Geo 479579 Geostatistics Ch 16 Modeling the Sample

- Slides: 47

Geo 479/579: Geostatistics Ch 16. Modeling the Sample Variogram

Necessity of Modeling Variograms § Sample variograms do not provide all of the separation distances (h) and the corresponding semivariances needed by the kriging system § It is necessary to have a model that enables computing a variogram value for any possible separation distance

Outline of the Chapter § Constraints that must be satisfied by a variogram model § Several basic variogram models § Combining basic models to build a general model of the sample variogram in one direction § Modeling a geometric and zonal anisotropy in two or three dimensions with different combinations of the basic models § Consistency between axes of anisotropy and those of the data coordinate system

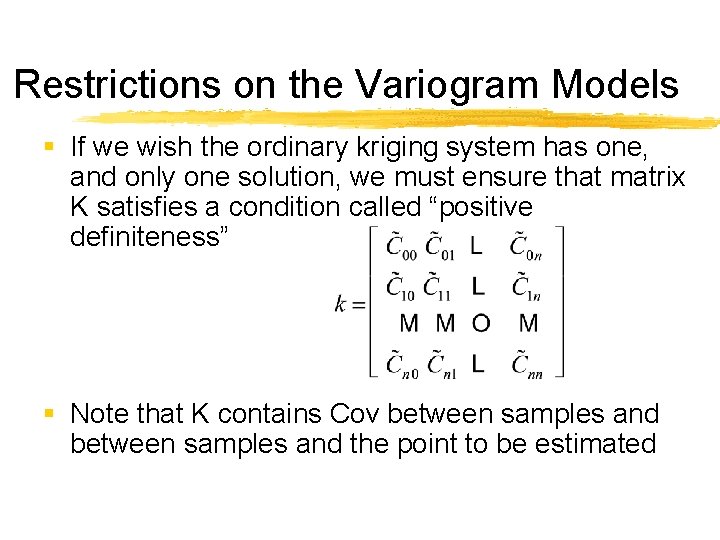

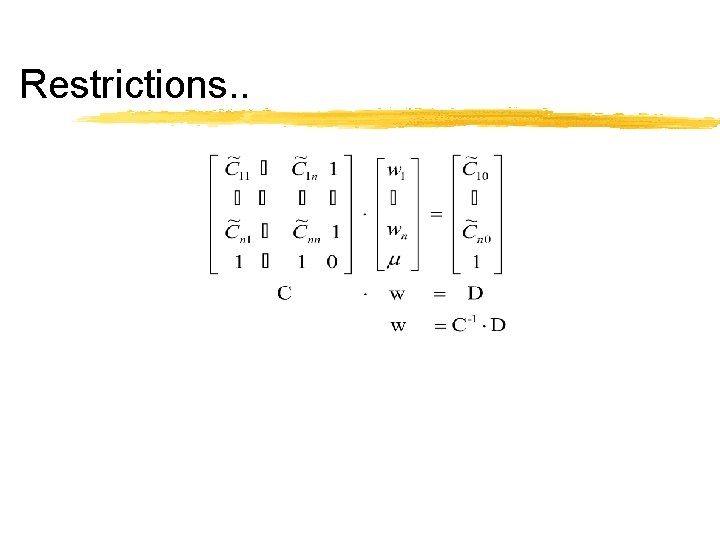

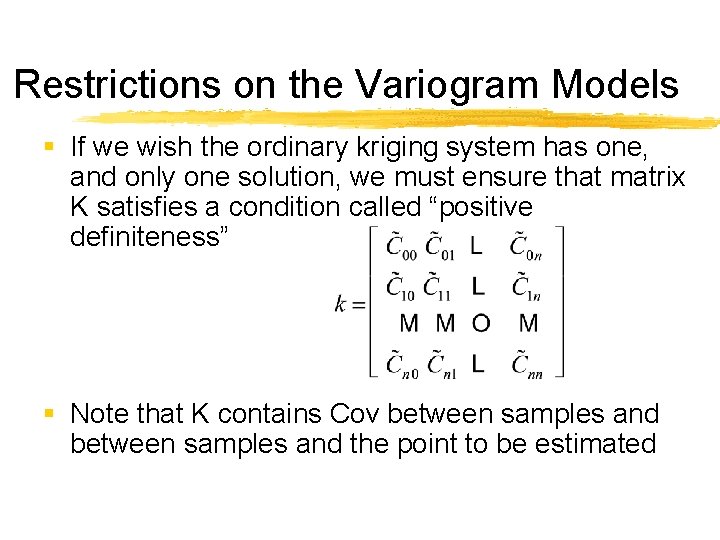

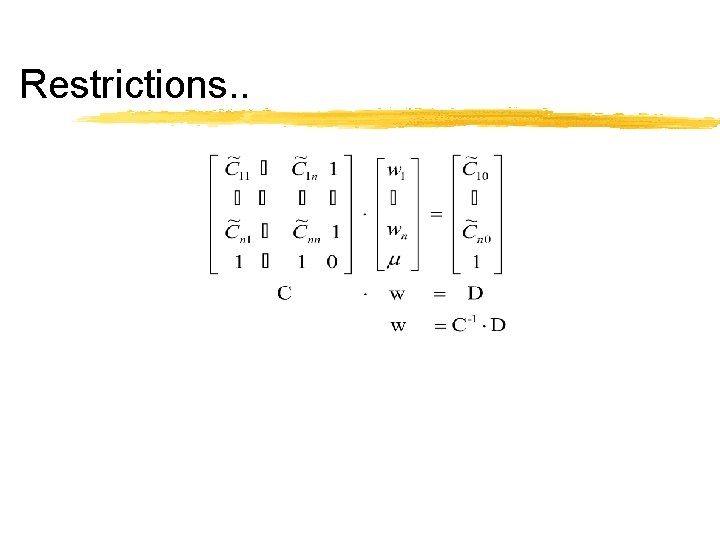

Restrictions on the Variogram Models § If we wish the ordinary kriging system has one, and only one solution, we must ensure that matrix K satisfies a condition called “positive definiteness” § Note that K contains Cov between samples and the point to be estimated

Restrictions. .

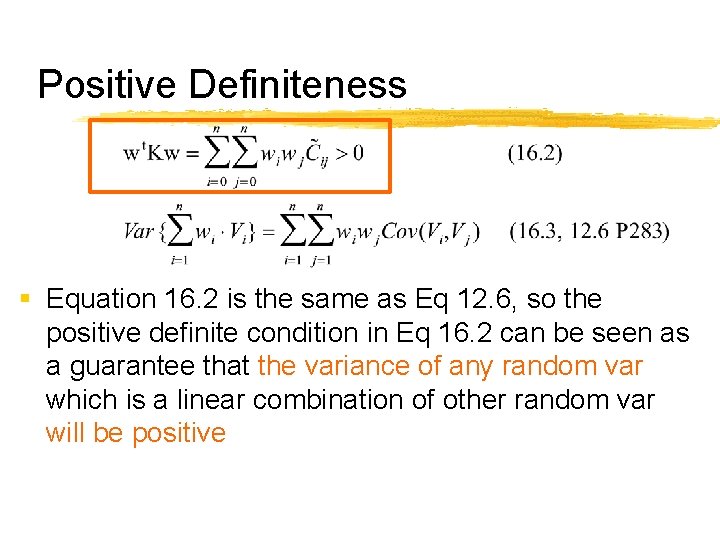

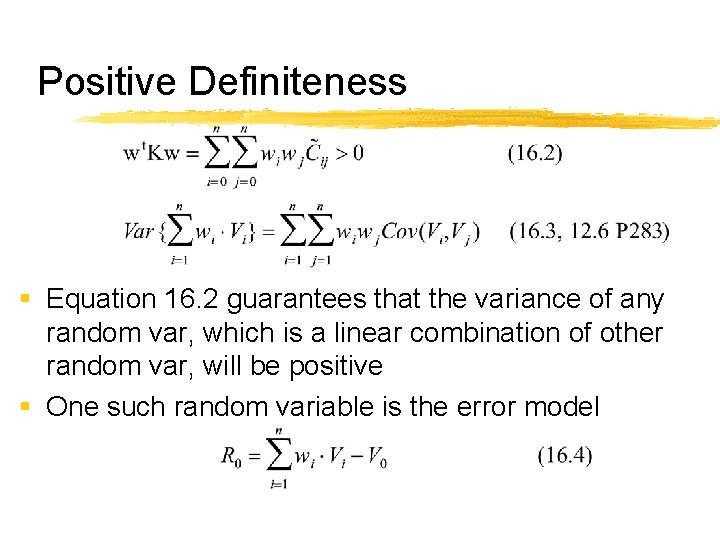

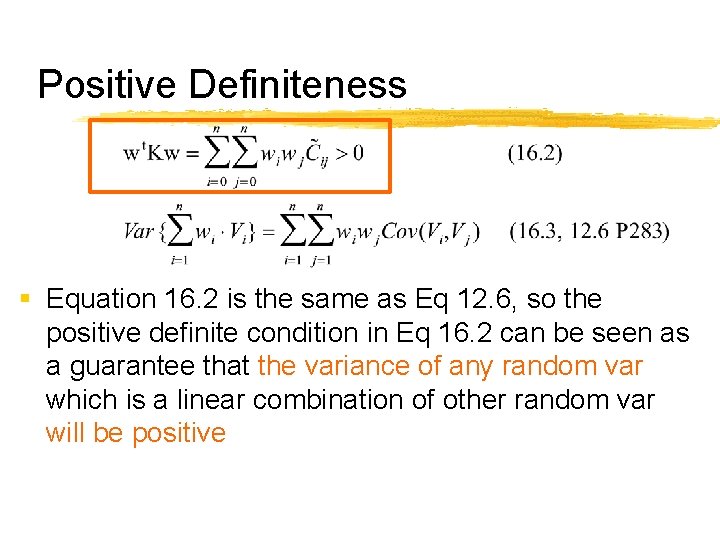

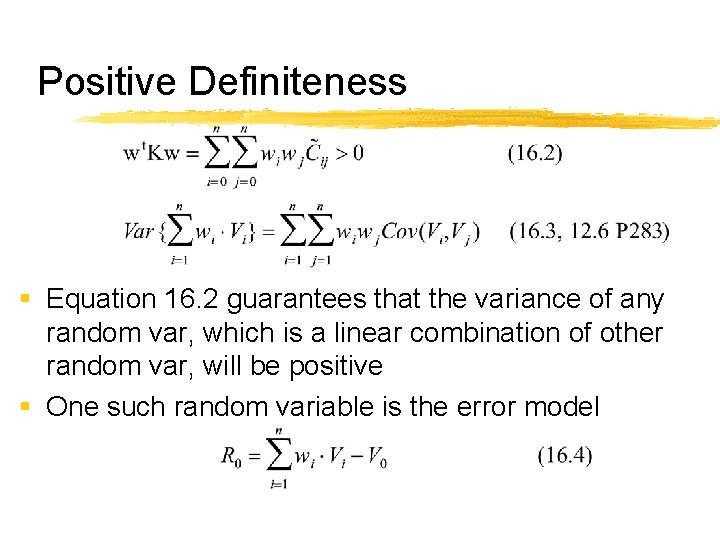

Positive Definiteness § Equation 16. 2 is the same as Eq 12. 6, so the positive definite condition in Eq 16. 2 can be seen as a guarantee that the variance of any random var which is a linear combination of other random var will be positive

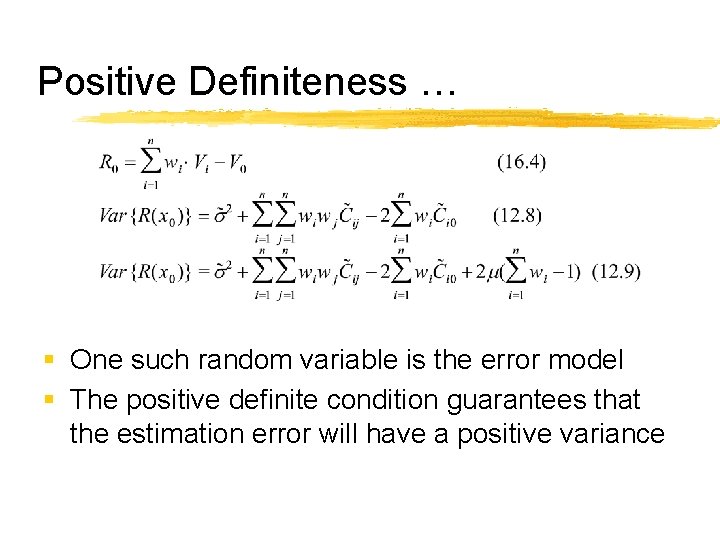

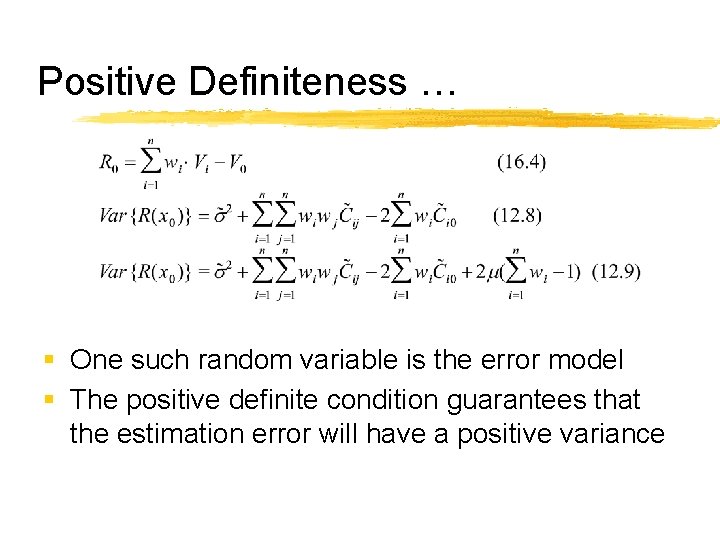

Positive Definiteness … § One such random variable is the error model § The positive definite condition guarantees that the estimation error will have a positive variance

Positive Definite Variogram Models § We can use a few functions that are known to satisfy the positive definite condition § Any linear combination of positive definite variogram models are also positive definite models § Basic models presented in this section are positive definite and simple

Positive Definite Variogram Models. . § Variogram models can be divided into two types, those that reach a plateau and those that do not § Transition models are those that reach a plateau. The plateau is the sill, and the corresponding lag distance is the range. § Some of the transition models reach their sill asymptotically. Their range is arbitrarily defined to be the lag distance at which 95% of the sill is reached § In this section, all sills are standardized to 1

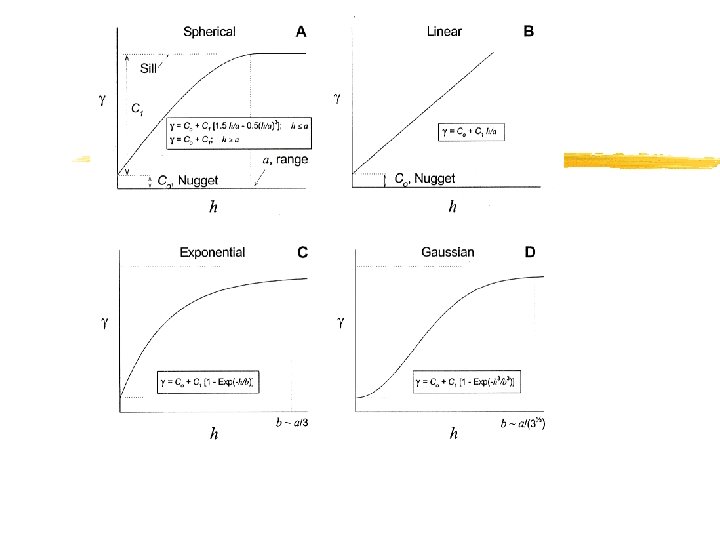

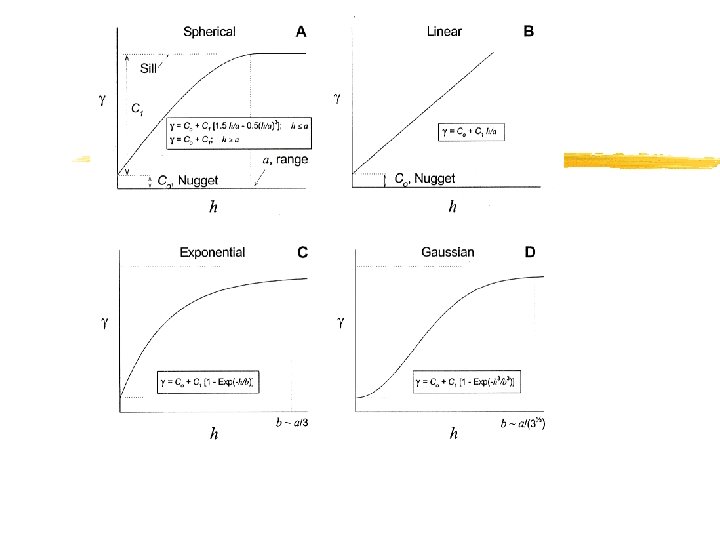

Variogram Models. . § 1. Nugget Effect Model (C 0) § 2. Spherical Model It has a linear behavior at small h near 0 but flattens out at larger h, and reaches the sill at a

Variogram Models. . § 3. The Exponential Model It is linear at small h near 0, but it rises more steeply and then flattens out more gradually than the spherical model It reaches its sill asymptotically. Its practical range, a, corresponds to 95% of the sill

Basic Variogram Models. . § 4. The Gaussian Model It is used to model extremely continuous phenomena It reaches its sill asymptotically. Its practical range corresponds to 95% of the sill § 5. The Linear Model

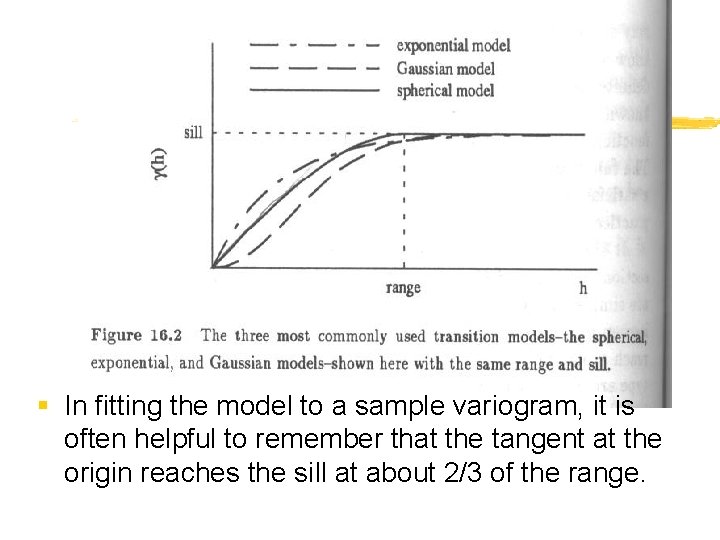

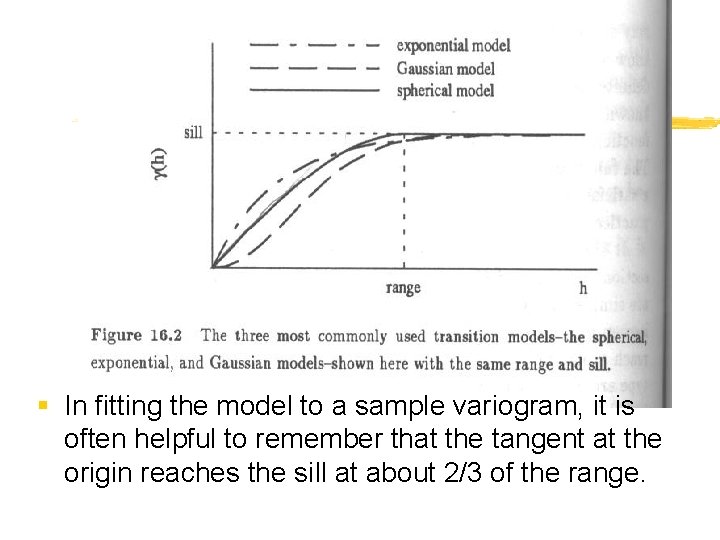

§ In fitting the model to a sample variogram, it is often helpful to remember that the tangent at the origin reaches the sill at about 2/3 of the range.

Models in One Direction § The choice of basic models usually depends on the behavior of the sample variogram near the origin: - Parabolic behavior Gaussian - Linear behavior Spherical or Exponential

Models in One Direction. . § Combination of models: nested structures § E. g. for a sample variogam that does not reach a stable sill but has a parabolic behavior near the origin, we may combine a Gaussian and a linear model

Models in One Direction. . § Principle of parsimony: complex models are not necessarily better than simple models § The physical explanation of the phenomenon is important § Of the parameters, a and C 0 are easy to decide. Picking the weight for each model often requires a “trial and error” approach, and all weights must sum to the sill

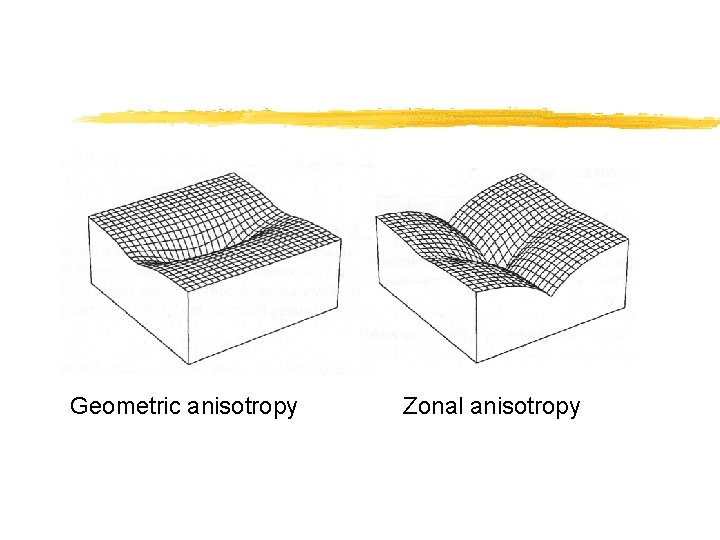

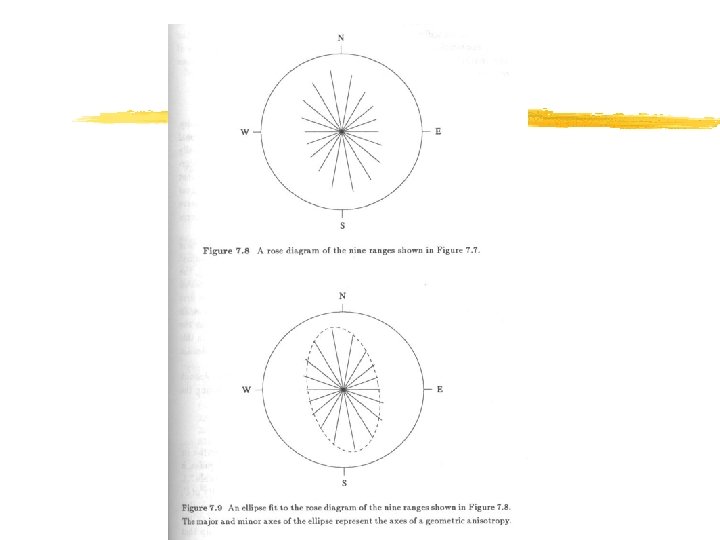

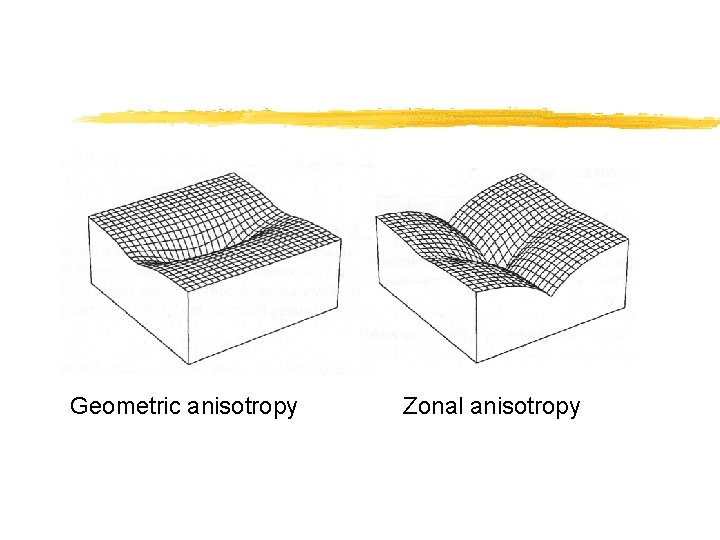

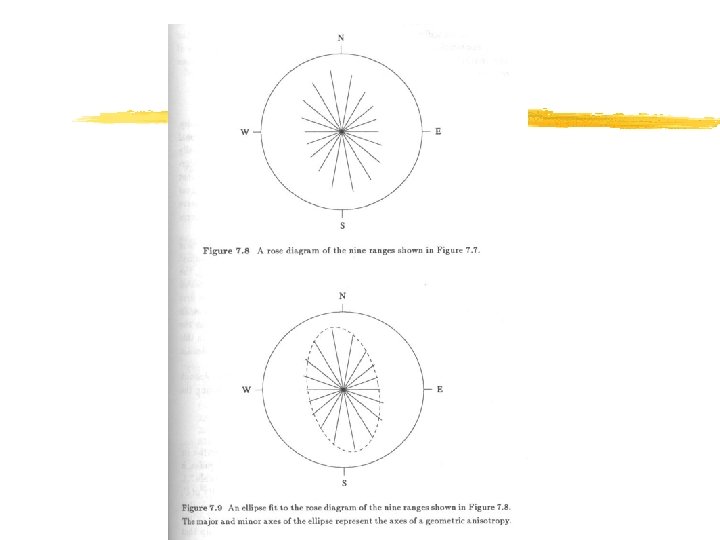

Models of Anisotropy § Geometric anisotropy: range changes with direction while sill remains constant (Fig 16. 3 a, p 378) § Zonal anisotropy: sill changes with direction while range remains constant (Fig 16. 3 b) § To deal with changes of range and sill with direction, we need to identify the anisotropy axes, using variogram surface maps or knowledge of the phenomenon

Geometric anisotropy Zonal anisotropy

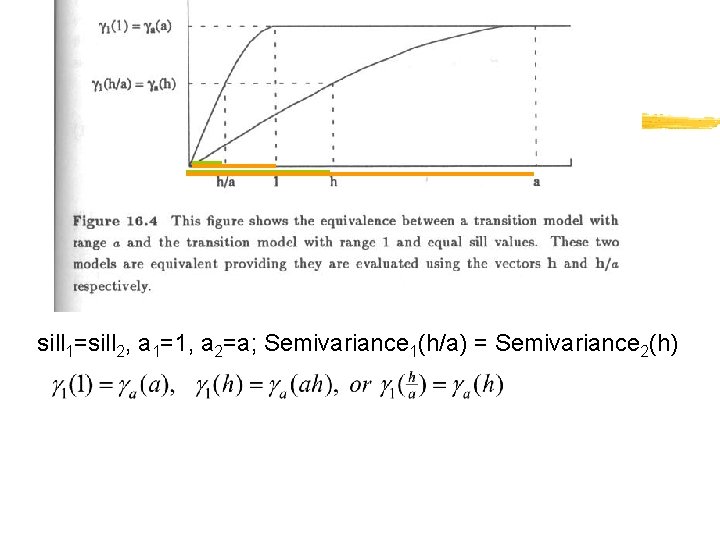

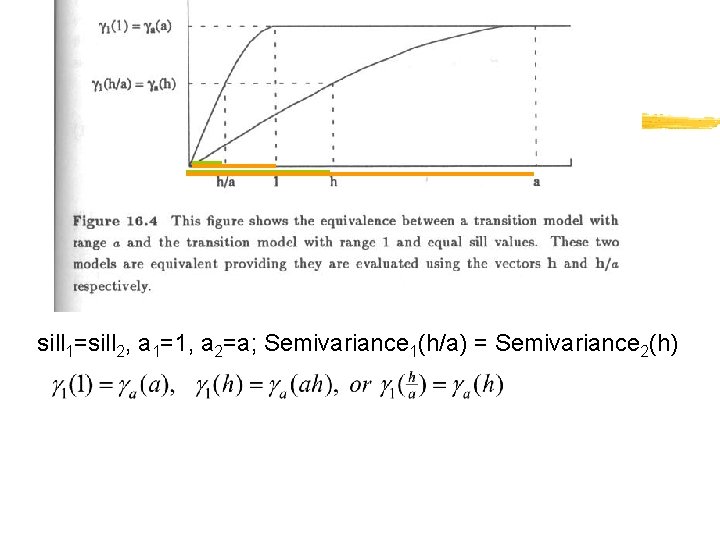

Models of Anisotropy. . § We need to combine directional variogram models into a single model that is consistent in all directions. To do this, we need to define a transformation that reduces all directional variograms to a common model with a standardized range of 1 § The trick is to transform the separation distance so that the standardized model will provide a variogram value that is identical to any of the directional models for that separation distance

sill 1=sill 2, a 1=1, a 2=a; Semivariance 1(h/a) = Semivariance 2(h)

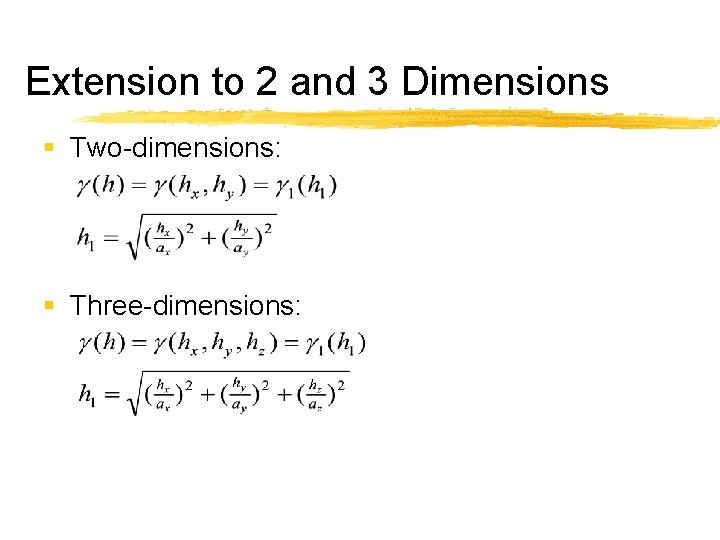

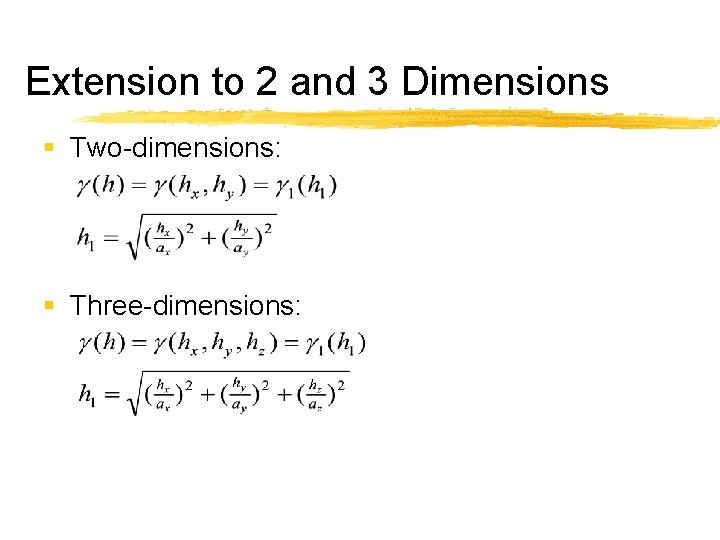

Extension to 2 and 3 Dimensions § Two-dimensions: § Three-dimensions:

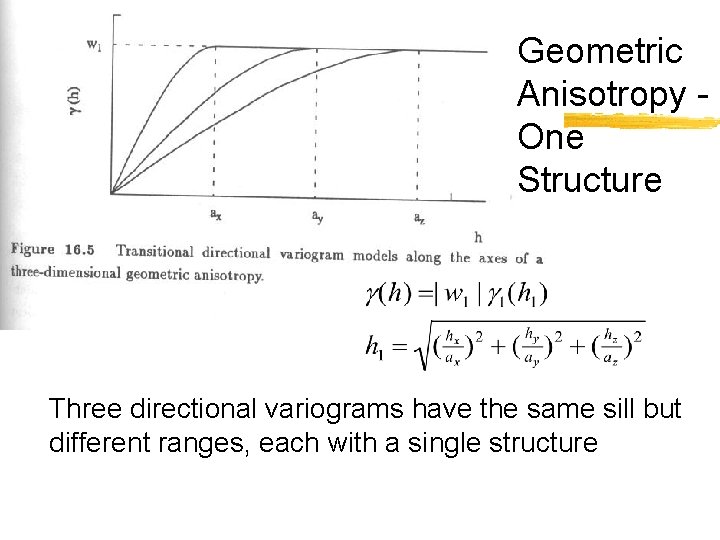

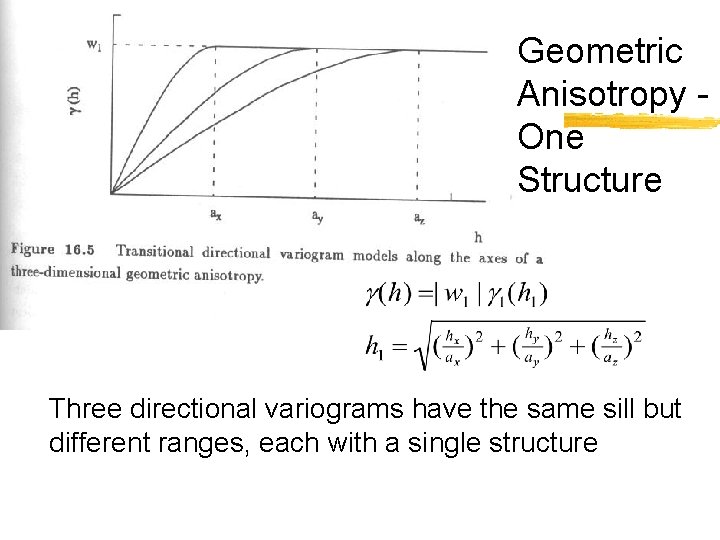

Geometric Anisotropy One Structure Three directional variograms have the same sill but different ranges, each with a single structure

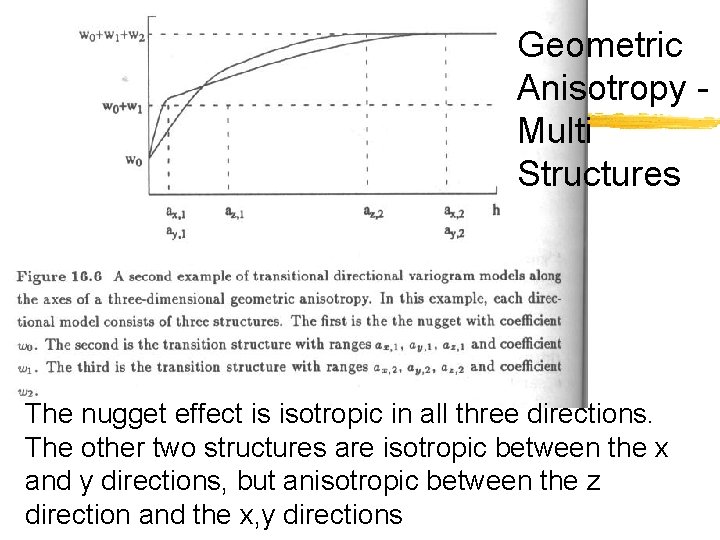

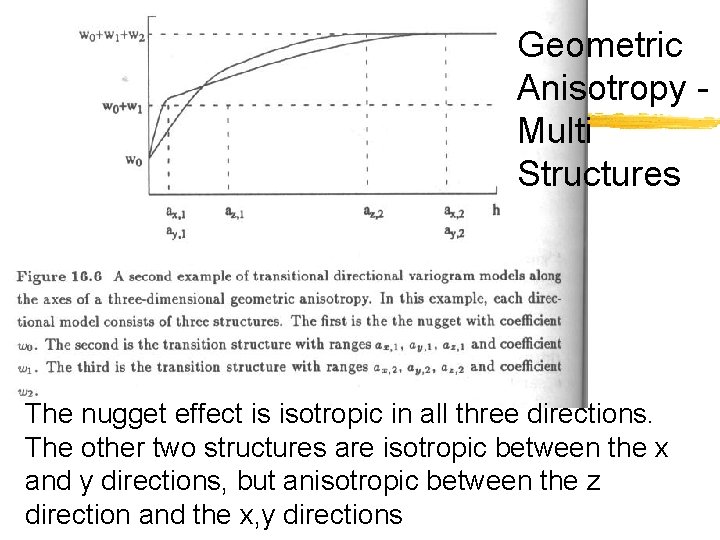

Geometric Anisotropy Multi Structures The nugget effect is isotropic in all three directions. The other two structures are isotropic between the x and y directions, but anisotropic between the z direction and the x, y directions

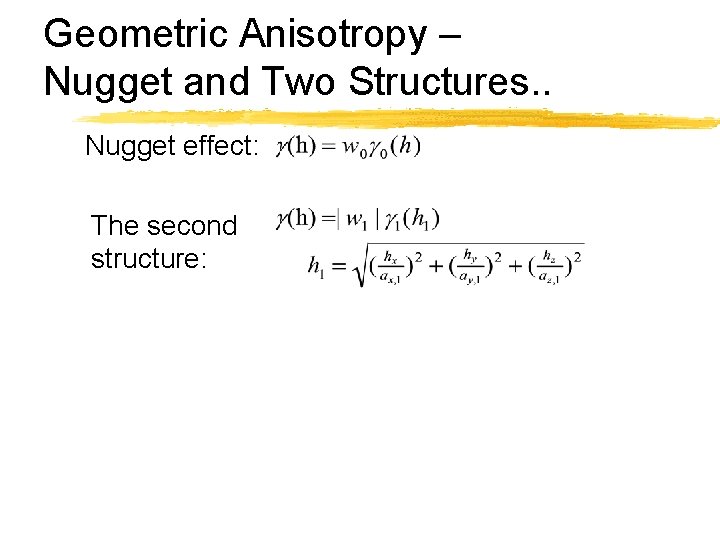

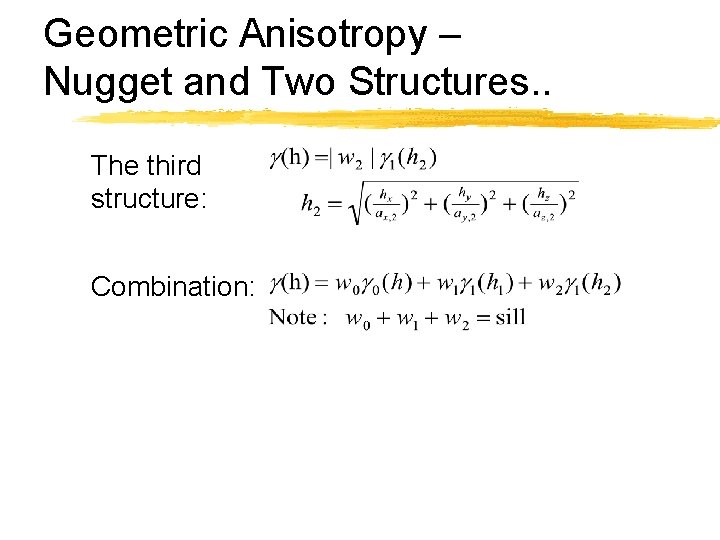

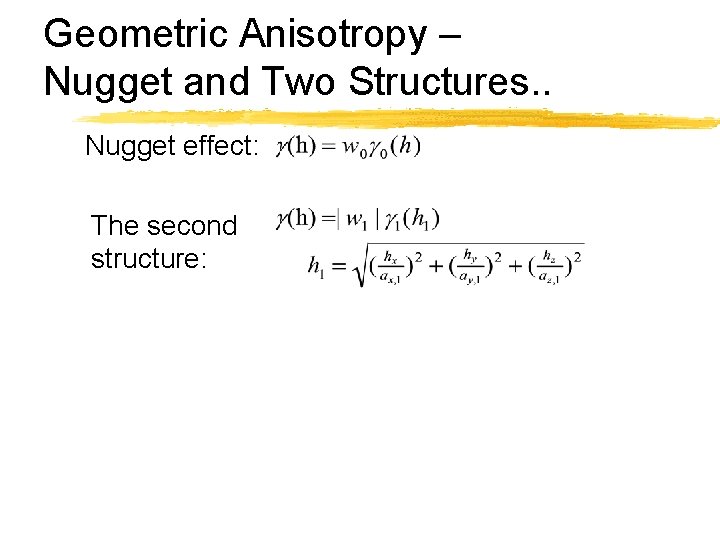

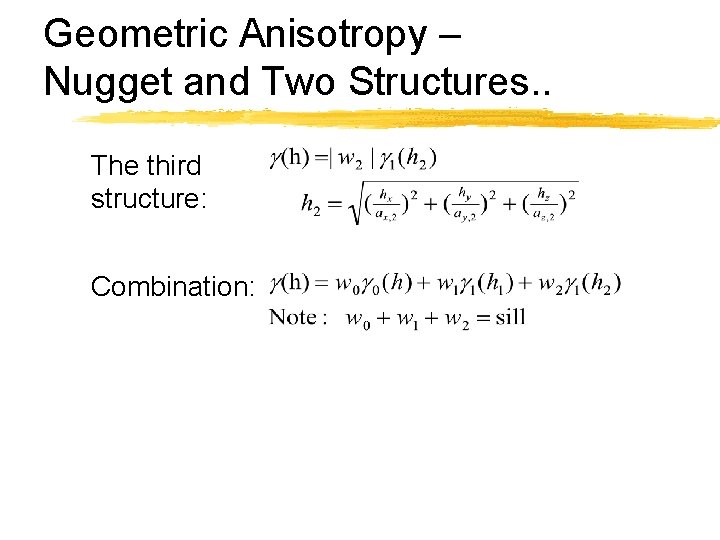

Geometric Anisotropy – Nugget and Two Structures. . Nugget effect: The second structure:

Geometric Anisotropy – Nugget and Two Structures. . The third structure: Combination:

Geometric Anisotropy Summary § For each nested structure, the directional models must all be the same type, i. e. all spherical, or all exponential, or etc. § All directional models must have identical sill and wi § The model types can differ between nested structures, e. g. the first is Gaussion, while the second can be spherical

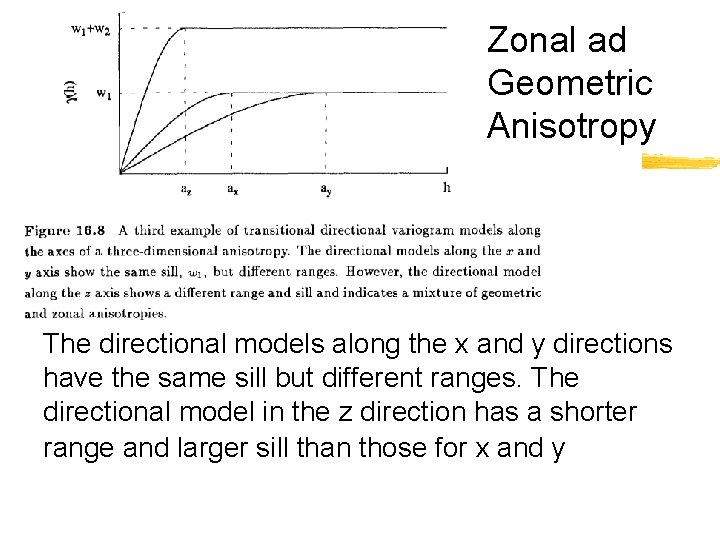

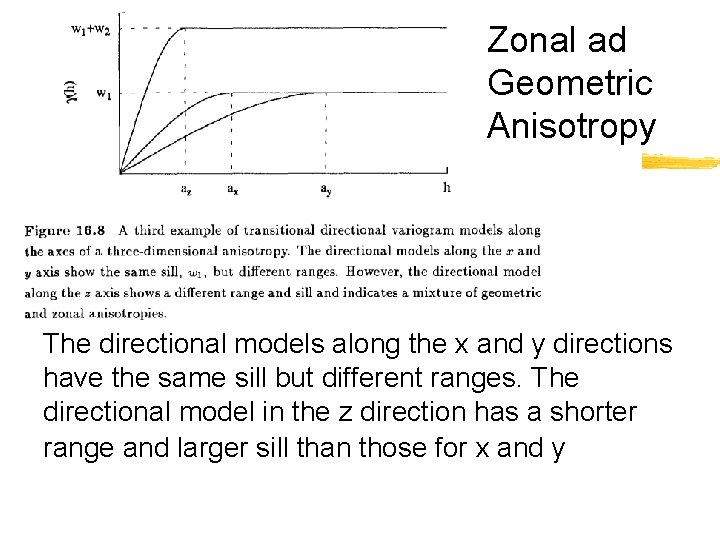

Zonal ad Geometric Anisotropy The directional models along the x and y directions have the same sill but different ranges. The directional model in the z direction has a shorter range and larger sill than those for x and y

Zonal and Geometric Anisotropy. . § First structure: Geometric anisotropy An isotropic model along x and y directions with a sill of and a range of 1 § Second structure: Zonal anisotropy with a sill of and exists only in the hz direction § The complete model:

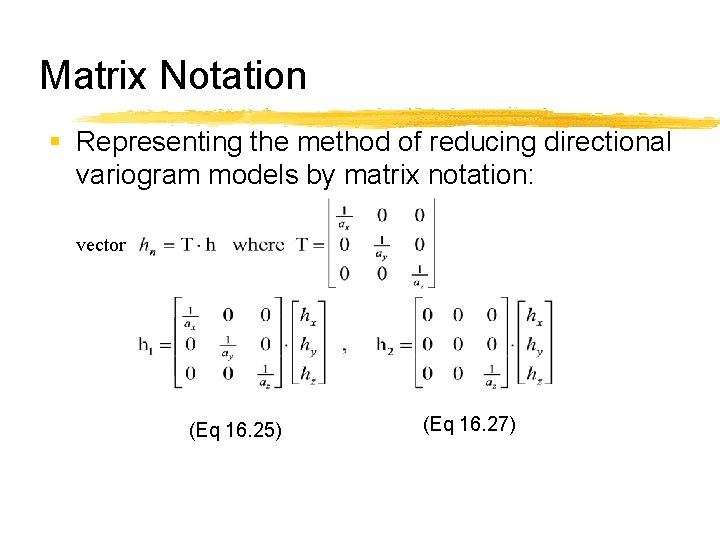

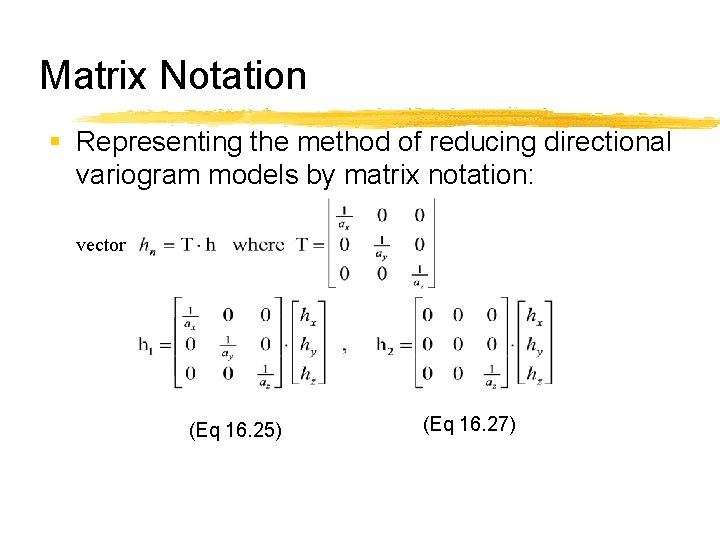

Matrix Notation § Representing the method of reducing directional variogram models by matrix notation: vector (Eq 16. 25) (Eq 16. 27)

Matrix Notation … § Check the final model. E. g. It should return w 1 at range ax in direction x § Eq 16. 25, 16. 27

Coordinate Transformation by Rotation § Anisotropy axes often do not coincide with the axes of the data coordinate system, i. e. x, y, z directions § The orientation of of the anisotropy is controlled by some feature in the data, while the orientation of the coornate system is arbitrary

Coordinate Transformation by Rotation § In this case, the components (hx, hy, hz) of the separation vector h in the data coordinate system will have different values when referenced in the coordinate system coincident with the anisotropy axes § Thus, it is necessary to transform the vector from the data coordinate system to the coordinate system coincident with the anisotropy axes before evaluating the variogram model

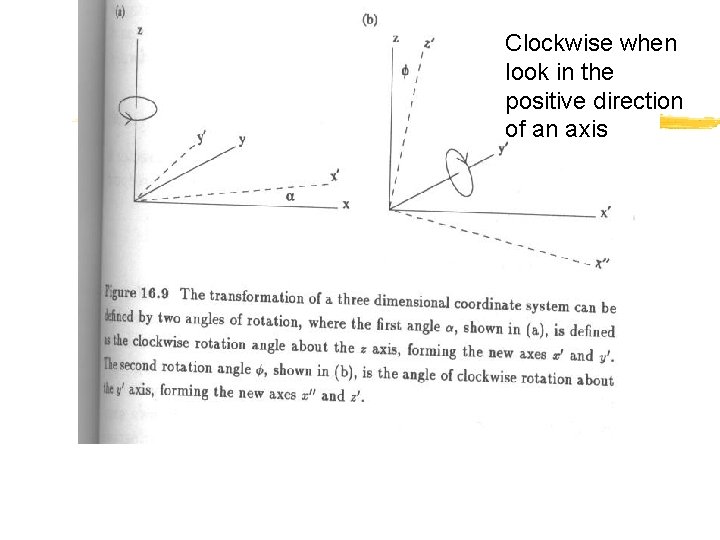

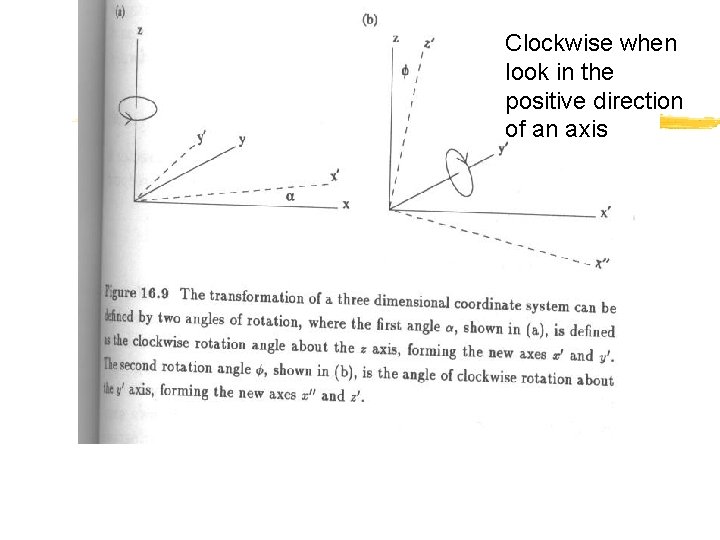

Clockwise when look in the positive direction of an axis

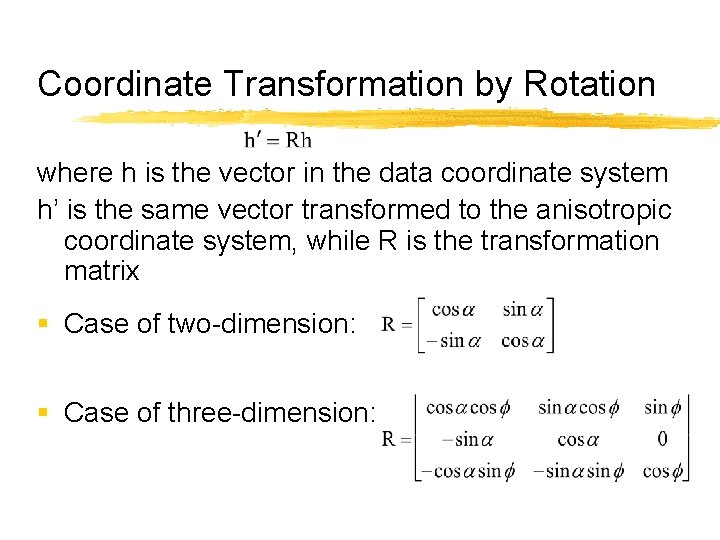

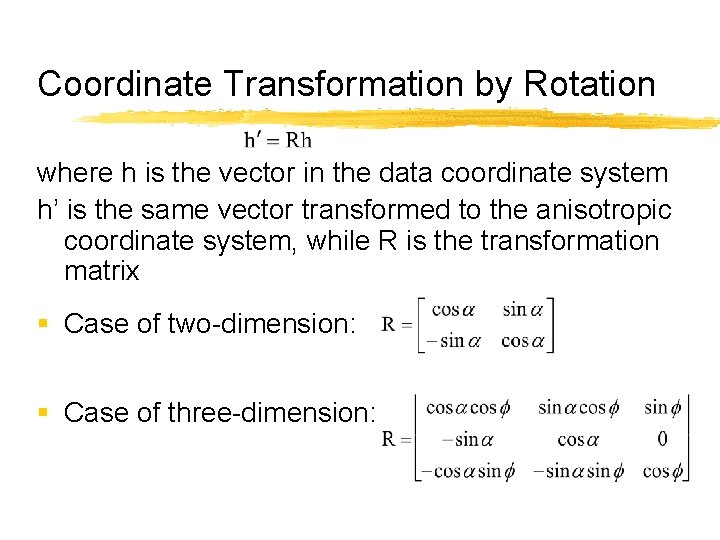

Coordinate Transformation by Rotation where h is the vector in the data coordinate system h’ is the same vector transformed to the anisotropic coordinate system, while R is the transformation matrix § Case of two-dimension: § Case of three-dimension:

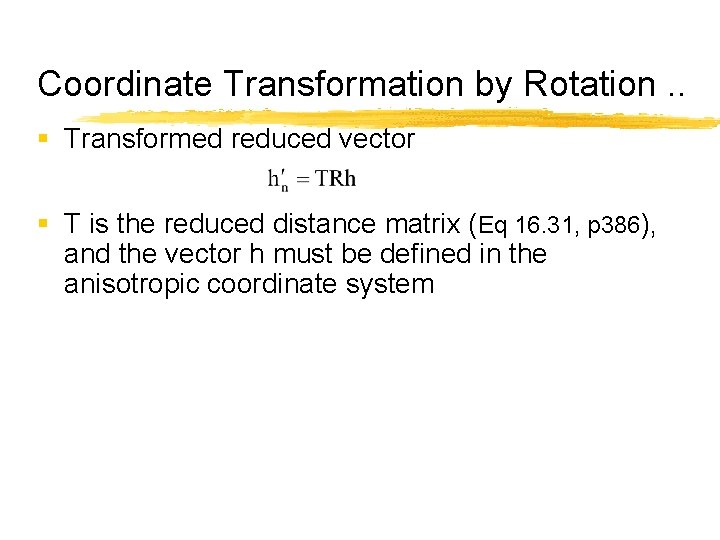

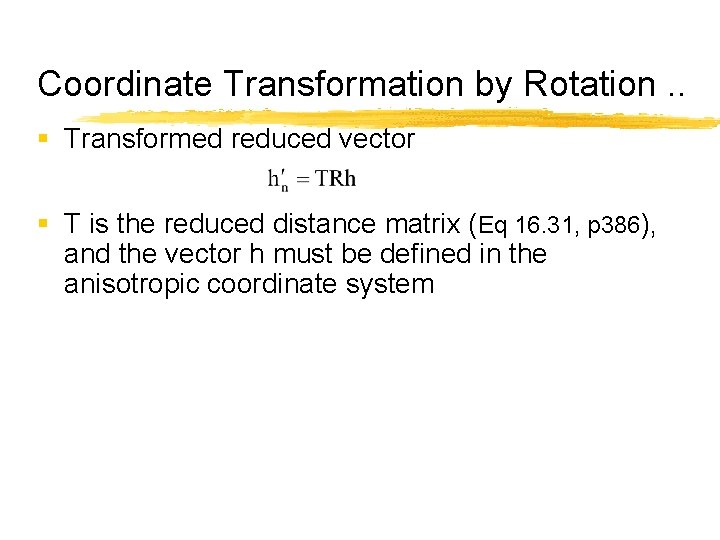

Coordinate Transformation by Rotation. . § Transformed reduced vector § T is the reduced distance matrix (Eq 16. 31, p 386), and the vector h must be defined in the anisotropic coordinate system

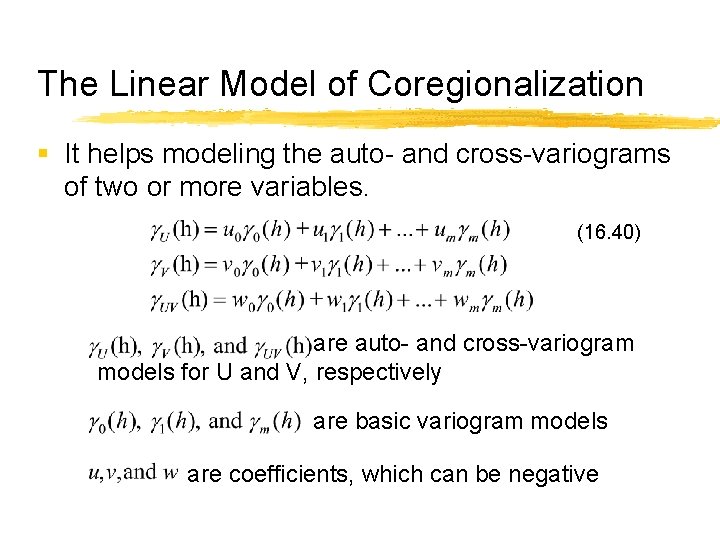

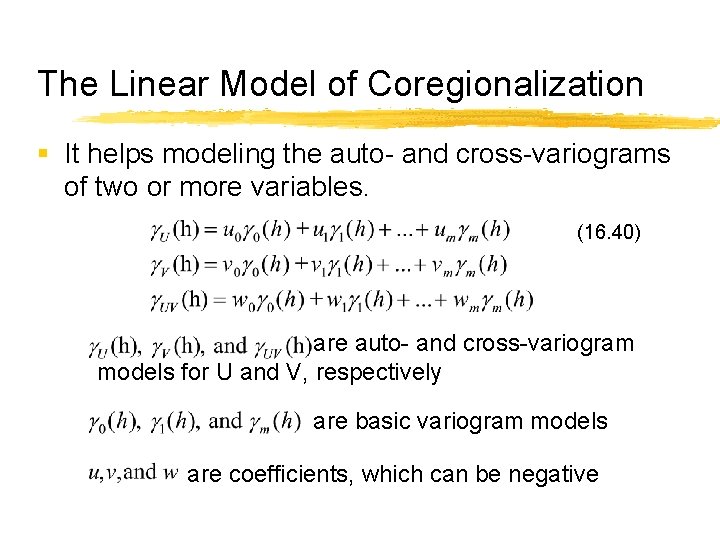

The Linear Model of Coregionalization § It helps modeling the auto- and cross-variograms of two or more variables. (16. 40) are auto- and cross-variogram models for U and V, respectively are basic variogram models are coefficients, which can be negative

The Linear Model of Coregionalization. . § The auto- and cross-variograms can be rewritten in a matrix form as combinations of each basic model § Combinations of the first basic model, § § 11 = row 1* col 1 12 = row 1* col 2 21 = row 2* col 1 22 = row 2* col 2

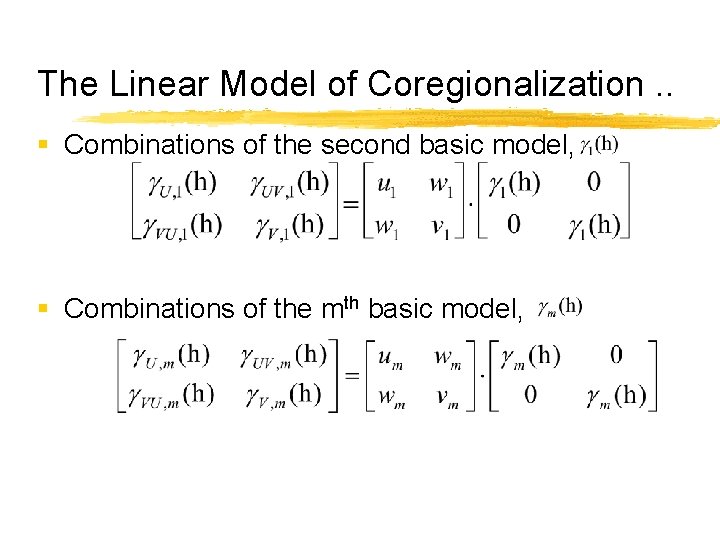

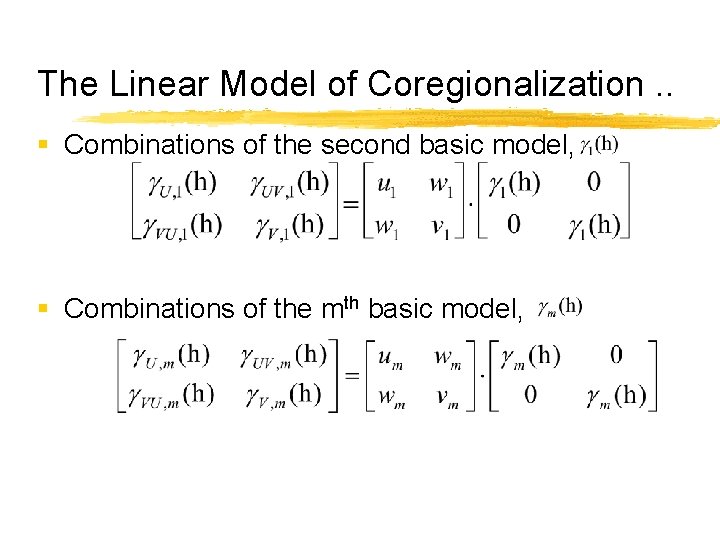

The Linear Model of Coregionalization. . § Combinations of the second basic model, § Combinations of the mth basic model,

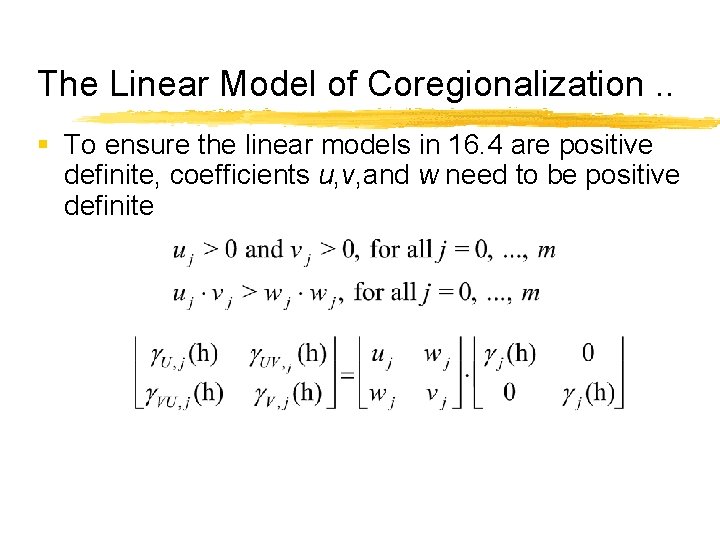

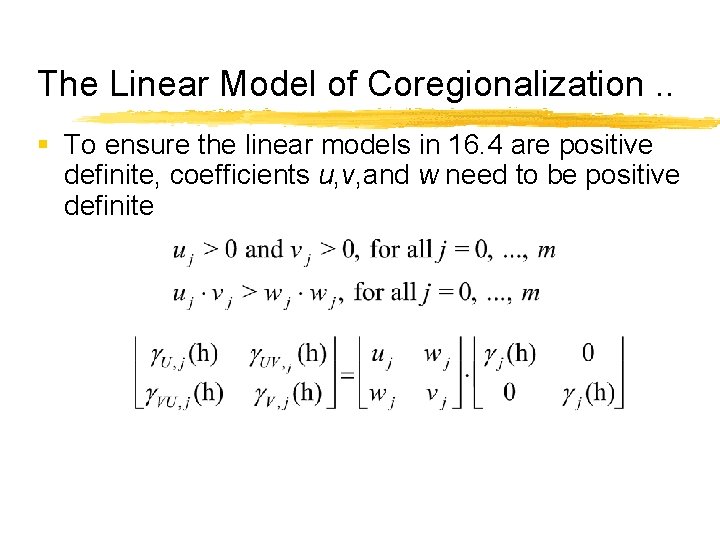

The Linear Model of Coregionalization. . § To ensure the linear models in 16. 4 are positive definite, coefficients u, v, and w need to be positive definite

Positive Definiteness § Equation 16. 2 guarantees that the variance of any random var, which is a linear combination of other random var, will be positive § One such random variable is the error model

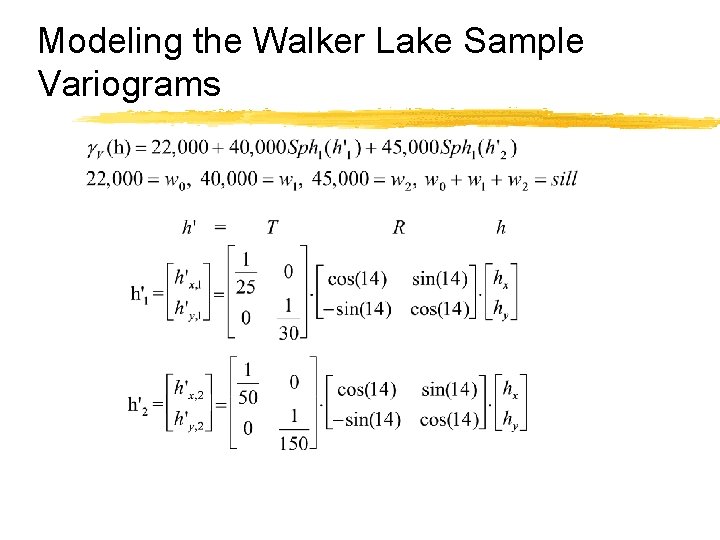

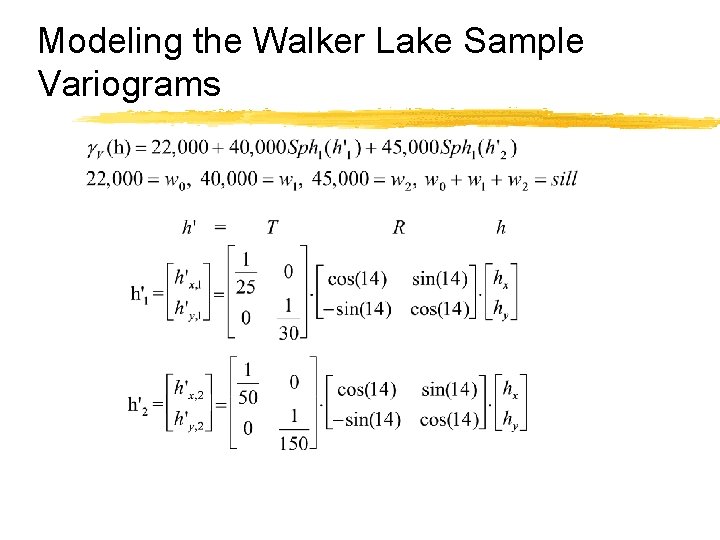

Modeling the Walker Lake Sample Variograms

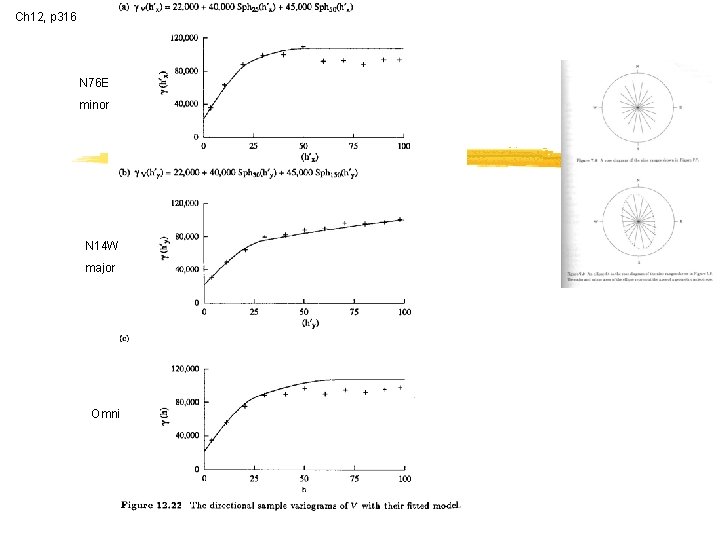

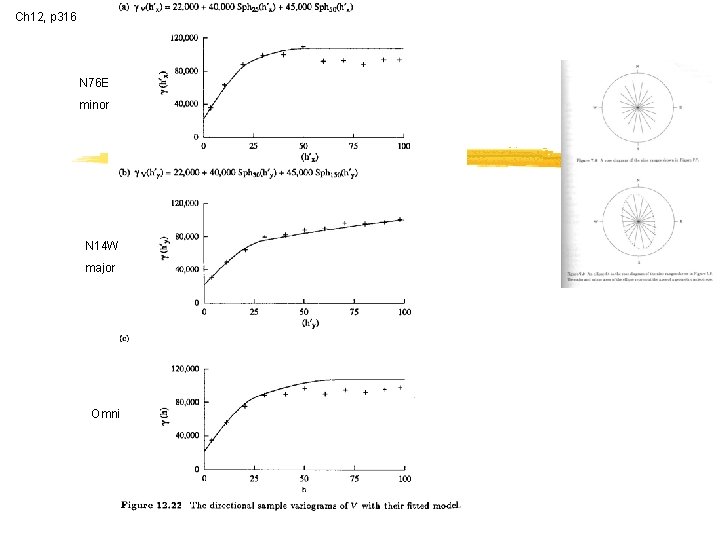

Ch 12, p 316 N 76 E minor N 14 W major Omni

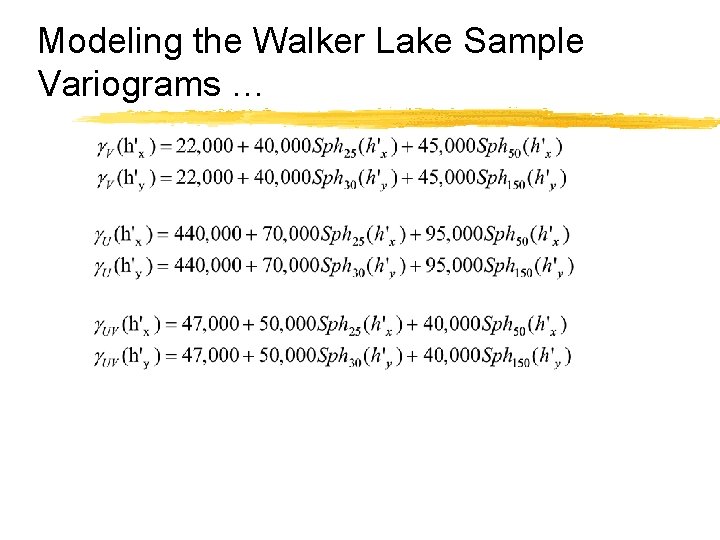

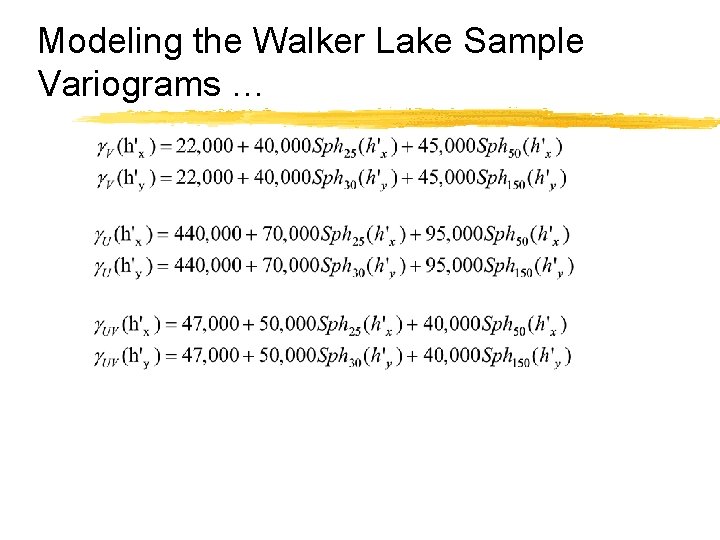

Modeling the Walker Lake Sample Variograms …

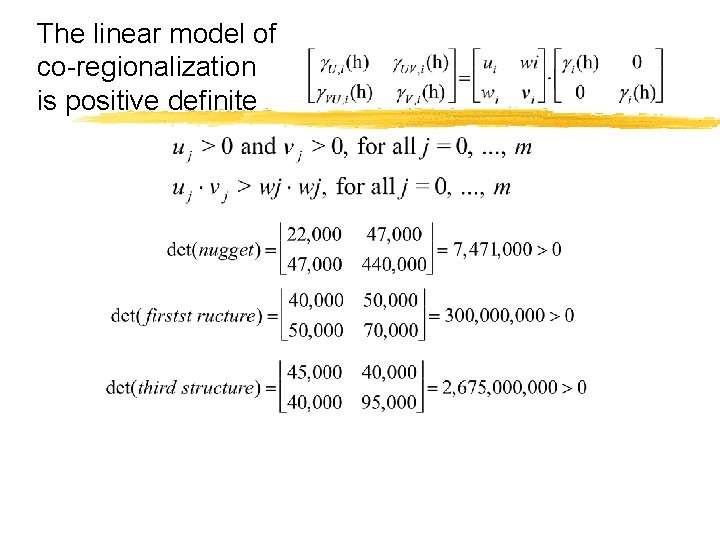

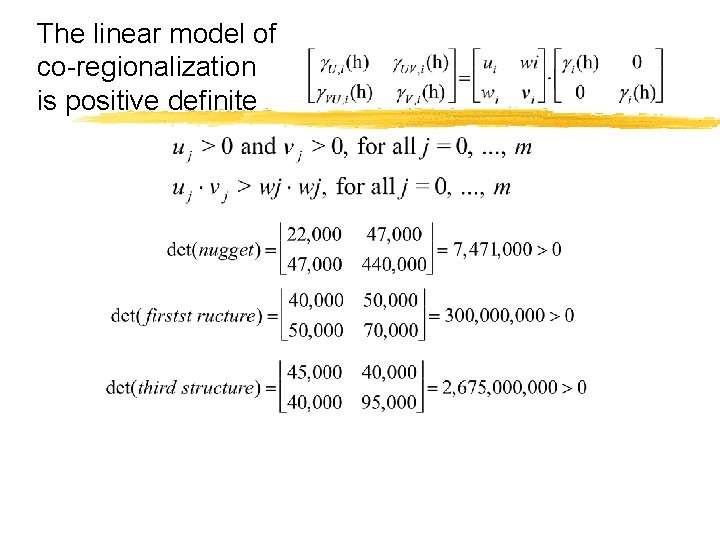

The linear model of co-regionalization is positive definite

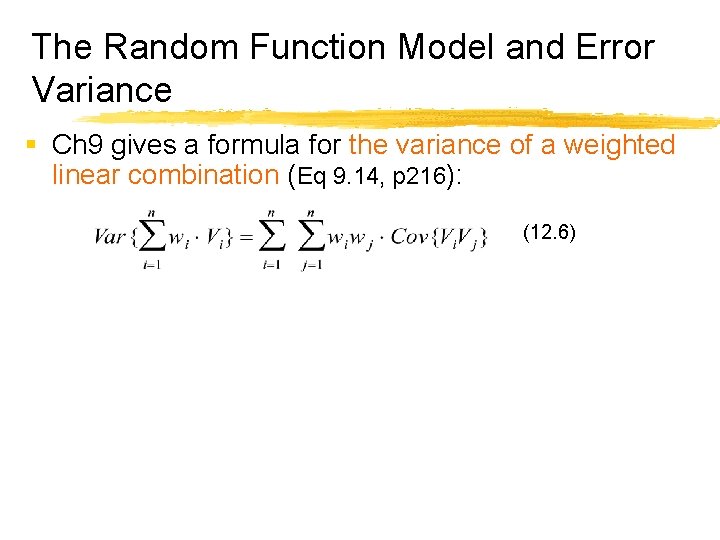

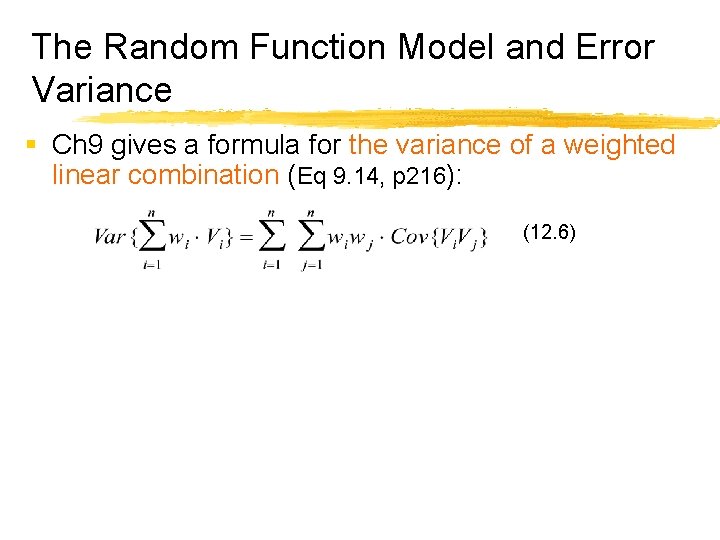

The Random Function Model and Error Variance § Ch 9 gives a formula for the variance of a weighted linear combination (Eq 9. 14, p 216): (12. 6)