Fuel Cell Waste Heat Recovery to Assist Thermoelectric

- Slides: 1

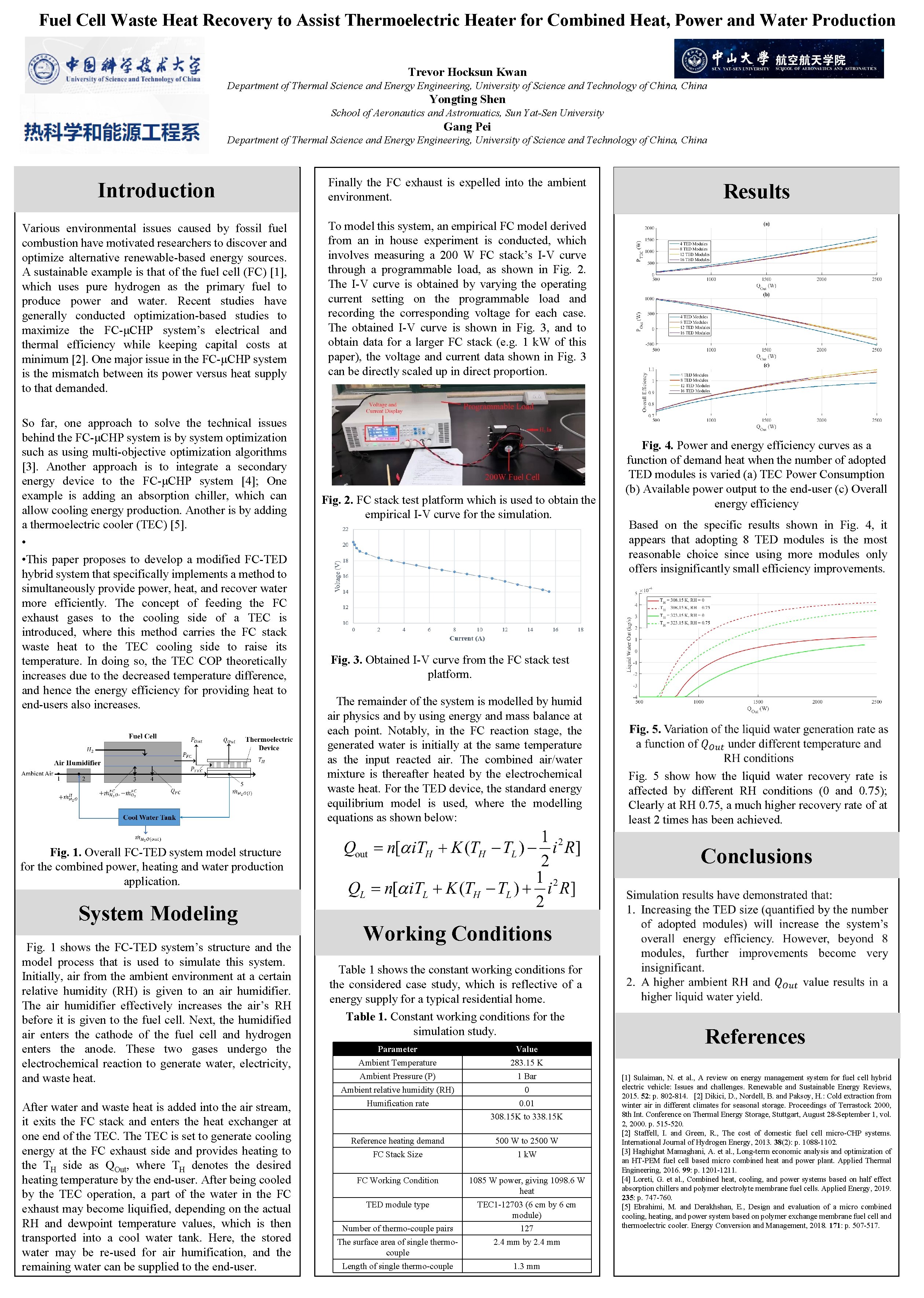

Fuel Cell Waste Heat Recovery to Assist Thermoelectric Heater for Combined Heat, Power and Water Production Trevor Hocksun Kwan Department of Thermal Science and Energy Engineering, University of Science and Technology of China, China Yongting Shen School of Aeronautics and Astronuatics, Sun Yat-Sen University Gang Pei Department of Thermal Science and Energy Engineering, University of Science and Technology of China, China Introduction Finally the FC exhaust is expelled into the ambient environment. Various environmental issues caused by fossil fuel combustion have motivated researchers to discover and optimize alternative renewable-based energy sources. A sustainable example is that of the fuel cell (FC) [1], which uses pure hydrogen as the primary fuel to produce power and water. Recent studies have generally conducted optimization-based studies to maximize the FC-μCHP system’s electrical and thermal efficiency while keeping capital costs at minimum [2]. One major issue in the FC-μCHP system is the mismatch between its power versus heat supply to that demanded. To model this system, an empirical FC model derived from an in house experiment is conducted, which involves measuring a 200 W FC stack’s I-V curve through a programmable load, as shown in Fig. 2. The I-V curve is obtained by varying the operating current setting on the programmable load and recording the corresponding voltage for each case. The obtained I-V curve is shown in Fig. 3, and to obtain data for a larger FC stack (e. g. 1 k. W of this paper), the voltage and current data shown in Fig. 3 can be directly scaled up in direct proportion. So far, one approach to solve the technical issues behind the FC-μCHP system is by system optimization such as using multi-objective optimization algorithms [3]. Another approach is to integrate a secondary energy device to the FC-μCHP system [4]; One example is adding an absorption chiller, which can allow cooling energy production. Another is by adding a thermoelectric cooler (TEC) [5]. • • This paper proposes to develop a modified FC-TED hybrid system that specifically implements a method to simultaneously provide power, heat, and recover water more efficiently. The concept of feeding the FC exhaust gases to the cooling side of a TEC is introduced, where this method carries the FC stack waste heat to the TEC cooling side to raise its temperature. In doing so, the TEC COP theoretically increases due to the decreased temperature difference, and hence the energy efficiency for providing heat to end-users also increases. Fig. 2. FC stack test platform which is used to obtain the empirical I-V curve for the simulation. Fig. 1 shows the FC-TED system’s structure and the model process that is used to simulate this system. Initially, air from the ambient environment at a certain relative humidity (RH) is given to an air humidifier. The air humidifier effectively increases the air’s RH before it is given to the fuel cell. Next, the humidified air enters the cathode of the fuel cell and hydrogen enters the anode. These two gases undergo the electrochemical reaction to generate water, electricity, and waste heat. After water and waste heat is added into the air stream, it exits the FC stack and enters the heat exchanger at one end of the TEC. The TEC is set to generate cooling energy at the FC exhaust side and provides heating to the TH side as QOut, where TH denotes the desired heating temperature by the end-user. After being cooled by the TEC operation, a part of the water in the FC exhaust may become liquified, depending on the actual RH and dewpoint temperature values, which is then transported into a cool water tank. Here, the stored water may be re-used for air humification, and the remaining water can be supplied to the end-user. Fig. 4. Power and energy efficiency curves as a function of demand heat when the number of adopted TED modules is varied (a) TEC Power Consumption (b) Available power output to the end-user (c) Overall energy efficiency Based on the specific results shown in Fig. 4, it appears that adopting 8 TED modules is the most reasonable choice since using more modules only offers insignificantly small efficiency improvements. Fig. 3. Obtained I-V curve from the FC stack test platform. The remainder of the system is modelled by humid air physics and by using energy and mass balance at each point. Notably, in the FC reaction stage, the generated water is initially at the same temperature as the input reacted air. The combined air/water mixture is thereafter heated by the electrochemical waste heat. For the TED device, the standard energy equilibrium model is used, where the modelling equations as shown below: Fig. 5 show the liquid water recovery rate is affected by different RH conditions (0 and 0. 75); Clearly at RH 0. 75, a much higher recovery rate of at least 2 times has been achieved. Conclusions Fig. 1. Overall FC-TED system model structure for the combined power, heating and water production application. System Modeling Results Working Conditions Table 1 shows the constant working conditions for the considered case study, which is reflective of a energy supply for a typical residential home. Table 1. Constant working conditions for the simulation study. Parameter Value Ambient Temperature 283. 15 K Ambient Pressure (P) 1 Bar Ambient relative humidity (RH) 0 Humification rate 0. 01 308. 15 K to 338. 15 K Reference heating demand 500 W to 2500 W FC Stack Size 1 k. W FC Working Condition 1085 W power, giving 1098. 6 W heat TED module type TEC 1 -12703 (6 cm by 6 cm module) Number of thermo-couple pairs 127 The surface area of single thermocouple 2. 4 mm by 2. 4 mm Length of single thermo-couple 1. 3 mm References [1] Sulaiman, N. et al. , A review on energy management system for fuel cell hybrid electric vehicle: Issues and challenges. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 2015. 52: p. 802 -814. [2] Dikici, D. , Nordell, B. and Paksoy, H. : Cold extraction from winter air in different climates for seasonal storage. Proceedings of Terrastock 2000, 8 th Int. Conference on Thermal Energy Storage, Stuttgart, August 28 -September 1, vol. 2, 2000. p. 515 -520. [2] Staffell, I. and Green, R. , The cost of domestic fuel cell micro-CHP systems. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy, 2013. 38(2): p. 1088 -1102. [3] Haghighat Mamaghani, A. et al. , Long-term economic analysis and optimization of an HT-PEM fuel cell based micro combined heat and power plant. Applied Thermal Engineering, 2016. 99: p. 1201 -1211. [4] Loreti, G. et al. , Combined heat, cooling, and power systems based on half effect absorption chillers and polymer electrolyte membrane fuel cells. Applied Energy, 2019. 235: p. 747 -760. [5] Ebrahimi, M. and Derakhshan, E. , Design and evaluation of a micro combined cooling, heating, and power system based on polymer exchange membrane fuel cell and thermoelectric cooler. Energy Conversion and Management, 2018. 171: p. 507 -517.