Graphs 1 a 2 c d 3 e

- Slides: 38

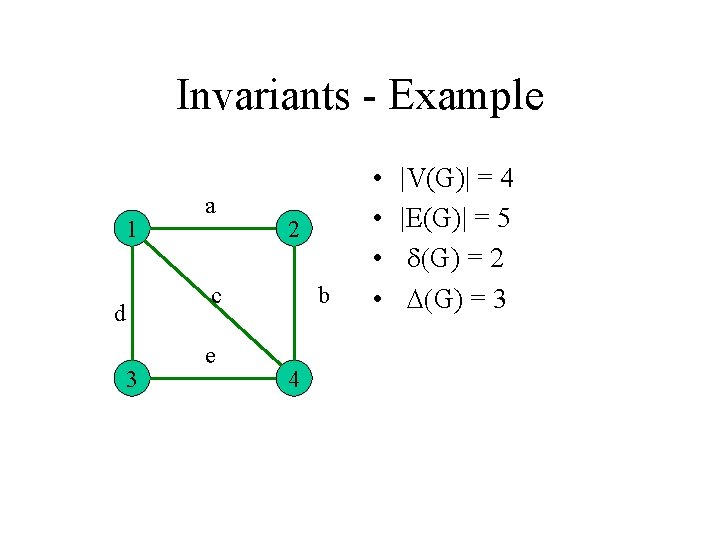

Graphs 1 a 2 c d 3 e b 4 • Simple graph G=(V, E) • V = V(G) ={1, 2, 3, 4} – vertices • E = E(G) = {a, b, c, d, e} – edges • Edge a has endvertices 1 and 2. Vertices 1 and 2 are adjacent: 1 ~ 2.

Simple Graph • Definition: Graph X is composed of the set of vertices V(X) endowed with irreflexive symmetric relation ~ (adjacency). An unoredered pair of adjacent vertices uv = vu forms an edge. The set of edges is denoted by E(X). Sometimes we write X = (V, E) or X(V, E).

Families of Graphs

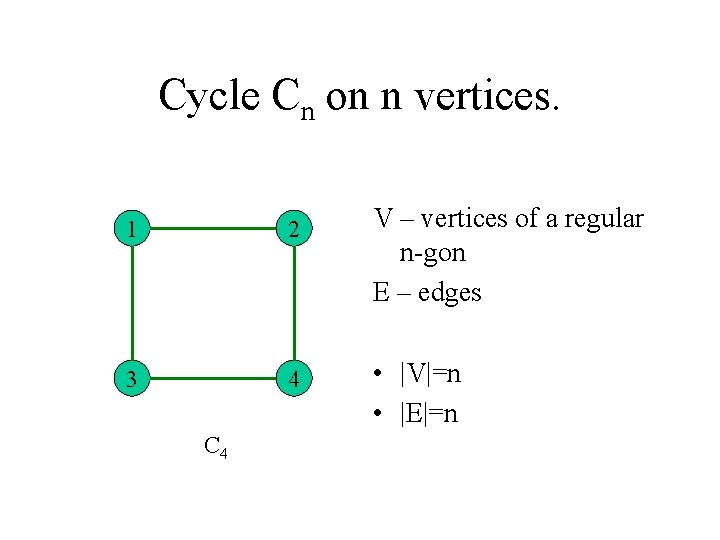

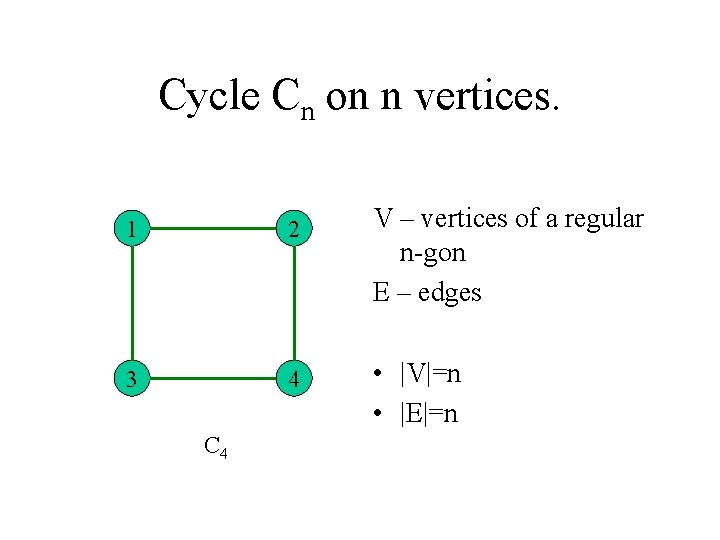

Cycle Cn on n vertices. 1 2 3 4 C 4 V – vertices of a regular n-gon E – edges • |V|=n • |E|=n

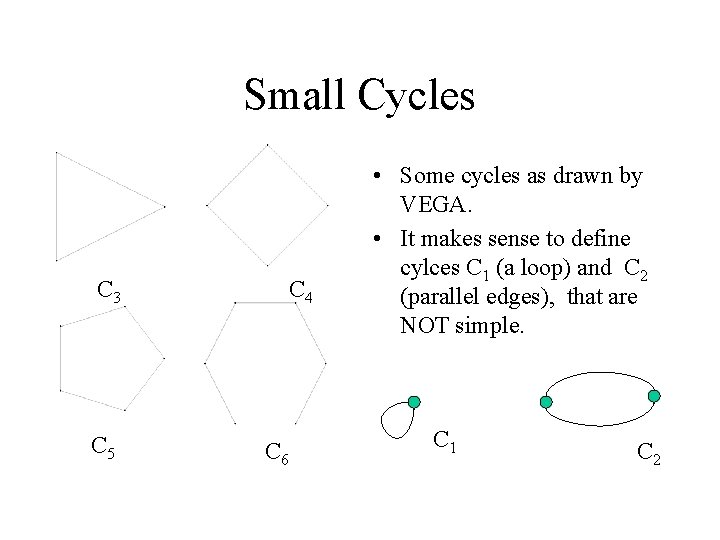

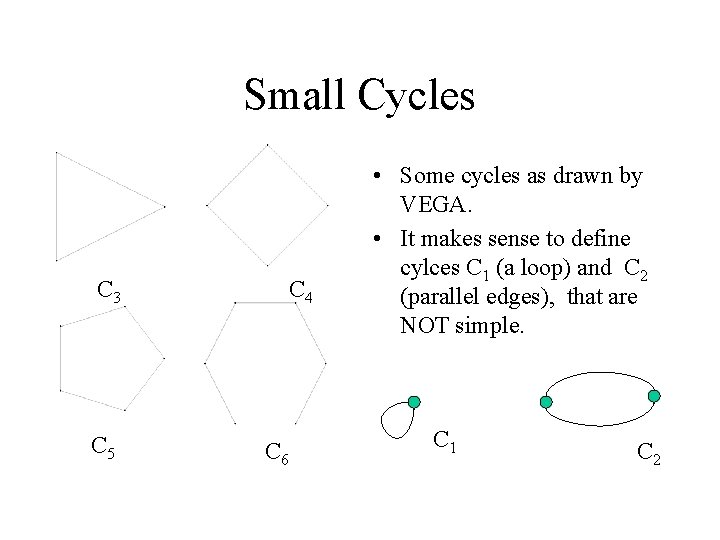

Small Cycles C 3 C 5 C 4 C 6 • Some cycles as drawn by VEGA. • It makes sense to define cylces C 1 (a loop) and C 2 (parallel edges), that are NOT simple. C 1 C 2

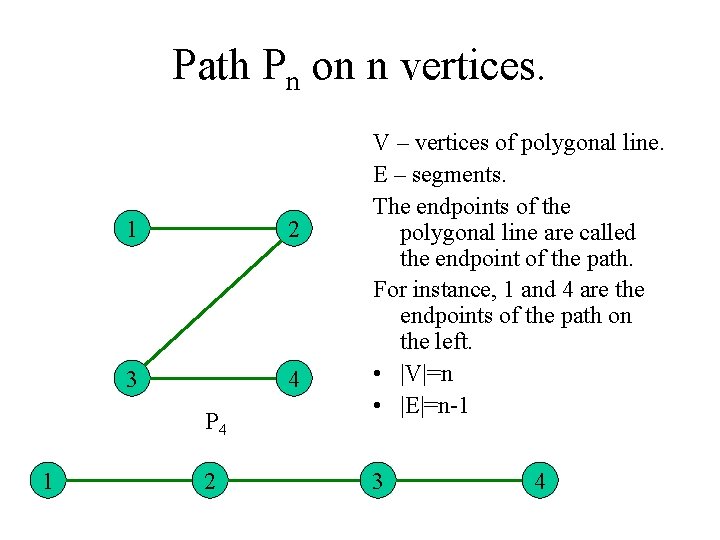

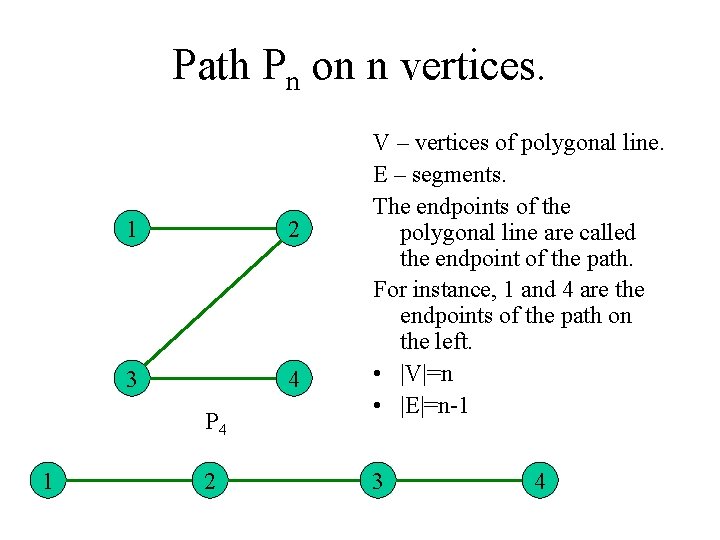

Path Pn on n vertices. 1 2 3 4 P 4 1 2 V – vertices of polygonal line. E – segments. The endpoints of the polygonal line are called the endpoint of the path. For instance, 1 and 4 are the endpoints of the path on the left. • |V|=n • |E|=n-1 3 4

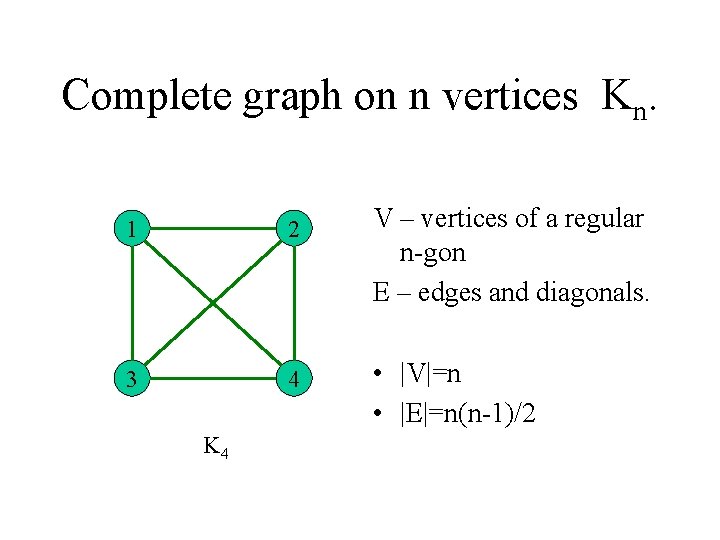

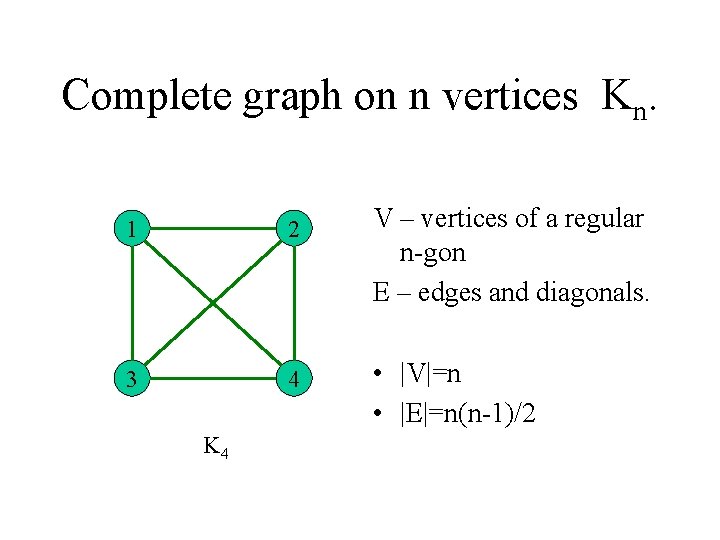

Complete graph on n vertices Kn. 1 2 3 4 K 4 V – vertices of a regular n-gon E – edges and diagonals. • |V|=n • |E|=n(n-1)/2

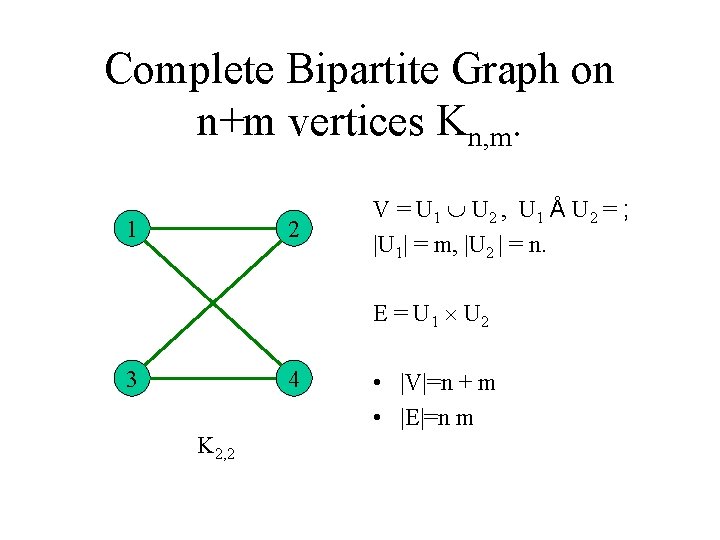

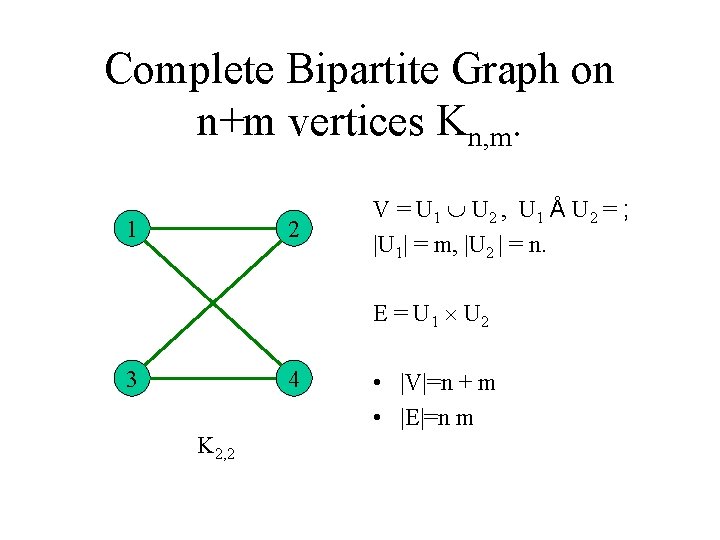

Complete Bipartite Graph on n+m vertices Kn, m. 1 2 V = U 1 U 2 , U 1 Å U 2 = ; |U 1| = m, |U 2 | = n. E = U 1 U 2 3 4 K 2, 2 • |V|=n + m • |E|=n m

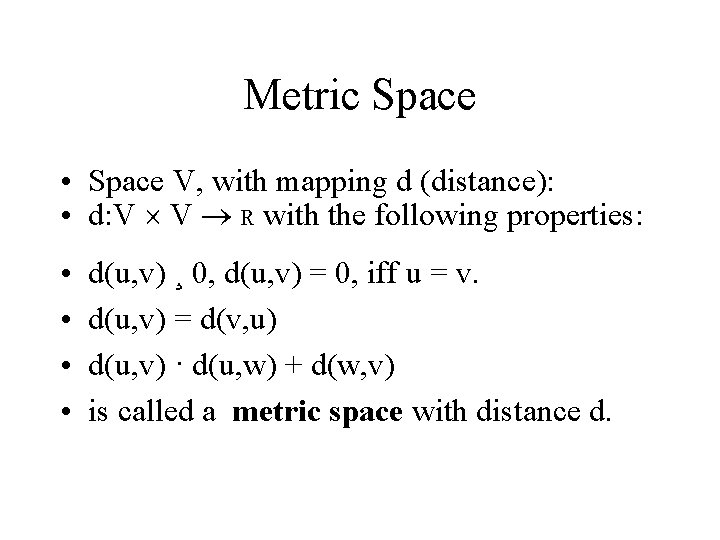

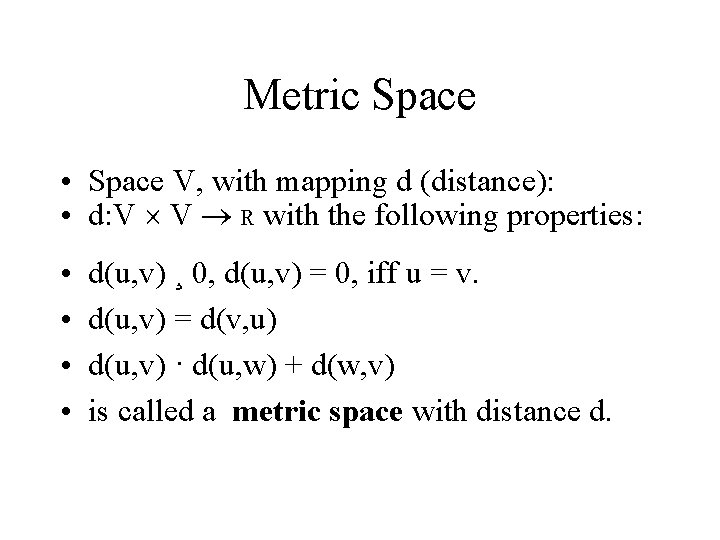

Metric Space • Space V, with mapping d (distance): • d: V V R with the following properties: • • d(u, v) ¸ 0, d(u, v) = 0, iff u = v. d(u, v) = d(v, u) d(u, v) · d(u, w) + d(w, v) is called a metric space with distance d.

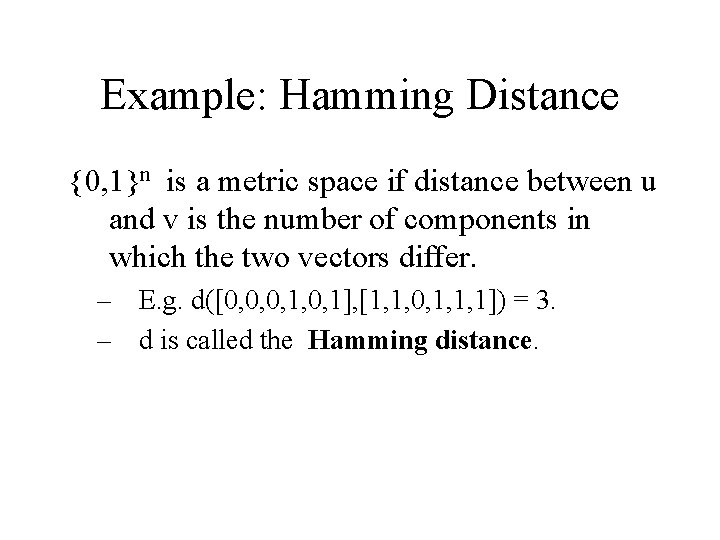

Example: Hamming Distance {0, 1}n is a metric space if distance between u and v is the number of components in which the two vectors differ. – E. g. d([0, 0, 0, 1], [1, 1, 0, 1, 1, 1]) = 3. – d is called the Hamming distance.

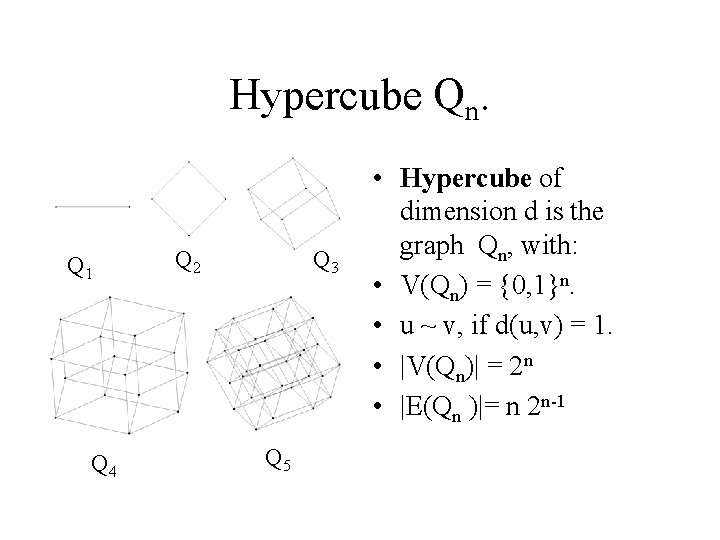

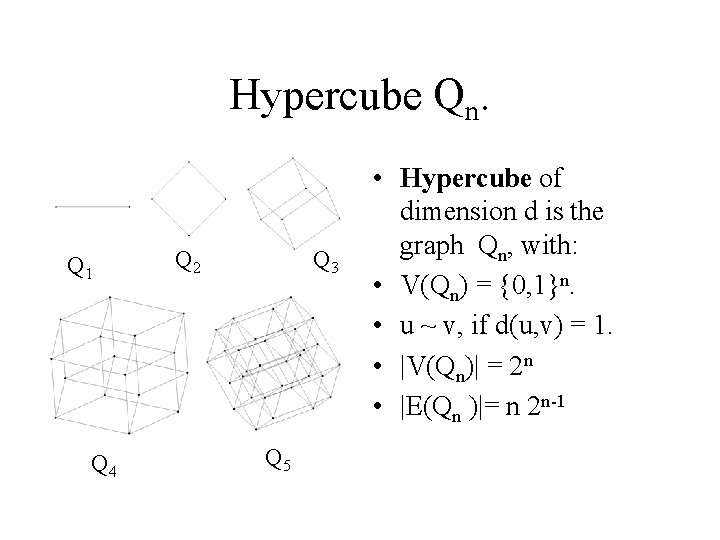

Hypercube Qn. Q 1 Q 4 Q 2 Q 3 Q 5 • Hypercube of dimension d is the graph Qn, with: • V(Qn) = {0, 1}n. • u ~ v, if d(u, v) = 1. • |V(Qn)| = 2 n • |E(Qn )|= n 2 n-1

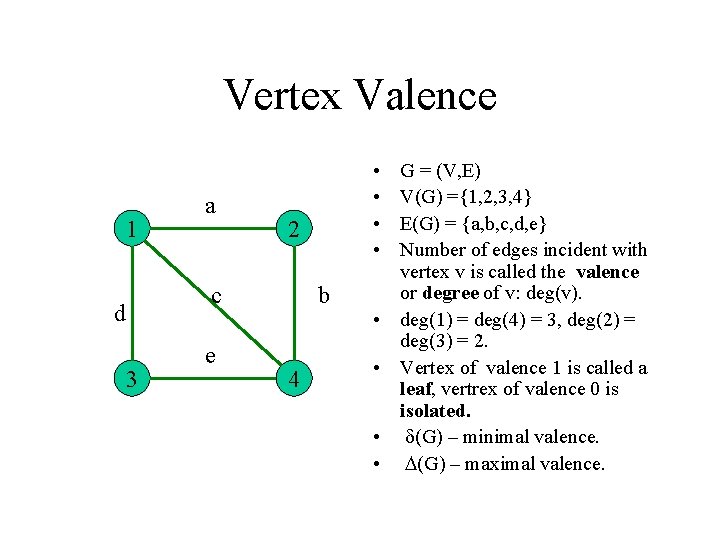

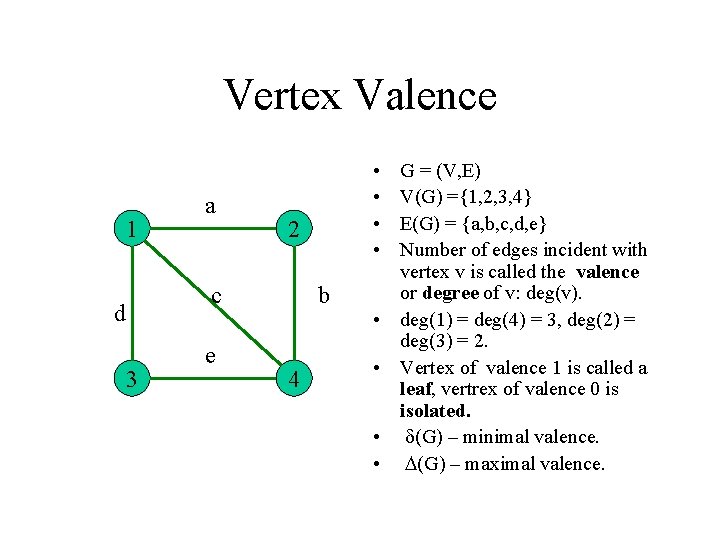

Vertex Valence 1 a 2 c d 3 e • • b 4 • • G = (V, E) V(G) ={1, 2, 3, 4} E(G) = {a, b, c, d, e} Number of edges incident with vertex v is called the valence or degree of v: deg(v). deg(1) = deg(4) = 3, deg(2) = deg(3) = 2. Vertex of valence 1 is called a leaf, vertrex of valence 0 is isolated. d(G) – minimal valence. D(G) – maximal valence.

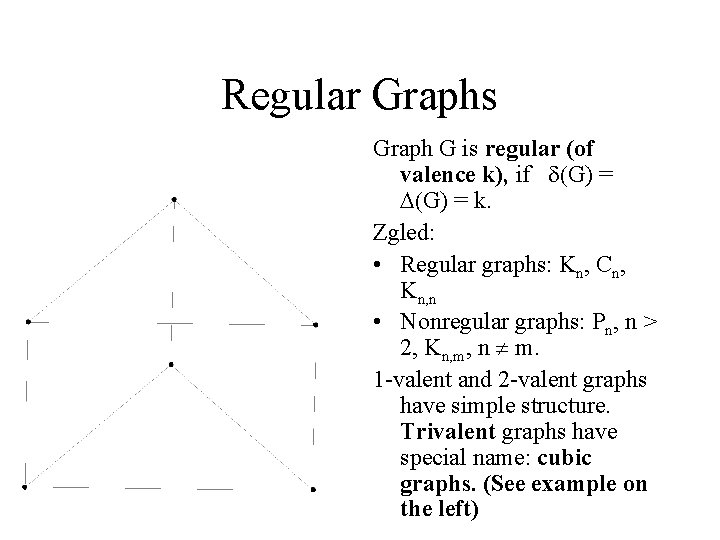

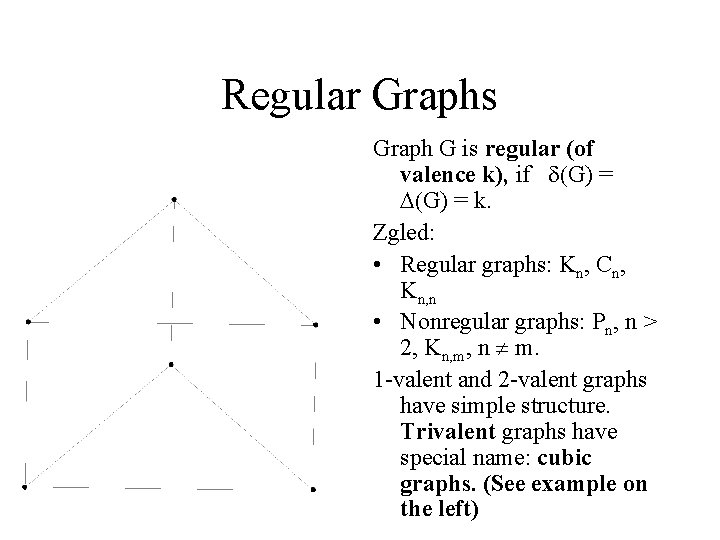

Regular Graphs Graph G is regular (of valence k), if d(G) = D(G) = k. Zgled: • Regular graphs: Kn, Cn, Kn, n • Nonregular graphs: Pn, n > 2, Kn, m, n ¹ m. 1 -valent and 2 -valent graphs have simple structure. Trivalent graphs have special name: cubic graphs. (See example on the left)

Girth • Girth g(G) of graph G is the number of vertices of the shortest cycle in G. If G has no cycles, its girth is infinite.

Cages • Graph G is a g-cage, if the following holds: 1. Trivalent 2. Has girth g 3. Has the least number of vertices among the graphs satisfying 1 and 2.

Exercises 01 • • N 1. Deterimine the 3 -cage. N 2. Determine the 4 -cage. N 3. Determine the 5 -cage. N 4. Determine the 6 -cage.

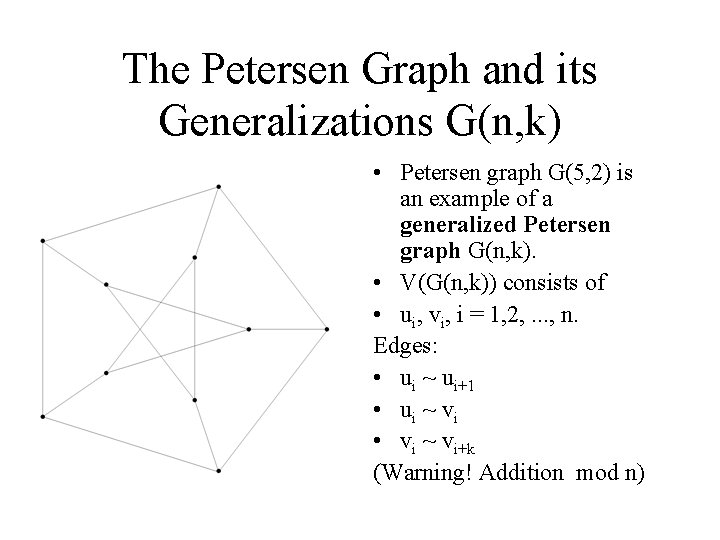

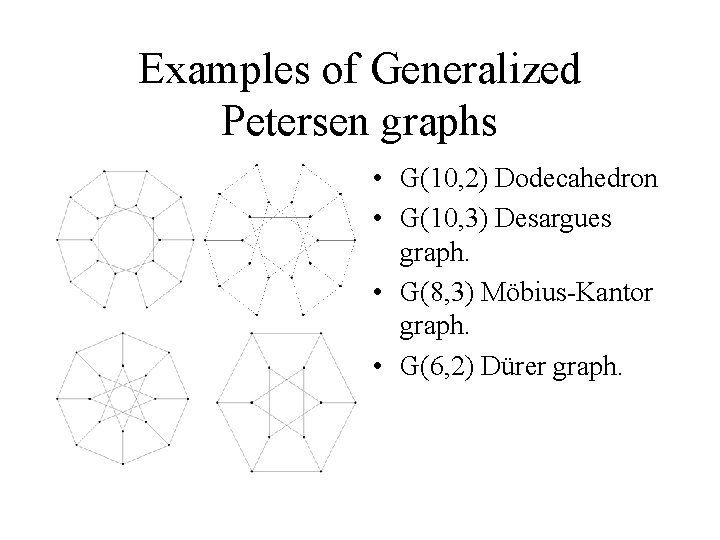

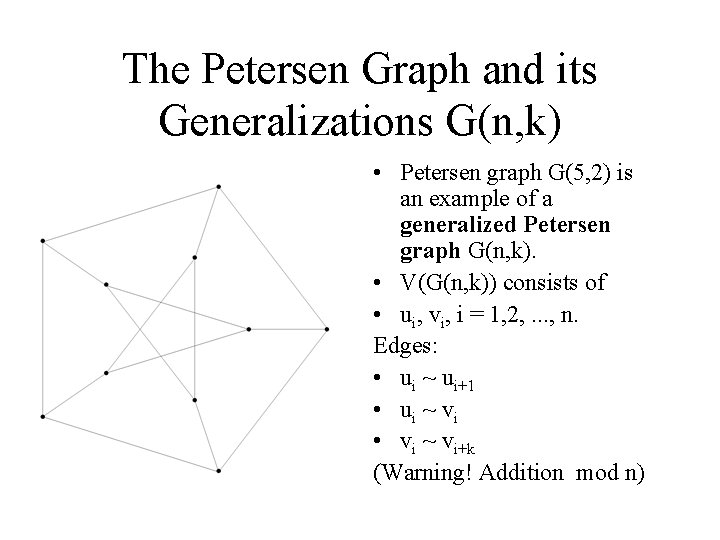

The Petersen Graph and its Generalizations G(n, k) • Petersen graph G(5, 2) is an example of a generalized Petersen graph G(n, k). • V(G(n, k)) consists of • ui, vi, i = 1, 2, . . . , n. Edges: • ui ~ ui+1 • ui ~ vi • vi ~ vi+k (Warning! Addition mod n)

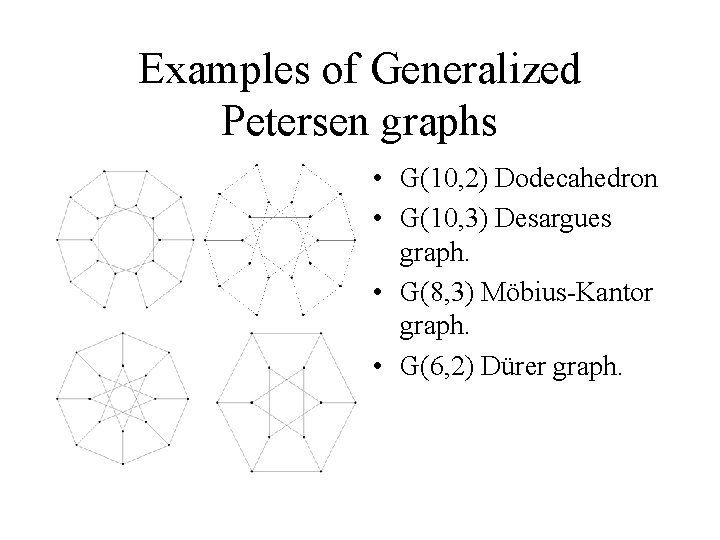

Examples of Generalized Petersen graphs • G(10, 2) Dodecahedron • G(10, 3) Desargues graph. • G(8, 3) Möbius-Kantor graph. • G(6, 2) Dürer graph.

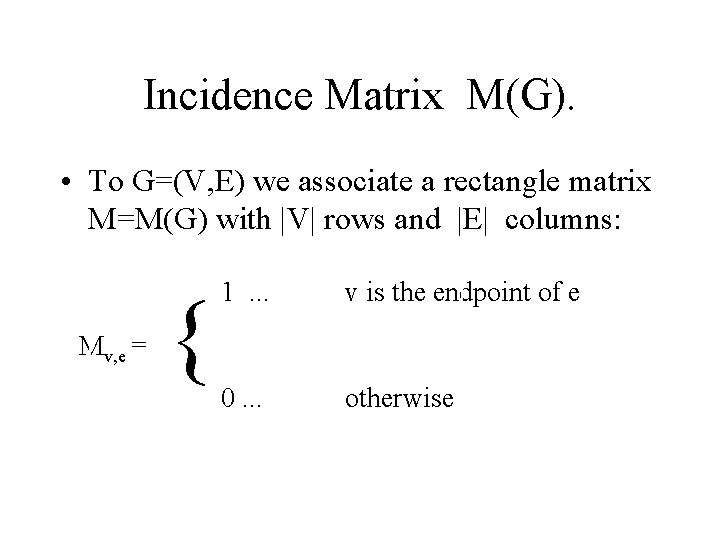

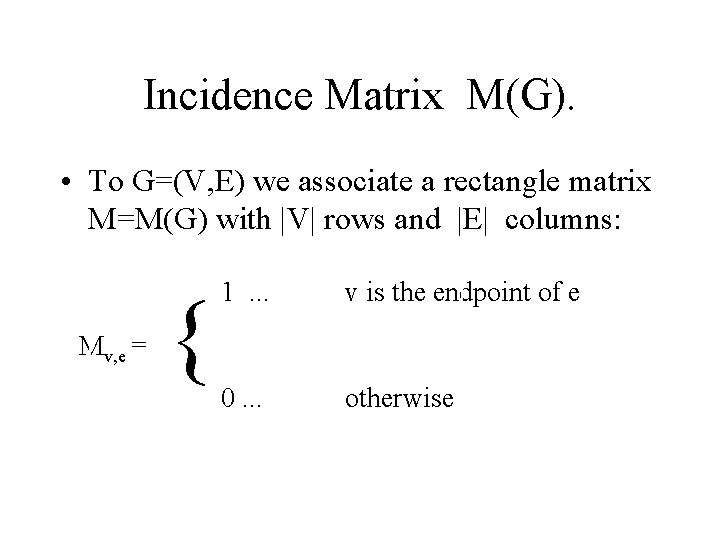

Incidence Matrix M(G). • To G=(V, E) we associate a rectangle matrix M=M(G) with |V| rows and |E| columns: Mv, e = { 1. . . v is the endpoint of e 0. . . otherwise

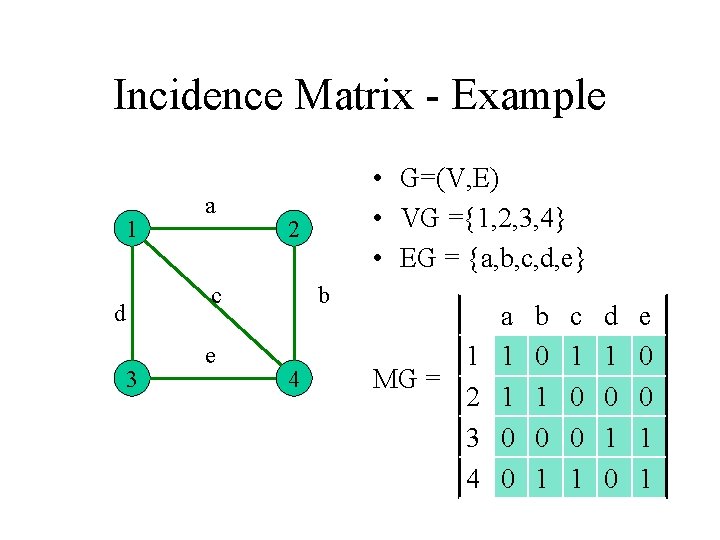

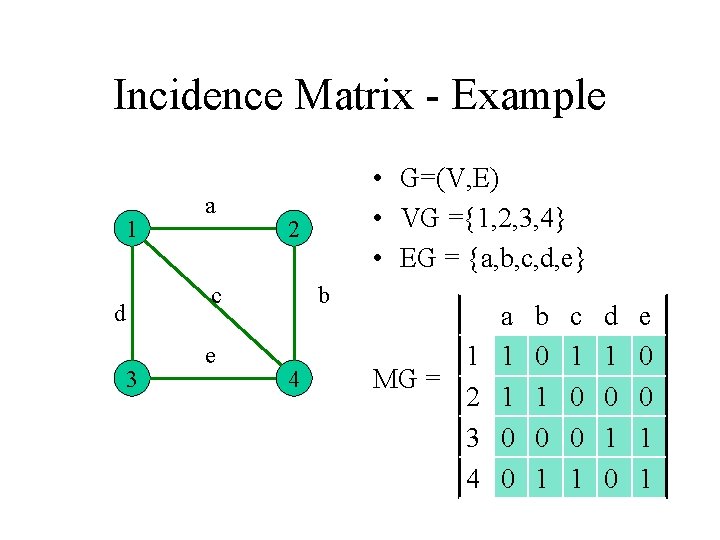

Incidence Matrix - Example 1 a 2 c d 3 e • G=(V, E) • VG ={1, 2, 3, 4} • EG = {a, b, c, d, e} b 4 1 MG = 2 3 4 a 1 1 0 0 b 0 1 c 1 0 0 1 d 1 0 e 0 0 1 1

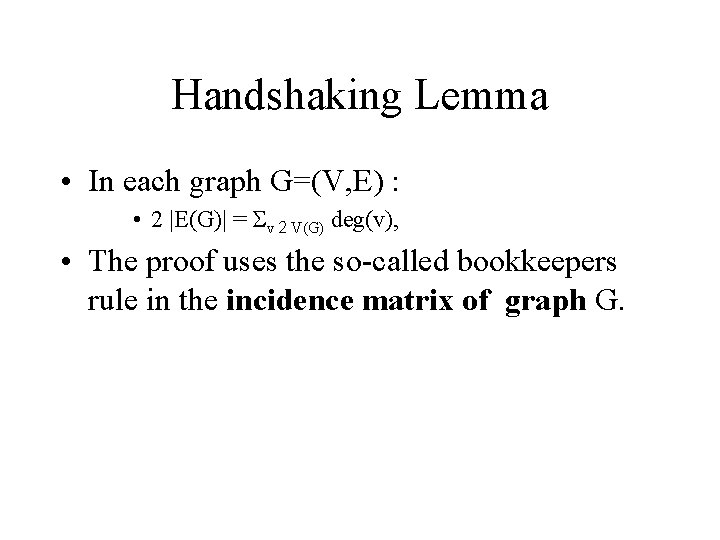

Handshaking Lemma • In each graph G=(V, E) : • 2 |E(G)| = Sv 2 V(G) deg(v), • The proof uses the so-called bookkeepers rule in the incidence matrix of graph G.

Graph Invariant • It is well-known that we associate numbers to mathematical objects in various ways. For instance: Determinant is assicated to a matrix, degree is associated to a polynomial, dimension is associated to a space, length is associated to a vector, etc. • There are several numbers that can be associated with a graph. Such a number is usually called graph invariant. One may argue that the main topic of graph theory is the study of graph invariants. • In addition to numbers other objects may be graph invariants.

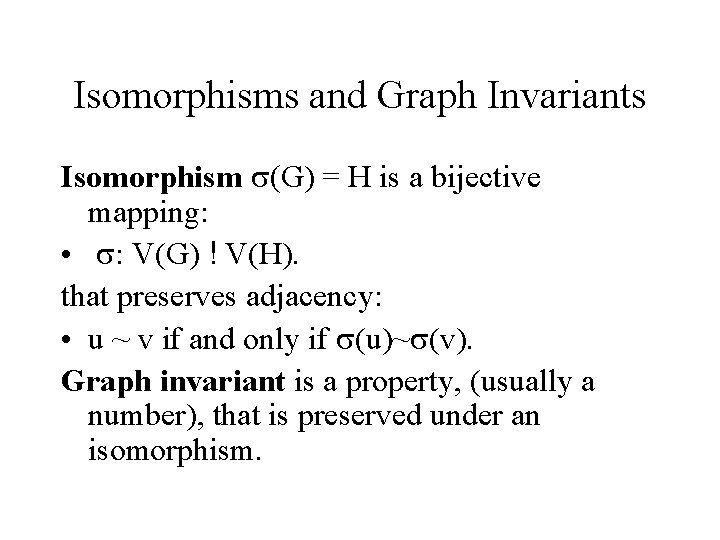

Isomorphisms and Graph Invariants Isomorphism s(G) = H is a bijective mapping: • s: V(G) ! V(H). that preserves adjacency: • u ~ v if and only if s(u)~s(v). Graph invariant is a property, (usually a number), that is preserved under an isomorphism.

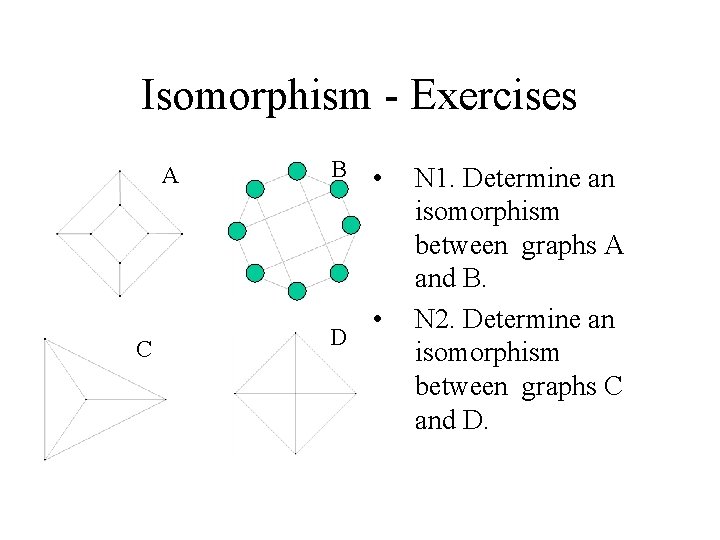

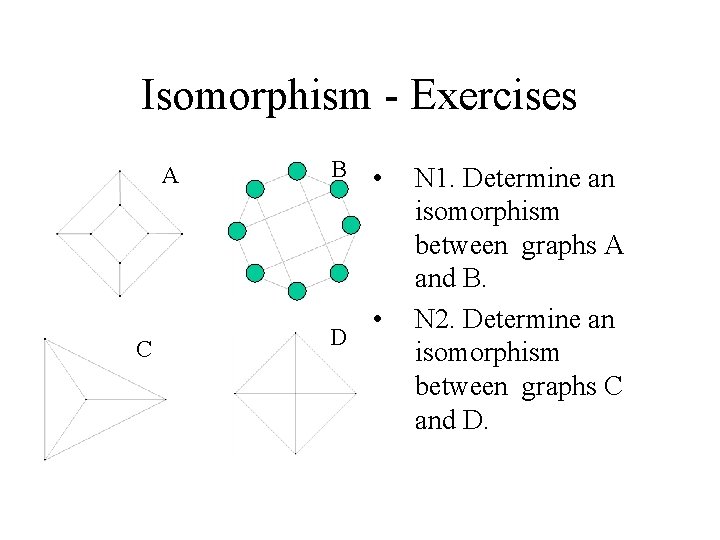

Isomorphism - Exercises A C B D • • N 1. Determine an isomorphism between graphs A and B. N 2. Determine an isomorphism between graphs C and D.

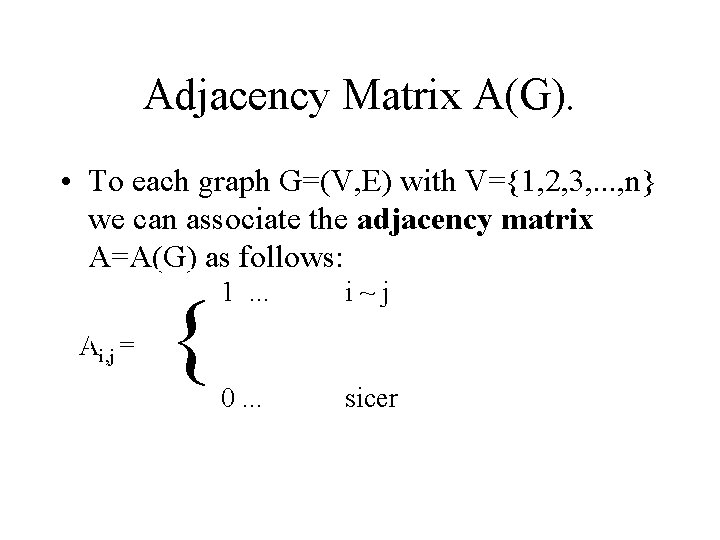

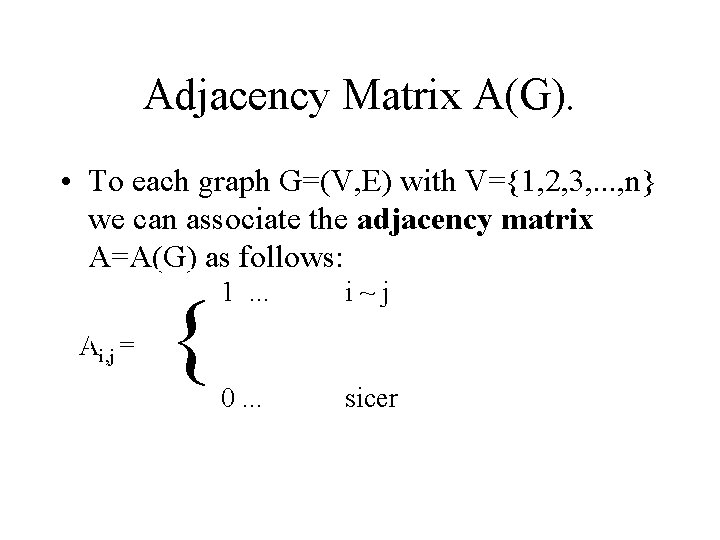

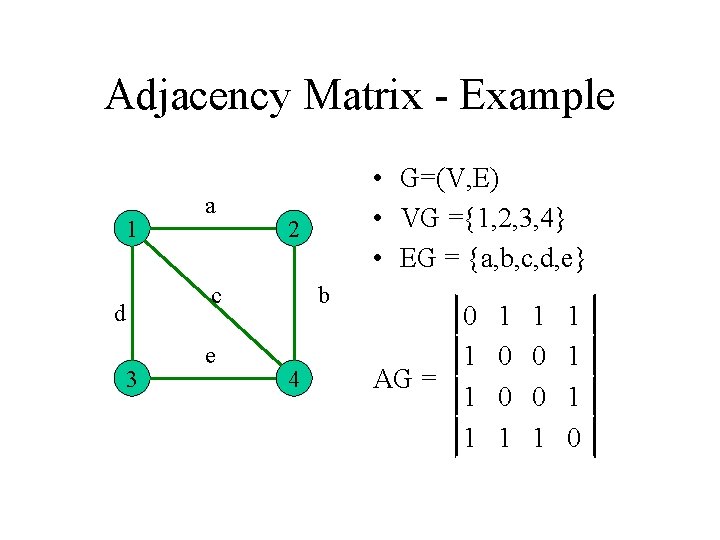

Adjacency Matrix A(G). • To each graph G=(V, E) with V={1, 2, 3, . . . , n} we can associate the adjacency matrix A=A(G) as follows: Ai, j = { 1. . . i~j 0. . . sicer

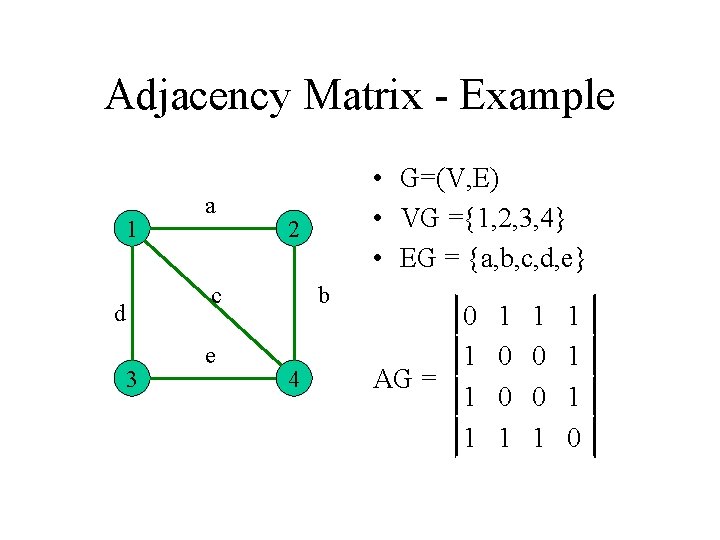

Adjacency Matrix - Example 1 a 2 c d 3 e • G=(V, E) • VG ={1, 2, 3, 4} • EG = {a, b, c, d, e} b 4 0 1 AG = 1 1 1 0 0 1 1 0

Adjacency Matrix is Not an Invariant • Adajcency matrix is not an invariant. It depends on the numbering of vertices. • Incidence matrix is not an invariant

Some Graph Invariants • • |V(G)| = number of vertices |E(G)| = number of edges d(G) = minimal valence. D(G) = maximal valence

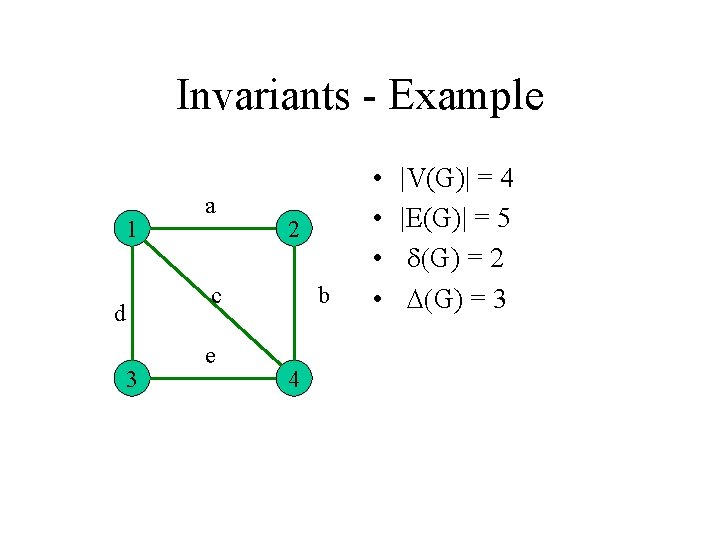

Invariants - Example 1 a 2 c d 3 e b 4 • • |V(G)| = 4 |E(G)| = 5 d(G) = 2 D(G) = 3

Trees • A tree is a connected graph with no cycles • There are several characterizations of tree, such as: • A tree is a connected graph with n vertices and n-1 edges. • A tree is a connected graph that is no longer connected after removal of any edge.

Disjoint Union of Sets • Let A and B be sets. By A t B we denote the disjoiont union of A and B. If A Å B = ; , then A t B is simply the union of the two sets. Otherwise we defne formally A t B = A £ {0} [ B £ {1}.

Disjoint Union of Graphs • Let G’ and G” be graphs. By G’ t G” we denote the disjoiont union of graphs G’ and G”. This means • V(G’ t G”) : = V(G’) t V(G”) and • E(G’ t G”) : = E(G’) t E(G”).

The Empty Graph • Empty graph f = (f, f) has no vertices and no edges.

Connectivity in Graphs - Theory • Graph G is connected, if and only if it cannot be written as a disjoint union of two non-empty graphs.

Connectivity of Graphs - Practice • Graph is connected, if we grab and shake the “model” made of balls and strings, and nothing falls down the earth. (No knotting of strings is permitted!)

Equivalence Relation @. • Let G be a graph. On V(G) define @ as follows: For any u, v 2 V(G) let u @ v, if and only if there exists a subgraph, isomorphic to a path that has the endponts u and v. • Proposition. @ is an equivlanece relation on V(G). • Proof. Obviously reflexive and symmetric. Proof of transitivity – Homework.

Path Connectivity of Graphs • G is connected by paths, if the equivalence relation @ has a single equivalence class.

Homework • H 1: Prove that the relation @ is transitive. • H 2: Prove that for finite graphs the notions of connectedness and path connectedness coincide.