God and Morality The Euthyphro Dilemma Divine Command

- Slides: 21

God and Morality: The Euthyphro Dilemma

Divine Command Theory • Divine Command Theory says that what it is to be morally bad, morally permissible, or morally good is to be prohibited, permitted, or commanded by God. • Importantly, this doesn’t just mean that God’s commands reveal or give us knowledge of what is morally bad, permissible, and good. It means that things are morally bad, permissible, or good because of God’s will. • If Divine Command Theory said merely that His commands give us knowledge of right and wrong, then God would be no important than a parent.

The Euthyphro Dilemma • Socrates asks Euthyphro to give a definition of “holiness”: to say what holiness is. • One of Euthyphro’s answers is that to be holy is to be loved by all of the gods. • Socrates asks, “are things holy because they are loved by the gods, or are they loved by the gods because they are holy? ”

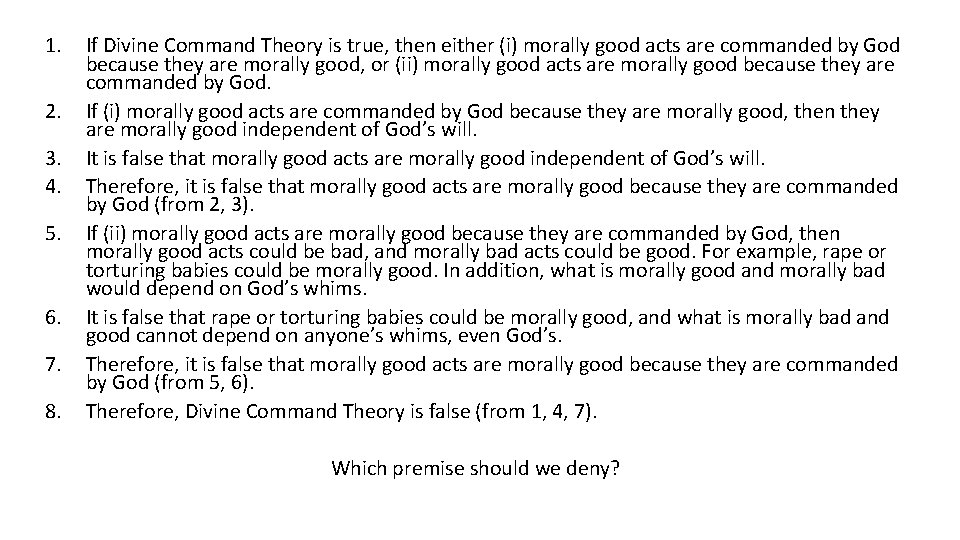

The Euthyphro Dilemma and Divine Command Theory Using Socrates’s question as an inspiration, we can ask the same question about Divine Command Theory. We can state the question as a premise of an argument. 1. If Divine Command Theory is true, then either (i) morally good acts are commanded by God because they are morally good, or (ii) morally good acts are morally good because they are commanded by God. This is called a dilemma because it presents two options for Divine Command Theory. The Divine Command Theory must select one of these options. But both options lead to consequences that are unacceptable for Divine Command Theory.

The Divine Command Theorist must reject the first option of the dilemma. 1. If Divine Command Theory is true, then either (i) morally good acts are commanded by God because they are morally good, or (ii) morally good acts are morally good because they are commanded by God. 2. If (i) morally good acts are commanded by God because they are morally good, then they are morally good independent of God’s will. 3. It is false that morally good acts are morally good independent of God’s will. 4. Therefore, it is false that morally good acts are commanded by God because they are morally good.

What about the second option? 1. If Divine Command Theory is true, then either (i) morally good acts are commanded by God because they are morally good, or (ii) morally good acts are morally good because they are commanded by God. 2. If (ii) morally good acts are morally good because they are commanded by God, then morally good acts could be bad, and morally bad acts could be good. For example, rape or torturing babies could be morally good. In addition, what is morally good and morally bad would depend on God’s whims. 3. It’s false that rape or torturing babies could be morally good, and what is morally bad and good cannot depend on anyone’s whims, even God’s. 4. Therefore, it’s false that morally good acts are morally good because they are commanded by God.

The first premise of the argument says that 1. If Divine Command Theory is true, then either (i) morally good acts are commanded by God because they are morally good, and (ii) morally good acts are morally good because they are commanded by God, then Divine Command Theory is false. We’ve argued that both (i) and (ii) are false. Therefore, Divine Command Theory is false.

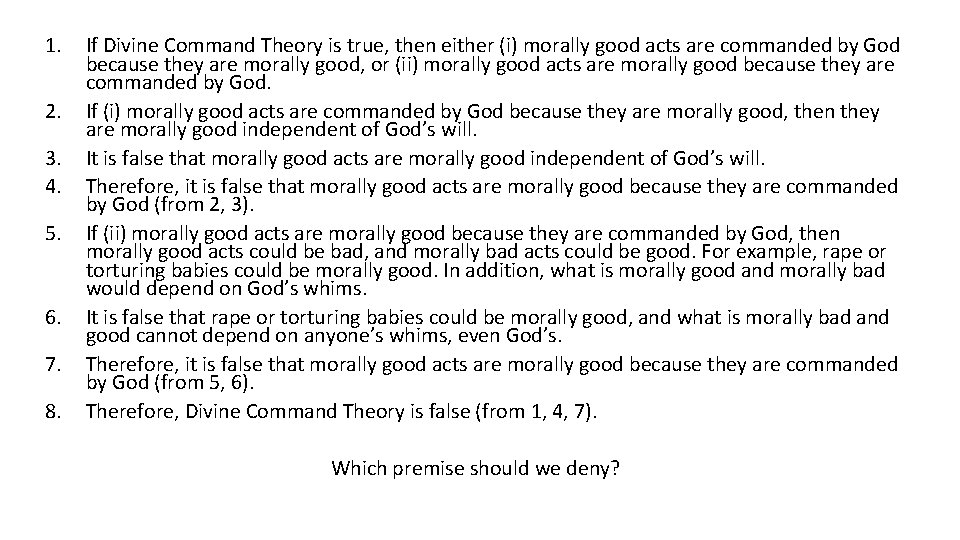

1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. If Divine Command Theory is true, then either (i) morally good acts are commanded by God because they are morally good, or (ii) morally good acts are morally good because they are commanded by God. If (i) morally good acts are commanded by God because they are morally good, then they are morally good independent of God’s will. It is false that morally good acts are morally good independent of God’s will. Therefore, it is false that morally good acts are morally good because they are commanded by God (from 2, 3). If (ii) morally good acts are morally good because they are commanded by God, then morally good acts could be bad, and morally bad acts could be good. For example, rape or torturing babies could be morally good. In addition, what is morally good and morally bad would depend on God’s whims. It is false that rape or torturing babies could be morally good, and what is morally bad and good cannot depend on anyone’s whims, even God’s. Therefore, it is false that morally good acts are morally good because they are commanded by God (from 5, 6). Therefore, Divine Command Theory is false (from 1, 4, 7). Which premise should we deny?

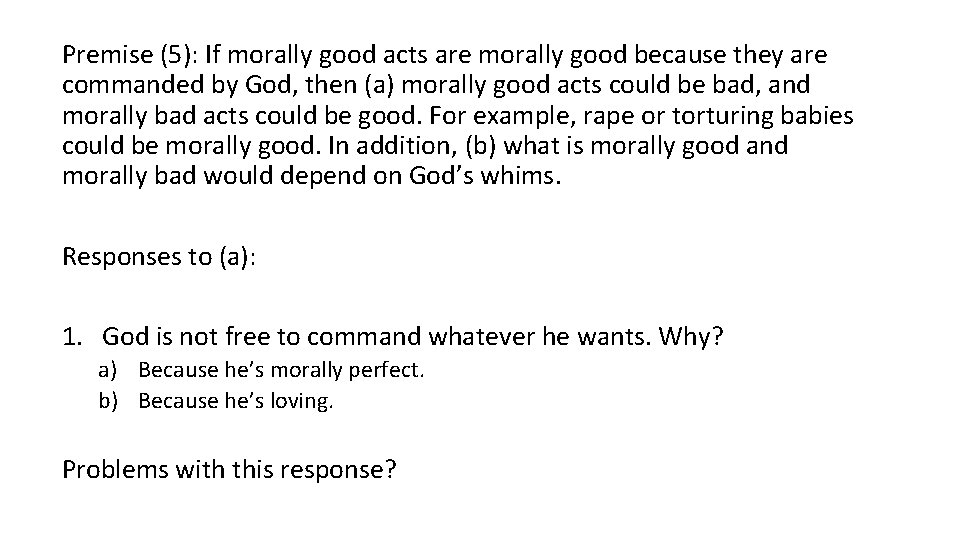

Premise (5): If morally good acts are morally good because they are commanded by God, then (a) morally good acts could be bad, and morally bad acts could be good. For example, rape or torturing babies could be morally good. In addition, (b) what is morally good and morally bad would depend on God’s whims. Responses to (a): 1. God is not free to command whatever he wants. Why? a) Because he’s morally perfect. b) Because he’s loving. Problems with this response?

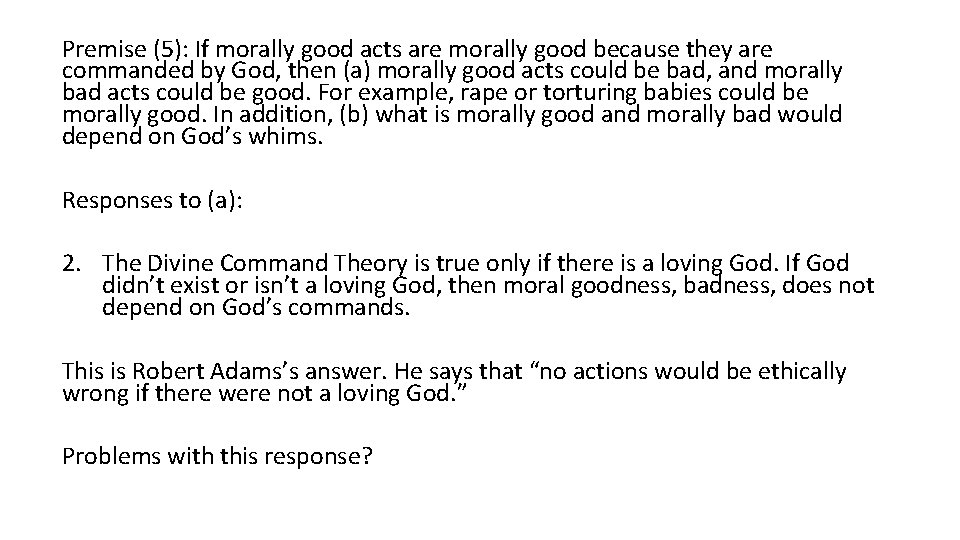

Premise (5): If morally good acts are morally good because they are commanded by God, then (a) morally good acts could be bad, and morally bad acts could be good. For example, rape or torturing babies could be morally good. In addition, (b) what is morally good and morally bad would depend on God’s whims. Responses to (a): 2. The Divine Command Theory is true only if there is a loving God. If God didn’t exist or isn’t a loving God, then moral goodness, badness, does not depend on God’s commands. This is Robert Adams’s answer. He says that “no actions would be ethically wrong if there were not a loving God. ” Problems with this response?

Premise (5): If morally good acts are morally good because they are commanded by God, then (a) morally good acts could be bad, and morally bad acts could be good. For example, rape or torturing babies could be morally good. In addition, (b) what is morally good and morally bad would depend on God’s whims. Responses to (b): ? ? ?

God and Morality: Erik Wielenberg’s Theory

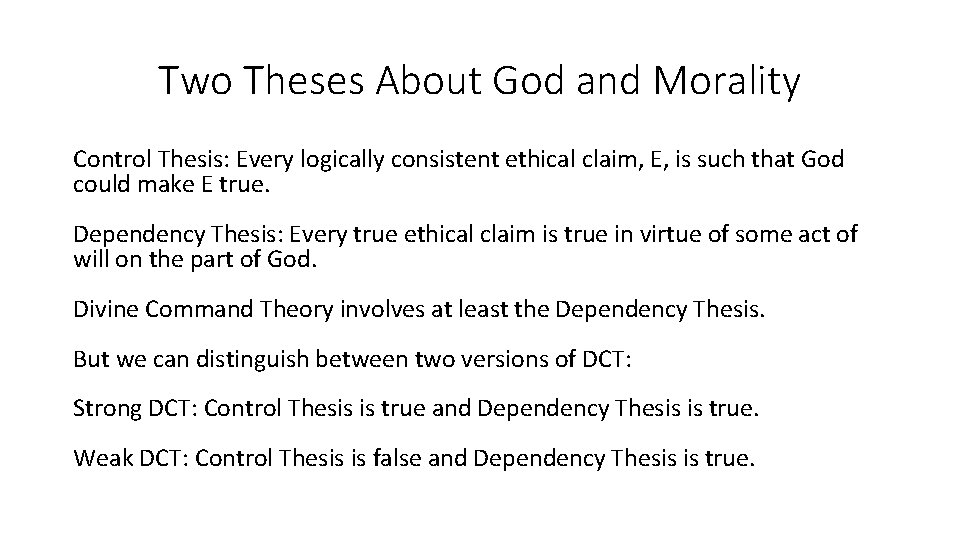

Two Theses About God and Morality Control Thesis: Every logically consistent ethical claim, E, is such that God could make E true. Dependency Thesis: Every true ethical claim is true in virtue of some act of will on the part of God. Divine Command Theory involves at least the Dependency Thesis. But we can distinguish between two versions of DCT: Strong DCT: Control Thesis is true and Dependency Thesis is true. Weak DCT: Control Thesis is false and Dependency Thesis is true.

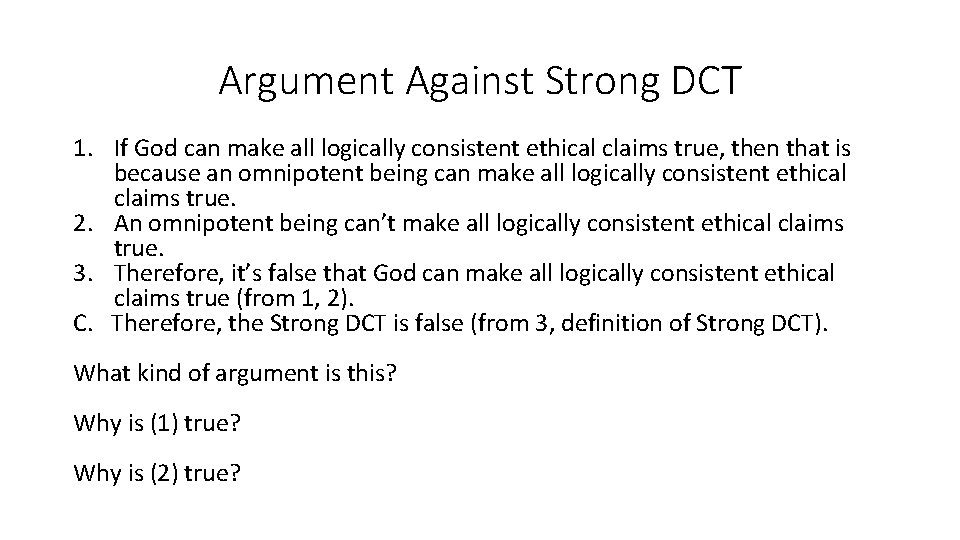

Argument Against Strong DCT 1. If God can make all logically consistent ethical claims true, then that is because an omnipotent being can make all logically consistent ethical claims true. 2. An omnipotent being can’t make all logically consistent ethical claims true. 3. Therefore, it’s false that God can make all logically consistent ethical claims true (from 1, 2). C. Therefore, the Strong DCT is false (from 3, definition of Strong DCT). What kind of argument is this? Why is (1) true? Why is (2) true?

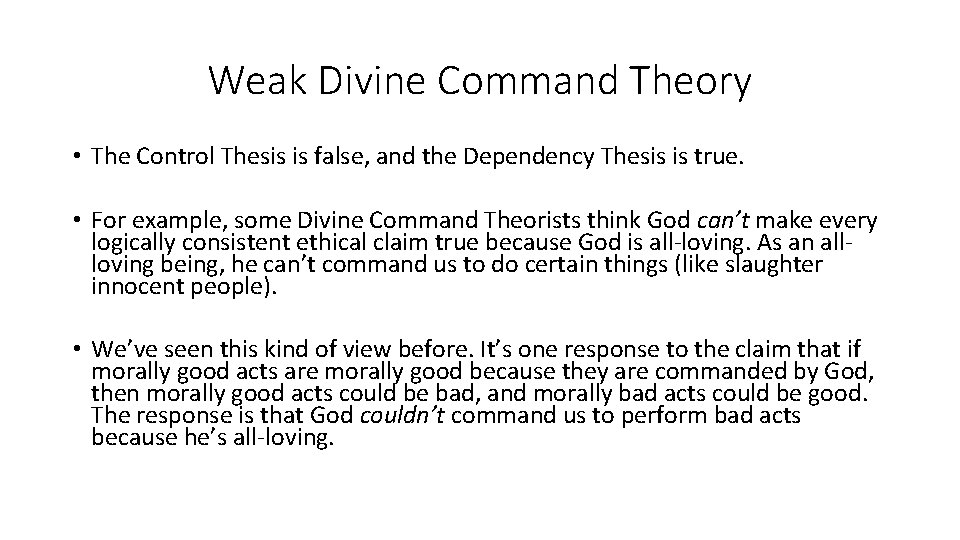

Weak Divine Command Theory • The Control Thesis is false, and the Dependency Thesis is true. • For example, some Divine Command Theorists think God can’t make every logically consistent ethical claim true because God is all-loving. As an allloving being, he can’t command us to do certain things (like slaughter innocent people). • We’ve seen this kind of view before. It’s one response to the claim that if morally good acts are morally good because they are commanded by God, then morally good acts could be bad, and morally bad acts could be good. The response is that God couldn’t command us to perform bad acts because he’s all-loving.

Argument Against Weak DCT 1. If every true ethical claim is true in virtue of some act of will on the part of God, then nothing is intrinsically good or bad except God’s will. 2. Pain is intrinsically bad and is distinct from God’s will. 3. Therefore, it’s false that every true ethical claim is true in virtue of some act of will on the part of God (from 1, 2). C. Therefore, the Weak DCT is false (from 3, definition of Weak DCT). What kind of argument is this? Why is (1) true? Why is (2) true?

Omnipotence and Necessary Truths Part of the argument against Strong DCT was the claim that: An omnipotent being can’t make all logically consistent ethical claims true. Weilenberg initially supports this with a thought experiment, but he has a deeper reason for thinking this. He thinks some ethical truths are necessary truths, and even omnipotent beings cannot make necessary truths false. 2+2=4 is a necessary truth. God cannot make 2+2=5. For the same reason, he cannot make some ethical claims false. For example, he can’t make it false that pain is intrinsically bad. Hence, it turns out that even if God can’t make all logically consistent ethical claims true, he can still be omnipotent.

God as Morally Authorized Commander • Wielenberg has argued that God is not the source of all true ethical claims, and that he cannot make any logically consistent ethical claim true. • But there is another way in which God’s commands could have moral significance. Perhaps God’s commands give us all our moral obligations; without God, everything would be permitted. This is “Karamazov’s Thesis. ” • Why would this be true? There are number of proposals. 1. We are God’s property, and he has the moral right to tell us what to do. 2. We are God’s creations, and we are morally obligated by gratitude to do what he wants us to do. 3. God is morally perfect, so his commands are just.

Why This Isn’t Divine Command Theory • The idea that God’s commands are the source of all our moral obligations (Karamazov’s Thesis) is quite different from the idea that God’s commands are the source of all ethical truths (Dependency Thesis). • First of all, if Karamazov’s Thesis is true and if God didn’t exist, there would still be some ethical truths—“murder is permissible, ” for example, would be true. • Second, the reasons why God might be the source of all our moral obligations all point to some prior moral feature of God or his relationship to us as the source of our obligations—for example, that he has a right to his property. This moral feature is independent of God’s will.

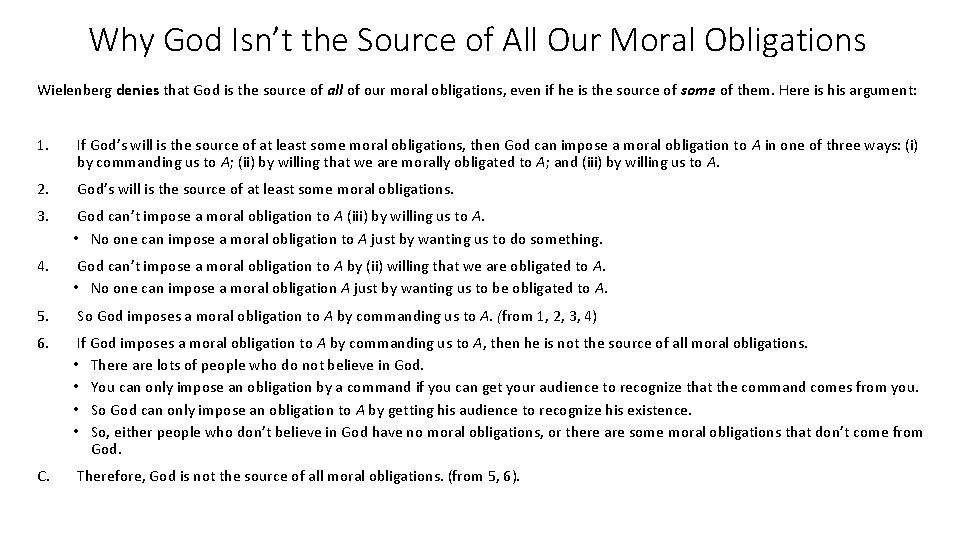

Why God Isn’t the Source of All Our Moral Obligations Wielenberg denies that God is the source of all of our moral obligations, even if he is the source of some of them. Here is his argument: 1. If God’s will is the source of at least some moral obligations, then God can impose a moral obligation to A in one of three ways: (i) by commanding us to A; (ii) by willing that we are morally obligated to A; and (iii) by willing us to A. 2. God’s will is the source of at least some moral obligations. 3. God can’t impose a moral obligation to A (iii) by willing us to A. • No one can impose a moral obligation to A just by wanting us to do something. 4. God can’t impose a moral obligation to A by (ii) willing that we are obligated to A. • No one can impose a moral obligation A just by wanting us to be obligated to A. 5. So God imposes a moral obligation to A by commanding us to A. (from 1, 2, 3, 4) 6. If God imposes a moral obligation to A by commanding us to A, then he is not the source of all moral obligations. • There are lots of people who do not believe in God. • You can only impose an obligation by a command if you can get your audience to recognize that the command comes from you. • So God can only impose an obligation to A by getting his audience to recognize his existence. • So, either people who don’t believe in God have no moral obligations, or there are some moral obligations that don’t come from God. C. Therefore, God is not the source of all moral obligations. (from 5, 6).

Questions • Do you agree with the argument against Strong DCT? • Do you agree with the argument against Weak DCT? • Do you agree with the argument against Karamazov’s Thesis?