FORMATIVE ASSESSMENT Transforming Preschool Teachers Formative Assessment Processes

- Slides: 1

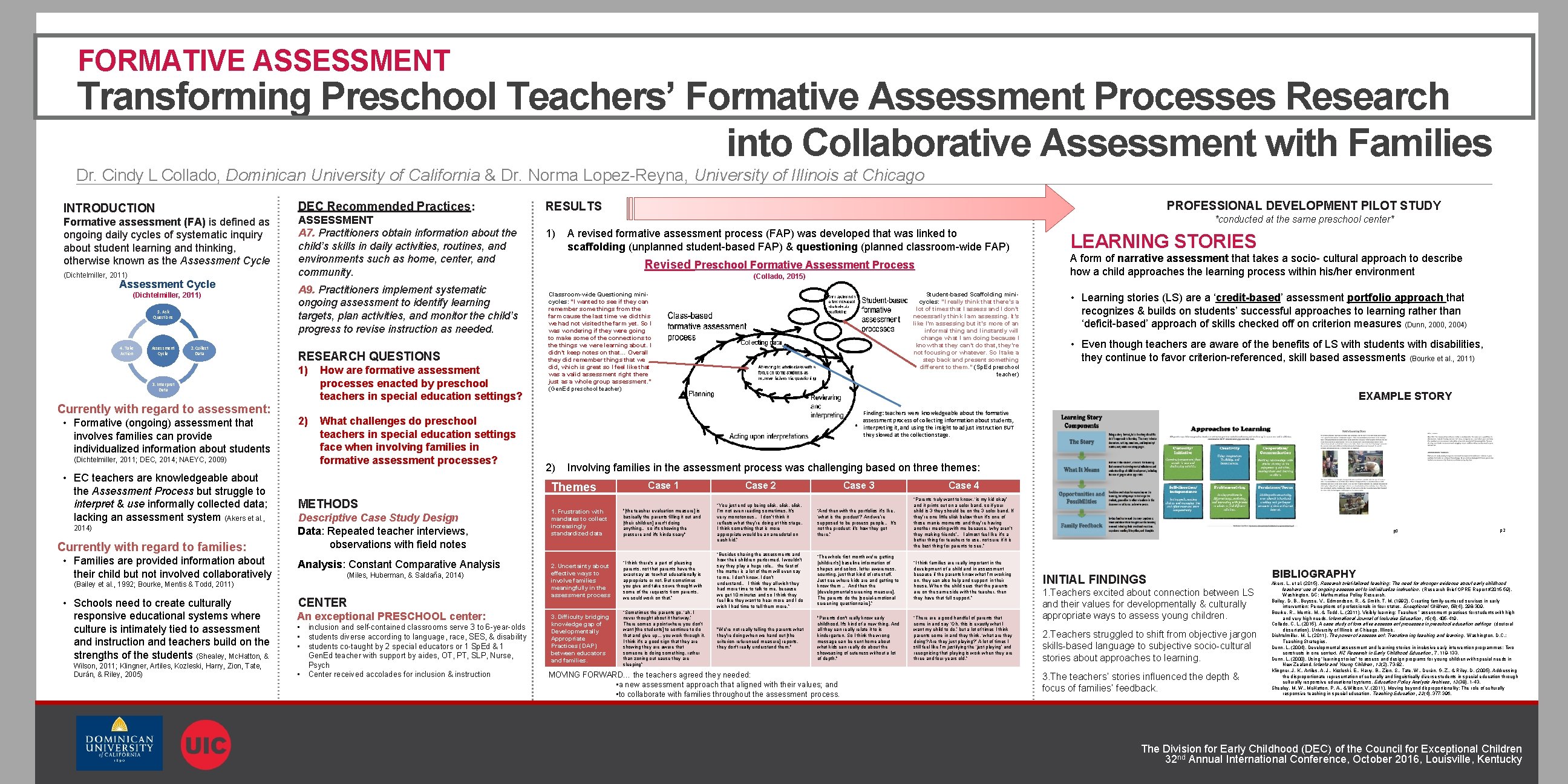

FORMATIVE ASSESSMENT Transforming Preschool Teachers’ Formative Assessment Processes Research into Collaborative Assessment with Families Dr. Cindy L Collado, Dominican University of California & Dr. Norma Lopez-Reyna, University of Illinois at Chicago DEC Recommended Practices: INTRODUCTION Formative assessment (FA) is defined as ongoing daily cycles of systematic inquiry about student learning and thinking, otherwise known as the Assessment Cycle (Dichtelmiller, 2011) 1. Ask Questions 4. Take Action Assessment Cycle 2. Collect Data ASSESSMENT A 7. Practitioners obtain information about the child’s skills in daily activities, routines, and environments such as home, center, and community. A 9. Practitioners implement systematic ongoing assessment to identify learning targets, plan activities, and monitor the child’s progress to revise instruction as needed. RESEARCH QUESTIONS 1) 3. Interpret Data Currently with regard to assessment: • Formative (ongoing) assessment that involves families can provide individualized information about students 2) (Dichtelmiller, 2011; DEC, 2014; NAEYC, 2009) • EC teachers are knowledgeable about the Assessment Process but struggle to interpret & use informally collected data; lacking an assessment system (Akers et al. , 2014) Currently with regard to families: • Families are provided information about their child but not involved collaboratively How are formative assessment processes enacted by preschool teachers in special education settings? What challenges do preschool teachers in special education settings face when involving families in formative assessment processes? Descriptive Case Study Design Data: Repeated teacher interviews, observations with field notes Analysis: Constant Comparative Analysis (Miles, Huberman, & Saldaña, 2014) (Bailey et al. , 1992; Bourke, Mentis & Todd, 2011) • Schools need to create culturally responsive educational systems where culture is intimately tied to assessment and instruction and teachers build on the strengths of the students (Shealey, Mc. Hatton, & Wilson, 2011; Klingner, Artiles, Kozleski, Harry, Zion, Tate, Durán, & Riley, 2005) *conducted at the same preschool center* 1) A revised formative assessment process (FAP) was developed that was linked to scaffolding (unplanned student-based FAP) & questioning (planned classroom-wide FAP) Revised Preschool Formative Assessment Process (Collado, 2015) Classroom-wide Questioning minicycles: “I wanted to see if they can remember some things from the farm cause the last time we did this we had not visited the farm yet. So I was wondering if they were going to make some of the connections to the things we were learning about. I didn’t keep notes on that… Overall they did remember things that we did, which is great so I feel like that was a valid assessment right there just as a whole group assessment. ” (Gen. Ed preschool teacher) CENTER An exceptional PRESCHOOL center: • • inclusion and self-contained classrooms serve 3 to 6 -year-olds students diverse according to language, race, SES, & disability students co-taught by 2 special educators or 1 Sp. Ed & 1 Gen. Ed teacher with support by aides, OT, PT, SLP, Nurse, Psych Center received accolades for inclusion & instruction Student-based Scaffolding minicycles: “I really think that there’s a lot of times that I assess and I don’t necessarily think I am assessing. It’s like I’m assessing but it’s more of an informal thing and I instantly will change what I am doing because I know that they can’t do that, they’re not focusing or whatever. So I take a step back and present something different to them. ” (Sp. Ed preschool teacher) LEARNING STORIES A form of narrative assessment that takes a socio- cultural approach to describe how a child approaches the learning process within his/her environment • Learning stories (LS) are a ‘credit-based’ assessment portfolio approach that recognizes & builds on students’ successful approaches to learning rather than ‘deficit-based’ approach of skills checked off on criterion measures (Dunn, 2000, 2004) • Even though teachers are aware of the benefits of LS with students with disabilities, they continue to favor criterion-referenced, skill based assessments (Bourke et al. , 2011) EXAMPLE STORY Finding: teachers were knowledgeable about the formative assessment process of collecting information about students, interpreting it, and using the insight to adjust instruction BUT they slowed at the collection stage. 2) Involving families in the assessment process was challenging based on three themes: Themes METHODS PROFESSIONAL DEVELOPMENT PILOT STUDY RESULTS Case 1 Case 2 Case 3 Case 4 "[the teacher evaluation measure] is basically the parents filling it out and [their children] aren't doing anything… so it's showing the pressure and it's kinda scary" “You just end up being click, click. I’m not even reading sometimes. It’s very monotonous… I don’t think it reflects what they’re doing at this stage. I think something that is more appropriate would be an anecdotal on each kid. ” “And then with the portfolios it’s like, ‘what is the product? ’ And we’re supposed to be process people… It’s not the product; it’s how they got there. ” “Parents truly want to know, ‘is my kid okay’ and it prints out on a color band, so if your child is 3 they should be on the 3 color band. If they’re one little click below then it’s one of those manic moments and they’re having another meeting with me because, ‘why aren’t they making friends’… I almost feel like it’s a better thing for teachers to use, not sure if it is the best thing for parents to see. ” 2. Uncertainty about effective ways to involve families meaningfully in the assessment process “I think there's a part of pleasing parents, not that parents have the exact say as to what educationally is appropriate or not. But sometimes you give and take so we thought with some of the requests from parents, we could work on that. ” “Besides sharing the assessments and how their children performed, I wouldn’t say they play a huge role… the fact of the matter is a lot of them will even say to me, I don’t know, I don’t understand… I think they all wish they had more time to talk to me, because we get 10 minutes and so I think they feel like they want to hear more and I do wish I had time to tell them more. ” “The whole first month we're getting [children’s] baseline information of shapes and colors, letter awareness, counting, just that kind of rote stuff. Just see where kids are and getting to know them … And then the [developmental screening measure]. The parents do the [social-emotional screening questionnaire]. ” “I think families are really important in the development of a child and in assessment because if the parents know what I’m working on, they can also help and support in their house. When the child sees that the parents are on the same side with the teacher, then they have that full support. ” 3. Difficulty bridging knowledge gap of Developmentally Appropriate Practices (DAP) between educators and families. “Sometimes the parents go, ‘ah, I never thought about it that way. ’ There comes a point where you don’t want [the students] to continue to do that and give up. . . you work through it. I think it’s a good sign that they are showing they are aware that someone is doing something, rather than zoning out cause they are sleeping” "We're not really telling the parents what they're doing when we hand out [the criterion-referenced measure] reports, they don't really understand them. " "Parents don't really know early childhood. It's kind of a new thing. And all they can really relate it to is kindergarten. So I think the wrong message can be sent home about what kids can really do about the showcasing of cuteness without a lot of depth. " “There a good handful of parents that come in and say ‘Oh, this is exactly what I want my child to do, ’ but a lot of times I think parents come in and they think, ‘what are they doing? Are they just playing? ’ A lot of times I still feel like I’m justifying the ‘just playing’ and recognizing that playing is work when they are three and four years old. ” 1. Frustration with mandates to collect increasingly standardized data MOVING FORWARD… the teachers agreed they needed: • a new assessment approach that aligned with their values; and • to collaborate with families throughout the assessment process. p 1 INITIAL FINDINGS 1. Teachers excited about connection between LS and their values for developmentally & culturally appropriate ways to assess young children. 2. Teachers struggled to shift from objective jargon skills-based language to subjective socio-cultural stories about approaches to learning. 3. The teachers’ stories influenced the depth & focus of families’ feedback. p 2 BIBLIOGRAPHY Akers, L. et al. (2015). Research brief-tailored teaching: The need for stronger evidence about early childhood teachers’ use of ongoing assessment to individualize instruction. (Research Brief OPRE Report #2015 -59). Washington, DC: Mathematica Policy Research. Bailey, D. B. , Buysse, V. , Edmondson, R. , & Smith, T. M. (1992). Creating family-centered services in early intervention: Perceptions of professionals in four states. Exceptional Children, 58(4), 298 -309. Bourke, R. , Mentis, M. , & Todd, L. (2011). Visibly learning: Teachers ’ assessment practices for students with high and very high needs. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 15 (4), 405 -419. Collado, C. L. (2015). A case study of formative assessment processes in preschool education settings (doctoral dissertation). University of Illinois at Chicago, Illinois. Dichtelmiller, M. L. (2011). The power of assessment: Transforming teaching and learning. Washington, D. C. : Teaching Strategies. Dunn, L. (2004). Developmental assessment and learning stories in inclusive early intervention programmes: Two constructs in one context. NZ Research in Early Childhood Education, 7, 119 -133. Dunn, L. (2000). Using “learning stories” to assess and design programs for young children with special needs in New Zealand. Infants and Young Children, 13 (2), 73 -82. Klingner, J. K. , Artiles, A. J. , Kozleski, E. , Harry, B. , Zion, S. , Tate, W. , Durán, G. Z. , & Riley, D. (2005). Addressing the disproportionate representation of culturally and linguistically diverse students in special education through culturally responsive educational systems. Education Policy Analysis Archives, 13 (38), 1 -43. Shealey, M. W. , Mc. Hatton, P. A. , & Wilson, V. (2011). Moving beyond disproportionality: The role of culturally responsive teaching in special education. Teaching Education, 22(4), 377 -396. The Division for Early Childhood (DEC) of the Council for Exceptional Children 32 nd Annual International Conference, October 2016, Louisville, Kentucky