Grammar and meaning Symposium for ALevel Teachers of

- Slides: 25

Grammar and meaning Symposium for A-Level Teachers of English Language Monday 26 th June 2017 Dr Louise Nuttall Lecturer in Stylistics l. nuttall@hud. ac. uk Twitter: @Louise. Nuttall

TALK OUTLINE 1) Grammar and meaning in stylistics àForegrounding, deviation and parallelism 2) Grammar and meaning in cognitive linguistics àFigure and ground 3) Language as representation

GRAMMAR & MEANING IN STYLISTICS ‘Stylistics is an approach to reading and analysing texts that concentrates on the relationships between language and interpretative effects’ (Macrae 2016: 51) ‘stylistic interpretation involves a process of making equations between, or inferences about, linguistic forms and the meaning contracted by the function or operation of these forms in a literary context. (Carter The whole 1997: issue 200) of precisely what is involved in this is very complex and stylisticians are committed to debates over what goes on in the process and how particular interpretative facts can be established on a verifiable basis. ’ (Carter 1997: 200)

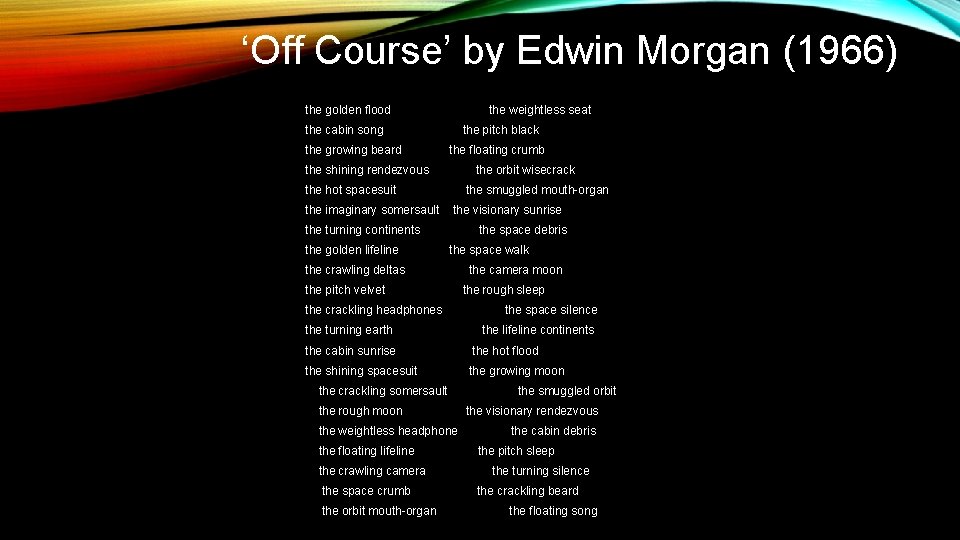

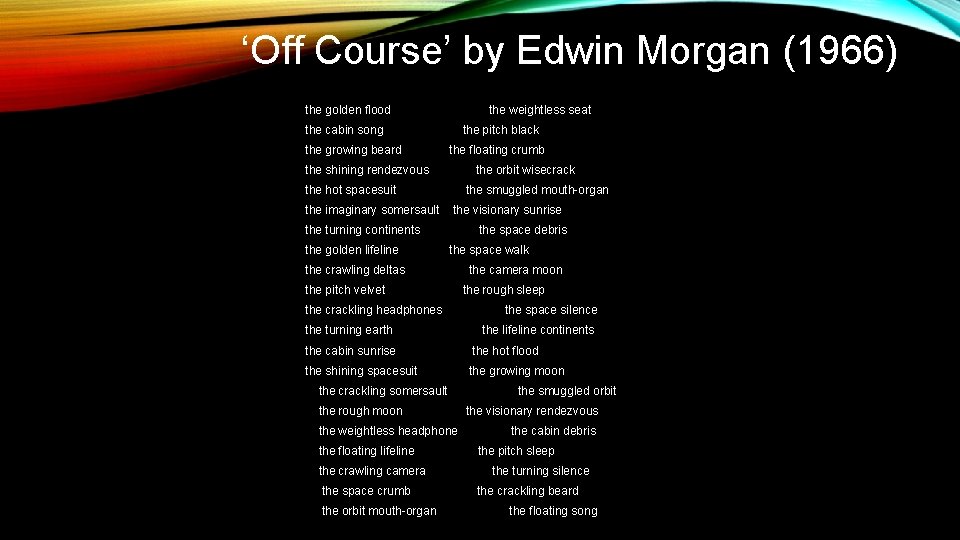

‘Off Course’ by Edwin Morgan (1966) the golden flood the weightless seat the cabin song the growing beard the pitch black the floating crumb the shining rendezvous the orbit wisecrack the hot spacesuit the imaginary somersault the smuggled mouth-organ the visionary sunrise the turning continents the golden lifeline the space debris the space walk the crawling deltas the pitch velvet the crackling headphones the turning earth the camera moon the rough sleep the space silence the lifeline continents the cabin sunrise the hot flood the shining spacesuit the growing moon the crackling somersault the rough moon the weightless headphone the floating lifeline the crawling camera the space crumb the orbit mouth-organ the smuggled orbit the visionary rendezvous the cabin debris the pitch sleep the turning silence the crackling beard the floating song

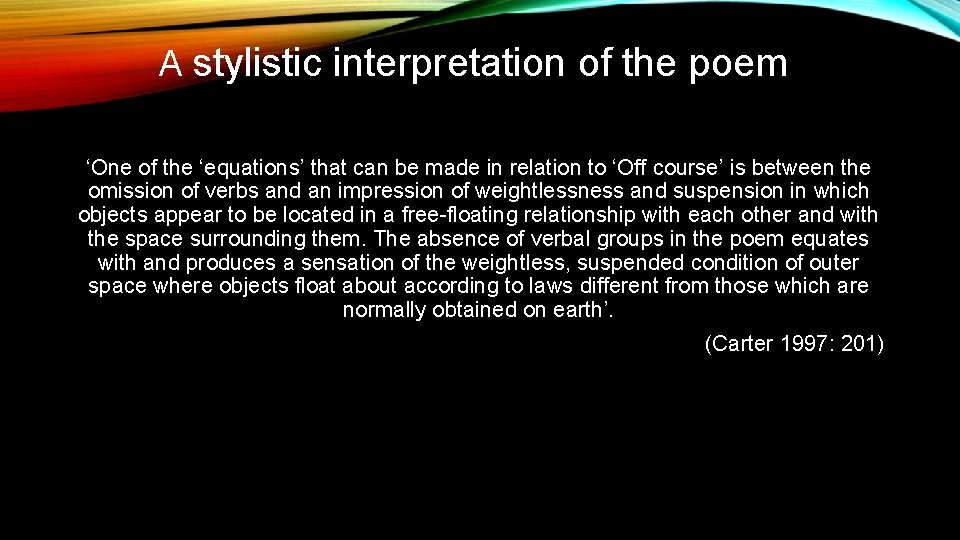

A stylistic interpretation of the poem ‘One of the ‘equations’ that can be made in relation to ‘Off course’ is between the omission of verbs and an impression of weightlessness and suspension in which objects appear to be located in a free-floating relationship with each other and with the space surrounding them. The absence of verbal groups in the poem equates with and produces a sensation of the weightless, suspended condition of outer space where objects float about according to laws different from those which are normally obtained on earth’. (Carter 1997: 201)

FOREGROUNDING Linguistic choices which stand out in some way, or are made prominent in attention (Mukařovský 1964) Leech (1970) ‘Cohesion of foregrounding’: • Foregrounded linguistic choices prompt us to look for meaning which connects and explains them cohesively.

FOREGROUNDING TECHNIQUES • Parallelism: the creation of a noticeable pattern through repetition. • Deviation: departure from a norm or convention. o External deviation: departure from a norm external to the text (e. g. Standard English grammar, spelling, genre conventions, register etc). o Internal deviation: departure from a norm set up within the text itself (e. g. a repeated sentence structure, a rhyme scheme).

FOREGROUNDING AND LANGUAGE LEVELS Foregrounding (through parallelism or deviation) can occur at any level of language: • • • Phonetics, phonology and prosodics Graphology Grammar, including syntax and morphology Lexis and semantics Pragmatics Discourse

FOREGROUNDING AT THE LEVEL OF GRAMMAR TV advert for Royal Navy recruitment (2013)

FOREGROUNDING ANALYSIS You’re born. You cry. You grow. You learn. You change. You pull. You push. You pause. You think. You start. You learn. You fly. You chase. You fly. You save. You meet. You greet. You hush. You go. You chase. You click. You pull. You pause. You help rise find hunt save shout shoot learn live. A life without limits. Search navy jobs online. short, simple sentences; second person pronoun No objects for verbs (transitive and intransitive) Patterns = Parallelism (and external deviation from SE) Break in these patterns at the end = Internal deviation

TEXT ALTERATION “She screamed then, and Lennie’s other hand closed over her mouth and nose. ” (John Steinbeck, Of Mice and Men) • She screamed then, and Lennie closed his other hand over her mouth and nose. • She screamed then. Lennie closed his other hand over her mouth and nose.

GRAMMAR AND MEANING IN COGNITIVE LINGUISTICS 1) Grammar is meaningful ‘Not only is it meaningful, it also reflects our basic experience of moving, perceiving and acting on the world. At the core of grammatical meanings are mental operations inherent in these elemental components of moment-to-moment living’ (Langacker 2008: 4). 2) Grammatical choices represent individual ‘construals’ of a situation ‘In viewing a scene, what we actually see depends on how closely we examine it, what we choose to look at, which elements we pay most attention to, and where we view it from. The corresponding labels I will use, for broad classes of construal phenomena, are specificity, focusing, prominence, and perspective’. (Langacker 2008: 55)

GRAMMAR AND MEANING IN COGNITIVE LINGUISTICS 1) Grammar is meaningful ‘Not only is it meaningful, it also reflects our basic experience of moving, perceiving and acting on the world. At the core of grammatical meanings are mental operations inherent in these elemental components of moment-to-moment living’ (Langacker 2008: 4). 2) Grammatical choices represent individual ‘construals’ of a situation: ‘In viewing a scene, what we actually see depends on how closely we examine it, what we choose to look at, which elements we pay most attention to, and where we view it from. The corresponding labels I will use, for broad classes of construal phenomena, are specificity, focusing, prominence, and perspective’. (Langacker 2008: 55)

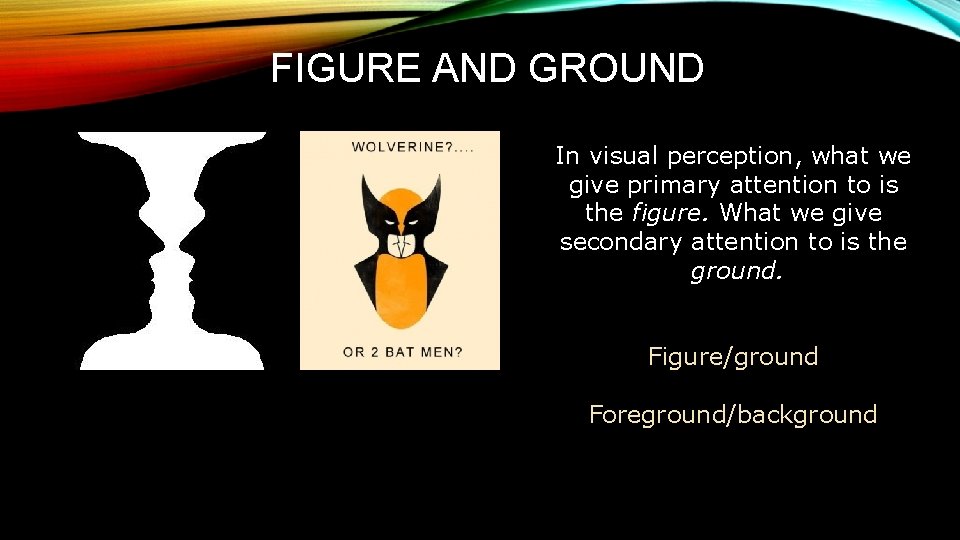

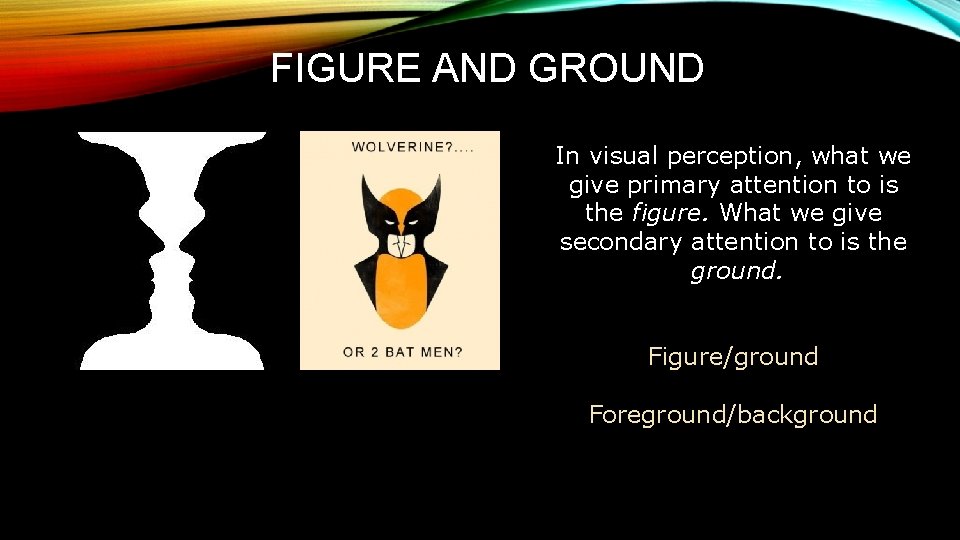

FIGURE AND GROUND In visual perception, what we give primary attention to is the figure. What we give secondary attention to is the ground. Figure/ground Foreground/background

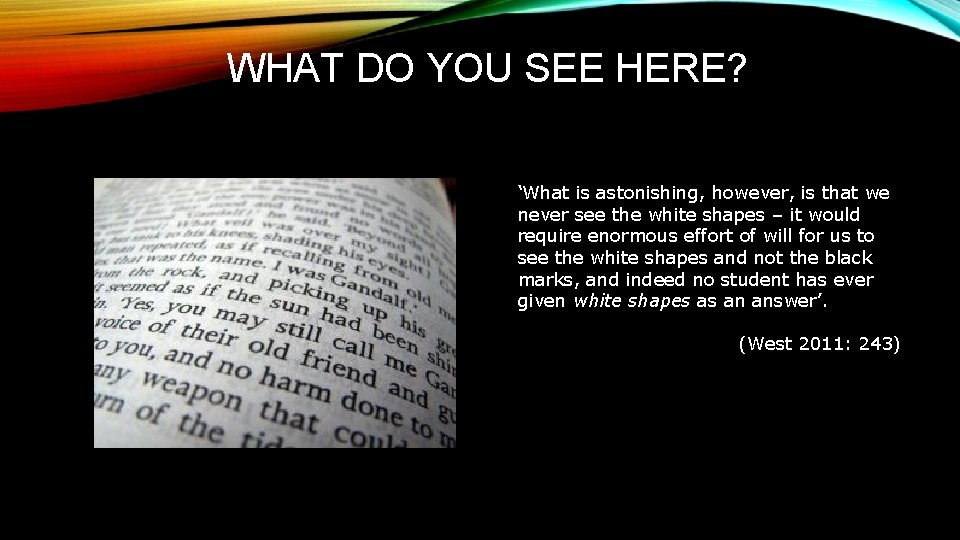

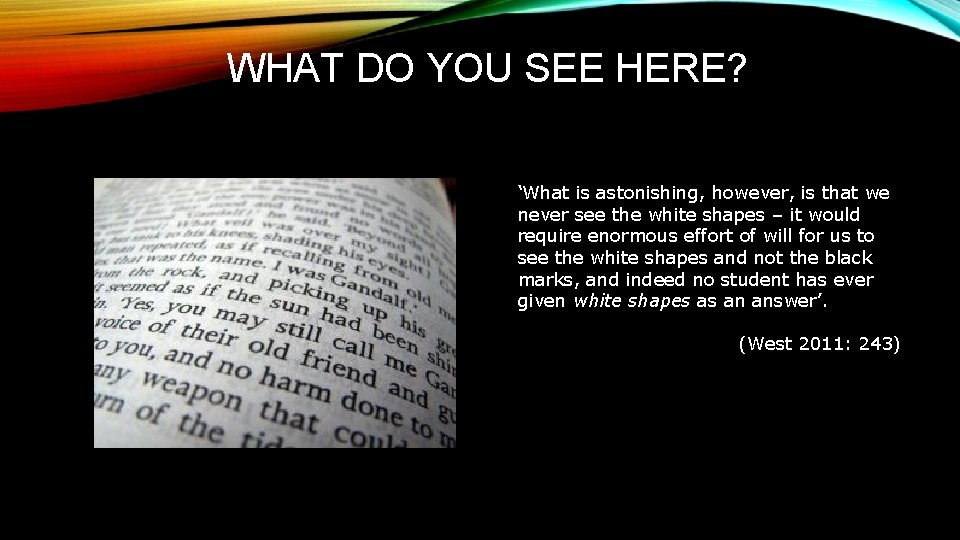

WHAT DO YOU SEE HERE? ‘What is astonishing, however, is that we never see the white shapes – it would require enormous effort of will for us to see the white shapes and not the black marks, and indeed no student has ever given white shapes as an answer’. (West 2011: 243)

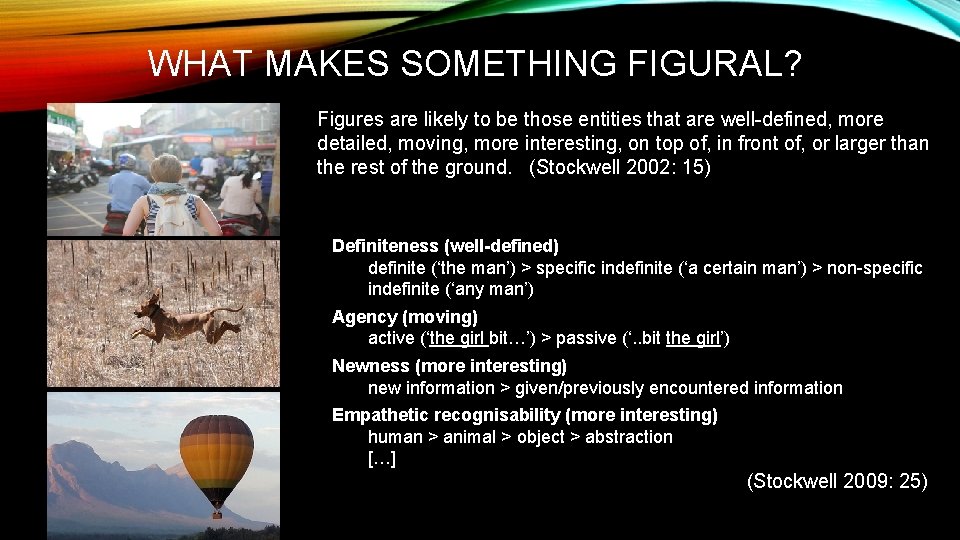

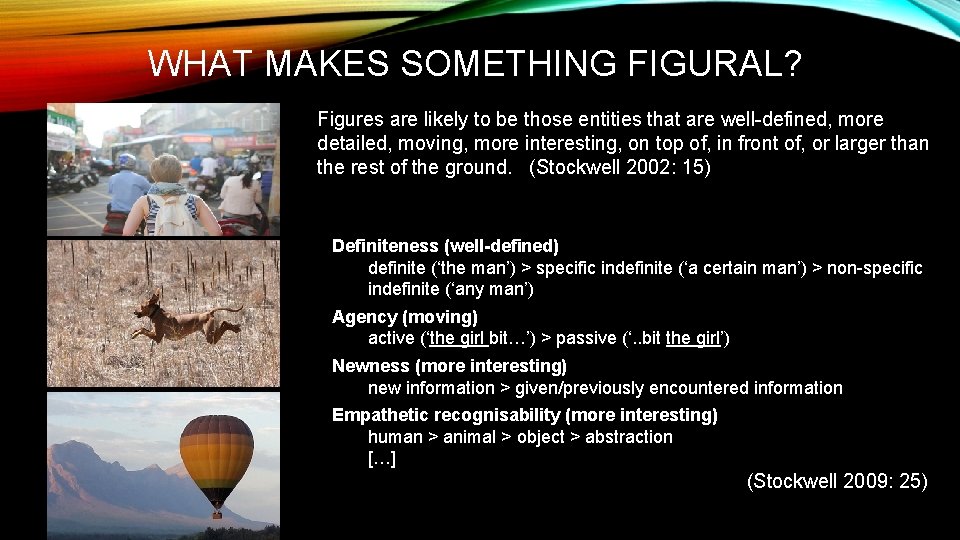

WHAT MAKES SOMETHING FIGURAL? Figures are likely to be those entities that are well-defined, more detailed, moving, more interesting, on top of, in front of, or larger than the rest of the ground. (Stockwell 2002: 15) Definiteness (well-defined) definite (‘the man’) > specific indefinite (‘a certain man’) > non-specific indefinite (‘any man’) Agency (moving) active (‘the girl bit…’) > passive (‘. . bit the girl’) Newness (more interesting) new information > given/previously encountered information Empathetic recognisability (more interesting) human > animal > object > abstraction […] (Stockwell 2009: 25)

FIGURE/GROUND ALIGNMENT AND GRAMMATICALITY Figure and ground can help us to explain why certain grammatical choices seem more intuitively ‘natural’ than others: Figures (i. e. entities that are typically a) well-defined/detailed, b) animate/moving, c) more interesting) typically go in subject position in a clause. 1. 2. 3. 4. The writing on the page …The page under the writing Mary is a doctor. …A doctor is Mary.

FIGURE/GROUND AND FOREGROUNDING Texts that deviate from this norm (e. g. by drawing our attention to something that doesn’t meet this criteria) can create foregrounding effects at the level of grammar: Isn't it rather the garden that quietly crosses the cat? Graffiti on Paris metro (cited in Hamilton 2003))

You’re born. You cry. You grow. You learn. You change. You pull. You push. You pause. You think. You start. You learn. You fly. You chase. You fly. You save. You meet. You greet. You hush. You go. You chase. You click. You pull. You pause. You help rise find hunt save shout shoot learn live. A life without limits. Search navy jobs online. (Royal Navy 2013) A series of very strong figures as subjects (agency, empathetic recognisability), but with no grounds. She screamed then, and Lennie’s other hand closed over her mouth and nose. (Steinbeck, Of Mice and Men) A weak figure as subject (empathetic recognisability – body part)

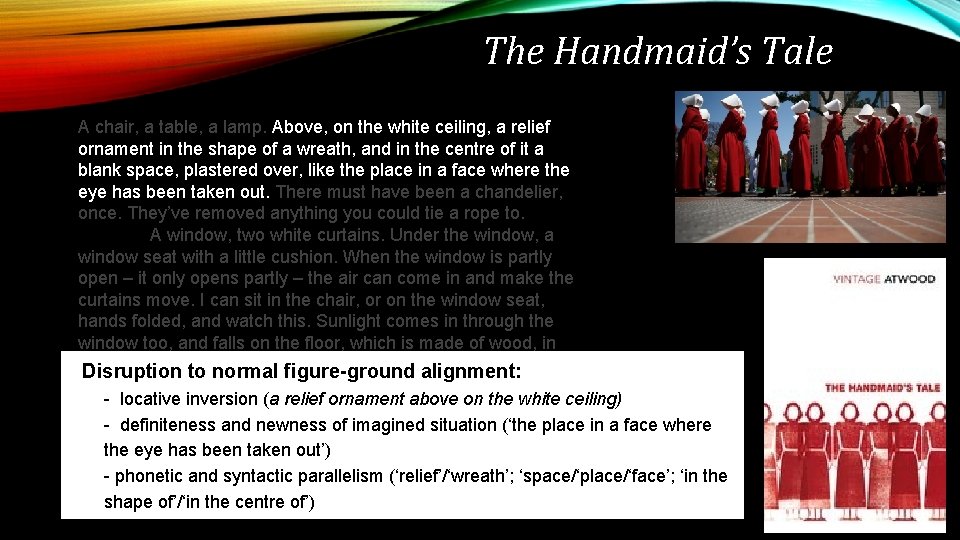

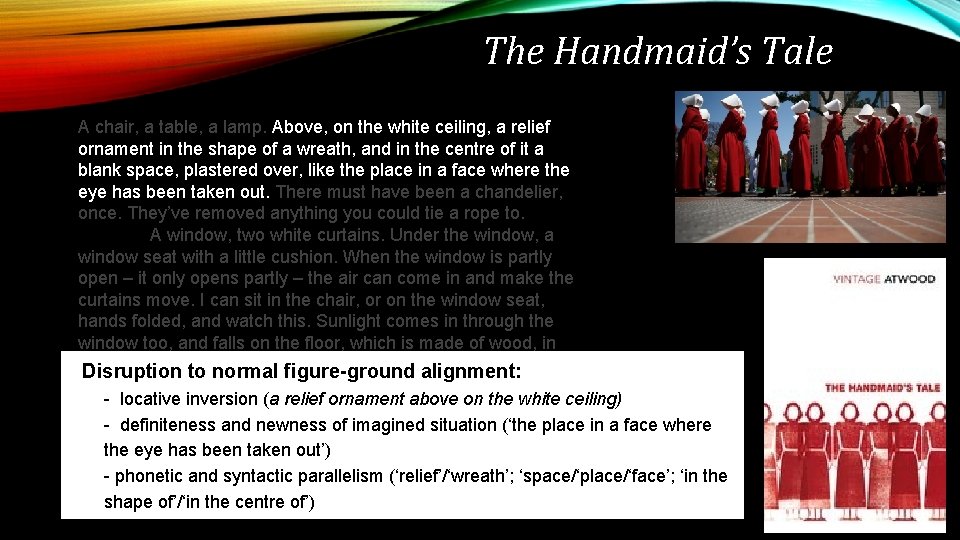

The Handmaid’s Tale A chair, a table, a lamp. Above, on the white ceiling, a relief ornament in the shape of a wreath, and in the centre of it a blank space, plastered over, like the place in a face where the eye has been taken out. There must have been a chandelier, once. They’ve removed anything you could tie a rope to. A window, two white curtains. Under the window, a window seat with a little cushion. When the window is partly open – it only opens partly – the air can come in and make the curtains move. I can sit in the chair, or on the window seat, hands folded, and watch this. Sunlight comes in through the window too, and falls on the floor, which is made of wood, in narrow strips, highly polished. I can smell the polish. There’s a rug on the floor, oval, of braided rags. This is the kind of touch they like: folk art, archaic, made by women, in their spare time, from things that have no further use. A return to traditional values. Waste not want not. I am not being wasted. Why do I want?

The Handmaid’s Tale A chair, a table, a lamp. Above, on the white ceiling, a relief ornament in the shape of a wreath, and in the centre of it a blank space, plastered over, like the place in a face where the eye has been taken out. There must have been a chandelier, once. They’ve removed anything you could tie a rope to. A window, two white curtains. Under the window, a window seat with a little cushion. When the window is partly open – it only opens partly – the air can come in and make the curtains move. I can sit in the chair, or on the window seat, hands folded, and watch this. Sunlight comes in through the window too, and falls on the floor, which is made of wood, in narrow strips, highly polished. I can smell the polish. There’s a rug on the floor, oval, of braided rags. This is the kind of touch they like: folk art, archaic, made by women, in their spare time, from things that have no further use. A return to traditional values. Waste not want not. I am not being wasted. Why do I want?

The Handmaid’s Tale A chair, a table, a lamp. Above, on the white ceiling, a relief ornament in the shape of a wreath, and in the centre of it a blank space, plastered over, like the place in a face where the eye has been taken out. There must have been a chandelier, once. They’ve removed anything you could tie a rope to. A window, two white curtains. Under the window, a window seat with a little cushion. When the window is partly open – it only opens partly – the air can come in and make the curtains move. I can sit in the chair, or on the window seat, hands folded, and watch this. Sunlight comes in through the window too, and falls on the floor, which is made of wood, in narrow strips, to highly polished. I can smell the polish. There’s a Disruption normal figure-ground alignment: rug on the floor, oval, of braided rags. This is the kind of touch - locative inversion (a relief ornament above on the white ceiling) they like: folk art, archaic, made by women, in their spare time, - things definiteness andno newness imagined (‘the place in a face where from that have further of use. A returnsituation to traditional the eye hasnot been taken values. Waste want not. out’) I am not being wasted. Why do I want? - phonetic and syntactic parallelism (‘relief’/‘wreath’; ‘space/‘place/‘face’; ‘in the shape of’/‘in the centre of’)

LANGUAGE AS (MENTAL) REPRESENTATION • The concept of foregrounding in stylistics provides practical tools and systematic methods for describing the effects of linguistic choices in texts. • Cognitive stylistics provides a further means of understanding this relationship between form and effect. ‘What is new about cognitive stylistics is the way in which linguistic analysis is systematically based on theories that relate linguistic choices to cognitive structures and processes. This provides more systematic and explicit accounts of the relationship between texts on the one hand responses and interpretations on the other. ’ (Semino and Culpeper 2002: ix)

REFERENCES Hamilton, C. (2003) ‘A cognitive grammar of “Hospital Barge” by Wilfred Owen’, in Gavins, J. and Steen, G. (eds), Cognitive Poetics in Practice (pp. 55– 67). Abingdon: Routledge. Jeffries, L. and Mc. Intyre, D. (2010) Stylistics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Leech, G. (1970) ‘“This Bread I Break”: Language and Interpretation’, in Freeman, D. (ed), Linguistics and Literary Style (pp. 119– 28). New York: Holt, Rineheart and Winston. Macrae, A. (2016) ‘Stylistics’, in Giovanelli, M. and Clayton, D. (eds), Knowing About Language: Linguistics and the Secondary English Classroom. Abingdon: Routledge. Mukařovský, J. (1964) ‘Standard language and poetic language’, in Garvin P. (ed), A Prague School Reader on Esthetics, Literary Structure and Style (pp. 17– 30). Washington: Georgetown University Press. Nuttall, L. (2014) ‘Constructing a text world for The Handmaid’s Tale’, in Harrison, C. , Nuttall, L. , Stockwell, P. and Yuan, W. (eds), Cognitive Grammar in Literature. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. Semino, E. and Culpeper, J. (2002) ‘Foreward’, in Cognitive Stylistics: Language and Cognition in Text Analysis (pp. ix–xvi). Amsterdam: John Benjamins. Stockwell, P. (2009) Texture: A cognitive Aesthetics of Reading. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. West, D. (2011) ‘Teaching cognitive stylistics’, in Jeffries, L. and Mc. Intyre, D. (eds), Teaching Stylistics (pp. 239 – 254). London: Palgrave Macmillan.

ANY QUESTIONS? www. linguisticsathuddersfield. com Twitter: @Hudd. Linguistics @Louise. Nuttall

Edexcel alevel history

Edexcel alevel history Aqa alevel data sheet

Aqa alevel data sheet Drama alevel

Drama alevel Aqa alevel psychology

Aqa alevel psychology Kim kroll

Kim kroll Left linear grammar to right linear grammar

Left linear grammar to right linear grammar Meaning:symposium

Meaning:symposium Strengths of traditional grammar

Strengths of traditional grammar Chomsky hierarchy

Chomsky hierarchy Right linear grammar

Right linear grammar Characteristics of symposium

Characteristics of symposium Nesc academy

Nesc academy Shock and vibration symposium

Shock and vibration symposium Fspos

Fspos Typiska drag för en novell

Typiska drag för en novell Nationell inriktning för artificiell intelligens

Nationell inriktning för artificiell intelligens Returpilarna

Returpilarna Shingelfrisyren

Shingelfrisyren En lathund för arbete med kontinuitetshantering

En lathund för arbete med kontinuitetshantering Personalliggare bygg undantag

Personalliggare bygg undantag Personlig tidbok fylla i

Personlig tidbok fylla i A gastrica

A gastrica Vad är densitet

Vad är densitet Datorkunskap för nybörjare

Datorkunskap för nybörjare Stig kerman

Stig kerman Att skriva en debattartikel

Att skriva en debattartikel