Hash Tables and Performance Analysis COMP 2521 18

Hash Tables and Performance Analysis COMP 2521 18 x 1

Hashing Key indexed arrays had perfect search performance O(1) • But required a dense range of index values. Otherwise memory is wasted Hashing allows us to approximate this performance while over coming the issues of Key Indexed arrays.

Hashing allows arbitrary types of keys Hashing maps keys into a compact range of index values • Items are stored in an array accessed by this index value Allows us to approach the ideal of title[hashfunction(“COMP 2521”)] = “Data Structures and Algorithms”;

Hashing A hash table implementation consists of two main parts: 1. A hash function to map each key to an index in the hash table (array of size N). • Key->[0. . N-1]

Hashing A hash table implementation consists of two main parts: 2. A collision resolution method so that • if hash table at the calculated index is already occupied with an item with a different key, an alternative slot can be found • Collisions are inevitable when dom(Key) > N

Hash Functions Requirements: • if the table has Table. Size entries, we need to hash keys to [0. . Table. Size-1] • the hash function should be cheap to compute • the hash function should ideally map the keys evenly to the index values - that is, every index should be generated with approximately the same probability o this is easy if the keys have a random distribution, but requires some thought otherwise

Hash functions Bad Hash Functions: First 3 digits of student id (yours are mainly 501518 as the id is based on enrolment year) Better Hash Functions: Last 3 digits of student id Simple method to hash keys: modular hash function • compute i%Table. Size • choose Table. Size to be prime

Hash functions Bad Hash Functions: First 3 digits of student id (yours are mainly 501518 as the id is based on enrolment year) Better Hash Functions: Last 3 digits of student id Even better: Use all digits in student id and a modular hash function

Hash functions Simple method to hash keys: modular hash function • compute i%Table. Size • choose Table. Size to be prime

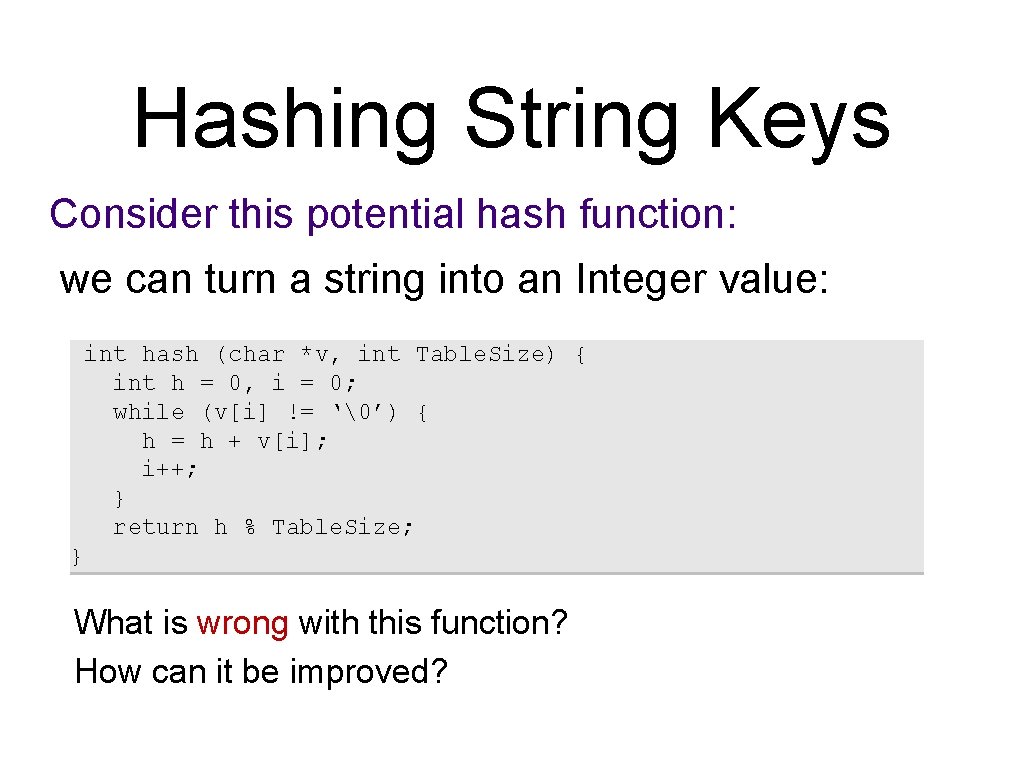

Hashing String Keys Consider this potential hash function: we can turn a string into an Integer value: int hash (char *v, int Table. Size) { int h = 0, i = 0; while (v[i] != ‘�’) { h = h + v[i]; i++; } return h % Table. Size; } What is wrong with this function? How can it be improved?

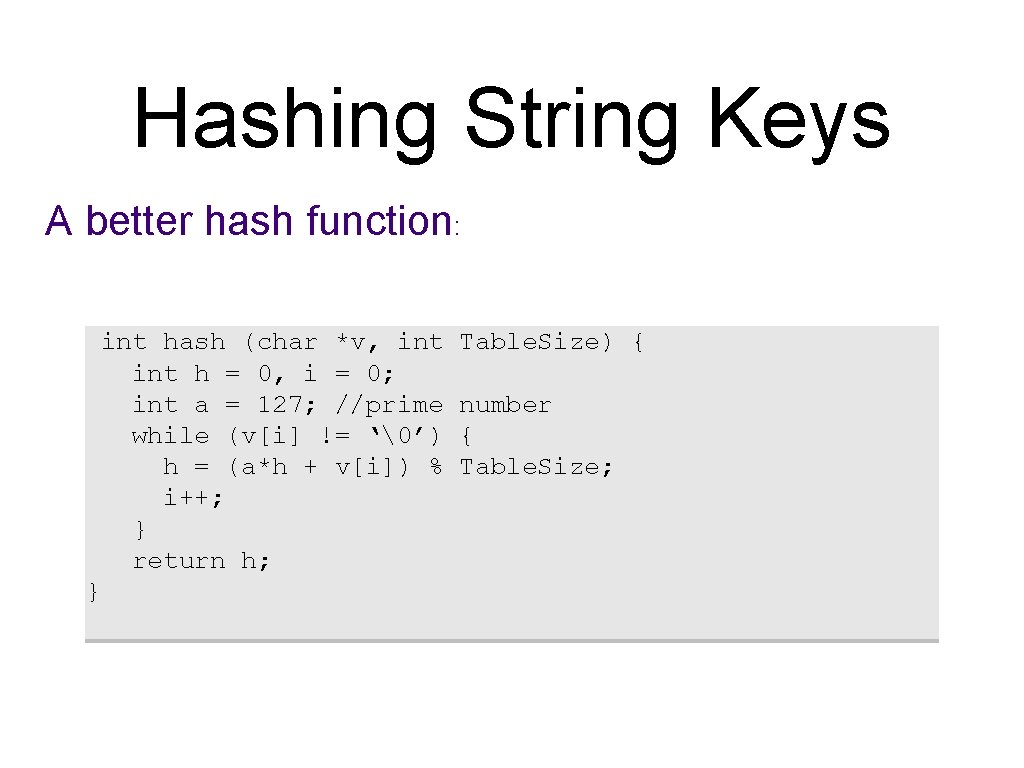

Hashing String Keys A better hash function: int hash (char *v, int h = 0, i = 0; int a = 127; //prime while (v[i] != ‘�’) h = (a*h + v[i]) % i++; } return h; } Table. Size) { number { Table. Size;

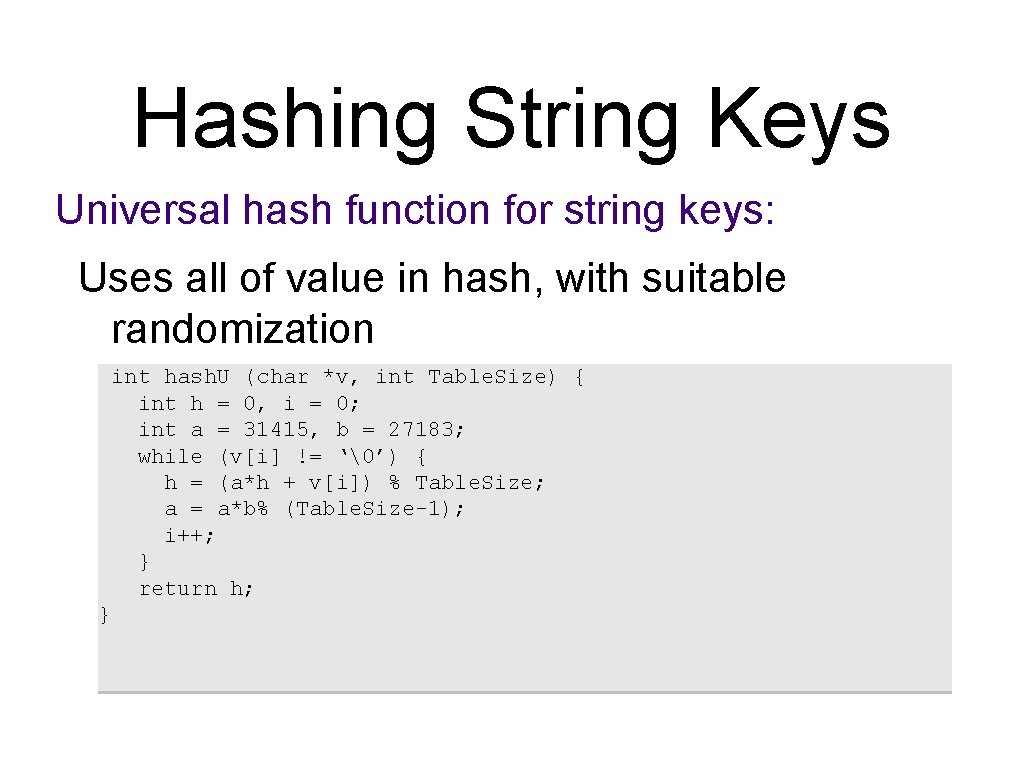

Hashing String Keys Universal hash function for string keys: Uses all of value in hash, with suitable randomization int hash. U (char *v, int Table. Size) { int h = 0, i = 0; int a = 31415, b = 27183; while (v[i] != ‘�’) { h = (a*h + v[i]) % Table. Size; a = a*b% (Table. Size-1); i++; } return h; }

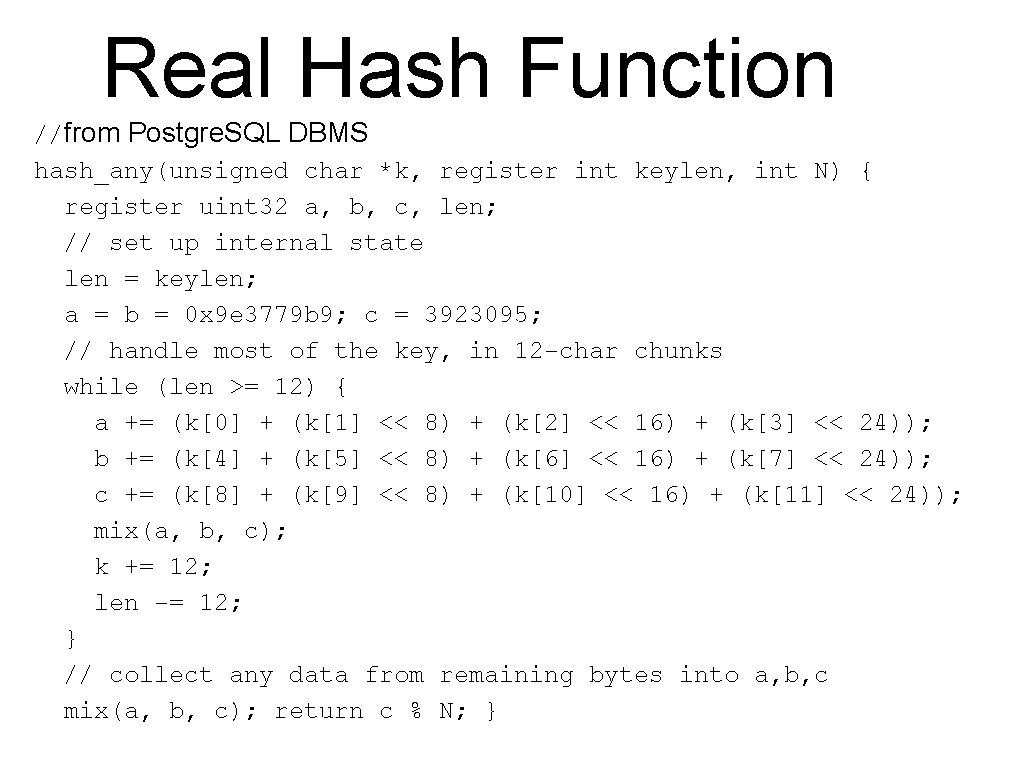

Real Hash Function //from Postgre. SQL DBMS hash_any(unsigned char *k, register int keylen, int N) { register uint 32 a, b, c, len; // set up internal state len = keylen; a = b = 0 x 9 e 3779 b 9; c = 3923095; // handle most of the key, in 12 -char chunks while (len >= 12) { a += (k[0] + (k[1] << 8) + (k[2] << 16) + (k[3] << 24)); b += (k[4] + (k[5] << 8) + (k[6] << 16) + (k[7] << 24)); c += (k[8] + (k[9] << 8) + (k[10] << 16) + (k[11] << 24)); mix(a, b, c); k += 12; len -= 12; } // collect any data from remaining bytes into a, b, c mix(a, b, c); return c % N; }

Collision Resolution: Separate Chaining What do we do if two entries have the same array index? • maintain a list of entries per array index (separate chaining) • use the next entry in the hash table (linear probing) • use a key dependent increment for probing (double hashing)

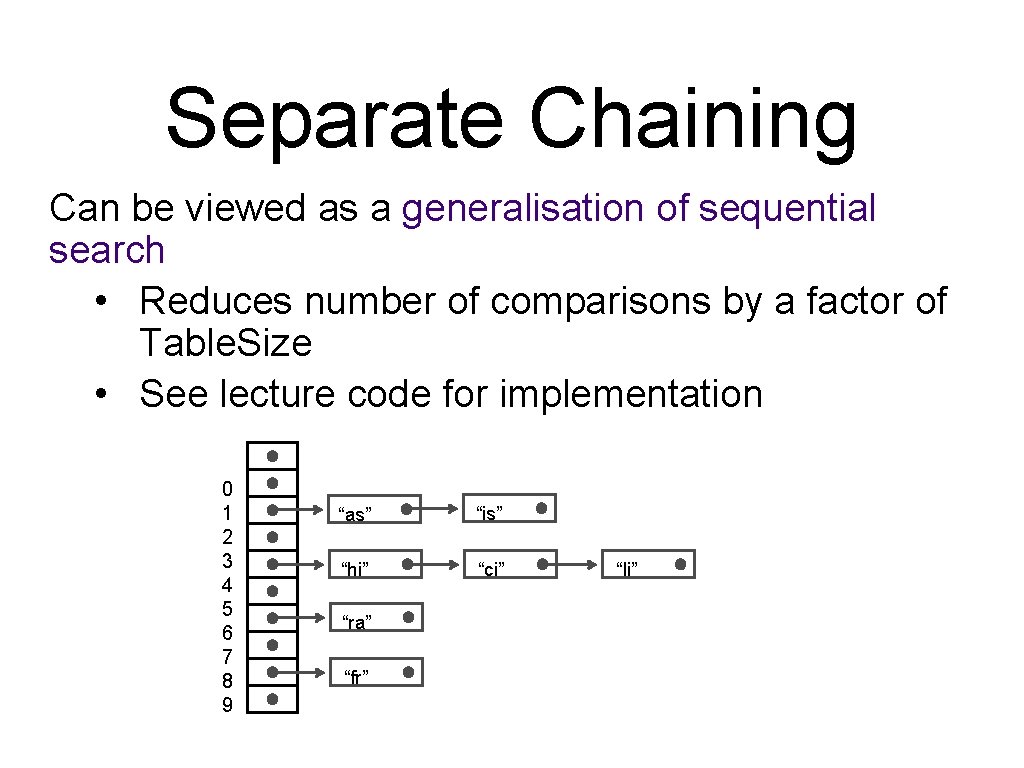

Separate Chaining Can be viewed as a generalisation of sequential search • Reduces number of comparisons by a factor of Table. Size • See lecture code for implementation 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 “as” “is” “hi” “ci” “ra” “fr” “li”

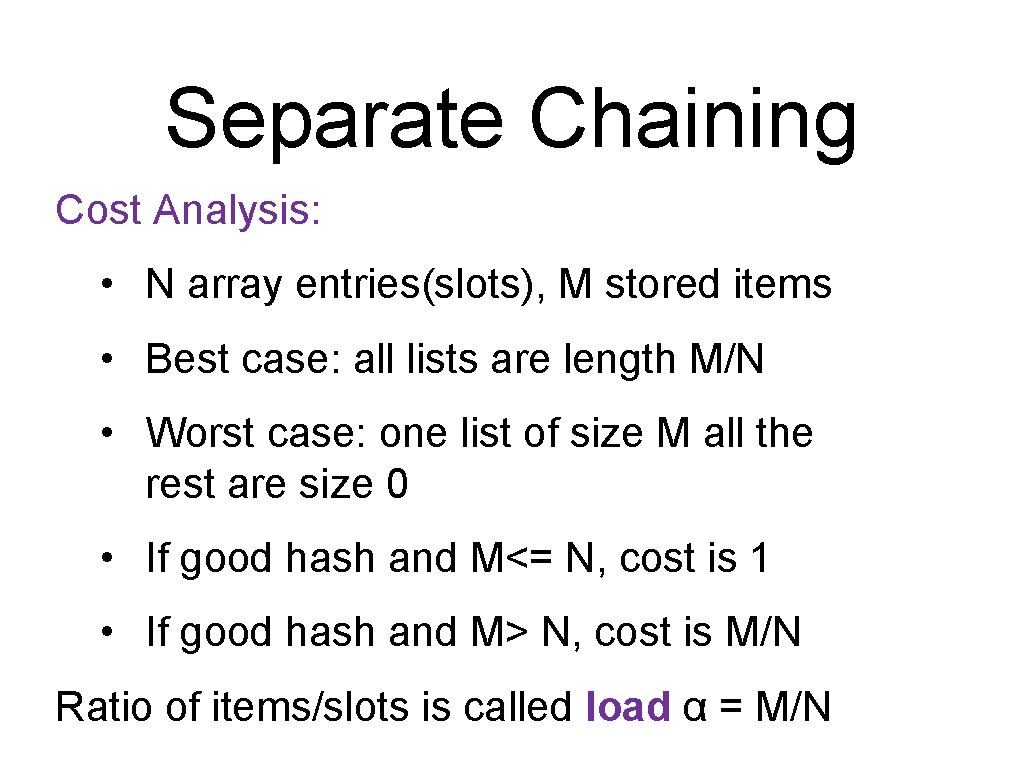

Separate Chaining Cost Analysis: • N array entries(slots), M stored items • Best case: all lists are length M/N • Worst case: one list of size M all the rest are size 0 • If good hash and M<= N, cost is 1 • If good hash and M> N, cost is M/N Ratio of items/slots is called load α = M/N

Linear Probing Resolve collision in the primary table: • if the table is not close to be full, there are many empty slots, even if we have a collision • in case of a collision, simply use the next available slot • this is an instance of open-addressing hashing

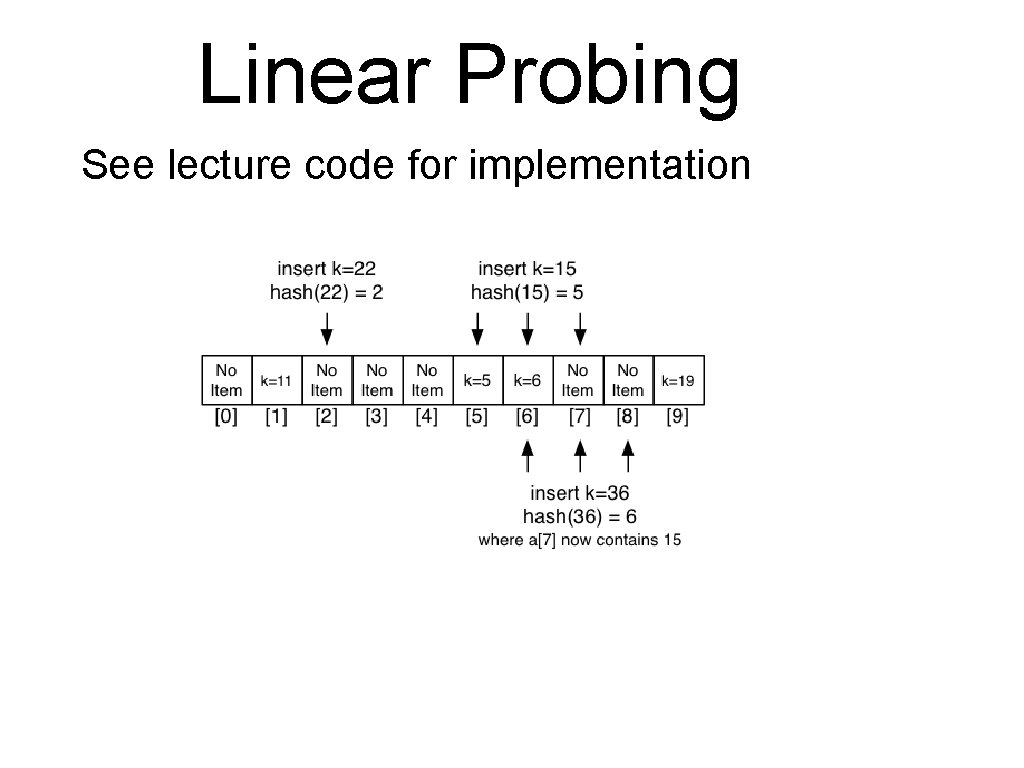

Linear Probing See lecture code for implementation

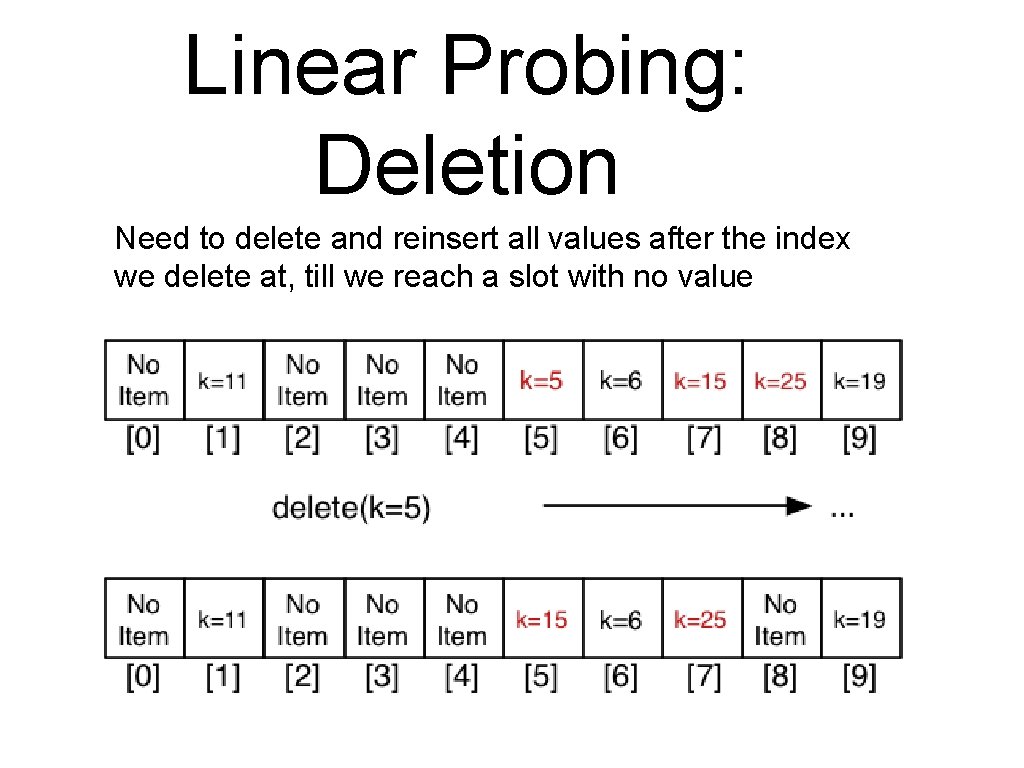

Linear Probing: Deletion Need to delete and reinsert all values after the index we delete at, till we reach a slot with no value

Linear Probing Cost Analysis: • Cost to reach location where item is mapped is O(1), but then we may have to scan along to find it or to find a place to insert it. • In the worst case this could be O(M) • affected by the load factor M/N

Linear Probing Problems: • When the table is starting to fill up, we can get clusters • Inserting an item with one hash value can increase access time for items with other hash values • Linear probing can become slow for near full hash tables

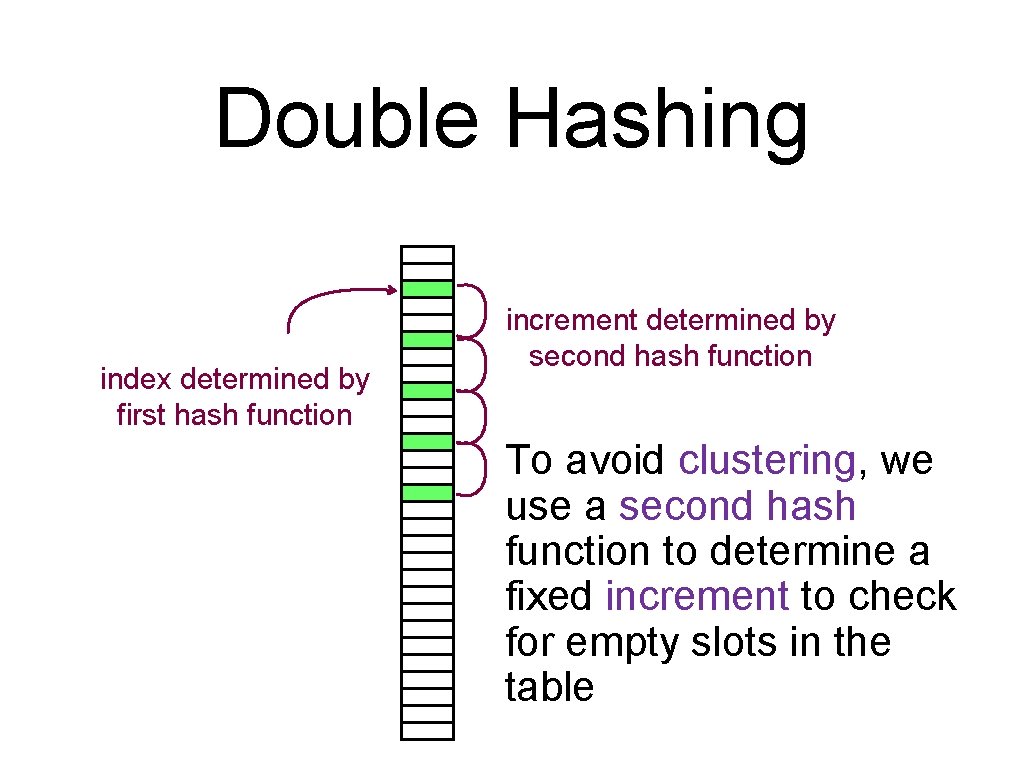

Double Hashing index determined by first hash function increment determined by second hash function To avoid clustering, we use a second hash function to determine a fixed increment to check for empty slots in the table

Double Hashing Requirements for second hashing function: • must never evaluate to zero • increment should be relatively prime to the hash table size. This ensures all elements are visited To generate relatively prime set table size to prime e. g. N=127. hash 2() in range [1. . N 1] where N 1 < 127 and prime Can be significantly faster than linear probing especially if the table is heavily loaded.

Double Hashing Deletion now becomes more difficult. • We can either rehash the whole table which is expensive. • Use lazy deletion ie. Mark elements as deleted rather than actually erasing them. • Deleted locations are treated as empty when inserting and occupied during a search.

Dynamic Hash Tables All the hash table methods we looked at so far have the same problem • once the hash table gets full, the search and insertion times increases due to collisions Solution: • grow table dynamically • this involves copying of table content, amortised over time by reduction of collisions

Evaluation Choice of the hash function can significantly effect the performance of the implementation, in particular when the hash table starts to fill up Choice of collision methods influences performance as well

Evaluation Collision method comparison: • linear probing: fastest, given table is sufficiently big • double hashing: makes most efficient use of memory, req. 2 nd hash function, fastest if table load is higher • separate chaining: table load can be more than 1 but performance degrades

Exercise Insert the following keys into a hashtable of size 11. 12, 11, 16, 10, 0, 21, 2 a) Use linear chaining b) Use linear probing c) Use double hashing with hashfunction 7 – k%7

Peformance Analysis Complexity/estimates give some idea of performance in advance. However in practice sometimes: • assumptions made in estimating performance are invalid • we overlook some frequent and/or expensive operation

Peformance Analysis Alternatively we can measure program execution: • coarse-grained. . . overview of performance characteristics. We have done this using the time command • fine-grained. . . detailed description of performance. We can do this using profiling.

Peformance Analysis Decades of empirical study of program execution have shown the 90/10 rule generally holds (or 80/20 rule or. . . ): • ``90% of the execution time is spent in 10% of the code'‘ Implications: • most of the code has little impact on overall performance • small regions of the code are bottlenecks (aka hot-spots) To significantly improve performance: make bottlenecks faster.

Execution Profiling Need a method for locating hot spots An execution profile for a program is • the total cost of performing each code block/function • for one execution of the program Cost may be measured via • a count of the number of times the block is executed • the total execution time spent within that block/function

Execution Profiling The gprof command displays execution profiles • . . . must compile program with the -pg flag • executing program creates an extra gmon. out file • gprof reads gmon. out and prints profile on stdout

gprof Example usage: gcc –pg –o xyz. c. /xyz < data > /dev/null gprof xyz | less For further usage see details: man gprof

gprof The gprof command works at the function level. It gives a table (flat profile) containing: • number of times each function was called • % of total execution time spent in the function • average execution time per call to that function • execution time for this function and its children

gprof Arranged in order from most expensive function down. It also gives a call graph, a list for each function: • which functions called this function • which functions were called by this function

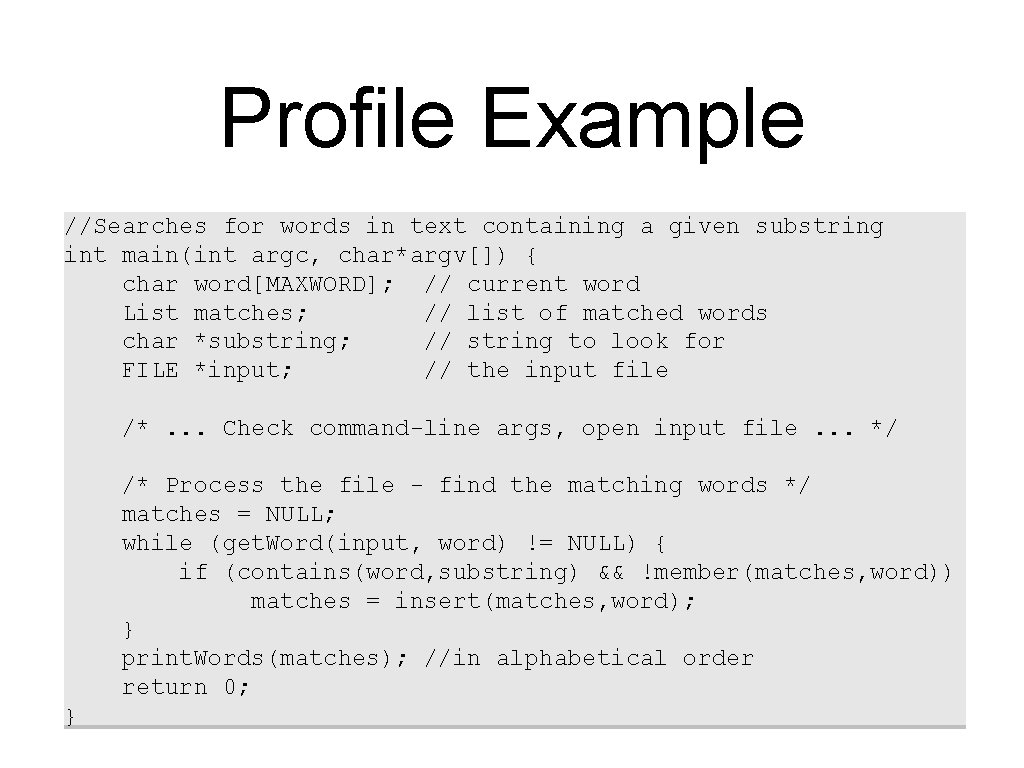

Profile Example //Searches for words in text containing a given substring int main(int argc, char*argv[]) { char word[MAXWORD]; // current word List matches; // list of matched words char *substring; // string to look for FILE *input; // the input file /*. . . Check command-line args, open input file. . . */ /* Process the file - find the matching words */ matches = NULL; while (get. Word(input, word) != NULL) { if (contains(word, substring) && !member(matches, word)) matches = insert(matches, word); } print. Words(matches); //in alphabetical order return 0; }

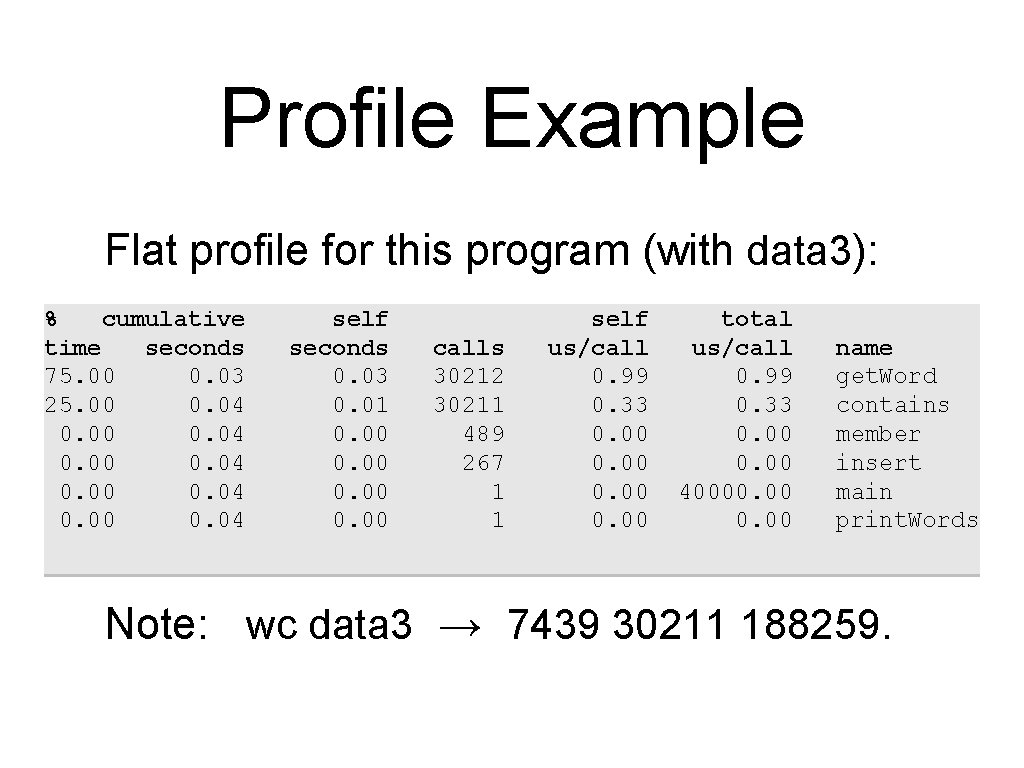

Profile Example Flat profile for this program (with data 3): % cumulative time seconds 75. 00 0. 03 25. 00 0. 04 0. 00 0. 04 self seconds 0. 03 0. 01 0. 00 calls 30212 30211 489 267 1 1 self us/call 0. 99 0. 33 0. 00 total us/call 0. 99 0. 33 0. 00 40000. 00 name get. Word contains member insert main print. Words Note: wc data 3 → 7439 30211 188259.

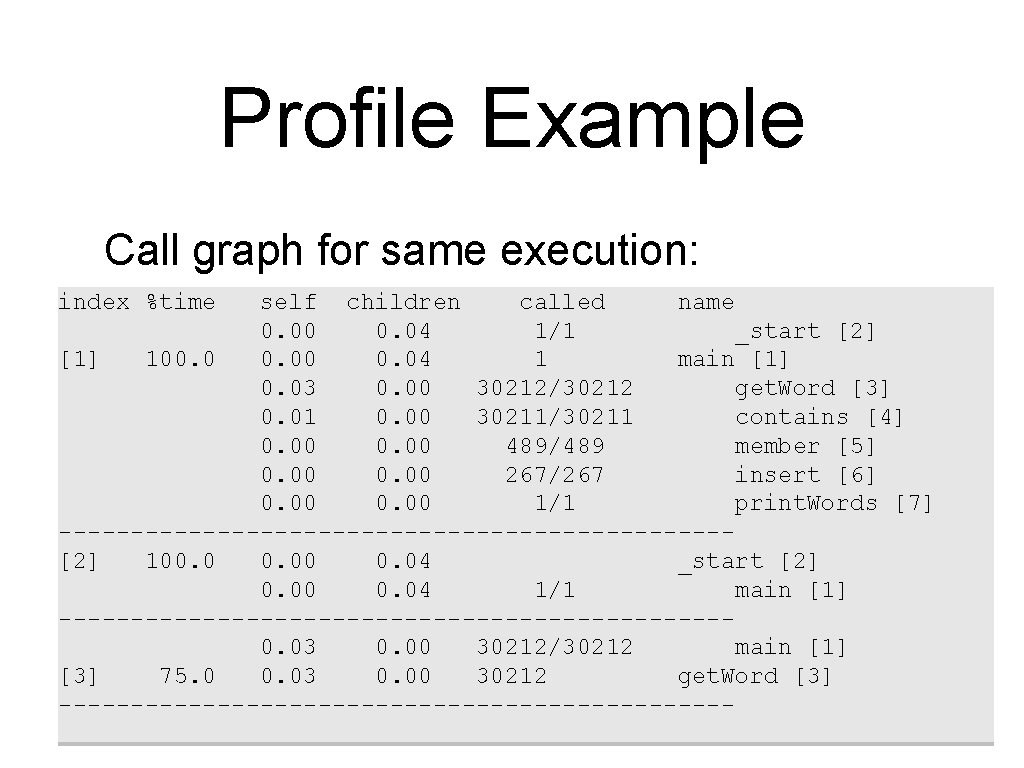

Profile Example Call graph for same execution: index %time self children called name 0. 00 0. 04 1/1 _start [2] [1] 100. 04 1 main [1] 0. 03 0. 00 30212/30212 get. Word [3] 0. 01 0. 00 30211/30211 contains [4] 0. 00 489/489 member [5] 0. 00 267/267 insert [6] 0. 00 1/1 print. Words [7] -----------------------[2] 100. 04 _start [2] 0. 00 0. 04 1/1 main [1] -----------------------0. 03 0. 00 30212/30212 main [1] [3] 75. 0 0. 03 0. 00 30212 get. Word [3] ------------------------

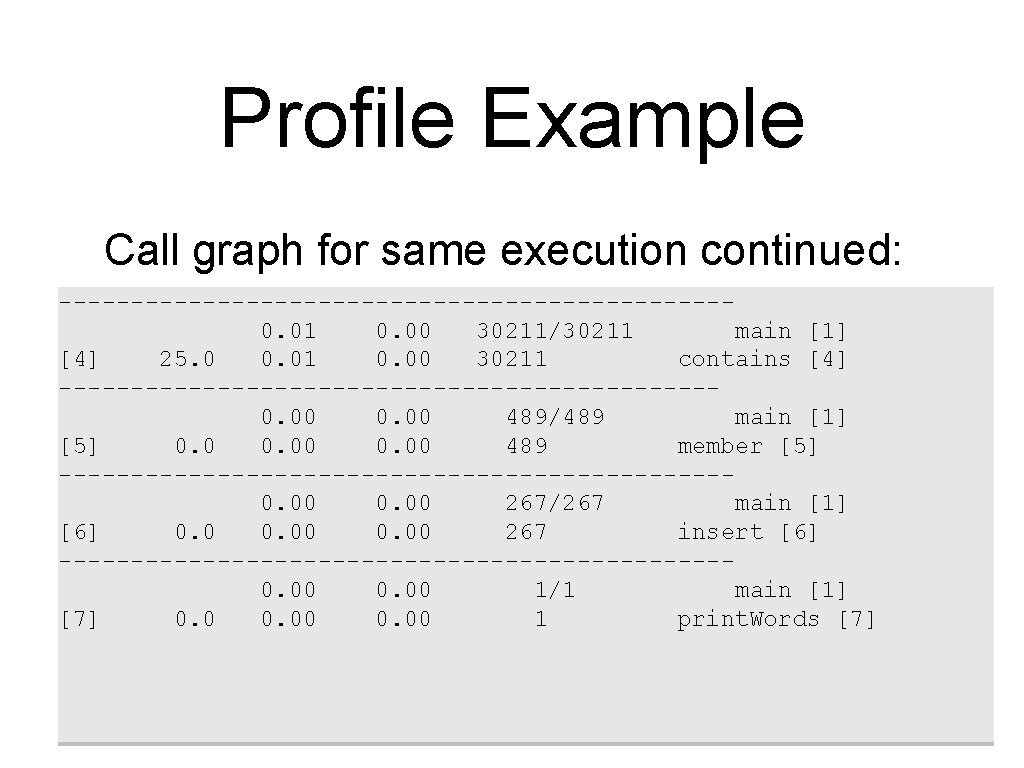

Profile Example Call graph for same execution continued: -----------------------0. 01 0. 00 30211/30211 main [1] [4] 25. 0 0. 01 0. 00 30211 contains [4] -----------------------0. 00 489/489 main [1] [5] 0. 00 489 member [5] -----------------------0. 00 267/267 main [1] [6] 0. 00 267 insert [6] -----------------------0. 00 1/1 main [1] [7] 0. 00 1 print. Words [7]

Conclusion Time and profile your code only when you are done Don’t optimize code unless you have to (you almost never will) Fixing your algorithm is almost always the solution Otherwise, running optimizing compiler is usually enough

- Slides: 41