Gaussian Process Structural Equation Models with Latent Variables

Gaussian Process Structural Equation Models with Latent Variables RICARDO SILVA ricardo@stats. ucl. ac. uk DEPARTMENT OF STATISTICAL SCIENCE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE LONDON ROBERT B. GRAMACY bobby@statslab. cam. ac. uk STATISTICAL LABORATORY UNIVERSITY OF CAMBRIDGE

Summary �A Bayesian approach for graphical models with measurement error �Model: nonparametric DAG + linear measurement model Related literature: structural equation models (SEM), error-invariables regression �Applications: dimensionality reduction, density estimation, causal inference Evaluation: social sciences/marketing data, biological domain �Approach: Gaussian process prior + MCMC Bayesian pseudo-inputs model + space-filling priors

An Overview of Measurement Error Problems

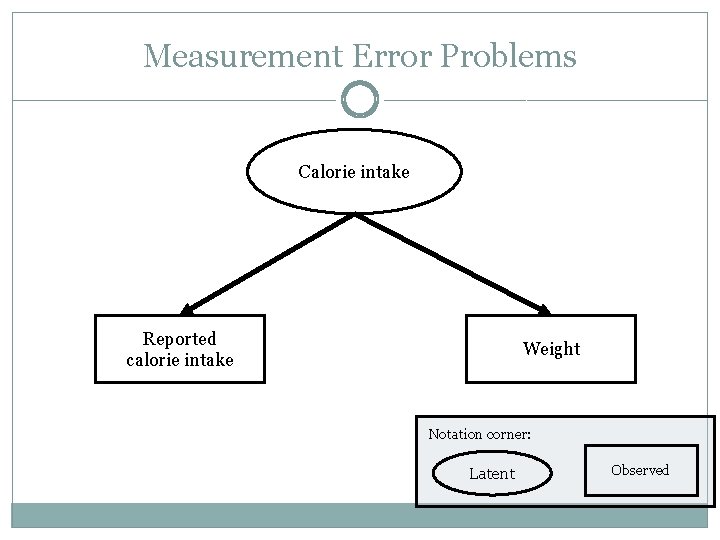

Measurement Error Problems Calorie intake Weight

Measurement Error Problems Calorie intake Reported calorie intake Weight Notation corner: Latent Observed

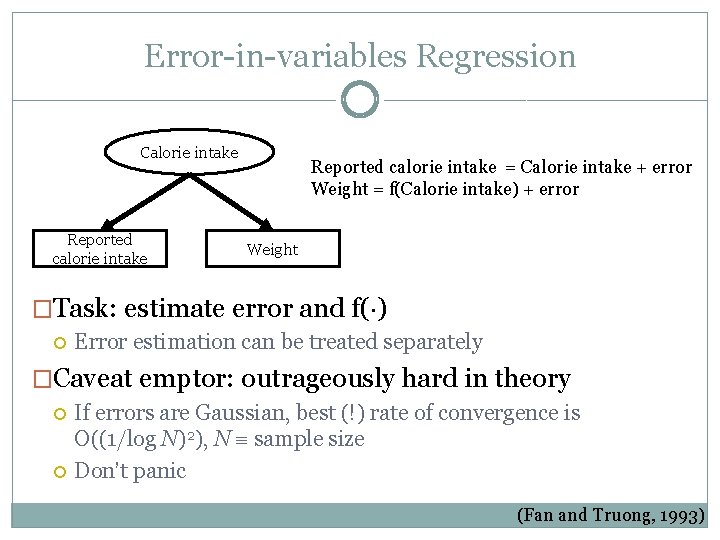

Error-in-variables Regression Calorie intake Reported calorie intake = Calorie intake + error Weight = f(Calorie intake) + error Weight �Task: estimate error and f( ) Error estimation can be treated separately �Caveat emptor: outrageously hard in theory If errors are Gaussian, best (!) rate of convergence is O((1/log N)2), N sample size Don’t panic (Fan and Truong, 1993)

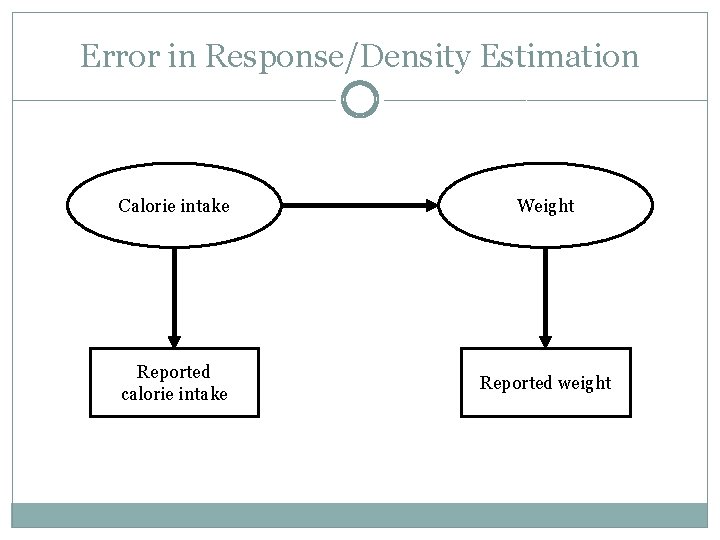

Error in Response/Density Estimation Calorie intake Weight Reported calorie intake Reported weight

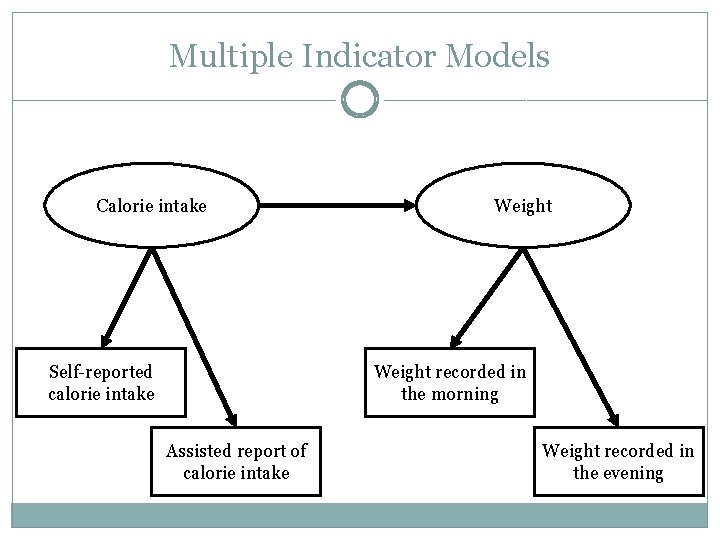

Multiple Indicator Models Calorie intake Self-reported calorie intake Weight recorded in the morning Assisted report of calorie intake Weight recorded in the evening

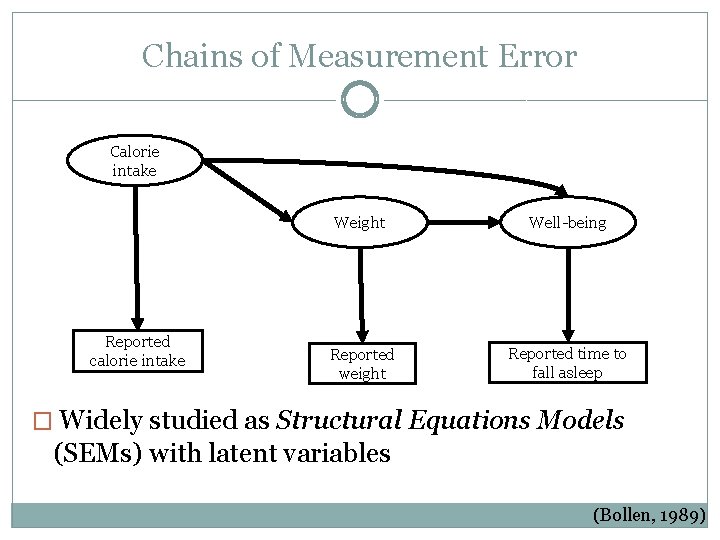

Chains of Measurement Error Calorie intake Reported calorie intake Weight Well-being Reported weight Reported time to fall asleep � Widely studied as Structural Equations Models (SEMs) with latent variables (Bollen, 1989)

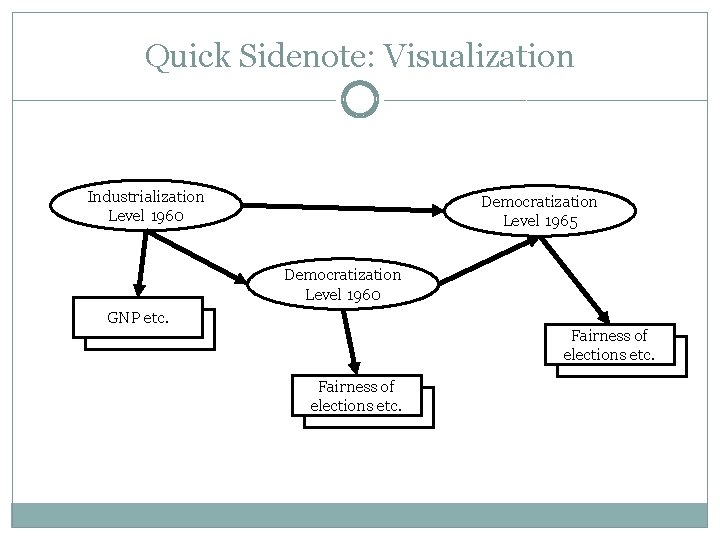

Quick Sidenote: Visualization Industrialization Level 1960 Democratization Level 1965 Democratization Level 1960 GNP etc. Fairness of elections etc. GNP etc.

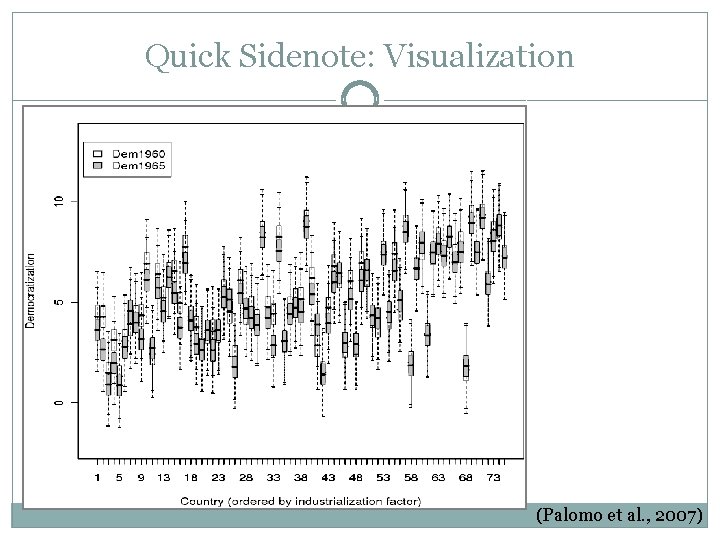

Quick Sidenote: Visualization (Palomo et al. , 2007)

Non-parametric SEM: Model and Inference

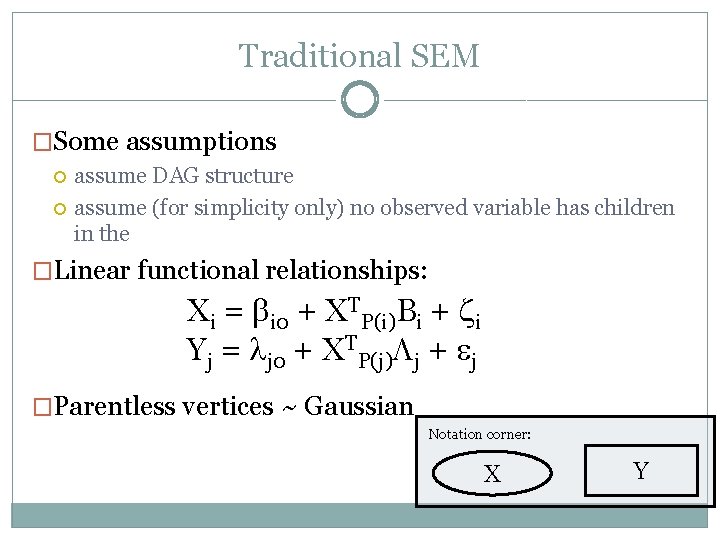

Traditional SEM �Some assumptions assume DAG structure assume (for simplicity only) no observed variable has children in the �Linear functional relationships: Xi = i 0 + XTP(i)Bi + i Yj = j 0 + XTP(j) j + j �Parentless vertices ~ Gaussian Notation corner: X Y

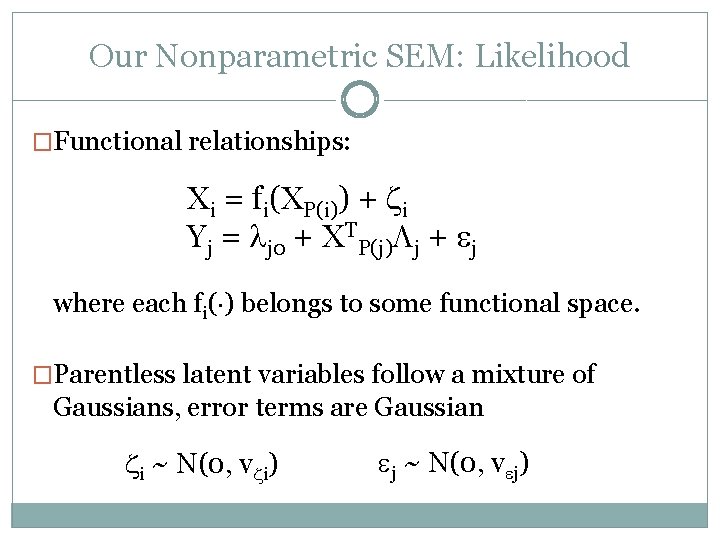

Our Nonparametric SEM: Likelihood �Functional relationships: Xi = fi(XP(i)) + i Yj = j 0 + XTP(j) j + j where each fi( ) belongs to some functional space. �Parentless latent variables follow a mixture of Gaussians, error terms are Gaussian i ~ N(0, v i) j ~ N(0, v j)

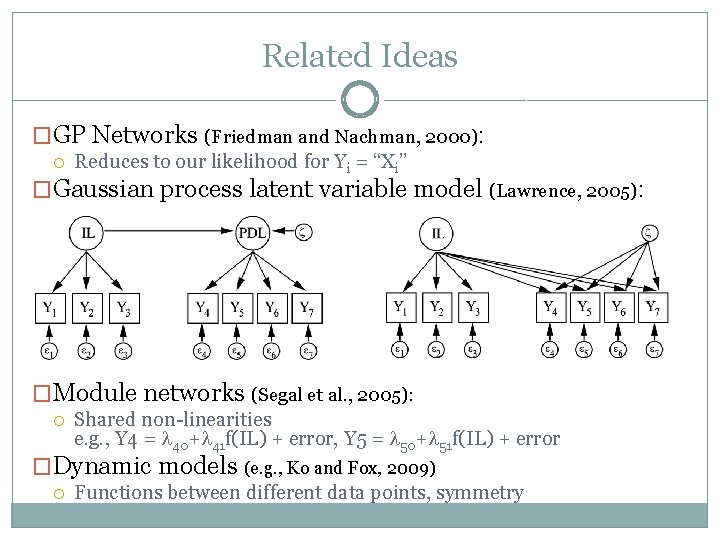

Related Ideas �GP Networks (Friedman and Nachman, 2000): Reduces to our likelihood for Yi = “Xi” �Gaussian process latent variable model (Lawrence, 2005): �Module networks (Segal et al. , 2005): Shared non-linearities e. g. , Y 4 = 40+ 41 f(IL) + error, Y 5 = 50+ 51 f(IL) + error �Dynamic models (e. g. , Ko and Fox, 2009) Functions between different data points, symmetry

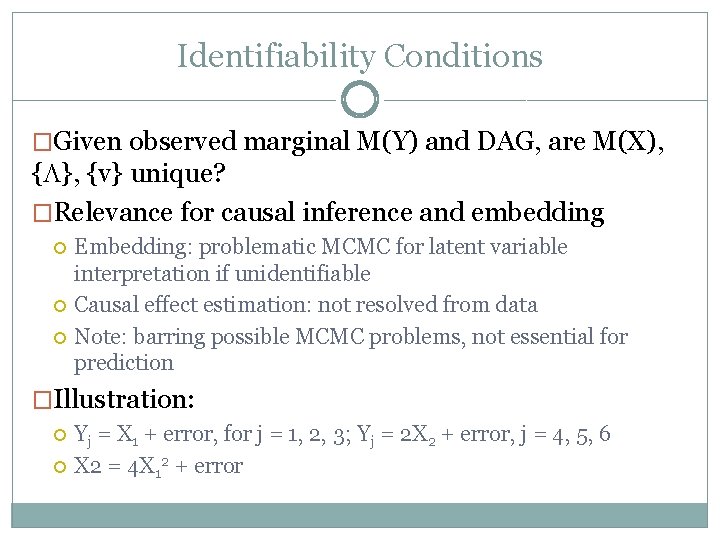

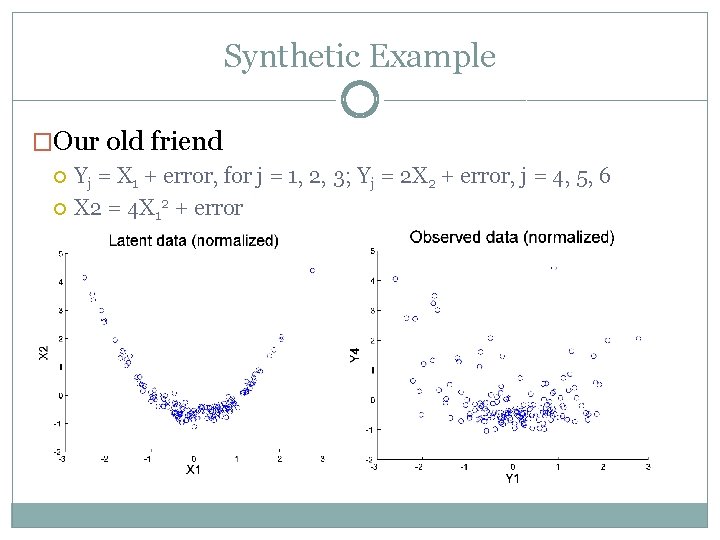

Identifiability Conditions �Given observed marginal M(Y) and DAG, are M(X), { }, {v} unique? �Relevance for causal inference and embedding Embedding: problematic MCMC for latent variable interpretation if unidentifiable Causal effect estimation: not resolved from data Note: barring possible MCMC problems, not essential for prediction �Illustration: Yj = X 1 + error, for j = 1, 2, 3; Yj = 2 X 2 + error, j = 4, 5, 6 X 2 = 4 X 12 + error

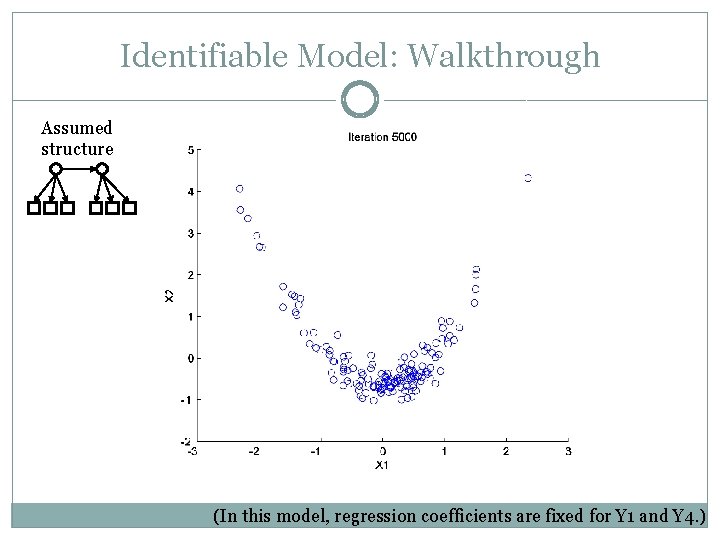

Identifiable Model: Walkthrough Assumed structure (In this model, regression coefficients are fixed for Y 1 and Y 4. )

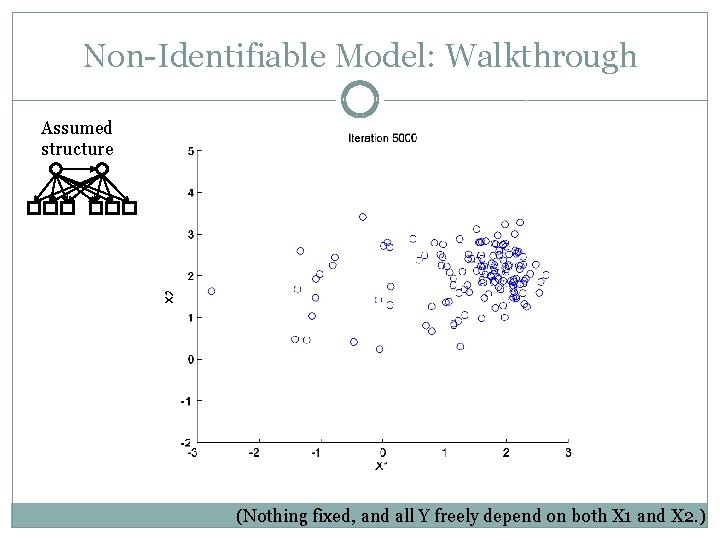

Non-Identifiable Model: Walkthrough Assumed structure (Nothing fixed, and all Y freely depend on both X 1 and X 2. )

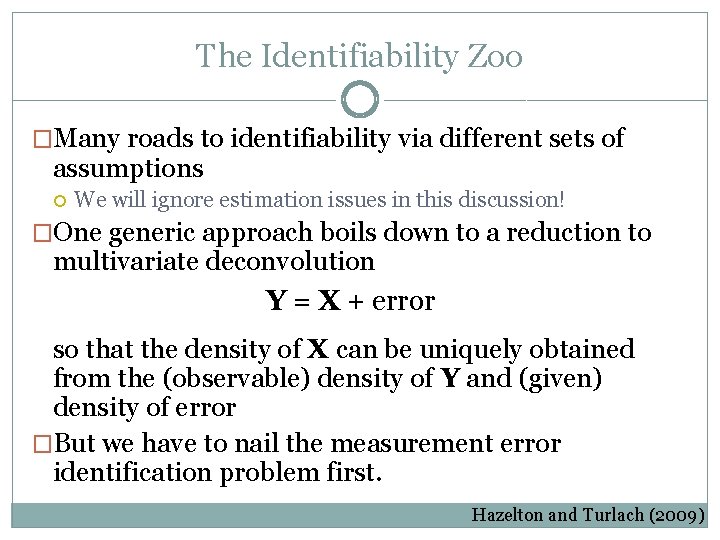

The Identifiability Zoo �Many roads to identifiability via different sets of assumptions We will ignore estimation issues in this discussion! �One generic approach boils down to a reduction to multivariate deconvolution Y = X + error so that the density of X can be uniquely obtained from the (observable) density of Y and (given) density of error �But we have to nail the measurement error identification problem first. Hazelton and Turlach (2009)

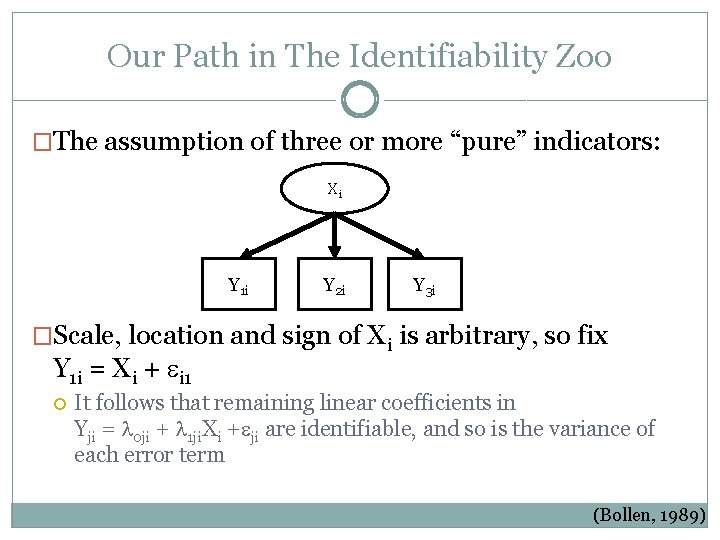

Our Path in The Identifiability Zoo �The assumption of three or more “pure” indicators: Xi Y 1 i Y 2 i Y 3 i �Scale, location and sign of Xi is arbitrary, so fix Y 1 i = Xi + i 1 It follows that remaining linear coefficients in Yji = 0 ji + 1 ji. Xi + ji are identifiable, and so is the variance of each error term (Bollen, 1989)

Our Path in The Identifiability Zoo �Select one pure indicator per latent variable to form set Y 1 (Y 11, Y 12, . . . , Y 1 L) and E 1 ( 11, 12, . . . , 1 L) �From Y 1 = X + E 1 obtain the density of X, since Gaussian assumption for error terms results in density of E 1 being known �Notice: since density of X is identifiable, identifiability of directionality Xi Xj vs. Xj Xi is achievable in theory (Hoyer et al. , 2008)

Quick Sidenote: Other Paths �Three “pure indicators” per variable might not be reasonable �Alternatives: Two pure indicators, non-zero correlation between latent variables Repeated measurements (e. g. , Schennach 2004) � X* = X + error � X** = X + error � Y = f(X) + error Also related: results on detecting presence of measurement error (Janzing et al. , 2009) For more: Econometrica, etc.

Priors: Parametric Components �Measurement model: standard linear regression priors e. g. , Gaussian prior for coefficients, inverse gamma for conditional variance Could use the standard normal-gamma priors so that measurement model parameters are marginalized Samples using P(Y | X, f(X))p(X, f(X)) instead of P(Y | X, f(X), )p(X, f(X))p( ) In the experiments, we won’t use such normal-gamma priors, though, because we want to evaluate mixing in general

Priors: Nonparametric Components �Function f(XPa(i)): Gaussian process prior f(XPa(i)(1)), f(XPa(i) (2)), . . . , f(XPa(i) (N)) ~ jointly Gaussian with particular kernel function �Computational issues: Scales as O(N 3), N being sample size Standard MCMC might converge poorly due to high conditional association between latent variables

The Pseudo-Inputs Model �Hierarchical approach �Recall: standard GP from {X(1), X(2), . . . , X(N)}, obtain distribution over {f(X(1)), f(X(2)), . . . , f(X(N))} �Predictions of “future” observations f(X*(1)), f(X*(2)), . . . , etc. are jointly conditionally Gaussian too �Idea: imagine you see a pseudo training set X your “actual” training set {f(X(1)), f(X(2)), . . . , f(X(N))} is conditionally Gaussian given X however, drop all off-diagonal elements of the conditional covariance matrix (Snelson and Ghahramani, 2006; Banerjee et al. , 2008)

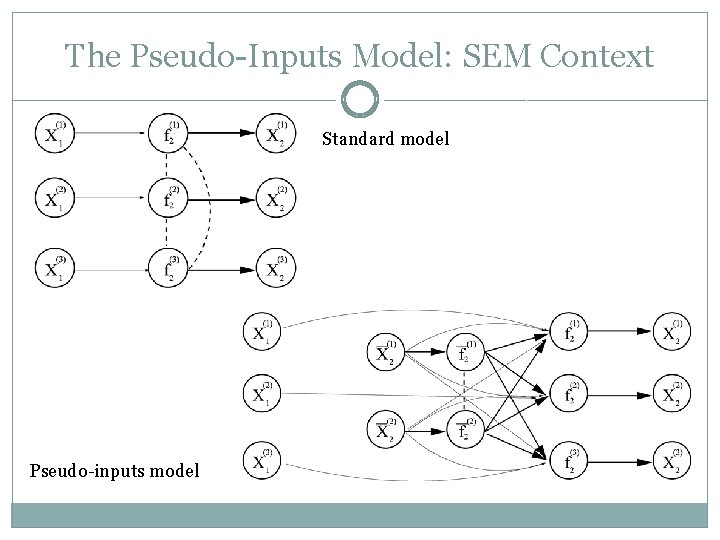

The Pseudo-Inputs Model: SEM Context Standard model Pseudo-inputs model

Bayesian Pseudo-Inputs Treatment �Snelson and Ghaharamani (2006): empirical Bayes estimator for pseudo-inputs Pseudo-inputs rapidly amounts to many more free parameters sometimes prone to overfitting �Here: “space-filling” prior Let pseudo-inputs X have bounded support Set p(Xi) det(D), where D is some kernel matrix �A priori, “spreads” points in some hyper-cube �No fitting: pseudo-inputs are sampled too Essentially no (asymptotic) extra cost since we have to sample latent variables anyway Possible mixing problems? REFERENCES HERE

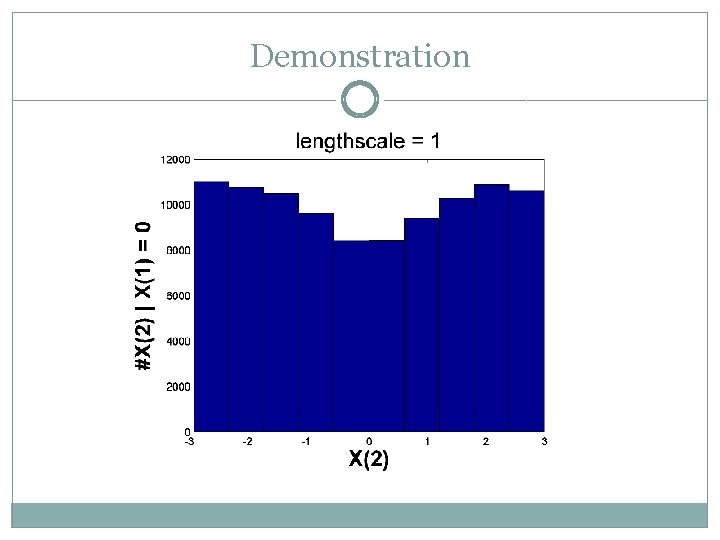

Demonstration �Squared exponential kernel, hyperparameter l exp(–|xi – xj|2 / l) � 1 -dimensional pseudo-input space, 2 pseudo-data points X(1), X(2) �Fix X(1) to zero, sample X(2) NOT independent. It should differ from the uniform distribution at different degrees according to l

Demonstration

More on Priors and Pseudo-Points �Having a prior treats overfitting “blurs” pseudo-inputs, which theoretically leads to a bigger coverage if number of pseudo-inputs is “insufficient, ” might provide some edge over models with fixed pseudo-inputs, but care should be exercised �Example Synthetic data with quadratic relationship

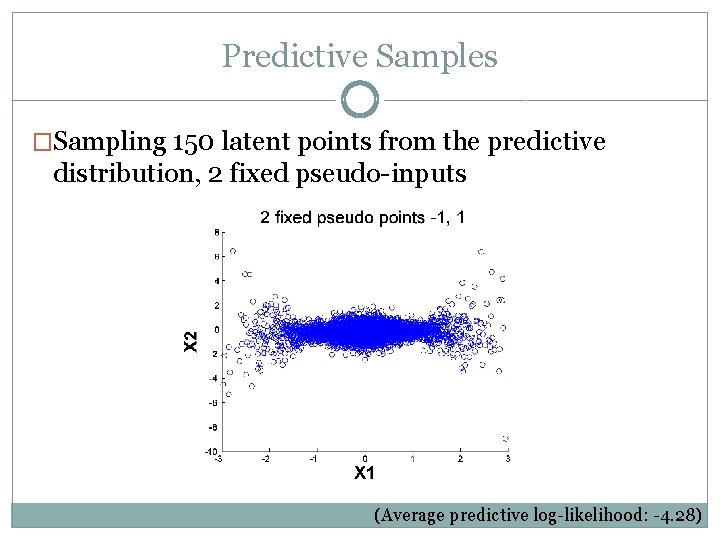

Predictive Samples �Sampling 150 latent points from the predictive distribution, 2 fixed pseudo-inputs (Average predictive log-likelihood: -4. 28)

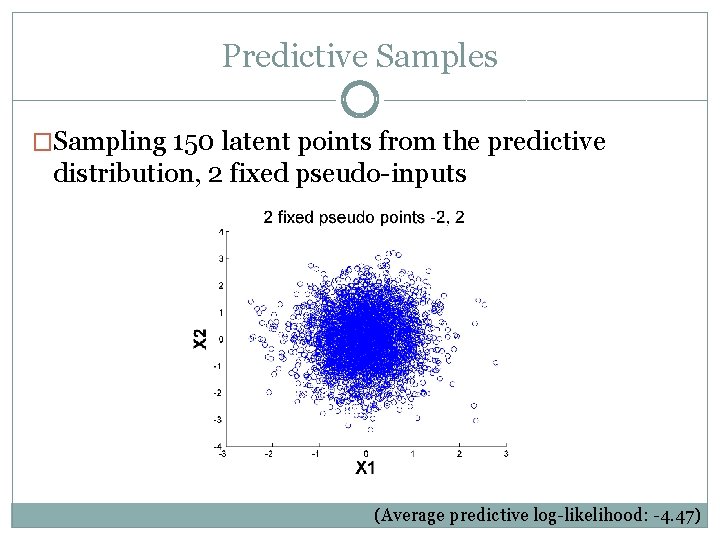

Predictive Samples �Sampling 150 latent points from the predictive distribution, 2 fixed pseudo-inputs (Average predictive log-likelihood: -4. 47)

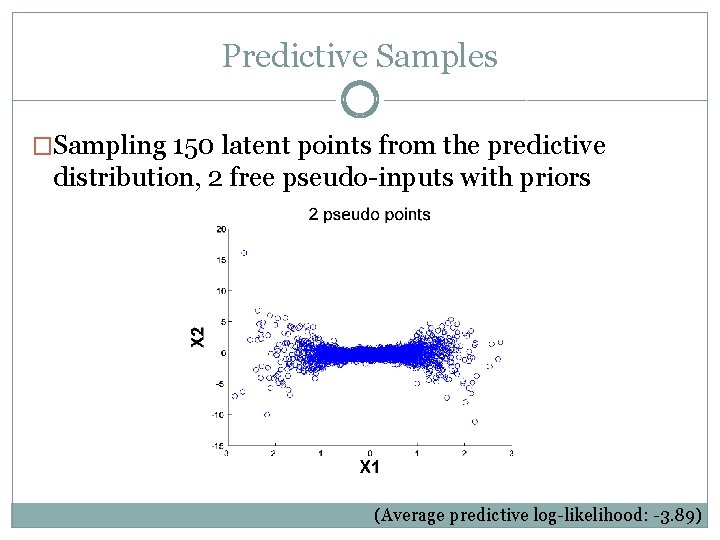

Predictive Samples �Sampling 150 latent points from the predictive distribution, 2 free pseudo-inputs with priors (Average predictive log-likelihood: -3. 89)

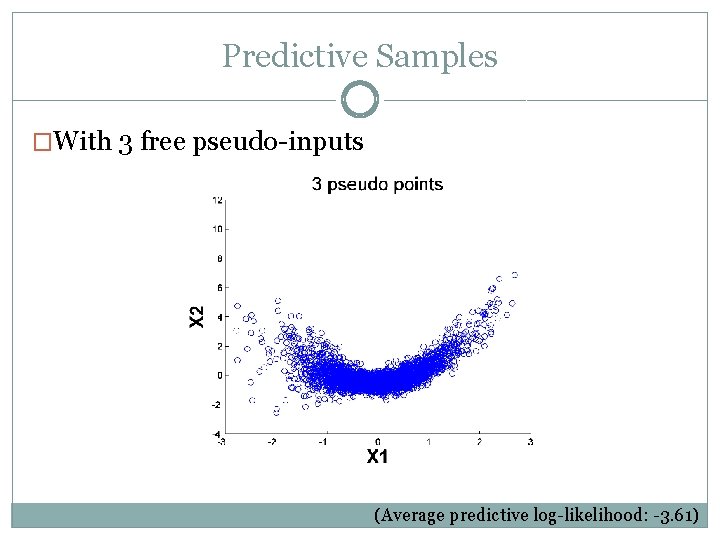

Predictive Samples �With 3 free pseudo-inputs (Average predictive log-likelihood: -3. 61)

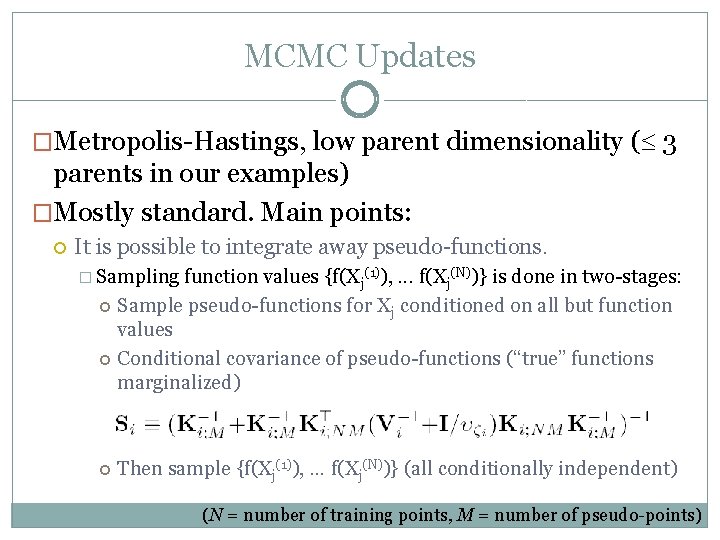

MCMC Updates �Metropolis-Hastings, low parent dimensionality ( 3 parents in our examples) �Mostly standard. Main points: It is possible to integrate away pseudo-functions. � Sampling function values {f(Xj(1)), . . . f(Xj(N))} is done in two-stages: Sample pseudo-functions for Xj conditioned on all but function values Conditional covariance of pseudo-functions (“true” functions marginalized) Then sample {f(Xj(1)), . . . f(Xj(N))} (all conditionally independent) (N = number of training points, M = number of pseudo-points)

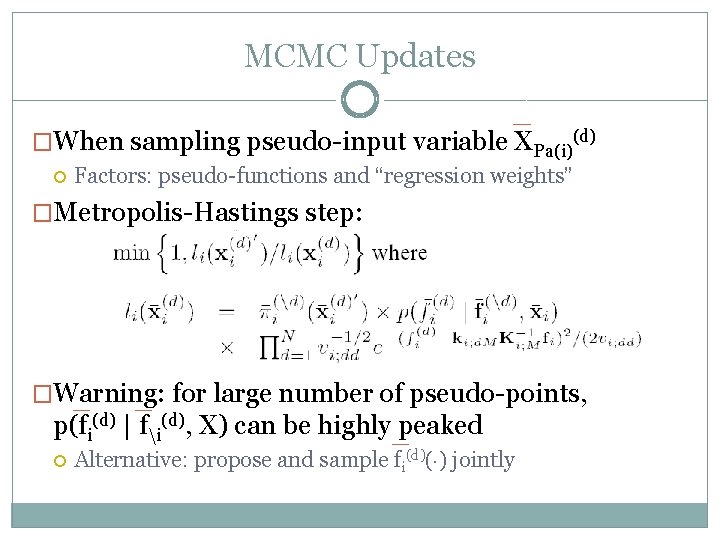

MCMC Updates �When sampling pseudo-input variable XPa(i)(d) Factors: pseudo-functions and “regression weights” �Metropolis-Hastings step: �Warning: for large number of pseudo-points, p(fi(d) | fi(d), X) can be highly peaked Alternative: propose and sample fi(d)( ) jointly

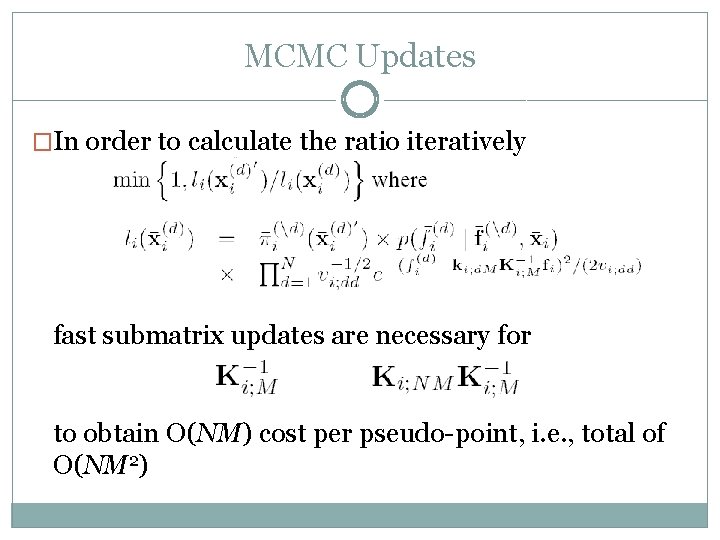

MCMC Updates �In order to calculate the ratio iteratively fast submatrix updates are necessary for to obtain O(NM) cost per pseudo-point, i. e. , total of O(NM 2)

Experiments

Setup �Evaluation of Markov chain behaviour �“Objective” model evaluation via predictive log- likelihood �Quick details Squared exponential kernel Prior for a (and b): mixture of Gamma (1, 20) + Gamma(20, 20) M = 50

Synthetic Example �Our old friend Yj = X 1 + error, for j = 1, 2, 3; Yj = 2 X 2 + error, j = 4, 5, 6 X 2 = 4 X 12 + error

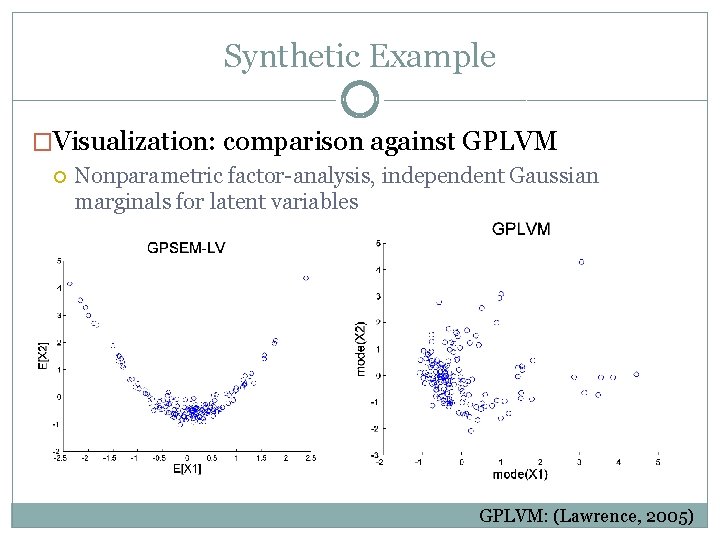

Synthetic Example �Visualization: comparison against GPLVM Nonparametric factor-analysis, independent Gaussian marginals for latent variables GPLVM: (Lawrence, 2005)

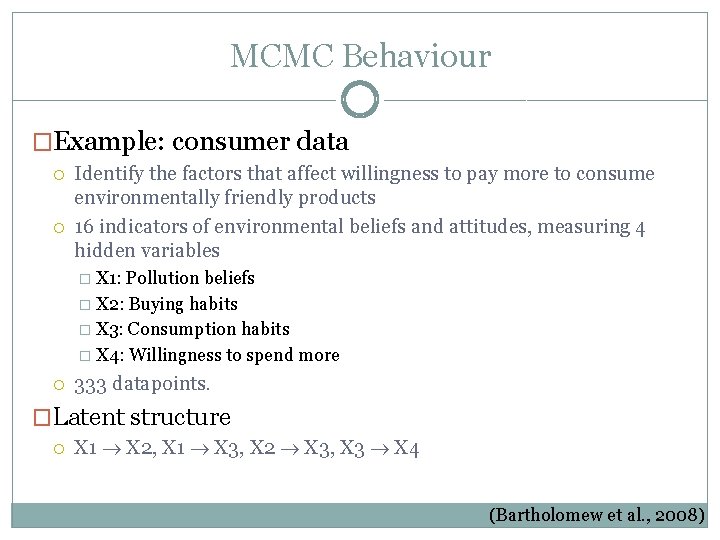

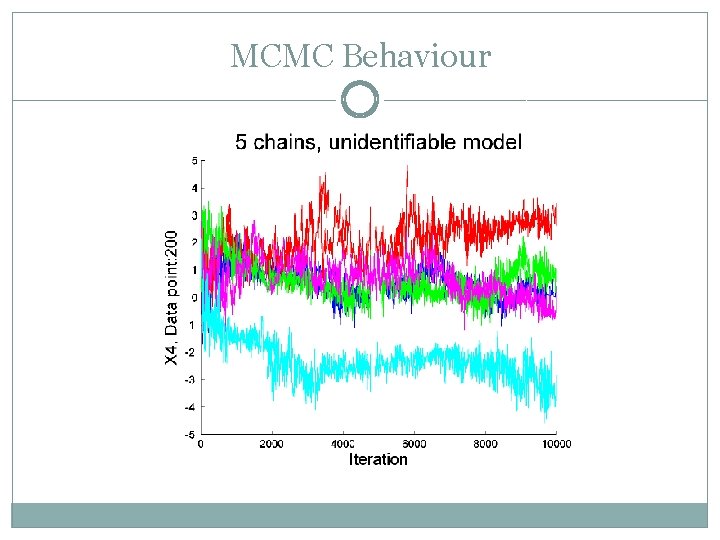

MCMC Behaviour �Example: consumer data Identify the factors that affect willingness to pay more to consume environmentally friendly products 16 indicators of environmental beliefs and attitudes, measuring 4 hidden variables � X 1: Pollution beliefs � X 2: Buying habits � X 3: Consumption habits � X 4: Willingness to spend more 333 datapoints. �Latent structure X 1 X 2, X 1 X 3, X 2 X 3, X 3 X 4 (Bartholomew et al. , 2008)

MCMC Behaviour

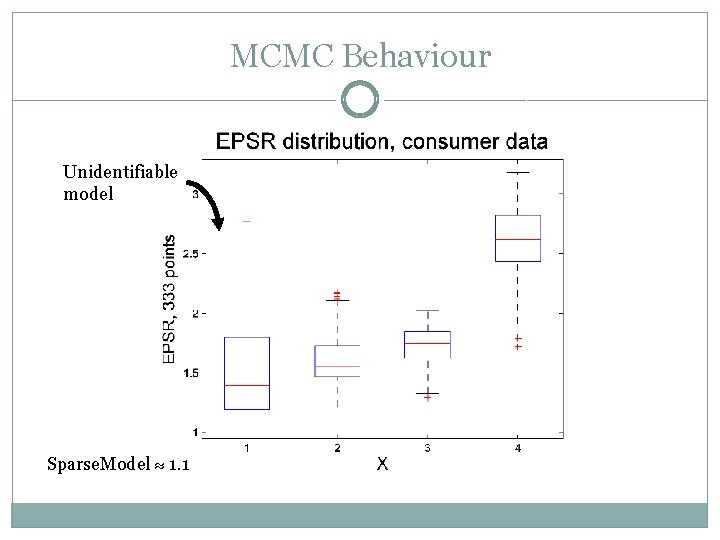

MCMC Behaviour Unidentifiable model Sparse. Model 1. 1

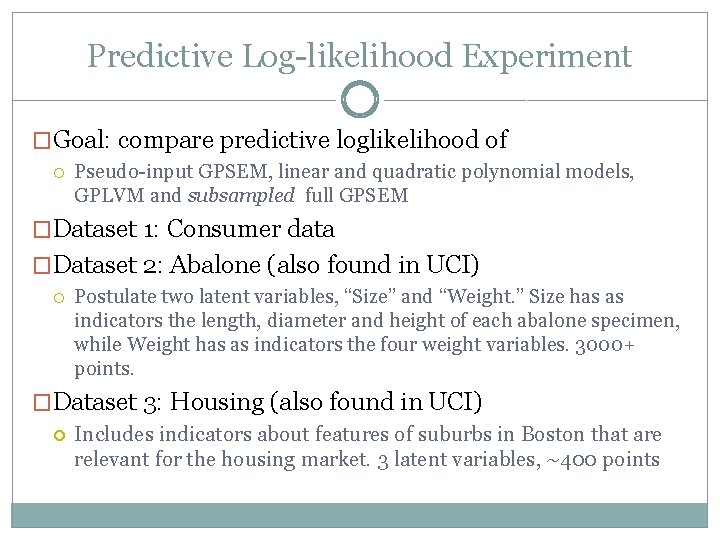

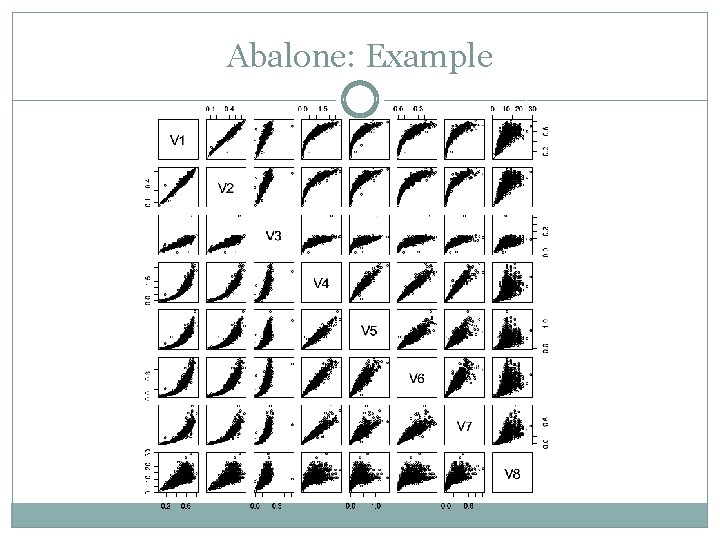

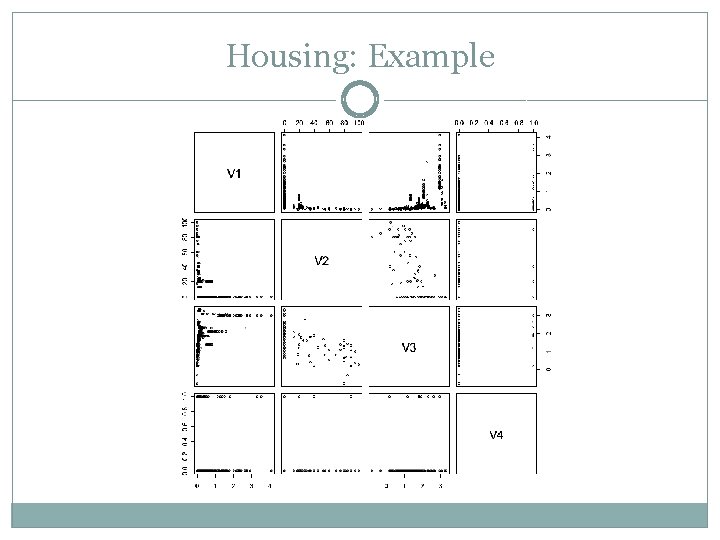

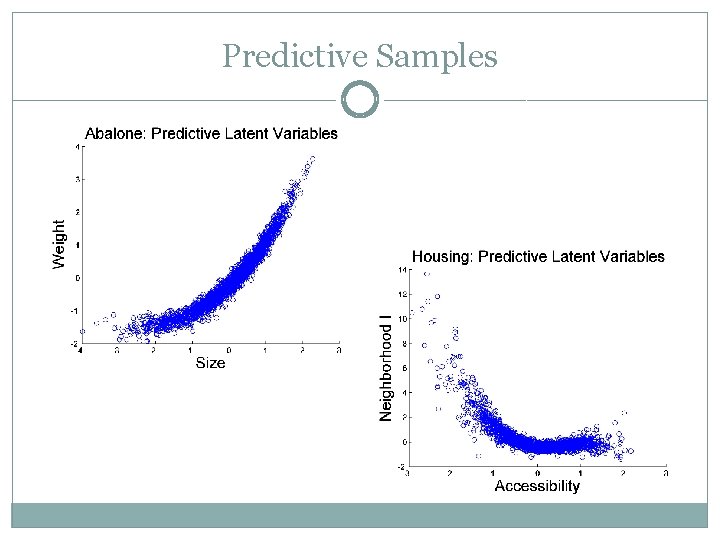

Predictive Log-likelihood Experiment �Goal: compare predictive loglikelihood of Pseudo-input GPSEM, linear and quadratic polynomial models, GPLVM and subsampled full GPSEM �Dataset 1: Consumer data �Dataset 2: Abalone (also found in UCI) Postulate two latent variables, “Size” and “Weight. ” Size has as indicators the length, diameter and height of each abalone specimen, while Weight has as indicators the four weight variables. 3000+ points. �Dataset 3: Housing (also found in UCI) Includes indicators about features of suburbs in Boston that are relevant for the housing market. 3 latent variables, ~400 points

Abalone: Example

Housing: Example

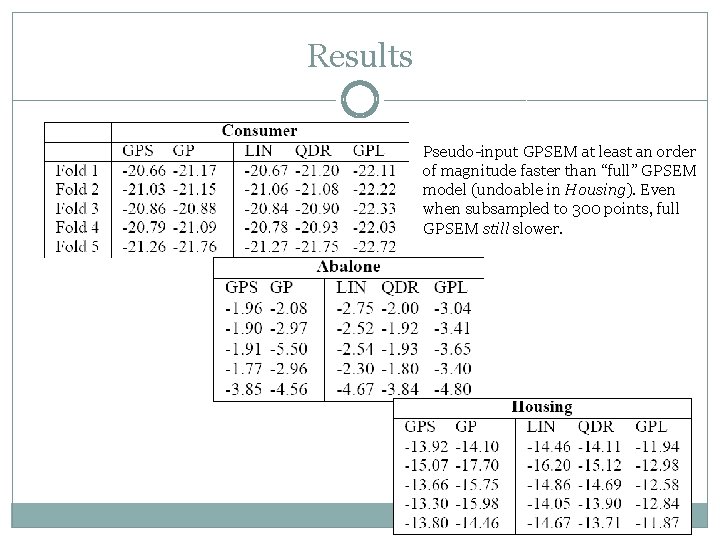

Results Pseudo-input GPSEM at least an order of magnitude faster than “full” GPSEM model (undoable in Housing). Even when subsampled to 300 points, full GPSEM still slower.

Predictive Samples

Conclusion and Future Work �Even Metropolis-Hastings does a somewhat decent job (for sparse models) Potential problems with ordinal/discrete data. �Evaluation of high-dimensional models �Structure learning �Hierarchical models �Comparisons against random projection approximations mixture of Gaussian processes with limited mixture size �Full MATLAB code available

Acknowledgements �Thanks to Patrik Hoyer, Ed Snelson and Irini Moustaki.

Extra References (not in the paper) �S. Banerjee, A. Gelfand, A. Finley and H. Sang (2008). “Gaussian predictive process models for large spatial data sets”. JRSS B. �D. Janzing, J. Peters, J. M. Mooij and B. Schölkopf. (2009). Identifying confounders using additive noise models. UAI. �M. Hazelton and B. Turlach (2009). “Nonparametric density deconvolution by weighted kernel estimators”. Statistics and Computing. �S. Schennack (2004). “Estimation of nonlinear models with measurement error”. Econometric 72.

- Slides: 52