Gregor Mendel And The Genetic Revolution Timothy G

- Slides: 20

Gregor Mendel And The Genetic Revolution Timothy G. Standish, Ph. D. © 1999 Timothy G. Standish

Introduction- Gregor Mendel � Father of classical genetics. � Born Johan Mendel in 1822 to peasant family in the Czech village of Heinzendorf part of the Austro-Hungarian empire at the time. � Austrian Augustinian monk (Actually from Brunn which is now in the Czech Republic). © 1999 Timothy G. Standish

Gregor Mendel - Work � Starting in 1856 Mendel studied peas which he grew in a garden outside the Abbey where he lived. � Showed that the traits he studied behaved in a precise mathematical way and disproved theory of "blended inheritance. ” � Mendel’s work was rediscovered in 1900 by three botanists: – Carl Correns (Germany) – Erich von Tschermak (Austria) © 1999 Timothy G. Standish

Chromosomes: The Physical Basis of Inheritance � 1866 Mendel published his work � 1875 Mitosis was first described � 1890 s Meiosis was described � 1900 Mendel's work was rediscovered � 1902 Walter Sutton, Theodore Boveri and others noted parallels between behavior of chromosomes and alleles. © 1999 Timothy G. Standish

Why Peas? � Mendel used peas to study inheritance because: � True breeding commercial strains were available � Peas are easy to grow � Peas have many easy to observe traits including: – Seed color - Green or yellow – Seed shape - Round or wrinkled – Pod color - Green or yellow – Pod shape - Smooth or constricted – Flower color - White or purple – Flower position - Axial or terminal – Plant size - Tall or dwarf © 1999 Timothy G. Standish

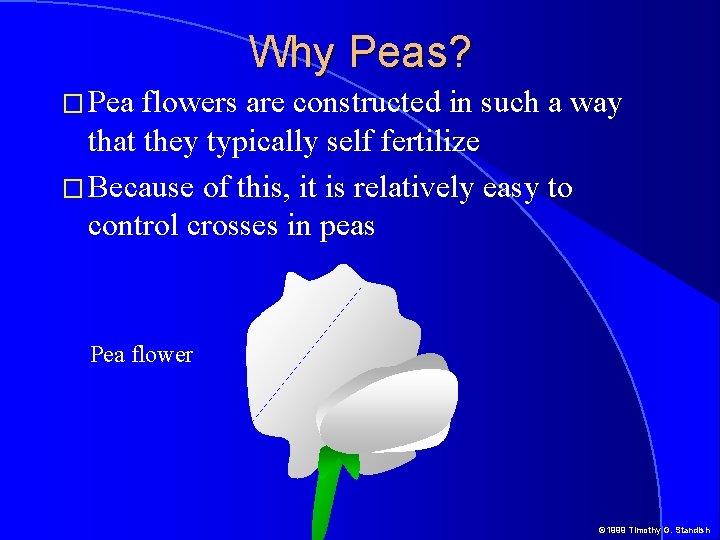

Why Peas? � Pea flowers are constructed in such a way that they typically self fertilize � Because of this, it is relatively easy to control crosses in peas Pea flower © 1999 Timothy G. Standish

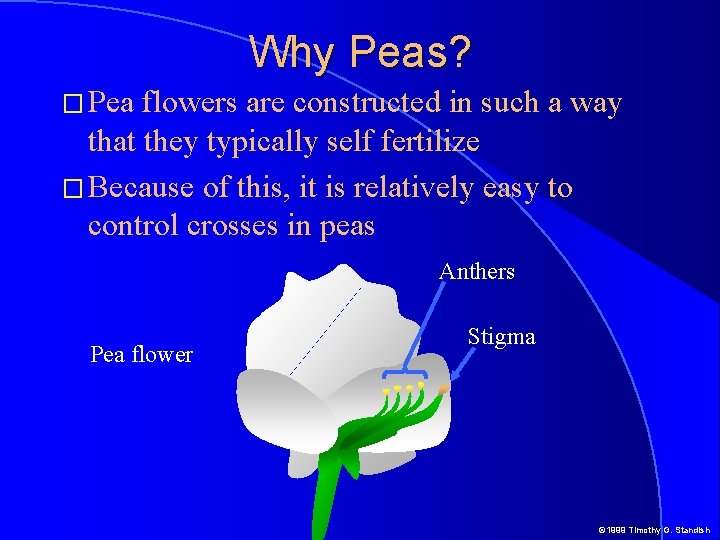

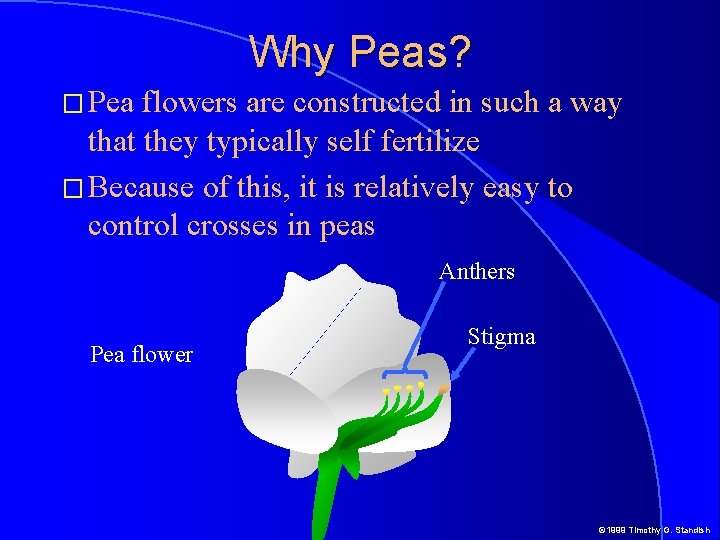

Why Peas? � Pea flowers are constructed in such a way that they typically self fertilize � Because of this, it is relatively easy to control crosses in peas Anthers Pea flower Stigma © 1999 Timothy G. Standish

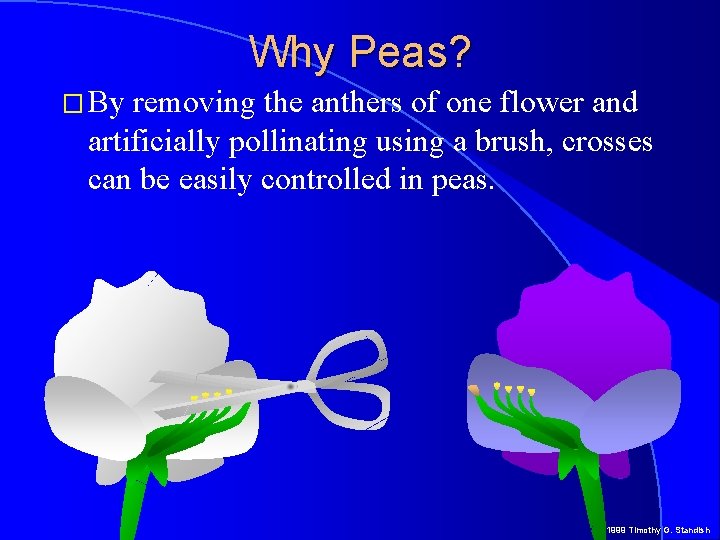

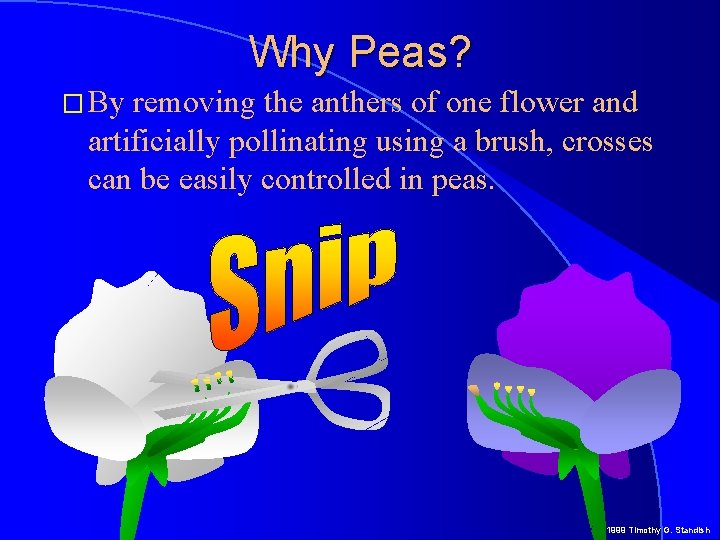

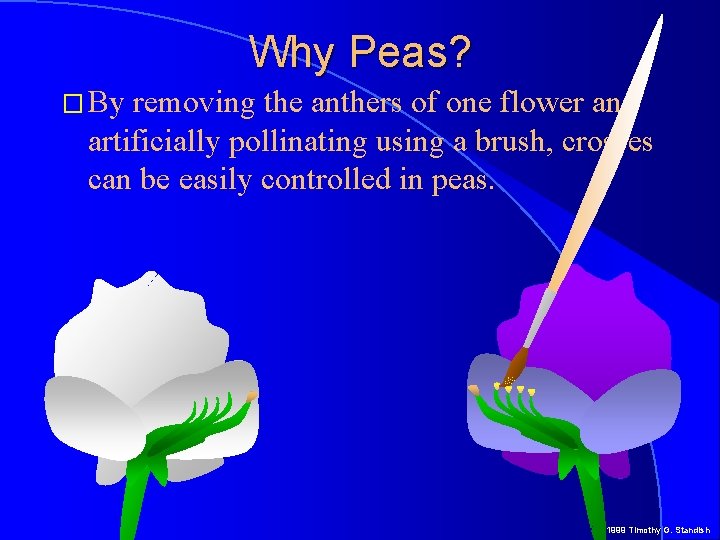

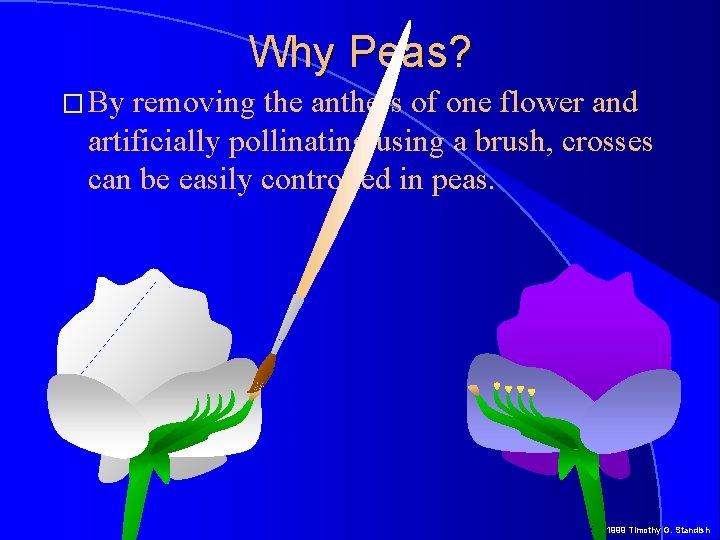

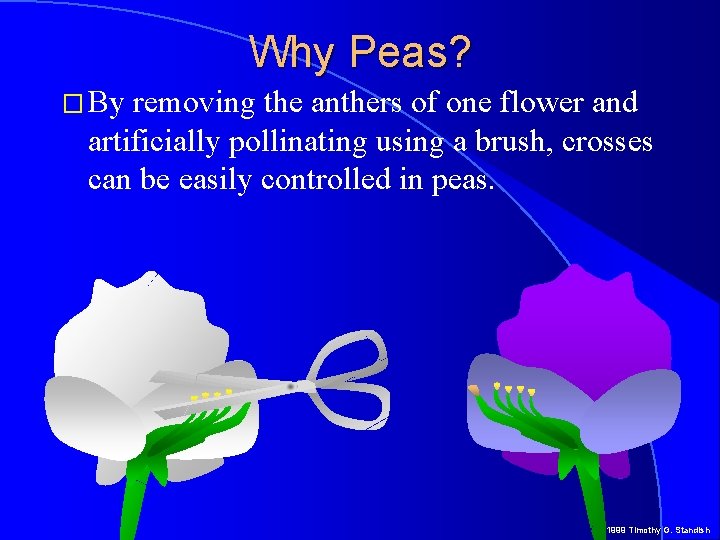

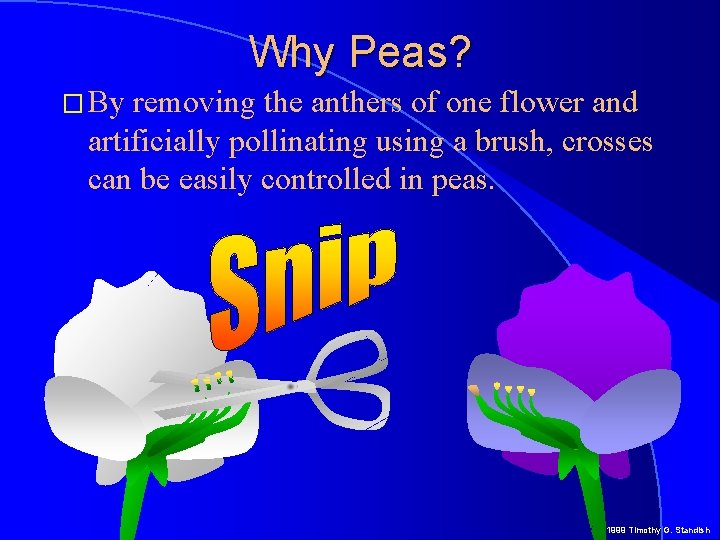

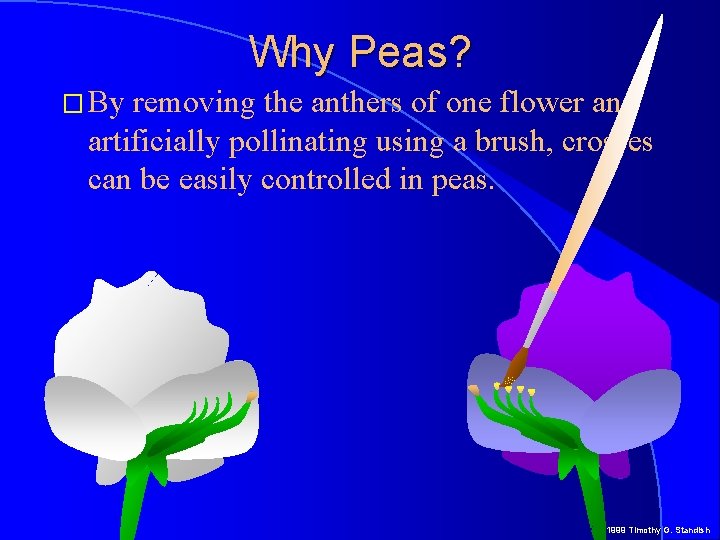

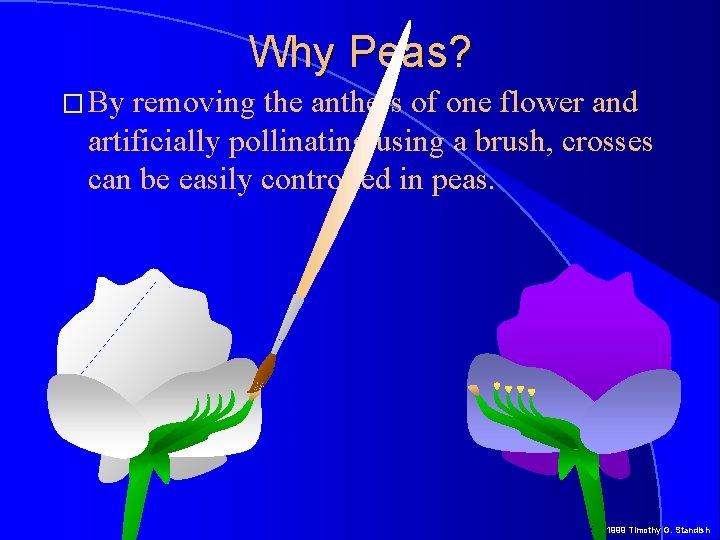

Why Peas? � By removing the anthers of one flower and artificially pollinating using a brush, crosses can be easily controlled in peas. © 1999 Timothy G. Standish

Why Peas? � By removing the anthers of one flower and artificially pollinating using a brush, crosses can be easily controlled in peas. © 1999 Timothy G. Standish

Why Peas? � By removing the anthers of one flower and artificially pollinating using a brush, crosses can be easily controlled in peas. . . © 1999 Timothy G. Standish

Why Peas? � By removing the anthers of one flower and artificially pollinating using a brush, crosses can be easily controlled in peas. . . © 1999 Timothy G. Standish

Why Peas? � By removing the anthers of one flower and artificially pollinating using a brush, crosses can be easily controlled in peas. . © 1999 Timothy G. Standish

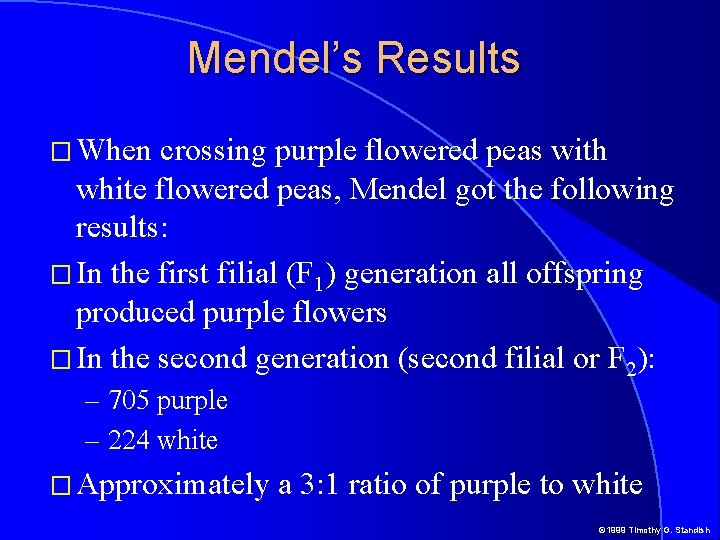

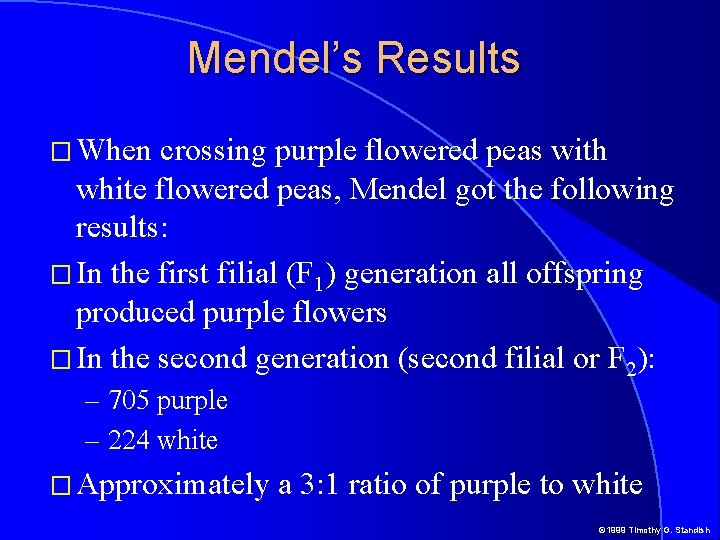

Mendel’s Results � When crossing purple flowered peas with white flowered peas, Mendel got the following results: � In the first filial (F 1) generation all offspring produced purple flowers � In the second generation (second filial or F 2): – 705 purple – 224 white � Approximately a 3: 1 ratio of purple to white © 1999 Timothy G. Standish

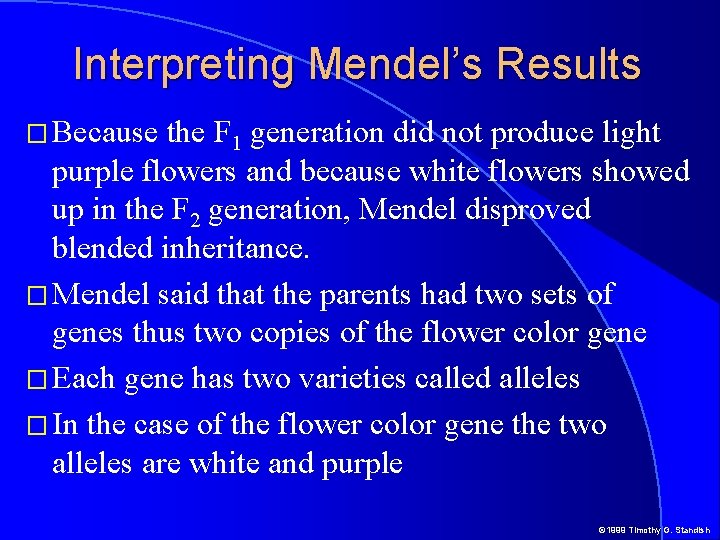

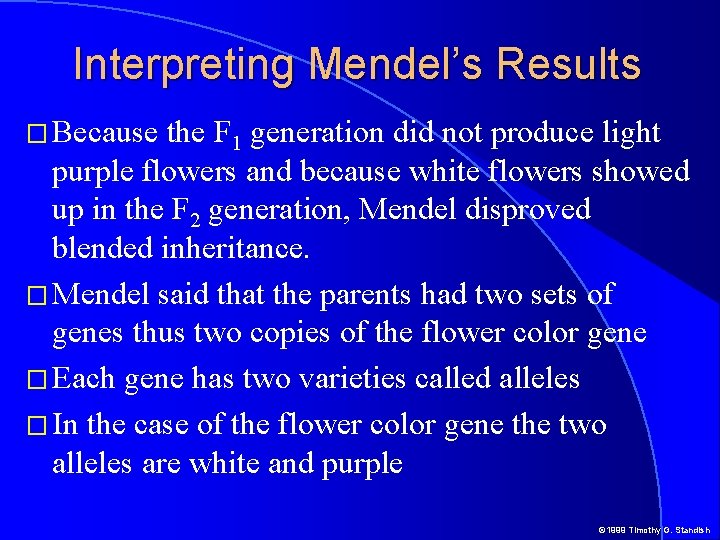

Interpreting Mendel’s Results � Because the F 1 generation did not produce light purple flowers and because white flowers showed up in the F 2 generation, Mendel disproved blended inheritance. � Mendel said that the parents had two sets of genes thus two copies of the flower color gene � Each gene has two varieties called alleles � In the case of the flower color gene the two alleles are white and purple © 1999 Timothy G. Standish

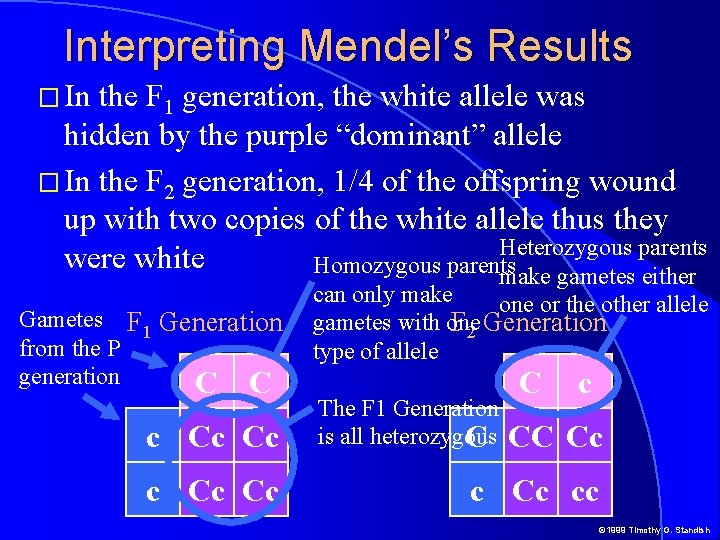

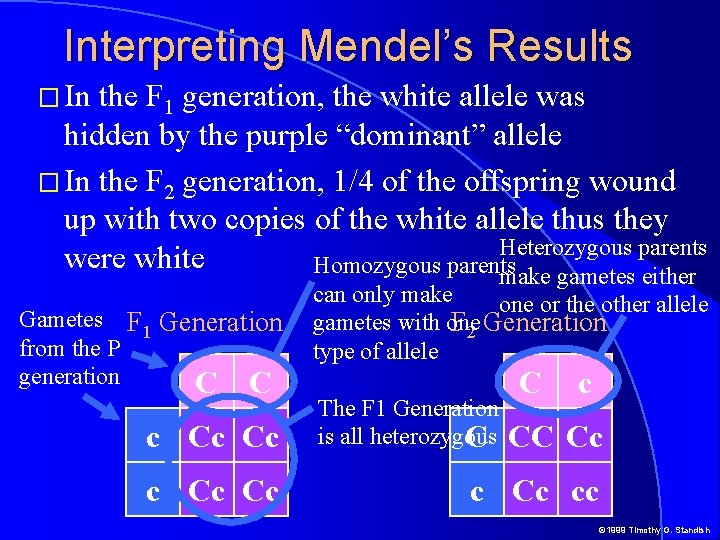

Interpreting Mendel’s Results � In the F 1 generation, the white allele was hidden by the purple “dominant” allele � In the F 2 generation, 1/4 of the offspring wound up with two copies of the white allele thus they Heterozygous parents were white Homozygous parents make gametes either Gametes F 1 Generation from the P generation C C c Cc Cc can only make one or the other allele gametes with one F 2 Generation type of allele The F 1 Generation is all heterozygous C C c CC Cc cc © 1999 Timothy G. Standish

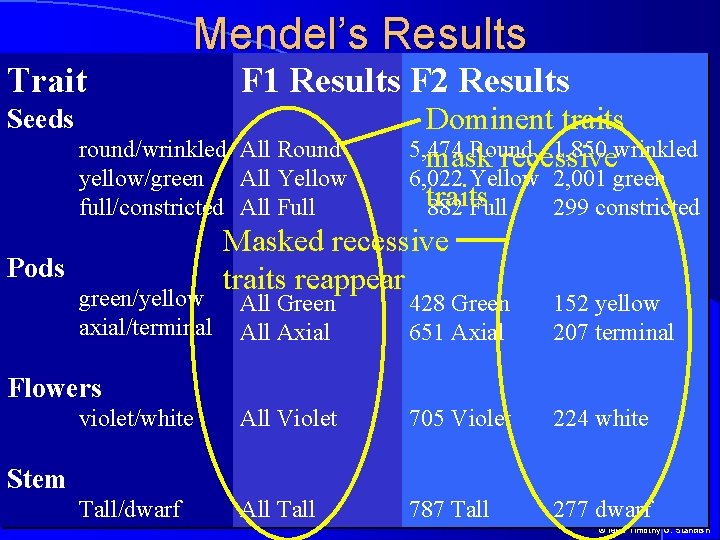

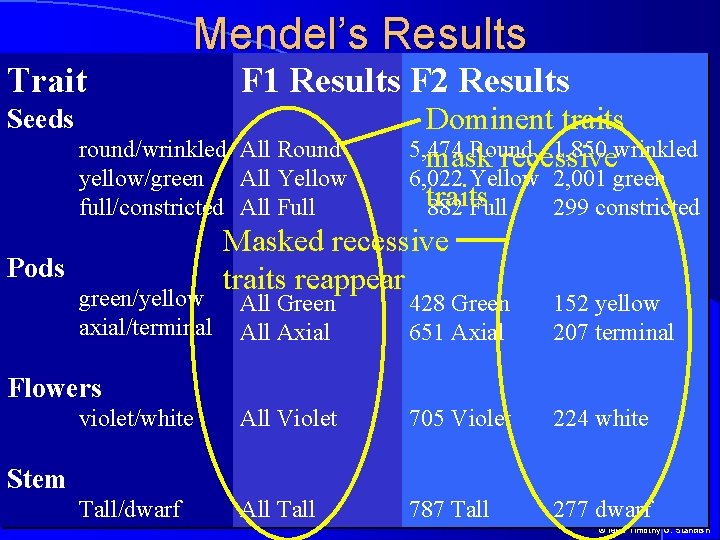

Trait Mendel’s Results F 1 Results F 2 Results Dominent traits round/wrinkled All Round 5, 474 Round 1, 850 wrinkled mask recessive yellow/green All Yellow 6, 022 Yellow 2, 001 green traits full/constricted All Full 882 Full 299 constricted Masked recessive Pods traits reappear Seeds green/yellow axial/terminal All Green All Axial 428 Green 651 Axial 152 yellow 207 terminal violet/white All Violet 705 Violet 224 white Tall/dwarf All Tall 787 Tall 277 dwarf Flowers Stem © 1999 Timothy G. Standish

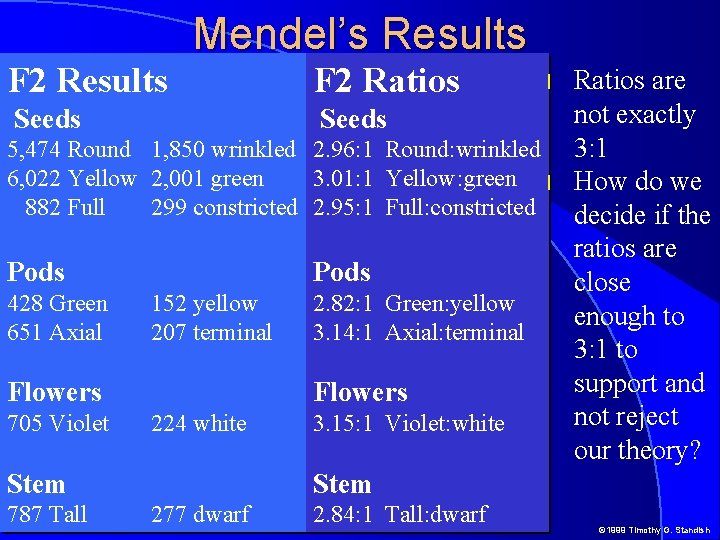

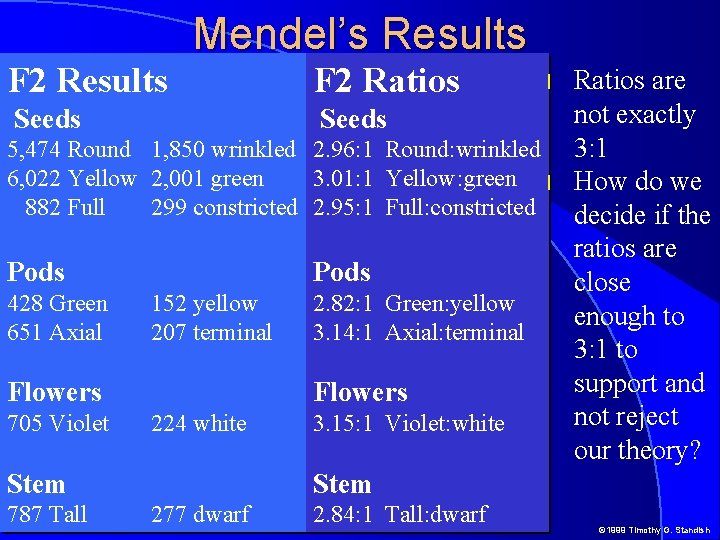

F 2 Results Mendel’s Results Seeds F 2 Ratios l Seeds 5, 474 Round 1, 850 wrinkled 2. 96: 1 Round: wrinkled 6, 022 Yellow 2, 001 green 3. 01: 1 Yellow: green l 882 Full 299 constricted 2. 95: 1 Full: constricted Pods 428 Green 651 Axial Pods 152 yellow 207 terminal Flowers 705 Violet Flowers 224 white Stem 787 Tall 2. 82: 1 Green: yellow 3. 14: 1 Axial: terminal 3. 15: 1 Violet: white Ratios are not exactly 3: 1 How do we decide if the ratios are close enough to 3: 1 to support and not reject our theory? Stem 277 dwarf 2. 84: 1 Tall: dwarf © 1999 Timothy G. Standish

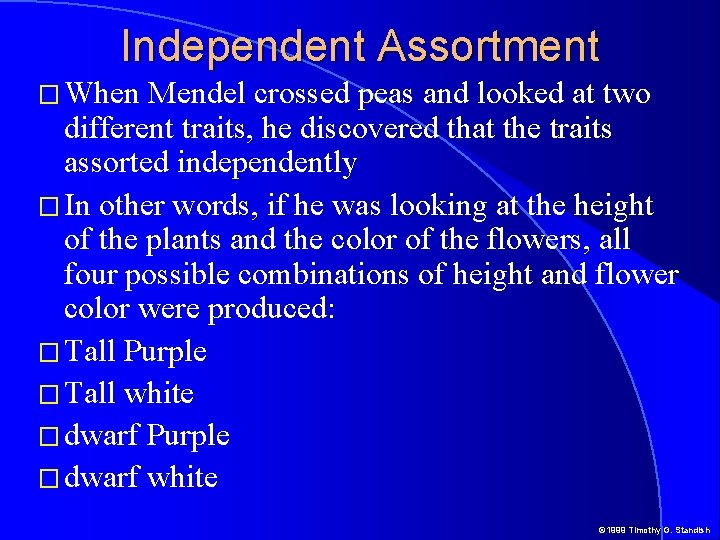

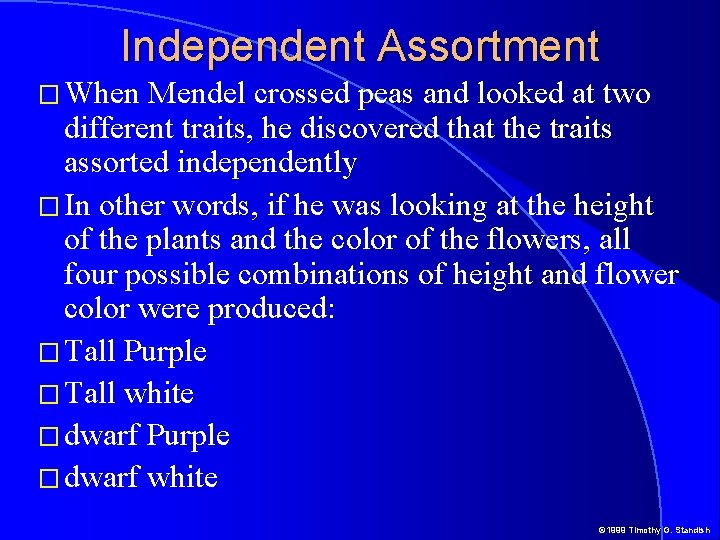

Independent Assortment � When Mendel crossed peas and looked at two different traits, he discovered that the traits assorted independently � In other words, if he was looking at the height of the plants and the color of the flowers, all four possible combinations of height and flower color were produced: � Tall Purple � Tall white � dwarf Purple � dwarf white © 1999 Timothy G. Standish

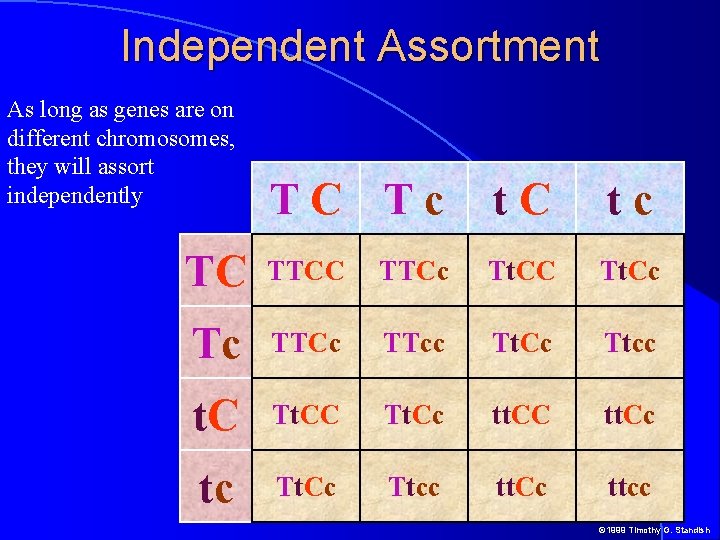

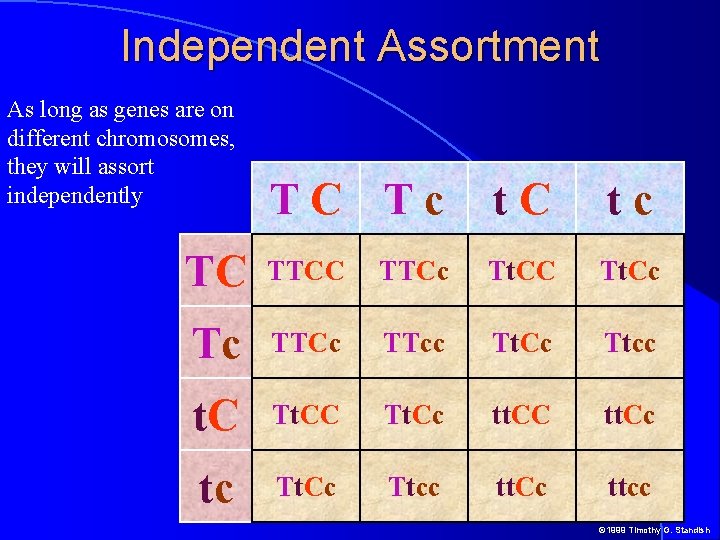

Independent Assortment As long as genes are on different chromosomes, they will assort independently TC Tc t. C tc TC TTCc Tt. CC Tt. Cc Tc TTCc TTcc Tt. Cc Ttcc t. C Tt. Cc tt. CC tt. Cc tc Tt. Cc Ttcc tt. Cc ttcc © 1999 Timothy G. Standish

© 1999 Timothy G. Standish