Helping Student Veterans Persist to Graduation Dr Mari

- Slides: 1

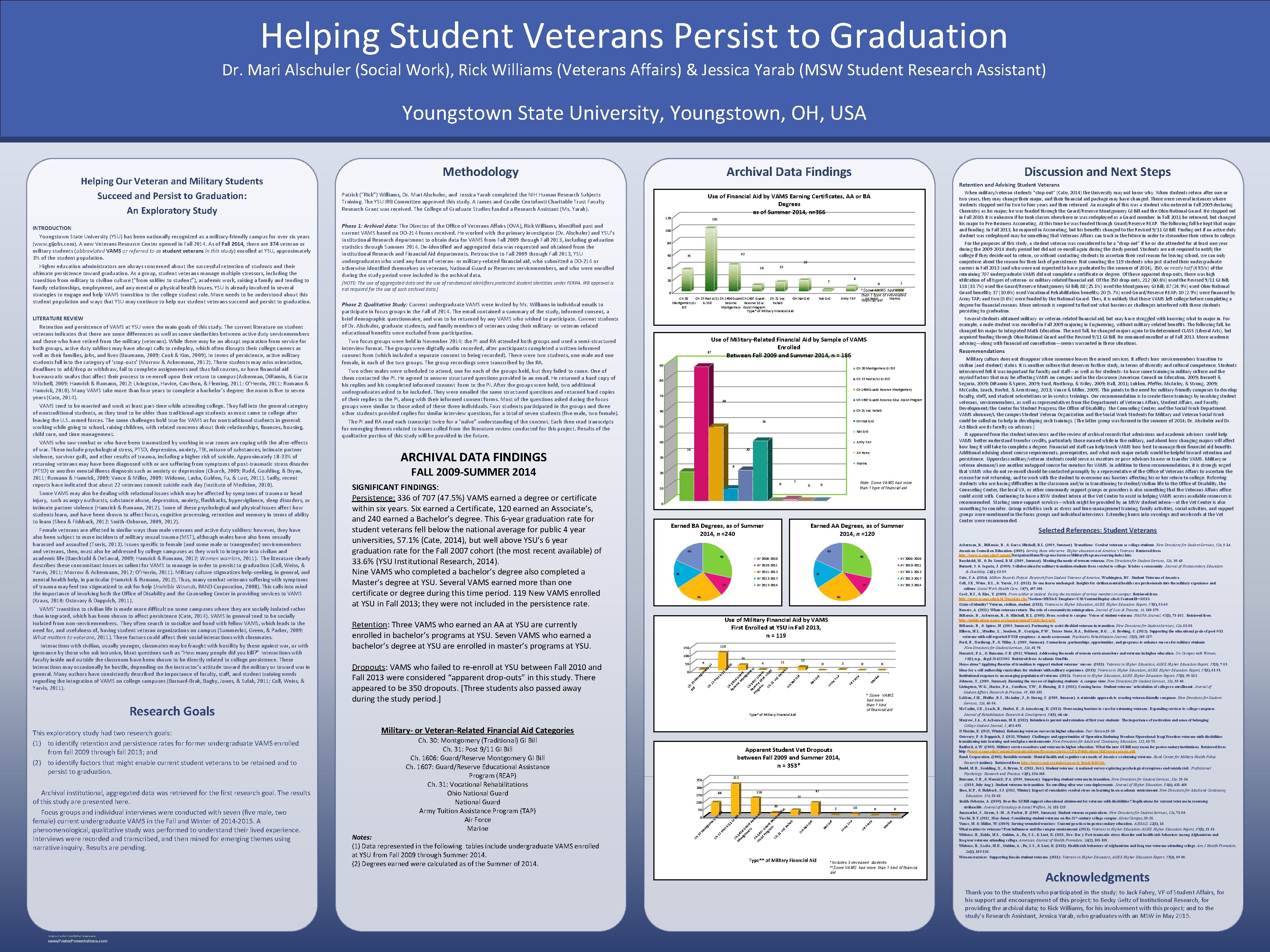

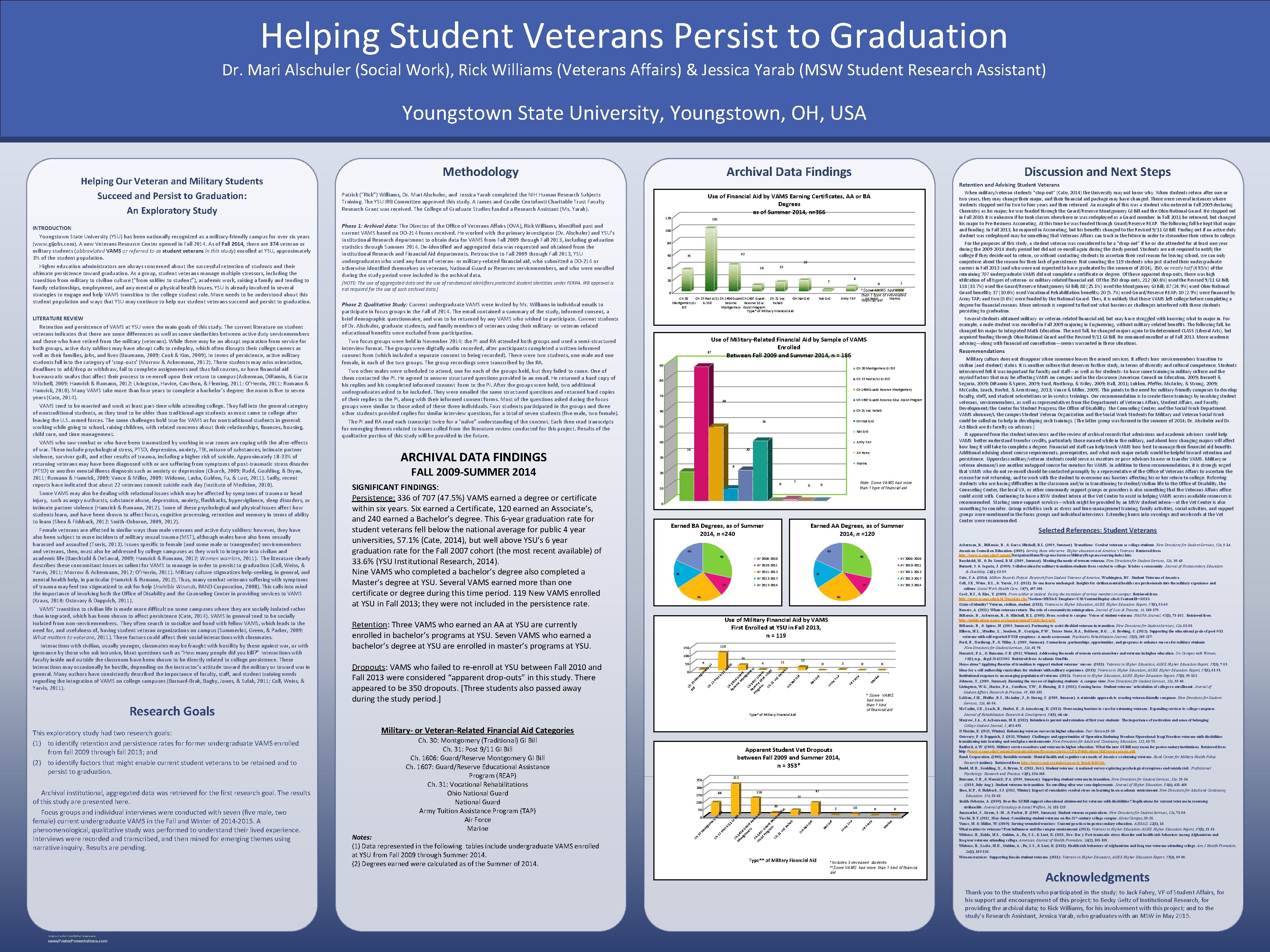

Helping Student Veterans Persist to Graduation Dr. Mari Alschuler (Social Work), Rick Williams (Veterans Affairs) & Jessica Yarab (MSW Student Research Assistant) Youngstown State University, Youngstown, OH, USA 100 80 60 43 35 18 40 15 10 20 8 3 Ch 30 Ch 33 Post 9/11 Ch 1606 Guard Ch 1607 Guard- Ch 31 Voc OH Nat Grd Montgomery GI GI Bill Reserve Educ Rehab Bill Montgomery Assist Program Type* of Military Financial Aid Nat Grd Use of Military-Related Financial Aid by Sample of VAMS Enrolled 87 Between Fall 2009 and Summer 2014, n = 186 90 Ch 33 Post 9/11 GI Bill 80 Ch 1606 Guard Reserve Montgomery 70 Ch 1607 Guard-Reserve Educ Assist Program 48 Ch 31 Voc Rehab 60 OH Nat Grd 39 50 Nat Grd Army TAP 30 Marine 8 20 0 10 1 Note: Some VAMS had more than 1 type of financial aid 0 0 0 Earned BA Degrees, as of Summer 2014, n =240 Earned AA Degrees, as of Summer 2014, n =120 44 44 68 68 AY 2009 -2010 AY 2010 -2011 AY 2011 -2012 38 AY 2012 -2013 26 AY 2013 -2014 64 Use of Military Financial Aid by VAMS First Enrolled at YSU in Fall 2013, n = 119 110 150 100 34 3 Bi ll Re 16 se 06 rv G e M uar on d tg om Ch er Re 16 y Pr se 07 og rve G ra E ua m du rd c. A ss Ch ist 31 Vo c. R eh ab OH Na t. G rd 0 0 0 Ai M r. F ar or in ce y. T AP m Ch Ar 1 /1 t 9 Po s 33 Ch e GI y. G tg om er 0 22 11 4 I 6 50 on Dropouts: VAMS who failed to re-enroll at YSU between Fall 2010 and Fall 2013 were considered “apparent drop-outs” in this study. There appeared to be 350 dropouts. [Three students also passed away during the study period. ] Air Force d Retention: Three VAMS who earned an AA at YSU are currently enrolled in bachelor’s programs at YSU. Seven VAMS who earned a bachelor’s degree at YSU are enrolled in master’s programs at YSU. 20 Gr SIGNIFICANT FINDINGS: Persistence: 336 of 707 (47. 5%) VAMS earned a degree or certificate within six years. Six earned a Certificate, 120 earned an Associate’s, and 240 earned a Bachelor’s degree. This 6 -year graduation rate for student veterans fell below the national average for public 4 year universities, 57. 1% (Cate, 2014), but well above YSU’s 6 year graduation rate for the Fall 2007 cohort (the most recent available) of 33. 6% (YSU Institutional Research, 2014). Nine VAMS who completed a bachelor’s degree also completed a Master’s degree at YSU. Several VAMS earned more than one certificate or degree during this time period. 119 New VAMS enrolled at YSU in Fall 2013; they were not included in the persistence rate. 19 * Some VAMS had more than 1 kind of financial aid Type* of Military Financial Aid Military- or Veteran-Related Financial Aid Categories 212 250 200 87 118 88 37 Type** of Military Financial Aid ar in e 0 M ce or y. T m Ar 0 r. F rd t. G Na OH 1 9/ 1 st Po 33 rd GI er 10 2 Na ill IB y. G 0 C Bi ll M h 16 on 0 tg 6 G om u er ard y Re se Ch rv As 16 e sis 07 t. P G ro ua gr rd am -R es er Ch ve 31 Ed Vo uc c. R eh ab 20 50 Ai 100 AP 150 Ch Notes: (1) Data represented in the following tables include undergraduate VAMS enrolled at YSU from Fall 2009 through Summer 2014. (2) Degrees earned were calculated as of the Summer of 2014. Apparent Student Vet Dropouts between Fall 2009 and Summer 2014, n = 353* om Ch. 30: Montgomery (Traditional) GI Bill Ch. 31: Post 9/11 GI Bill Ch. 1606: Guard/Reserve Montgomery GI Bill Ch. 1607: Guard/Reserve Educational Assistance Program (REAP) Ch. 31: Vocational Rehabilitations Ohio National Guard Army Tuition Assistance Program (TAP) Air Force Marine When military/veteran students “stop-out” (Cate, 2014) the University may not know why. When students return after one or two years, they may change their major, and their financial aid package may have changed. There were several instances where students stopped out for two to four years and then returned. An example of this was a student who entered in Fall 2009 declaring Chemistry as his major; he was funded through the Guard/Reserve Montgomery GI Bill and the Ohio National Guard. He stopped out in Fall 2010; it is unknown if he took classes elsewhere or was redeployed as a Guard member. In Fall 2011 he returned, but changed his major to Pre-Business Accounting. At this time he was funded through Guard/Reserve REAP. The following fall he kept that major and funding. In Fall 2013, he majored in Accounting, but his benefits changed to the Revised 9/11 GI Bill. Finding out if an active duty student was redeployed may be something that Veterans Affairs can track in the future in order to streamline their return to college. For the purposes of this study, a student veteran was considered to be a “drop-out” if he or she attended for at least one year during the 2009 -2014 study period but did not re-enroll again during the study period. Students are not required to notify the college if they decide not to return, so without contacting students to ascertain their real reason for leaving school, we can only conjecture about the reason for their lack of persistence. Not counting the 119 students who just started their undergraduate careers in Fall 2013 (and who were not expected to have graduated by the summer of 2014), 350, or nearly half (49. 5%) of the remaining 707 undergraduate VAMS did not complete a certificate or degree. Of these apparent drop-outs, there was high utilization of all types of veteran- or military-related financial aid. Of the 350 drop-outs, 212 (60. 6%) used the Revised 9/11 GI Bill; 118 (33. 7%) used the Guard/Reserve Montgomery GI Bill; 88 (25. 1%) used the Montgomery GI Bill; 87 (24. 9%) used Ohio National Guard benefits; 37 (10. 6%) used Vocational Rehabilitation benefits; 20 (5. 7%) used Guard/Reserve REAP; 10 (2. 9%) were financed by Army TAP; and two (0. 6%) were funded by the National Guard. Thus, it is unlikely that these VAMS left college before completing a degree for financial reasons. More outreach is required to find out what barriers or challenges interfered with these students persisting to graduation. Several students obtained military- or veteran-related financial aid, but may have struggled with knowing what to major in. For example, a male student was enrolled in Fall 2009 majoring in Engineering, without military-related benefits. The following fall, he changed his major to Integrated Math Education. The next fall, he changed majors again to Undetermined CLASS (Liberal Arts), but acquired funding through Ohio National Guard and the Revised 9/11 GI Bill. He remained enrolled as of Fall 2013. More academic advising—along with financial aid consultation—seems warranted in these situations. Recommendations Ch 30 Montgomery GI Bill Na t FALL 2009 -SUMMER 2014 *Some VAMS had more than 1 type of vet-related Air Forceaid Marine financial Army TAP 40 ARCHIVAL DATA FINDINGS 1 0 0 tg Archival institutional, aggregated data was retrieved for the first research goal. The results of this study are presented here. Focus groups and individual interviews were conducted with seven (five male, two female) current undergraduate VAMS in the Fall and Winter of 2014 -2015. A phenomenological, qualitative study was performed to understand their lived experience. Interviews were recorded and transcribed, and then mined for emerging themes using narrative inquiry. Results are pending. 101 on This exploratory study had two research goals: (1) to identify retention and persistence rates former undergraduate VAMS enrolled from fall 2009 through fall 2013; and (2) to identify factors that might enable current student veterans to be retained and to persist to graduation. 120 [NOTE: The use of aggregated data and the use of randomized identifiers protected student identities under FERPA. IRB approval is not required for the use of such archival data. ] Phase 2: Qualitative Study: Current undergraduate VAMS were invited by Mr. Williams in individual emails to participate in focus groups in the Fall of 2014. The email contained a summary of the study, informed consent, a brief demographic questionnaire, and was to be returned by any VAMS who wished to participate. Current students of Dr. Alschuler, graduate students, and family members of veterans using their military- or veteran-related educational benefits were excluded from participation. Two focus groups were held in November 2014; the PI and RA attended both groups and used a semi-structured interview format. The groups were digitally audio recorded, after participants completed a written informed consent form (which included a separate consent to being recorded). There were two students, one male and one female, in each of the two groups. The group recordings were transcribed by the RA. Two other males were scheduled to attend, one for each of the groups held, but they failed to come. One of them contacted the PI. He agreed to answer structured questions provided in an email. He returned a hard copy of his replies and his completed informed consent form to the PI. After the groups were held, two additional undergraduates asked to be included. They were emailed the same structured questions and returned hard copies of their replies to the PI, along with their informed consent forms. Most of the questions asked during the focus groups were similar to those asked of these three individuals. Four students participated in the groups and three other students provided replies for similar interview questions, for a total of seven students (five male, two female). The PI and RA read each transcript twice for a “naïve” understanding of the content. Each then read transcripts for emerging themes related to issues culled from the literature review conducted for this project. Results of the qualitative portion of this study will be provided in the future. Use of Financial Aid by VAMS Earning Certificates, AA or BA Degrees as of Summer 2014, n=366 M Research Goals Patrick (“Rick”) Williams, Dr. Mari Alschuler, and Jessica Yarab completed the NIH Human Research Subjects Training. The YSU IRB Committee approved this study. A James and Coralie Centofanti Charitable Trust Faculty Research Grant was received. The College of Graduate Studies funded a Research Assistant (Ms. Yarab). Phase 1: Archival data: The Director of the Office of Veterans Affairs (OVA), Rick Williams, identified past and current VAMS based on DD-214 forms received. He worked with the primary investigator (Dr. Alschuler) and YSU’s Institutional Research department to obtain data for VAMS from Fall 2009 through Fall 2013, including graduation statistics through Summer 2014. De-identified and aggregated data was requested and obtained from the Institutional Research and Financial Aid departments. Retroactive to Fall 2009 through Fall 2013, YSU undergraduates who used any form of veteran- or military-related financial aid, who submitted a DD-214 or otherwise identified themselves as veterans, National Guard or Reserves servicemembers, and who were enrolled during the study period were included in the archival data. 30 LITERATURE REVIEW Retention and persistence of VAMS at YSU were the main goals of this study. The current literature on student veterans indicates that there are some differences as well as some similarities between active duty servicemembers and those who have retired from the military (veterans). While there may be an abrupt separation from service for both groups, active duty soldiers may have abrupt calls to redeploy, which often disrupts their college careers as well as their families, jobs, and lives (Baumann, 2009; Cook & Kim, 2009). In terms of persistence, active military students fall into the category of ‘stop-outs’ (Morrow & Ackermann, 2012). These students may miss orientation, deadlines to add/drop or withdraw, fail to complete assignments and thus fail courses, or have financial aid bureaucratic snafus that affect their process to re-enroll upon their return to campus (Ackerman, Di. Ramio, & Garza Mitchell, 2009; Hamrick & Rumann, 2012; Livingston, Havice, Cawthon, & Fleming, 2011; O’Herrin, 2011; Rumann & Hamrick, 2010). Many VAMS take more than four years to complete a bachelor’s degree; the norm is five to seven years (Cate, 2014). VAMS tend to be married and work at least part-time while attending college. They fall into the general category of nontraditional students, as they tend to be older than traditional-age students as most came to college after leaving the U. S. armed forces. The same challenges hold true for VAMS as for nontraditional students in general: working while going to school, raising children, with related concerns about their relationships, finances, housing, child care, and time management. VAMS who saw combat or who have been traumatized by working in war zones are coping with the after-effects of war. These include psychological stress, PTSD, depression, anxiety, TBI, misuse of substances, intimate partner violence, survivor guilt, and other results of trauma, including a higher risk of suicide. Approximately 18 -33% of returning veterans may have been diagnosed with or are suffering from symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) or another mental illness diagnosis such as anxiety or depression (Church, 2009; Rudd, Goulding, & Bryan, 2011; Rumann & Hamrick, 2009; Vance & Miller, 2009; Widome, Laska, Gulden, Fu, & Lust, 2011). Sadly, recent reports have indicated that about 22 veterans commit suicide each day (Institute of Medicine, 2010). Some VAMS may also be dealing with relational issues which may be affected by symptoms of trauma or head injury, such as angry outbursts, substance abuse, depression, anxiety, flashbacks, hypervigilance, sleep disorders, or intimate partner violence (Hamrick & Rumann, 2012). Some of these psychological and physical issues affect how students learn, and have been shown to affect focus, cognitive processing, retention and memory in terms of ability to learn (Shea & Fishback, 2012; Smith-Osborne, 2009, 2012). Female veterans are affected in similar ways than male veterans and active duty soldiers; however, they have also been subject to more incidents of military sexual trauma (MST), although males have also been sexually harassed and assaulted (Tseris, 2013). Issues specific to female (and some male or transgender) servicemembers and veterans, then, must also be addressed by college campuses as they work to integrate into civilian and academic life (Baechtold & De. Sawal, 2009; Hamrick & Rumann, 2012; Women warriors, 2011). The literature clearly describes these concomitant issues as salient for VAMS to manage in order to persist to graduation (Coll, Weiss, & Yarvis, 2011; Morrow & Ackermann, 2012; O’Herrin, 2011). Military culture stigmatizes help-seeking, in general, and mental health help, in particular (Hamrick & Rumann, 2012). Thus, many combat veterans suffering with symptoms of trauma may feel too stigmatized to ask for help (Invisible Wounds, RAND Corporation, 2008). This calls into mind the importance of involving both the Office of Disability and the Counseling Center in providing services to VAMS (Kraus, 2010; Ostovary & Dapprich, 2011). VAMS’ transition to civilian life is made more difficult on some campuses where they are socially isolated rather than integrated, which has been shown to affect persistence (Cate, 2014). VAMS in general tend to be socially isolated from non-servicemembers. They often search to socialize and bond with fellow VAMS, which leads to the need for, and usefulness of, having student veteran organizations on campus (Summerlot, Green, & Parker, 2009; What matters to veterans, 2011). These factors could affect their social interactions with classmates. Interactions with civilian, usually younger, classmates may be fraught with hostility by those against war, or with ignorance by those who ask intrusive, blunt questions such as “How many people did you kill? ” Interactions with faculty inside and outside the classroom have been shown to be directly related to college persistence. These interactions may occasionally be hostile, depending on the instructor’s attitude toward the military or toward war in general. Many authors have consistently described the importance of faculty, staff, and student training needs regarding the integration of VAMS on college campuses (Barnard-Brak, Bagby, Jones, & Sulak, 2011; Coll, Weiss, & Yarvis, 2011). Discussion and Next Steps Retention and Advising Student Veterans Ch INTRODUCTION Youngstown State University (YSU) has been nationally recognized as a military-friendly campus for over six years (www. gijobs. com). A new Veterans Resource Center opened in Fall 2014. As of Fall 2014, there are 374 veteran or military students (abbreviated VAMS or referred to as student veterans in this study) enrolled at YSU, approximately 3% of the student population. Higher education administrators are always concerned about the successful retention of students and their ultimate persistence toward graduation. As a group, student veterans manage multiple stressors, including the transition from military to civilian culture (“from soldier to student”), academic work, raising a family and tending to family relationships, employment, and any mental or physical health issues. YSU is already involved in several strategies to engage and help VAMS transition to the college student role. More needs to be understood about this student population and ways that YSU may continue to help our student veterans succeed and persist to graduation. Archival Data Findings C Bi h 30 ll M Helping Our Veteran and Military Students Succeed and Persist to Graduation: An Exploratory Study Methodology *Includes 3 deceased students **Some VAMS had more than 1 kind of financial aid Military culture does not disappear when someone leaves the armed services. It affects how servicemembers transition to civilian (and student) status. It is another culture that deserves further study, in terms of diversity and cultural competence. Students interviewed felt it was important for faculty and staff—as well as for students--to have some training in military culture and the myriad factors that may be affecting VAMS on campus and in the classroom (American Council on Education, 2009; Burnett & Segoria, 2009; Di. Ramio & Spires, 2009; Ford, Northrup, & Wiley, 2009; Hall, 2011; Lokken, Pfeffer, Mc. Auley, & Strong, 2009; Mc. Caslin, Leach, Herbst, & Armstrong, 2013; Vance & Miller, 2009). This points to the need for military-friendly campuses to develop faculty, staff, and student orientations or in-service trainings. Our recommendation is to create these trainings by involving student veterans, servicemembers, as well as representatives from the Departments of Veterans Affairs, Student Affairs, and Faculty Development; the Center for Student Progress; the Office of Disability; the Counseling Center; and the Social Work Department. VAMS alumnae/i, the campus Student Veteran Organization and the Social Work Students for Military and Veteran Social Work could be called on to help in developing such trainings. [The latter group was formed in the summer of 2014; Dr. Alschuler and Dr. Azi Block are its faculty co-advisors. ] It appeared from the student interviews and the review of archival records that admissions and academic advisors could help VAMS better understand transfer credits, particularly those earned while in the military, and about how changing majors will affect how long it will take to complete a degree. Financial aid staff can help teach VAMS how best to manage their financial aid benefits. Additional advising about course requirements, prerequisites, and what each major entails would be helpful toward retention and persistence. Upperclass military/veteran students could serve as mentors or peer advisors to new or transfer VAMS. Military or veteran alumnae/i are another untapped source for mentors for VAMS. In addition to these recommendations, it is strongly urged that VAMS who do not re-enroll should be contacted promptly by a representative of the Office of Veterans Affairs to ascertain the reason for not returning, and to work with the student to overcome any barriers affecting his or her return to college. Referring students who are having difficulties in the classroom and/or in transitioning to student/civilian life to the Office of Disability, the Counseling Center, the local VA, or other community support groups or providers is also something that the Veterans Affairs office could assist with. Continuing to have a BSW student intern at the Vet Center to assist in helping VAMS access available resources is recommended. Starting some support services—which might be provided by an MSW student intern—at the Vet Center is also something to consider. Group activities such as stress and time management training, family activities, social activities, and support groups were mentioned in the focus groups and individual interviews. Extending hours into evenings and weekends at the Vet Center were recommended. Selected References: Student Veterans Ackerman, R. , Di. Ramio, D. , & Garza Mitchell, R. L. (2009, Summer). Transitions: Combat veterans as college students. New Directions for Student Services, 126, 5 -14. American Council on Education. (2009). Serving those who serve: Higher education and America’s Veterans. Retrieved from http: //www. acenet. edu/Content/Navigation. Menu/Programs. Services/Military. Programs/serving/index. htm Baechtold, M. , & De Sawal, D. M. (2009, Summer). Meeting the needs of women veterans. New Directions for Student Services, 126, 35 -43. Burnett, S. & Segoria, J. (2009). Collaboration for military transition students from combat to college: It takes a community. Journal of Postsecondary Education & Disability, 22(1), 53 -59. Cate, C. A. (2014). Million Records Project: Research from Student Veterans of America. Washington, DC: Student Veterans of America. Coll, J. E. , Weiss, E. L. , & Yarvis, J. S. (2011). No one leaves unchanged: Insights for civilian mental health care professionals into the military experience and culture. Social Work Health Care, 50(7), 487 -500. Cook, B. J. , & Kim, Y. (2009). From soldier to student: Easing the transition of service members on campus. Retrieved from http: //www. acenet. edu/AM/Template. cfm? Section=HENA&Template=/CM/Content. Display. cfm&Content. ID=33233. Crisis of identity? Veteran, civilian, student. (2011). Veterans in Higher Education, ASHE Higher Education Report, 37(3), 53 -65. Demers, A. (2011). When veterans return: The role of community in reintegration. Journal of Loss & Trauma, 160 -179. Di. Ramio, D. , Ackerman, R. , & Mitchell, R. L. (2008). From combat to campus: Voices of student-veterans. NASPA Journal, 45(1), 73 -102. Retrieved from http: //publications. naspa. org/naspajournal/Vol 45/Iss 1/art 5 Di. Ramio, D. , & Spires, M. (2009, Summer). Partnering to assist disabled veterans in transition. New Directions for Student Services, 126, 81 -88. Ellison, M. L. , Mueller, L. , Smelson, D. , Corrigan, P. W. , Torres Stone, R. A. , Bokhour, B. G…, & Drebing, C. (2012). Supporting the educational goals of post-9/11 veterans with self-reported PTSD symptoms: A needs assessment. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal, 35(3), 209 -217. Ford, D. , Northrup, P. , & Wiley, L. (2009, Summer). Connections, partnerships, opportunities, and programs to enhance success for military students. New Directions for Student Services, 126, 61 -70. Hamrick, F. A. , & Rumann, C. B. (2012, Winter). Addressing the needs of women servicemembers and veterans in higher education. On Campus with Women, 40(3), n. p. , dsgcl. 284222062. Retrieved from Academic One. File. Home alone? Applying theories of transition to support student veterans’ success. (2011). Veterans in Higher Education, ASHE Higher Education Report, 37(3), 7 -19. Ideas for a self-authorship curriculum for students with military experience. (2011). Veterans in Higher Education, ASHE Higher Education Report, 37(3), 81 -91. Institutional response to an emerging population of veterans. (2011). Veterans in Higher Education, ASHE Higher Education Report, 37(3), 95 -112. Johnson, T. , (2009, Summer). Ensuring the success of deploying students: A campus view. New Directions for Student Services, 126, 55 -60. Livingston, W. G. , Havice, P. A. , Cawthon, T. W. , & Fleming, D. S. (2011). Coming home: Student veterans’ articulation of college re-enrollment. Journal of Student Affairs Research & Practice, 48, 315 -331. Lokken, J. M. , Pfeffer, D. S. , Mc. Auley, J. , & Strong, C. (2009, Summer). A statewide approach to creating veteran-friendly campuses. New Directions for Student Services, 126, 45 -54. Mc. Caslin, S. E. , Leach, B. , Herbst, E. , & Armstrong, K. (2013). Overcoming barriers to care for returning veterans: Expanding services to college campuses. Journal of Rehabilitation Research & Development, 50(8), vii-xiv. Morrow, J. A. , & Ackermann, M. E. (2012). Intention to persist and retention of first year students: The importance of motivation and sense of belonging. College Student Journal, 3, 483 -491. O’Herrin, E. (2011, Winter). Enhancing veteran success in higher education. Peer Review, 15 -18. Ostovary, F. & Dapprich, J. (2011, Winter). Challenges and opportunities of Operation Enduring Freedom/Operational Iraqi Freedom veterans with disabilities transitioning into learning and workplace environments. New Directions for Adult and Continuing Education, 132, 63 -73. Radford, A. W. (2009). Military service members and veterans in higher education: What the new GI Bill may mean for postsecondary institutions. Retrieved from http: //www. acenet. edu/Content/Navigation. Menu/Programs. Servics/CPA/Publications/Mil. Service. errata. pdf Rand Corporation. (2008). Invisible wounds: Mental health and cognitive care needs of America’s returning veterans. Rand Center for Military Health Policy Research (online). Retrieved from http: //www. rand. org/pubs/research_briefs/RB 9336. Rudd, M. D. , Goulding, X. , & Bryan, X. (2011, Oct. ). Student veterans: A national survey exploring psychological symptoms and suicide risk. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 42(5), 354 -360. Rumann, C. B. , & Hamrick, F. A. (2009, Summer). Supporting student veterans in transition. New Directions for Student Services, 126, 25 -34. ---. (2010, July-Aug. ). Student veterans in transition: Re-enrolling after war zone deployments. Journal of Higher Education, 81(4), 431 -458. Shea, K. P. , & Fishback, S. J. (2012, Winter). Impact of cumulative combat stress on learning in an academic environment. New Directions for Adult and Continuing Education, 136, 53 -63. Smith-Osborne, A. (2009). Does the GI Bill support educational attainment for veterans with disabilities? Implications for current veterans in resuming civilian life. Journal of Sociology & Social Welfare, 36, 111 -125. Summerlot, J. , Green, S. -M. , & Parker, D. (2009, Summer). Student veteran organizations. New Directions for Student Services, 126, 71 -80. Vacchi, D. T. (2012, May-June). Considering student veterans on the 21 st century college campus. About Campus, 15 -21. Vance, M. & Miller, W. (2009). Serving wounded warriors: Current practices in postsecondary education. AHEAD, 22(1), 18. What matters to veterans? Peer influences and the campus environment. (2011). Veterans in Higher Education, ASHE Higher Education Report, 37(3), 21 -33. Widome, R. , Kehle, M. L. , Gulden, A. , Fu, S. S. , & Lust, K. (2011, Nov. -Dec. ). Post-traumatic stress disorder and health risk behaviors among Afghanistan and Iraq war veterans attending college. American Journal of Health Promotion, 26(2), 101 -108. Widome, R. , Laska, M. N. , Gulden, A. , Fu, S. S. , & Lust, K. (2011). Health risk behaviors of Afghanistan and Iraq war veterans attending college. Am J Health Promotion, 26(2), 109 -116. Women warriors: Supporting female student veterans. (2011). Veterans in Higher Education, ASHE Higher Education Report, 37(3), 69 -80. Acknowledgments Thank you to the students who participated in the study; to Jack Fahey, VP of Student Affairs, for his support and encouragement of this project; to Becky Geltz of Institutional Research, for providing the archival data; to Rick Williams, for his involvement with this project; and to the study’s Research Assistant, Jessica Yarab, who graduates with an MSW in May 2015. RESEARCH POSTER PRESENTATION DESIGN © 2012 www. Poster. Presentations. com