Foundations of Algorithms Fourth Edition Richard Neapolitan Kumarss

![T(n) = 2 T(n/2) + n = 2[ 2 T(n/22) + n/2] + n T(n) = 2 T(n/2) + n = 2[ 2 T(n/22) + n/2] + n](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h/8b62b33e94e2403735d34e2a4b5f0c07/image-8.jpg)

- Slides: 26

Foundations of Algorithms, Fourth Edition Richard Neapolitan, Kumarss Naimipour Chapter 2 Divide-and-Conquer

Divide and Conquer • In this approach a problem is divided into sub-problems and the same algorithm is applied to every subproblem ( often this is done recursively) • Examples – Binary Search (review algorithm in book) – Mergesort (review algorithm in book) – Quicksort

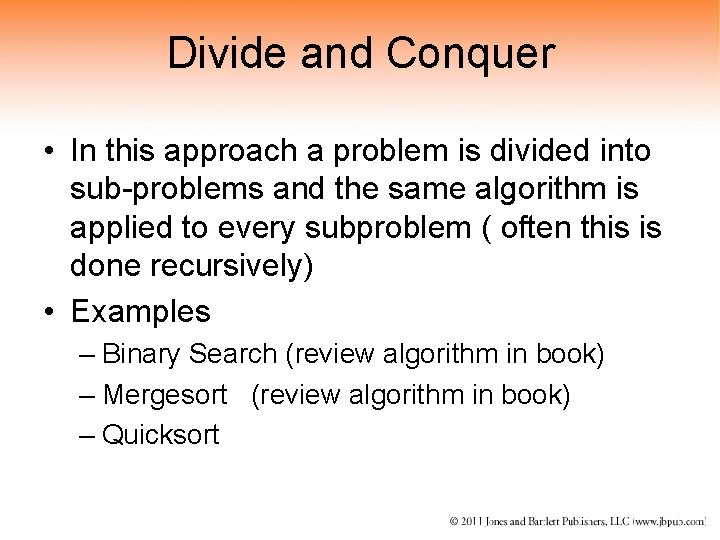

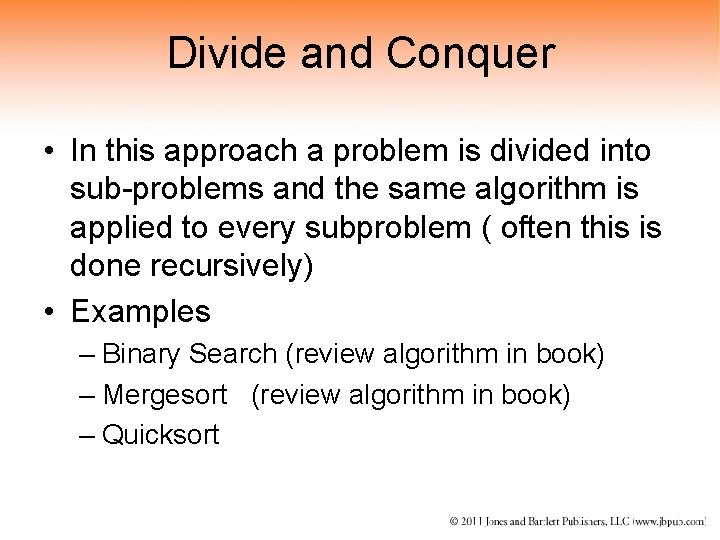

Figure 2. 1 : The steps down by a human when searching with Binary Search. (Note: x = 18)

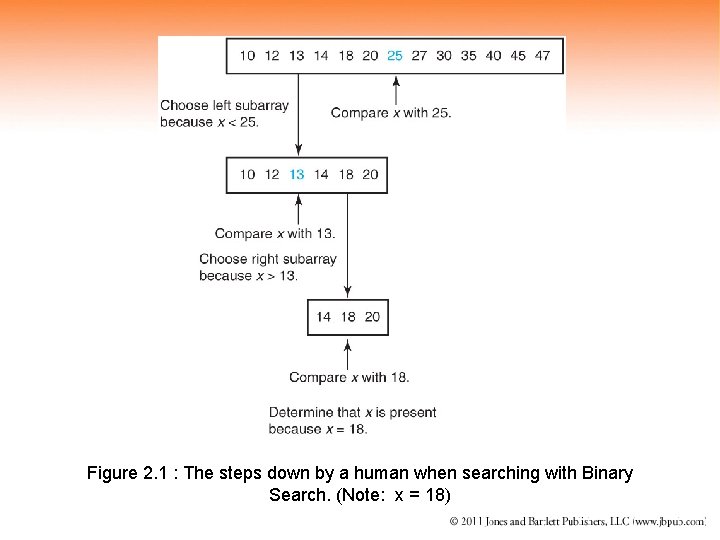

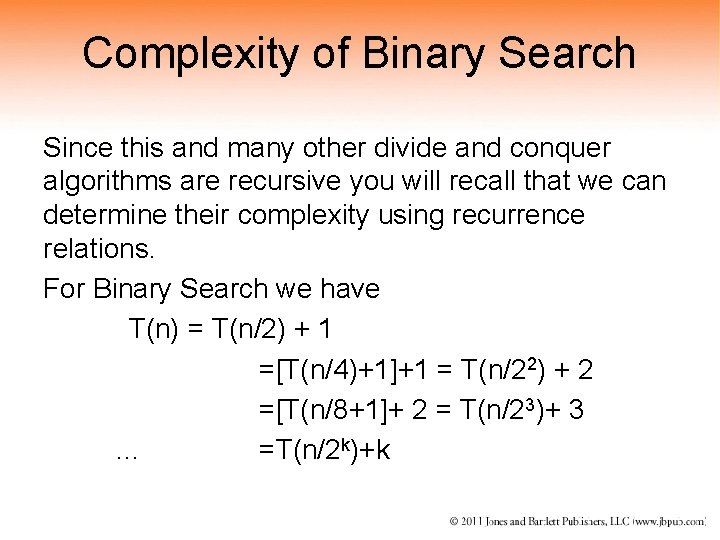

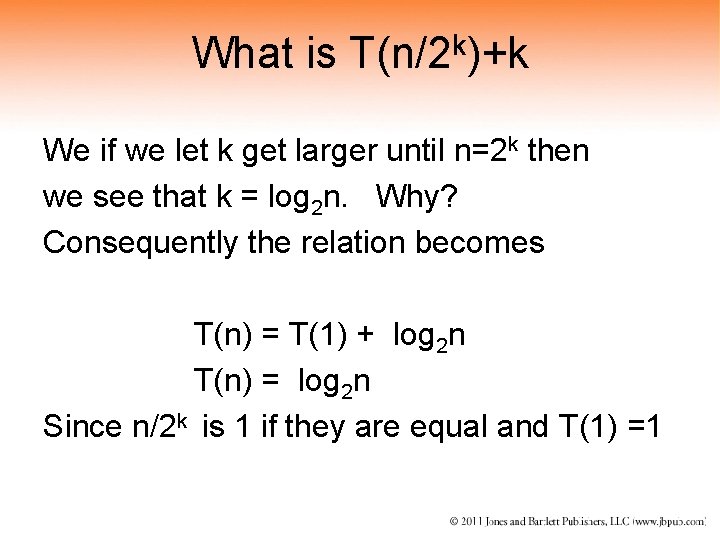

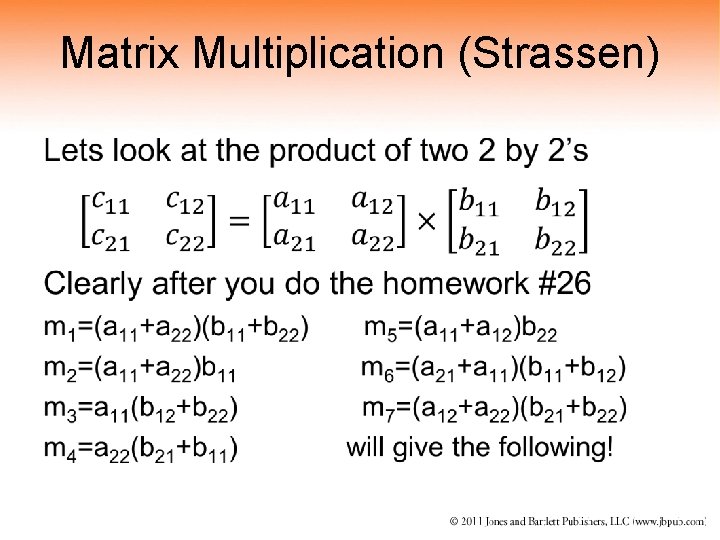

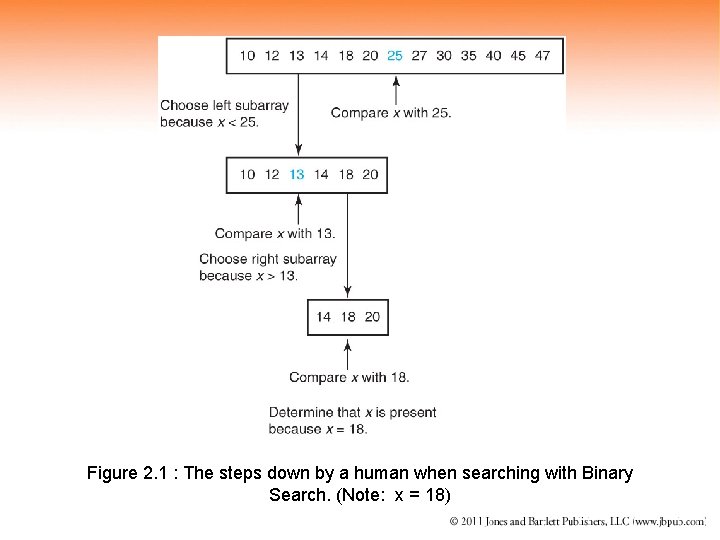

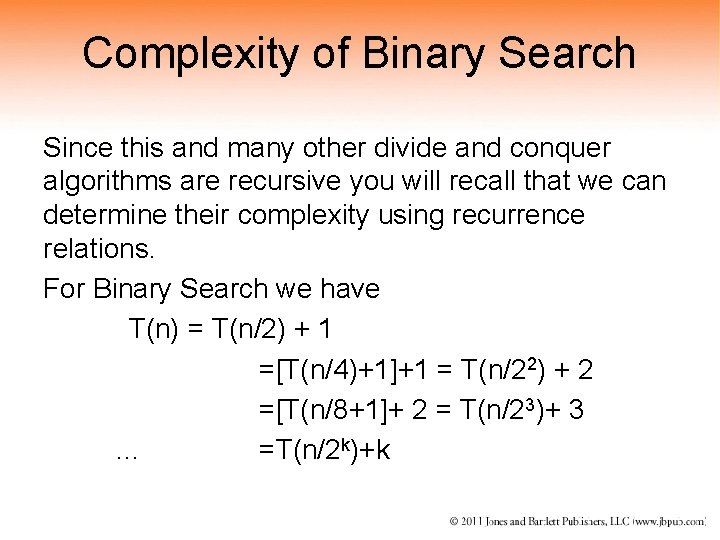

Complexity of Binary Search Since this and many other divide and conquer algorithms are recursive you will recall that we can determine their complexity using recurrence relations. For Binary Search we have T(n) = T(n/2) + 1 =[T(n/4)+1]+1 = T(n/22) + 2 =[T(n/8+1]+ 2 = T(n/23)+ 3 … =T(n/2 k)+k

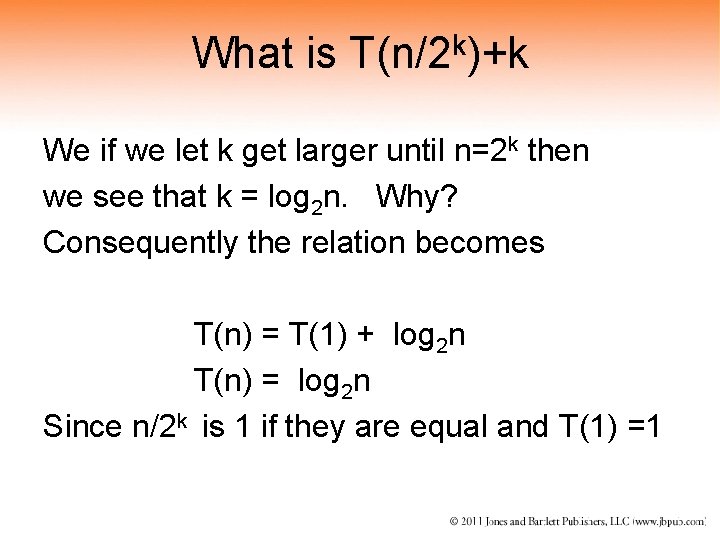

k What is T(n/2 )+k We if we let k get larger until n=2 k then we see that k = log 2 n. Why? Consequently the relation becomes T(n) = T(1) + log 2 n T(n) = log 2 n Since n/2 k is 1 if they are equal and T(1) =1

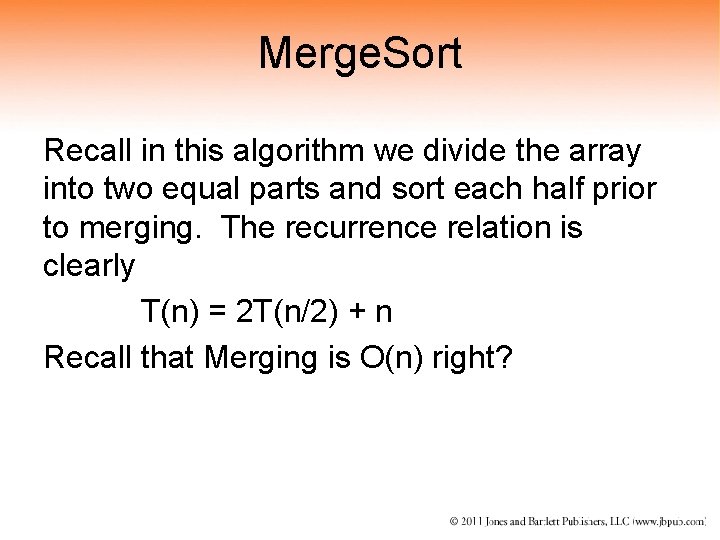

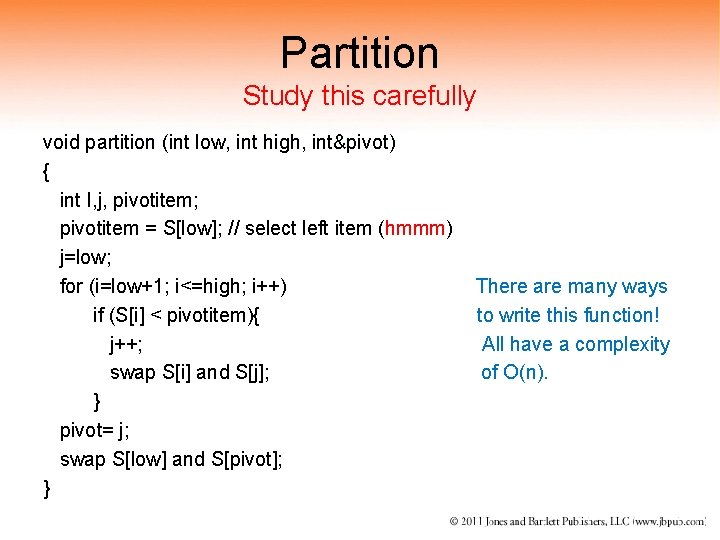

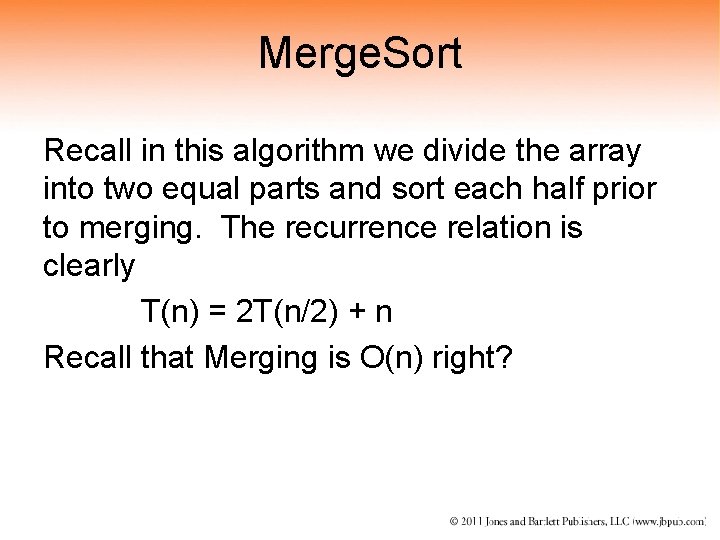

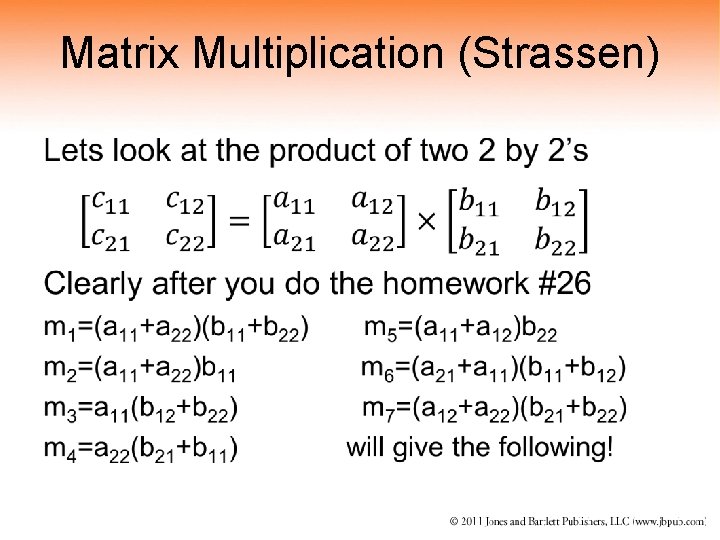

Merge. Sort Recall in this algorithm we divide the array into two equal parts and sort each half prior to merging. The recurrence relation is clearly T(n) = 2 T(n/2) + n Recall that Merging is O(n) right?

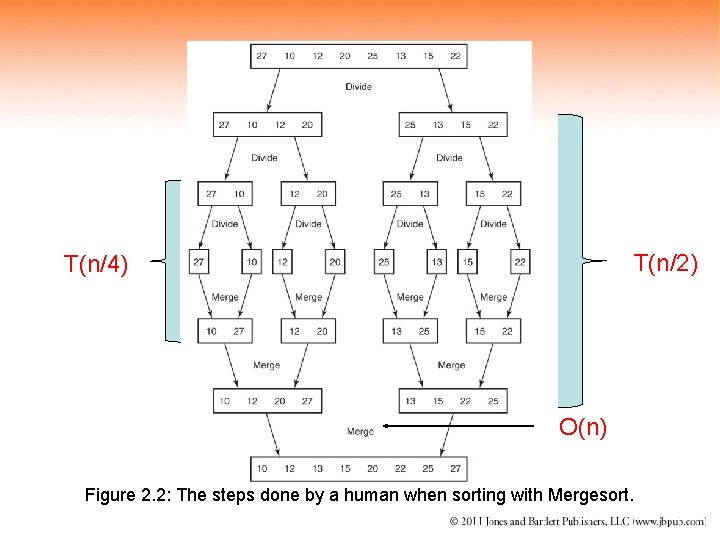

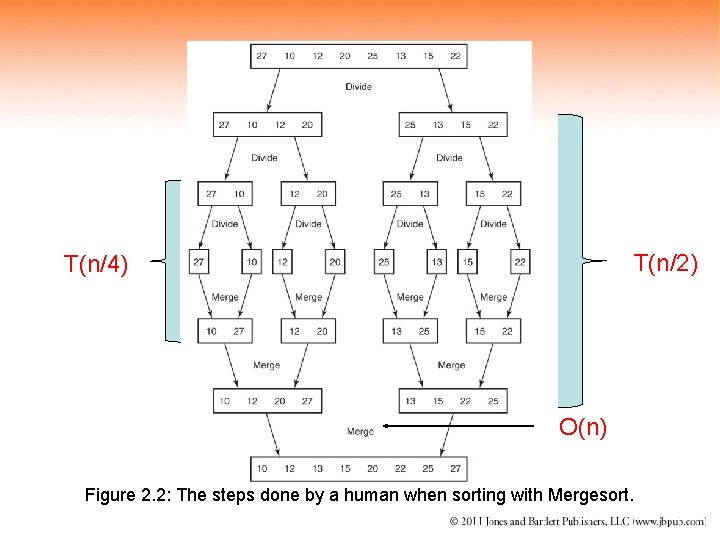

T(n/2) T(n/4) O(n) Figure 2. 2: The steps done by a human when sorting with Mergesort.

![Tn 2 Tn2 n 2 2 Tn22 n2 n T(n) = 2 T(n/2) + n = 2[ 2 T(n/22) + n/2] + n](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h/8b62b33e94e2403735d34e2a4b5f0c07/image-8.jpg)

T(n) = 2 T(n/2) + n = 2[ 2 T(n/22) + n/2] + n = 22 T(n/22) + 2 n = 2[2 T(n/23) + n/22] +2 n =23 T(n/23) + 3 n … =2 k. T(n/2 k) + kn If n=2 k then we have T(n) = n. T(1) + (log 2 n)n = n+ nlog 2 n = O(nlog 2 n)

Quick. Sort Works in situ! Void quicksort(int low, int high) { int pivot; if (high > low){ partition(low, high, pivot); quicksort(low, pivot-1); quicksort(pivot+1, high); }

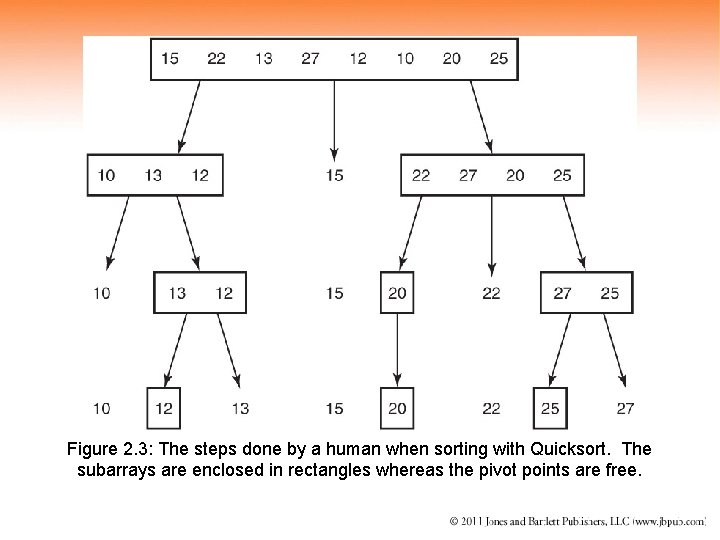

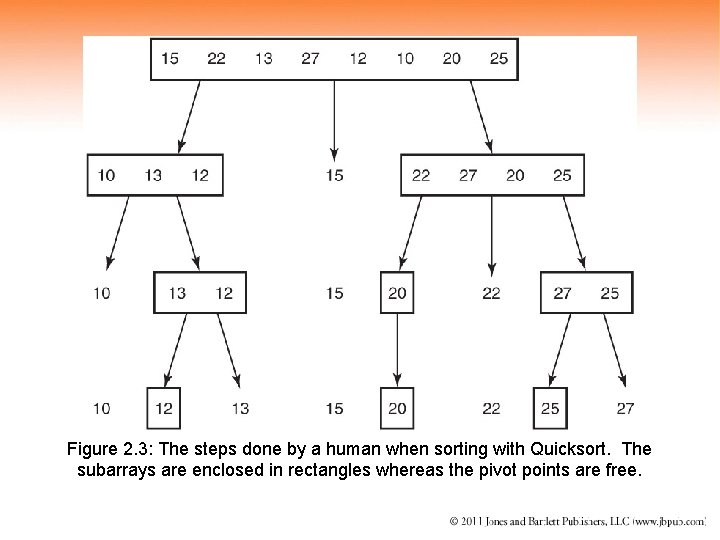

Figure 2. 3: The steps done by a human when sorting with Quicksort. The subarrays are enclosed in rectangles whereas the pivot points are free.

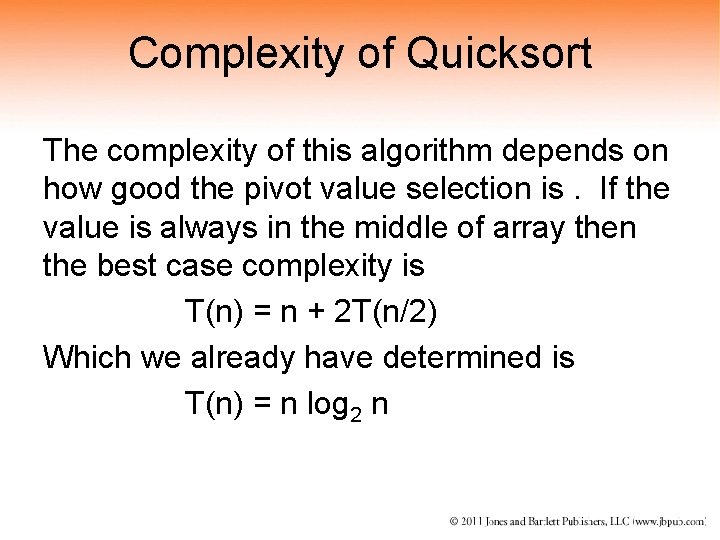

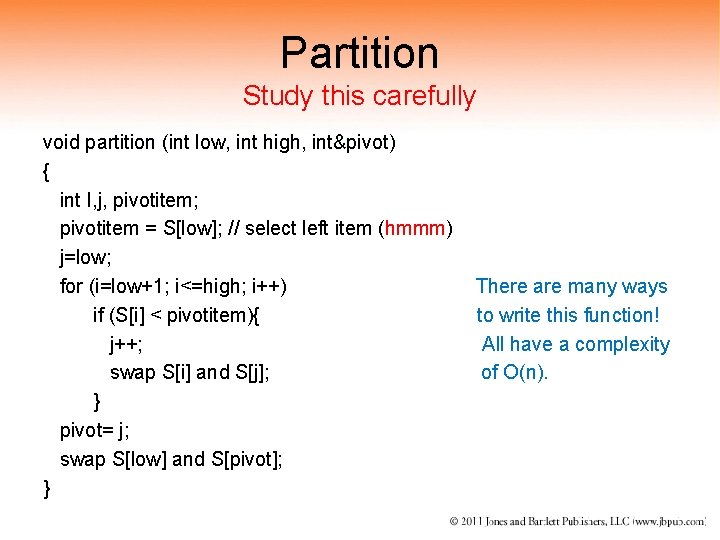

Partition Study this carefully void partition (int low, int high, int&pivot) { int I, j, pivotitem; pivotitem = S[low]; // select left item (hmmm) j=low; for (i=low+1; i<=high; i++) There are many ways if (S[i] < pivotitem){ to write this function! j++; All have a complexity swap S[i] and S[j]; of O(n). } pivot= j; swap S[low] and S[pivot]; }

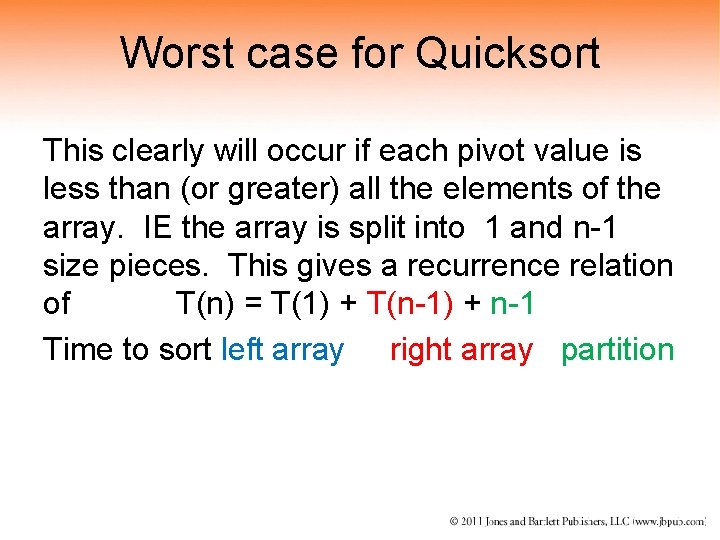

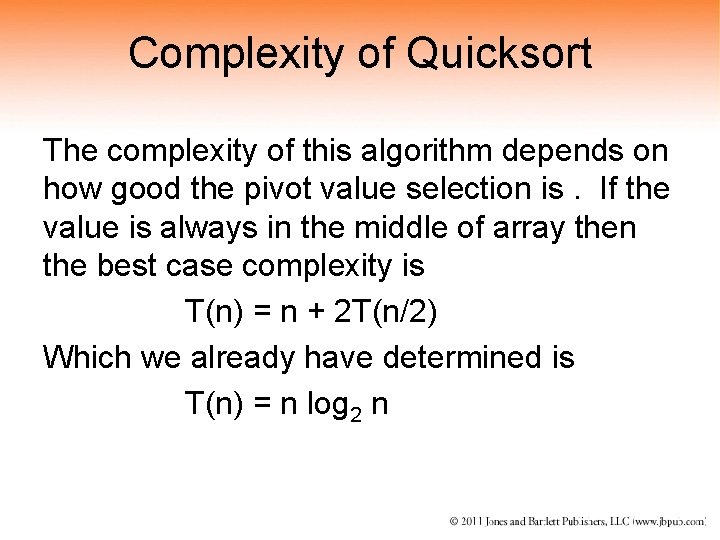

Complexity of Quicksort The complexity of this algorithm depends on how good the pivot value selection is. If the value is always in the middle of array then the best case complexity is T(n) = n + 2 T(n/2) Which we already have determined is T(n) = n log 2 n

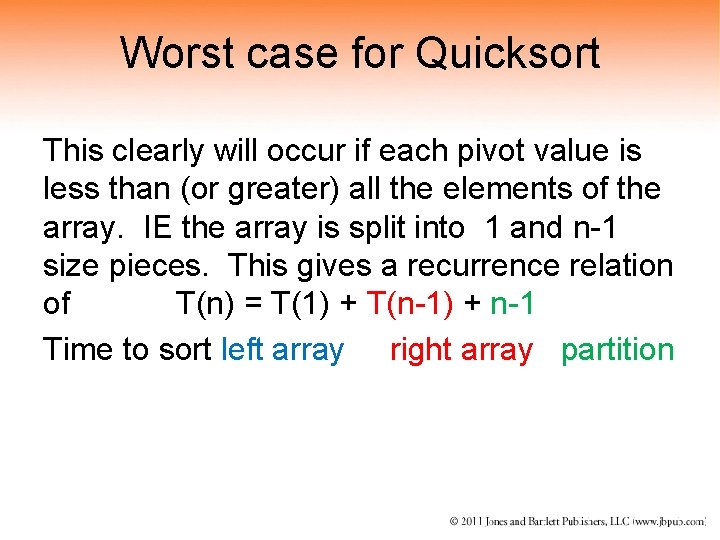

Worst case for Quicksort This clearly will occur if each pivot value is less than (or greater) all the elements of the array. IE the array is split into 1 and n-1 size pieces. This gives a recurrence relation of T(n) = T(1) + T(n-1) + n-1 Time to sort left array right array partition

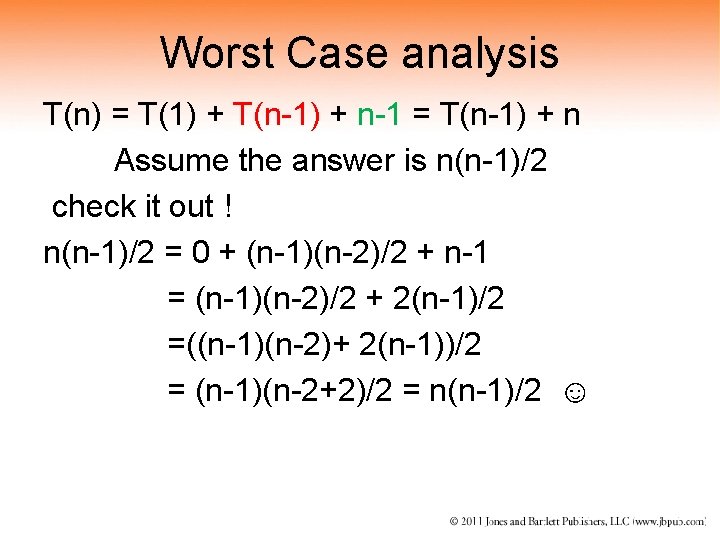

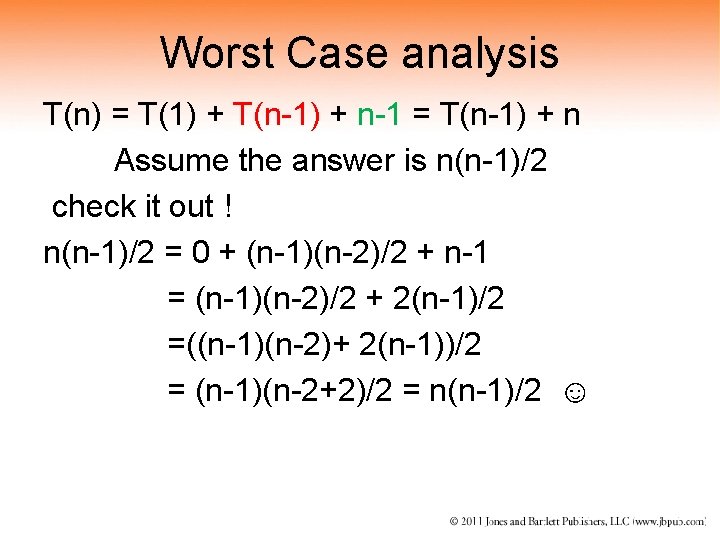

Worst Case analysis T(n) = T(1) + T(n-1) + n-1 = T(n-1) + n Assume the answer is n(n-1)/2 check it out ! n(n-1)/2 = 0 + (n-1)(n-2)/2 + n-1 = (n-1)(n-2)/2 + 2(n-1)/2 =((n-1)(n-2)+ 2(n-1))/2 = (n-1)(n-2+2)/2 = n(n-1)/2 ☺

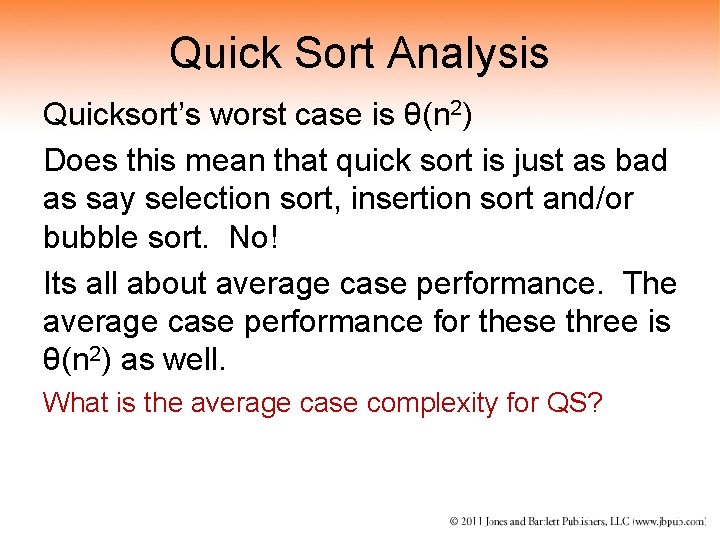

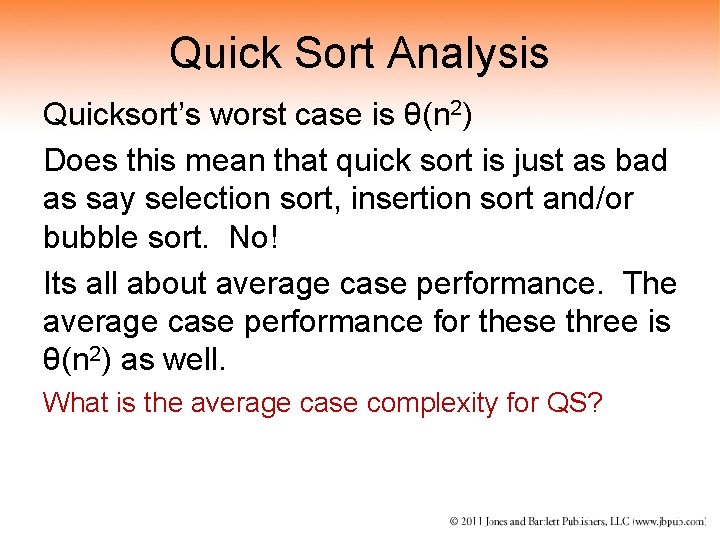

Quick Sort Analysis Quicksort’s worst case is θ(n 2) Does this mean that quick sort is just as bad as say selection sort, insertion sort and/or bubble sort. No! Its all about average case performance. The average case performance for these three is θ(n 2) as well. What is the average case complexity for QS?

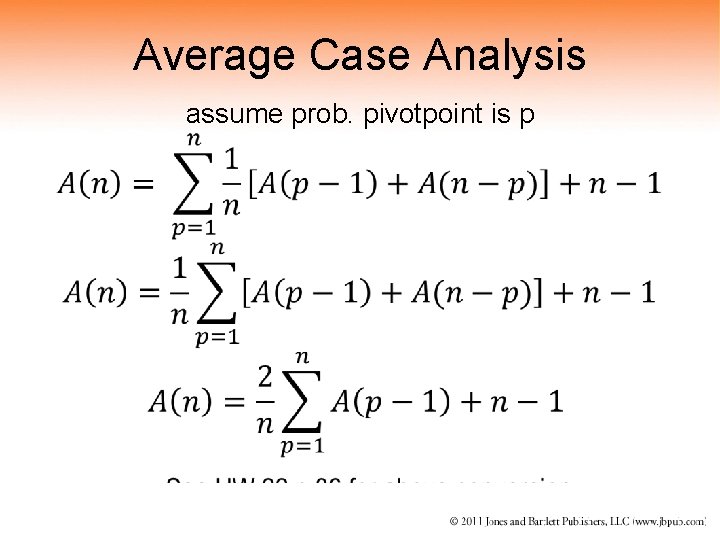

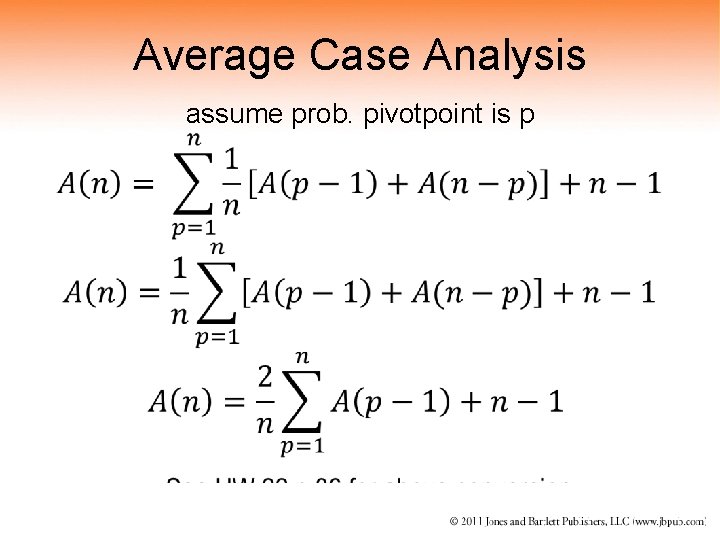

• Average Case Analysis assume prob. pivotpoint is p

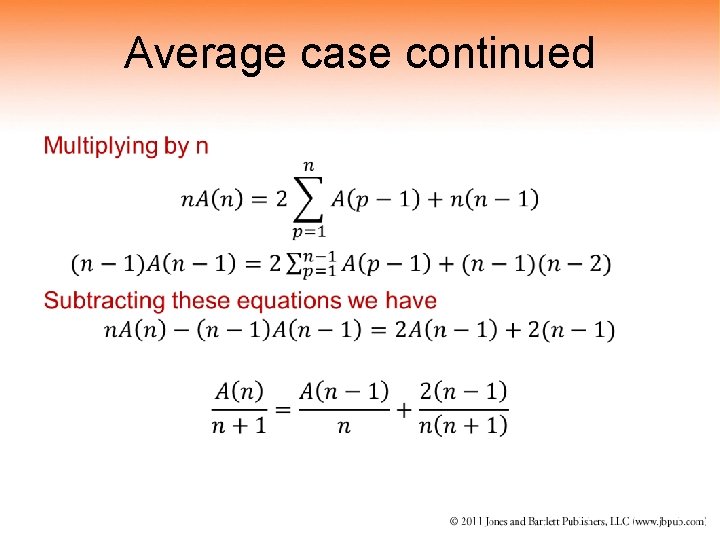

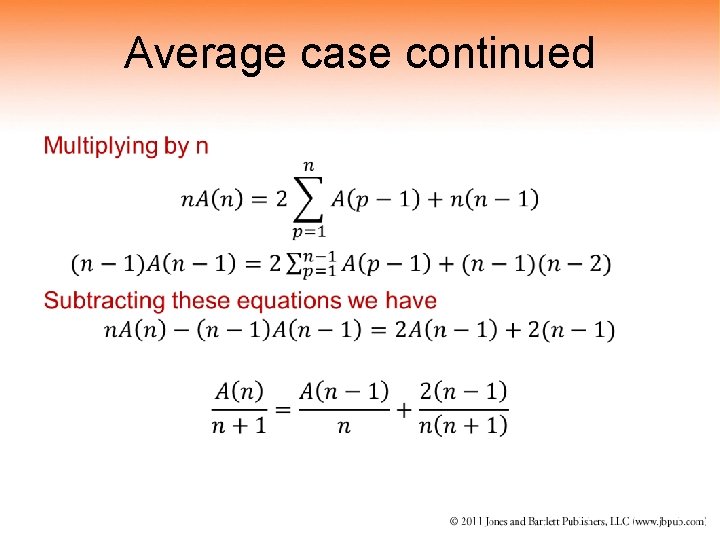

Average case continued •

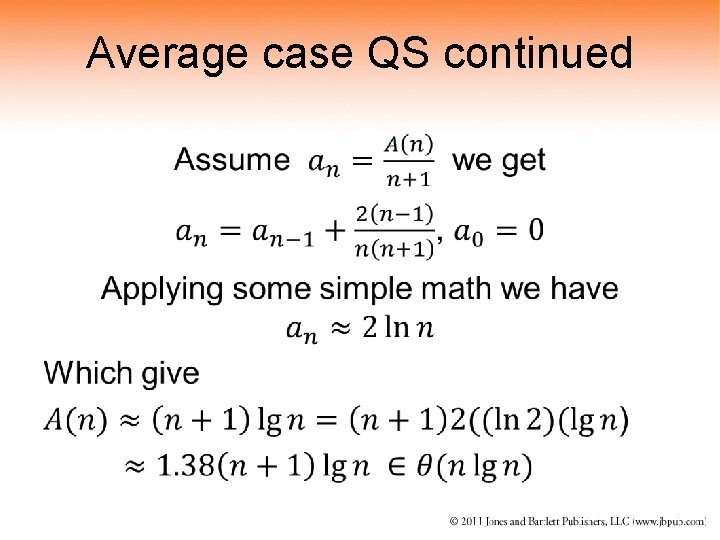

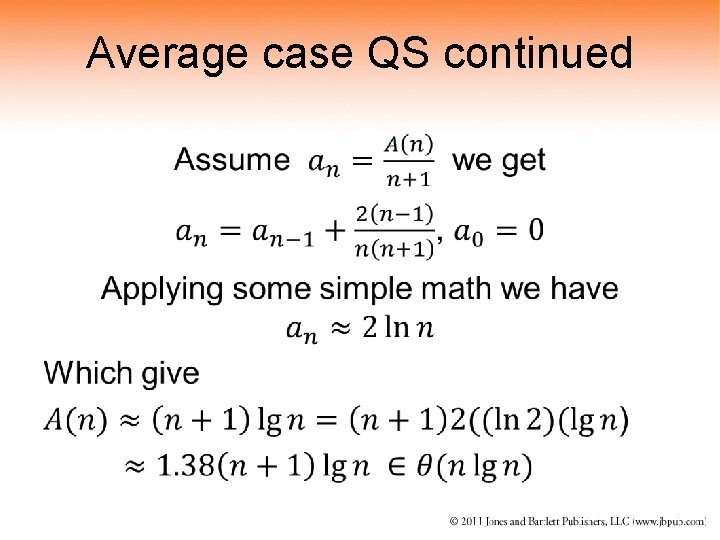

Average case QS continued •

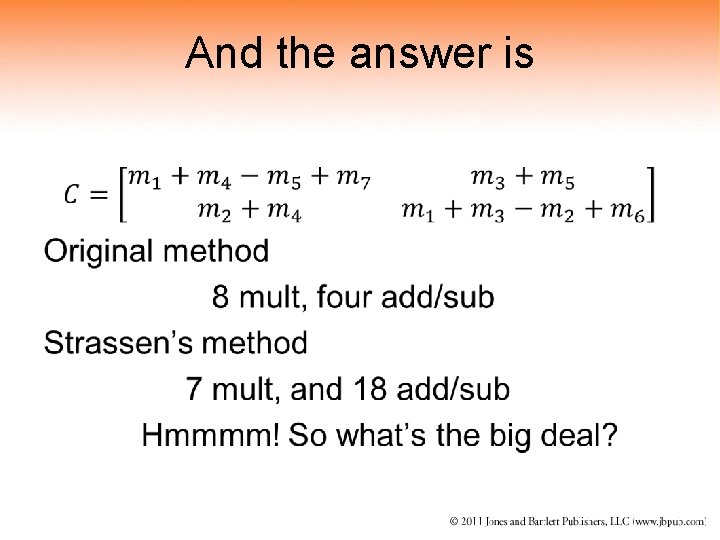

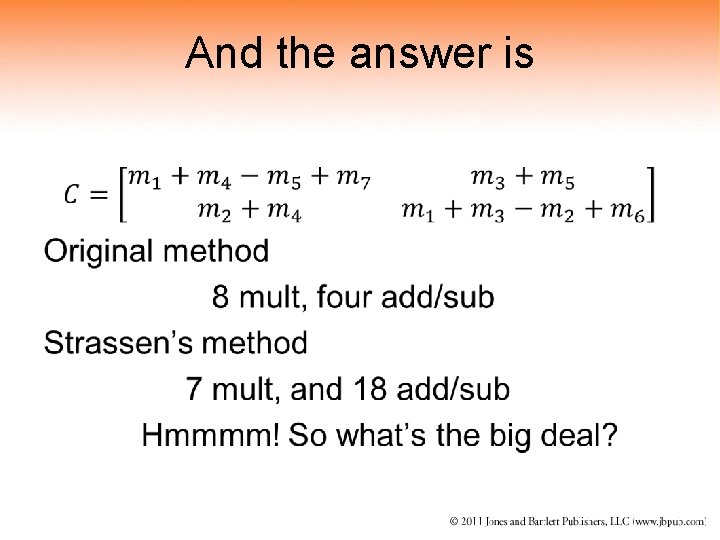

Matrix Multiplication (Strassen) •

And the answer is •

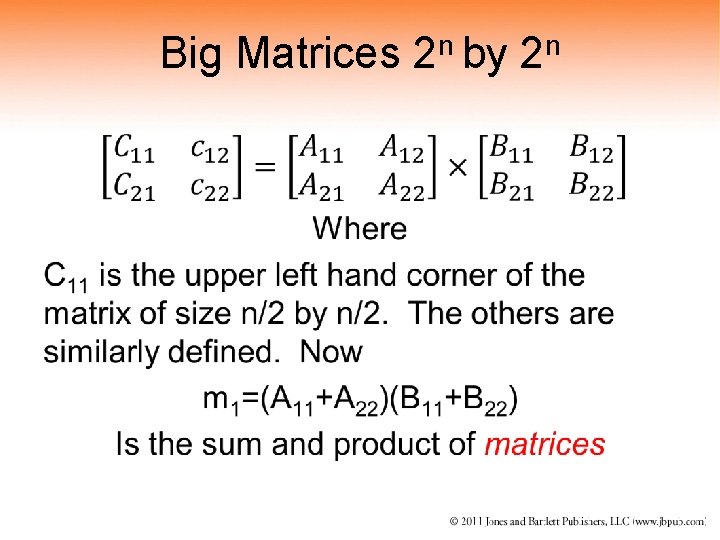

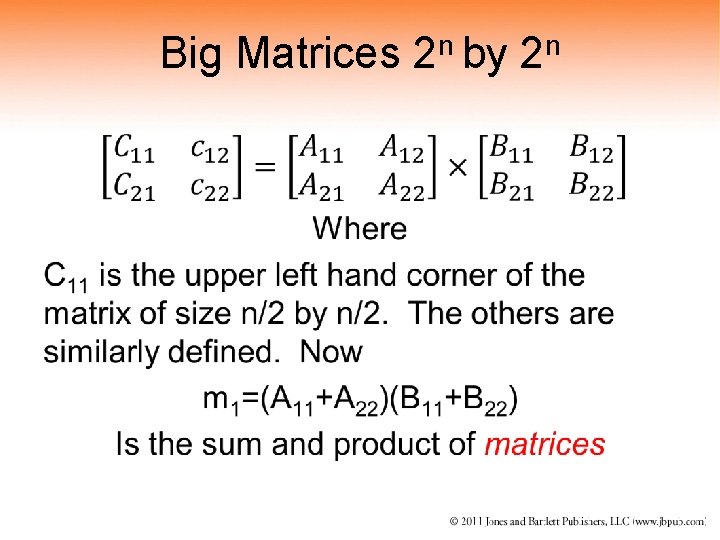

n n Big Matrices 2 by 2 •

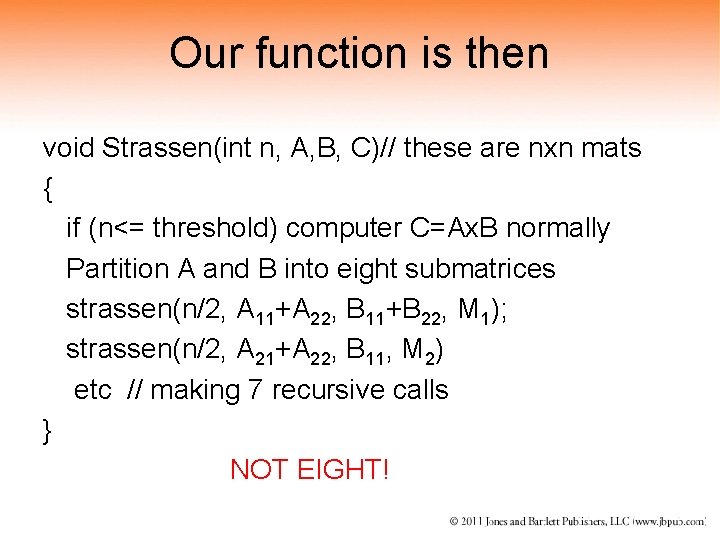

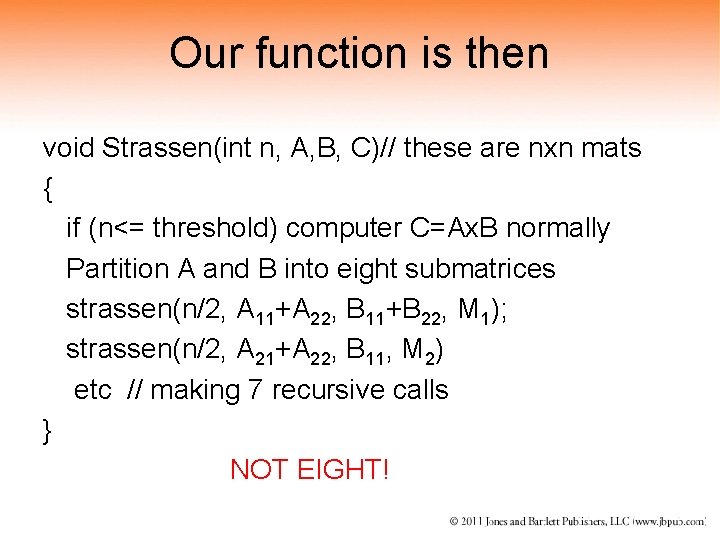

Our function is then void Strassen(int n, A, B, C)// these are nxn mats { if (n<= threshold) computer C=Ax. B normally Partition A and B into eight submatrices strassen(n/2, A 11+A 22, B 11+B 22, M 1); strassen(n/2, A 21+A 22, B 11, M 2) etc // making 7 recursive calls } NOT EIGHT!

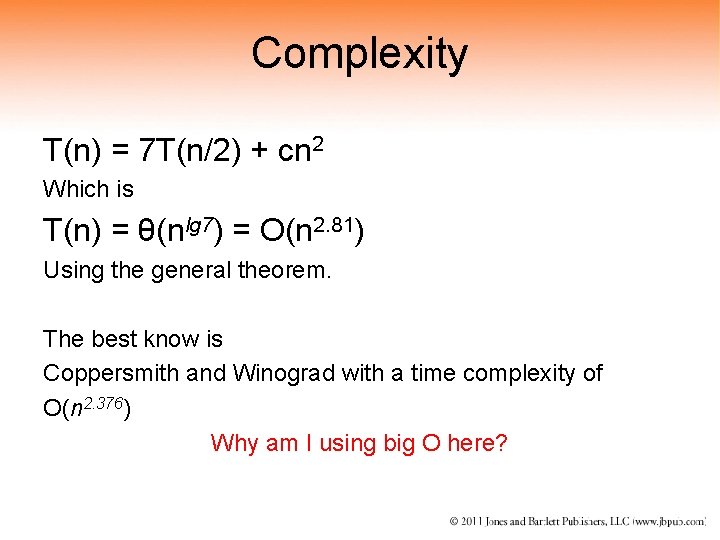

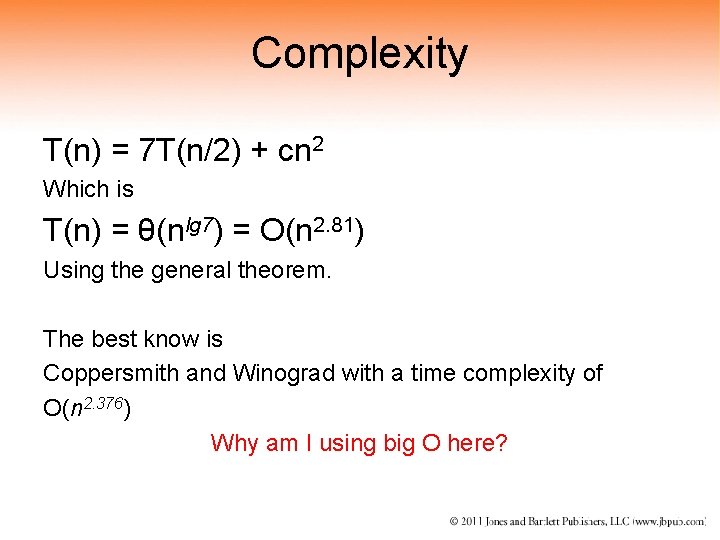

Complexity T(n) = 7 T(n/2) + cn 2 Which is T(n) = θ(nlg 7) = O(n 2. 81) Using the general theorem. The best know is Coppersmith and Winograd with a time complexity of O(n 2. 376) Why am I using big O here?

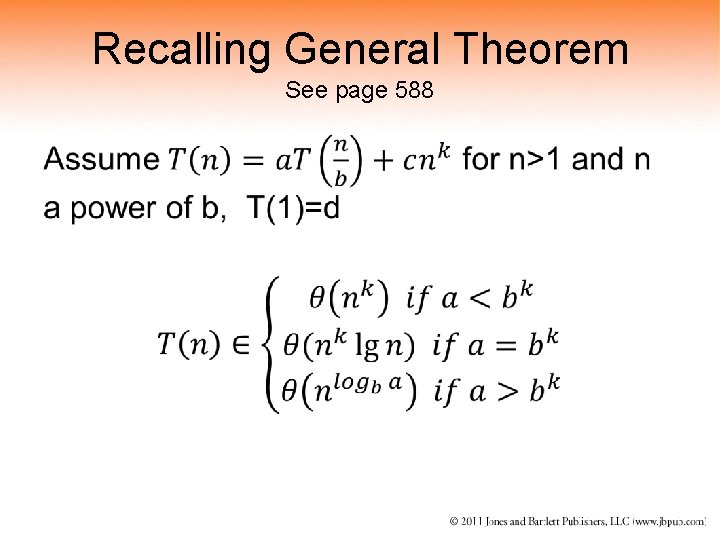

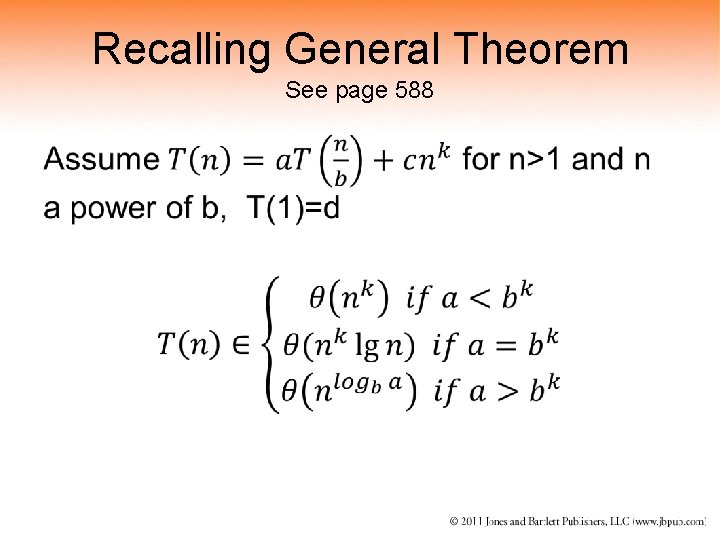

Recalling General Theorem See page 588 •

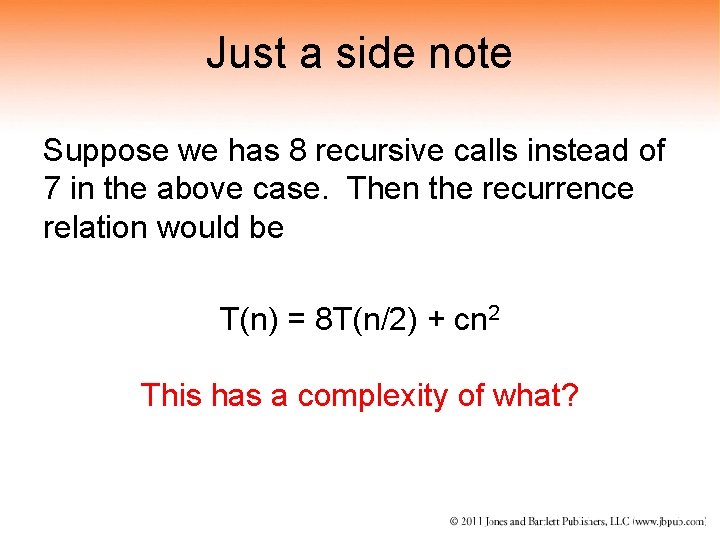

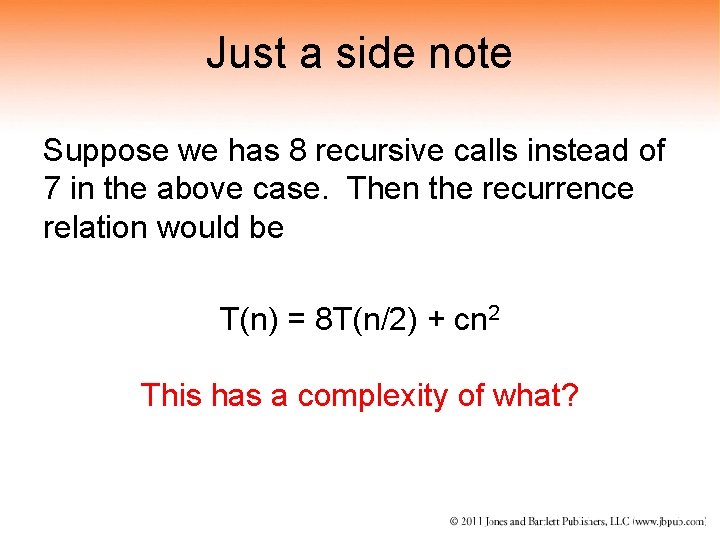

Just a side note Suppose we has 8 recursive calls instead of 7 in the above case. Then the recurrence relation would be T(n) = 8 T(n/2) + cn 2 This has a complexity of what?

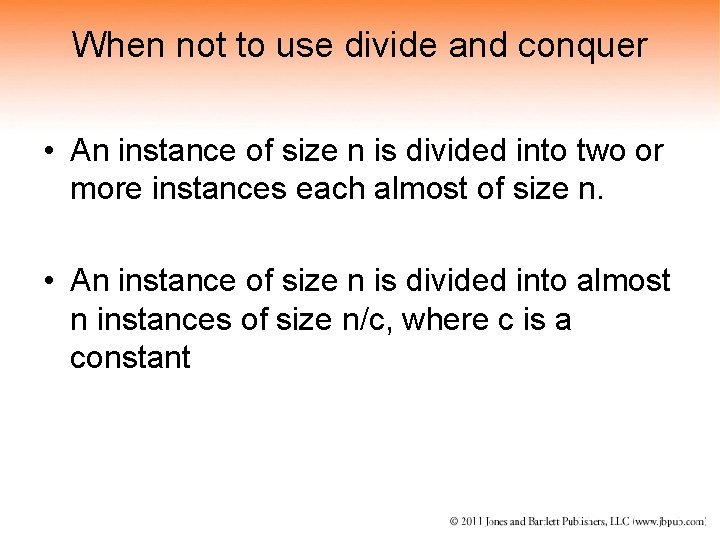

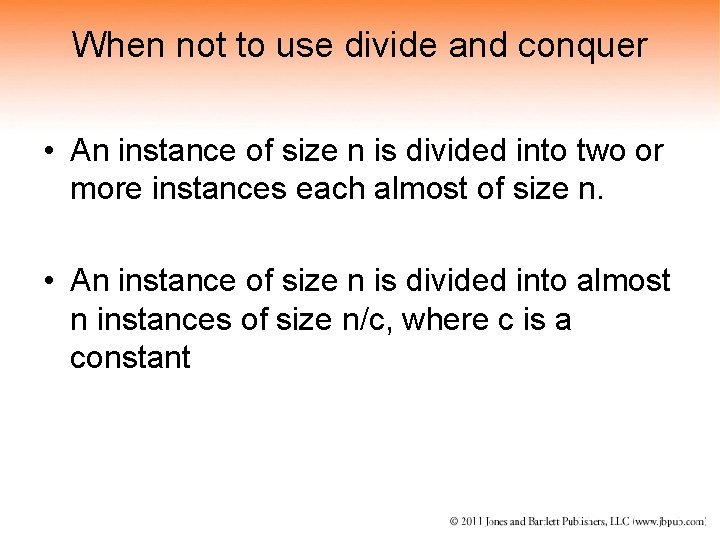

When not to use divide and conquer • An instance of size n is divided into two or more instances each almost of size n. • An instance of size n is divided into almost n instances of size n/c, where c is a constant