Game Programming Algorithms and Techniques Chapter 7 Physics

- Slides: 48

Game Programming Algorithms and Techniques Chapter 7 Physics

Chapter 7 Objectives § § § Planes, Rays, and Line Segments – Learn about additional geometric objects that are useful for physics systems Collision Geometry – How do we simplify geometry for collision tests? Collision Detection – Various instantaneous collision checks as well as continuous checks Physics-Based Movement – Linear mechanics – Numeric integration Brief rundown of physics middleware

Planes § § § A plane is a flat, two-dimensional surface that extends infinitely. In a game, we might use planes to abstract the ground, walls, and so on. Plane equation: – – – P is a point on the plane. n-hat is the normal of the plane. d is the minimum distance between the plane and the origin.

Planes, Cont'd § § Given a triangle, it is straightforward to construct a plane: – P is any point on the plane, and we know any of the three vertices of the triangle satisfy this. – The normal can be computed from a plane, as covered in Chapter 4. – Once we have both P and n-hat, we can calculate d. Games will usually store n-hat and d in memory: struct Plane Vector 3 normal float d end

Rays § A ray starts at a specific point and travels infinitely in a direction. § Can be represented by a parametric equation: – – – t >= 0. R 0 is the starting point of the plane. v is the direction of the ray.

Line Segments § § A line segment starts at one point and ends at another. Given a start point P 0 and an end point P 1, we can solve for v: § Then we just restrict t to be between 0 and 1.

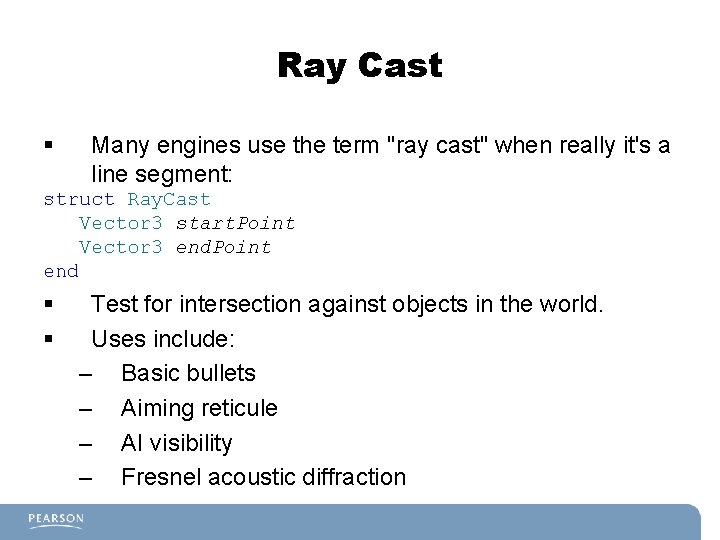

Ray Cast § Many engines use the term "ray cast" when really it's a line segment: struct Ray. Cast Vector 3 start. Point Vector 3 end. Point end § § Test for intersection against objects in the world. Uses include: – Basic bullets – Aiming reticule – AI visibility – Fresnel acoustic diffraction

Collision Geometry § The goal is to simplify objects for testing whether they intersect with each other. § There a number of simplified representations we might use, some more computationally expensive than others. § Often we might use multiple levels of collision geometry, from less accurate to more accurate.

Bounding Sphere § The simplest type of collision geometry used § Very fast to check the intersection between two bounding spheres § Simple to represent: class Bounding. Sphere Vector 3 center float radius end

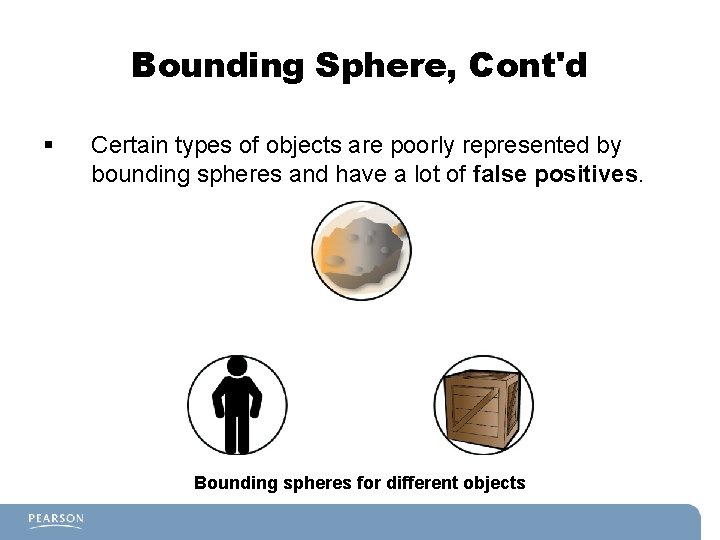

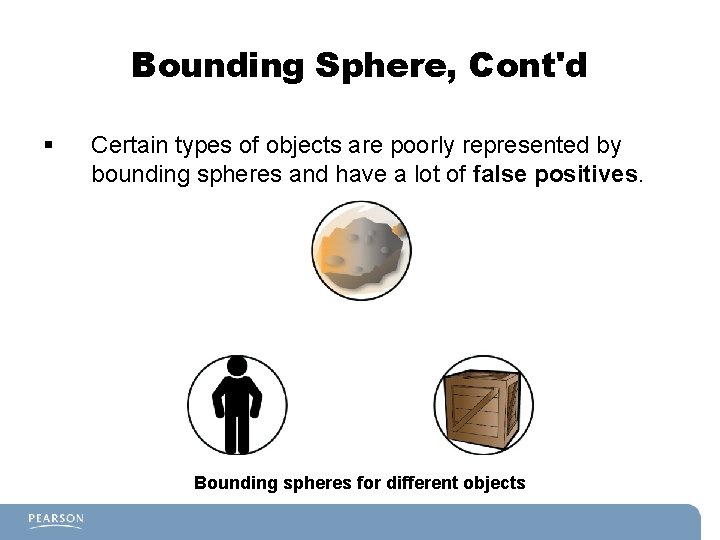

Bounding Sphere, Cont'd § Certain types of objects are poorly represented by bounding spheres and have a lot of false positives. Bounding spheres for different objects

Axis-Aligned Bounding Box § § § In 2 D, an AABB has every side parallel to a coordinate axis. In 3 D, every side of 3 D prism is parallel to a coordinate plane. Represented by a min and max point (in 2 D this corresponds to bottom left and top right): class AABB 2 D Vector 2 min Vector 2 max end § Still fairly efficient for calculations.

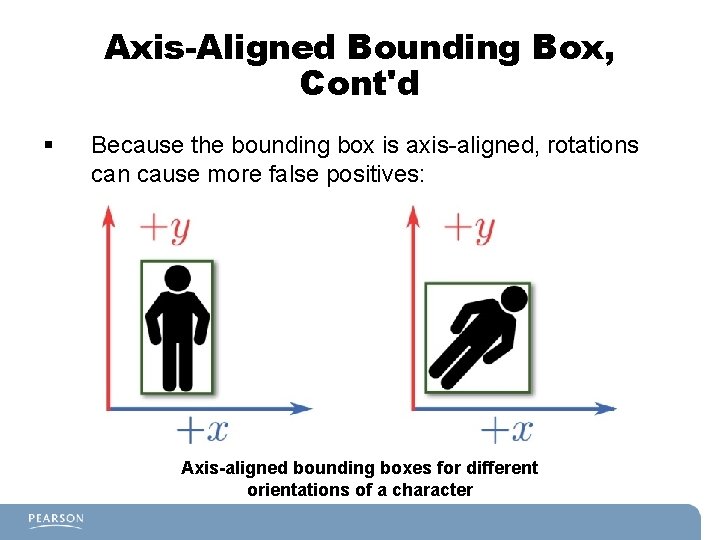

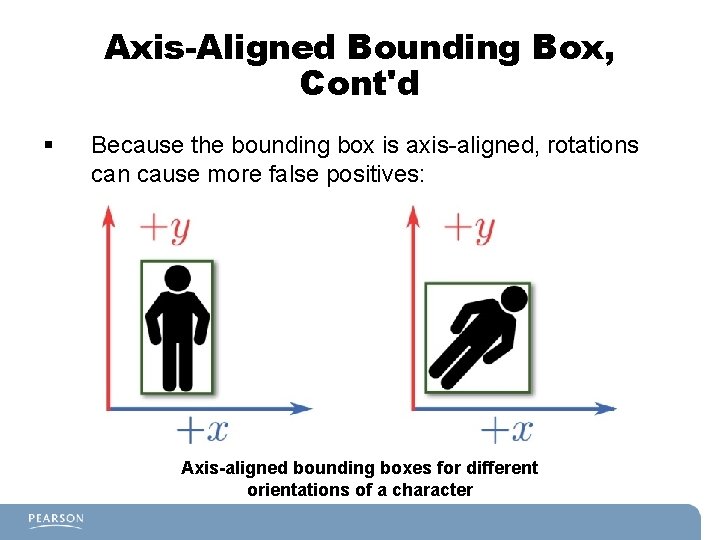

Axis-Aligned Bounding Box, Cont'd § Because the bounding box is axis-aligned, rotations can cause more false positives: Axis-aligned bounding boxes for different orientations of a character

Oriented Bounding Box § Like an AABB, but no axis restriction. § This means the OBB can rotate with no axis restriction. § Can be represented in different ways, but calculations are far more complex than an AABB.

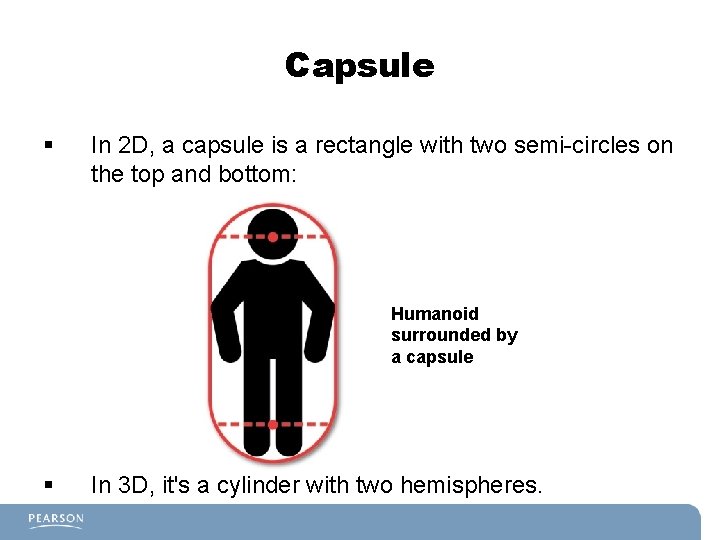

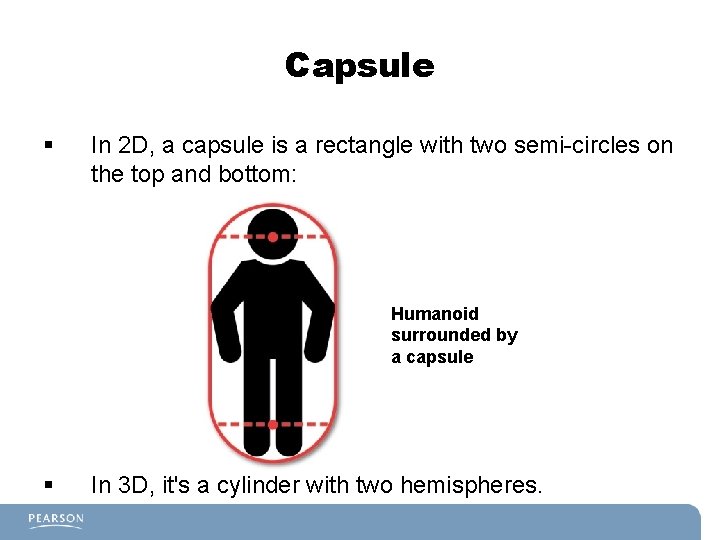

Capsule § In 2 D, a capsule is a rectangle with two semi-circles on the top and bottom: Humanoid surrounded by a capsule § In 3 D, it's a cylinder with two hemispheres.

Capsule, Cont'd § In code, we represent a capsule as a line segment with a radius: struct Capsule 2 D Vector 2 start. Point Vector 2 end. Point float radius end

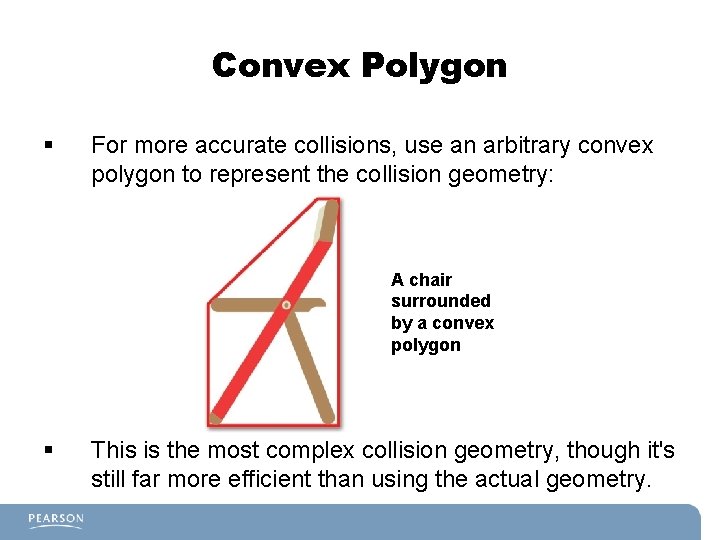

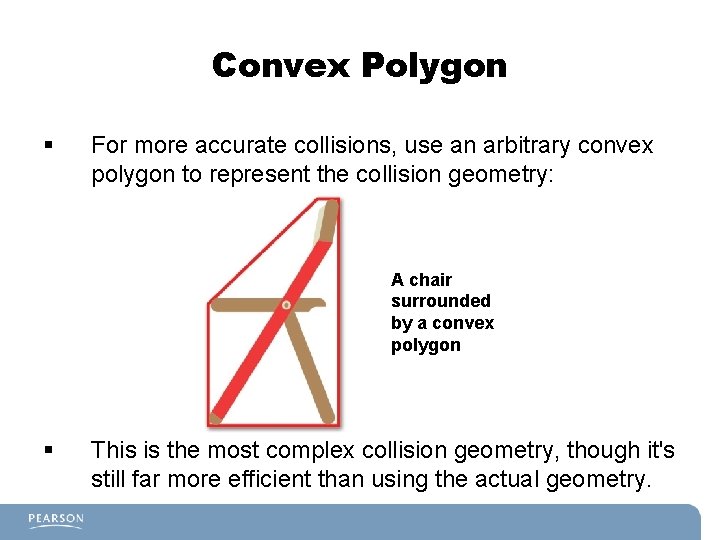

Convex Polygon § For more accurate collisions, use an arbitrary convex polygon to represent the collision geometry: A chair surrounded by a convex polygon § This is the most complex collision geometry, though it's still far more efficient than using the actual geometry.

Lists of Collision Geometries § § We also can represent an object as more than one collision geometry. For example, a human could have: – Sphere for head – AABB for torso – Convex polygons for arms/legs

Collision Detection § Using mathematical equations to calculate whether one type of collision geometry intersects with another. § Requires the use of linear algebra. § We won't cover all the possible collision permutations, but rather some of the most common ones.

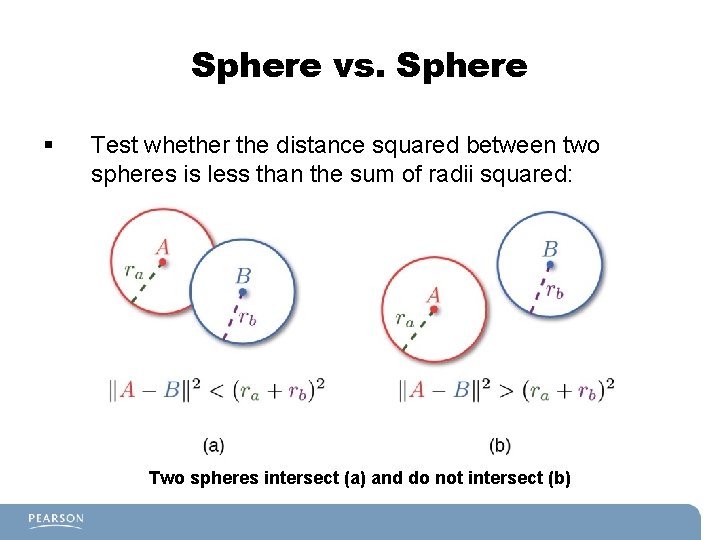

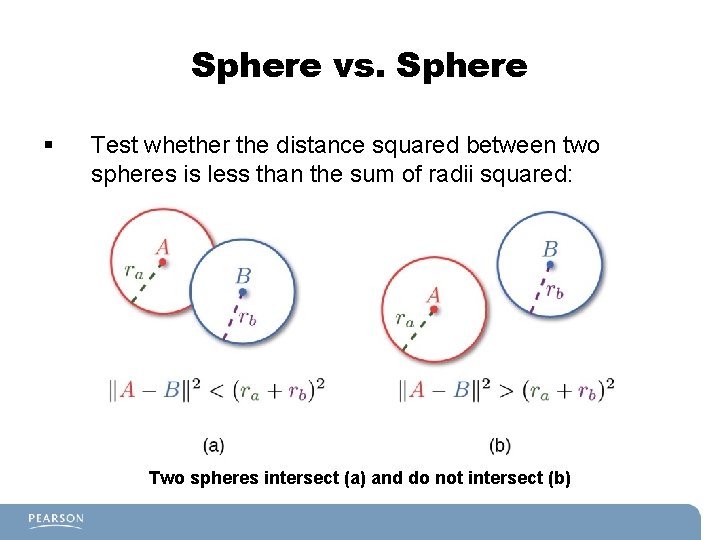

Sphere vs. Sphere § Test whether the distance squared between two spheres is less than the sum of radii squared: Two spheres intersect (a) and do not intersect (b)

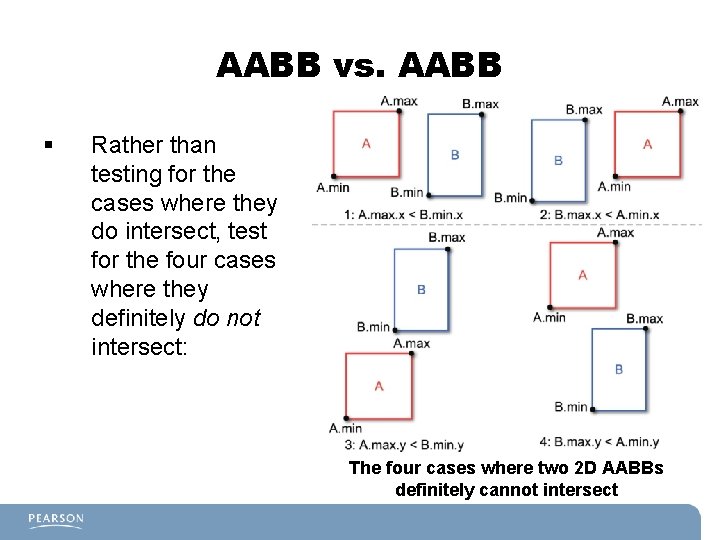

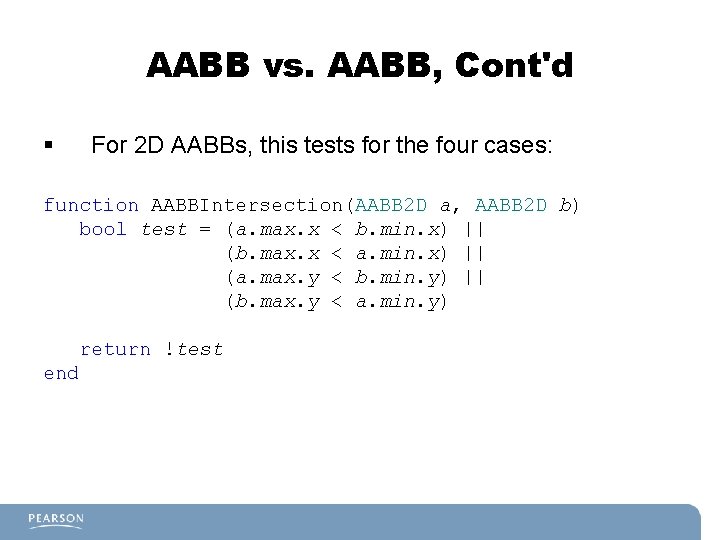

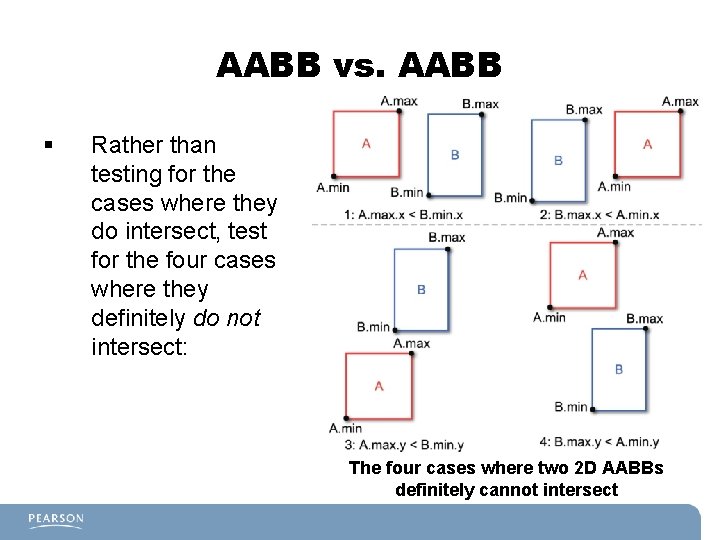

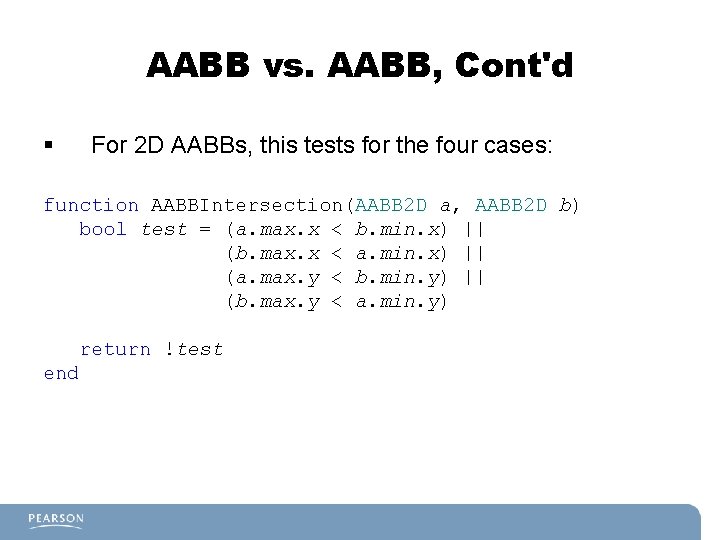

AABB vs. AABB § Rather than testing for the cases where they do intersect, test for the four cases where they definitely do not intersect: The four cases where two 2 D AABBs definitely cannot intersect

AABB vs. AABB, Cont'd § For 2 D AABBs, this tests for the four cases: function AABBIntersection(AABB 2 D a, AABB 2 D b) bool test = (a. max. x < b. min. x) || (b. max. x < a. min. x) || (a. max. y < b. min. y) || (b. max. y < a. min. y) return !test end

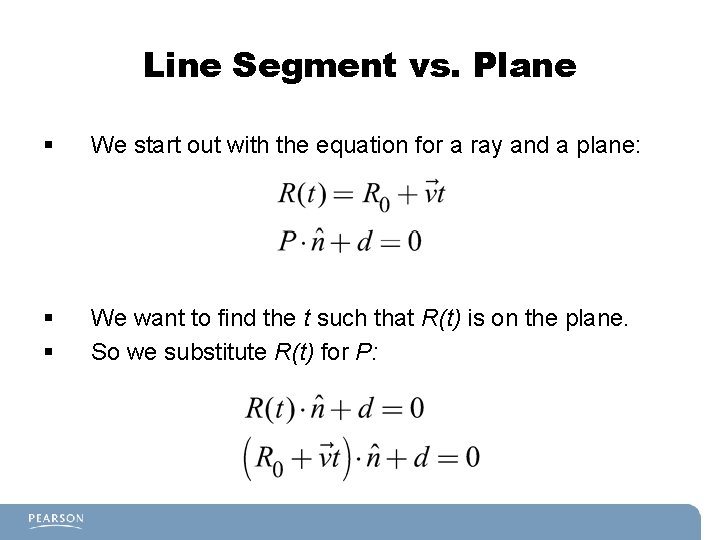

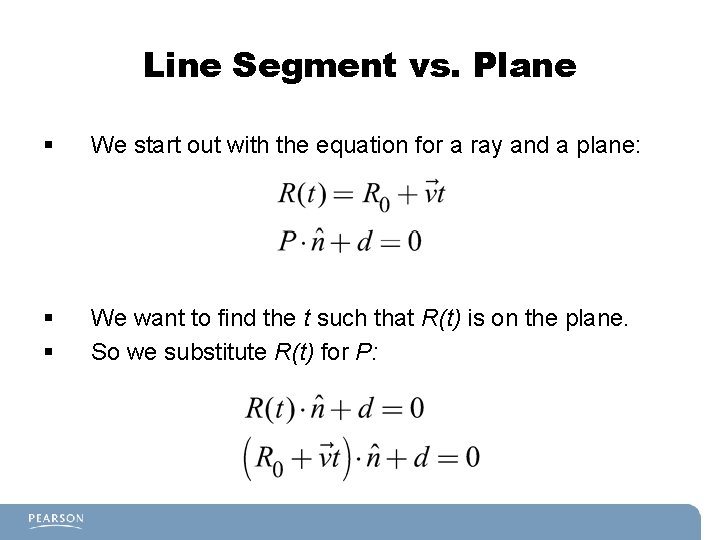

Line Segment vs. Plane § We start out with the equation for a ray and a plane: § § We want to find the t such that R(t) is on the plane. So we substitute R(t) for P:

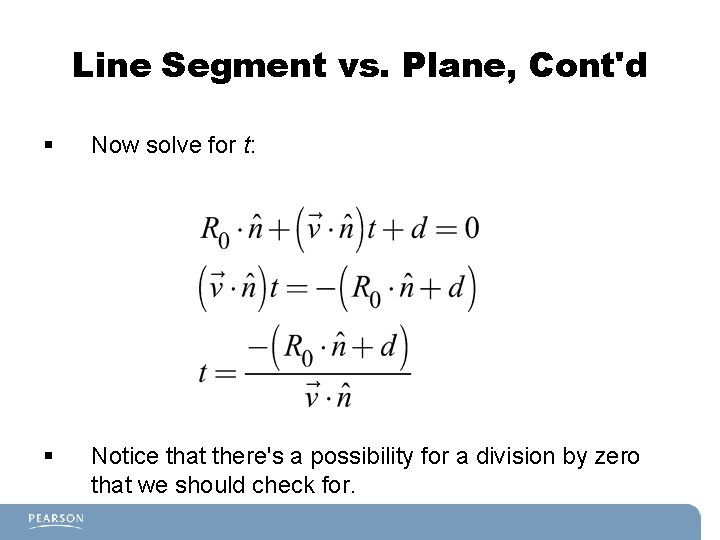

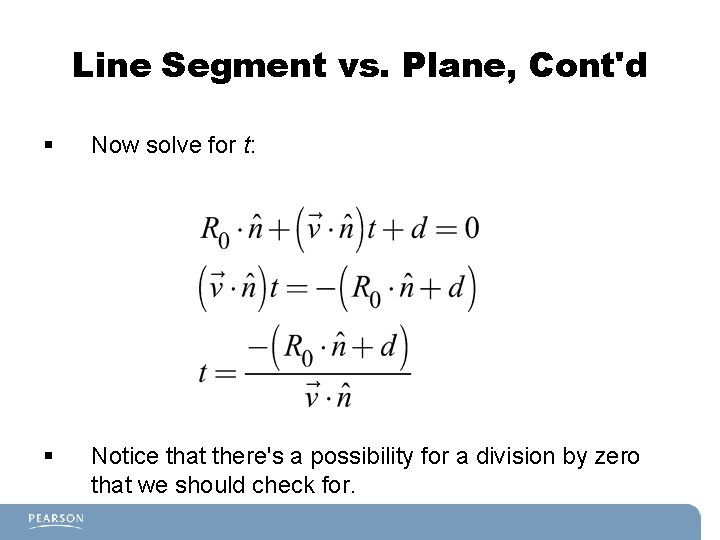

Line Segment vs. Plane, Cont'd § Now solve for t: § Notice that there's a possibility for a division by zero that we should check for.

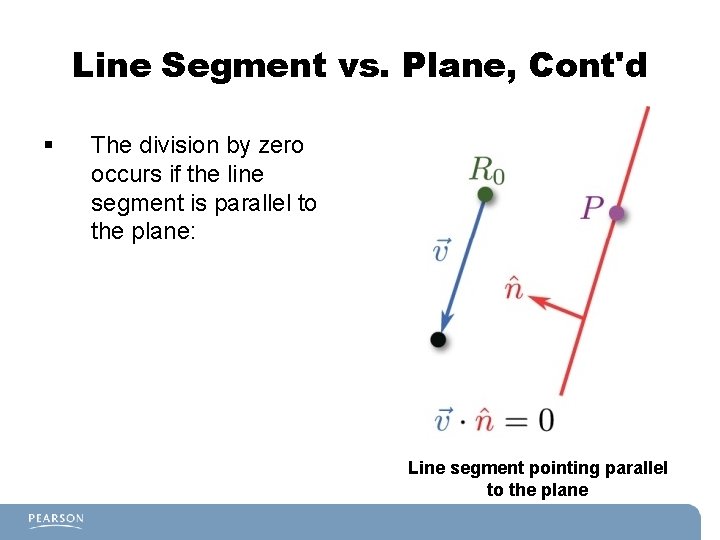

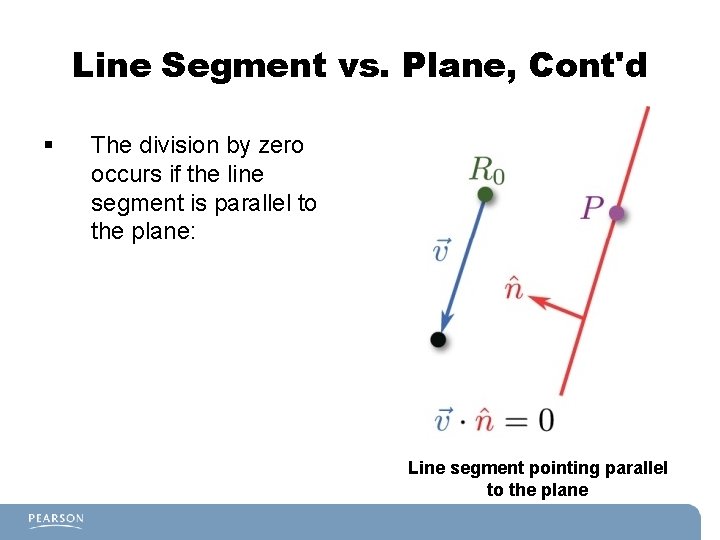

Line Segment vs. Plane, Cont'd § The division by zero occurs if the line segment is parallel to the plane: Line segment pointing parallel to the plane

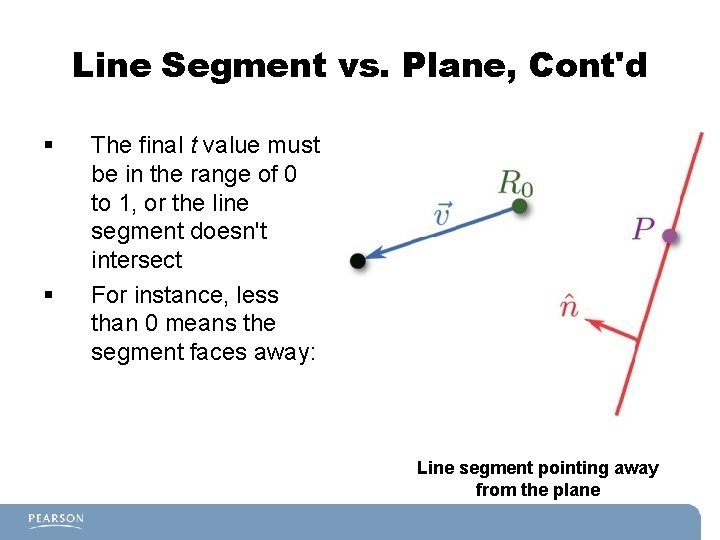

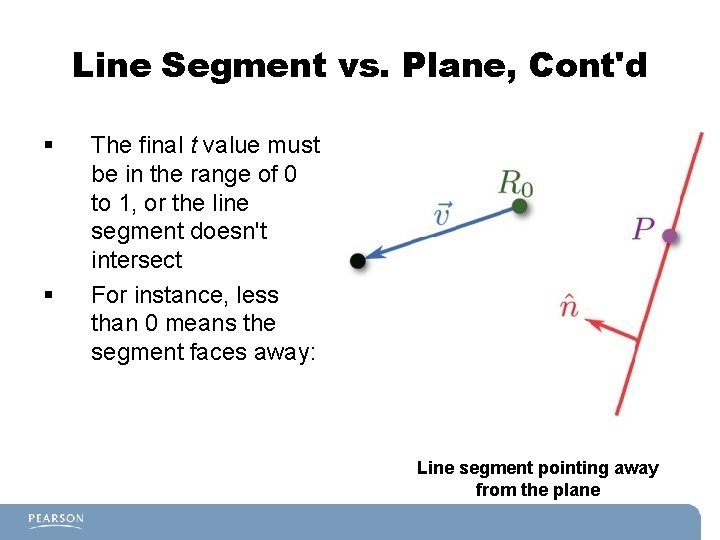

Line Segment vs. Plane, Cont'd § § The final t value must be in the range of 0 to 1, or the line segment doesn't intersect For instance, less than 0 means the segment faces away: Line segment pointing away from the plane

Line Segment vs. Triangle § First, construct the plane that the triangle is on, and test for line segment vs. plane intersection. § If a point of intersection between the segment and plane exists, we need to then test whether it's inside or outside the triangle. § The way to test this is to see whether it's inside each side of the triangle.

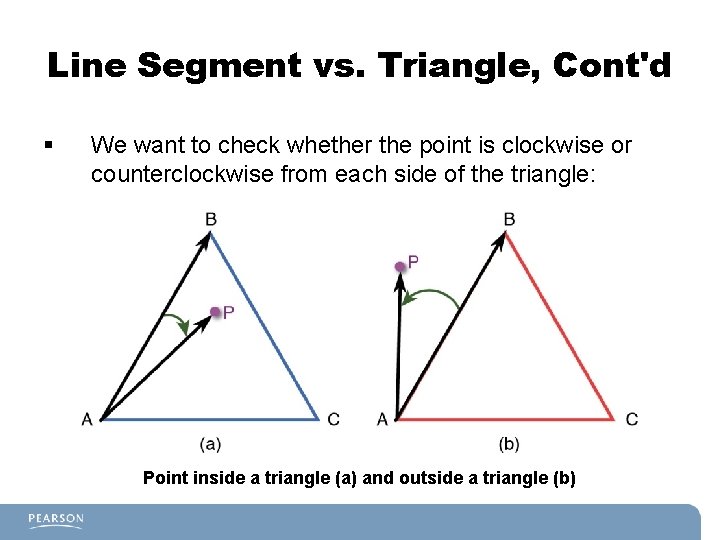

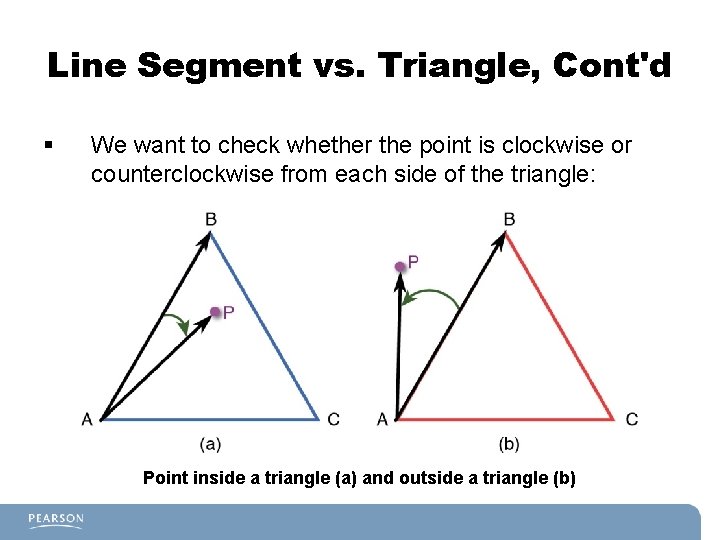

Line Segment vs. Triangle, Cont'd § We want to check whether the point is clockwise or counterclockwise from each side of the triangle: Point inside a triangle (a) and outside a triangle (b)

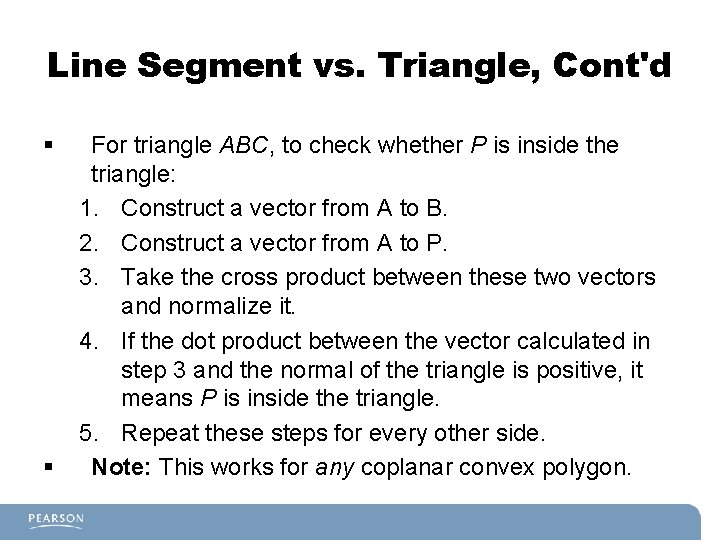

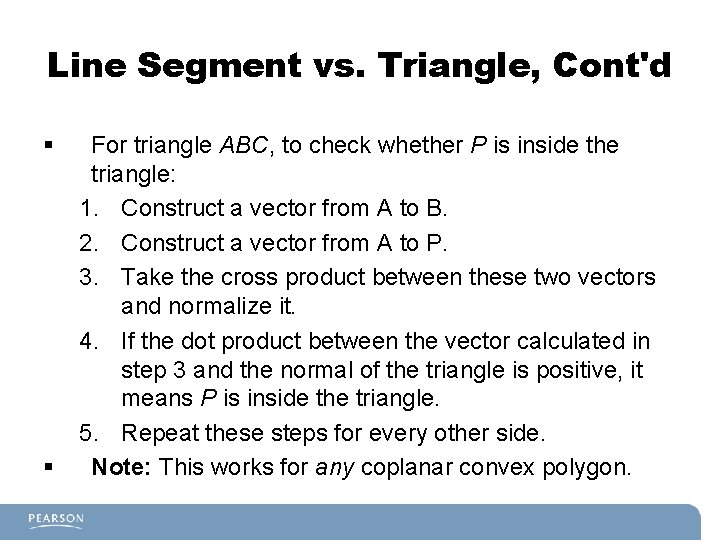

Line Segment vs. Triangle, Cont'd § § For triangle ABC, to check whether P is inside the triangle: 1. Construct a vector from A to B. 2. Construct a vector from A to P. 3. Take the cross product between these two vectors and normalize it. 4. If the dot product between the vector calculated in step 3 and the normal of the triangle is positive, it means P is inside the triangle. 5. Repeat these steps for every other side. Note: This works for any coplanar convex polygon.

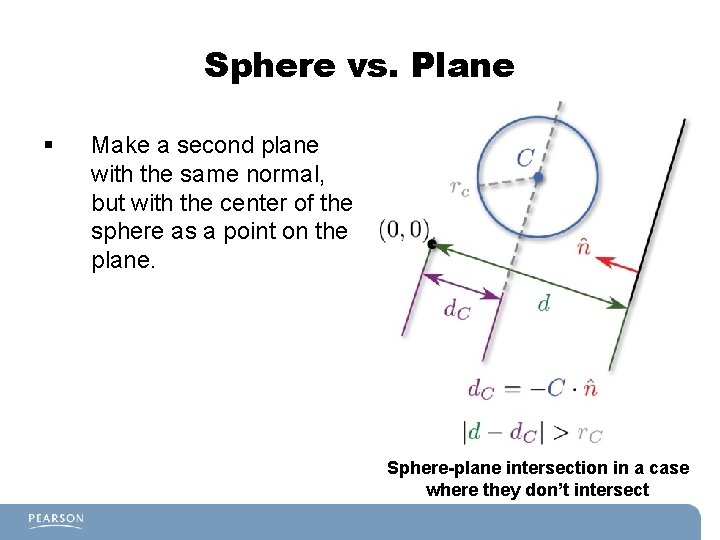

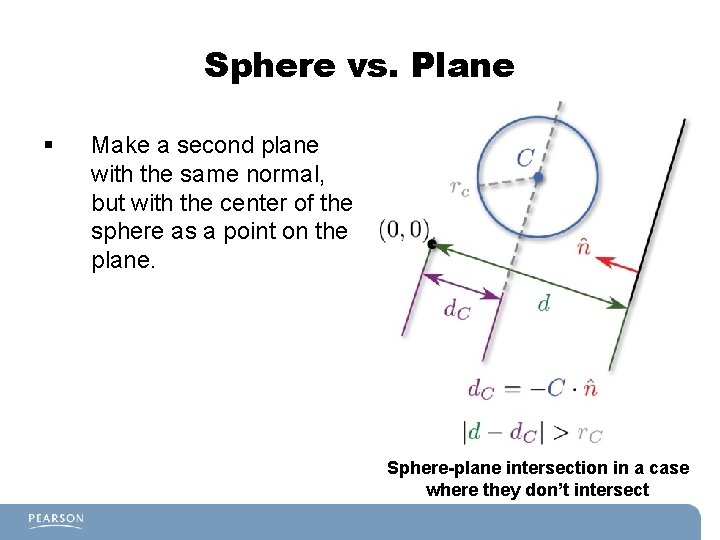

Sphere vs. Plane § Make a second plane with the same normal, but with the center of the sphere as a point on the plane. Sphere-plane intersection in a case where they don’t intersect

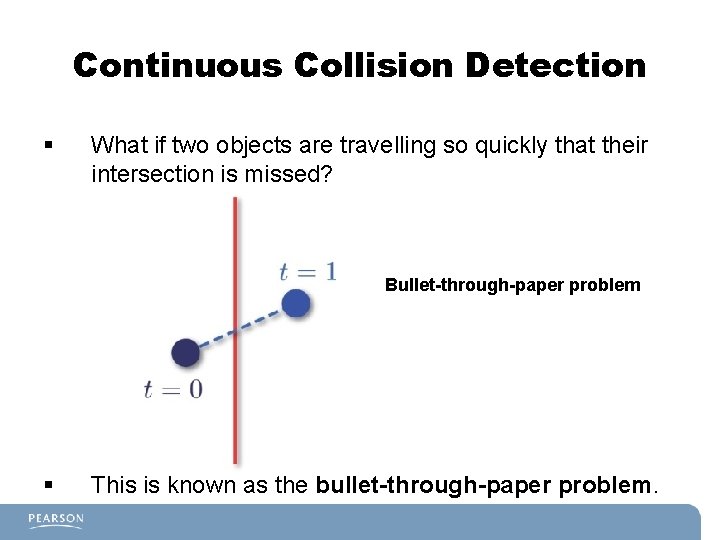

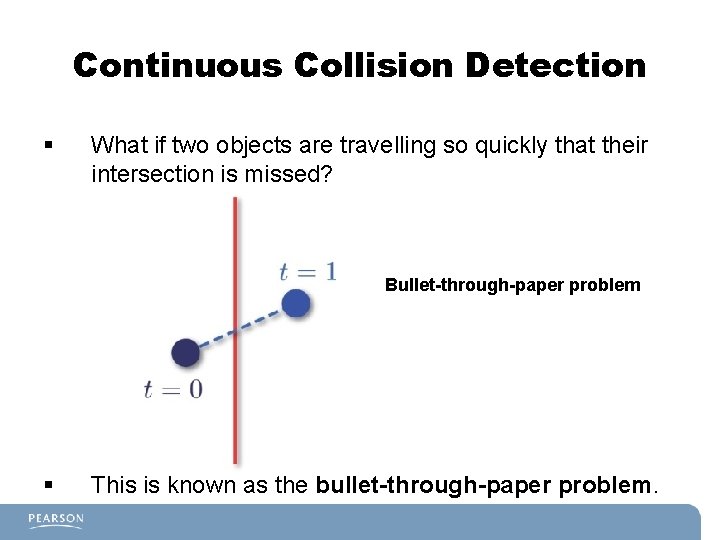

Continuous Collision Detection § What if two objects are travelling so quickly that their intersection is missed? Bullet-through-paper problem § This is known as the bullet-through-paper problem.

Continuous Collision Detection, Cont'd § We can use continuous collision detection to figure out whether two objects collided in between frames. § One such collision is two moving spheres, known as swept spheres. § Swept spheres, it turns out, are actually capsules.

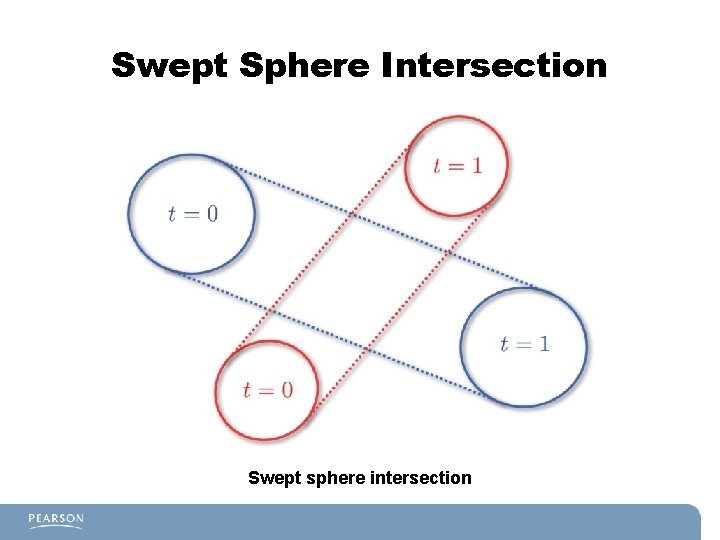

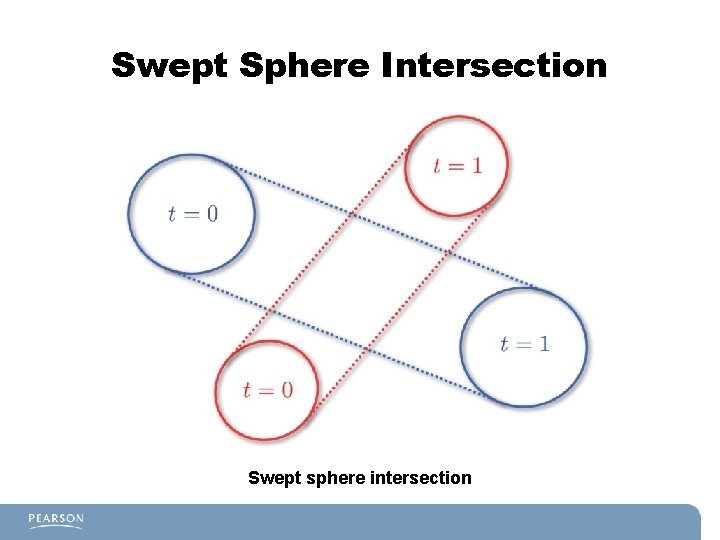

Swept Sphere Intersection Swept sphere intersection

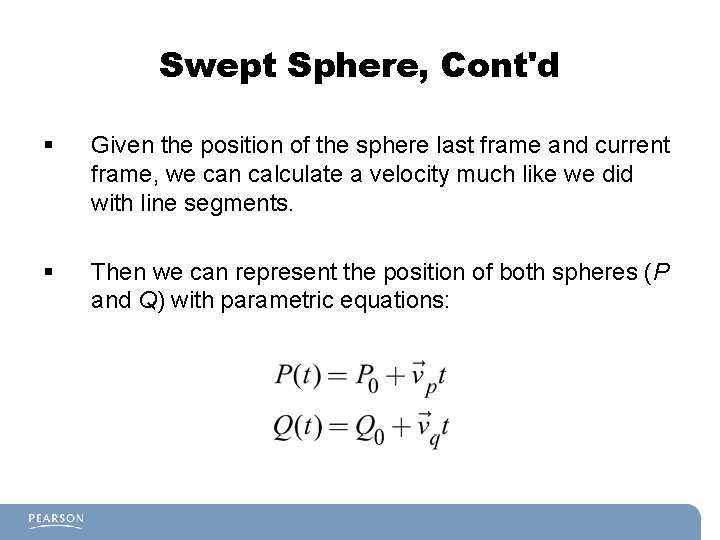

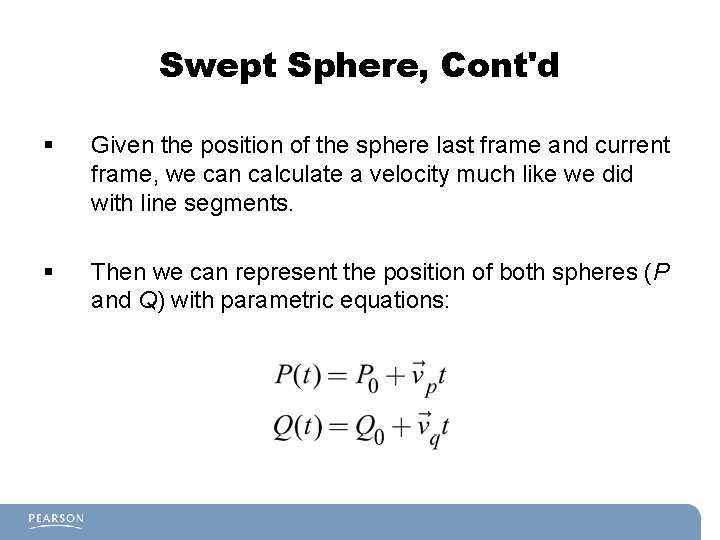

Swept Sphere, Cont'd § Given the position of the sphere last frame and current frame, we can calculate a velocity much like we did with line segments. § Then we can represent the position of both spheres (P and Q) with parametric equations:

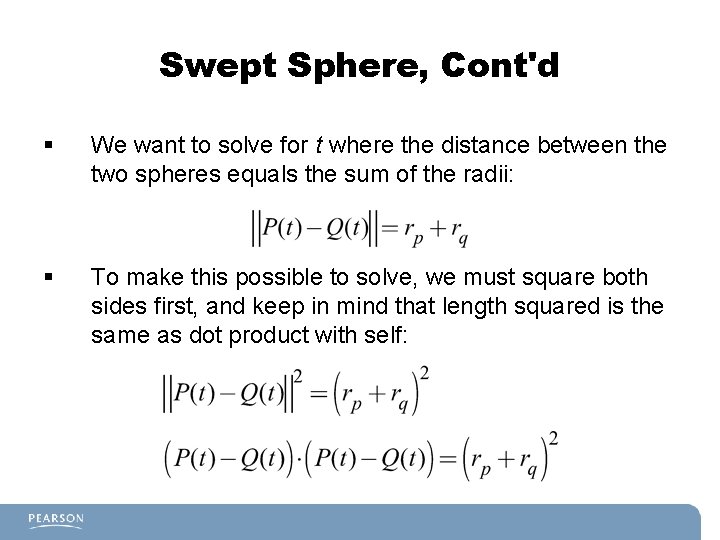

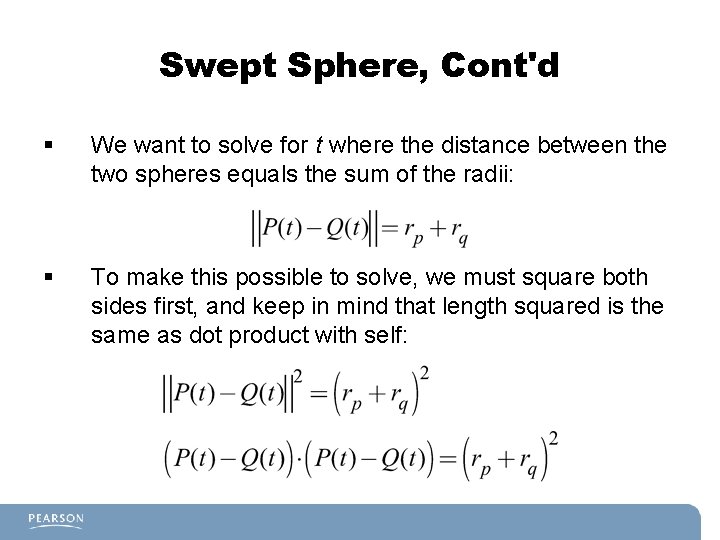

Swept Sphere, Cont'd § We want to solve for t where the distance between the two spheres equals the sum of the radii: § To make this possible to solve, we must square both sides first, and keep in mind that length squared is the same as dot product with self:

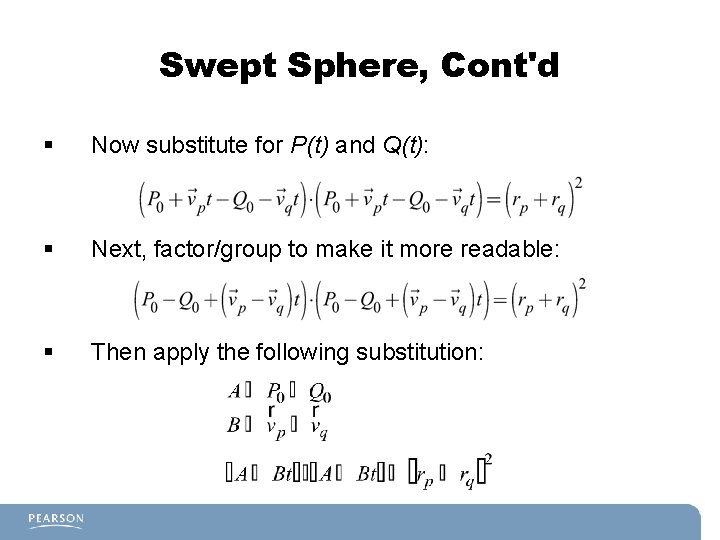

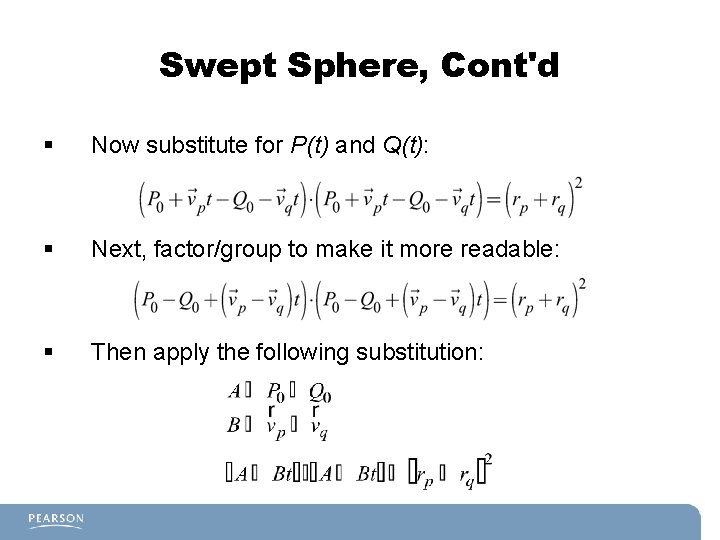

Swept Sphere, Cont'd § Now substitute for P(t) and Q(t): § Next, factor/group to make it more readable: § Then apply the following substitution:

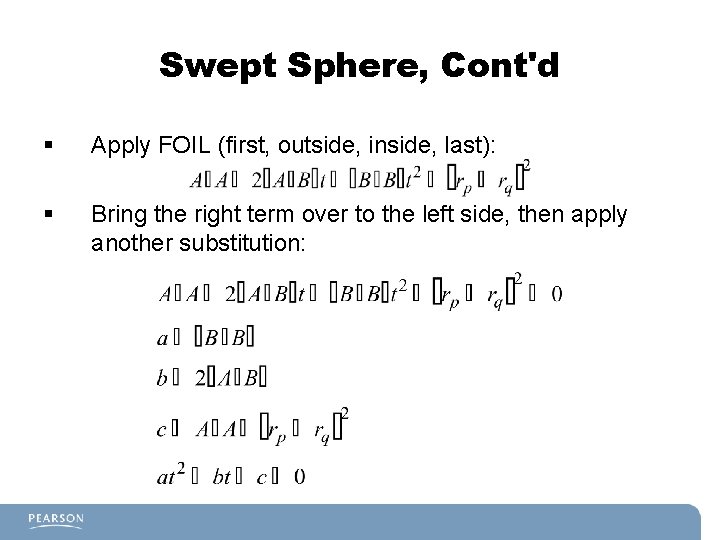

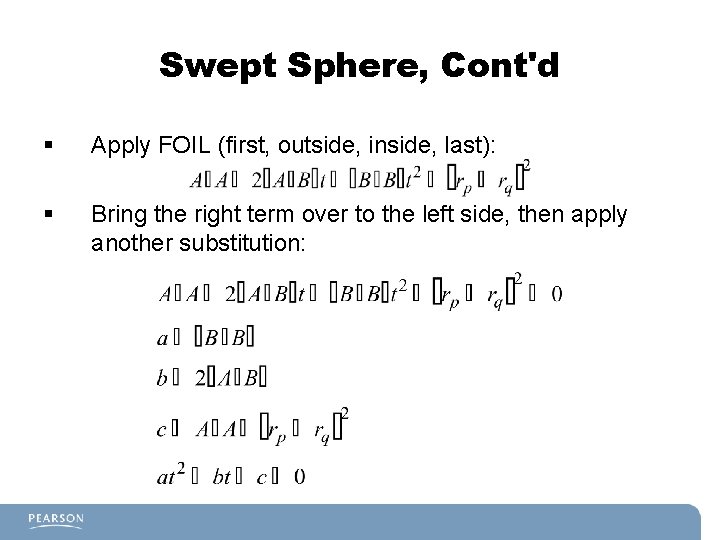

Swept Sphere, Cont'd § Apply FOIL (first, outside, inside, last): § Bring the right term over to the left side, then apply another substitution:

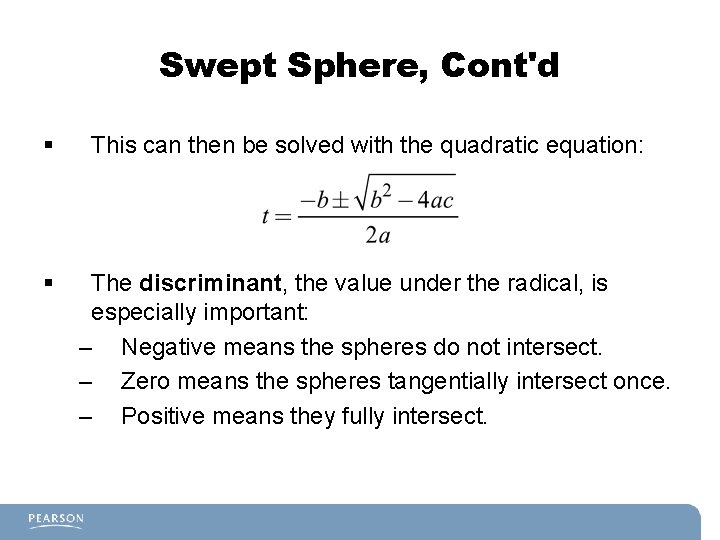

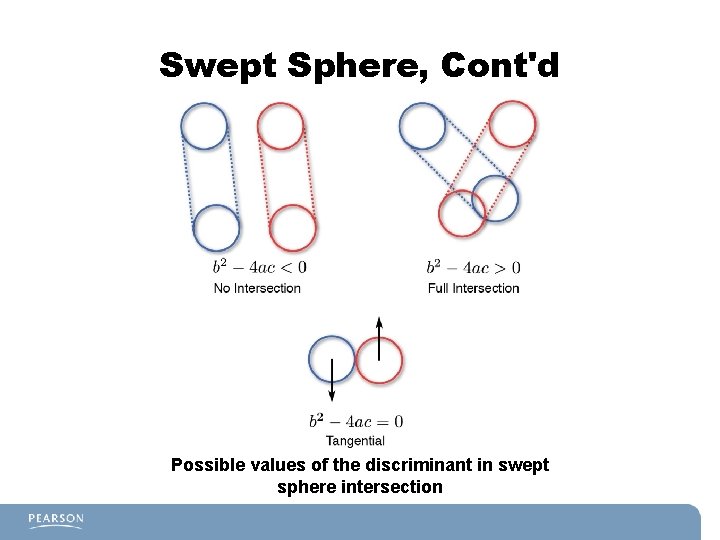

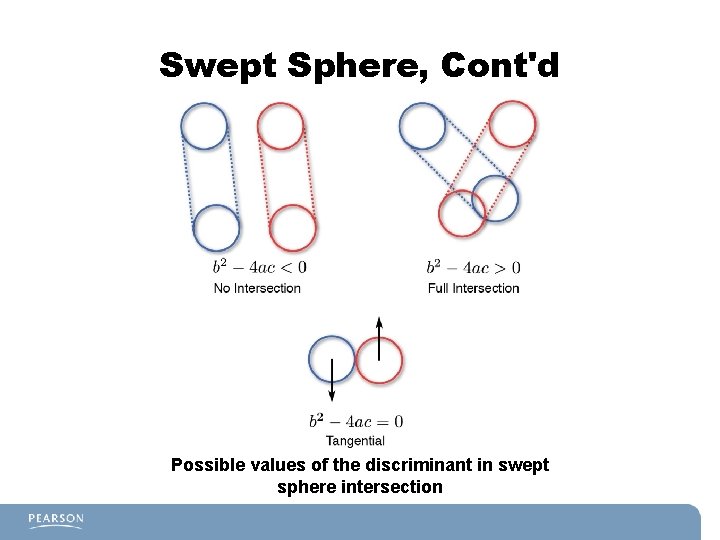

Swept Sphere, Cont'd § § This can then be solved with the quadratic equation: The discriminant, the value under the radical, is especially important: – Negative means the spheres do not intersect. – Zero means the spheres tangentially intersect once. – Positive means they fully intersect.

Swept Sphere, Cont'd Possible values of the discriminant in swept sphere intersection

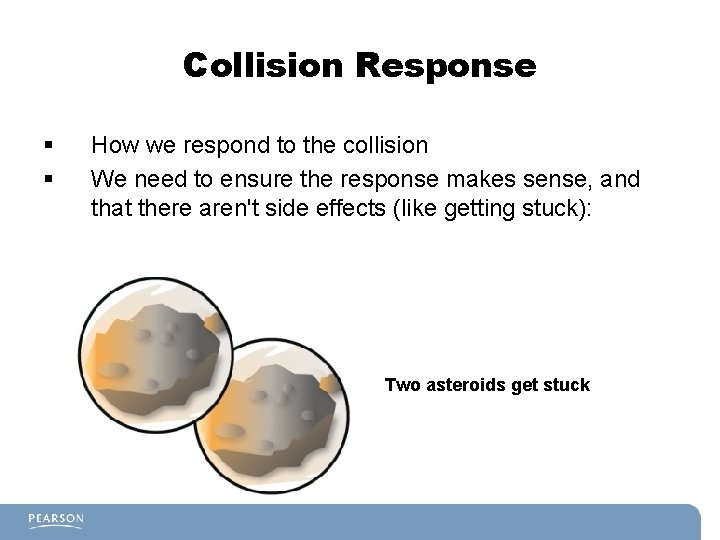

Collision Response § § How we respond to the collision We need to ensure the response makes sense, and that there aren't side effects (like getting stuck): Two asteroids get stuck

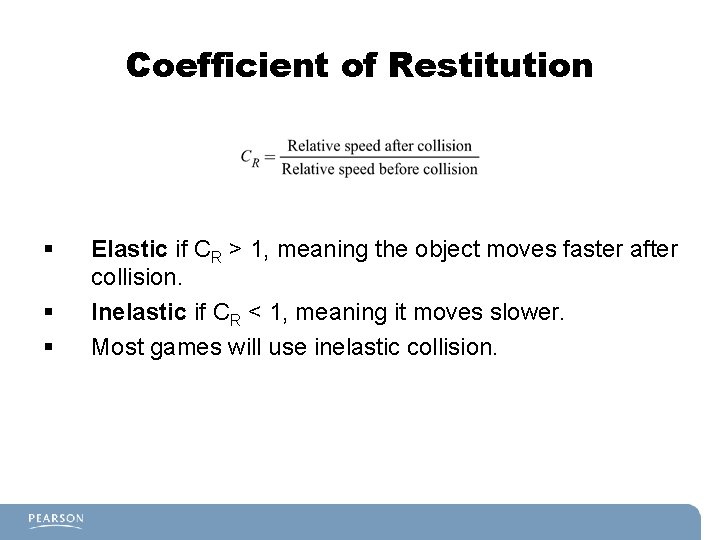

Coefficient of Restitution § § § Elastic if CR > 1, meaning the object moves faster after collision. Inelastic if CR < 1, meaning it moves slower. Most games will use inelastic collision.

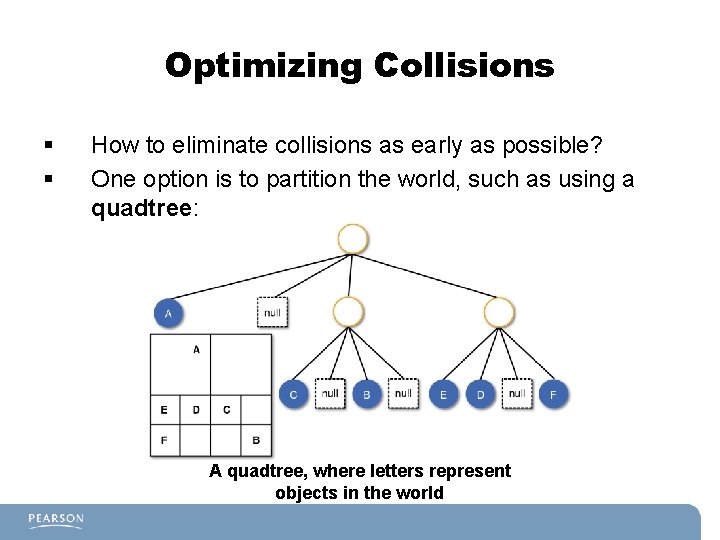

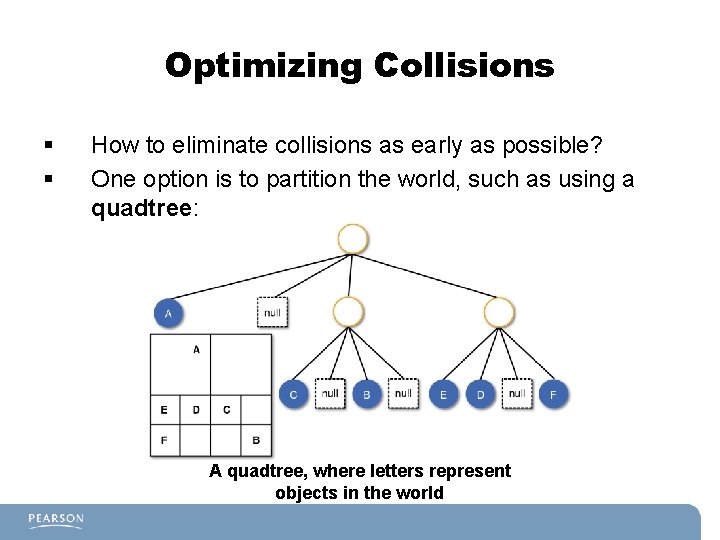

Optimizing Collisions § § How to eliminate collisions as early as possible? One option is to partition the world, such as using a quadtree: A quadtree, where letters represent objects in the world

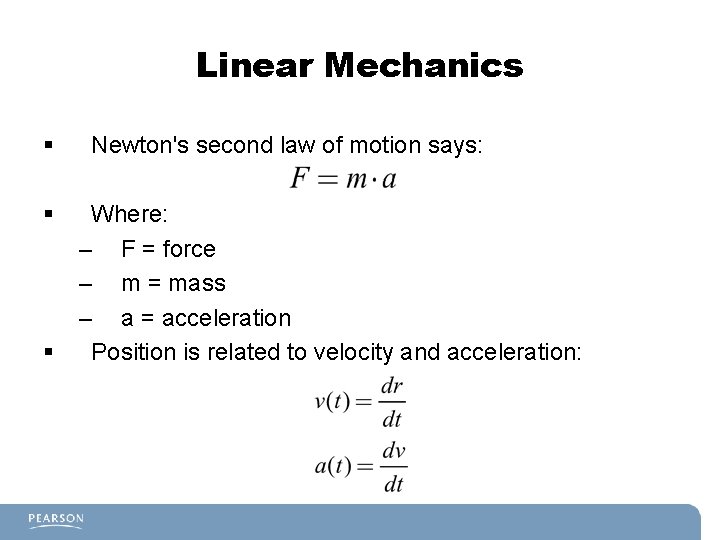

Linear Mechanics § § § Newton's second law of motion says: Where: – F = force – m = mass – a = acceleration Position is related to velocity and acceleration:

Linear Mechanics for Games § We can apply forces to objects with a mass. § Given the position and velocity last frame, based on these new forces, determine the position and velocity this frame. § To do this, we need to use numeric integration. § But first, a word on time steps…

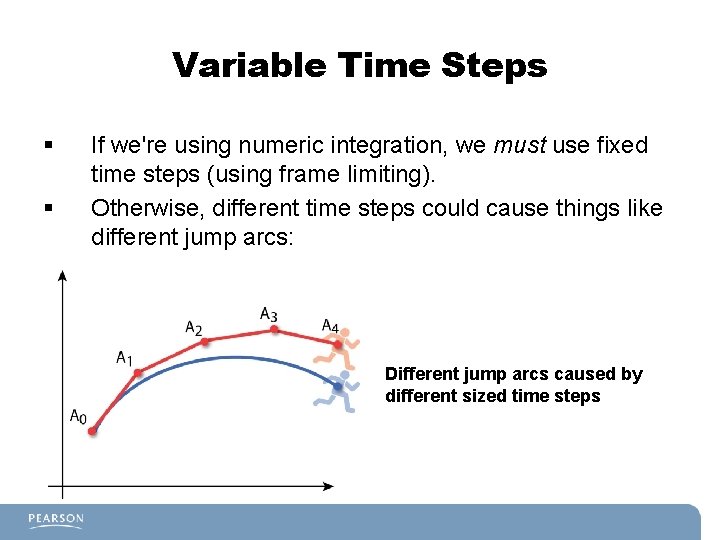

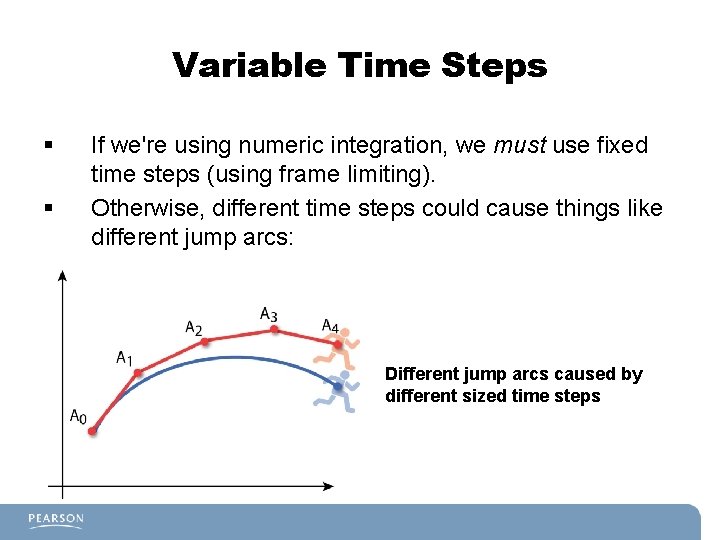

Variable Time Steps § § If we're using numeric integration, we must use fixed time steps (using frame limiting). Otherwise, different time steps could cause things like different jump arcs: Different jump arcs caused by different sized time steps

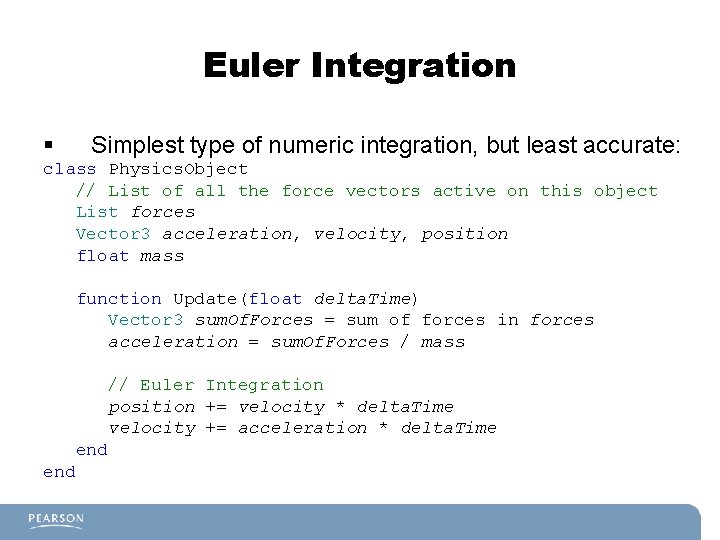

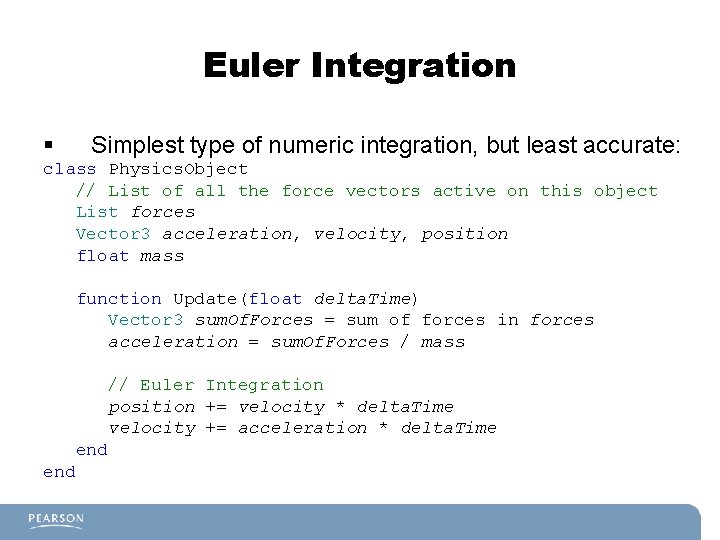

Euler Integration § Simplest type of numeric integration, but least accurate: class Physics. Object // List of all the force vectors active on this object List forces Vector 3 acceleration, velocity, position float mass function Update(float delta. Time) Vector 3 sum. Of. Forces = sum of forces in forces acceleration = sum. Of. Forces / mass // Euler Integration position += velocity * delta. Time velocity += acceleration * delta. Time end

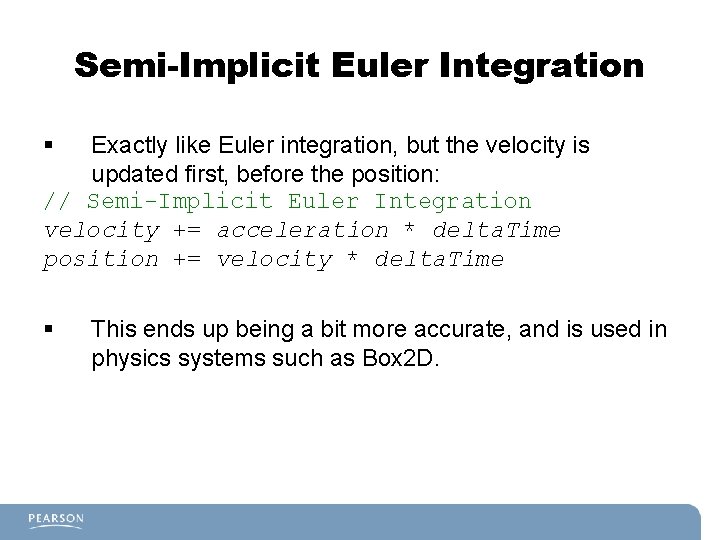

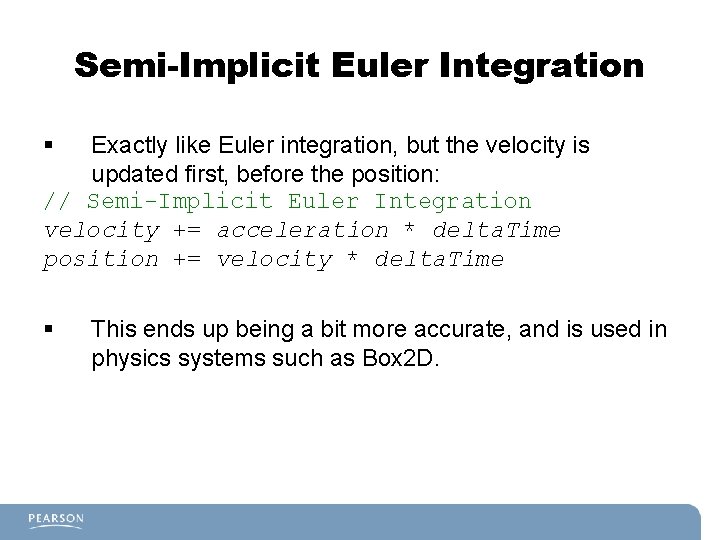

Semi-Implicit Euler Integration § Exactly like Euler integration, but the velocity is updated first, before the position: // Semi-Implicit Euler Integration velocity += acceleration * delta. Time position += velocity * delta. Time § This ends up being a bit more accurate, and is used in physics systems such as Box 2 D.

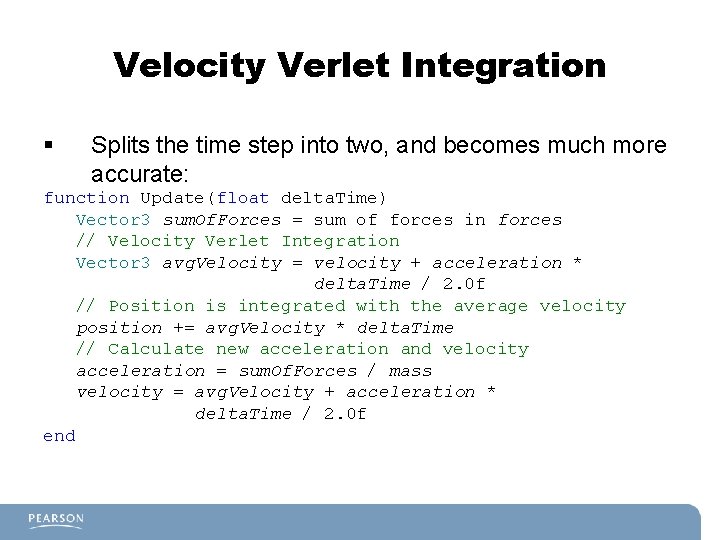

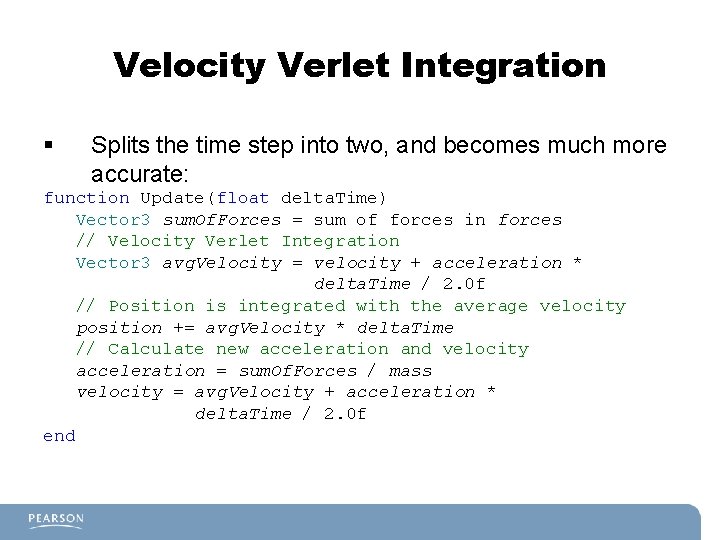

Velocity Verlet Integration § Splits the time step into two, and becomes much more accurate: function Update(float delta. Time) Vector 3 sum. Of. Forces = sum of forces in forces // Velocity Verlet Integration Vector 3 avg. Velocity = velocity + acceleration * delta. Time / 2. 0 f // Position is integrated with the average velocity position += avg. Velocity * delta. Time // Calculate new acceleration and velocity acceleration = sum. Of. Forces / mass velocity = avg. Velocity + acceleration * delta. Time / 2. 0 f end

Physics Middleware § § § Third-party libraries that implement all the core aspects of physics, including collision detection/response and movement. 3 D: – Havok—Industry standard, used by lots of major games – Phys. X—Also a popular solution, default physics system in Unreal 3 2 D: – Box 2 D—Most popular 2 D system, ported to many platforms