GEOG 2 Human Geography People Place and Power

- Slides: 45

GEOG 2 – Human Geography (People, Place and Power) Professor: Dr. Jean-Paul Rodrigue Topic 6 – Political Geography A – Region: The Nation-State B – Mobility and Political Geography C – Supranationalism and transnationality D – Physical geography and the state E – National Cultural Landscape Hofstra University, Department Global Studies & Geography Hofstra University, of of Global Studies & Geography

What is political geography? ■ The study of the organization and distribution of political phenomena in their areal expression ■ The country unit, also called state is often the unit of analysis ■ Consider higher (multinational agreements) and lower (regional / local organization) geographical scale of analysis © Dr. Jean-Paul Rodrigue

A – REGION: THE NATION-STATE The concept of nation-states, the forces that shape political territory, and the regional characteristics of electoral politics. © Dr. Jean-Paul Rodrigue

A World of Nation-States ■ States • World divided in about 200 independent countries. • Historically, the state has taken a variety of forms. • City-states (Greece). • Dynastic states (China). • Feudal states (Europe). • Modern states are independent political units with a centralized authority that claims exclusive legal, political, and economic jurisdiction over defined boundaries. ■ Sovereignty • Every state possesses the sole authority over the land people within its boundaries. • From the political system to land resource use decisions. • Referred to as internal sovereignty. • Under international law, states recognize each other’s boundaries, © Dr. Jean-Paul Rodrigue

The Idea of the Nation-State ■ Self-determination • The freedom of culturally distinct groups to govern themselves in their own territories. • To form a nation; a community of people bound to a homeland having a common identity based on shared cultural traits such as language, ethnicity, and religion. • The geographic boundaries of a nation (a people and its culture) would be identical to the territorial boundaries of the state (governance and authority). ■ Nationalism • Historically recent and learned emotional attachment. • The individual derives identity from a sense of belonging to a nation. • Geography and cultural identity are linked in the concepts of nationalism and the nation-state. © Dr. Jean-Paul Rodrigue

The Idea of the Nation-State ■ Territoriality • Territorial claims are consolidated through the establishment of precise boundaries. • Border: A clearly demarcated line that marks both the limits of a territory and the division between territories. • Divide the world into nation-states. • Divide nation-states into subnational territories, such as counties or provinces. • A concept mostly of European origin. Explain the concept of nation-state, sovereignty and territoriality. © Dr. Jean-Paul Rodrigue

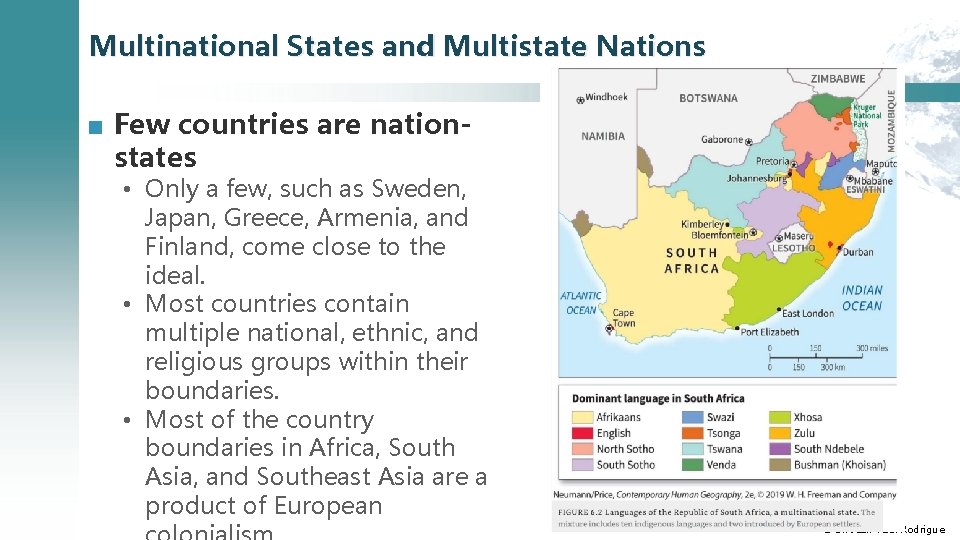

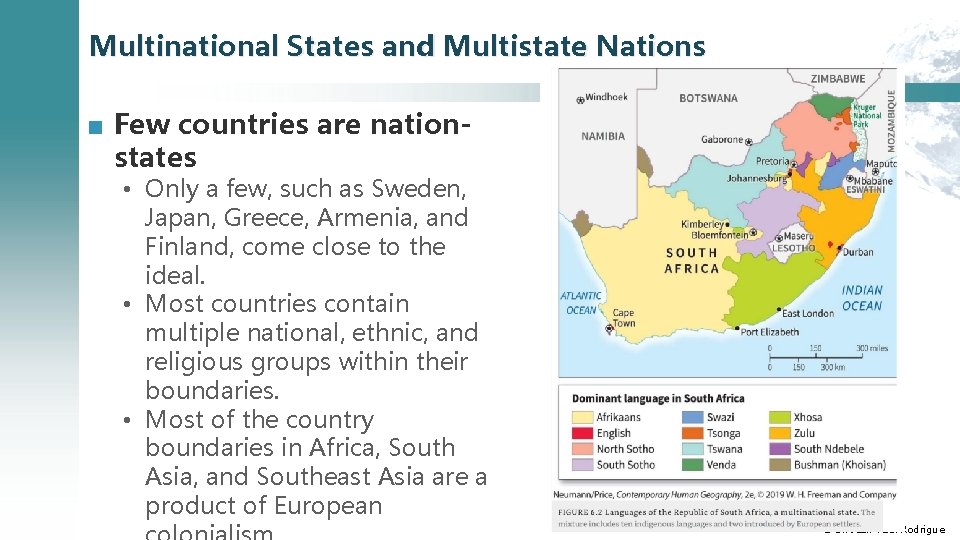

Multinational States and Multistate Nations ■ Few countries are nationstates • Only a few, such as Sweden, Japan, Greece, Armenia, and Finland, come close to the ideal. • Most countries contain multiple national, ethnic, and religious groups within their boundaries. • Most of the country boundaries in Africa, South Asia, and Southeast Asia are a product of European © Dr. Jean-Paul Rodrigue

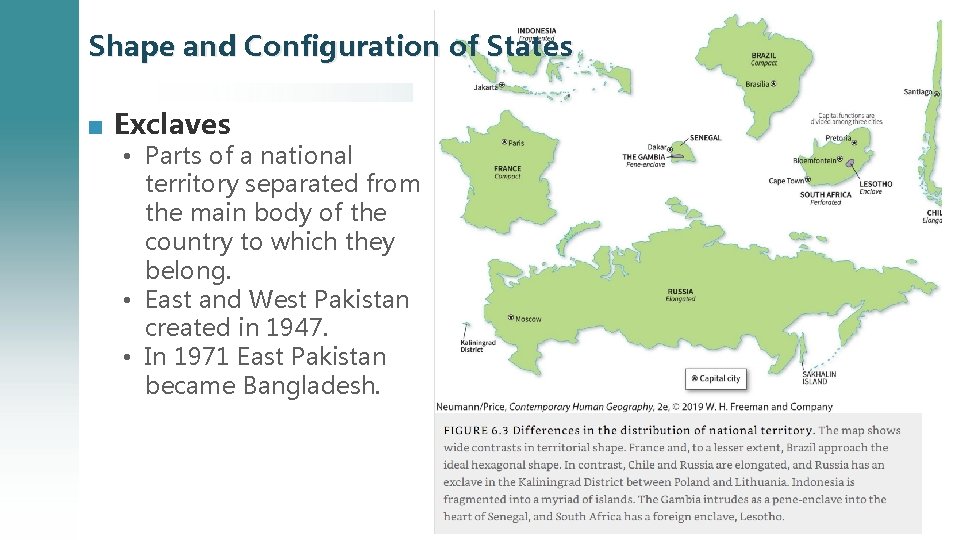

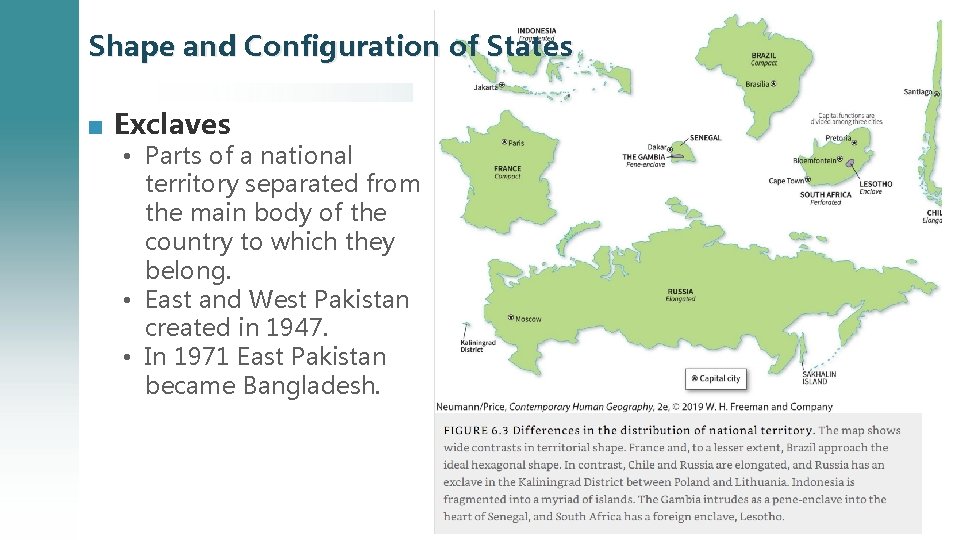

Shape and Configuration of States ■ Challenges to centralized authority • The more compact the territory, the easier the governance. • Circular or hexagonal forms maximize compactness, allow for shorter communication lines, and minimize the amount of border to be defended. • No country enjoys this abstract ideal of compactness; France and Brazil come close. ■ Enclaves • Territory surrounded by a country but not ruled by it. • Can be either self-governing (Lesotho; The Gambia) or an exclave of another country (Kaliningrad). • Presence can pose problems for both the enclave and the surrounding country. • Differences between an enclave and a landlocked country. © Dr. Jean-Paul Rodrigue

Shape and Configuration of States ■ Exclaves • Parts of a national territory separated from the main body of the country to which they belong. • East and West Pakistan created in 1947. • In 1971 East Pakistan became Bangladesh. © Dr. Jean-Paul Rodrigue

Types of Boundaries What are the main types of boundaries and provide some examples. ■ Natural boundaries • Follow some feature of the landscape, such as a river or mountain ridge. • The Pyrenees lie between Spain and France, and the Rio Grande serves as part of the border between Mexico and the United States. ■ Ethnographic boundaries • Drawn based on one or more cultural traits, usually a particular ethnicity, language spoken, or religion practiced. • Can be found throughout Western Europe. ■ Geometric boundaries • Regular, often perfectly straight lines drawn without regard for physical or cultural features of the area. • The U. S. – Canada border west of the Lake of the Woods (about 93 ° west longitude) is a geometric boundary. © Dr. Jean-Paul Rodrigue

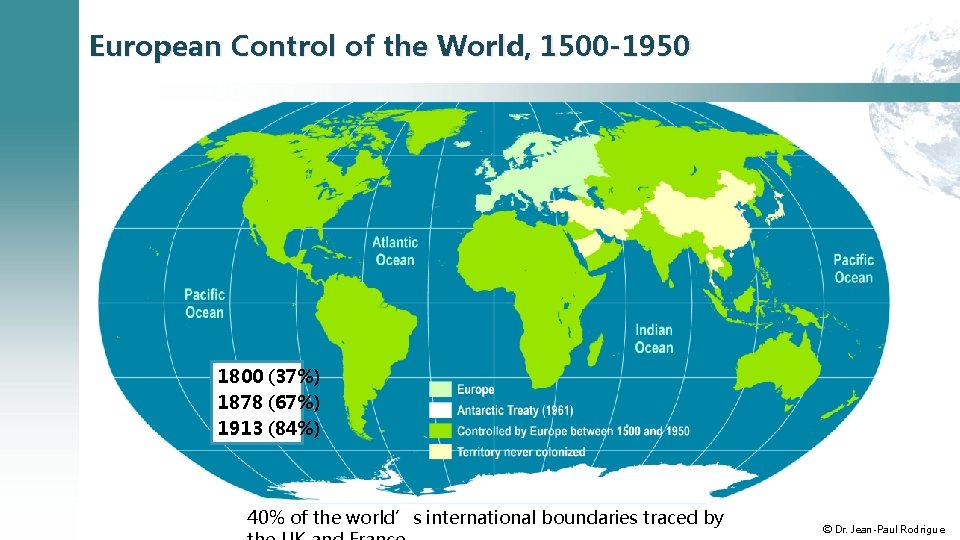

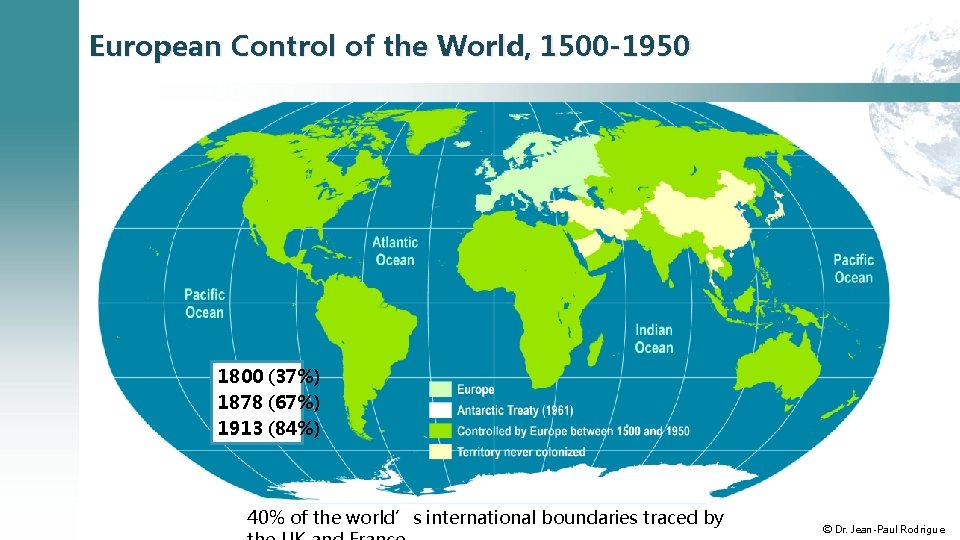

European Control of the World, 1500 -1950 1800 (37%) 1878 (67%) 1913 (84%) 40% of the world’s international boundaries traced by © Dr. Jean-Paul Rodrigue

Centripetal forces: Promoting state cohesion ■ Nationalism • Promoted by state institutions to maintain coherence. • Educational system; holidays, museums, national parks and monuments. ■ Unifying institutions ■ Organization and administration ■ Transportation and communication © Dr. Jean-Paul Rodrigue

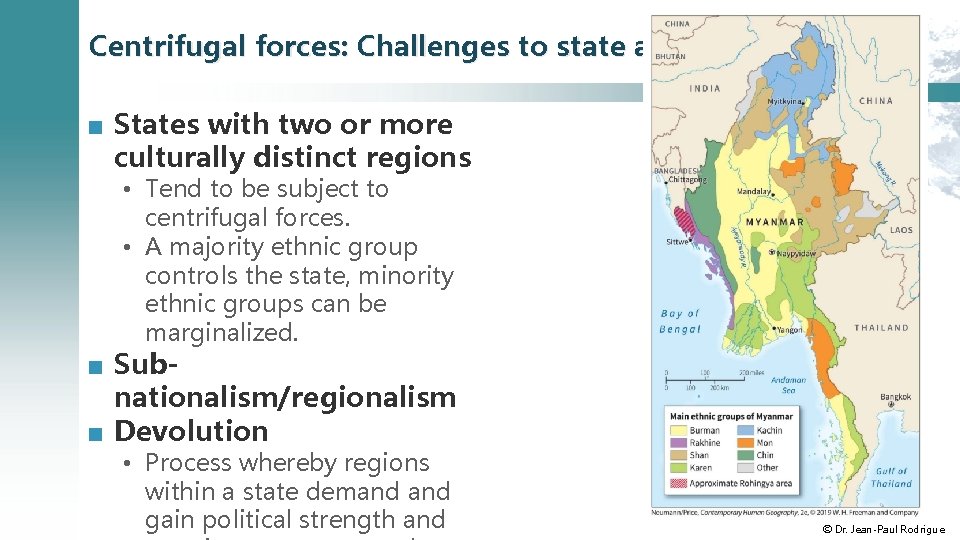

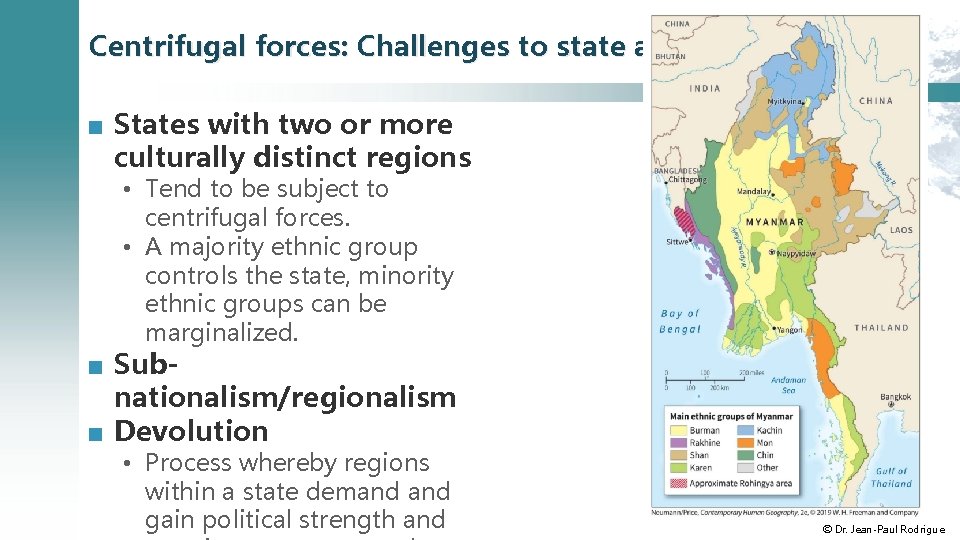

Centrifugal forces: Challenges to state authority ■ States with two or more culturally distinct regions • Tend to be subject to centrifugal forces. • A majority ethnic group controls the state, minority ethnic groups can be marginalized. ■ Subnationalism/regionalism ■ Devolution • Process whereby regions within a state demand gain political strength and © Dr. Jean-Paul Rodrigue

Separatist and Irredentist Movements ■ Separatist movements • Centrifugal forces can sometimes generate separatist movements. • Ethnic separatism promotes the separation of an ethnically distinct group to form a politically autonomous region within an existing state or to secede and form a new nation-state. • Yugoslavia between 1992 and 2008; Seven new culturally-based nation-states. • East Timor seceded from Indonesia in 2002. • South Sudan separated in 2011. ■ Irredentist movements • The claim to territory in another country based on ethnic affiliations and historic borders. • Germany claiming Austria and parts of Czechoslovakia before WWII. Discuss centripetal and centrifugal forces • Russian annexation of the Crimean Peninsula (2014). in state cohesion. © Dr. Jean-Paul Rodrigue

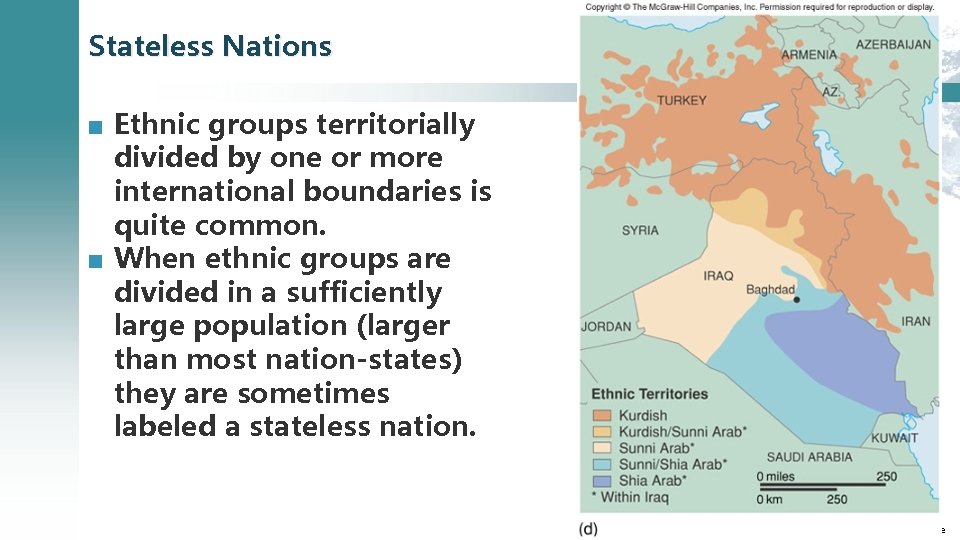

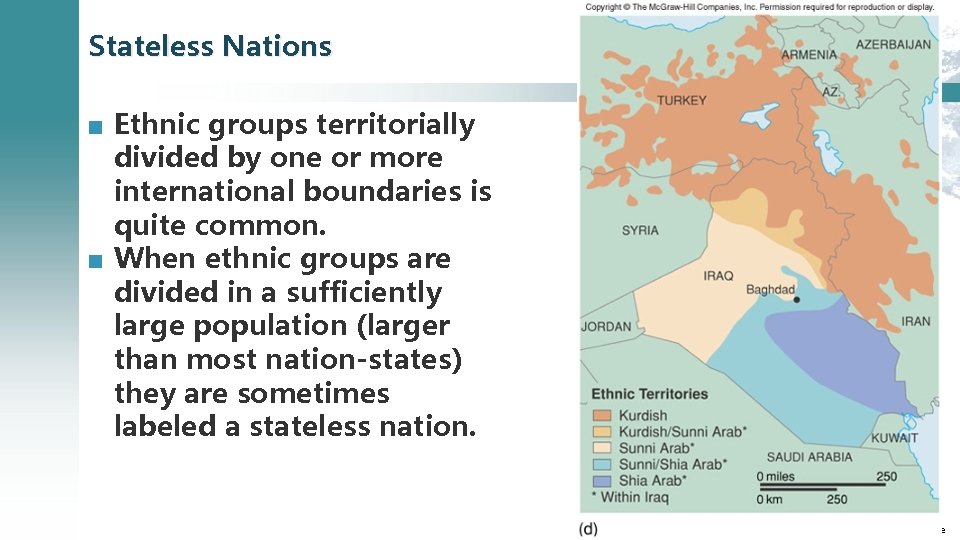

Stateless Nations ■ Ethnic groups territorially divided by one or more international boundaries is quite common. ■ When ethnic groups are divided in a sufficiently large population (larger than most nation-states) they are sometimes labeled a stateless nation. © Dr. Jean-Paul Rodrigue

Internal Organization of Territory ■ Unitary state • • • Power concentrated centrally. Little or no authority vested in subnational political units. All major decisions come from the central government. Policies are applied uniformly throughout the national territory. France and China. ■ Federal state • Disperses significant authority among subnational units such as provinces and states. • United States, Canada, Germany, Australia, and Switzerland. • More latitude for subnational self-rule. • Can help reduce centrifugal forces and undermine public support for separatist movements. © Dr. Jean-Paul Rodrigue

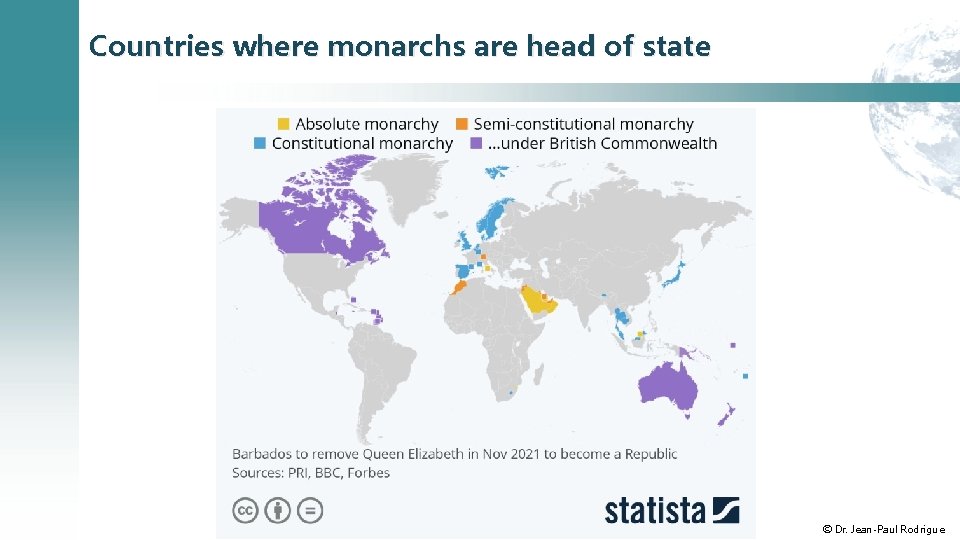

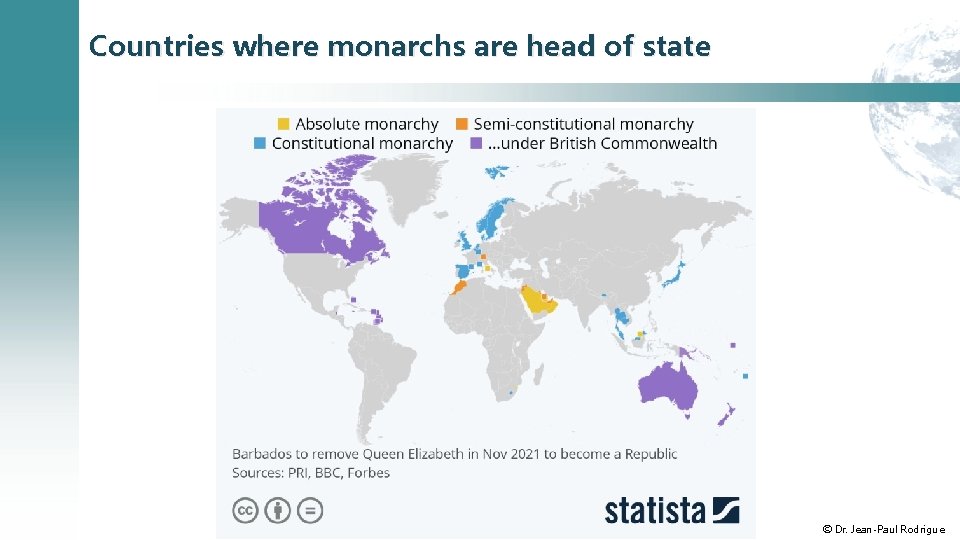

Countries where monarchs are head of state © Dr. Jean-Paul Rodrigue

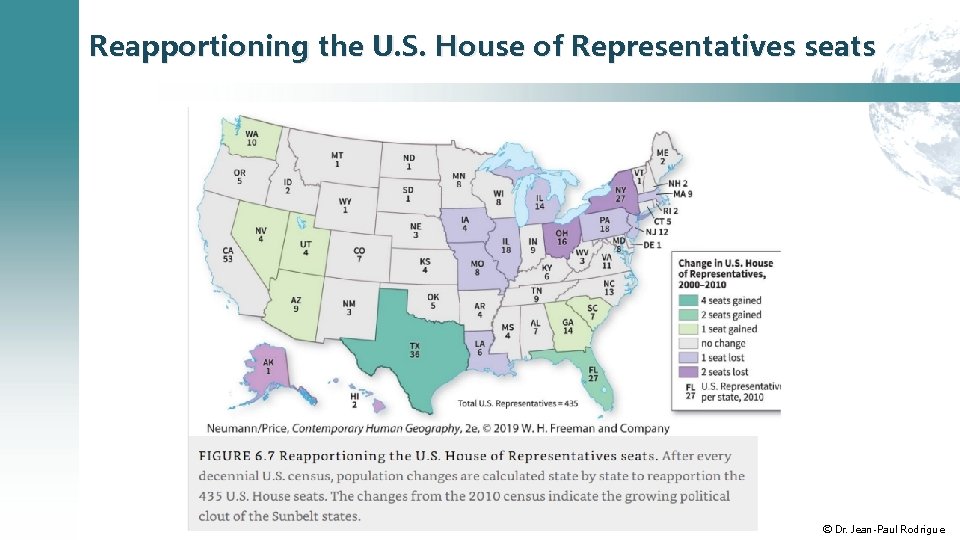

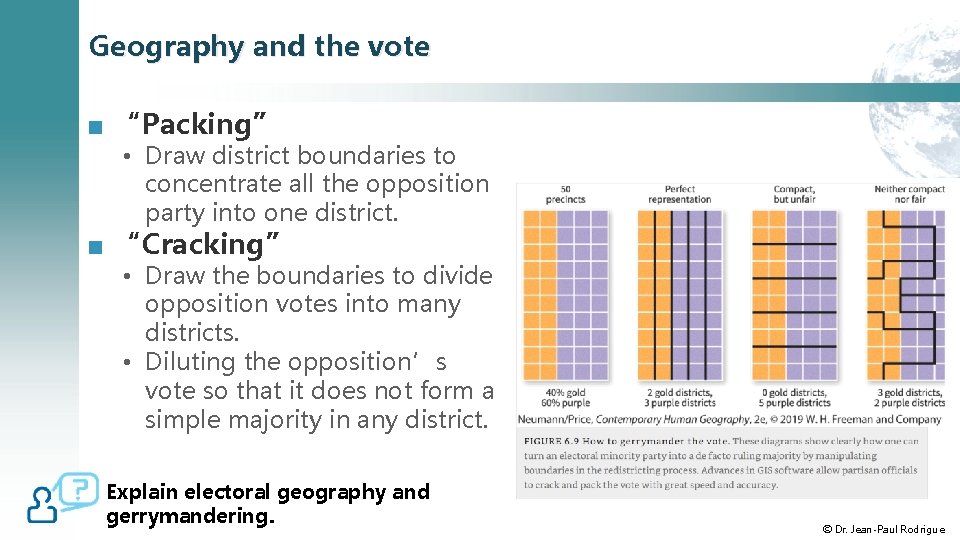

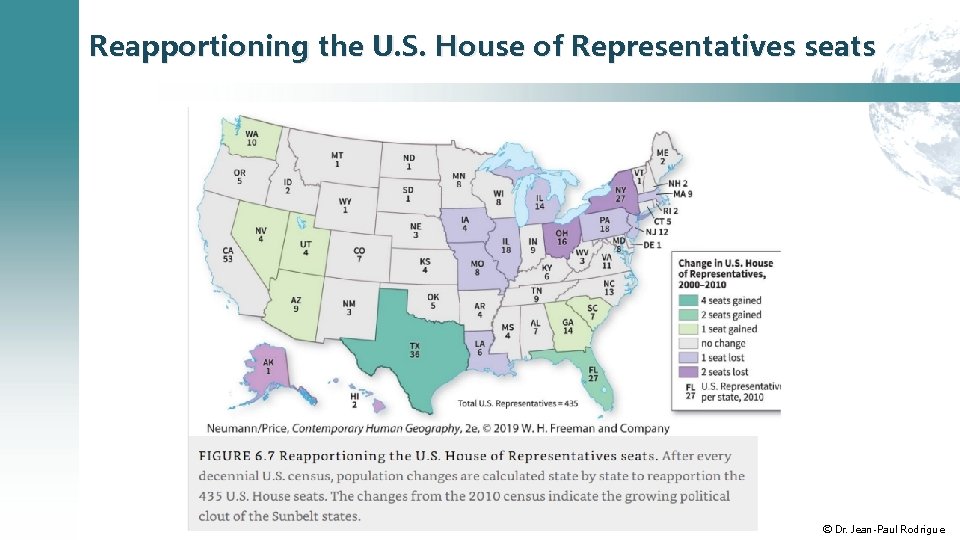

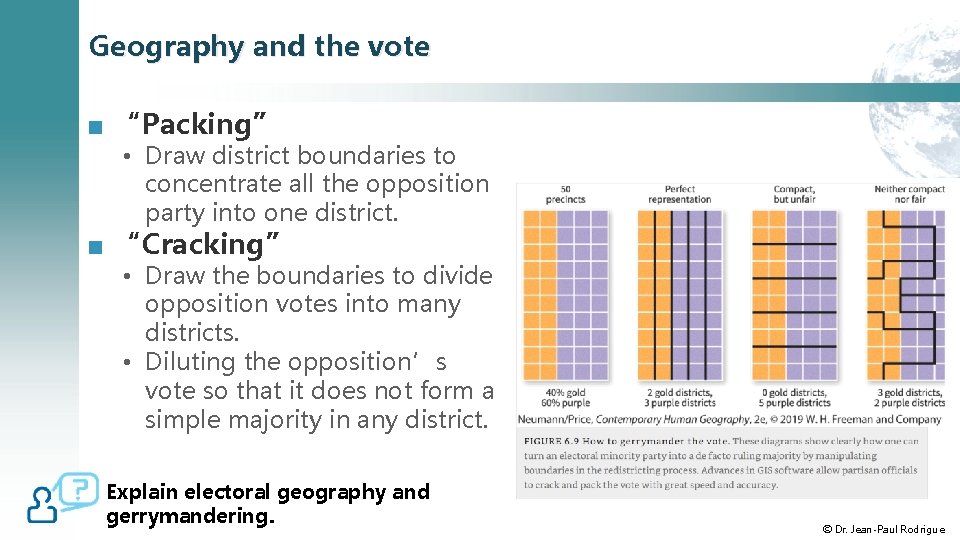

Geography and the vote ■ Electoral geography • Analyzes the geographic character of political preferences and how geography can shape voting outcomes. ■ Gerrymandering • Ways that geography can shape voting outcomes. • Division into voting districts or precincts. • Reapportionment: • Process by which the 435 seats in the U. S. House of Representatives are divided proportionately by population among the 50 states. ■ Political redistricting • New boundaries for congressional districts. • Establish voting areas of equal population. • Increase or reduce the number of districts depending on the change in total population. © Dr. Jean-Paul Rodrigue

Reapportioning the U. S. House of Representatives seats © Dr. Jean-Paul Rodrigue

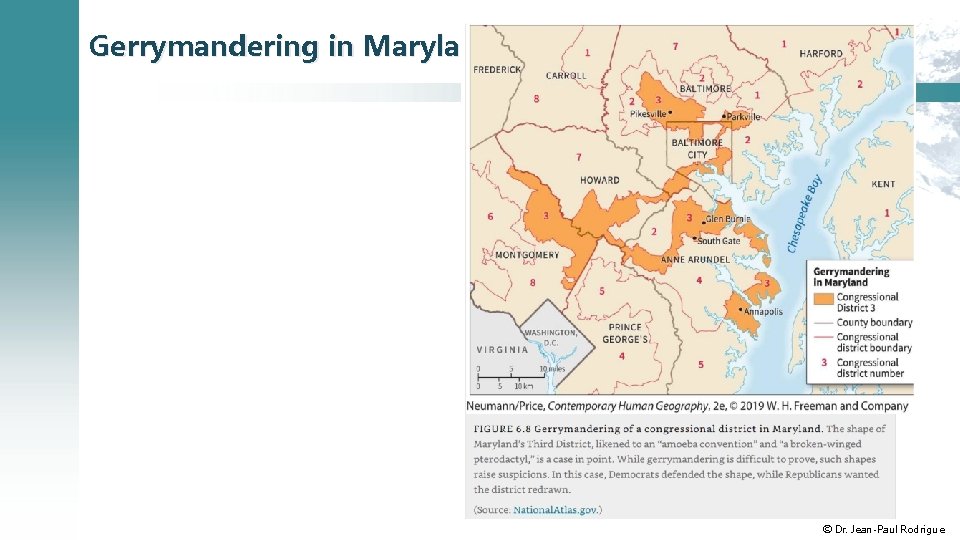

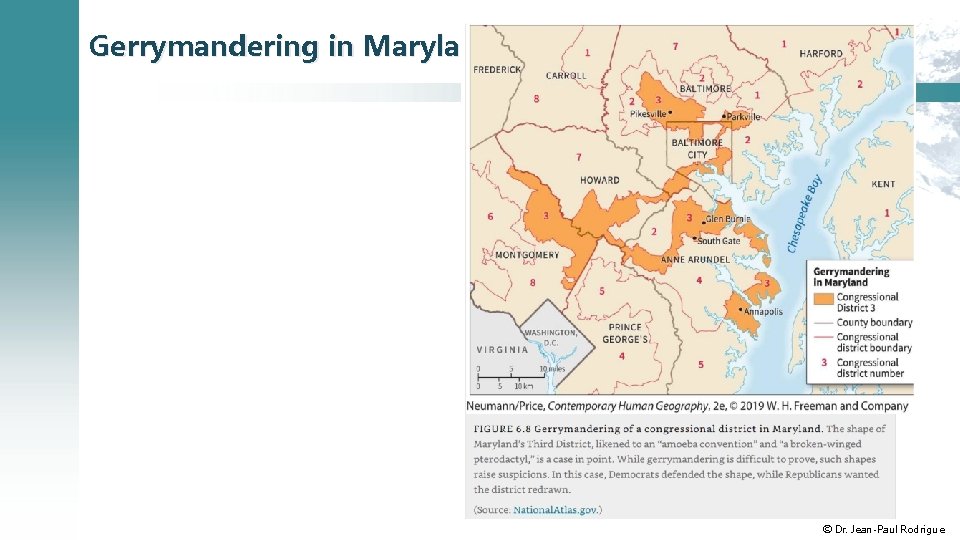

Gerrymandering in Maryland © Dr. Jean-Paul Rodrigue

Geography and the vote ■ “Packing” • Draw district boundaries to concentrate all the opposition party into one district. ■ “Cracking” • Draw the boundaries to divide opposition votes into many districts. • Diluting the opposition’s vote so that it does not form a simple majority in any district. Explain electoral geography and gerrymandering. © Dr. Jean-Paul Rodrigue

B – MOBILITY AND POLITICAL GEOGRAPHY How mobility influences political geography, including the spatial diffusion of political authority and innovation, the displacement effects of violent political conflict, and the role of the Internet. © Dr. Jean-Paul Rodrigue

The diffusion of political authority ■ Formed states • Several independent states emerged fully formed. • Most the outcome of colonialism (Latin America and Sub-Saharan Africa). • Outcome of a treaty at the end of a conflict (e. g. partition of Poland in the 18 th century and reconstitution after WWI). ■ Outward expansion • Many of the oldest states expanded outward from an initial center. • The ancient power center remains the country’s single most important region. • The capital city and the cultural and economic heart of the nation. • Major transportation infrastructure often built to favor expansion (transcontinental, trans-Siberian). © Dr. Jean-Paul Rodrigue

Diffusion of Russian political control © Dr. Jean-Paul Rodrigue

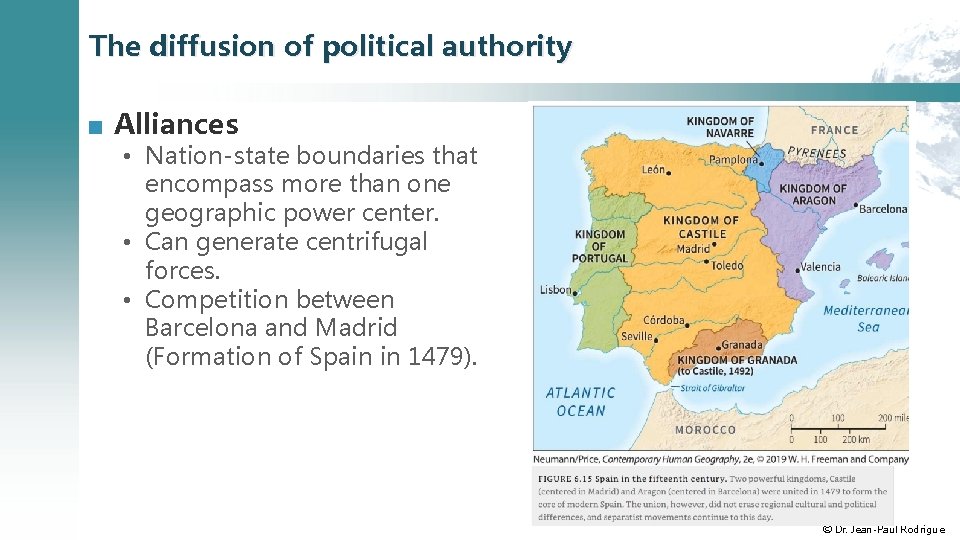

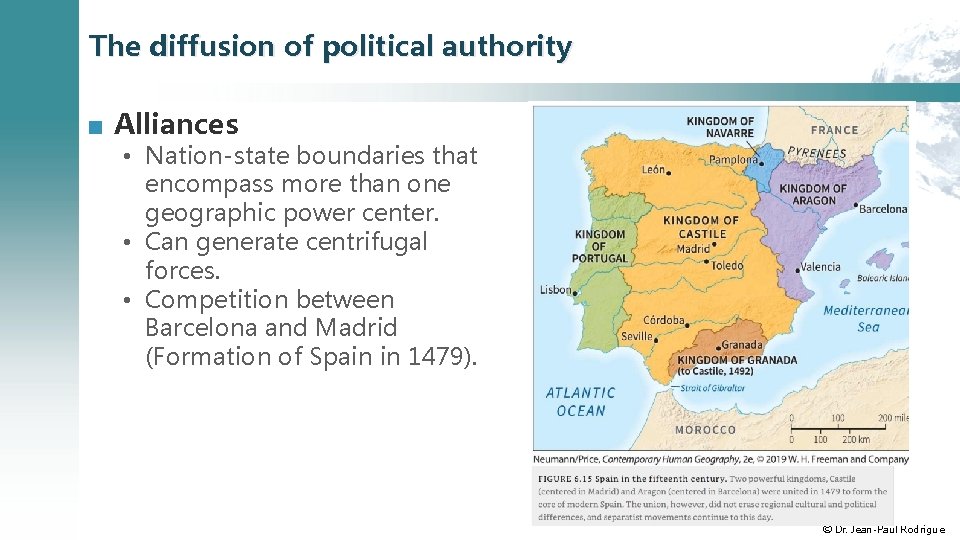

The diffusion of political authority ■ Alliances • Nation-state boundaries that encompass more than one geographic power center. • Can generate centrifugal forces. • Competition between Barcelona and Madrid (Formation of Spain in 1479). © Dr. Jean-Paul Rodrigue

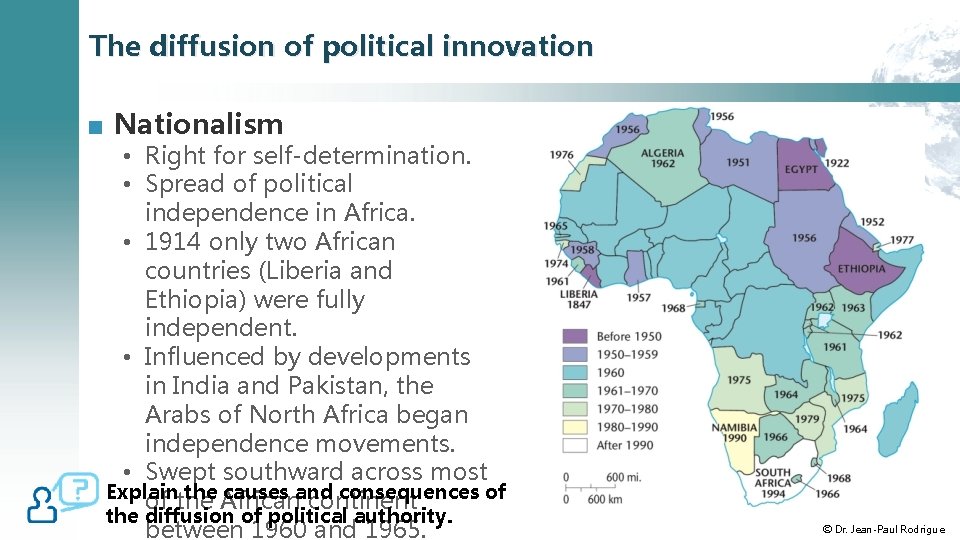

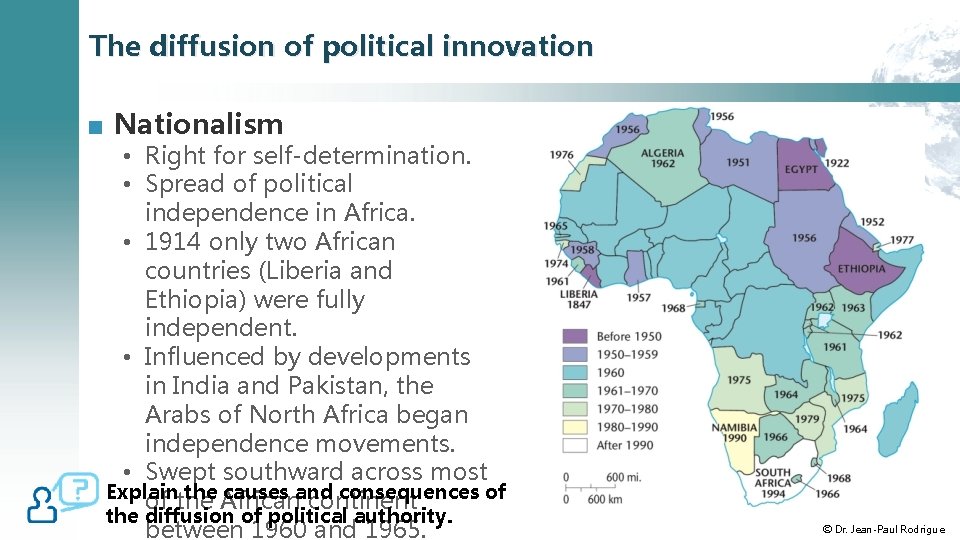

The diffusion of political innovation ■ Nationalism • Right for self-determination. • Spread of political independence in Africa. • 1914 only two African countries (Liberia and Ethiopia) were fully independent. • Influenced by developments in India and Pakistan, the Arabs of North Africa began independence movements. • Swept southward across most Explain the African causes and consequences of of the continent the diffusion of political authority. between 1960 and 1965. © Dr. Jean-Paul Rodrigue

Forced mobility of conflicts ■ Ethnic cleansing • Forced removal of an ethnic group by another ethnic group to create ethnically homogeneous territories. • Behind many recent forced international migrations. • Yugoslavia, Rwanda, Darfur (Sudan), Myanmar (Rohingya). ■ Armed conflict • Most refugees fleeing armed conflict areas. • Internally and internationally displaced. • Syrian conflict. ■ International response • Asylum countries. • Refugee camps (in less developed countries). • Role of the United Nation High Commissariat for Refugees. © Dr. Jean-Paul Rodrigue

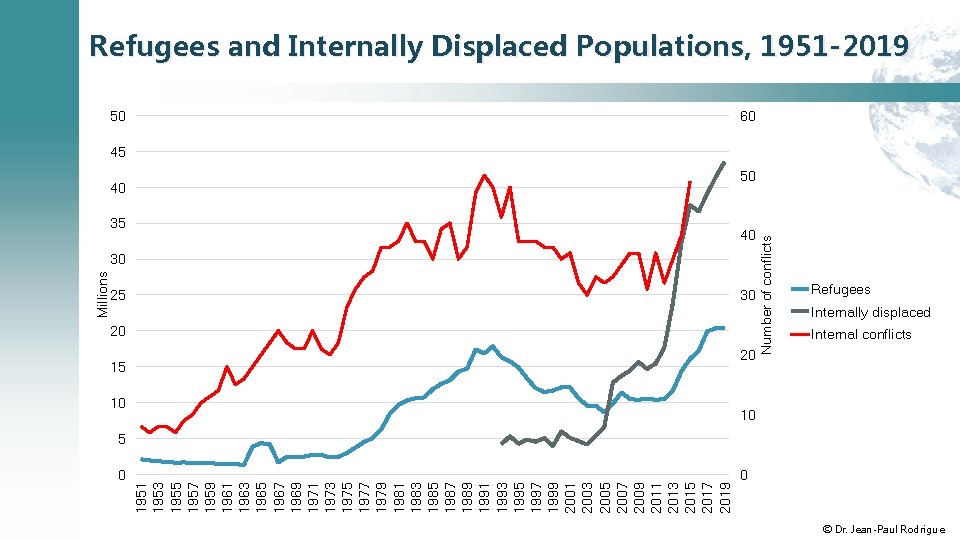

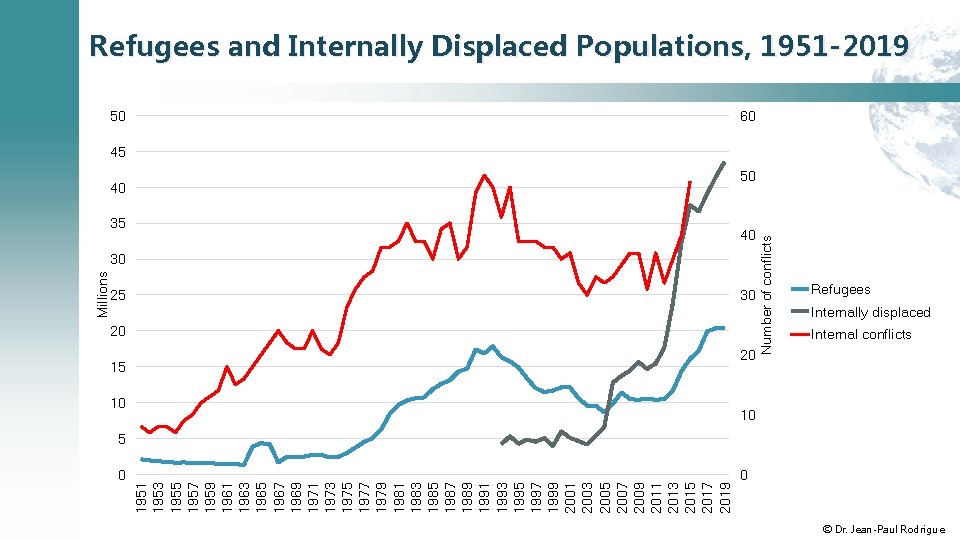

0 1951 1953 1955 1957 1959 1961 1963 1965 1967 1969 1971 1973 1975 1977 1979 1981 1983 1985 1987 1989 1991 1993 1995 1997 1999 2001 2003 2005 2007 2009 2011 2013 2015 2017 2019 Millions 50 40 35 40 30 25 30 20 15 20 10 Number of conflicts Refugees and Internally Displaced Populations, 1951 -2019 60 45 50 Refugees Internally displaced Internal conflicts 10 5 0 © Dr. Jean-Paul Rodrigue

Transborder mobility in cyberspace ■ A new “space” • The Internet and various social media have facilitated the movement of goods, money, and ideas across international borders in unprecedented new ways. • Make borders seem more porous, even nonexistent. • Gathering information (spying) and hacking. • Implications for territorial sovereignty. ■ Maintaining sovereignty • How can countries impose their laws, defend their cultural norms, and maintain sovereignty in the Internet age? • Restrict access to technological hardware (computers, cell phones); not very effective. • Control access to the flow of information. • Block access to specific sites. © Dr. Jean-Paul Rodrigue

C – SUPRANATIONALISM AND TRANSNATIONALITY The effects of globalization on sovereignty, supranationalism, and transnationality. © Dr. Jean-Paul Rodrigue

Supranationalism ■ Supranationalism • A group of nation-states relinquish some sovereign rights to a larger -scale political body. • Formation of supranational organizations. • Establish cooperation for mutual political, military, economic, or cultural gain. ■ Origins • Bretton Woods Agreement (1944). • Formation of the World Bank and International Monetary Fund. ■ Trading blocs • Multi-country agreement that reduces or eliminates customs duties and import tariffs. • Promote the freer flow of goods and services across international borders. © Dr. Jean-Paul Rodrigue

Selected Supranational Organizations © Dr. Jean-Paul Rodrigue

The condition of transnationality ■ Transnationalism • The experience of living and working in more than one country. • Can produce new and distinct cultural identities. • Sometimes used synonymously with globalization to refer to economic, political, or cultural processes operating across international borders. • “Expats”; particularly in global cities. Explain the differences between supranationalism and transnationalism. © Dr. Jean-Paul Rodrigue

D – PHYSICAL GEOGRAPHY AND THE STATE The complex interactions of politics and physical geography, including the state’s role in land management, the heartland theory of world geopolitics. © Dr. Jean-Paul Rodrigue

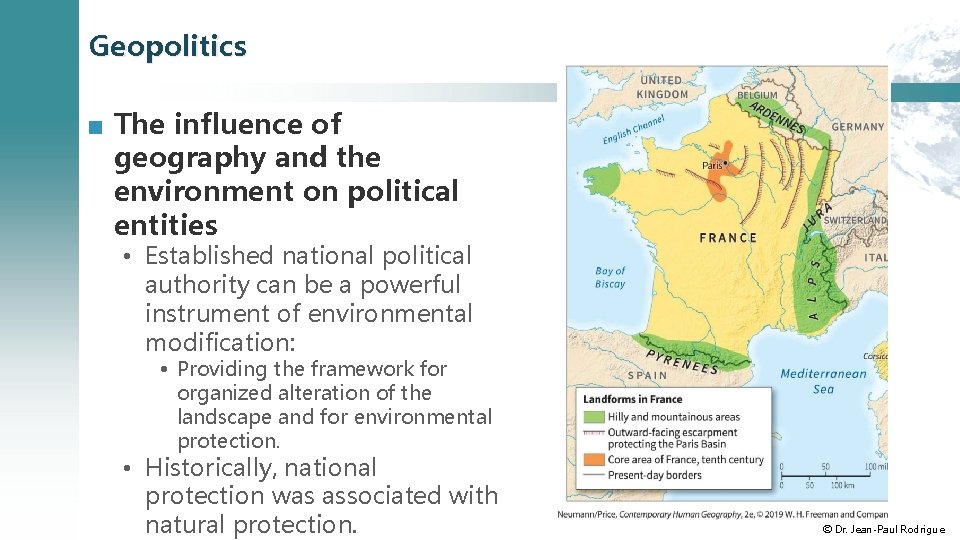

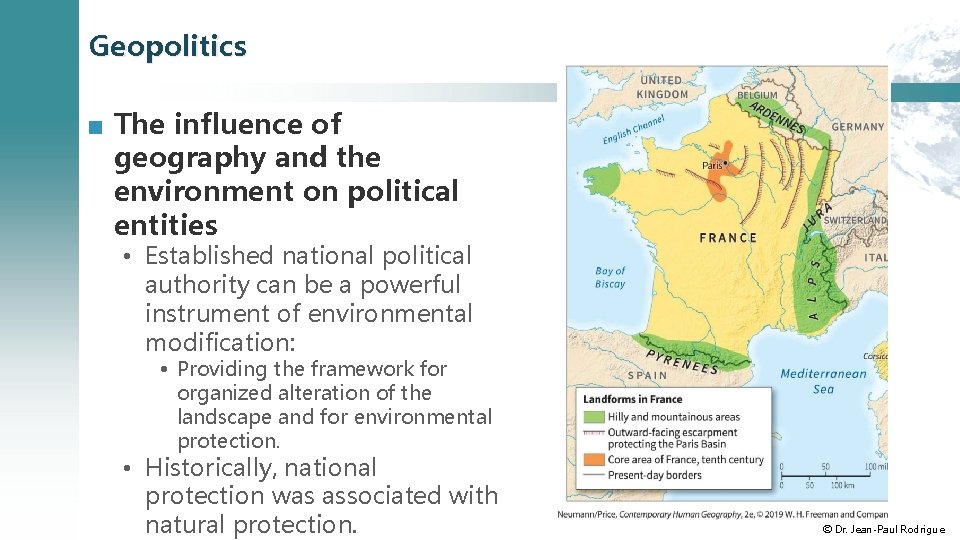

Geopolitics ■ The influence of geography and the environment on political entities • Established national political authority can be a powerful instrument of environmental modification: • Providing the framework for organized alteration of the landscape and for environmental protection. • Historically, national protection was associated with natural protection. © Dr. Jean-Paul Rodrigue

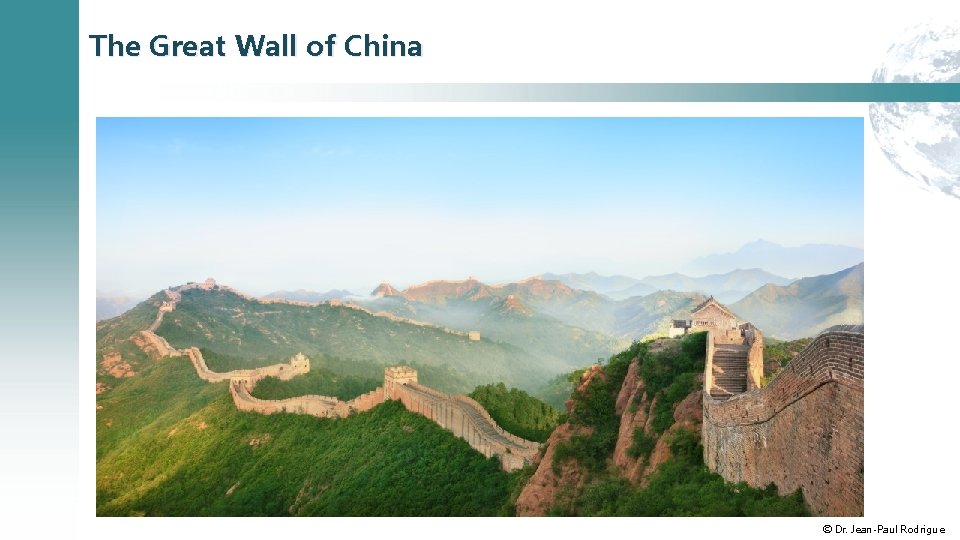

The Great Wall of China © Dr. Jean-Paul Rodrigue

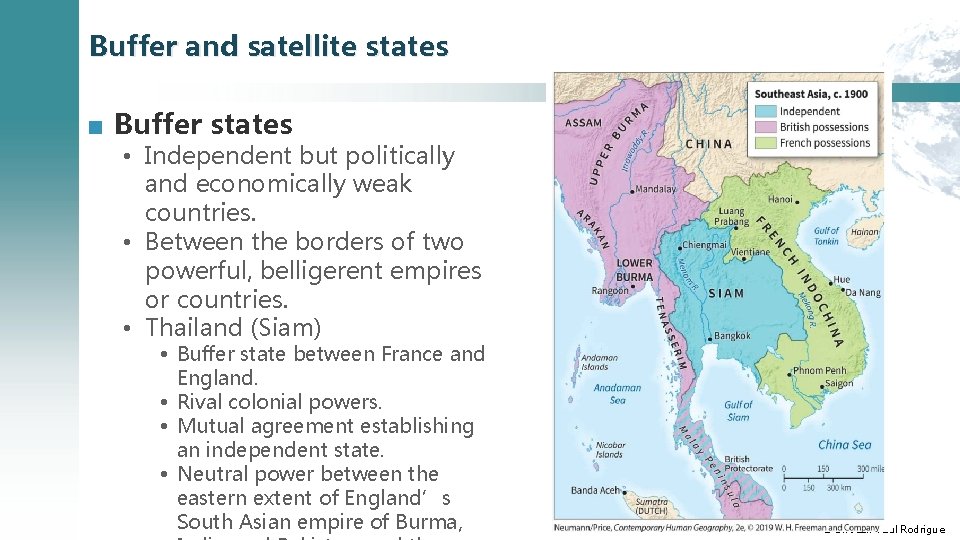

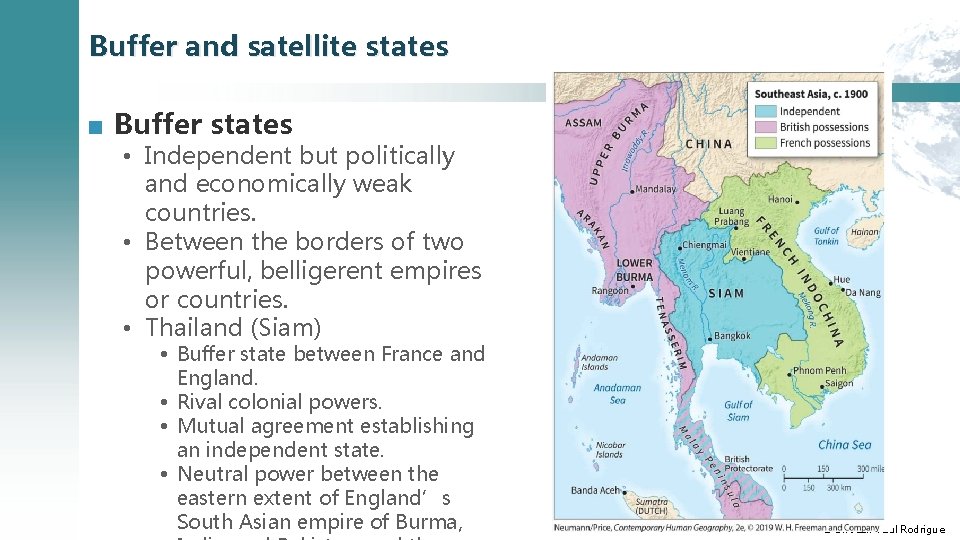

Buffer and satellite states ■ Buffer states • Independent but politically and economically weak countries. • Between the borders of two powerful, belligerent empires or countries. • Thailand (Siam) • Buffer state between France and England. • Rival colonial powers. • Mutual agreement establishing an independent state. • Neutral power between the eastern extent of England’s South Asian empire of Burma, © Dr. Jean-Paul Rodrigue

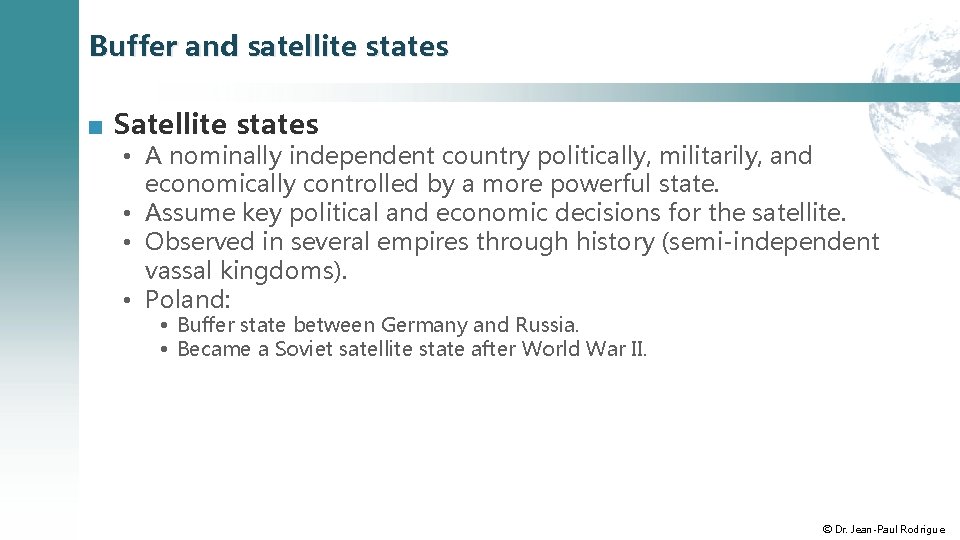

Buffer and satellite states ■ Satellite states • A nominally independent country politically, militarily, and economically controlled by a more powerful state. • Assume key political and economic decisions for the satellite. • Observed in several empires through history (semi-independent vassal kingdoms). • Poland: • Buffer state between Germany and Russia. • Became a Soviet satellite state after World War II. © Dr. Jean-Paul Rodrigue

E – NATIONAL CULTURAL LANDSCAPE The effects of national laws, international borders, and national monuments on the cultural landscape. © Dr. Jean-Paul Rodrigue

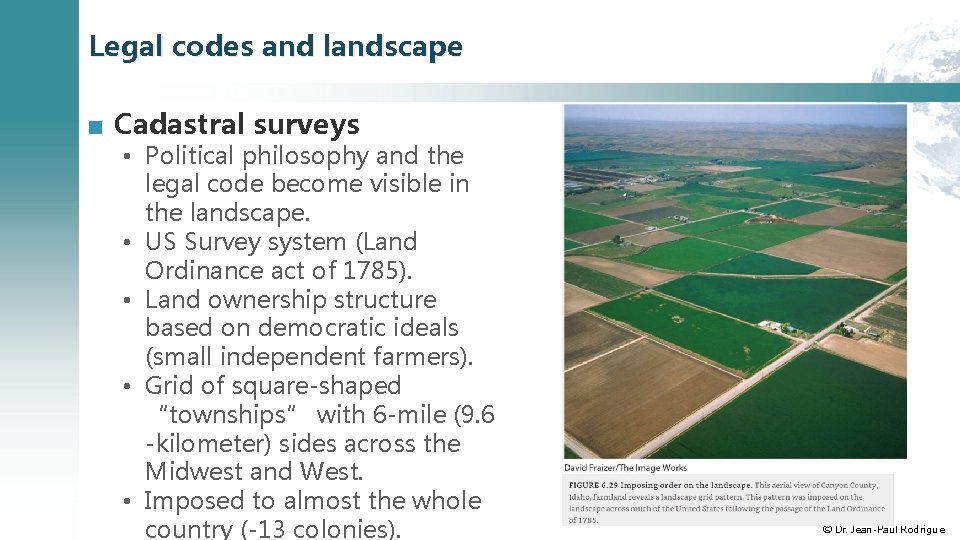

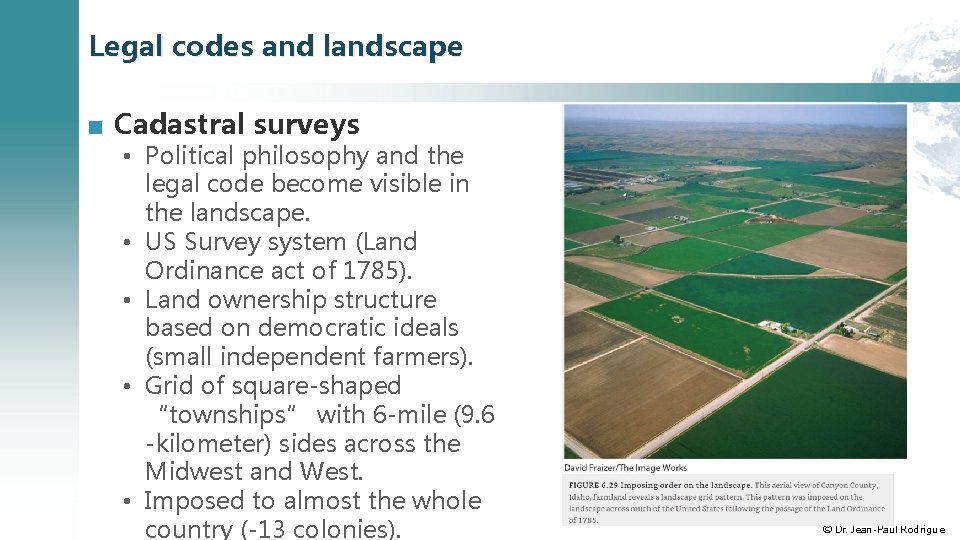

Legal codes and landscape ■ Cadastral surveys • Political philosophy and the legal code become visible in the landscape. • US Survey system (Land Ordinance act of 1785). • Land ownership structure based on democratic ideals (small independent farmers). • Grid of square-shaped “townships” with 6 -mile (9. 6 -kilometer) sides across the Midwest and West. • Imposed to almost the whole country (-13 colonies). © Dr. Jean-Paul Rodrigue

Border landscapes ■ Demarcated political boundaries • Visible landscapes. • Political borders are usually most visible where restrictions limit the movement of people between neighboring countries. • Sometimes lined with cleared strips, barriers, pillboxes, tank traps, and other obvious defensive installations. • Some international borders, such as that between Tanzania and Kenya in East Africa, that are unfortified, thinly policed, and for many miles invisible in the landscape. • Temporal variations (past or current boundaries). Provide some examples of border landscapes. © Dr. Jean-Paul Rodrigue

Hadrian Wall, UK © Dr. Jean-Paul Rodrigue

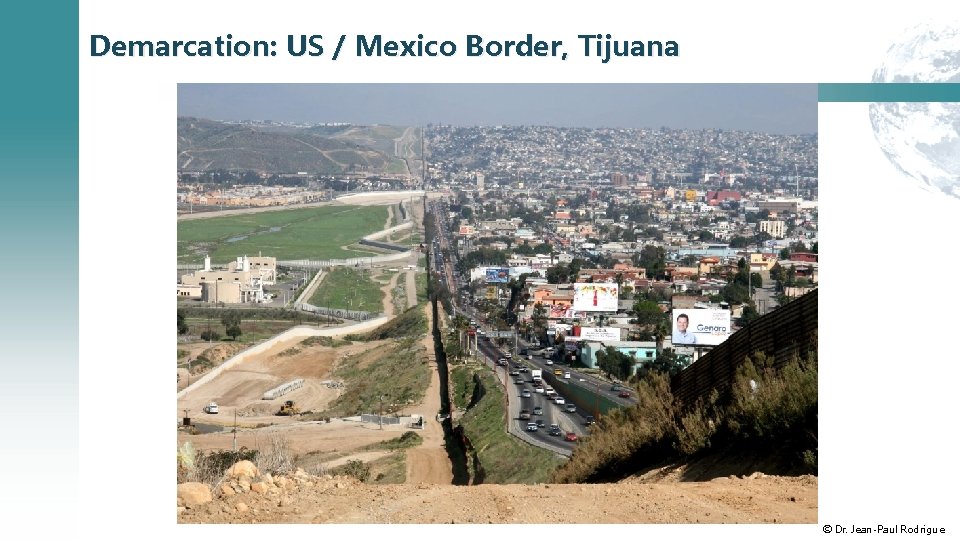

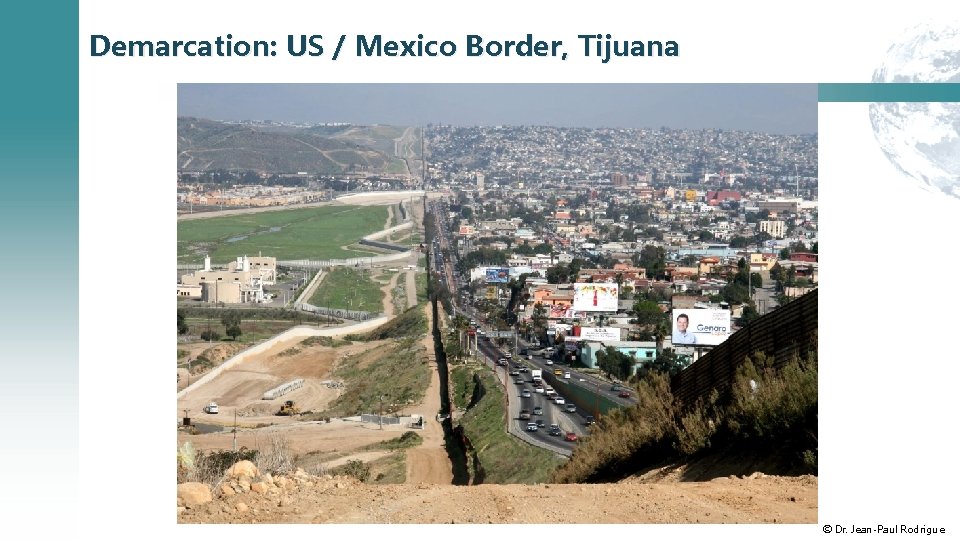

Demarcation: US / Mexico Border, Tijuana © Dr. Jean-Paul Rodrigue

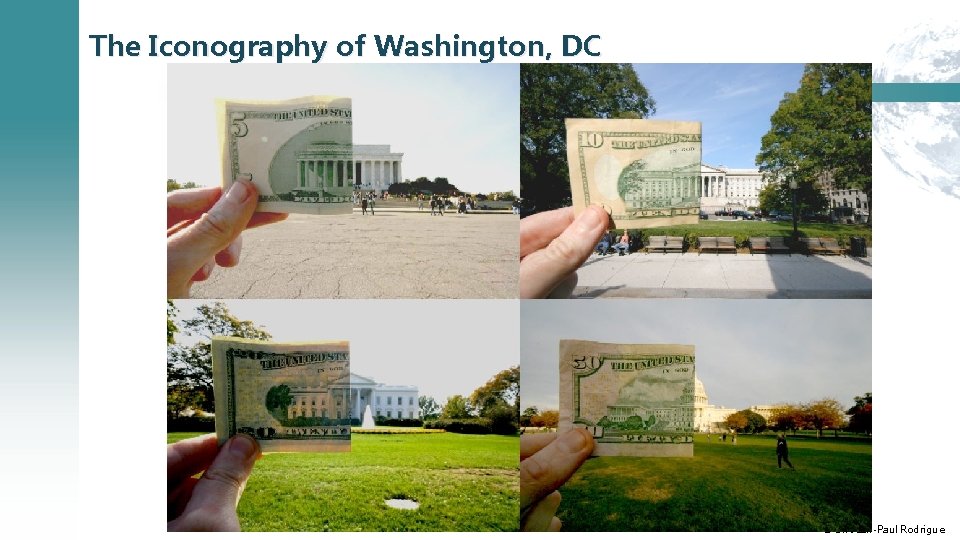

National Iconography in the Landscape ■ Iconography • Cultural landscape is rich in symbolism and visual metaphor, and political messages are often conveyed through such means. • Statues of national heroes or heroines and of symbolic figures. • Political iconography of landscape derives from an elite, dominant group in a country’s population. • Purpose is to legitimize or justify power and control over an area. • Capitals are shaping national identity. © Dr. Jean-Paul Rodrigue

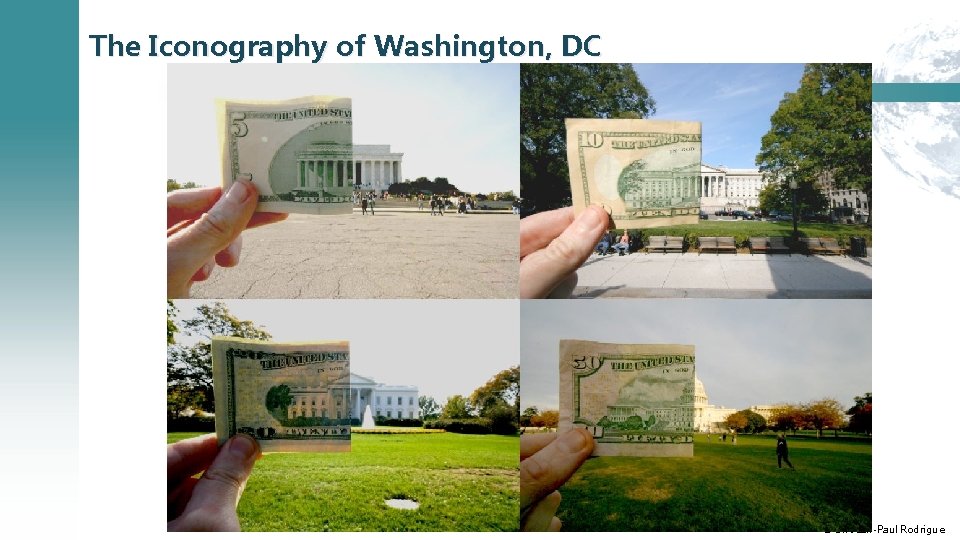

The Iconography of Washington, DC © Dr. Jean-Paul Rodrigue