Fundamentals of Radiation Partial Periodic Table The Periodic

Fundamentals of Radiation

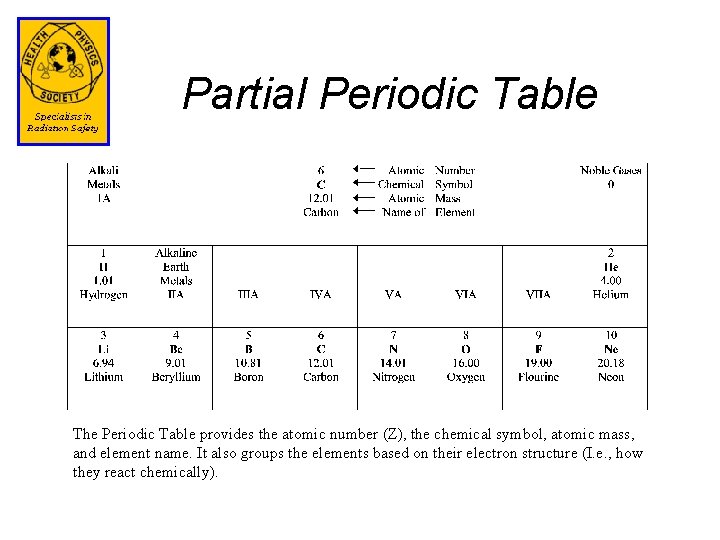

Partial Periodic Table The Periodic Table provides the atomic number (Z), the chemical symbol, atomic mass, and element name. It also groups the elements based on their electron structure (I. e. , how they react chemically).

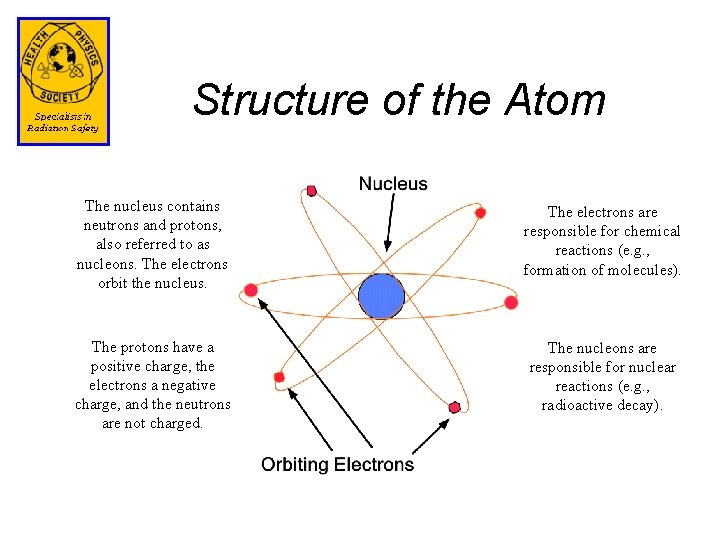

Structure of the Atom The nucleus contains neutrons and protons, also referred to as nucleons. The electrons orbit the nucleus. The electrons are responsible for chemical reactions (e. g. , formation of molecules). The protons have a positive charge, the electrons a negative charge, and the neutrons are not charged. The nucleons are responsible for nuclear reactions (e. g. , radioactive decay).

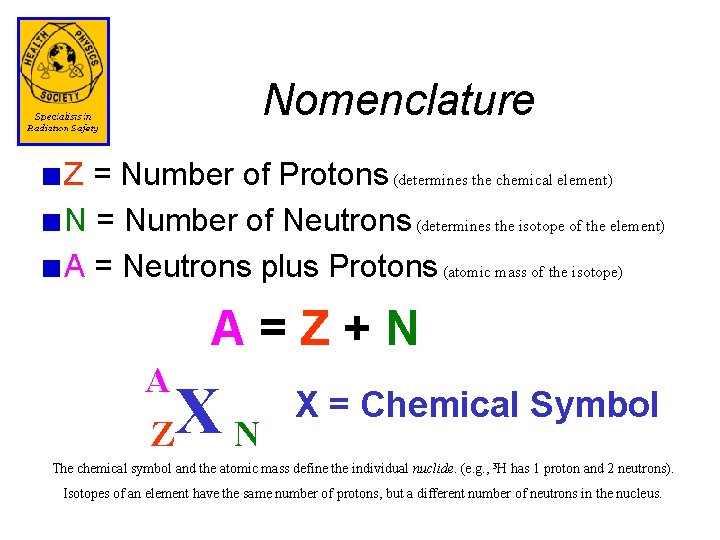

Nomenclature Z = Number of Protons (determines the chemical element) N = Number of Neutrons (determines the isotope of the element) A = Neutrons plus Protons (atomic mass of the isotope) A=Z+N A Z XN X = Chemical Symbol The chemical symbol and the atomic mass define the individual nuclide. (e. g. , 3 H has 1 proton and 2 neutrons). Isotopes of an element have the same number of protons, but a different number of neutrons in the nucleus.

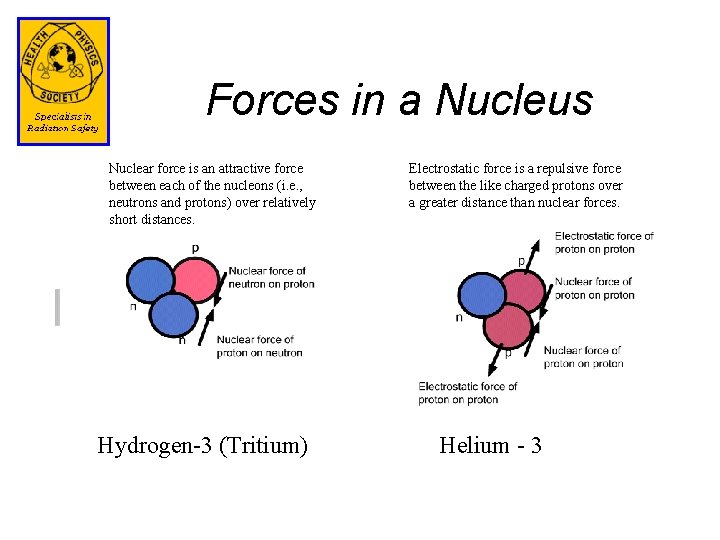

Forces in a Nucleus Nuclear force is an attractive force between each of the nucleons (i. e. , neutrons and protons) over relatively short distances. Hydrogen-3 (Tritium) Electrostatic force is a repulsive force between the like charged protons over a greater distance than nuclear forces. Helium - 3

Radioactive Decay The nuclides, as with most things in nature, want to be at their lowest energy state which is a stable nucleus. Radioactive decay occurs in nuclides where the nucleus is unstable. For stable nuclides with low atomic masses, the number of neutrons is equal to, or approximately equal to the number of protons (except for 1 H which only has one nucleon). As the atomic mass of the nuclide increases, the ratio of neutrons to protons must be greater than one for it to be stable, suggesting that more neutrons are required to provide nuclear forces to offset the electrostatic repulsive force between the increased number of protons. The nucleus may also become unstable when energy is added to it, placing it in an excited state. An example of this would be a free moving neutron inside of a reactor being captured by the nucleus of a 238 U nucleus. The nuclide reaches its stable state by undergoing radioactive decay.

Types of Radiation There are four types of radiation of interest: 1) Alpha ( ) which is a positively charged helium nucleus (2 protons and 2 neutrons). 2) Beta ( ) which is a negatively charged electron. 3) Gamma ( ) which is a packet of energy with zero rest mass. 4) Neutron (n) which is a released neutron. Mainly a concern during nuclear reactor operation.

Alpha Particle Helium-4 Nucleus Ø(2 neutrons, 2 protons) Slow moving, but high energy Cannot penetrate material easily ØStopped by one piece of paper ØStopped by dead layer of skin

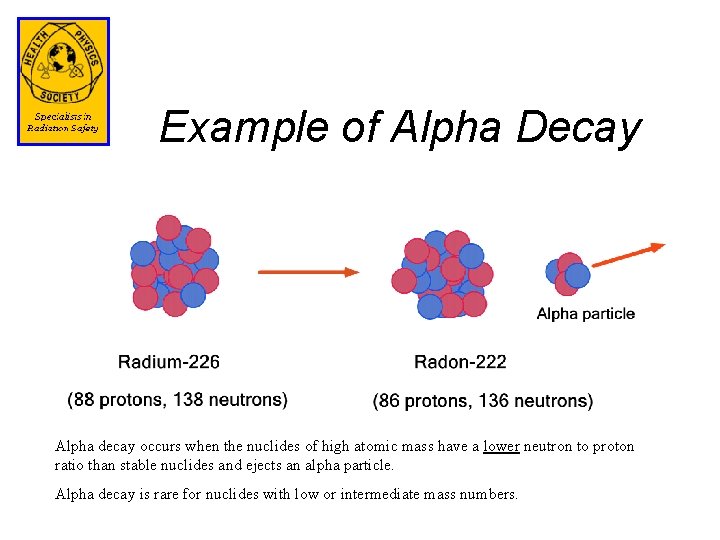

Example of Alpha Decay Alpha decay occurs when the nuclides of high atomic mass have a lower neutron to proton ratio than stable nuclides and ejects an alpha particle. Alpha decay is rare for nuclides with low or intermediate mass numbers.

Beta Particle Electron Fast moving, Medium energy Can penetrate material well ØStopped by 100 to 150 pieces of paper ØStopped by 0. 5 -1 centimeter of water

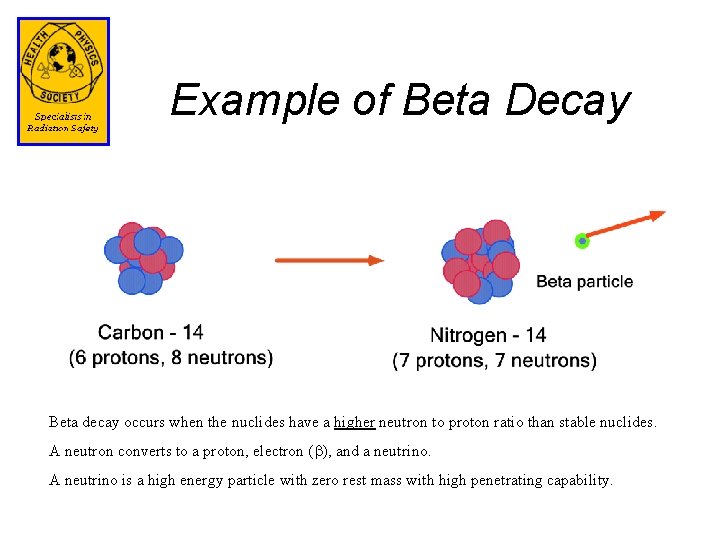

Example of Beta Decay Beta decay occurs when the nuclides have a higher neutron to proton ratio than stable nuclides. A neutron converts to a proton, electron ( ), and a neutrino. A neutrino is a high energy particle with zero rest mass with high penetrating capability.

Gamma Decay Electromagnetic radiation ØSimilar to light, x-rays, radio waves Emitted only by certain nuclei Speed of light; low to high energy Highly penetrating ØStop half of the s with about 1 cm of lead Øor 5 to 15 cm of water

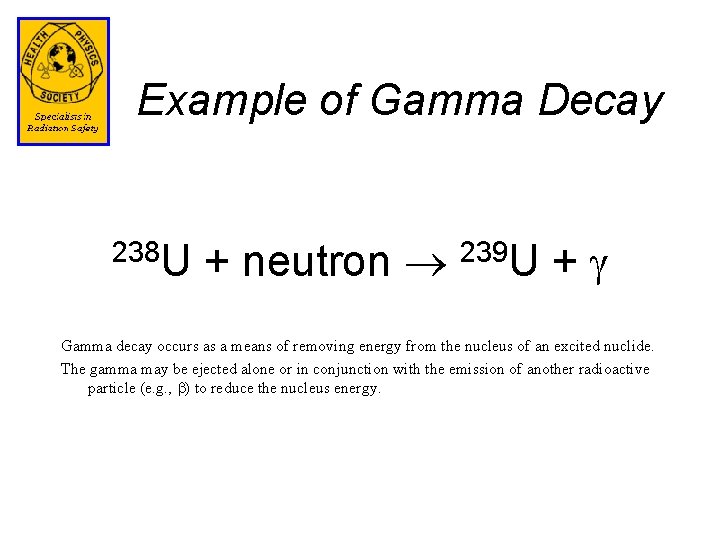

Example of Gamma Decay 238 U + neutron 239 U + Gamma decay occurs as a means of removing energy from the nucleus of an excited nuclide. The gamma may be ejected alone or in conjunction with the emission of another radioactive particle (e. g. , ) to reduce the nucleus energy.

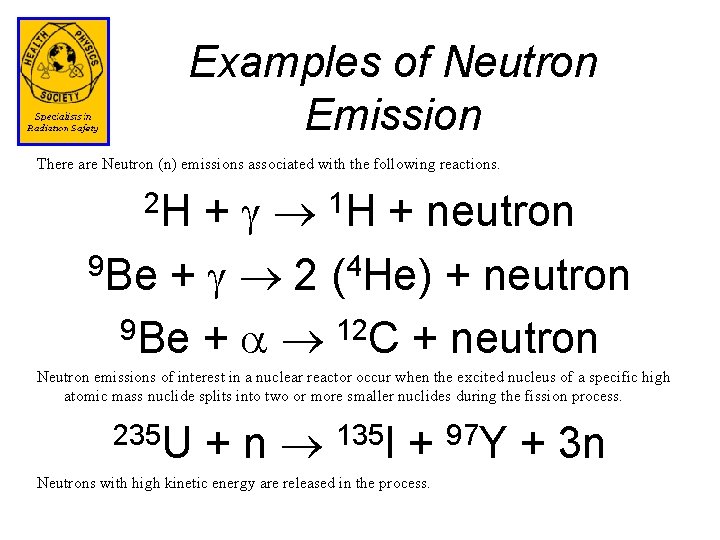

Examples of Neutron Emission There are Neutron (n) emissions associated with the following reactions. + 1 H + neutron 9 Be + 2 (4 He) + neutron 9 Be + 12 C + neutron 2 H Neutron emissions of interest in a nuclear reactor occur when the excited nucleus of a specific high atomic mass nuclide splits into two or more smaller nuclides during the fission process. 235 U + n 135 I + 97 Y + 3 n Neutrons with high kinetic energy are released in the process.

Half-life Each radioactive nucleus has a certain probability of decay per time Some decay quickly (fractions of a second), some later (thousands of years) Rate of decay depends on the number of nuclei available As number decreases, rate of decay decreases

Half-life In theory, all the radioactive material will never totally decay Define Half-life ØTime for half of the sample to decay

Half-life

Example Half-lives - Natural Uranium-238 (In soil) Ø 4. 5 Billion years Potassium-40 (in soil and body) Ø 1. 3 Billion years Carbon-14 (In all living tissue) Ø 5730 years Hydrogen-3 (in all water) Ø 12 years

Example Half-lives - Natural Radium-226 (In soil - produces radon) Ø 1600 years Radon-222 (in soil and air) Ø 3. 8 days Polonium-214 (radon progeny that decays in lungs) Ø 164 microseconds (0. 000164 s)

Example Half-lives Medical Uses Iodine - 131 (Thyroid treatment) Ø 8 days Technetium-99 m (Nuclear medicine) Ø 6 hours Gold-198 (Tumor therapy) Ø 2. 7 days

Activity = Decays per time Units: Ø 1 Becquerel = 1 decay per second (dps) Ø 1 Curie = 37 Billion dps Ø 1 micro. Curie (m. Ci) = 37, 000 dps Ø 1 pico. Curie (p. Ci) = 0. 037 dps

Example Activities Regulations Typical maximum alpha emitting radionuclide allowed without a license (some exceptions) Ø 0. 1 m. Ci Typical maximum beta emitting radionuclide allowed without a license (some exceptions) Ø 10 m. Ci

Example Activities - Natural Radioactivity Uranium-238 in cup of soil (typical) Ø 0. 003 m. Ci = 3000 p. Ci Radon-222 in air Ø 0. 5 p. Ci per liter (outdoor air) Ø 1 to hundreds of p. Ci per liter (houses) Potassium-40 in human body Ø 0. 1 m. Ci

Radiation Dose = Energy absorbed per mass Units: ØRad ØGray (Gy) [1 Gy = 100 rad)

Radiation Dose Equivalent Different radiations do different amounts of biological damage Dose Equivalent = Dose X QF QF = Quality factor ØBetas, Gamma: QF = 1; Alpha: QF = 20 Units ØRem (1 mrem = 0. 001 rem) ØSievert (Sv) [1 Sv = 100 rem)]

Radiation Exposure Old unit of exposure ØAmount of radiation present in air ØOnly applicable for x-rays and gamma radiation Units: ØRoentgen (R) Ø 1 R exposure in air will produce about 1 rad dose in human tissue

Example Doses Natural annual background radiation Øcosmic: 27 mrem (0. 27 m. Sv) ØTerrestrial: 28 mrem (0. 28 m. Sv) ØInternal: 39 mrem (. 039 m. Sv) ü[total natural (excl. Radon): ~100 mrem] ØRadon-lungs: 2400 mrem (24 m. Sv) [effective whole body: 200 mrem] § Source: NCRP Report #93

Example Doses Medical Radiation (Effective Whole Body Dose Equivalent) ØChest X-ray: 8 mrem (0. 08 m. Sv) ØHead CT scan: 111 mrem (1. 11 m. Sv) ØBarium Enema: 406 mrem (4. 06 m. Sv) ØExtremity X-ray: 1 mrem (0. 01 m. Sv) § Source: NCRP Report 100

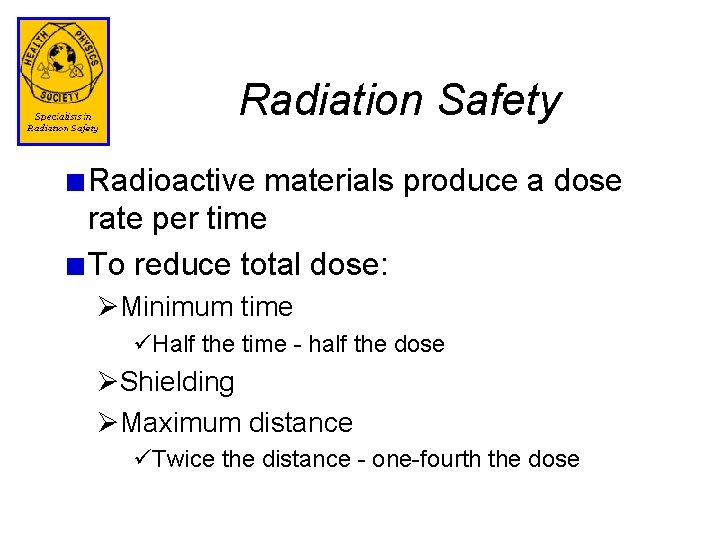

Radiation Safety Radioactive materials produce a dose rate per time To reduce total dose: ØMinimum time üHalf the time - half the dose ØShielding ØMaximum distance üTwice the distance - one-fourth the dose

- Slides: 29