GroupDelivered Video Modeling to Teach Pretend Play Skills

- Slides: 1

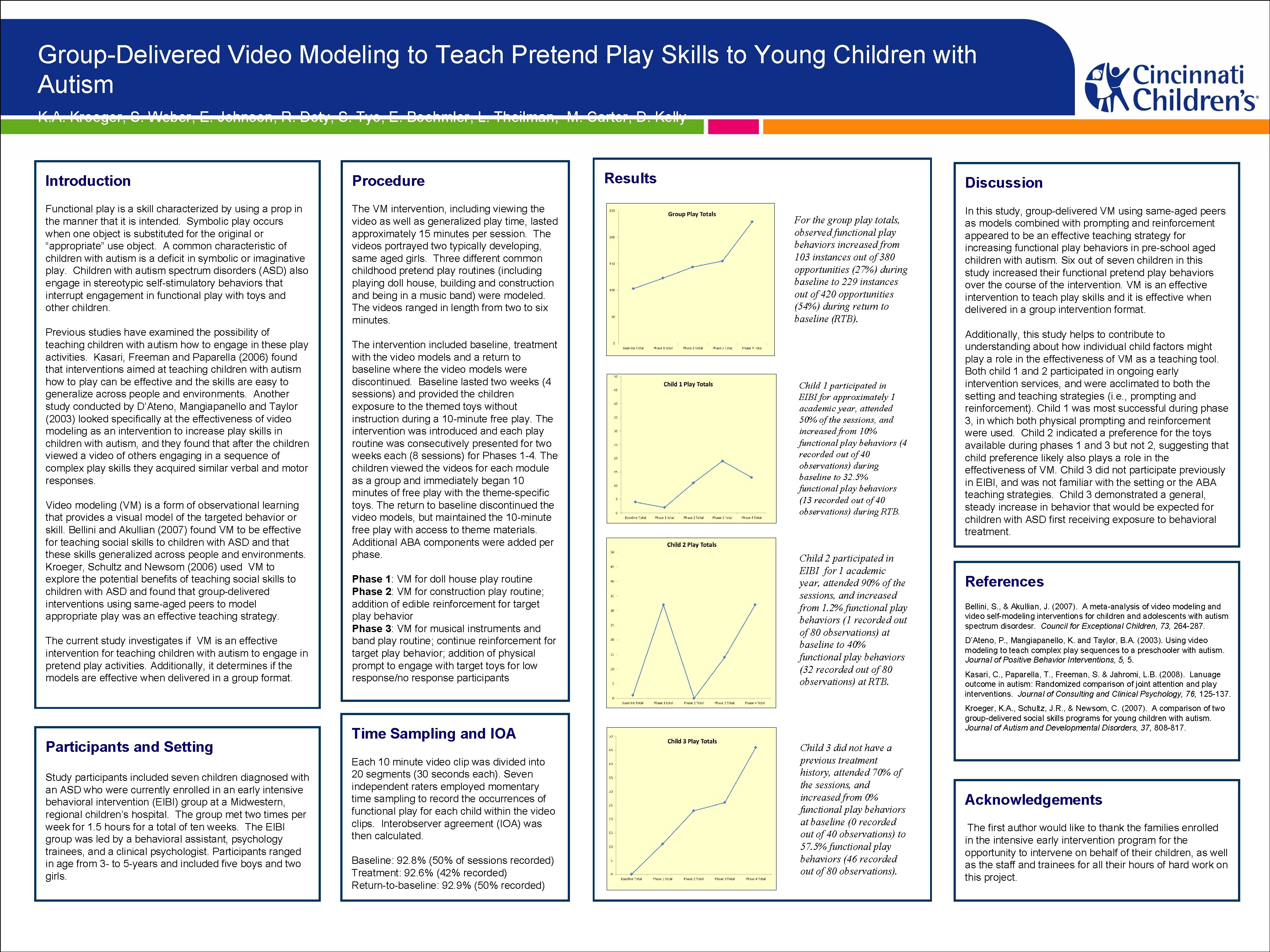

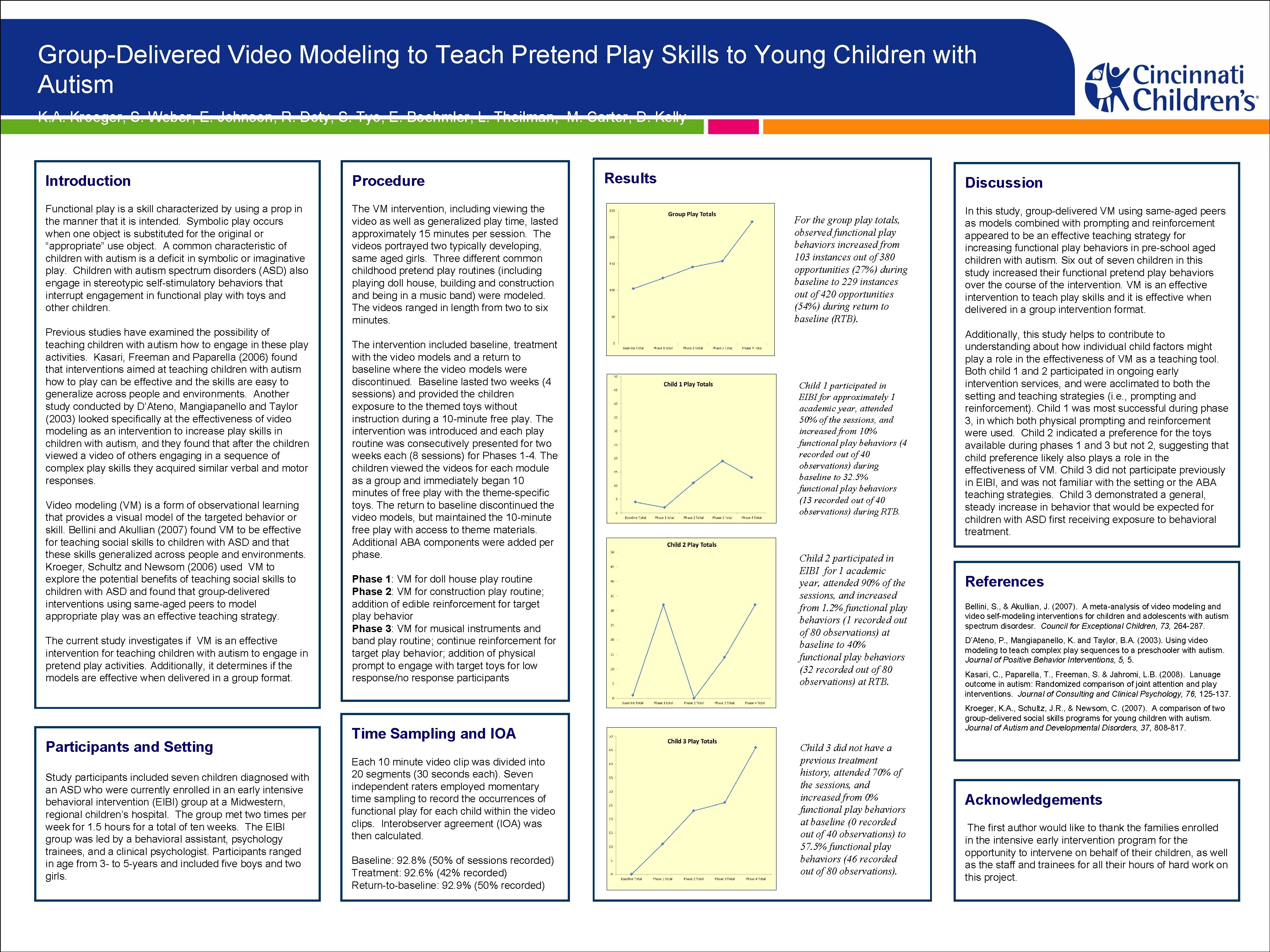

Group-Delivered Video Modeling to Teach Pretend Play Skills to Young Children with Autism K. A. Kroeger, S. Weber, E. Johnson, R. Doty, S. Tyo, E. Boehmler, L. Theilman, M. Carter, D. Kelly Introduction Procedure Functional play is a skill characterized by using a prop in the manner that it is intended. Symbolic play occurs when one object is substituted for the original or “appropriate” use object. A common characteristic of children with autism is a deficit in symbolic or imaginative play. Children with autism spectrum disorders (ASD) also engage in stereotypic self-stimulatory behaviors that interrupt engagement in functional play with toys and other children. The VM intervention, including viewing the video as well as generalized play time, lasted approximately 15 minutes per session. The videos portrayed two typically developing, same aged girls. Three different common childhood pretend play routines (including playing doll house, building and construction and being in a music band) were modeled. The videos ranged in length from two to six minutes. Previous studies have examined the possibility of teaching children with autism how to engage in these play activities. Kasari, Freeman and Paparella (2006) found that interventions aimed at teaching children with autism how to play can be effective and the skills are easy to generalize across people and environments. Another study conducted by D’Ateno, Mangiapanello and Taylor (2003) looked specifically at the effectiveness of video modeling as an intervention to increase play skills in children with autism, and they found that after the children viewed a video of others engaging in a sequence of complex play skills they acquired similar verbal and motor responses. Video modeling (VM) is a form of observational learning that provides a visual model of the targeted behavior or skill. Bellini and Akullian (2007) found VM to be effective for teaching social skills to children with ASD and that these skills generalized across people and environments. Kroeger, Schultz and Newsom (2006) used VM to explore the potential benefits of teaching social skills to children with ASD and found that group-delivered interventions using same-aged peers to model appropriate play was an effective teaching strategy. The current study investigates if VM is an effective intervention for teaching children with autism to engage in pretend play activities. Additionally, it determines if the models are effective when delivered in a group format. Participants and Setting Study participants included seven children diagnosed with an ASD who were currently enrolled in an early intensive behavioral intervention (EIBI) group at a Midwestern, regional children’s hospital. The group met two times per week for 1. 5 hours for a total of ten weeks. The EIBI group was led by a behavioral assistant, psychology trainees, and a clinical psychologist. Participants ranged in age from 3 - to 5 -years and included five boys and two girls. The intervention included baseline, treatment with the video models and a return to baseline where the video models were discontinued. Baseline lasted two weeks (4 sessions) and provided the children exposure to themed toys without instruction during a 10 -minute free play. The intervention was introduced and each play routine was consecutively presented for two weeks each (8 sessions) for Phases 1 -4. The children viewed the videos for each module as a group and immediately began 10 minutes of free play with theme-specific toys. The return to baseline discontinued the video models, but maintained the 10 -minute free play with access to theme materials. Additional ABA components were added per phase. Phase 1: VM for doll house play routine Phase 2: VM for construction play routine; addition of edible reinforcement for target play behavior Phase 3: VM for musical instruments and band play routine; continue reinforcement for target play behavior; addition of physical prompt to engage with target toys for low response/no response participants Results Discussion For the group play totals, observed functional play behaviors increased from 103 instances out of 380 opportunities (27%) during baseline to 229 instances out of 420 opportunities (54%) during return to baseline (RTB). Child 1 participated in EIBI for approximately 1 academic year, attended 50% of the sessions, and increased from 10% functional play behaviors (4 recorded out of 40 observations) during baseline to 32. 5% functional play behaviors (13 recorded out of 40 observations) during RTB. Child 2 participated in EIBI for 1 academic year, attended 90% of the sessions, and increased from 1. 2% functional play behaviors (1 recorded out of 80 observations) at baseline to 40% functional play behaviors (32 recorded out of 80 observations) at RTB. Baseline: 92. 8% (50% of sessions recorded) Treatment: 92. 6% (42% recorded) Return-to-baseline: 92. 9% (50% recorded) Additionally, this study helps to contribute to understanding about how individual child factors might play a role in the effectiveness of VM as a teaching tool. Both child 1 and 2 participated in ongoing early intervention services, and were acclimated to both the setting and teaching strategies (i. e. , prompting and reinforcement). Child 1 was most successful during phase 3, in which both physical prompting and reinforcement were used. Child 2 indicated a preference for the toys available during phases 1 and 3 but not 2, suggesting that child preference likely also plays a role in the effectiveness of VM. Child 3 did not participate previously in EIBI, and was not familiar with the setting or the ABA teaching strategies. Child 3 demonstrated a general, steady increase in behavior that would be expected for children with ASD first receiving exposure to behavioral treatment. References Bellini, S. , & Akullian, J. (2007). A meta-analysis of video modeling and video self-modeling interventions for children and adolescents with autism spectrum disordesr. Council for Exceptional Children, 73, 264 -287. D’Ateno, P. , Mangiapanello, K. and Taylor, B. A. (2003). Using video modeling to teach complex play sequences to a preschooler with autism. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions, 5, 5. Kasari, C. , Paparella, T. , Freeman, S. & Jahromi, L. B. (2008). Lanuage outcome in autism: Randomized comparison of joint attention and play interventions. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 76, 125 -137. Kroeger, K. A. , Schultz, J. R. , & Newsom, C. (2007). A comparison of two group-delivered social skills programs for young children with autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 37, 808 -817. Time Sampling and IOA Each 10 minute video clip was divided into 20 segments (30 seconds each). Seven independent raters employed momentary time sampling to record the occurrences of functional play for each child within the video clips. Interobserver agreement (IOA) was then calculated. In this study, group-delivered VM using same-aged peers as models combined with prompting and reinforcement appeared to be an effective teaching strategy for increasing functional play behaviors in pre-school aged children with autism. Six out of seven children in this study increased their functional pretend play behaviors over the course of the intervention. VM is an effective intervention to teach play skills and it is effective when delivered in a group intervention format. Child 3 did not have a previous treatment history, attended 70% of the sessions, and increased from 0% functional play behaviors at baseline (0 recorded out of 40 observations) to 57. 5% functional play behaviors (46 recorded out of 80 observations). Acknowledgements The first author would like to thank the families enrolled in the intensive early intervention program for the opportunity to intervene on behalf of their children, as well as the staff and trainees for all their hours of hard work on this project.