Hierarchy of Evidence Randomized Controlled Trials RCT Module

- Slides: 22

Hierarchy of Evidence: Randomized Controlled Trials (RCT) Module 4 © American Academy of Neurology

Introduction • The RCT is perhaps the most powerful study design for addressing therapeutic questions • It is the methodological characteristics of the RCT that underlie its power – Randomization – Allocation Concealment – Blinding © American Academy of Neurology

Introduction, cont. • Other study characteristics – Well-defined clinical question / hypothesis – Well-defined study population – Appropriate control group – Adequate sample size & power – Minimal loss to follow-up – Appropriate analytic techniques © American Academy of Neurology

The Need for the RCT • Observational studies may mislead … – Increased risk of cancer, cardiovascular & cerebrovascular disease from HRT – Possible increased risk of hemorrhagic stroke from vitamin E – Increased risk of stroke from EC/IC bypass surgery – Lack of benefit of warfarin for IC stenosis – Harmful effects of minocycline in ALS © American Academy of Neurology

Clinical Equipoise • Provides the justification for an RCT • Represents collective uncertainty in the medical/scientific community regarding treatment efficacy • Relevant to selection of both active treatment and the control group © American Academy of Neurology

Randomization • Treatment assignment is left to the play of chance • Aims to control for both known and unknown confounding factors • Stratification, by contrast, can control only for known confounding factors • Hypothetical example, warfarin/aspirin for IC stenosis (warfarin group older than the younger group) © American Academy of Neurology

Blinding • Need to blind the subject, investigator assigning treatment and investigator evaluating outcome • Goal is to remove bias • Variety of approaches (identical-appearing placebo, more complex procedures e. g. INR in WASID) • Incomplete in surgical studies © American Academy of Neurology

Allocation Concealment • Difficult concept • Central to preserving effects of randomization • Easiest to understand via an example • Example - randomization schedule, but investigator knows the order of treatment assignments • Methods - opaque sealed envelopes, central pharmacy © American Academy of Neurology

Clinical Question / Hypothesis • RCT aims to address a specific clinical question • Need to specify primary outcome measure • Problem of multiple hypothesis testing • Primary outcome should be clinically meaningful • Clinical versus statistical significance © American Academy of Neurology

Study Population • Internal versus external validity • Homogeneity of the study population promotes internal validity and ability to demonstrate a treatment effect • Narrow inclusion/exclusion criteria limit generalization of study results • Is the study population representative of the patient in the clinic? © American Academy of Neurology

Sample Size • RCT should include discussion of sample size and power • Failure to demonstrate a treatment effect in an underpowered study may represent a type II (false negative) error • Demonstration of a treatment effect in an underpowered study may represent a type I (false positive) error • The value of confidence intervals © American Academy of Neurology

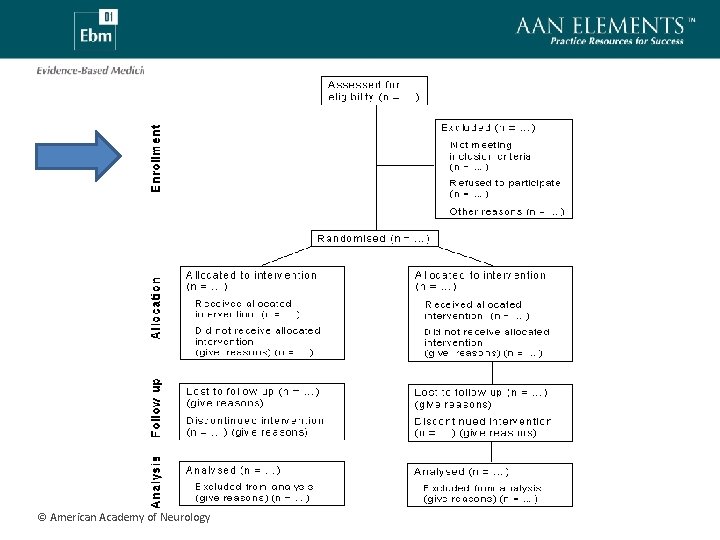

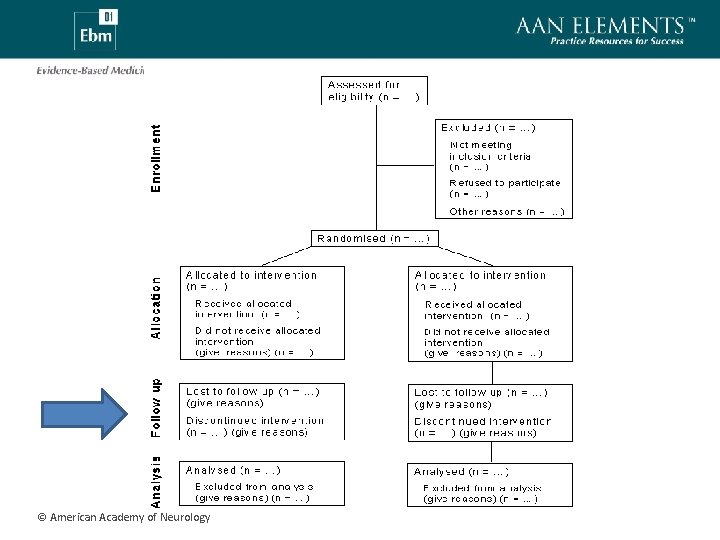

Loss to Follow-up • Important to know what happens to all subjects participating in an RCT • Excessive loss to follow-up may introduce selection bias • Strategies to handle missing data – Last observation carried forward – Sensitivity analysis © American Academy of Neurology

Cross-Overs • Subject randomized to treatment A, but receives treatment B • Cross-overs have the potential to undermine randomization • Avoid this problem using an intention-to-treat (ITT) analysis • ITT versus “as-treated” analyses © American Academy of Neurology

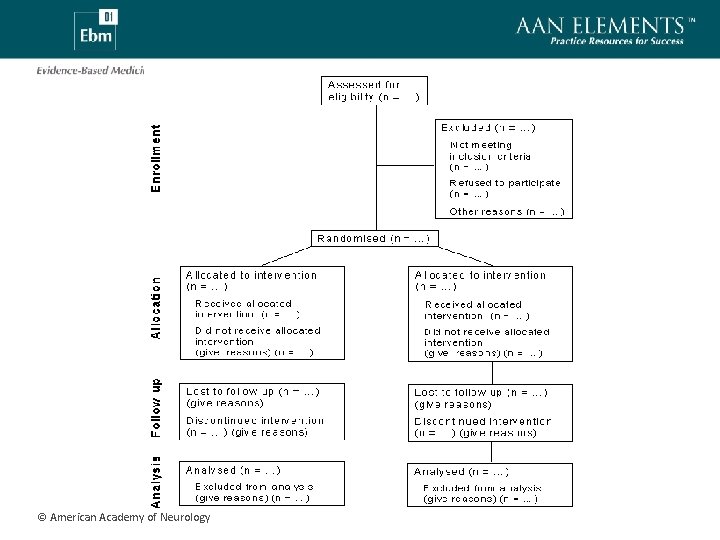

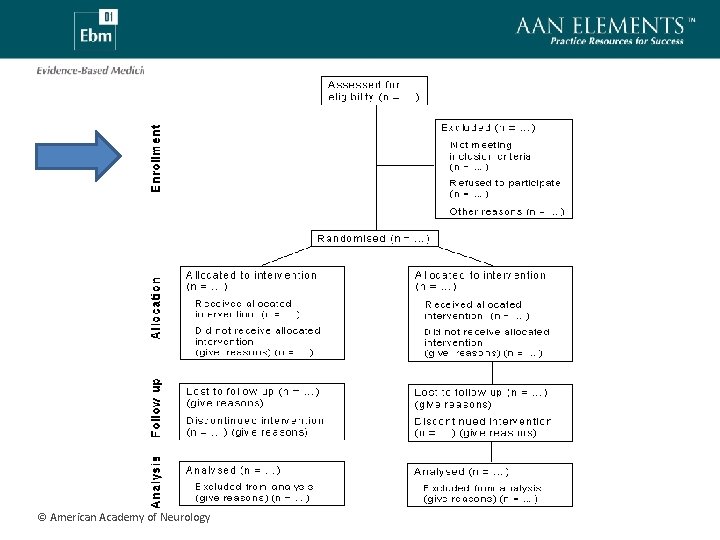

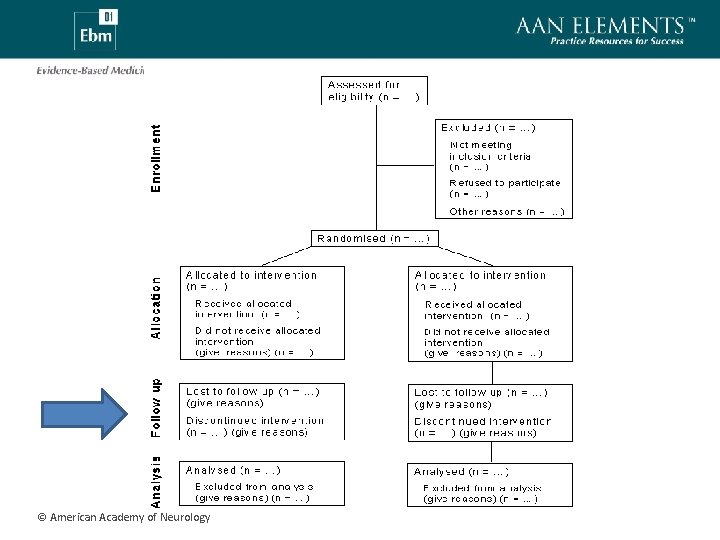

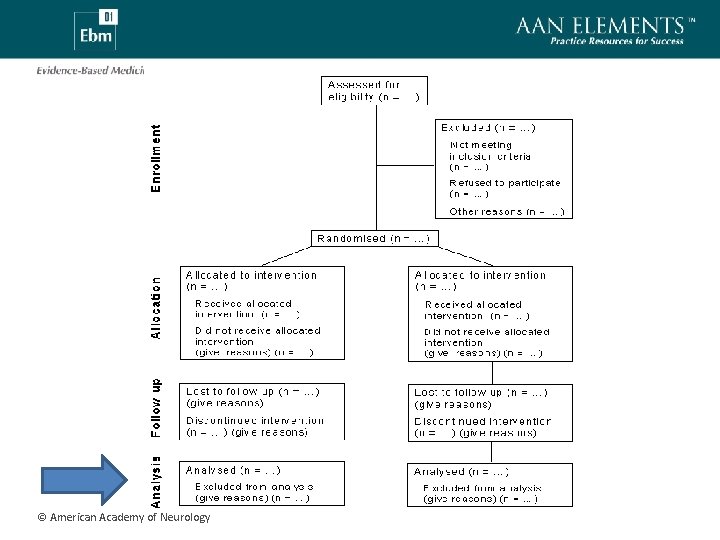

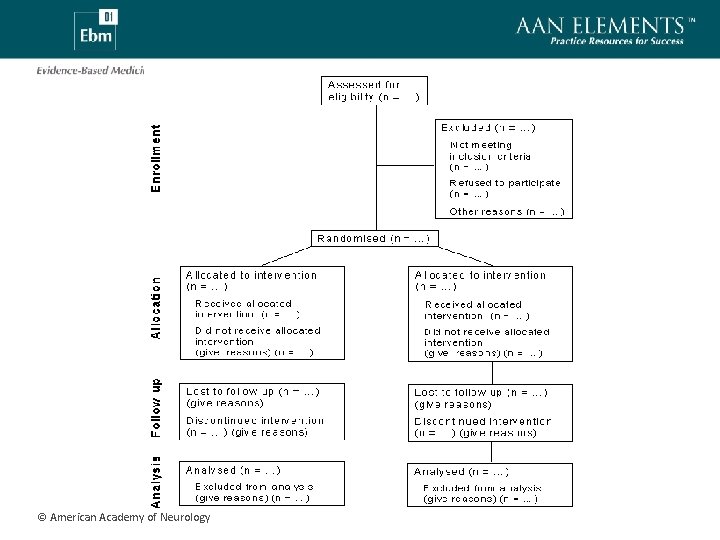

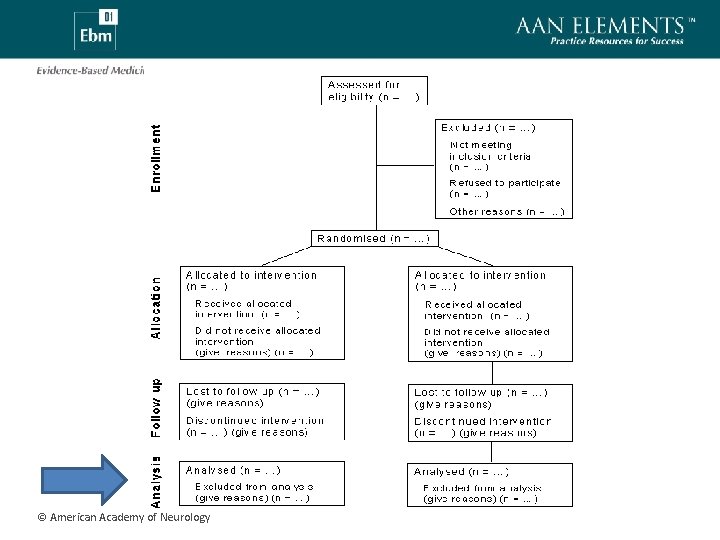

CONSORT • CONsolidated Standards Of Reporting Trials (http: //www. consort-statement. org/index. aspx? o=1077 ) • Consensus document regarding reporting results of RCT • 22 item check-list • Includes flow-diagram for explicating study participant flow © American Academy of Neurology

© American Academy of Neurology

© American Academy of Neurology

© American Academy of Neurology

© American Academy of Neurology

© American Academy of Neurology

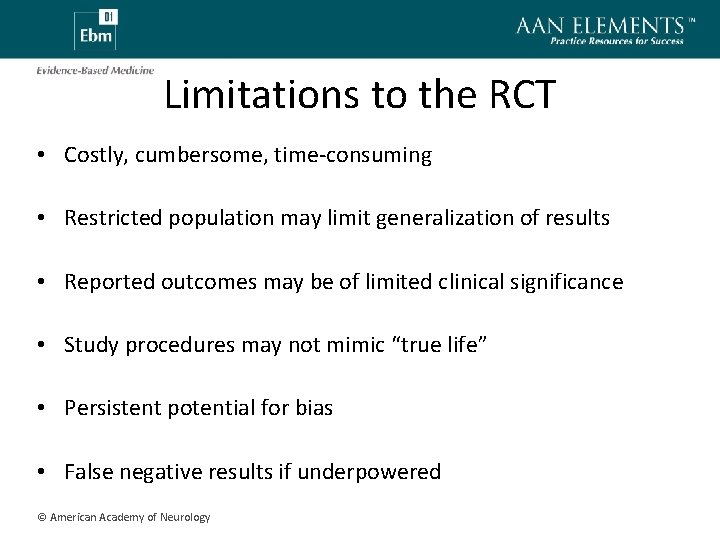

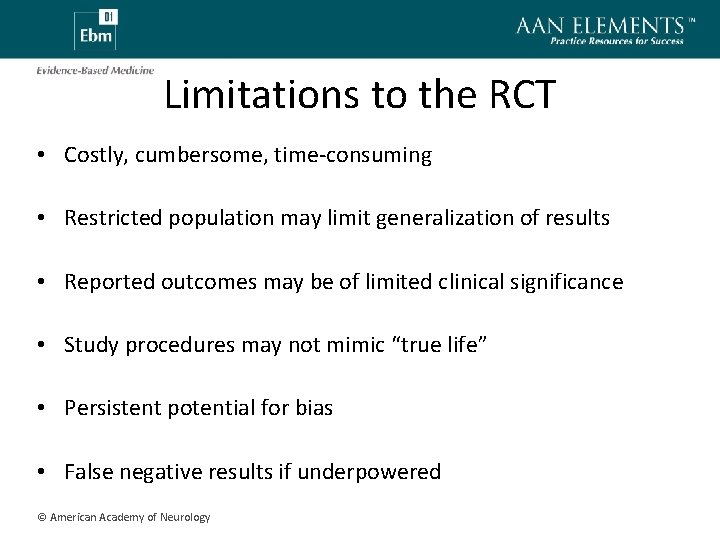

Limitations to the RCT • Costly, cumbersome, time-consuming • Restricted population may limit generalization of results • Reported outcomes may be of limited clinical significance • Study procedures may not mimic “true life” • Persistent potential for bias • False negative results if underpowered © American Academy of Neurology

References • • • Risks and benefits of estrogen plus progestin in healthy postmenopausal women: principal results from the Women’s Health Initiative Randomized Controlled Trial. JAMA 2002 288: 321 -333 Cardiovascular disease outcomes during 6. 8 years of hormone therapy: Heart and Estrogen/progestin Replacement Study follow-up (HERS II). JAMA 2002 288: 49 -57 Pravastatin in elderly individuals at risk of vascular disease (PROSPER): a randomized controlled trial. Lancet 2002 360: 162301630 Vitamin E in the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease and cancer: the Women’s Health Study: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2005 294: 56 -65 Effects of long-term vitamin E supplementation on cardiovascular events and cancer: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2005 293: 1338 -1347 © American Academy of Neurology

References • • • Comparison of warfarin and aspirin for symptomatic intracranial arterial stenosis. NEJM 2005 352: 1305 -1316 The Warfarin-Aspirin Symptomatic Intracranial Disease Study. Neurology 1995 45: 1488 -1493 Efficacy of minocycline in patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: a phase III randomized trial. Lancet Neurol 2007 6: 1045 -1053 Higgins JPT, Green S (Editors). Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions 4. 2. 5 (updated May 2005). In The Cochrane Library, Issue 3, 2005, Chichester, UK. John Wiley & Sons Ltd (http: //www. cochrane. dk/cochrane/handbook/hbook. htm) Tissue plasminogen activator for acute ischemic stroke, NEJM 1995 333: 1581 -1587 © 1995 Massachusetts Medical Society. All Rights Reserved. © American Academy of Neurology