First Law of Thermodynamics Doba Jackson Ph D

First Law of Thermodynamics Doba Jackson, Ph. D. Dept of Chemistry & Biochemistry Huntingdon College

Outline of Chapter 2 • • Basic Concepts: Heat, Work, Energy First Law of Thermodynamics Expansion work Measurement of Heat Enthalpy changes Adiabatic changes (Cooling) Thermochemistry Inexact Differntials

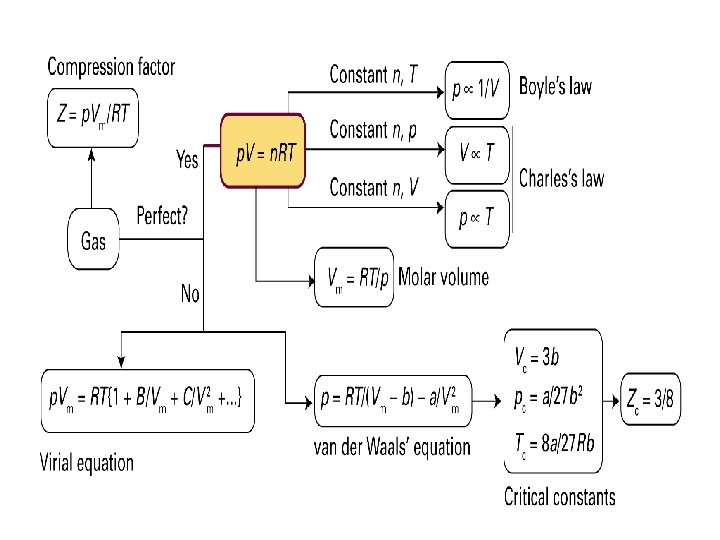

System, Surroundings, Universe • System- Part of the world of interest • Surroundings- Region outside the system • Open system- Allows matter and energy to pass • Closed system- Cannot allow matter to pass • Isolated system- Cannot allow matter or energy to pass

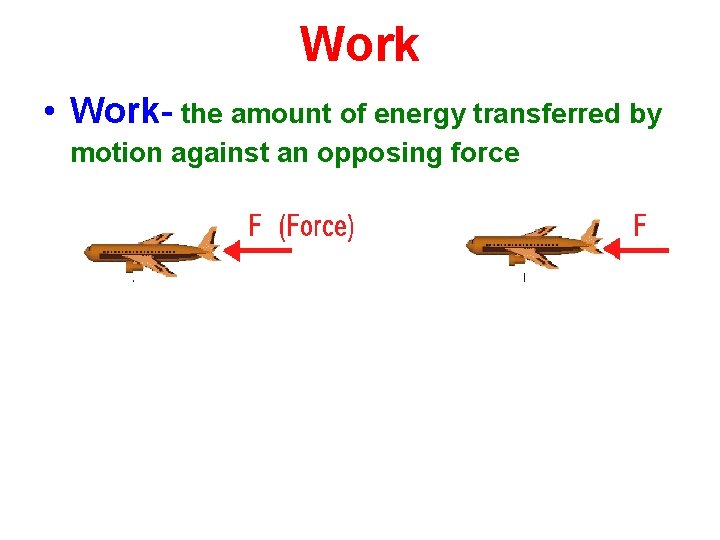

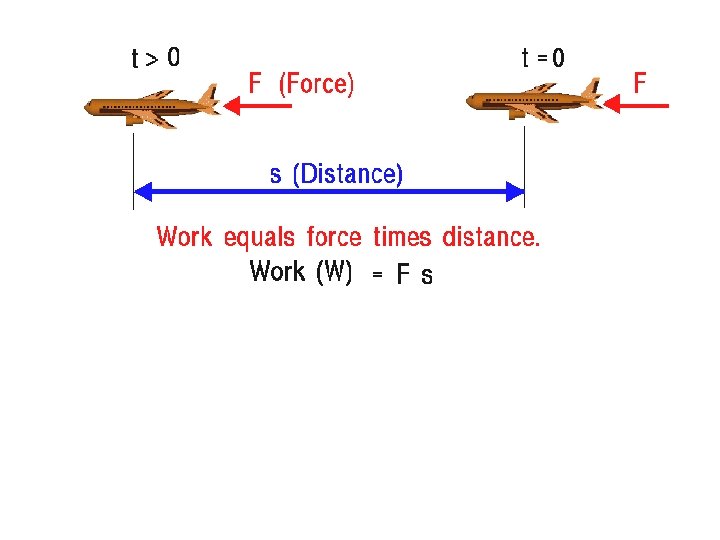

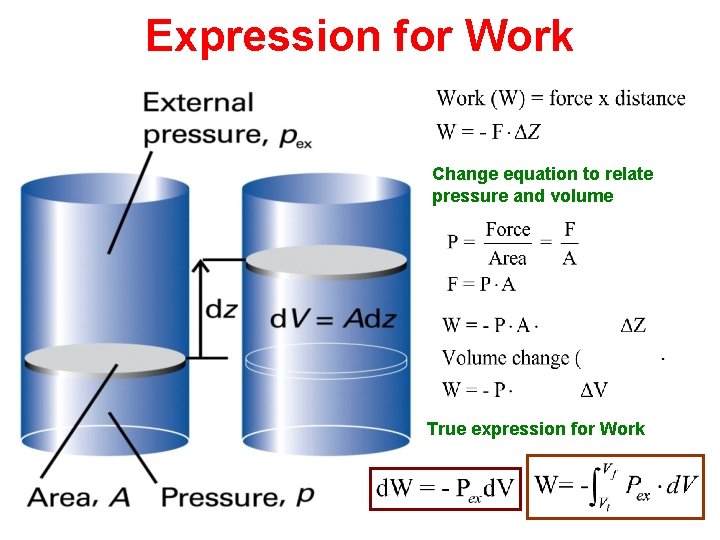

Work • Work- the amount of energy transferred by motion against an opposing force ▪

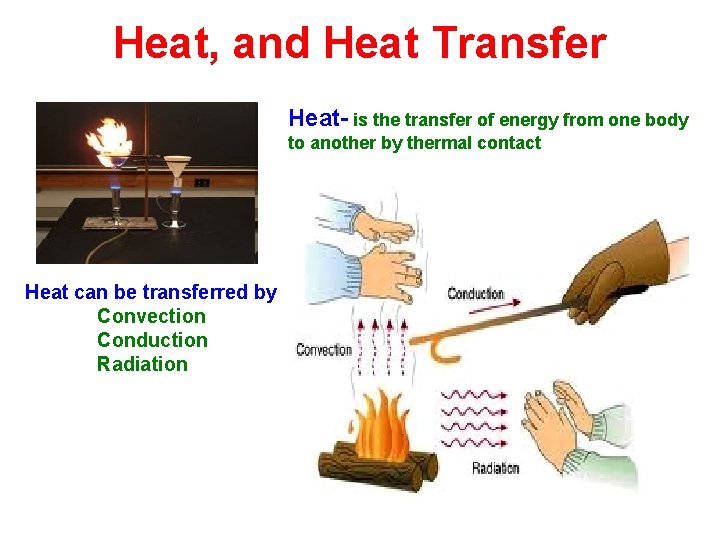

Heat, and Heat Transfer Heat- is the transfer of energy from one body to another by thermal contact Heat can be transferred by Convection Conduction Radiation

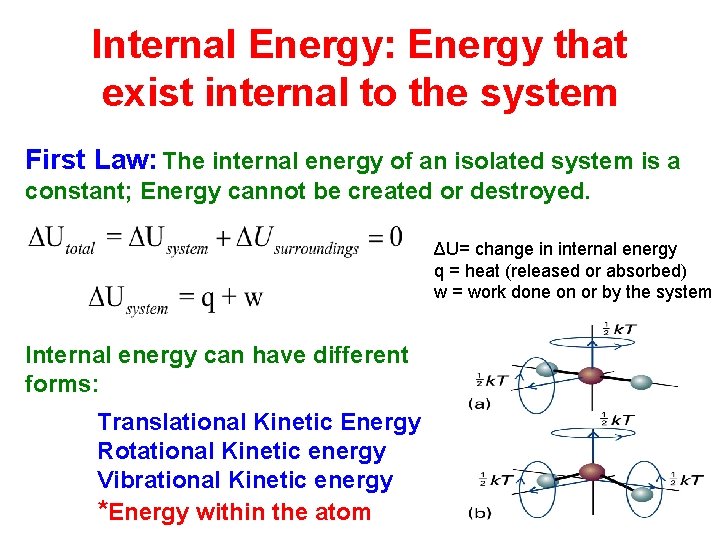

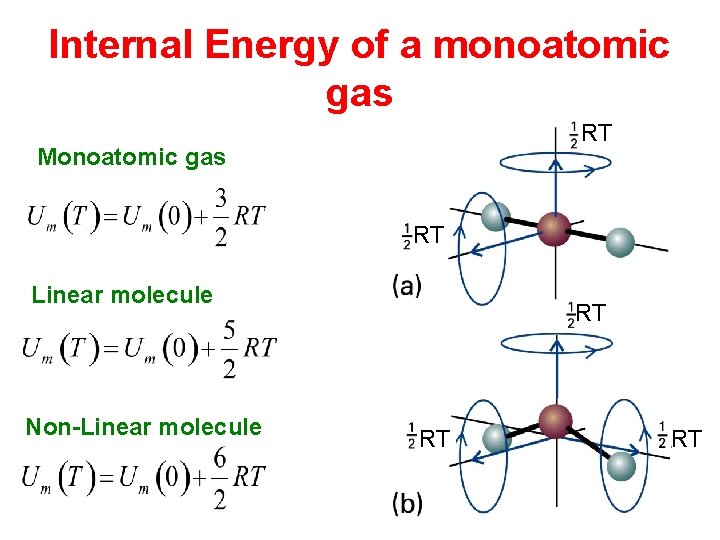

Internal Energy: Energy that exist internal to the system First Law: The internal energy of an isolated system is a constant; Energy cannot be created or destroyed. ΔU= change in internal energy q = heat (released or absorbed) w = work done on or by the system Internal energy can have different forms: Translational Kinetic Energy Rotational Kinetic energy Vibrational Kinetic energy *Energy within the atom

Internal Energy of a monoatomic gas RT Monoatomic gas RT Linear molecule Non-Linear molecule RT RT RT

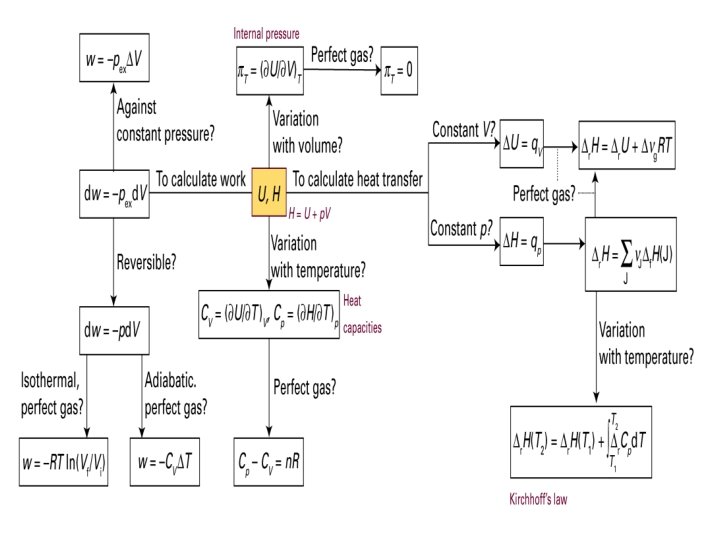

Expression for Work Change equation to relate pressure and volume True expression for Work

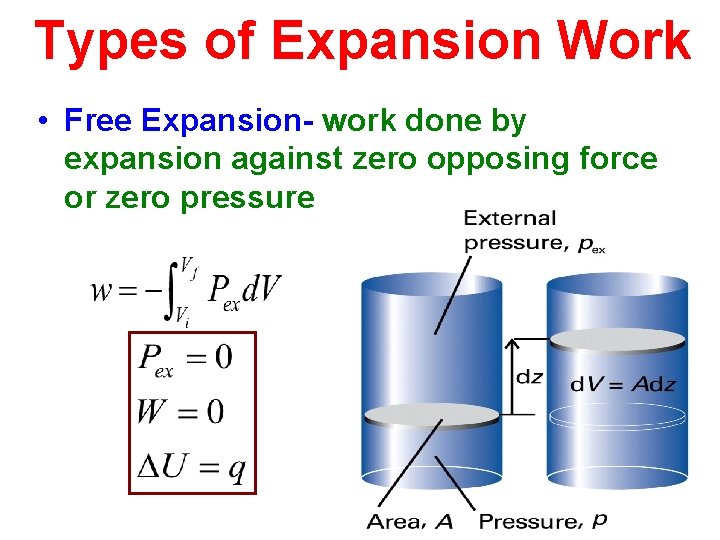

Types of Expansion Work • Free Expansion- work done by expansion against zero opposing force or zero pressure

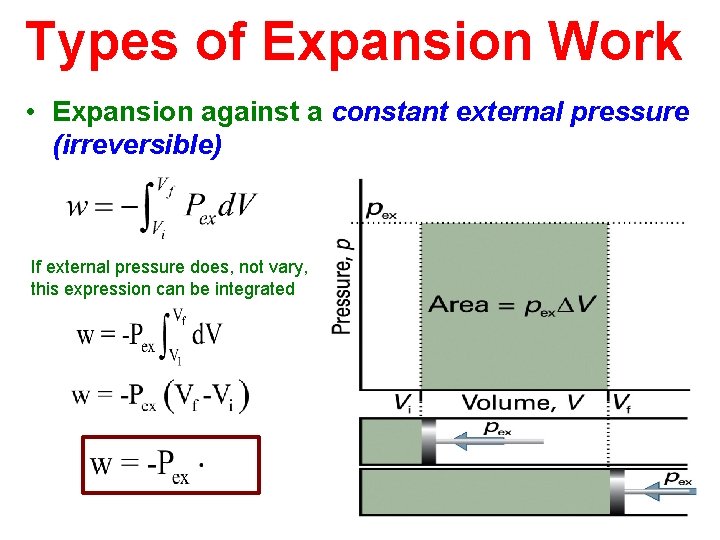

Types of Expansion Work • Expansion against a constant external pressure (irreversible) If external pressure does, not vary, this expression can be integrated

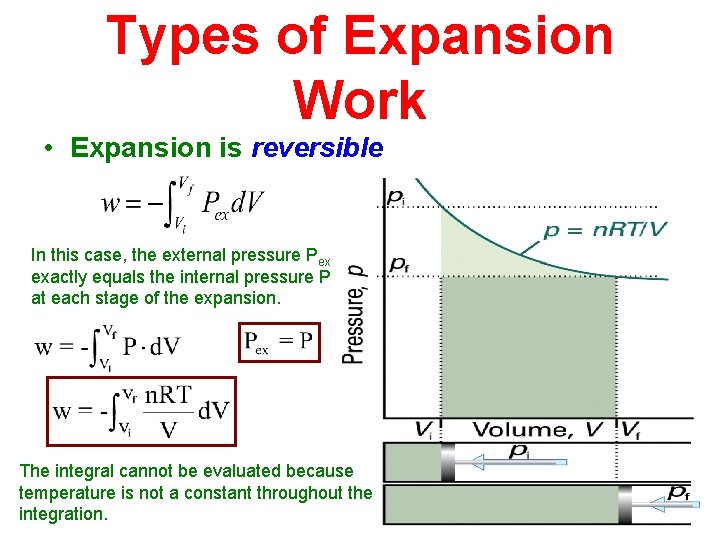

Types of Expansion Work • Expansion is reversible In this case, the external pressure Pex exactly equals the internal pressure P at each stage of the expansion. The integral cannot be evaluated because temperature is not a constant throughout the integration.

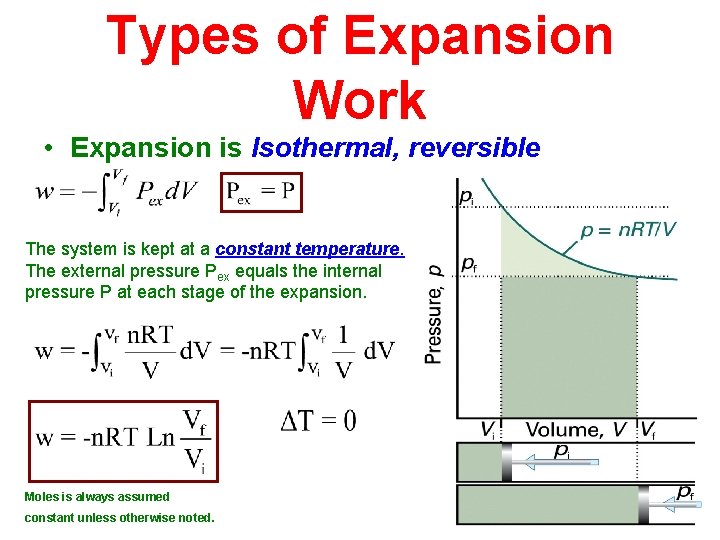

Types of Expansion Work • Expansion is Isothermal, reversible The system is kept at a constant temperature. The external pressure Pex equals the internal pressure P at each stage of the expansion. Moles is always assumed constant unless otherwise noted.

Problems: Calculate the work needed for a 65 kg person to climb up 4. 0 meters on (a) the earth, (b) the moon (g=1. 60 m/s 2)

Problem 1: A chemical reaction takes place in a container of cross sectional area of 50. 0 cm 2. As a result of the reaction, a piston is pushed out through 15 cm against an constant external pressure of 121 k. Pa. Calculate the work (in Joules) done by the system

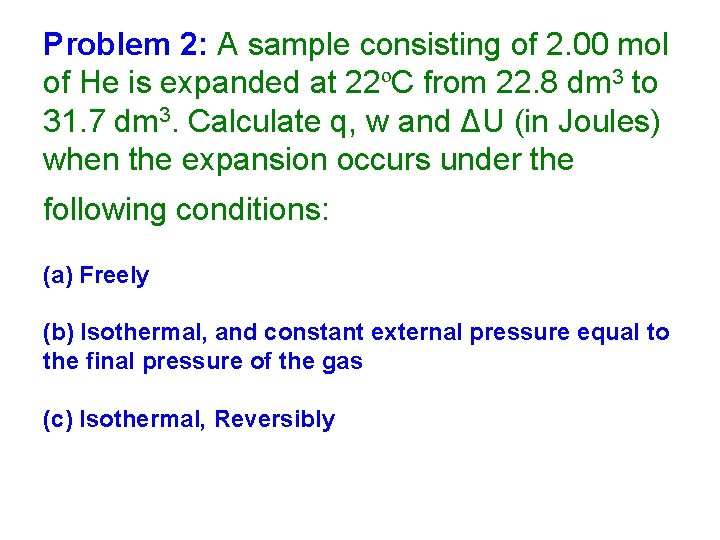

Problem 2: A sample consisting of 2. 00 mol of He is expanded at 22ºC from 22. 8 dm 3 to 31. 7 dm 3. Calculate q, w and ΔU (in Joules) when the expansion occurs under the following conditions: (a) Freely (b) Isothermal, and constant external pressure equal to the final pressure of the gas (c) Isothermal, Reversibly

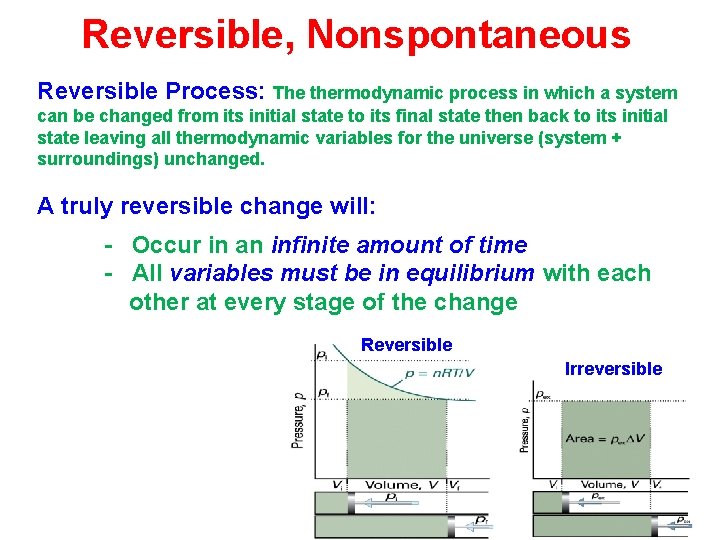

Reversible, Nonspontaneous Reversible Process: The thermodynamic process in which a system can be changed from its initial state to its final state then back to its initial state leaving all thermodynamic variables for the universe (system + surroundings) unchanged. A truly reversible change will: - Occur in an infinite amount of time - All variables must be in equilibrium with each other at every stage of the change Reversible Irreversible

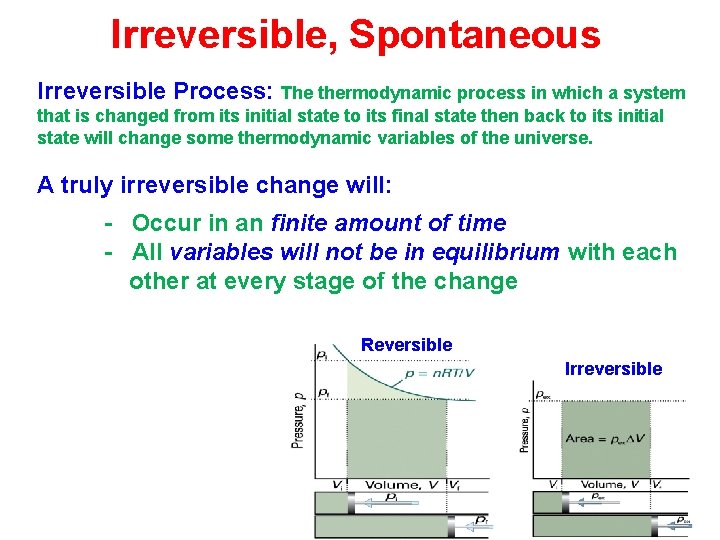

Irreversible, Spontaneous Irreversible Process: The thermodynamic process in which a system that is changed from its initial state to its final state then back to its initial state will change some thermodynamic variables of the universe. A truly irreversible change will: - Occur in an finite amount of time - All variables will not be in equilibrium with each other at every stage of the change Reversible Irreversible

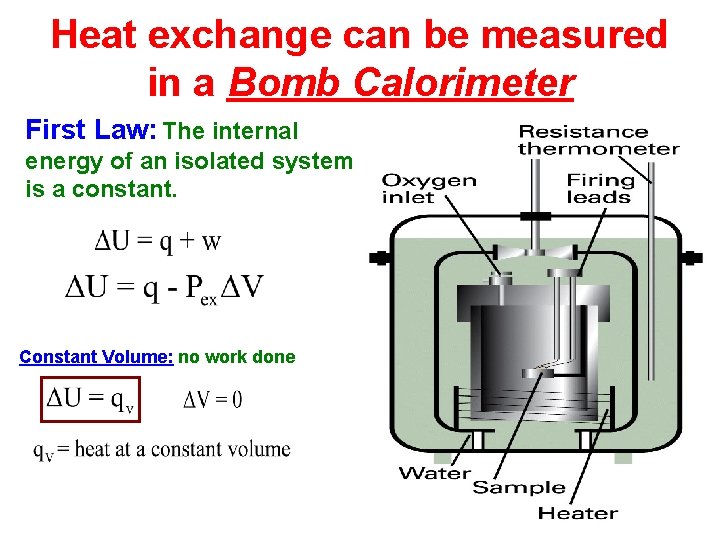

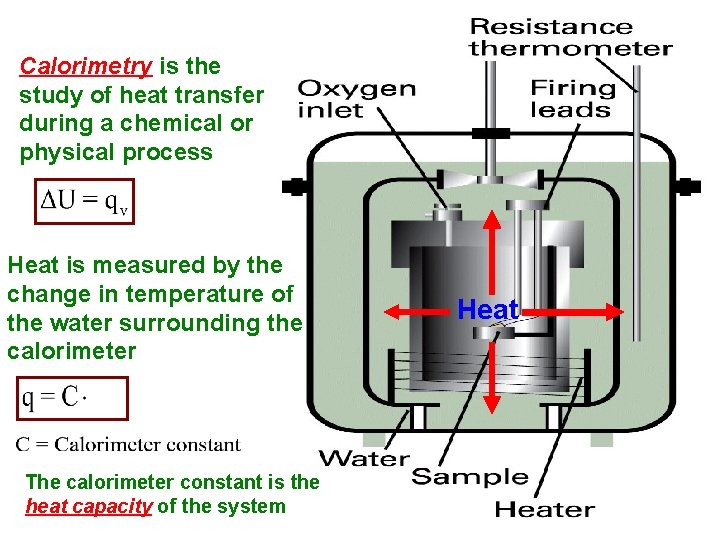

Heat exchange can be measured in a Bomb Calorimeter First Law: The internal energy of an isolated system is a constant. Constant Volume: no work done

Calorimetry is the study of heat transfer during a chemical or physical process Heat is measured by the change in temperature of the water surrounding the calorimeter The calorimeter constant is the heat capacity of the system Heat

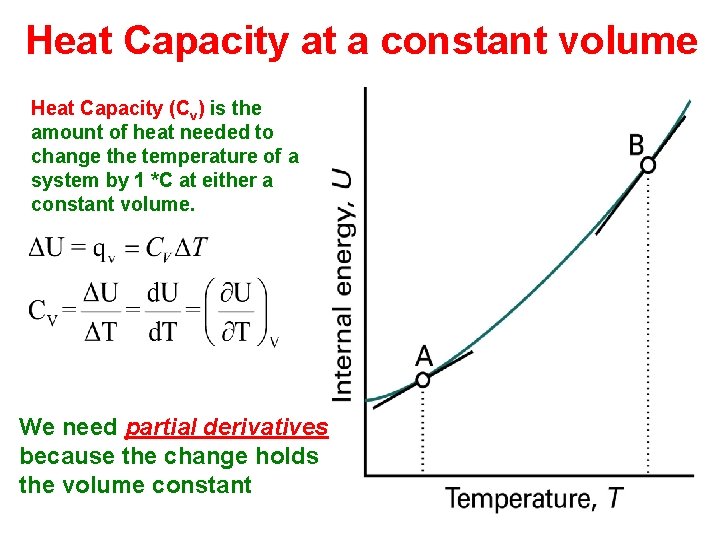

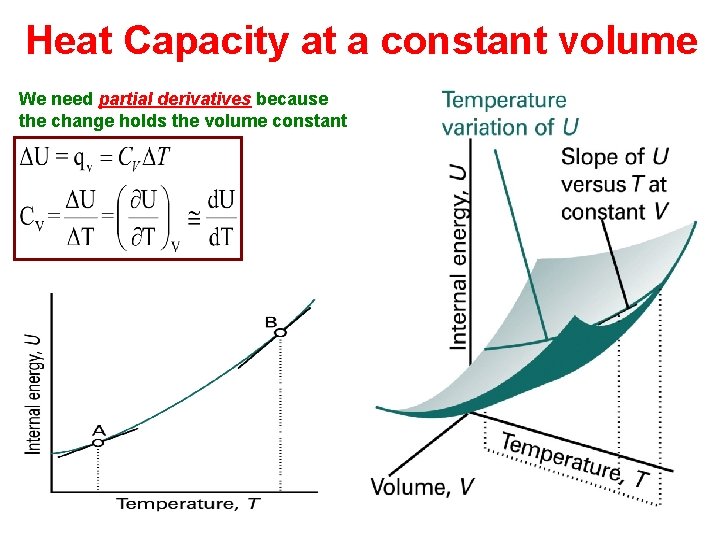

Heat Capacity at a constant volume Heat Capacity (Cv) is the amount of heat needed to change the temperature of a system by 1 *C at either a constant volume. We need partial derivatives because the change holds the volume constant

Heat Capacity at a constant volume We need partial derivatives because the change holds the volume constant

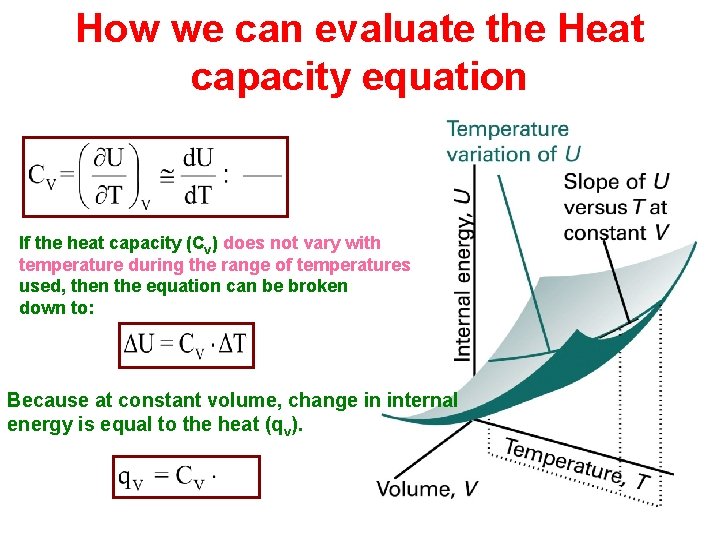

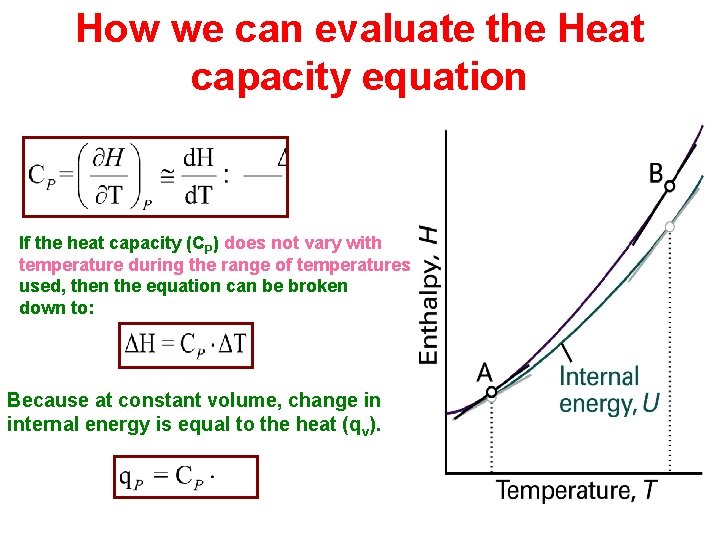

How we can evaluate the Heat capacity equation If the heat capacity (Cv) does not vary with temperature during the range of temperatures used, then the equation can be broken down to: Because at constant volume, change in internal energy is equal to the heat (qv).

Problem 2. 4: A sample consisting of 1. 00 mol of a perfect gas, for which Cv, m = (3/2)R, initially at P = 1. 00 atm and T = 300 K, is heated reversibly to 400 K at a constant volume. Calculate the final pressure, ΔU, q, and w

We cannot measure internal energy when the volume is not constant Typical reactions occur a constant external pressure

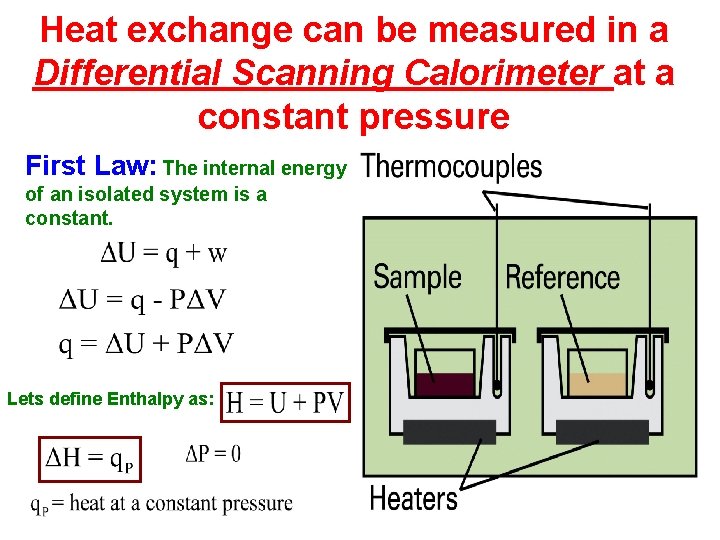

Heat exchange can be measured in a Differential Scanning Calorimeter at a constant pressure First Law: The internal energy of an isolated system is a constant. Lets define Enthalpy as:

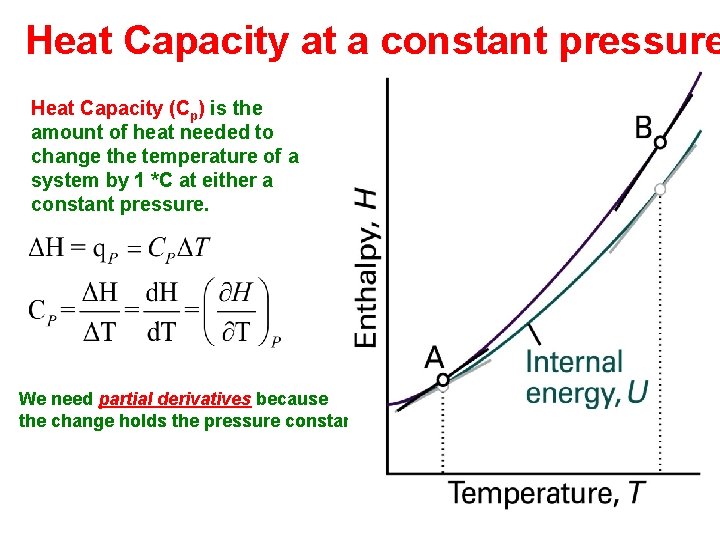

Heat Capacity at a constant pressure Heat Capacity (Cp) is the amount of heat needed to change the temperature of a system by 1 *C at either a constant pressure. We need partial derivatives because the change holds the pressure constant

How we can evaluate the Heat capacity equation If the heat capacity (CP) does not vary with temperature during the range of temperatures used, then the equation can be broken down to: Because at constant volume, change in internal energy is equal to the heat (qv).

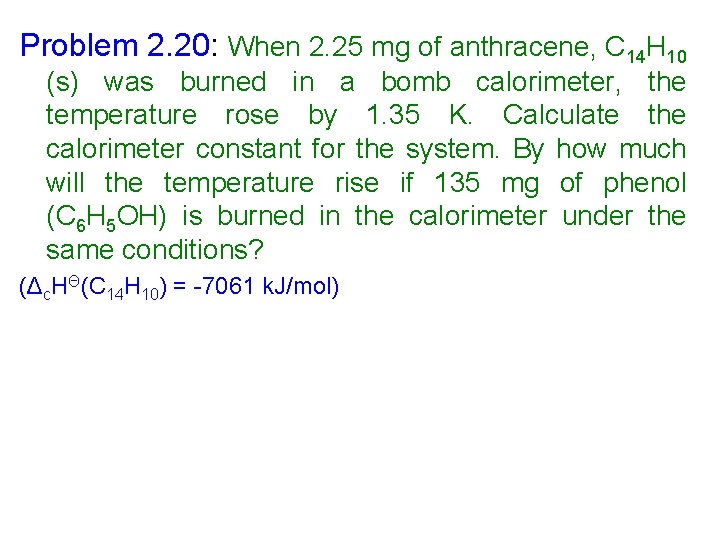

Problem 2. 20: When 2. 25 mg of anthracene, C 14 H 10 (s) was burned in a bomb calorimeter, the temperature rose by 1. 35 K. Calculate the calorimeter constant for the system. By how much will the temperature rise if 135 mg of phenol (C 6 H 5 OH) is burned in the calorimeter under the same conditions? (Δc. HΘ(C 14 H 10) = -7061 k. J/mol)

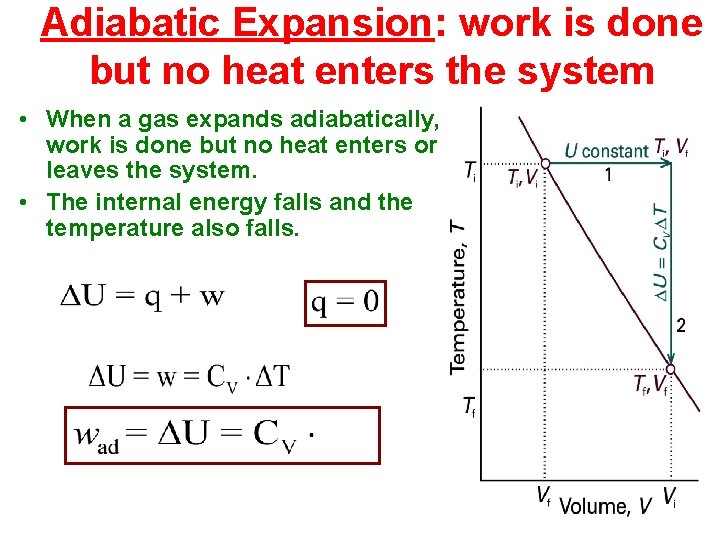

Adiabatic Expansion: work is done but no heat enters the system • When a gas expands adiabatically, work is done but no heat enters or leaves the system. • The internal energy falls and the temperature also falls.

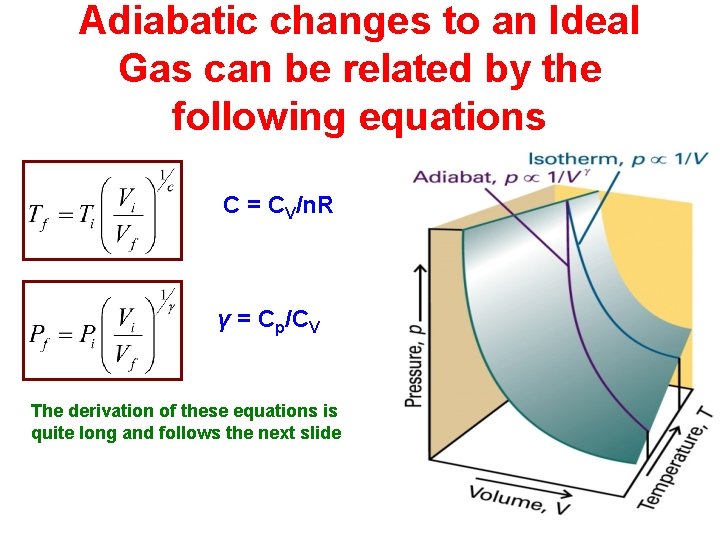

Adiabatic changes to an Ideal Gas can be related by the following equations C = CV/n. R γ = Cp/CV The derivation of these equations is quite long and follows the next slide

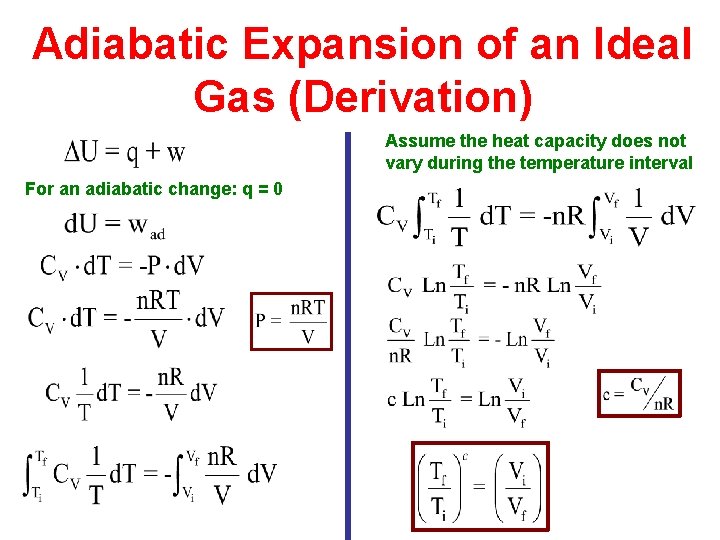

Adiabatic Expansion of an Ideal Gas (Derivation) Assume the heat capacity does not vary during the temperature interval For an adiabatic change: q = 0

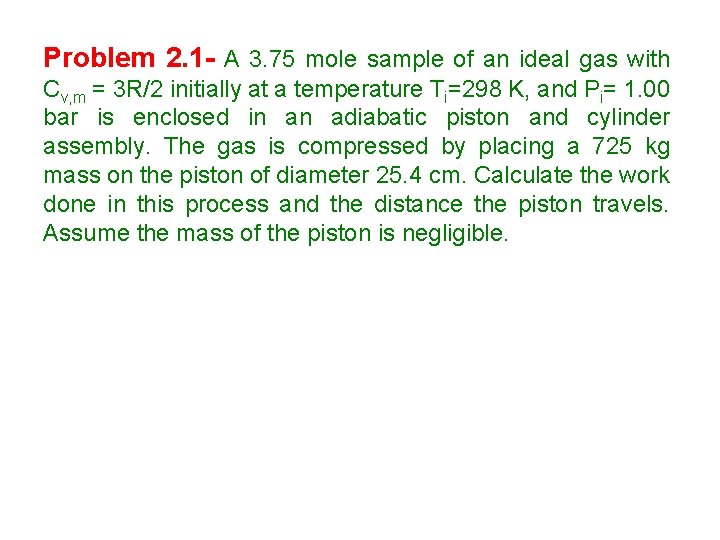

Problem 2. 1 - A 3. 75 mole sample of an ideal gas with Cv, m = 3 R/2 initially at a temperature Ti=298 K, and Pi= 1. 00 bar is enclosed in an adiabatic piston and cylinder assembly. The gas is compressed by placing a 725 kg mass on the piston of diameter 25. 4 cm. Calculate the work done in this process and the distance the piston travels. Assume the mass of the piston is negligible.

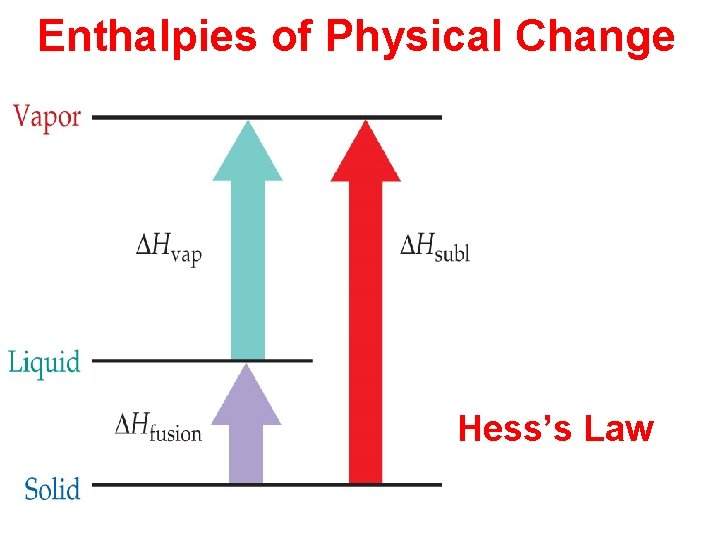

Thermochemistry The study of energy transferred as heat during the course of chemical reactions. In thermochemistry, we rely on calorimetry to measure the internal energy (∆U) enthalpy (∆H). Changes in matter are: Physical Changes Solid Liquid Melting (Fusion) Liquid Gas Boiling (Vaporization) Solid Gas Sublimation Chemical Changes Formation reactions Combustion reactions Other reactions

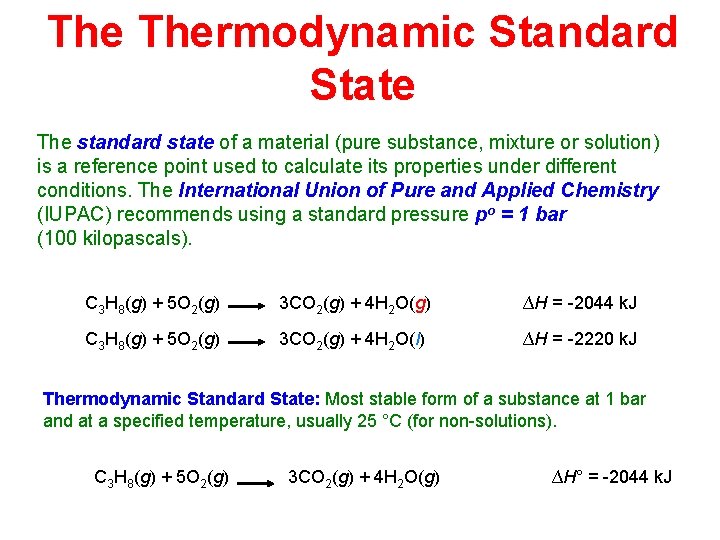

The Thermodynamic Standard State The standard state of a material (pure substance, mixture or solution) is a reference point used to calculate its properties under different conditions. The International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC) recommends using a standard pressure po = 1 bar (100 kilopascals). C 3 H 8(g) + 5 O 2(g) 3 CO 2(g) + 4 H 2 O(g) ∆H = -2044 k. J C 3 H 8(g) + 5 O 2(g) 3 CO 2(g) + 4 H 2 O(l) ∆H = -2220 k. J Thermodynamic Standard State: Most stable form of a substance at 1 bar and at a specified temperature, usually 25 °C (for non-solutions). C 3 H 8(g) + 5 O 2(g) 3 CO 2(g) + 4 H 2 O(g) ∆H° = -2044 k. J

Physical and Chemical Transitions

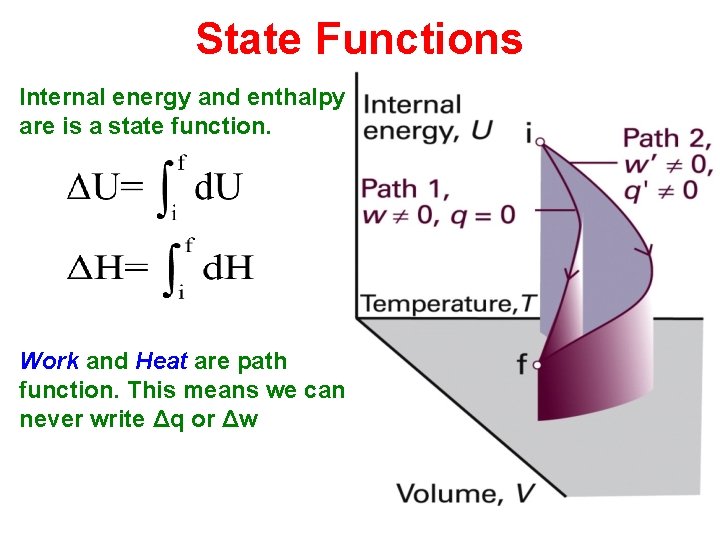

State Functions Internal energy and enthalpy are is a state function. Work and Heat are path function. This means we can never write Δq or Δw

Enthalpies of Physical Change Hess’s Law

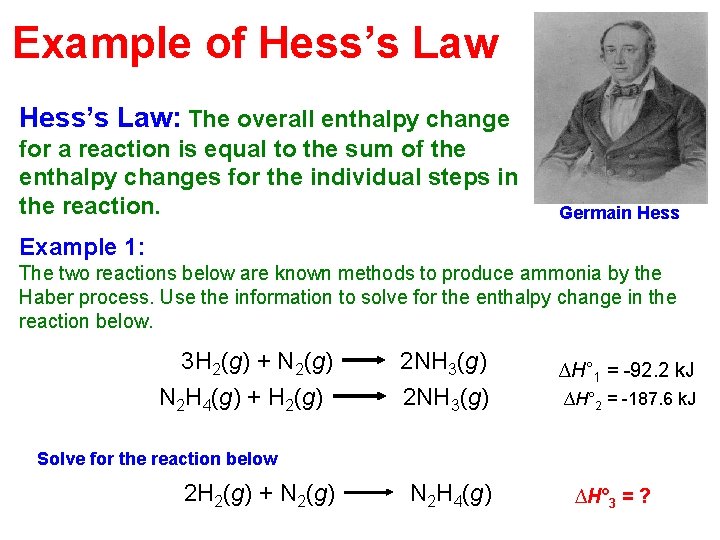

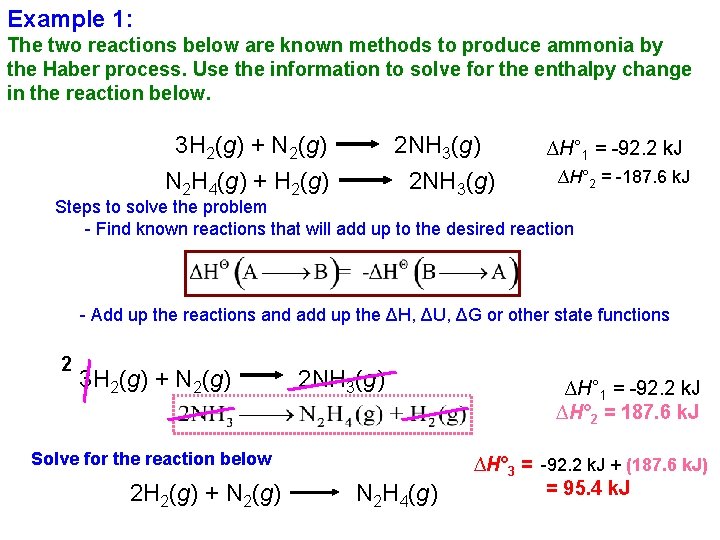

Example of Hess’s Law: The overall enthalpy change for a reaction is equal to the sum of the enthalpy changes for the individual steps in the reaction. Germain Hess Example 1: The two reactions below are known methods to produce ammonia by the Haber process. Use the information to solve for the enthalpy change in the reaction below. 3 H 2(g) + N 2(g) N 2 H 4(g) + H 2(g) 2 NH 3(g) ∆H° 1 = -92. 2 k. J ∆H° 2 = -187. 6 k. J Solve for the reaction below 2 H 2(g) + N 2(g) N 2 H 4(g) ∆H° 3 = ?

Example 1: The two reactions below are known methods to produce ammonia by the Haber process. Use the information to solve for the enthalpy change in the reaction below. 3 H 2(g) + N 2(g) N 2 H 4(g) + H 2(g) 2 NH 3(g) ∆H° 1 = -92. 2 k. J ∆H° 2 = -187. 6 k. J Steps to solve the problem - Find known reactions that will add up to the desired reaction - Add up the reactions and add up the ΔH, ΔU, ΔG or other state functions 2 3 H 2(g) + N 2(g) 2 NH 3(g) Solve for the reaction below 2 H 2(g) + N 2(g) N 2 H 4(g) ∆H° 1 = -92. 2 k. J ∆H° 2 = 187. 6 k. J ∆H° 3 = -92. 2 k. J + (187. 6 k. J) = 95. 4 k. J

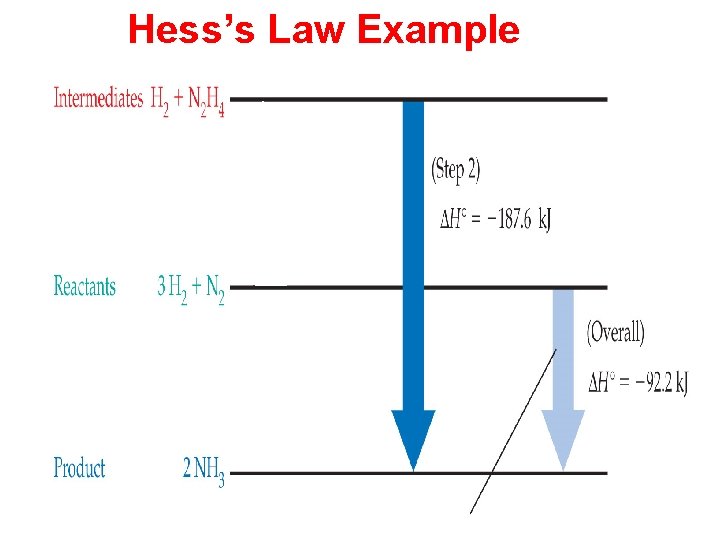

Hess’s Law Example

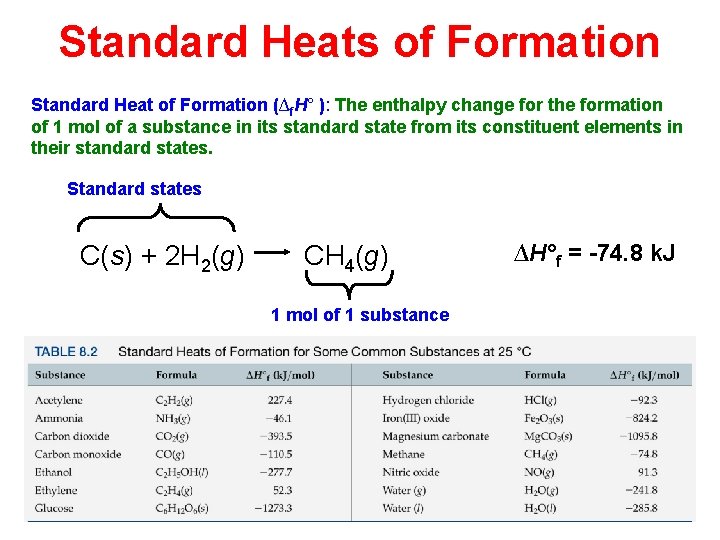

Standard Heats of Formation Standard Heat of Formation (∆f. H° ): The enthalpy change for the formation of 1 mol of a substance in its standard state from its constituent elements in their standard states. Standard states C(s) + 2 H 2(g) CH 4(g) 1 mol of 1 substance ∆H°f = -74. 8 k. J

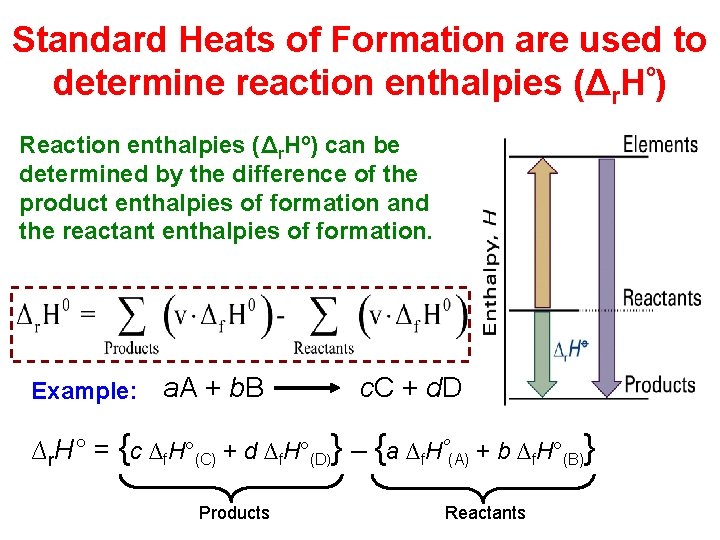

Standard Heats of Formation are used to determine reaction enthalpies (Δr. Hº) Reaction enthalpies (Δr. Hº) can be determined by the difference of the product enthalpies of formation and the reactant enthalpies of formation. Example: a. A + b. B c. C + d. D ∆r. H° = {c ∆f. H°(C) + d ∆f. H°(D)} – {a ∆f. Hº(A) + b ∆f. H°(B)} Products Reactants

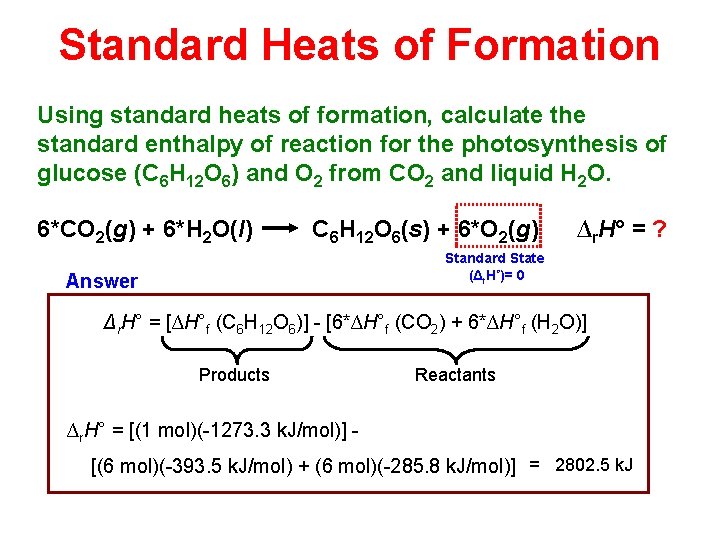

Standard Heats of Formation Using standard heats of formation, calculate the standard enthalpy of reaction for the photosynthesis of glucose (C 6 H 12 O 6) and O 2 from CO 2 and liquid H 2 O. 6*CO 2(g) + 6*H 2 O(l) C 6 H 12 O 6(s) + 6*O 2(g) ∆r. H° = ? Standard State (Δf. Hº)= 0 Answer Δr. H° = [∆H°f (C 6 H 12 O 6)] - [6*∆H°f (CO 2) + 6*∆H°f (H 2 O)] Products Reactants ∆r. H° = [(1 mol)(-1273. 3 k. J/mol)] [(6 mol)(-393. 5 k. J/mol) + (6 mol)(-285. 8 k. J/mol)] = 2802. 5 k. J

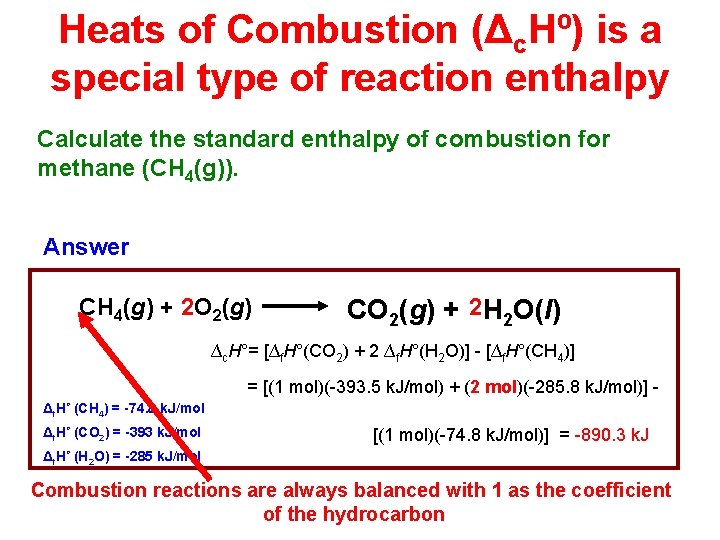

Heats of Combustion (Δc. Hº) is a special type of reaction enthalpy Calculate the standard enthalpy of combustion for methane (CH 4(g)). Answer CH 4(g) + 2 O 2(g) CO 2(g) + 2 H 2 O(l) ∆c. H°= [∆f. H°(CO 2) + 2 ∆f. H°(H 2 O)] - [∆f. H°(CH 4)] = [(1 mol)(-393. 5 k. J/mol) + (2 mol)(-285. 8 k. J/mol)] Δf. Hº (CH 4) = -74. 8 k. J/mol Δf. Hº (CO 2) = -393 k. J/mol [(1 mol)(-74. 8 k. J/mol)] = -890. 3 k. J Δf. Hº (H 2 O) = -285 k. J/mol Combustion reactions are always balanced with 1 as the coefficient of the hydrocarbon

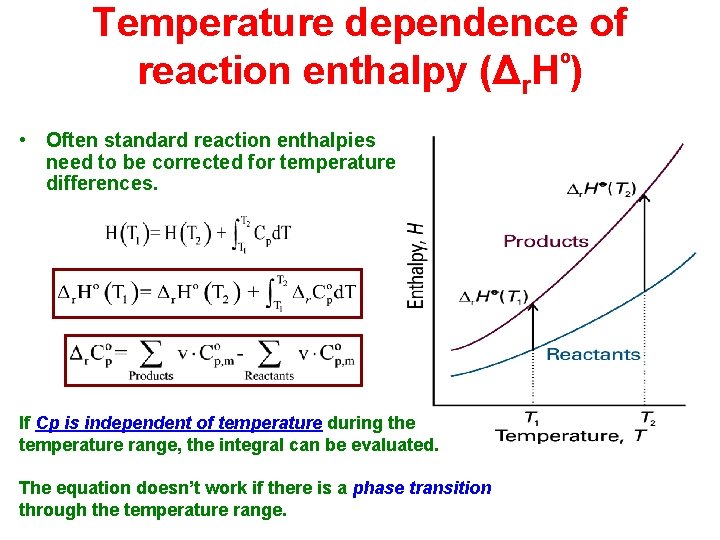

Temperature dependence of reaction enthalpy (Δr. Hº) • Often standard reaction enthalpies need to be corrected for temperature differences. If Cp is independent of temperature during the temperature range, the integral can be evaluated. The equation doesn’t work if there is a phase transition through the temperature range.

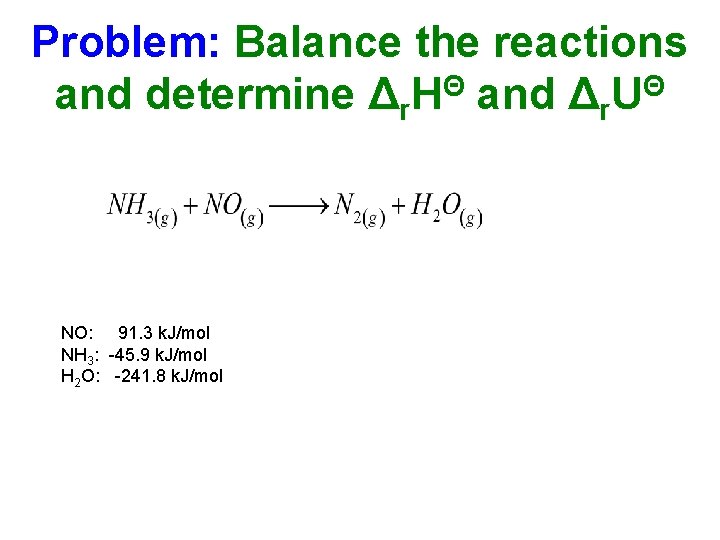

Problem: Balance the reactions and determine Δr. HΘ and Δr. UΘ NO: 91. 3 k. J/mol NH 3: -45. 9 k. J/mol H 2 O: -241. 8 k. J/mol

- Slides: 50