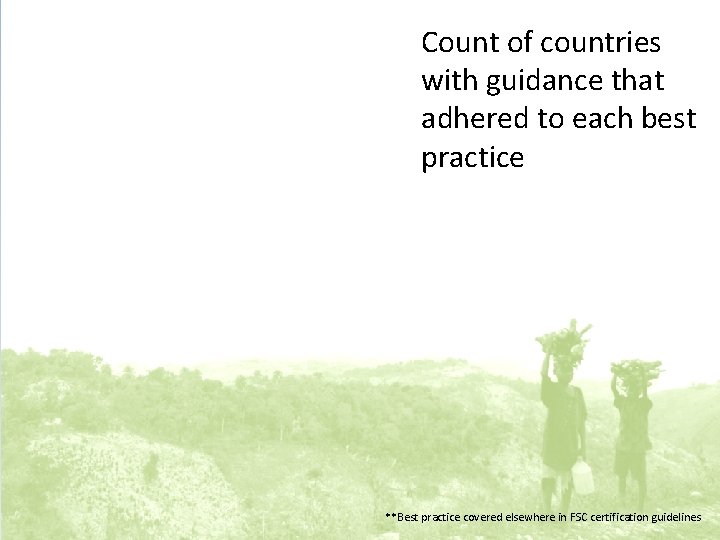

Count of countries with guidance that adhered to each best practice **Best practice covered elsewhere in FSC certification guidelines

Figure 1 summary • Guidance from most (≥ 17) countries: – Required stakeholder consultation (19) – Were comprehensive of all six categories of HCV (17) – Encouraged compliance with international standards (17) or national laws (17) – Included management recommendations (17) • Guidance from very few ( 4) countries: – Included detailed field survey methods (4) – Recommended peer review of HCV assessments (4) – Included recommendations for addressing overlapping or conflicting HCV areas (3)

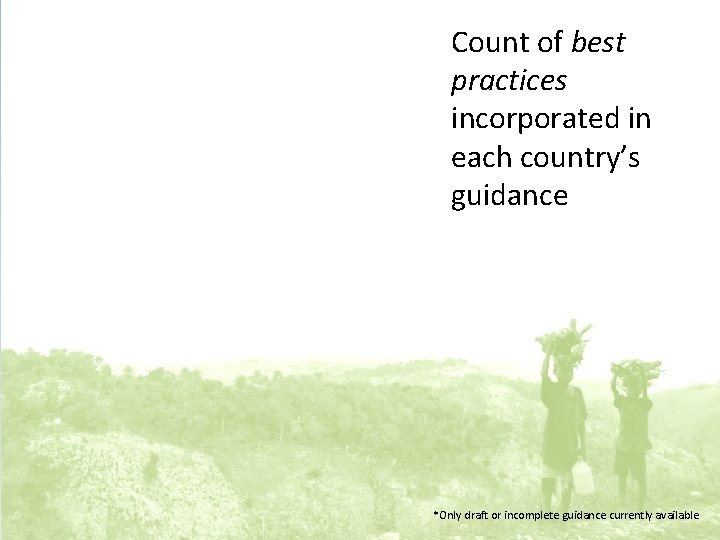

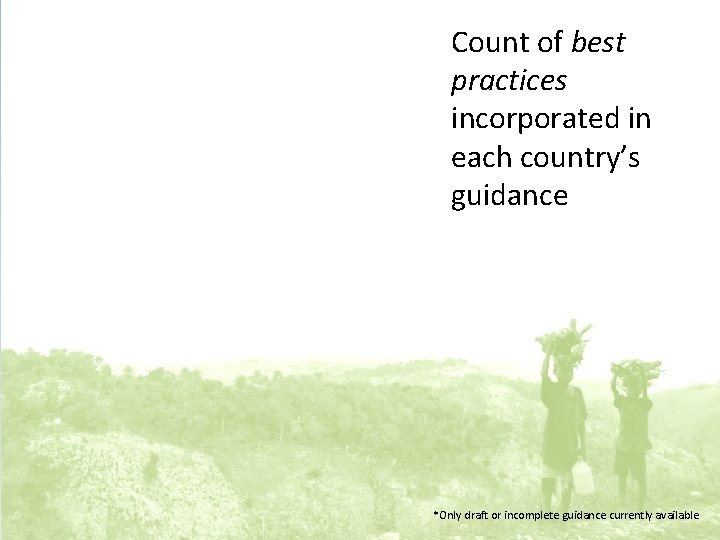

Count of best practices incorporated in each country’s guidance *Only draft or incomplete guidance currently available

Who cares? • Good standards are necessary to maintain conservation values • Commodities markets & finance sector are looking to international certification standards as global benchmark for sustainability • If standards are inconsistent, there is a risk of losing consumer trust in brands and certification schemes

Recommendations We recommend: 1. Establishing minimum global standards, while still leaving an appropriate level of flexibility (e. g. IUCN CR species always qualify as HCV) 2. Revisiting areas of inconsistency to ensure that differences are appropriate for the national context and not just a byproduct of diverse processes 3. Referring to existing tools such as the Integrated Biodiversity Assessment Tool (IBAT) 4. Requiring peer review of all HCV assessments to increase transparency, share good practice, and improve efficacy of commodity certification processes

http: //www. abcg. org/

Thank you rneugarten@conservation. org conradsavy@gmail. com Thanks to Conrad Savy, Natalie Bailey, Naamal De Silva, Tom Clark, Marcelo Levy, Tim Rayden, Christopher Stewart, Olive Tatio Sah, Chris Dickinson, Gary Paoli, Zhivko Bogdanov, and Madeleine Bottrill. Funding provided by USAID and ABCG

Extra slides

Urgency • Critical part of sustainable certification for major agricultural commodities • Make up a large and expanding portion of land use globally • Referenced in lending institution policies – IFC standards related to natural habitat; sustainable supply chains and commodities for agriculture and forestry • Influence an entire finance sector

![Context Oil palm expansion Area harvested Mha of oil palm fruit from 1961 to Context: Oil palm expansion Area harvested [Mha] of oil palm fruit from 1961 to](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h/ad7065746f533bb057c61034d110b354/image-22.jpg)

Context: Oil palm expansion Area harvested [Mha] of oil palm fruit from 1961 to 2009 (FAOSTAT 2011).

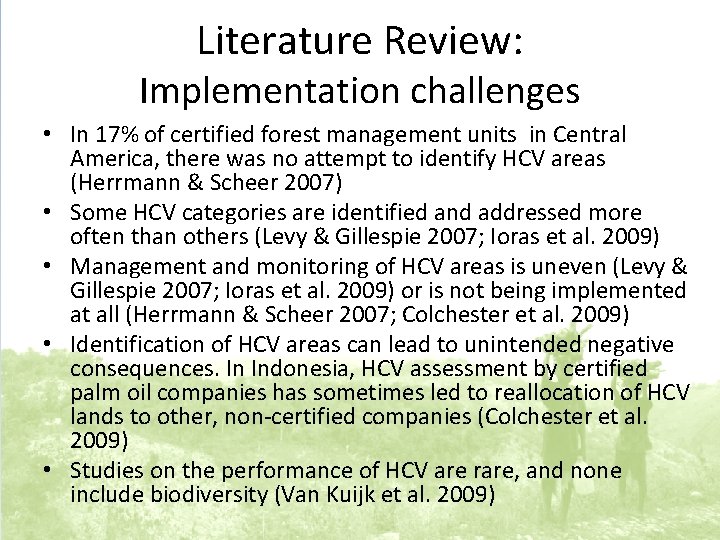

Literature Review: Implementation challenges • In 17% of certified forest management units in Central America, there was no attempt to identify HCV areas (Herrmann & Scheer 2007) • Some HCV categories are identified and addressed more often than others (Levy & Gillespie 2007; Ioras et al. 2009) • Management and monitoring of HCV areas is uneven (Levy & Gillespie 2007; Ioras et al. 2009) or is not being implemented at all (Herrmann & Scheer 2007; Colchester et al. 2009) • Identification of HCV areas can lead to unintended negative consequences. In Indonesia, HCV assessment by certified palm oil companies has sometimes led to reallocation of HCV lands to other, non-certified companies (Colchester et al. 2009) • Studies on the performance of HCV are rare, and none include biodiversity (Van Kuijk et al. 2009)

Recommendations from the literature • Developing more complete, consistent guidance • Building a repository of lessons learned from past HCV assessments (HCV Resource Network) • National- or landscape-scale HCV assessments – Landscape-level assessments have already been conducted in Indonesia and Malaysia and a national scale assessment is underway in Gabon • Greater commitment to appropriate long-term management of HCV areas by governments and industry association members

Implementation challenges Detailed legal review and a field study of situation in West Kalimantan, Indonesia Extensive HCV areas identified by RSPO member companies are not being protected but are being re-allocated by local government to other companies

Challenges (continued) “Some RSPO member companies have invested a considerable amount of resources, time and effort in identifying HCV areas. . . These delays have meant that companies have exceeded the permitted three-year period for preparing their areas prior to them securing their final leases. Overriding appeals by the companies, local government officials have chosen to terminate these permits and/or restrict the areas permitted to these companies and have re-allocated parts of these areas to other companies including non-RSPO members, some of which are allegedly clearing lands including HCV areas. ” “The study also found that RSPO member companies are choosing to relinquish substantial HCV areas… and are handing these HCV areas back to the government. They are doing this to avoid burdensome taxation, to reduce the size of the corresponding areas that they are obliged to develop as smallholdings and to make it easier to comply with the RSPO requirement that they manage HCV areas that are within their permits. However, HCV areas so released by the companies can be reallocated to other companies, who may not be RSPO members and who have no obligation to maintain or enhance HCVs. ”

HCV in Asia: the good news. • Most certification schemes lack enforcement mechanism, Indonesian Sustainable Palm Oil (ISPO) certification will be an exception; violators can be punished by law (Edwards and Laurance 2012) • Many SE Asian countries do not have guidelines for biodiversity considerations in logging concessions, but Cambodia, Indonesia, Laos, Malaysia and Vietnam do (Dennis et al. 2008) • International Tropical Timber Organization (ITTO) pioneered development of criteria & indicators; used as basis forest certification schemes and initial development of FSC principles and criteria in Indonesia and Malaysia (Dennis et al. 2008) • Three countries in SE Asia have FSC certified natural forests, two have certified plantations (Ibid. ) • Indonesia, Malaysia, and Myanmar have national certification schemes but they are not internationally recognized, don’t have much prestige on international markets (Ibid. ) • WWF Indonesia performed landscape-scale HCVF assessments for all of West Kalimantan province and for two regencies in Papua province (Ibid. ) • In Indonesia, the PT Sumalindo Lestari Jaya II has classified about 50, 000 hectares as HCVF (Karmann and Smith 2009)