Hemoglobin Structure Function Objectives of the Lecture 1

Hemoglobin Structure & Function

Objectives of the Lecture 1 - Understanding the main structural & functional details of hemoglobin as one of the hemoproteins. 2 - Identify types & relative concentrations of normal adult hemoglobin with reference to HBA 1 c with its clinical application. 3 - Recognize some of the main genetic & biochemical aspects of methemoglobinopathies with some implications on clinical features (with focusing on thalassemias). thalassemias

Hemoglobin is a globular hemoprotein • Hemeproteins are a group of specialized proteins that contain heme as a tightly bound prosthetic group. • Heme is a complex of protoporphyrin IX & ferrous iron (Fe 2+). • The iron is held in the center of the heme molecule by bonds to the four nitrogens of the porphyrin ring. • The heme Fe 2+ can form two additional bonds, one on each side of the planar porphyrin ring. One of these positions is coordinated to the side chain of a histidine amino acid of the globin molecule, whereas the other position is available to bind oxygen

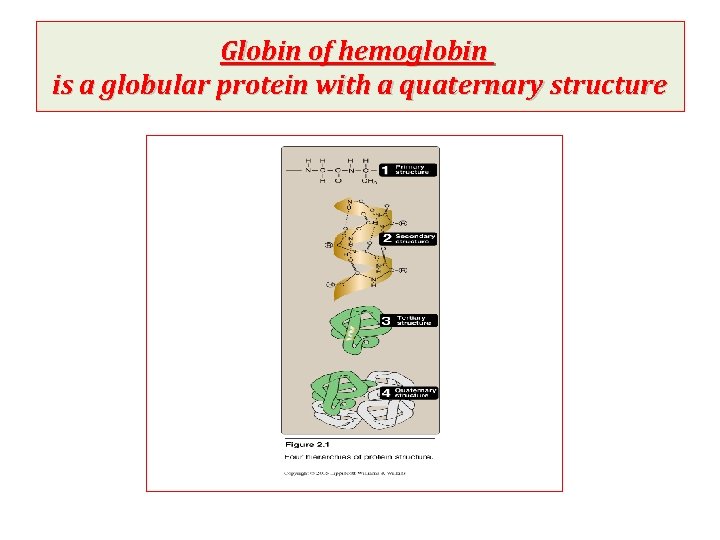

Globin of hemoglobin is a globular protein with a quaternary structure

Structure of heme Heme is a complex of protoporphyrin IX and ferrous iron (Fe 2+). The iron is held in the center of the heme molecule by bonds of the four nitrogens of the protoporphrin ring. Heme F 2+ can form two additional bonds, one on each side of the porphyrin ring. One of these positions is coordinated to the side chain of histidine amino acid of the globin molecule, whereas the other position is available to bind oxygen

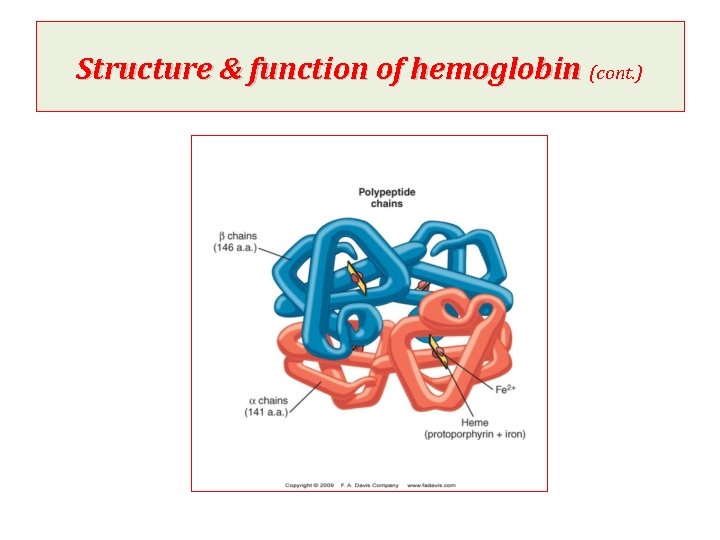

Structure & function of hemoglobin • Hemoglobin is found exclusively in RBCs • Its main function is to transport oxygen from lungs to the tissues & carbon dioxide & hydrogen protons from tissues to lungs. • Hemoglobin A is the major hemoglobin in adults, is composed of four polypeptide chains, 2 alpha (a) & 2 beta (b) chains, held together by noncovalent interactions • Each day, 6 -7 grams of hemoglobin is synthesized to replace lost through normal turn over of RBCs. • Each subunit has stretches of a-helical structure & a heme binding pocket.

Structure & function of hemoglobin (cont. )

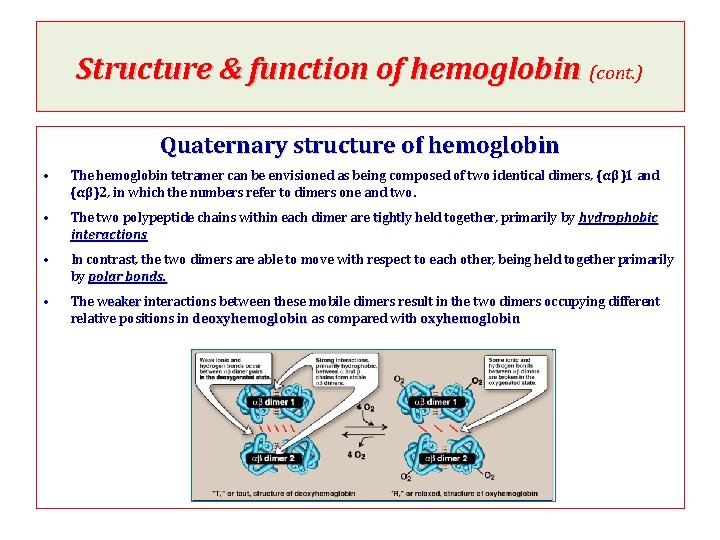

Structure & function of hemoglobin (cont. ) Quaternary structure of hemoglobin • The hemoglobin tetramer can be envisioned as being composed of two identical dimers, (αβ)1 and (αβ)2, in which the numbers refer to dimers one and two. • The two polypeptide chains within each dimer are tightly held together, primarily by hydrophobic interactions • In contrast, the two dimers are able to move with respect to each other, being held together primarily by polar bonds. • The weaker interactions between these mobile dimers result in the two dimers occupying different relative positions in deoxyhemoglobin as compared with oxyhemoglobin

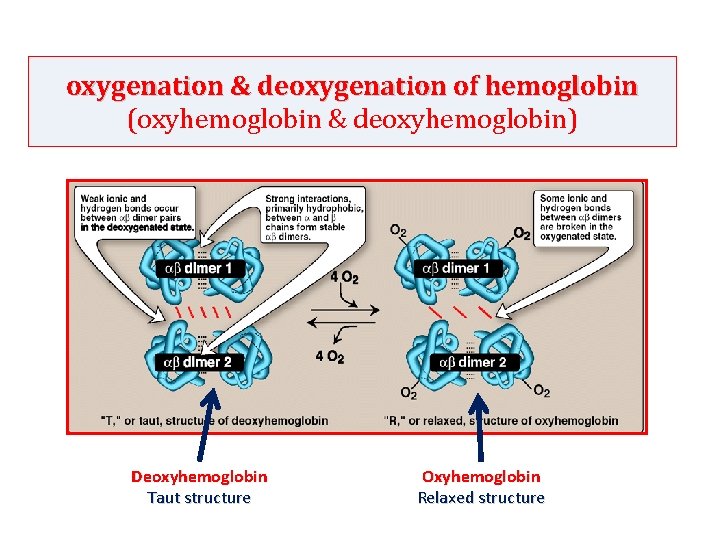

oxygenation & deoxygenation of hemoglobin (oxyhemoglobin & deoxyhemoglobin) Deoxyhemoglobin Taut structure Oxyhemoglobin Relaxed structure

Types of adult hemoglobin 3– 6 % HBA: the major hemoglobin in humans HBA 2: first appears 12 weeks after birth- a minor component of normal adult HB HBF: normally synthesized only during fetal development HBA 1 C : has glucose residues attached to b-globin chains – increased amounts in DM

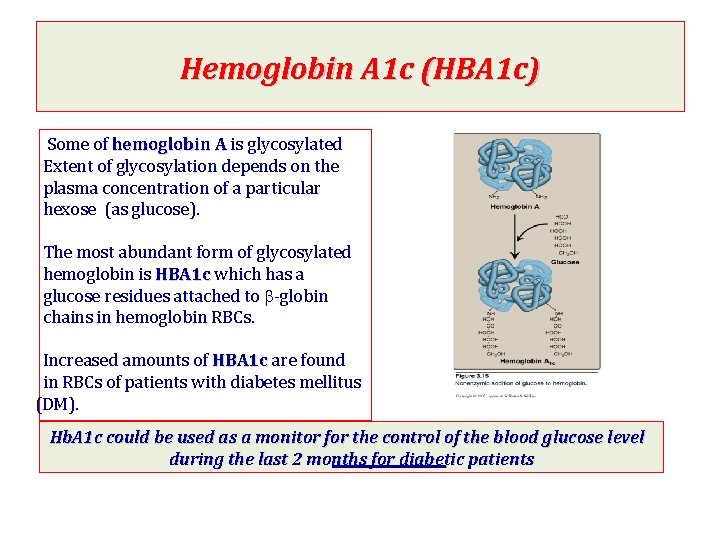

Hemoglobin A 1 c (HBA 1 c) Some of hemoglobin A is glycosylated Extent of glycosylation depends on the plasma concentration of a particular hexose (as glucose). The most abundant form of glycosylated hemoglobin is HBA 1 c which has a glucose residues attached to b-globin chains in hemoglobin RBCs. Increased amounts of HBA 1 c are found in RBCs of patients with diabetes mellitus (DM). Hb. A 1 c could be used as a monitor for the control of the blood glucose level during the last 2 months for diabetic patients

Hemoglobinopathies are members of a family of genetic disorders caused by: 1 - Production of a structurally abnormal hemoglobin molecule (Qualitative hemoglobinopathies) hemoglobinopathies Or: 2 - Synthesis of insufficient quantities of normal hemoglobin (Quantitative hemoglobinopathies) hemoglobinopathies Or: 3 - both (rare)

Thalassemias • Thalassemias are hereditary hemolytic diseases in which an imbalance occurs in the synthesis of globin chains. • They are most common single gene disorders in humans. • Normally, Normally synthesis of a- and b- globin chains are coordinated, so that each a-globin chain has a b-globin chain partner. This leads to the formation of a 2 b 2 (Hb. A). • In thalassemias, thalassemias the synthesis of either the a- or b-globin chain is defective.

Thalassemias (cont. ) Thalassemia can be caused by a variety of mutations, including: 1 - Entire gene deletions (whole gene is absent) absent Or: 2 - Substitutions or deletions of one or more nucleotides in the DNA. Each thalassemia can be classified as either: either 1 - A disorder in which no globin chains are produced (ao- or bo -thalassemia) Or: 2 - Some b-chains are synthesized, but at a reduced rate (a+- or b+- thalassemia).

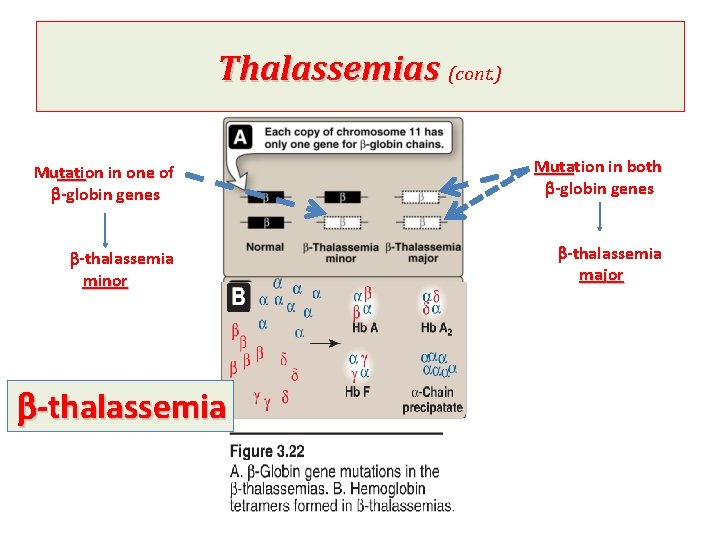

Thalassemias (cont. ) 1 - b-thalassemias: § Synthesis of b-globin chains are decreased or absent, absent whereas a-globin synthesis is normal. § a-globin chains cannot form stable tetramers & therefore precipitate causing premature death of RBCs ending in chronic hemolytic anemia § Also, a 2 g 2 (Hb. F) & a 2 d 2 (Hb. A 2 ) are accumulated.

Thalassemias (cont. ) There are only two copies of the b -globin gene in each cell (one on each chromosome 11). So, individuals with b -globin gene defects have either: 1 - b-thalassemia minor (b -thalassemia trait): if they have only one defective b-globin gene. 2 - b- thalassemia major (Colley anemia): if both genes are defective.

Thalassemias (cont. ) Mutation in one of b-globin genes Mutation in both b-globin genes b-thalassemia minor b-thalassemia major b-thalassemia

Thalassemias (cont. ) Some clinical aspects of b-thamassemias: 1 - As b-globin gene is not expressed until late fetal gestation, the physical manifestations of b -thalassemias appear only after birth 2 - Individuals with b -thalassemias minor, minor make some b-chains, and usually require no specific treatment. 3 - Infants born with b - thalassemias major seem healthy at birth, birth but become severely anemic during the first or second years of life They require regular transfusions of blood.

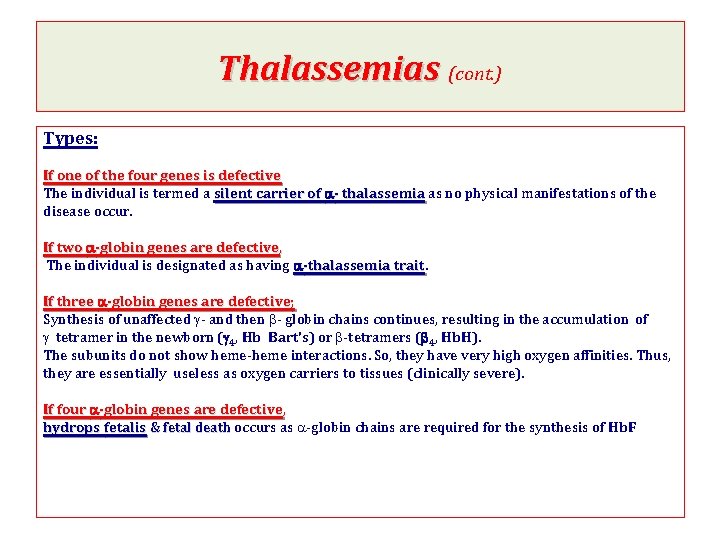

Thalassemias (cont. ) 2 - a-thalassemia: Synthesis of a-globin chains is decreased or absent Each individual's genome contains four copies of the a-globin (two on each chromosome 16), there are several levels of a-globin chain deficiencies

Thalassemias (cont. ) Types: If one of the four genes is defective The individual is termed a silent carrier of a- thalassemia as no physical manifestations of the disease occur. If two a-globin genes are defective, The individual is designated as having a-thalassemia trait If three a-globin genes are defective; Synthesis of unaffected g- and then b- globin chains continues, resulting in the accumulation of g tetramer in the newborn (g 4, Hb Bart's) or b-tetramers (b 4, Hb. H). The subunits do not show heme-heme interactions. So, they have very high oxygen affinities. Thus, they are essentially useless as oxygen carriers to tissues (clinically severe). If four a-globin genes are defective, hydrops fetalis & fetal death occurs as a-globin chains are required for the synthesis of Hb. F

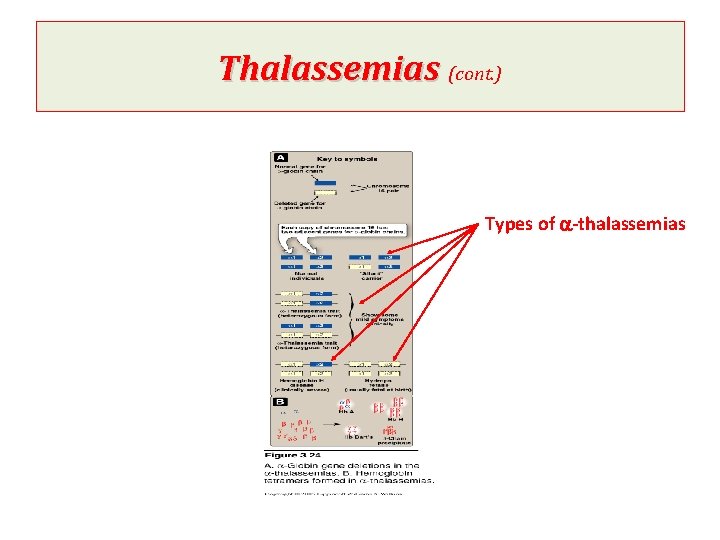

Thalassemias (cont. ) Types of a-thalassemias

Sickle cell anemia Definition: Sickle cell anemia is a genetic disorder of the blood caused by a single nucleotide alteration (a point mutation) in the b-globin gene. Inheritance of sickle cell anemia: Sickle cell disease is a homozygous recessive disorder: i. e. It occurs in individuals who have inherited two mutant genes (one from each parent) that code for synthesis of the b chains of the globin molecule. RBCs of homozygous is totally HB S (a 2 bs 2 ) Heterozygotes individuals: Have one normal and one sickle cell gene RBCs of heterozygotes contain both HB S (a 2 bs 2 ) & HB A (a 2 b 2 ) These individuals have sickle cell trait

Clinical manifestations of sickle cell anemia Homozygous individuals An infant (first 2 years of life) begins show manifestations when sufficient Hb. F is replaced by Hb. S Clinical manifestations: - Chronic hemolytic anemia - Lifelong episodes of pain - Increased susceptibility to infection - Acute chest syndrome - Stroke - Splenic & renal dysfunction - Bone changes due to bone marrow hyperplasia Heterozygote individuals Usually do not show clinical symptoms

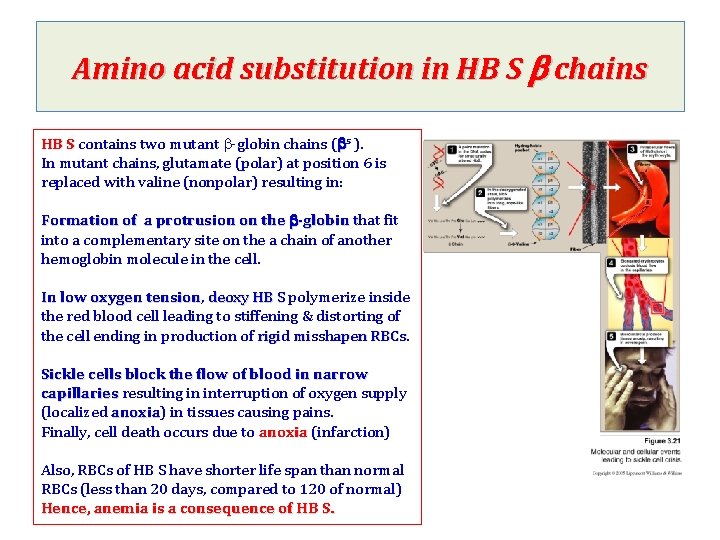

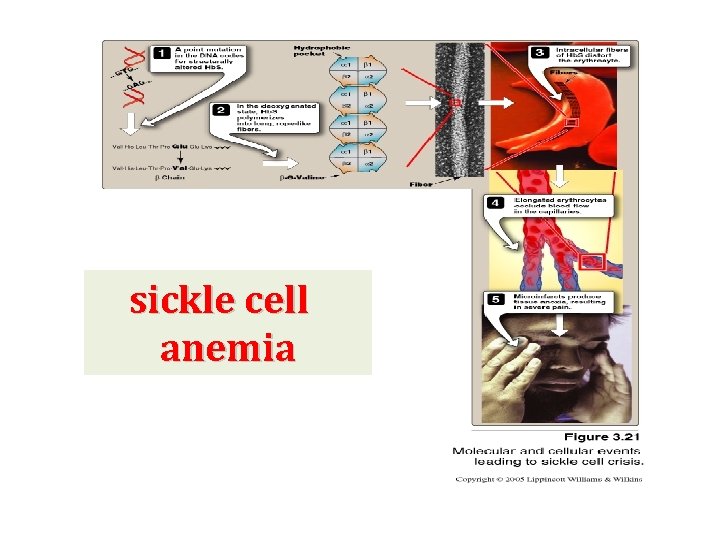

Amino acid substitution in HB S b chains HB S contains two mutant b-globin chains (bs ). In mutant chains, glutamate (polar) at position 6 is replaced with valine (nonpolar) resulting in: Formation of a protrusion on the b-globin that fit into a complementary site on the a chain of another hemoglobin molecule in the cell. In low oxygen tension, tension deoxy HB S polymerize inside the red blood cell leading to stiffening & distorting of the cell ending in production of rigid misshapen RBCs Sickle cells block the flow of blood in narrow capillaries resulting in interruption of oxygen supply (localized anoxia) anoxia in tissues causing pains. Finally, cell death occurs due to anoxia (infarction) Also, RBCs of HB S have shorter life span than normal RBCs (less than 20 days, compared to 120 of normal) Hence, anemia is a consequence of HB S.

sickle cell anemia

Factors that increase sickling The extent of sickling is increased by any factor that increases the proportion of HB S in the deoxy state as in cases of 1 - Decreased oxygen tension: in high altitudes flying in a nonpressurized plane 2 - Increased p. CO 2 3 - Decrease p. H 4 - Increased 2, 3 - BPG in RBCs

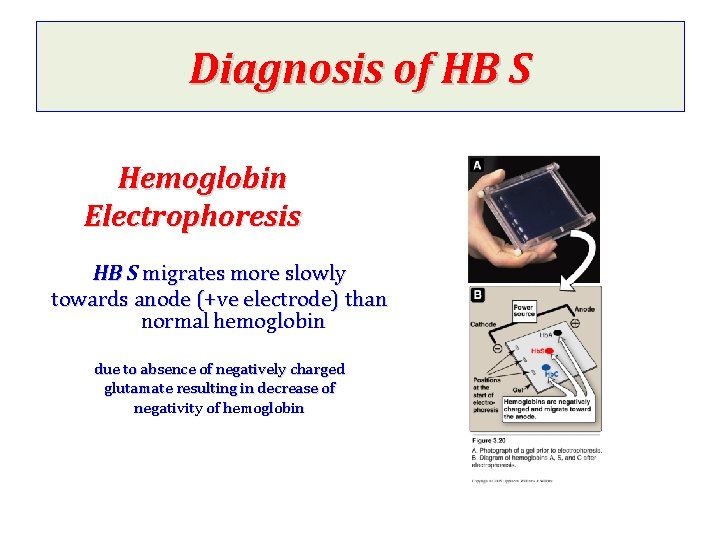

Diagnosis of HB S Hemoglobin Electrophoresis HB S migrates more slowly towards anode (+ve electrode) than normal hemoglobin due to absence of negatively charged glutamate resulting in decrease of negativity of hemoglobin

Selective advantage of the heterozygote state Heterozygotes individuals for sickle cell anemia are less suscibtiple to malaria caused by the parasite Plasmodium falciparum as their RBCs have shorter lifespan than normal , the parasite cannot complete its natural stage of development in RBCs. HB S gene is highly frequent in Africa in which malaria is also highly frequent.

Methemoglobinemia • • • Methemoglobin results from oxidation of the ferrous ion (Fe 2+) of heme of hemoglobin to ferric (Fe 3+) ion Methemoglobinemia is characterized by “chocolate cyanosis” i. e. brown-blue coloration of skin & membranes & chocolate colored blood Causes of oxidation of ferrous ions: 1 - Drugs as nitrates 2 - Endogenous products (as reactive oxygen species ) 3 - Inherited defects (as in certain mutations of a or b chains) 4 - Deficiency of NADH-Met HB reductase : enzyme for reduction of Fe 3+ of Met HB • RBCs of newborns have ½ capacity of adults to reduce Met HB & therefore they are more susceptible to Met HB formation by previous factors. • • Clinically, Clinically symptoms are due to tissue hypoxia Treatment: Treatment Methylene blue (to reduce the ferric ions)

- Slides: 29