Fluid and AcidBase Balance Stable positive and negative

Fluid and Acid/Base Balance Stable, positive and negative balance Homeostasis = maintenance of stable balances

For any reversible reaction at equilibrium Thus, changing the concentration of any reactant (A, B or AB) changes the concentration of all reactants. If (for example) A goes up, B must go down and AB must go up in order to keep that ratio from changing. Vocabulary: AB dissociates into A + B associate to form AB This is a general case. Specifics include things like Na. Cl dissociating into Na + Cl, Na. OH dissociating into Na + OH, HCl dissociating into H + Cl

Acids When one of the dissociation products is H+, the substance is an acid. It contributes protons to the medium. Its other dissociation product, an anion, is sometimes called its conjugate salt Water dissociates: H 2 O -- H+ + OHAt equilibrium: K = [H+][OH-]/[H 2 O] Rearranging the equilibrium equation for water, we get K[H 2 O] = [H+][OH-] Since [H 2 O] as a solute is around 55. 5 M and neither [H+] nor [OH-] exceed 1 M, K[H 2 O] is essentially a constant itself. Let’s call it K’

For most reversible equilibria, K is known. Knowing it for a simple dissociation tells you whether the equilibrium concentrations have high concentrations of the undissociated substance and low concentrations of the dissociated species, or vice versa. The value of K’ for water = 10 exp -14. Most textbooks call this K for water. It isn’t, it’s K x 55. 5 M When H+ and OH- are at equal concentrations in water, their concentrations are each 10 exp -7 M. H+ ion concentrations can range all the way from 1 M to 10 exp -14 M, which makes it awkward to express them in simple numerals. For that reason, they’re usually expressed as logarithms, powers of 10. For example, log (0. 0000001 M) = log (1 exp -7 M) = -7. In order to eliminate the negative sign, it’s conventional to express H+ concentrations as the negative of their logarithms. Thus, -log (0. 0000001 M) = 7.

The convention is to call the negative of the logarithm of the H+ concentration p. H When [H+] = 0. 0000007 M, log [H+] = -7, p. H = 7 When an aqueous solution is at p. H 7, [H+] and [OH-] are equal. For that reason, p. H 7 is called neutral p. H for water Here are the minimal things to know about p. H: 1. When H+ goes up, p. H goes down (and vice-versa). 2. Each tenfold change in H+ concentration corresponds to a change of 1 p. H unit.

Acid-Base Balance Normal arterial plasma p. H is about 7. 45 Normal venous plasma p. H is about 7. 35 Therefore, normal plasma p. H is around 7. 4 Any plasma p. H below those values is called acidosis Any plasma p. H above those values is called alkalosis Acidosis and alkalosis are normal, not necessarily pathological. The limits of arterial plasma p. H that we can survive for more than a matter of minutes are from about p. H 6. 8 to about p. H 8. 0. That’s about a 15 -fold range of H+ concentrations.

Acidosis depresses neural activity, can cause coma if it gets severe enough (around p. H 7. 0 or below). Alkalosis makes neurons hyperexcitable. This causes tingling, false sensations, muscle spasms and convulsions. The usual problem in maintaining normal plasma p. H is getting rid of H+

Sources of H+ in plasma Ingestion of acids. Usually not very significant. Metabolism – three major sources CO 2, which hydrates to form H 2 CO 3, which dissociates into H+ and HCO 3 - Adding CO 2 thus adds H+ Meat digestion produces some inorganic acids (mostly sulfates and phosphates) plus some inorganic bases. Usually much more acids than bases Metabolically produced organic acids. For example, muscles produce lactic acid during anaerobic exercise Pathological situations Vomiting, in which large amounts of acids that would be absorbed in the gut are lost. This causes alkalosis. Diarrhea, in which large amounts of alkaline solutions that would be absorbed in the gut are lost. This causes acidosis

How do we restore plasma p. H to normal levels after variations that occur every day? There are three broad categories of mechanisms. First, chemical buffers. They act instantly, but are of little practical importance because their capacity is so low in plasma. This requires a brief digression, to show you how chemical buffers work.

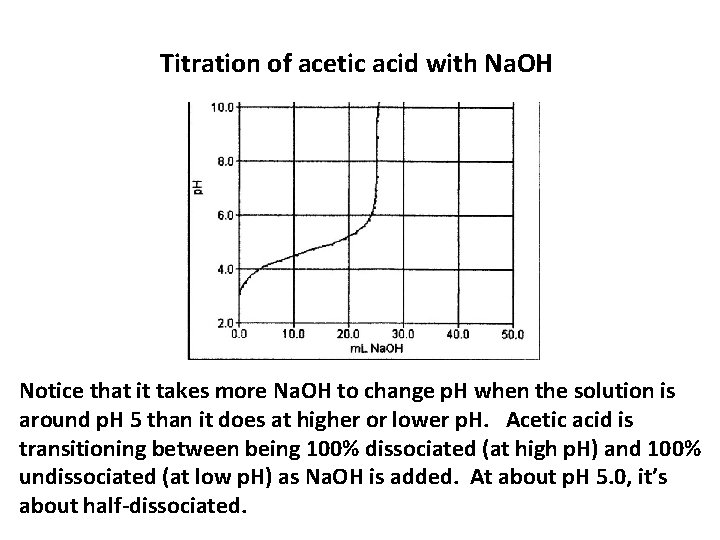

Titration of acetic acid with Na. OH Notice that it takes more Na. OH to change p. H when the solution is around p. H 5 than it does at higher or lower p. H. Acetic acid is transitioning between being 100% dissociated (at high p. H) and 100% undissociated (at low p. H) as Na. OH is added. At about p. H 5. 0, it’s about half-dissociated.

The p. H at which an acid is 50% dissociated is called its p. K. It’s easy to prove that the p. K for any acid is the negative of the logarithm of K for that acid. I’m not going to bother you with the proof; if you’re interested, look up Henderson-Hasselbach equation. Acids in which the proton is bound only loosely (lose it easily) are strong acids. For strong acids, p. K is low. Sulfuric and hydrochloric acids, for example, both have p. K around 1. For weak acids, p. K is higher. Acetic acid, for example, has p. K around 5.

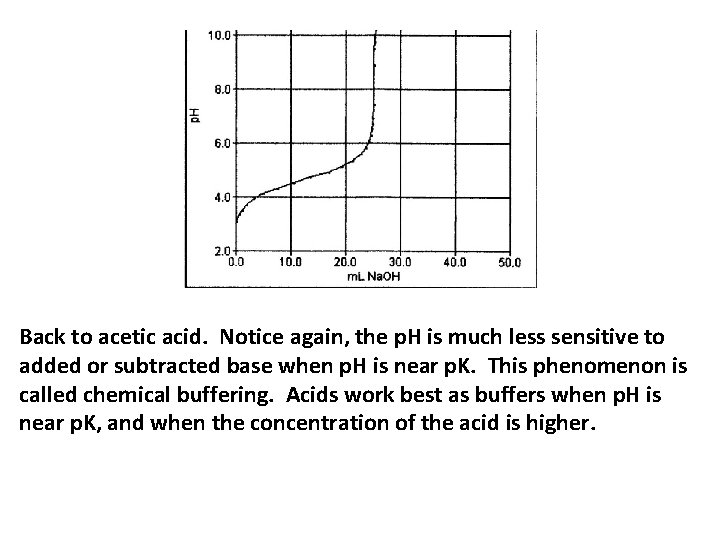

Back to acetic acid. Notice again, the p. H is much less sensitive to added or subtracted base when p. H is near p. K. This phenomenon is called chemical buffering. Acids work best as buffers when p. H is near p. K, and when the concentration of the acid is higher.

Back to chemical buffers in plasma. The one in largest quantity is the bicarbonate. Because p. K = 6. 1, its buffering power is weak at p. H 7. 4. Still, it’s the most important chemical buffer in plasma just because there’s so much of it. But it really doesn’t do much. The second major circulating buffers are proteins, especially hemoglobin. Why hemoglobin? Because there’s so much of it. Hemoglobin reversibly binds H+ (remember the Bohr effect? ). Finally, there’s buffering by phosphate. Phosphate buffer has a p. K near 7. 8, so it’s a pretty good buffer at plasma p. H. Problem is, there’s not much of it. Bottom line on chemical buffers: They’re very fast, but don’t do much buffering in plasma.

Respiratory Buffering We vary the rate of loss of CO 2 (hence, of H+) by varying the depth and rate of respiration. The respiratory control center in the medulla increases respiration depth and rate when plasma p. H falls, decreases it when plasma p. H rises. In addition, autoregulation of bronchiolar smooth muscle decreases airway resistance and relaxes constriction of arteriolar smooth muscle, increasing blood flow to the pulmonary capillaries as plasma p. H falls, further increasing gas exchange. This system has an enormous capacity. If you suspend respiration, plasma H+ concentration more than doubles within a minute! If you hyperventilate, plasma H+ concentration is halved within a minute. The story would end here, except for one thing. The system very quickly brings alkalosis or acidosis close to normal, but never quite gets to the normal value. The effects become very weak as plasma

Renal Buffering The fine adjustment to plasma p. H is done by the kidneys. Recall that H+ is actively secreted in the nephron, bicarbonate (HCO 3 -) is actively reabsorbed. The rate at which these things happen depend entirely on plasma p. H. The renal system is relatively slow, of moderate capacity, but extremely precise. When plasma p. H is acidotic or alkalotic, chemical buffers make extremely rapid adjustments but have very limited capacity. Respiratory system rapidly brings the p. H close to, but not quite normal. Renal adjustment over the course of several hours to a day restore normal p. H.

Types of Acid-Base Imbalances 1. Respiratory imbalances. These result from inappropriate rates of exchange of CO 2 with air. Hypoventilation -> respiratory acidosis Hyperventilation -> respiratory alkalosis Pulmonary disorders (asthma, pneumonia) can cause respiratory acidosis. 2. Metabolic imbalances. Any acid-base imbalance not resulting from respiratory system is metabolic. Diarrhea causes loss of alkaline fluid, resulting in metabolic acidosis. Vomiting causes loss of acidic fluid, resulting in metabolic alkalosis. Vomiting and diarrhea also cause water imbalances, another reason why they’re dangerous.

- Slides: 16