GHEI Module 4 C Fundamentals of Public Health

GHEI Module 4 C: Fundamentals of Public Health Practice Charles Gardner, MD, CCFP, MHSc, FRCPC Medical Officer of Health, Simcoe Muskoka District Health Unit September 3, 2013

Acknowledgement Dr. Liane Macdonald, BA MD MSc(PH) FRCPC Dr. Natalie Bocking, MD MIPH CCFP

Objectives: 1. Understand health promotion approaches to public health practice 2. Understand the difference between primary, secondary and tertiary prevention strategies 3. Become familiar with the current challenges and opportunities for global tobacco control efforts, drawing upon the history of tobacco control in Canada and Ontario, with reflections on transferable lessons regarding other health hazards.

Health Promotion Health: “A state of complete physical, social and mental well-being, and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity. ” (WHO 1948) Health for all: “The attainment by all the people of the world of a level of health that will permit them to lead a socially and economically productive life. ” (WHO 1984) Health promotion: “The process of enabling people to increase control over their health and its determinants, and thereby improve their health. ” (Ottawa Charter 1986) World Health Organization(WHO). Health Promotion Glossary. Geneva: 1998. WHO/HPR/HEP/98. 1.

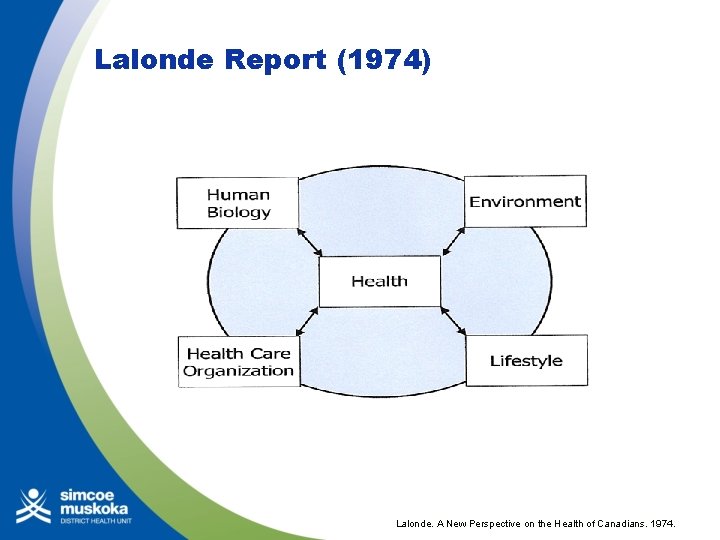

Lalonde Report (1974) Lalonde. A New Perspective on the Health of Canadians. 1974.

Ottawa Charter for Health Promotion (1986) Ottawa Charter for Health Promotion. WHO, Geneva: 1986. WHO/HPR/HEP/95. 1/

Bangkok Charter (2005) Critical issues: Globalization as a source of challenges and opportunities; Need for policy coherence Key Commitments to make the promotion of health: § central to the global development agenda § a core responsibility for all of government § a key focus of communities and civil society § a requirement for good corporate practice. Bangkok Charter for Health Promotion in a Globalized World. 6 th. Global Conference on Health Promotion. Bangkok: 2005.

Theory in Health Promotion Using theory can guide the selection of the best health promotion interventions for a given problem HP theories and models explain health behaviour and change at the level of: • Individuals • Communities • Communication strategies • Organizations • Healthy public policy processes Poole J. So what about health promotion? The history, the ideas, the projects. July 2006.

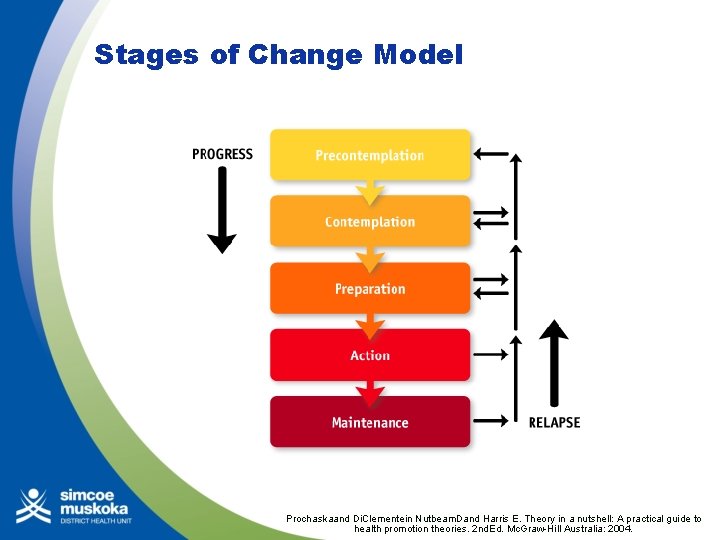

Stages of Change Model Prochaskaand Di. Clementein Nutbeam. Dand Harris E. Theory in a nutshell: A practical guide to health promotion theories. 2 nd. Ed. Mc. Graw-Hill Australia: 2004.

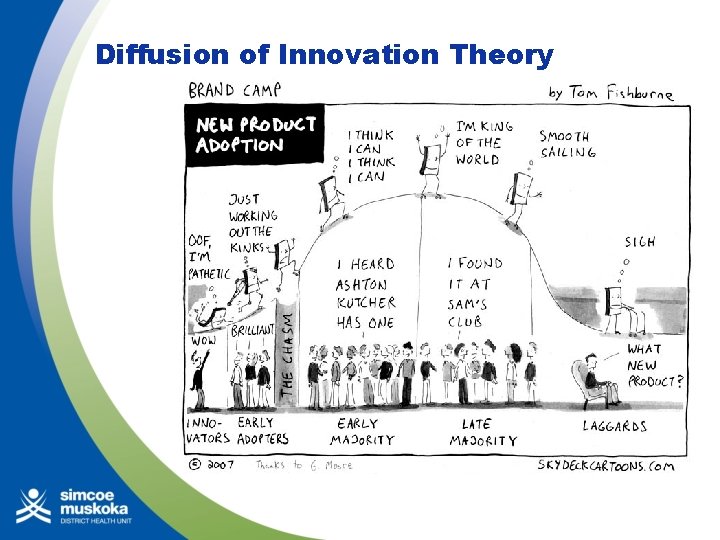

Diffusion of Innovation Theory

The Social Marketing Approach l l l Uses commercial marketing techniques to benefit individuals / society Consumer-driven, with defined subgroups 4 P’s of an effective “marketing mix”: l Product: behaviour/social change + its benefits l Price: barriers / costs (e. g. $, time) l Place: making behaviour change easy and convenient l Promotion: delivering the message to the target audience National Cancer Institute. Theory at a Glance: A Guide for Health Promotion Practice, 2 nd. Ed. US Department of Health and Human Services. 2005: 36 -7.

The Advocacy Approach Advocacy: “A combination of individual and social actions designed to gain political commitment, policy support, social acceptance and systems support for a particular health goal or programme. ” Public health media advocacy: “The strategic use of news media to advance a public policy initiative. ” World Health Organization(WHO). Health Promotion Glossary. Geneva: 1998. WHO/HPR/HEP/98. 1. Chapman S. Advocacy for public health : a primer. J Epidemiol. Community Health 2004; 58: 361 -5.

Primary Prevention of Disease Goal: To protect healthy people from developing a disease or experiencing an injury in the first place. Examples: l Health education and behavioural change • Immunization • Social benefits guidance • Community development Gillam. S. The practice of public health in primary care. In Pencheonet al. Oxford Handbook of Public Health. Oxford UP: 2006. 286.

Secondary Prevention Goal: To halt or slow the progress of disease (if possible) in its earliest stages; in the case of injury, goals include limiting long-term disability and preventing re-injury. Examples: • Reduce risk of future ill-health (e. g. screen for HTN, treat with meds, reduce CVD and CVA risk) • Give information (e. g. screen pregnant woman for trisomy 21) Gillam. S. The practice of public health in primary care. In Pencheonet al. Oxford Handbook of Public Health. Oxford UP: 2006. 286.

Tertiary Prevention Goal: To prevent further physical deterioration and maximize quality of life. Examples: • cardiac or stroke rehabilitation programs • chronic pain management programs • patient support groups Gillam. S. The practice of public health in primary care. In Pencheonet al. Oxford Handbook of Public Health. Oxford UP: 2006. 286.

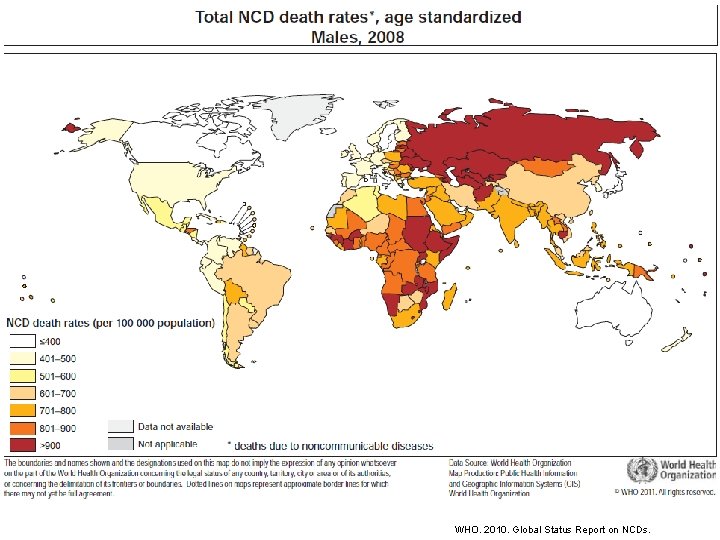

Non-communicable Diseases (NCD) Leading cause of death globally 80% of NCD deaths occur in low-middle income countries: 1. Cardiovascular disease 2. Cancer 3. Diabetes 4. Chronic lung disease WHO. 2010. Global Status Report on NCDs.

WHO. 2010. Global Status Report on NCDs.

NCDs Caused by 4 behavioural risk factors: • Tobacco use • Unhealthy diet • Insufficient physical activity • Harmful use of alcohol WHO. 2010. Global Status Report on NCDs.

TOBACCO Lessons from the Battles of a Half Century

Acknowledgements Insights and background materials from discussions with the following: § Robert Kyle, MOH Durham Region, former TSAG member § David Butler-Jones, Chief Public Health Officer of Canada § John Garcia, Assoc. Prof. and Dir. , School of Public Health, U of Waterloo; former Dir. of the Health Promotion Branch, ON. Min of Health § Kate Manson-Smith, ADM of Health Promotion Division, MOHLTC § Michael Perley, E. D. , OCAT § Richard Schabas, MOH, HPEHU; former CMOH ON.

One-Billion Deaths… …may occur globally in the 21 st century from tobacco use (WHO, 2008) § 100 million deaths in the 20 th century § “Cigarettes are the only legal product that, when used as intended, are lethal” § Despite this, things have really changed in Canada since 1964 (or even 1984) • Majority of adult males (including physicians) were smokers • Smoking at board of health meetings … and at Ministry / MOH meetings • Smoking in all indoor public places • No real restrictions on tobacco marketing activities

The Breadth of Health Impacts of Tobacco: Surgeon General’s Report 2010

Health Impacts of Tobacco THE leading preventable cause of death in the world. • Causes 1 in 10 adult deaths worldwide • Kills up to 50% of all users • Nearly 80% of the world's one billion smokers live in low- and middle-income countries. http: //www. who. int/features/factfiles/tobacco/en/index. html

Health Impacts of Tobacco use is responsible for: • 10% of all deaths from cardiovascular disease • 22% of all cancer deaths • 71% of all lung cancer deaths • 36% of all deaths from the respiratory system • 42% of all COPD deaths WHO. 2012. WHO Global Report: Mortality Attributable to Tobacco.

The rise and fall of tobacco use and disease

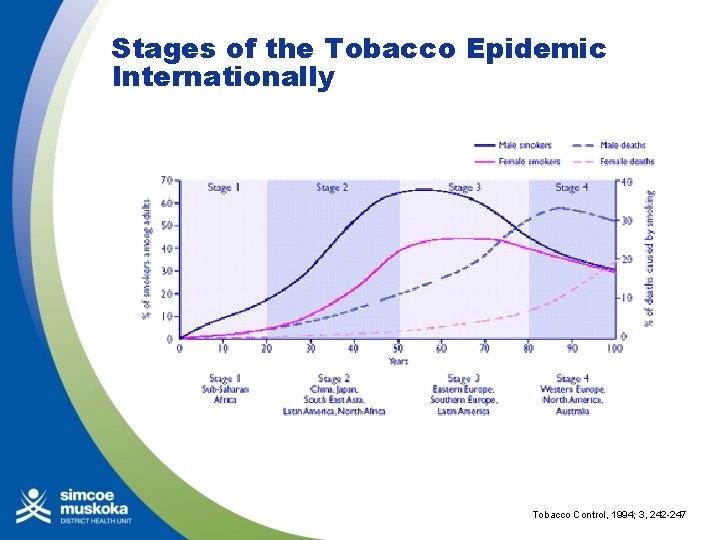

Stages of the Tobacco Epidemic Internationally Tobacco Control, 1994; 3, 242 -247

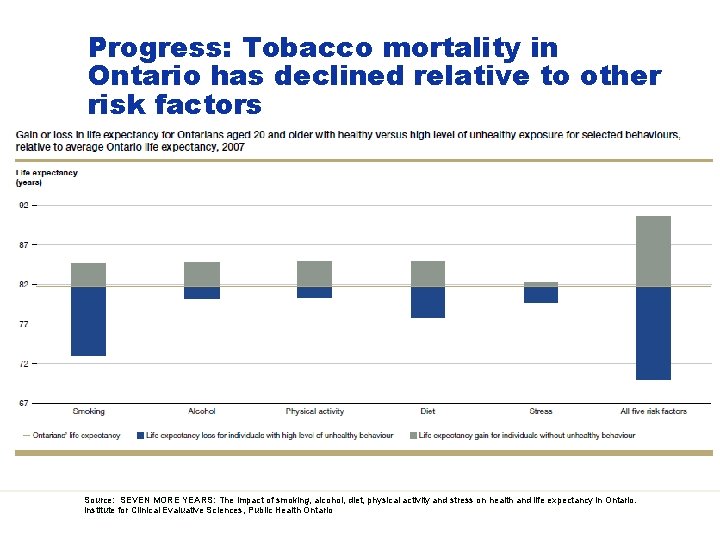

Progress: Tobacco mortality in Ontario has declined relative to other risk factors Source: SEVEN MORE YEARS: The impact of smoking, alcohol, diet, physical activity and stress on health and life expectancy in Ontario. Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences, Public Health Ontario

Taking stock of the present status of tobacco control in Ontario § Research, surveillance and KE § Strategies – Prevention, Protection, Cessation § National, provincial and municipal legislation § Litigation § Local public health programs (Ministry funded) § NGO advocacy / public education § Healthcare system supports for cessation § Public support for the above § But … ongoing dedicated opposition from the industry… and thus despite 60 years of evidence supporting action, 1/5 adults still smoke; 13, 000 deaths annually in Ontario

Some key questions re tobacco and its history 1. How did we get here? • Understanding the basic dynamics of an industry-driven epidemic 2. Where do we go from here? • Understanding the political challenges of implementing effective practices 3. What lessons can be applied to other leading preventable cause(s) of death? • Identifying transferable lessons regarding other prominent causes of chronic disease

Phases of the Tobacco Epidemic PHASE I: 1884 -1914 Consolidation of the Cigarette Industry and Early Controversies PHASE II: 1914 -1950 Era of Good Feeling; Cigarettes Promoted by Governments PHASE III: 1950 -1964 The Gathering Storm of Health Concerns PHASE IV: 1964 -1984 Regulatory Hesitancy PHASE V: 1984 -2008 Tobacco as Social Menace PHASE VI: The Future Neoprohibitionism versus harm reduction? Source: Local Tobacco Control Coalitions in the United States and Canada: Contagion Across the Border? Stephanie J. Frisbee, Ph. D, and Donley T. Studlar, Ph. D. Presented at: 11 th Annual Conference of the Canadian Political Science Association May 16‐ 18, 2011, Wilfrid Laurier University, Waterloo, ON

Research: Early Concerns Early health (and moral) concerns: § “loathsome to the eye, hatefull to the nose, and harmefulle to the braine”, King James I, 17 th century Scientific reports as early as 1912 re lung cancer Concerns in the 1920 s to 1940 s § Reader’s Digest in 1924; Science in 1938 (Johns Hopkins biostats study – reduced longevity); small study in Germany in 1939 re increased lung cancer with smoking; Departments of Pensions and National Health in 1940

Research: The Evidence Gathers § 1947 – Norman Delarus (Canadian), case (50) control study re lung cancer. § 1950 – Evart Graham (USA), JAMA, case (605) control study re lung cancer (author quit smoking after study, but died of lung cancer in 1957). § 1950 – Bradford Hill, Richard Doll, BMJ, 20 British hospitals, case control study, lung cancer. § 1951 – Richard Doll et al. Commencement of a 50 -year-long cohort study on male physicians in the UK

Surgeon General Reports on Tobacco 29 reports in all – latest one in 2012 Ø 1964 landmark first report § Based on 7, 000 articles relating to smoking and disease § Very guarded language § Citation of antecedent work § Dramatic increase in tobacco use and lung cancer (from 3 T in 1930 to 41 T in 1962) over past century § No relationship with education – urban more than rural § Cancer of lungs, etc. , probably COPD, heart disease, LBW babies, fires § “Habituation”, not addiction

Surgeon General Reports: Progression 1979 § Much more strident language § “The largest preventable cause of death” § An addiction § Reductions in use 1986 § “Involuntary smoking” hazards § ETS restrictions in 40 states and in DC § “ 96 percent of businesses have adopted smoking policies” § Restrictions may reduce tobacco use – evaluation needed

Research / Analysis • Ontario Council on Health Report, Smoking and Health in Ontario: A Need for Balance, 1982 • USEPA, 1992 • Australian National Health and Medical Research Council in 1997 • California EPA, 1997 • United Kingdom Scientific Committee on Tobacco and Health, 1998 • WHO, 1999 • Actions will Speak Louder than Words, 1999 • US National Toxicology Program, 2000 • Protection from secondhand tobacco smoke in Ontario, OTRU, 2001 • Evidence to Guide Action, PHO, 2010 • The Tobacco Strategy Advisory Committee (TSAG) report and recommendations, 2010

The Industry’s Response Some historic milestones • Macdonald Tobacco established in Montreal in 1858 • Cigarette rolling machine in 1881; safe matches in 1890 s “Ability of T. industry to remain healthy while its customers get sick “one of the most amazing marketing feats of all times” – Jake Epp, 1996 Tremendous wealth • £ 19. 7 billion in duty paid in 2010 in the Americas (BAT – “Managing the Challenges in the Americas”) Present companies in Canada • Imperial Tobacco • Rothmans, Benson & Hedges Inc. • JTI-Mac. Donald Corp James Albert Bonsack's cigarette rolling machine, invented in 1880 and patented in 1881. (Wikipedia)

The Industry’s Response • Deliberate deception • Public declaration of responsibility as a ruse • Sponsorship of scientific opposition • Denial of the health impacts • Personal responsibility arguments • Marketing to youth (and denying it) • Marketing to recruit new smokers (and denying it) • Policy manipulation • Political involvement – prominent politicians as tobacco executives • Voluntary code re marketing as a means of forestalling legislation (effective in the 1970’s) • Threatened withdrawal of sponsorship as means of coercion • Contraband tobacco • Undermining price as a control measure • Legal challenges • Supreme Court re the Tobacco Products Control Act

Knowledge Exchange and Grass-roots Advocacy in Canada / Ontario § Canadian Cancer Society – newsletter in 1951 citing the emerging evidence § Canadian Public Health Association – Advocacy positions in 1959, 1988, and 2011 – Seeking elimination (under 1%) by 2035 § Canadian Medical Association – concluded in 1961 smoking causes lung cancer § Non‐Smokers’ Rights Association, and the Canadian Council on Smoking and Health, (now the Canadian Council for Tobacco Control) founded in 1974 § Physicians for a Smoke-Free Canada formed in 1985 § Ontario Campaign for Action on Tobacco (OCAT), 1992 § Ontario Tobacco Research Unit, 1993 § Ontario Medical Association: advocacy paper for smoke-free legislation (2003), cars and children (2004)

History of TC and Public Health in Ontario § No tobacco control in the Mandatory Health Programs and Services Guidelines until 1989 – 25 years after the Surgeon General’s report § The first CMOH Report, 1991, was on tobacco control § Mandatory Health Programs and Services Guidelines • Guidelines in 1989, and 1998 – Structure: Outcome objectives re smoking rate reductions, smoke-free homes, tobacco vendor compliance (re Tobacco Control Act) – Actions: consistent with today’s local tobacco control mandate Liaison, school curriculum, smoke-free policies in workplaces, cessation, regulatory efforts re secondhand smoke • Ontario Public Health Standards 2008 – “Chronic Disease Prevention” • Structure: broad process outcomes, Societal and Board Objectives – details in protocols

Historic Government Roles Tobacco promotion • Agricultural R&D, subsidies • Provision (military) Tobacco control • Regulation of manufacturing (such as the 2005 cigarette ignition propensity regulations) • Sales (age, vendors / vending) restrictions • Marketing / advertising / packaging (plain) / warnings (graphic) • Taxation • Research • Cessation supports • Location of use restrictions • Litigation • Partnerships • Public awareness and de-normalization • (Prohibition)

Government Response: Federal Ø For 80 years (between 1908 to 1988) the Federal Government did not pass tobacco control legislation – despite more than 20 private members’ bills in the 1960 s Ø Resolution to ban tobacco, 1903 and 1904 – second reading only Ø Legislation: • 1908 Tobacco Restraint Act - prohibited sales under 16 • 1988 Non-Smokers’ Health Act (private members bill) and Tobacco Products Control Act - prohibited advertising; charter challenge with sections ruled unconstitutional • 1993 Tobacco Sales to Young Persons Act – prohibited sales under 18 • 1997 Tobacco Act – still in effect; disclose product content, prohibited sale to youth, prohibited mail-order and vending machines, warning labels, restricted advertising Ø Taxation increases in 1980’s, reduction in 1994 • 40, 000 additional deaths Ø Graphic packaging in 2000 and 2012 Ø Tobacco farms quota buyout in 2008 • More than doubled Ontario’s crop

Government Response: Provincial (Ontario and others) § For 98 years (1892 to 1990) the provincial government of Ontario did not pass tobacco control legislation § Legislation: • Prohibition of sale to minors – BC in 1891, ON (age 18) and NS in 1892, NB in 1893, NWT in 1896 • 1990 Smoking in the Workplace Act - minimum areas for nonsmoking (not enclosed and separately ventilated) • 1994 Tobacco Control Act - Ontario’s first general tobacco control statute – prohibition of sale in pharmacies and vending machines, to minors, allowed municipal bylaws for smoke-free spaces – prohibited in healthcare facilities, pharmacies, schools and colleges and in other retail and institutional settings • Tobacco program funding: – $4 M in 1995, $10 M in 1999, to $60 M by 2006, to $47. 8 M by 2011 • Provincial government suits – BC in 2004, Supreme Court support – Manitoba, Sask. Que. , PEI, NS, NB have launched suits – Enabling legislation in Ontario and Alberta

Smoke-Free Ontario Act and Strategy, 2006 § § Comprehensive, multi-level and intensive strategy: training, mass media, planning infrastructure (such as TCANs), local programs, research and evaluation • programming and 40% of SFO funding for local public health (previously only cost-shared funding) Banning smoking in enclosed public places and workplaces § Banning the display of tobacco products at the point of purchase (i. e. powerwalls) § Strengthening restrictions on selling tobacco products to young people § Expanded services and infrastructure to help smokers quit § Created and funded programs, including a peer-to-peer infrastructure, to prevent youth from starting to smoke § Funded extensive awareness and social marketing initiatives § Funded research capacity and training supports for health system workers

Ontario since 2009 § Banned smoking in vehicles when children under 16 are present § Passed legislation to allow the government to to sue tobacco companies to recover past and ongoing healthcare costs due to tobacco-related illness § Passed legislation to address the supply of flavoured cigarillos to young people § MOHLTC Action Plan, 2012 – to have the lowest tobacco use in the country § According to 2006 Health Canada figures, legal sales of cigarettes in Ontario fell by 31. 8 percent, or by approximately 4. 6 billion cigarettes, since 2003

Local Public Health and NGO Advocacy in the 1990 s / 2000 s – Toronto: • Bylaw in 1979 prohibiting smoking in retail stores, elevators, escalators, service lineups • Bylaw in 1993 requiring workplace smoking policies • Bylaw in 1997 – enclosed, separately ventilated DSAs – rescinded – Smoke-free bylaws in 2000 / 2002: Waterloo Region, Toronto, Ottawa – Other municipalities – such as Simcoe County, District of Muskoka; Cornwall a noted success in eastern Ontario – Most of the provincial population covered by smokefree bylaws in early 2000 s - Set the stage for the SFOA – Much leadership, partnership and support from NGOs – OCAT in particular working closely with local public health

The Impact of Government Decisions Past-Year Smoking, by grades 7 -12, Ontario, 1977 -2011 Source: 2012 Smoke-Free Ontario Strategy Evaluation Report, Ontario Tobacco Research Unit: http: //otru. org/2012 -smoke-free-ontario-strategyevaluation-report-full-report/

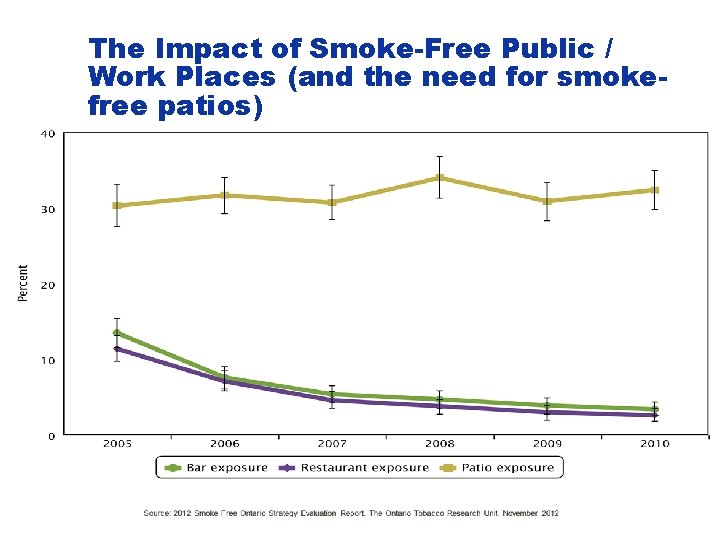

OTRU Report 2012 § Progress, however change too slow to achieve government’s & TSAG’s goals § Protects most Ontarians most of the time from ETS in indoor public places § Changing social climate and reducing use among youth • YSS report 1/3 youth remain susceptible § However, no reduction in adult smoking in 5 years – took 10 years to reduce by 5% § Protection: • Reduction in ETS exposure over 5 years • 26% still exposed at work, and 32% still on restaurant patios • 11% of aged 12 to 19 still exposed in homes – (not tracked in multiunit dwellings & likely much higher)

OTRU Report 2012 Prevention: • Reduction in youth smoking (1/2 reduction over 6 years) • Still 25% aged 20 to 24 smoke • Need to focus on high-risk schools / youth who also have a high prevalence of other risk behaviors Cessation: • In recent years no change in the proportion of smokers intending to quit, or in the number of cigarettes smoked daily • Train health professionals in providing cessation support through TEACH, RNAO and PTCC • Intention to quit not increasing • Provincial cessation supports only reaching 5% of smokers • Need to double annual quit rate from 1. 3% in order to achieve TSAG target of 5% reduction over 5 years • Need the multiple strategies in TSAG to achieve the provincial goal of the lowest smoking in Canada Source: OTRU review, http: //otru. org/2012 -smoke-free-ontario-strategy-evaluation-report-full-report/

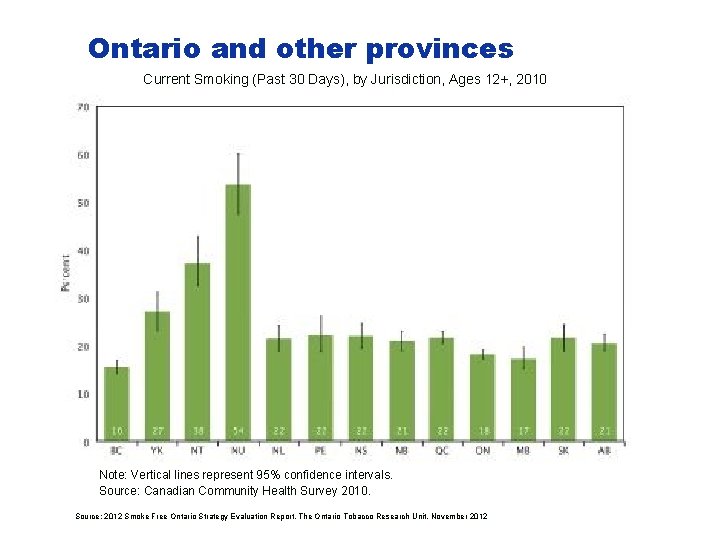

Ontario and other provinces Current Smoking (Past 30 Days), by Jurisdiction, Ages 12+, 2010 Note: Vertical lines represent 95% confidence intervals. Source: Canadian Community Health Survey 2010. Source: 2012 Smoke Free Ontario Strategy Evaluation Report. The Ontario Tobacco Research Unit. November 2012

Priority Populations Current Smoking (Past 30 Days), by Education, Ages 18+, Ontario, 2001 to 2011 Source: 2012 Smoke Free Ontario Strategy Evaluation Report. The Ontario Tobacco Research Unit. November 2012

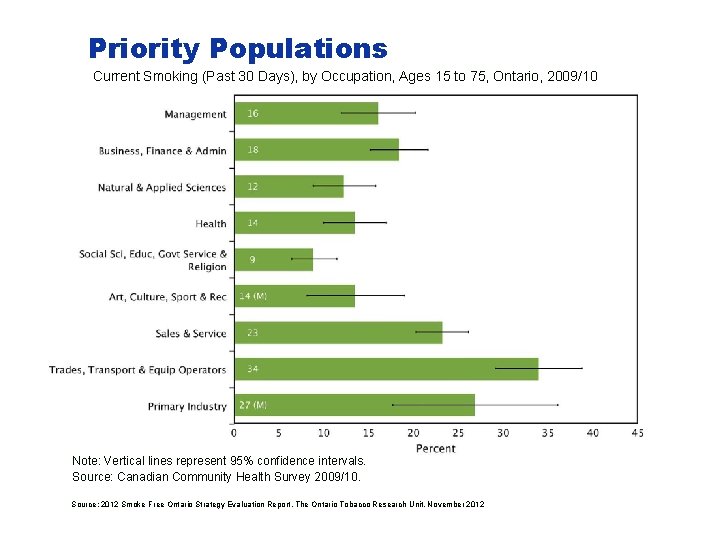

Priority Populations Current Smoking (Past 30 Days), by Occupation, Ages 15 to 75, Ontario, 2009/10 Note: Vertical lines represent 95% confidence intervals. Source: Canadian Community Health Survey 2009/10. Source: 2012 Smoke Free Ontario Strategy Evaluation Report. The Ontario Tobacco Research Unit. November 2012

The Impact of Smoke-Free Public / Work Places (and the need for smokefree patios) Christine, please include Figure 12: Exposure to SHS at Restaurants or Bars, Ages 15+, Ontario, 2005 to 2010 from 2012 Smoke Free Ontario Strategy Evaluation Report. The Ontario Tobacco Research Unit. November 2012

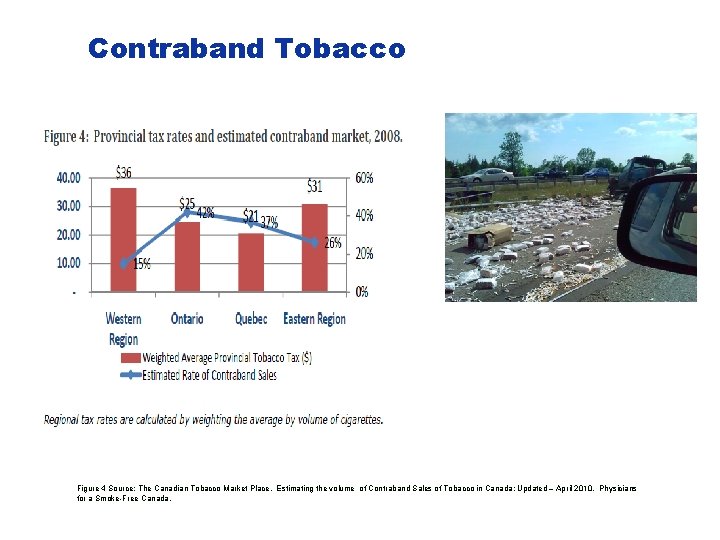

Contraband Tobacco Figure 4 Source: The Canadian Tobacco Market Place. Estimating the volume of Contraband Sales of Tobacco in Canada; Updated – April 2010. Physicians for a Smoke-Free Canada.

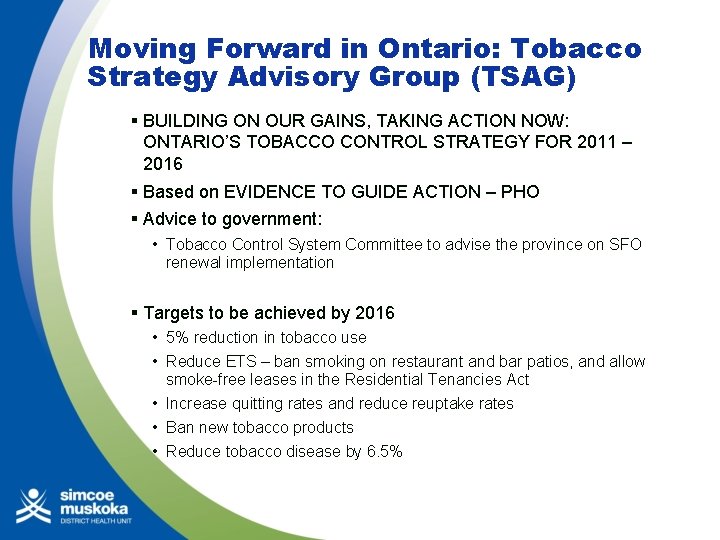

Moving Forward in Ontario: Tobacco Strategy Advisory Group (TSAG) § BUILDING ON OUR GAINS, TAKING ACTION NOW: ONTARIO’S TOBACCO CONTROL STRATEGY FOR 2011 – 2016 § Based on EVIDENCE TO GUIDE ACTION – PHO § Advice to government: • Tobacco Control System Committee to advise the province on SFO renewal implementation § Targets to be achieved by 2016 • 5% reduction in tobacco use • Reduce ETS – ban smoking on restaurant and bar patios, and allow smoke-free leases in the Residential Tenancies Act • Increase quitting rates and reduce reuptake rates • Ban new tobacco products • Reduce tobacco disease by 6. 5%

TSAG Implementation Numerous Recommendations • Whole of government approach • Supply strategies • Price, promotion, new product prohibition, reduced production, divestment • Demand strategies • Prevention, cessation, protection (MUDs), social marketing • Research, address disparities, prevent government interference, dedicated adequate funding, litigation Strategies commenced: 16 Strategies awaiting commencement / uncertain status: 32 (though 3 are being addressed by local public health, municipal government or the federal government)

TSAG Implementation Highlights of Strategies Commenced: § Whole of government approach (e. g. Min of Finance re contraband) • engagement of first nations re contraband § Tobacco growing: • Raw leaf regulation commencing in January, 2014 § Cessation: • Coordinated tobacco cessation services – hospital-based and workplace-based smoking cessation demonstration grants – increased access to counseling and pharmacotherapy through primary care • ODB coverage for cessation products

TSAG Implementation Strategies commenced: § Research • Provincial and local research, surveillance and monitoring – re initiatives, programs, policies, disparities, youth and young adult prevention § Reduce disparities • Engage First Nations (Min of Finance) § Social marketing • Social smoking provincial commercial (movies and internet – Cannes award for creativity)

TSAG Implementation Strategies awaiting commencement / uncertain status: § Sufficient resources (at least $100 M would be within the CDC recommendations) – Current strategy funding is $47. 8 million (this includes the $5 M enhancement in 2011) – Dedicated funding from tobacco taxes to tobacco control – Public health funding from tobacco settlements § Divestment of investments § Products: prohibit new products, plain packaging, restrict water pipes § Price: Increase price / tax; Anti-contraband public education § Promotion: Adult rates for movies and video games with tobacco imagery

TSAG Implementation Strategies awaiting commencement / uncertain status: § Tobacco Growing: Work with partners to reduce tobacco production over time (licenses, acreage, ceilings) § Protection • Amend SFO to eliminate smoking in patios, hotels, doorways, playgrounds (local public health action re bylaws – 75+ outdoor smoking amendments) • Smoke-free Multiunit Dwellings: – Amend Residential Tenancies Act to allow smoke-free MUDs a material term of leases (local municipal initiatives – now 75 + smoke-free community housing buildings in Ontario) – Tax credits for smoke-free affordable housing

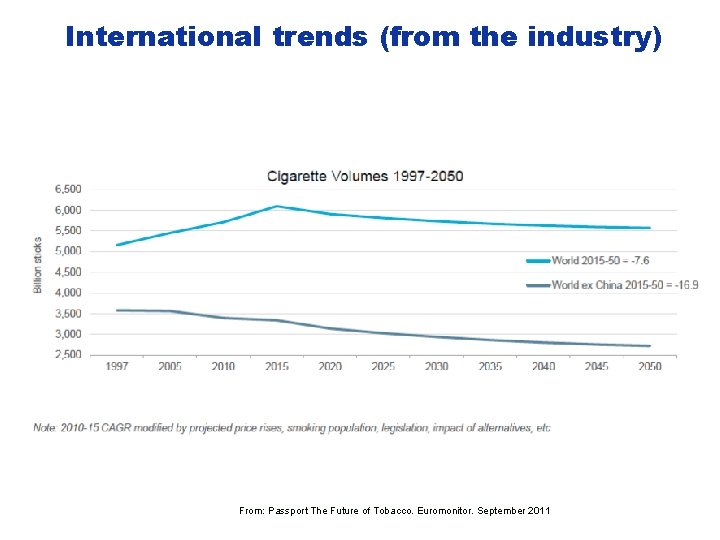

International trends (from the industry) “Although China will pay lip service to tobacco control, population growth is forecast to mitigate any fall in smoking prevalence, even in the long term. ” From: Passport The Future of Tobacco. Euromonitor. September 2011

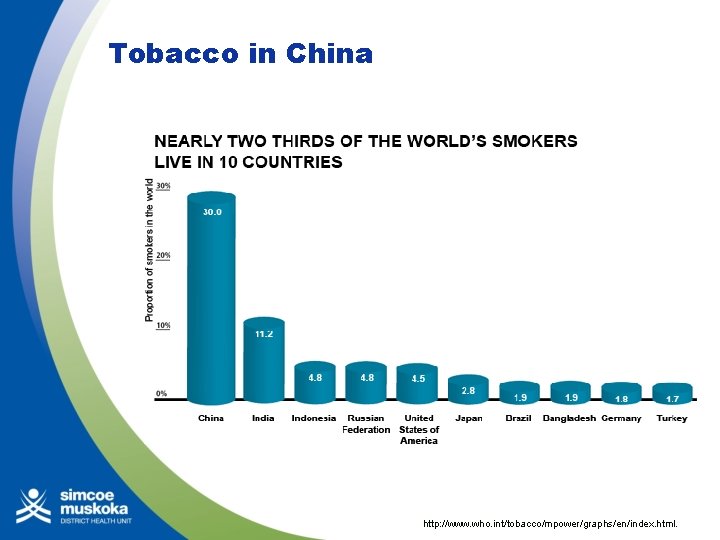

Tobacco in China http: //www. who. int/tobacco/mpower/graphs/en/index. html.

Tobacco Use in the Caribbean At least 20% of the general population of the Caribbean has consumed tobacco at some point during their life More than a 10% of the population of the English-speaking Caribbean are current consumers, meaning they have consumed tobacco during the last month. A 2010 comparative analysis of student drug use in 12 Caribbean countries - Lifetime prevalence rates of tobacco use indicates that : - Grenada has the highest reported rate - 34. 53% - Suriname - 33. 06% - Dominica - 30. 69% - T&T - 28. 86% World Drug Report 2010 Courtesy of Jeffrey Edwards MD, Doctorate of Public Health candidate, University of the West Indies

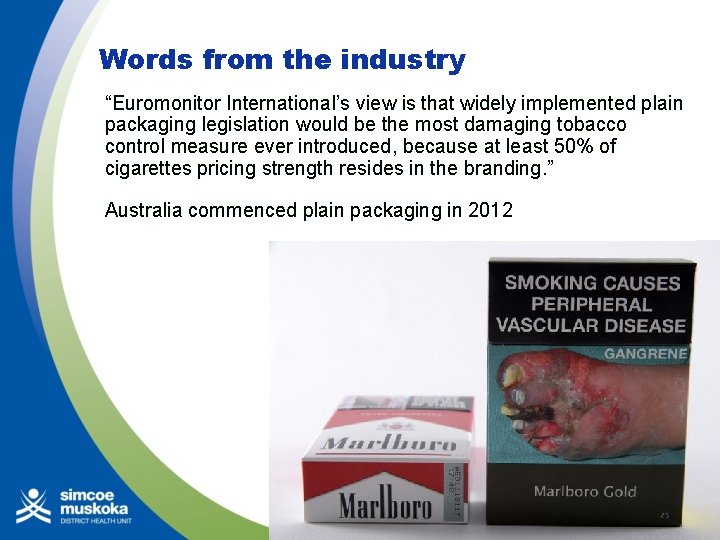

Words from the industry “Euromonitor International’s view is that widely implemented plain packaging legislation would be the most damaging tobacco control measure ever introduced, because at least 50% of cigarettes pricing strength resides in the branding. ” Australia commenced plain packaging in 2012

Some observations from tobacco’s history • The power of industry: • An industry capable of making great profits at the expense of 10 years of the life expectancy for most of the population for most of a century • Once established, has enormous influence, delaying effective government action for decades • Foresight is possible, but action has been delayed: • The solutions can be logically deduced (but delayed in implementation). Some identified early (the 1960 s) the range of tobacco-control strategies required • Research is the beginning – determination, the end • Research is the essential starting point to turning things around – but is not enough. The courage and determination of many people in and out of the public health community over many years has been critical for change

What next? What is our end-game? Provincially? Internationally? How should local public health be positioned in this? • We have achieved much – and much remains to be achieved • TSAG recommendations are excellent – but much remains to be implemented • Expect many years of dedicated work to come • Expect (and work to overcome) setbacks and delays • Know that the industry still has enormous resources and influence – but also that the peak and decline in tobacco internationally will come

What are the transferable lessons? § There are parallels with other “unhealthy commodities”. ØUnhealthy foods ØInadequate physical activity ØUnsafe alcohol consumption ØVinyl chloride, asbestos, cars § Underlying common strategies of unhealthy commodity industries: ØSeek to bias research findings ØCo-opt policy makers and health professionals ØLobby politicians and public officials to oppose public regulation ØEncourage voters to oppose public health regulation ØTo deflect criticism - promote actions outside their areas of expertise § Conclusion - there is little objective evidence that public–private partnerships deliver health benefits Sources: Profits and pandemics: prevention of harmful effects of tobacco, alcohol, and ultra-processed food and drink industries. Rob Moodie et al, on behalf of The Lancet NCD Action Group - Lancet 2013; 381: 670– 79 Why corporate power is a public health priority. Gerard Hastings. BMJ August 2012: 345

What are the transferable lessons? § There are transferable strategies. § Healthy Kids Panel recommendations (re healthy weights in children) § National Alcohol Strategy recommendations § Commonly recommended strategies § § § Whole of government approach Government outreach and funding to partners Safe / healthy consumption standards Restrictions on marketing / product placement / outlet density (eg. maintain the LCBO) Product content disclosure / signage Public awareness raising School programs Surveillance and public reporting Healthcare interventions Protection of vulnerable populations / poverty reduction / youth Legislation enforcement Ongoing research

Final Thoughts § Tobacco is the industry-driven cause of the greatest loss of life in modern history § We have made very difficult and slow progress – but indeed we have progressed § Much remains to be achieved in Ontario § Things will get worse before they get better internationally § There are transferable insights regarding other industry-driven challenges to public health

- Slides: 68