Genetic and shared environmental influences on brain development

Genetic and shared environmental influences on brain development from birth to age 2 -years Timothy C. Bates University of Edinburgh Mike Neale Virginia Institute of Psychiatric Genetics John Gilmore University of North Carolina

Foetal brain… Illustration by Helen Spiers

Brain development and growth • Single most important biological marker for cognition – (Mc. Daniel, 2005) • Linked to psychiatric outcomes including schizophrenia – (Steen, Mull, Mcclure, Hamer, & Lieberman, 2006)

Lifetime consequence, early growth • Much of this critical growth occurs in the earliest years of life – Cortical gray matter more than doubles in the first year • (Gilmore et al. , 2012). • Influences known from adult studies – Parental social and economic status (SES) • (Hackman & Farah, 2009).

Logarithmic link of cortical volume to SES (Noble et al. 2015)

Forbes magazine

However: Genes can effect biological volumes… Common ancestor ~100 generations ago (h 2 growth ~ 0. 3) ©Roslin Institute

However… – Brain volumes are a highly heritable endophenotype • Blokland, de Zubicaray, Mc. Mahon, & Wright, 2012 – Morphology & psychological function genetic correlated • Posthuma et al. , 2002. – Specific genetic variants identified influencing structural volumes • Hibar et al. , 2015; Ikram et al. , 2012.

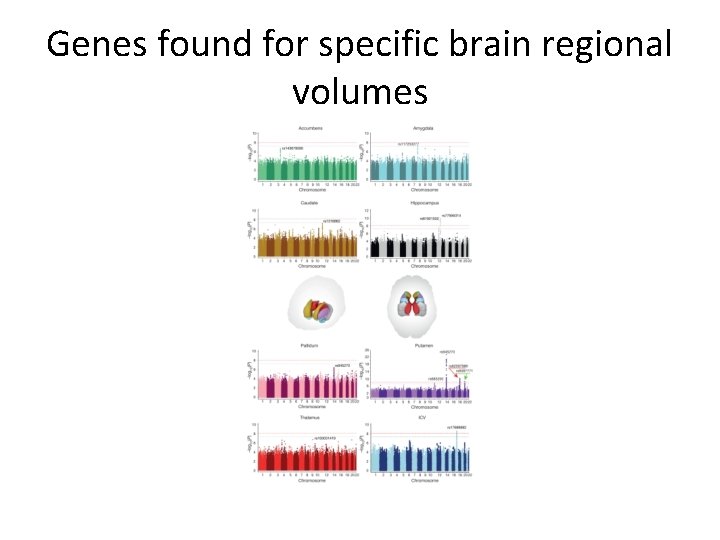

Genes found for specific brain regional volumes

Genetic or Environmental? • No studies have combined genetic and neurological examination in infancy

Prior data • Knowledge largely from studies of adults and children • Nature and number of influences during earliest years of infant brain development virtually unknown (Gilmore et al. , 2012) • Potential interaction effects with SES in the expression of genetic potential untested

Unique infant twin sample • Assessed longitudinally from shortly after birth through age-2 in three consecutive waves of brain imaging – Characterized on family environment. • 285 infants – 174 DZ (87 pairs) – 106 MZ (53 pairs)

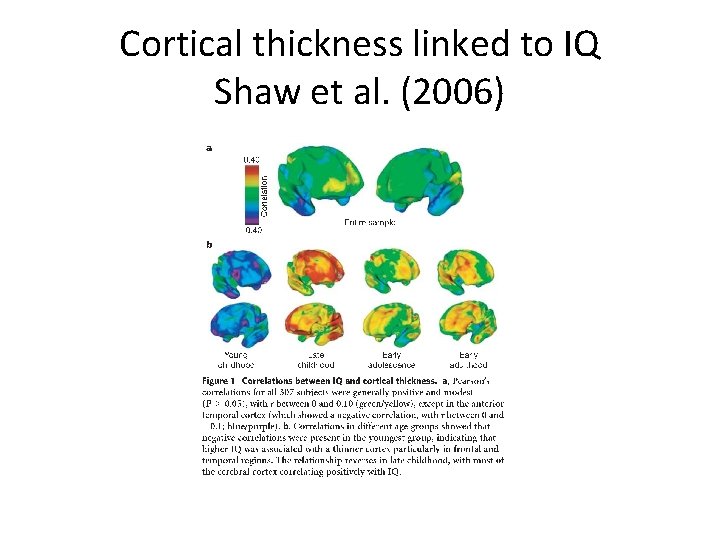

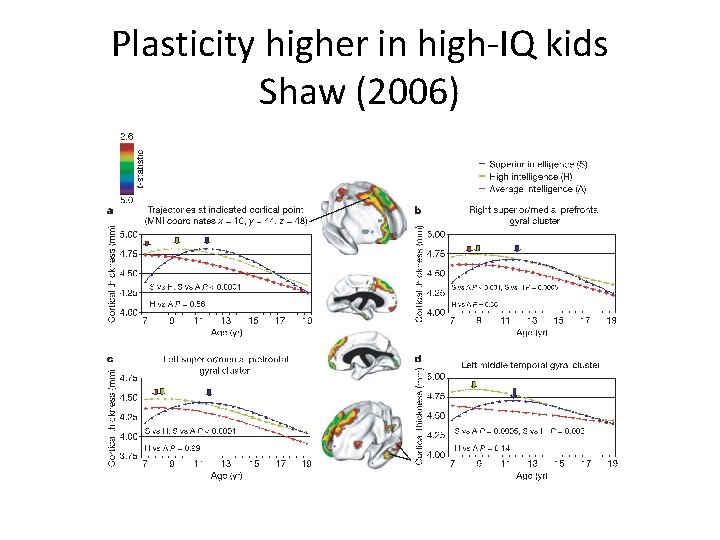

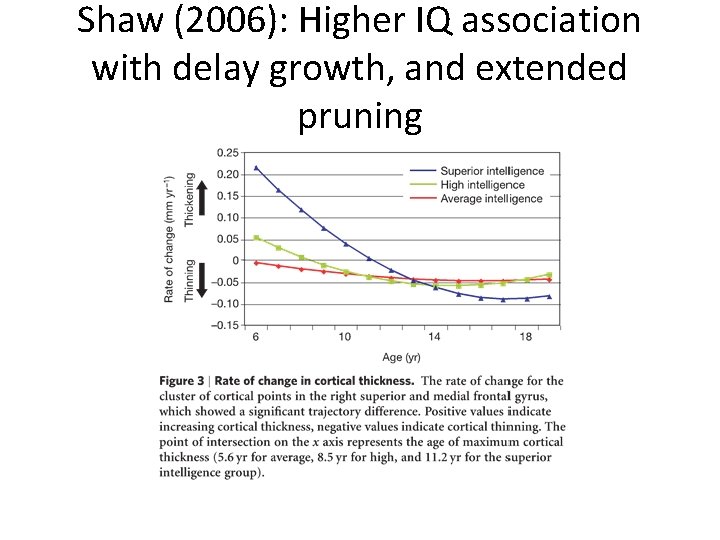

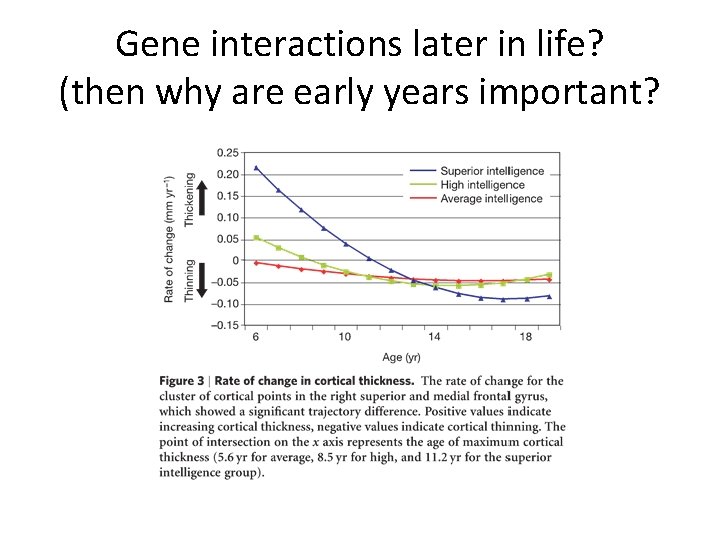

Landmark studies from 4 -20 years (Geed et al. , 1999) • Large increases in gray and white matter from ages 4 thru 20 -years • Gray matter volumes similarly increasing until a period of volume-reduction initiating at adolescence – Giedd et al. ( 1999) • These studies also showed the importance of temporal patterning per se – IQ is associated with cortical thickness in 6 to 11 year olds (Karama et al. , 2009) – but also – Complex and non-linear pattern of prolonged cortical thickening (Shaw et al. , 2006).

Cortical thickness linked to IQ Shaw et al. (2006)

Plasticity higher in high-IQ kids Shaw (2006)

Shaw (2006): Higher IQ association with delay growth, and extended pruning

Prior to age-4 • Much less is known about the nature and time course of brain development. • Heritabilities surprisingly high early in life. – Note: studies of IQ indicate much lower heritability in children compared to adults • (Haworth et al. , 2010)

Neonate heritabilities • Analyses of the neonatal wave of the present sample indicated heritability values only slightly lower than those found in child samples – h 2 of. 73 and. 85 for total intracranial and white matter volumes respectively – (Gilmore et al. , 2010). • Period from birth to age 2 is associated both with rapid increases in gray and white matter volumes and, in one study, with the emergence of gene × environment interaction – (Tucker-Drob, Rhemtulla, Harden, Turkheimer, & Fask, 2011) • Potential for complex interactions, and multiple genetic and environmental factors across time or operating at one, but not other developmental windows.

Present Study Initial Steps • Characterise Genetic and environmental factors influencing whole-brain volumetric development – Derived separately for gray and for white matter – Neonatal, and 1 - and 2 -years of age • Testing: – Continuities – discontinuities – modes of operation – including gene environment interactions.

Subjects • This paper reports on subjects taking part in the large, prospective study of early brain development – (Gilmore et al. , 2010). • Subjects were recruited prenatally and scanned shortly after birth, and at ages 1 and 2 years. – Also assessed with the Mullen Scales of Early Learning (Mullen, 1995) at ages 1 and 2 years. • Neonates were scanned at a median age of 35 days (range 9 and 161 days). Year 1 scans took place at a median age of 402 days (min 351, max 511), and year 2 follow-up scans at 770 days (min 661, max 879).

Method • MRI scans were performed on a Siemens 3 T head -only scanner (Allegra, Siemens Medical System, Erlangen, Germany). • The infants were not sedated, were fed before scanning, and given ear protection. • To reduce movement artifact, the head was aligned in using a weak vacuum-cup. • A nurse was present during all scans • Heart rate and oxygen saturation were monitored with a pulse oximeter.

Scans • T 1 -weighted structural pulse sequences were a 3 D magnetization prepared rapid gradient echo (MP- RAGE time repetition [TR] = 1820 ms, inversion time = 1100 ms, echo time = 4. 38 ms, flip angle = 7°, and n = 144). • Proton density and T 2 -weighted images were obtained with a turbo spin echo sequence (TR = 6200 ms, time echo [TE]1 = 20 ms, TE 2 = 119 ms, and flip angle 150°). • Spatial resolution was 1 × 1 -mm voxel for T 1 -weighted images, 1. 25 × 1. 5 -mm voxel with 0. 5 -mm inter-slice gap for proton density/T 2 weight images. • For children who failed or were deemed likely to fail due to difficulty sleeping, a ‘fast’’ sequence was done; 12 neonates had a ‘‘fast’’ T 2 scan with a decreased TR, image matrix and number of slices (5270 ms, 104 3 256 mm, 50) and 3 one year olds had a ‘‘fast’’ T 1 scan with a decreased image matrix (144 3 256 mm). • A clinical radiologist evaluated all scans; no gross abnormalities were reported.

Quantization • Pre-processing – Adaptive fuzzy c-means automatic brain tissue segmentation method was performed to correct intensity inhomogeneity (Pham & Prince, 1999). • Volumes of white and gray matter were quantitated automatically – Atlas-moderated iterative expectation maximization segmentation algorithm followed by parcellation achieved by nonlinear warping (Gilmore et al. , 2007) – Subject-specific tissue probabilistic maps. • Maximize precision and longitudinally consistency of segmentation results • Parcels aggregated to form whole-brain volume vectors for analysis.

Mapping and Segmentation • Gray and white matter (GM and WM respectively), and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) maps in 2 -year olds were used as probabilistic atlases to guide segmentation of 2 week-old and 1 -year-old images of the same subject using an iterative, simultaneous, registration and segmentation framework. – (Gilmore et al. , 2012; Shi et al. , 2011). • Based on this 4 D segmentation and registration algorithm, GM and WM volumes at were extracted from 90 regions identified at each age. • T 1 images were used for 1 and 2 year olds and T 2 images for neonates.

Present Study: Hypotheses • Characterise Genetic and environmental factors influencing whole-brain volumetric development – Derived separately for gray and for white matter – Neonatal, and 1 - and 2 -years of age • Testing: – Continuities – discontinuities – modes of operation – including gene environment interactions.

Heritability across time • The heritability of volumes may alter with time. – Heritability of IQ increased from childhood into old age (Deary, Spinath, & Bates, 2006) – But… heritability of gray & white matter volumes high in neonates (Gilmore et al. , 2012) • Prediction 1: Heritability at 1 & 2 should exceed that found in neonates. • Contrasting model: Unlike IQ gray and white matter volumes always under strong genetic influence

Shared environments: Magnitude and trajectory • Existing theories make strongly contrasting predictions – Model 1: Large role of shared environment – Model 2: Model 1: Mostly genetic

Model 1: Large role of shared environment • Large role of shared environment on IQ scores prior to school – Olson et al. , 2014; Tucker-Drob et al. , 2011 – SES implicated in brain development • Noble & Farah, 2013 • Predict C increasing with time (and exposure to the rate-limiting environment)

Model 2: Model 1: Mostly genetic • Very high heritability suggests little room for shared environment • Familial influences on brain development may be confounding genetic effects. • Contrasting prediction: minimal shared environment at all three waves.

Developmental Hypotheses: Almost nothing is known • Number of genetic and environmental factors impacting brain development over this period • Time-course – Increasing – Decreasing – Limited to a single ages – Compensatory reversals of effect over time.

One common genetic factor • The generalist genes model of cognitive ability – (Kovas & Plomin, 2006) • Relative lack of genetic innovation in intelligence from pre-school to the teens – (Bartels, Rietveld, Van Baal, & Boomsma, 2002) • Predict that this heritable component will be carried by a single vector.

Alternative hypothesis: Multiple factors: • Unclear how brain development is impacted by the genome during these early periods of rapid growth: – genes act (albeit with diverse mechanisms) so as to exert a monolithic effect – two, three, or more distinct patterns, some with timelimited influence. • Predict: General influences AND time-delimited or gray-white matter specific actions.

Longitudinal impact of family environment • Simplest model suggests a single family environment factor • Significant and constant influence on gray and white matter volumes • Perhaps declining in influence with time.

Canalization model of volume growth • Distinct predictions emerge from models in which brain development is tightly canalized – internal programs causing brain to remain on a programmed course – Able to recover from external shocks or stresses to regain this programmed trajectory via compensatory control mechanisms • (Giedd et al. , 1999; Gilmore et al. , 2010). • Applied to brain development suggests that environmental influences should be impact brain volume, but that these should decay and be reversed.

Impact of Shared environment reversed by canalized growth program • Familial environmental effects compensated (reversed) by canalization processes • Waddington, 1957 • Quantitatively, this would manifest as a factor strongly loading on shared environment, and showing sign-reversal between its neonatal and year 1 and 2 loadings

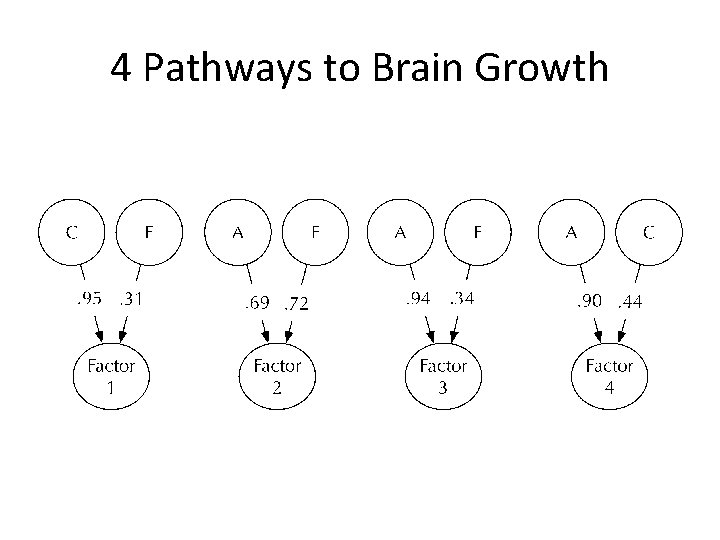

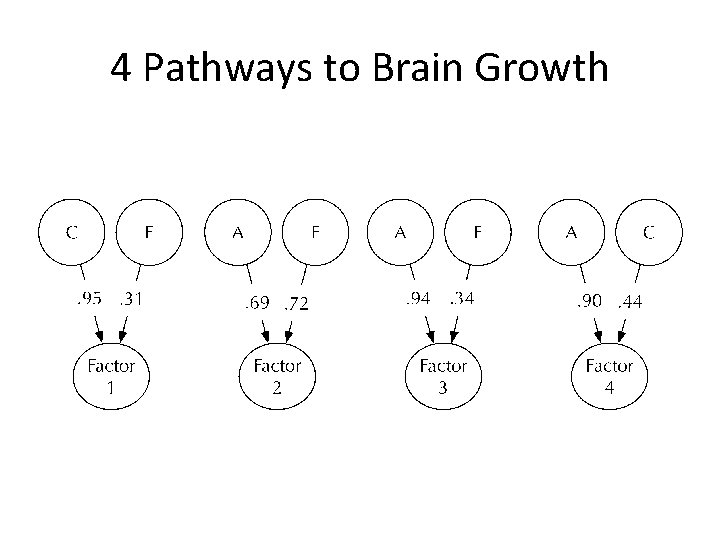

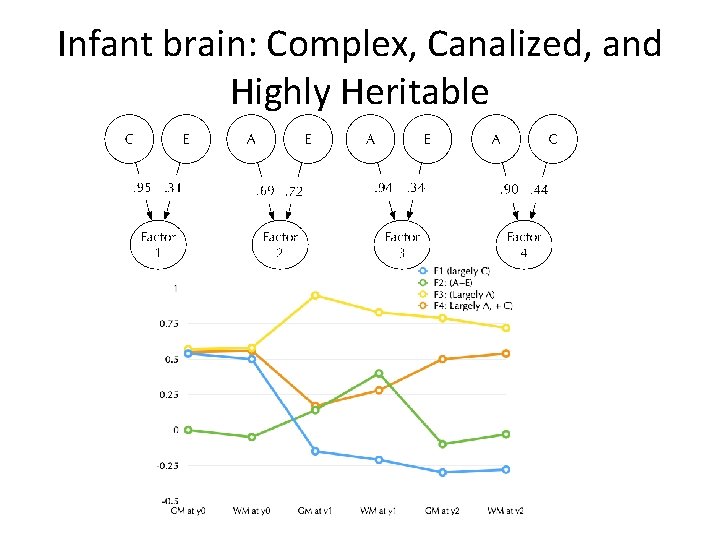

4 Pathways to Brain Growth

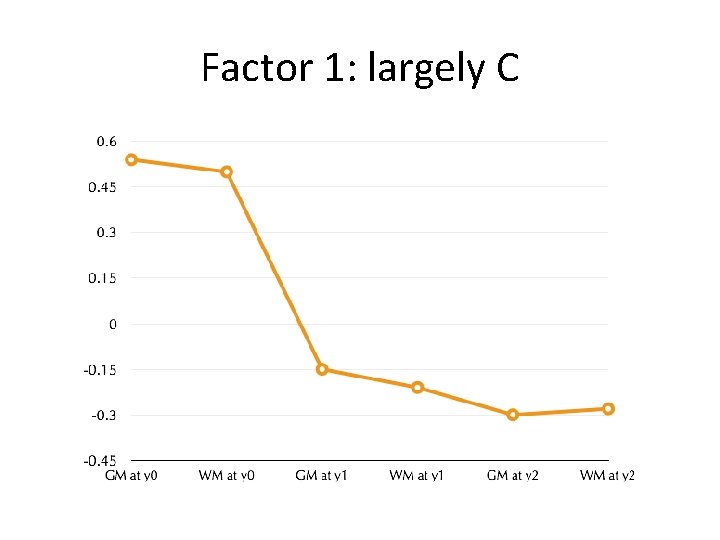

Factor 1: largely C

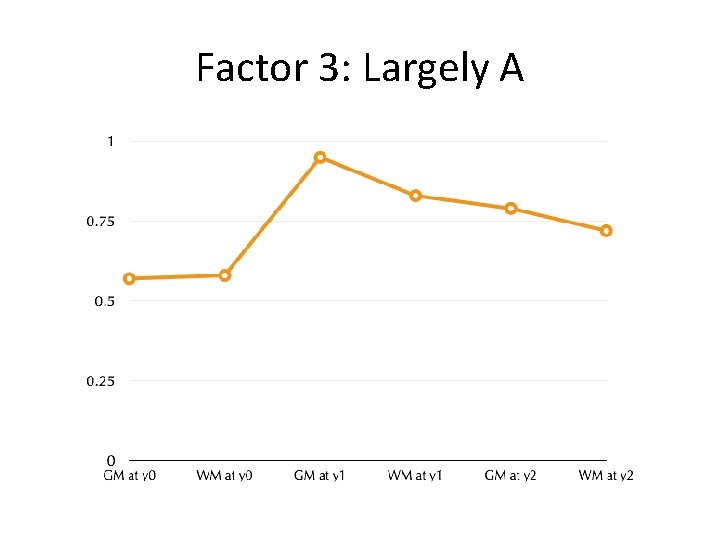

Factor 3: Largely A

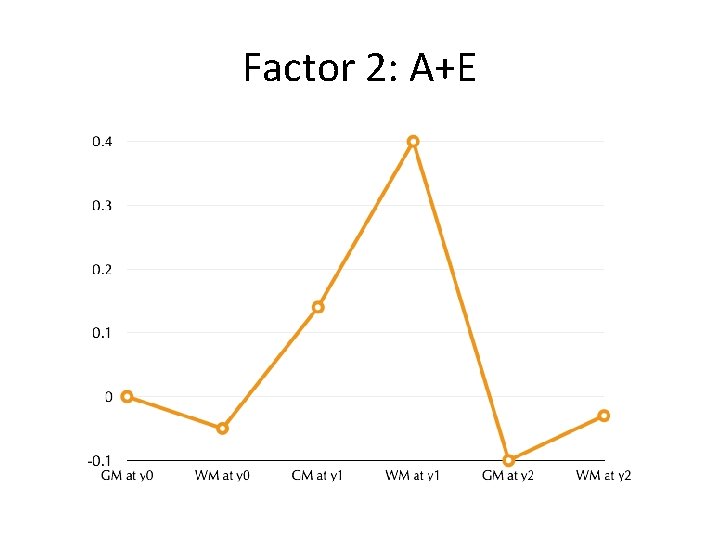

Factor 2: A+E

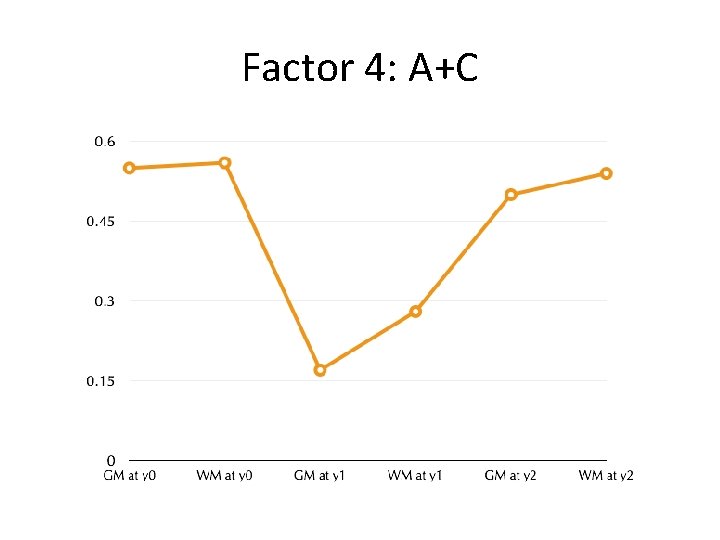

Factor 4: A+C

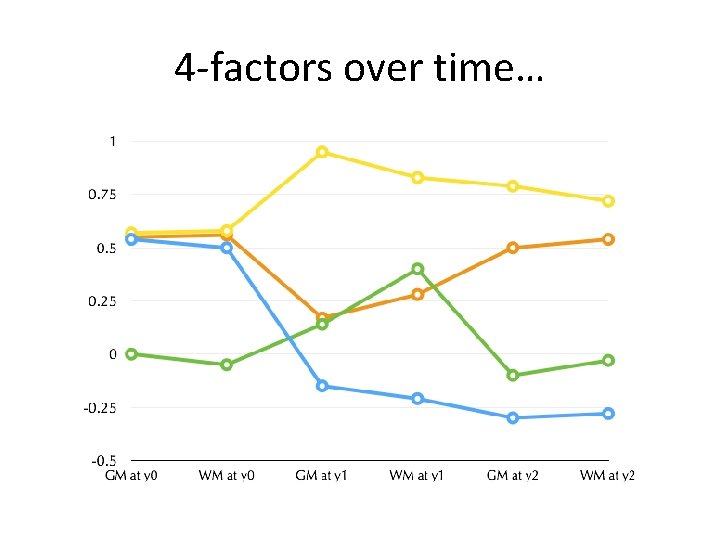

4 -factors over time…

4 Pathways to Brain Growth

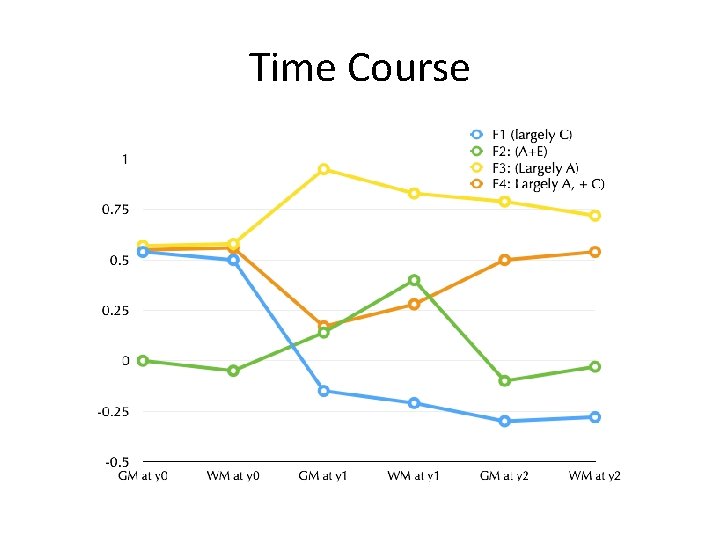

Time Course

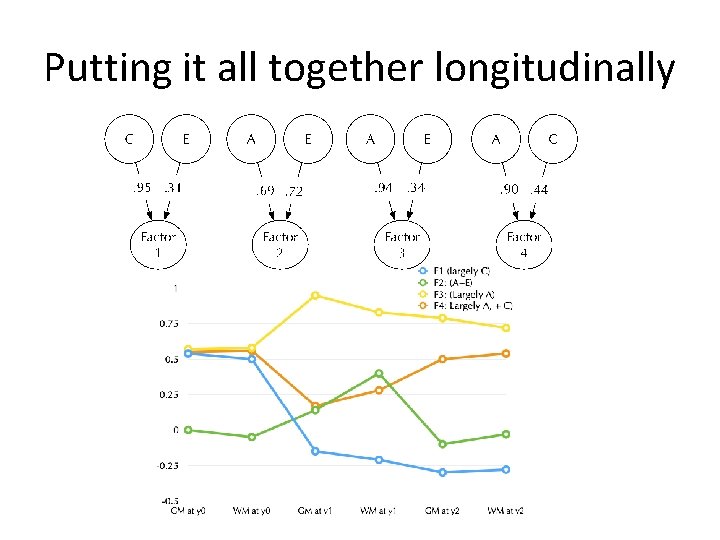

Putting it all together longitudinally

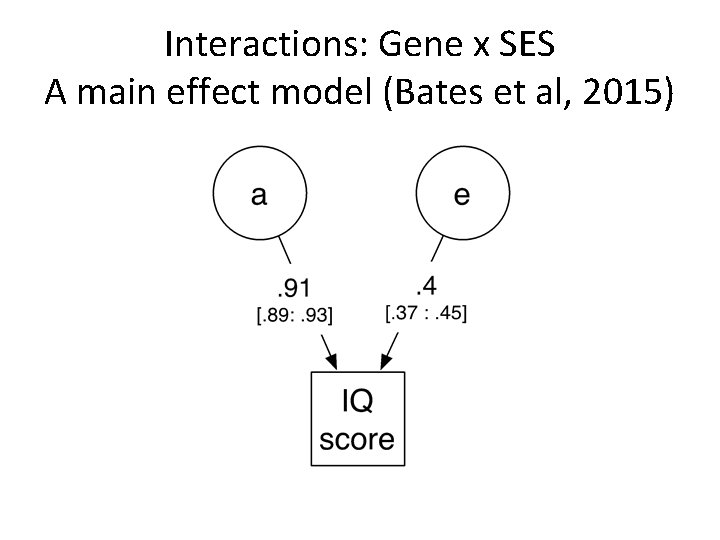

Interactions: Gene x SES A main effect model (Bates et al, 2015)

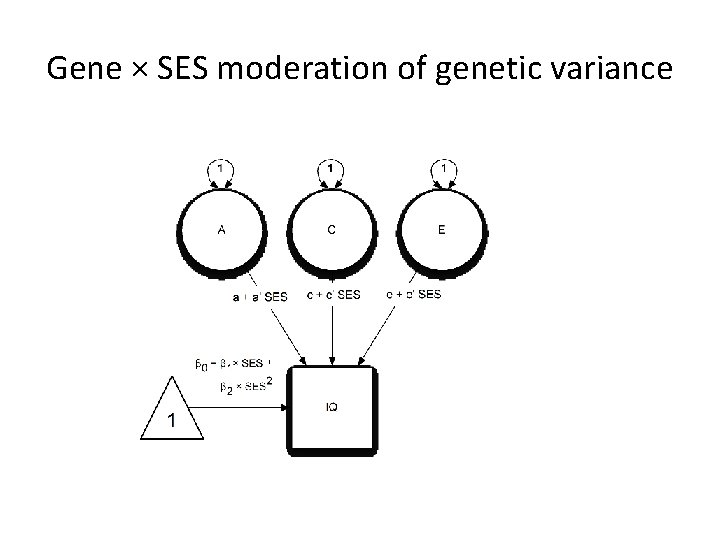

Gene × SES moderation of genetic variance

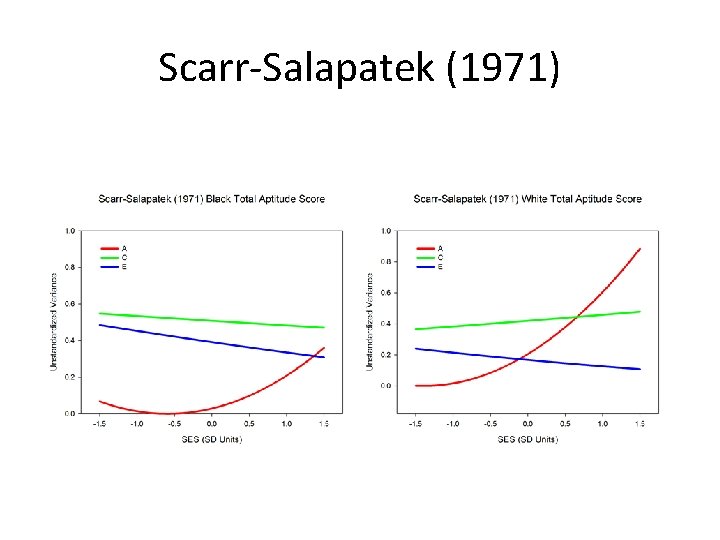

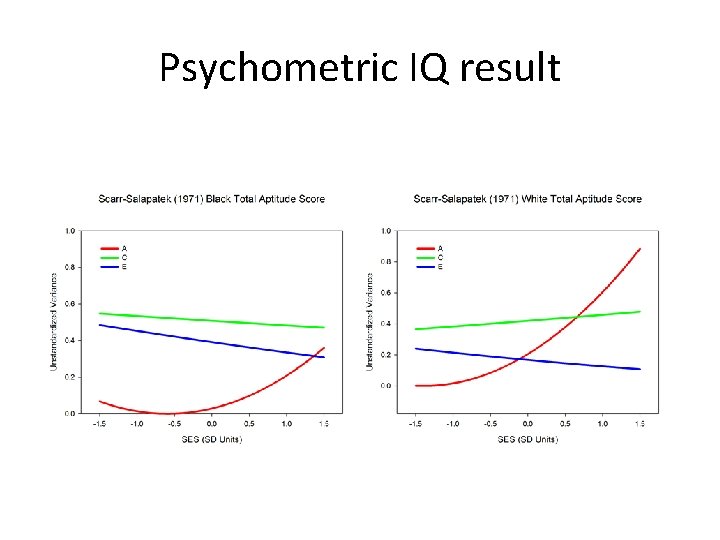

Scarr-Salapatek (1971)

World’s literature (Tucker-Drob & Bates, 2015)

G x SES and Brain Development • Main effect: significant associations of both grayand white-matter volumes with parental SES. • G x SES amplification of children’s genetic potential – Tucker-Drob & Bates, 2015 – Bates, Lewis, & Weiss, 2013 • Predict gene × SES interactions may be present, with increased heritability of brain volumes among higher SES infants.

Logarithmic link of cortical volume to SES (Noble et al. 2015)

Results: No support for G x SES (and reverse/wrong trend)

Psychometric IQ result

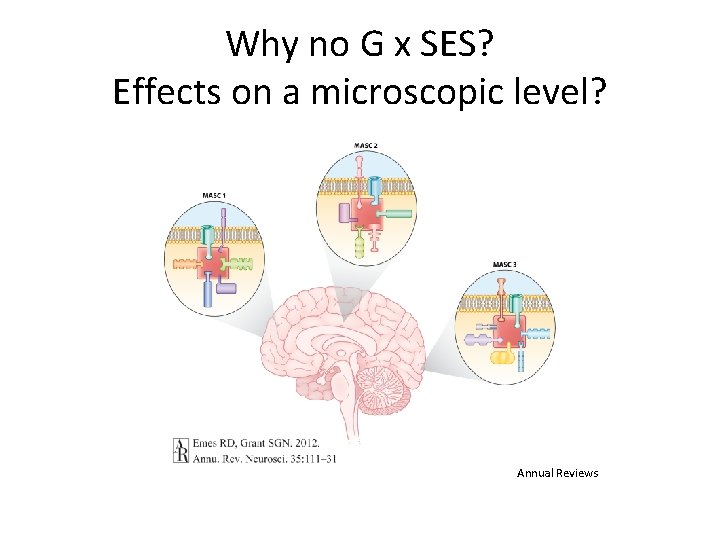

Why no G x SES? Effects on a microscopic level? Annual Reviews

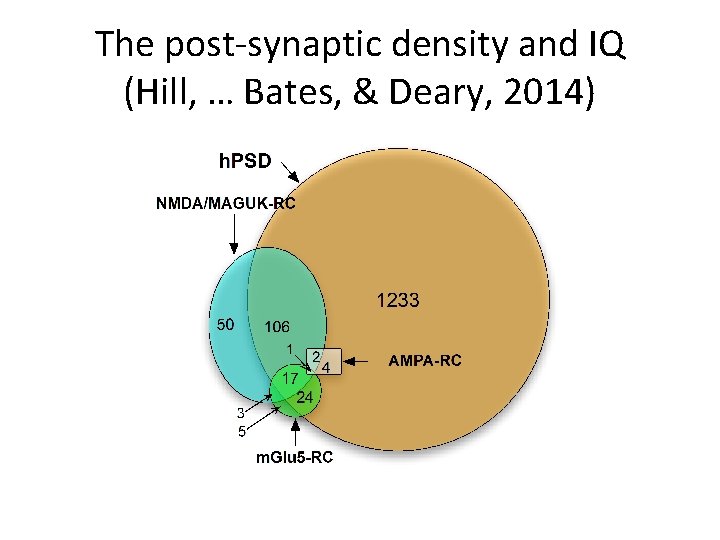

The post-synaptic density and IQ (Hill, … Bates, & Deary, 2014)

Gene interactions later in life? (then why are early years important?

Forbes magazine G S E EN

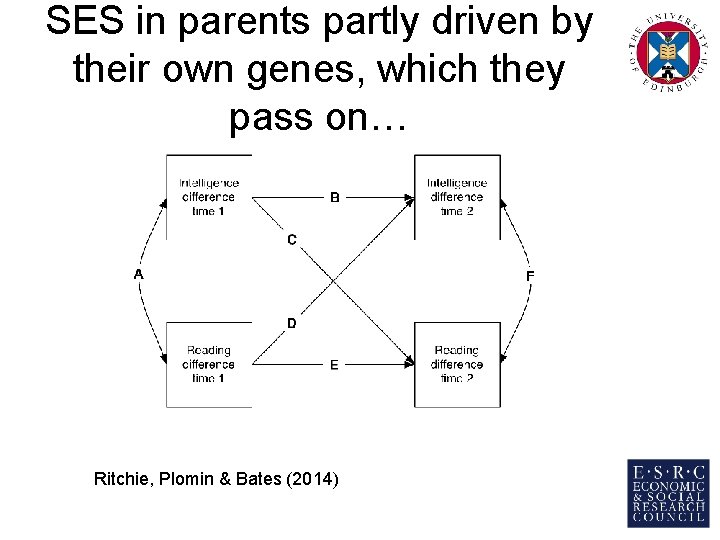

SES in parents partly driven by their own genes, which they pass on… Ritchie, Plomin & Bates (2014)

Summary: No evidence for interaction up to age 3 for gray or white matter

Infant brain: Complex, Canalized, and Highly Heritable

- Slides: 59