Finite Element Simulation of Woven Fabric Composites B

Finite Element Simulation of Woven Fabric Composites B. H. Le Page*, F. J. Guild+, S. L. Ogin* and P. A. Smith* *School of Engineering, University of Surrey, UK +Department of Mechanical Engineering, University of Bristol, UK Collaborative project supported by EPSRC University of Bristol

Introduction • Woven fabric composites - why modelling? • Development of the models – Modelling approach – Layer/phase shift • Predictions of Stiffness – Compliance calculation • Predictions of energy release rate for cracks • Comparison of results – Effect of layer/phase shift – Comparison with equivalent cross-ply laminates • Conclusions University of Bristol

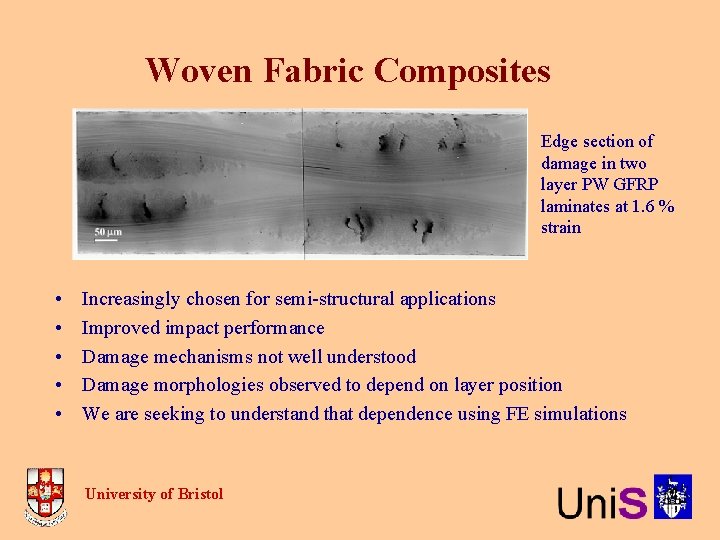

Woven Fabric Composites Edge section of damage in two layer PW GFRP laminates at 1. 6 % strain • • • Increasingly chosen for semi-structural applications Improved impact performance Damage mechanisms not well understood Damage morphologies observed to depend on layer position We are seeking to understand that dependence using FE simulations University of Bristol

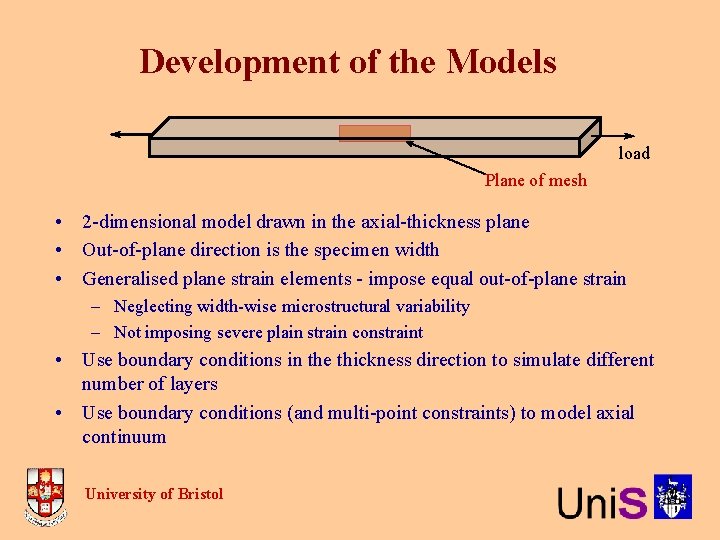

Development of the Models load Plane of mesh • 2 -dimensional model drawn in the axial-thickness plane • Out-of-plane direction is the specimen width • Generalised plane strain elements - impose equal out-of-plane strain – Neglecting width-wise microstructural variability – Not imposing severe plain strain constraint • Use boundary conditions in the thickness direction to simulate different number of layers • Use boundary conditions (and multi-point constraints) to model axial continuum University of Bristol

Development of the Mesh Micrograph Longitudinal tow Model • • • The modelled shape of the fibre tow was matched to microstructural measurements The tow shape was found to be sinusoidal All the meshes were developed from this half-wave of the tow University of Bristol

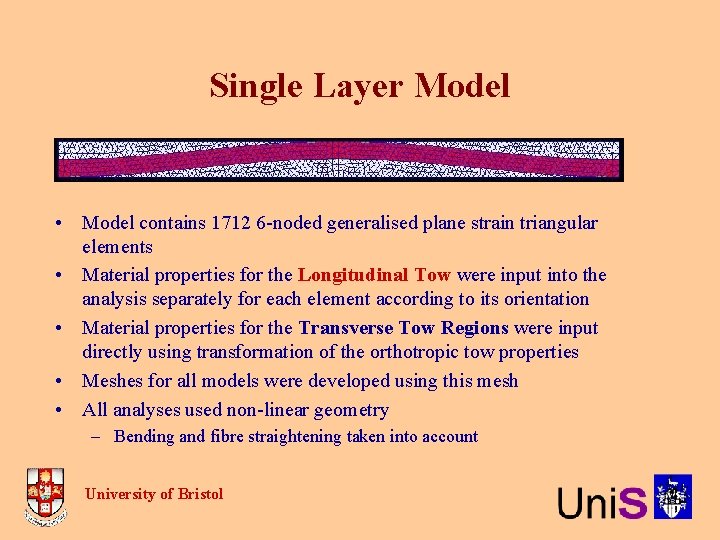

Single Layer Model • Model contains 1712 6 -noded generalised plane strain triangular elements • Material properties for the Longitudinal Tow were input into the analysis separately for each element according to its orientation • Material properties for the Transverse Tow Regions were input directly using transformation of the orthotropic tow properties • Meshes for all models were developed using this mesh • All analyses used non-linear geometry – Bending and fibre straightening taken into account University of Bristol

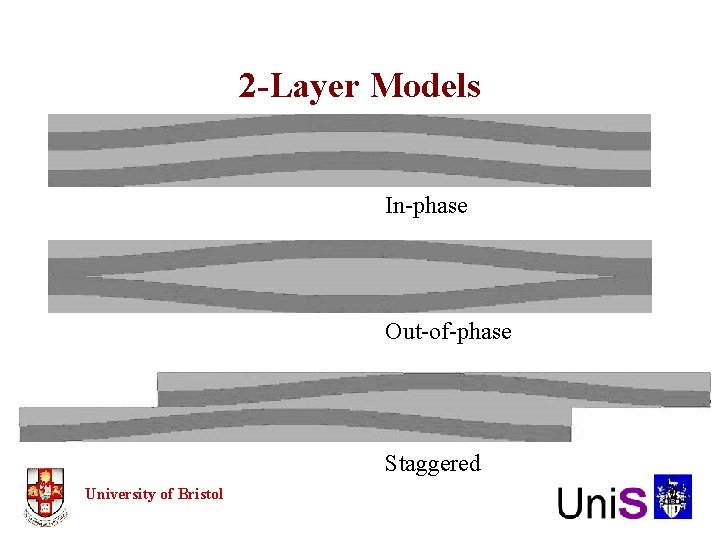

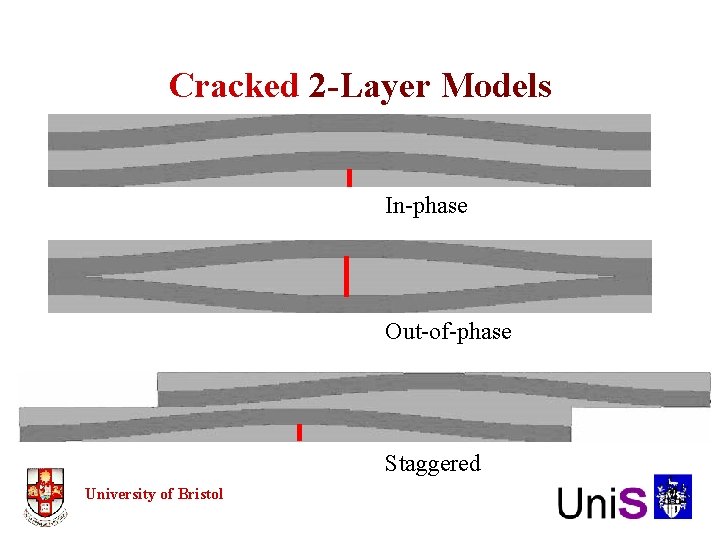

2 -Layer Models In-phase Out-of-phase Staggered University of Bristol

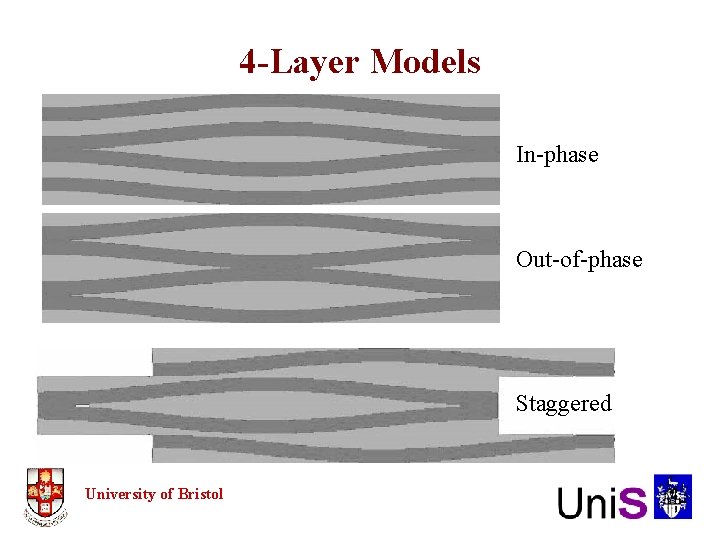

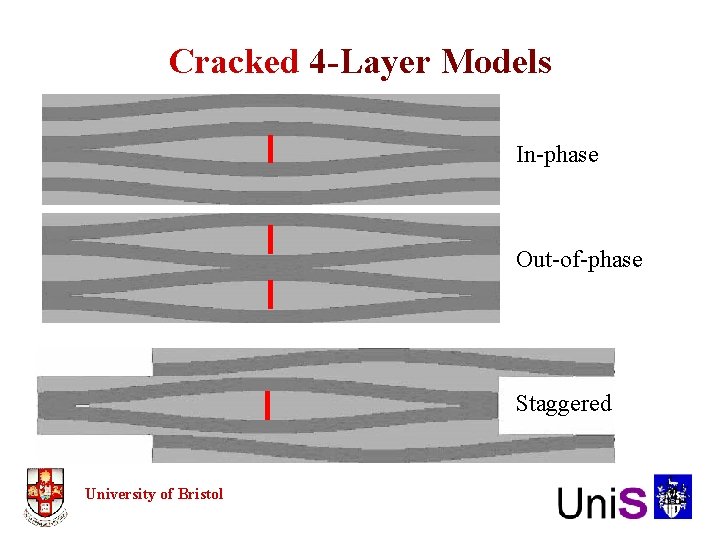

4 -Layer Models In-phase Out-of-phase Staggered University of Bristol

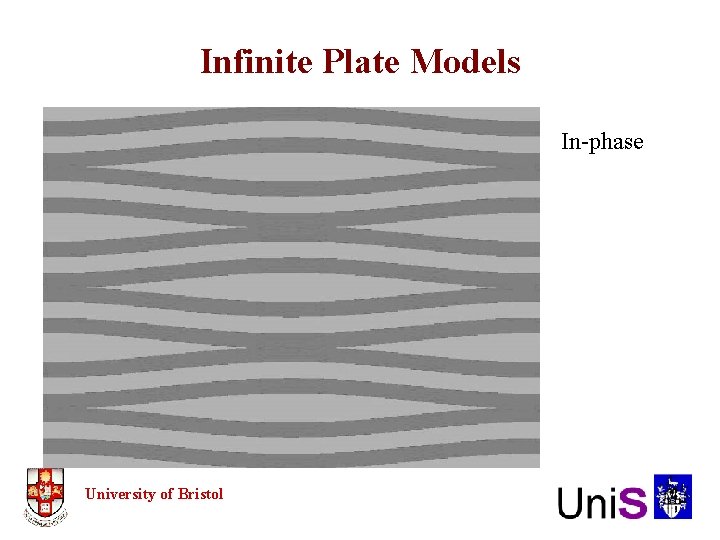

Infinite Plate Models In-phase University of Bristol

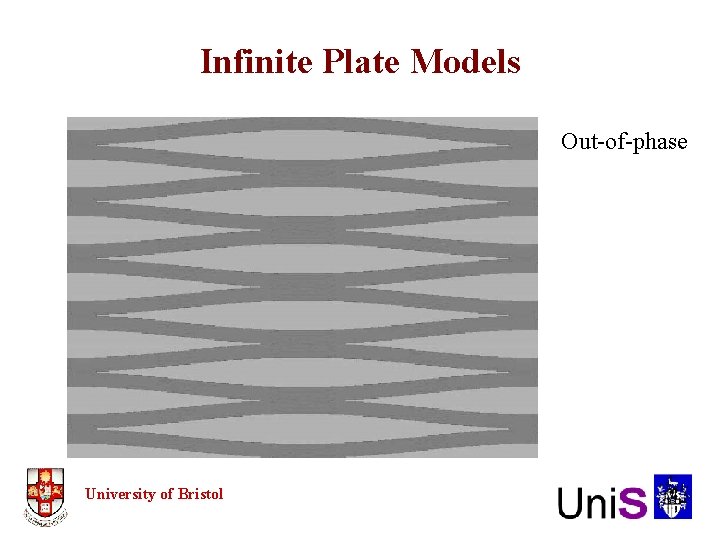

Infinite Plate Models Out-of-phase University of Bristol

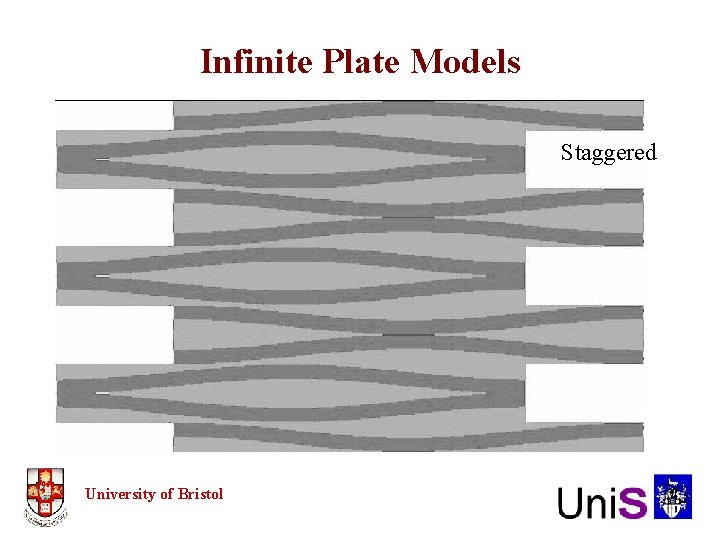

Infinite Plate Models Staggered University of Bristol

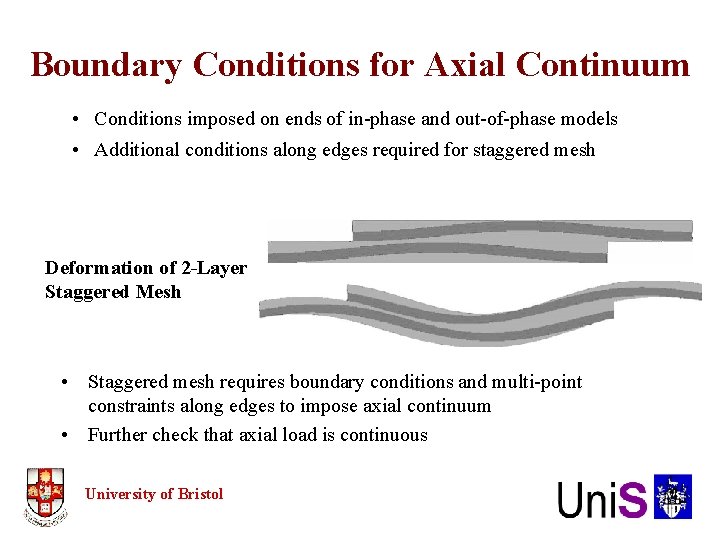

Boundary Conditions for Axial Continuum • Conditions imposed on ends of in-phase and out-of-phase models • Additional conditions along edges required for staggered mesh Deformation of 2 -Layer Staggered Mesh • Staggered mesh requires boundary conditions and multi-point constraints along edges to impose axial continuum • Further check that axial load is continuous University of Bristol

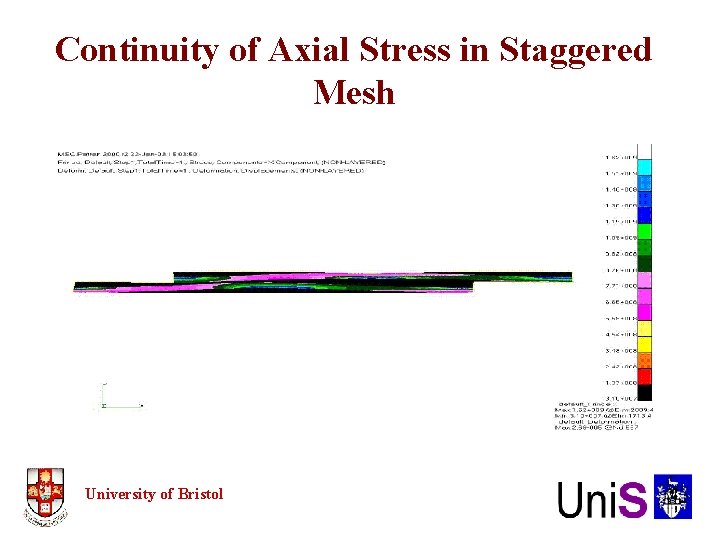

Continuity of Axial Stress in Staggered Mesh University of Bristol

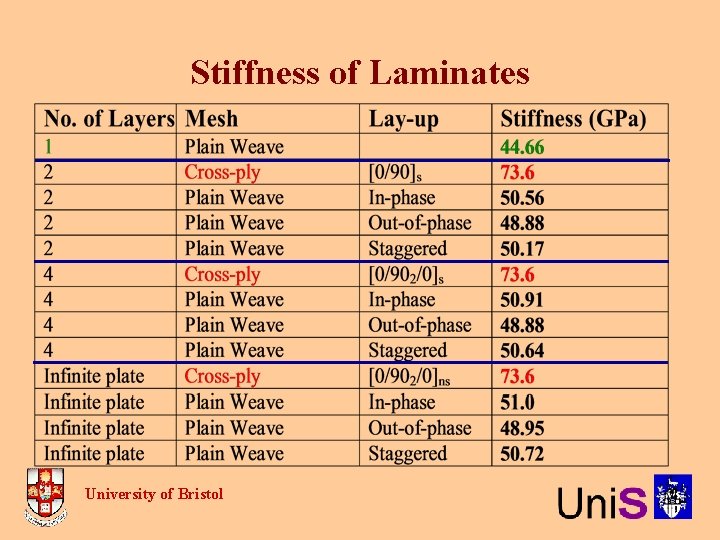

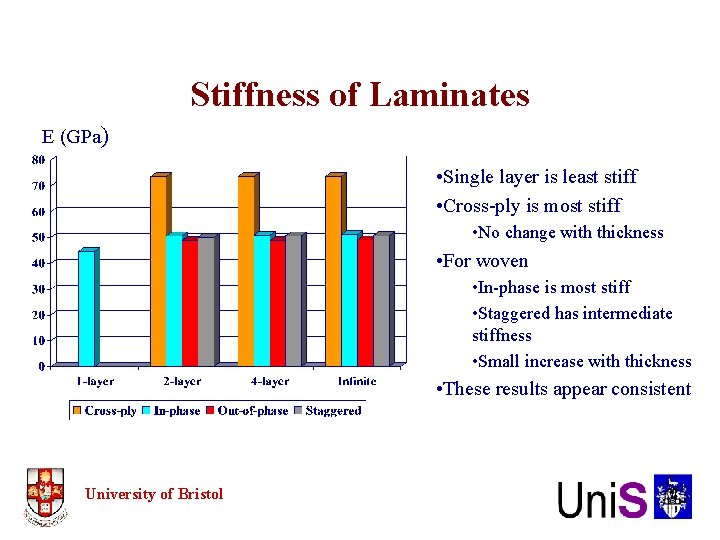

Stiffness of Laminates University of Bristol

Stiffness of Laminates E (GPa) • Single layer is least stiff • Cross-ply is most stiff • No change with thickness • For woven • In-phase is most stiff • Staggered has intermediate stiffness • Small increase with thickness • These results appear consistent University of Bristol

Cracked 2 -Layer Models In-phase Out-of-phase Staggered University of Bristol

Cracked 4 -Layer Models In-phase Out-of-phase Staggered University of Bristol

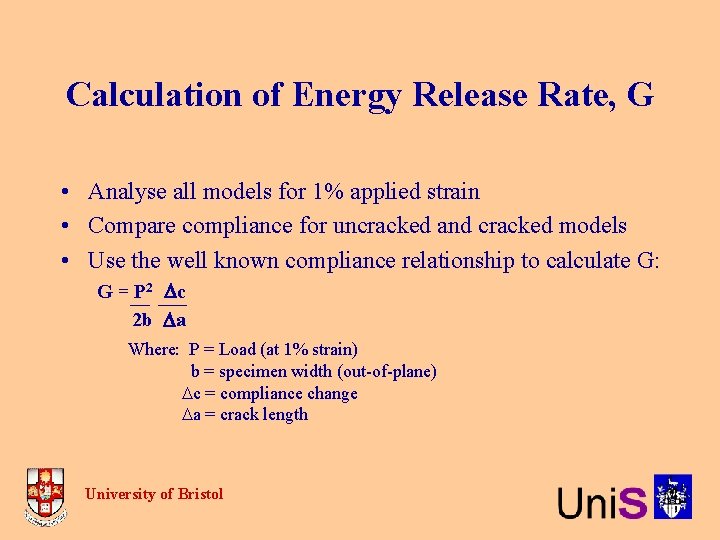

Calculation of Energy Release Rate, G • Analyse all models for 1% applied strain • Compare compliance for uncracked and cracked models • Use the well known compliance relationship to calculate G: G = P 2 c 2 b a Where: P = Load (at 1% strain) b = specimen width (out-of-plane) c = compliance change a = crack length University of Bristol

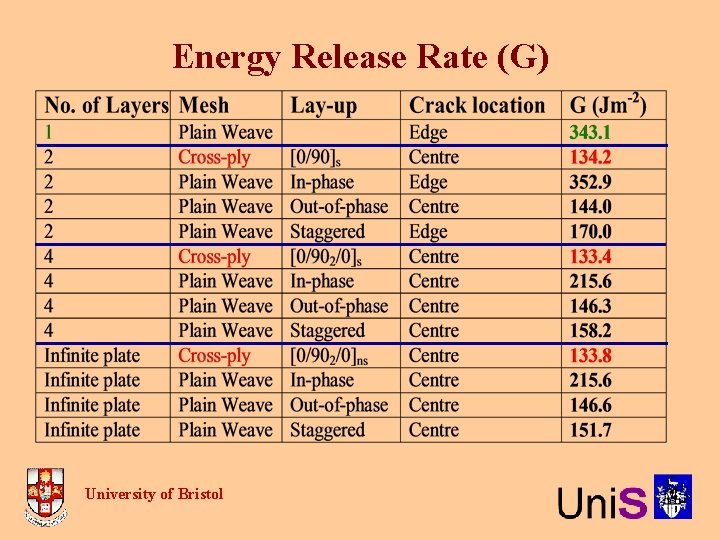

Energy Release Rate (G) University of Bristol

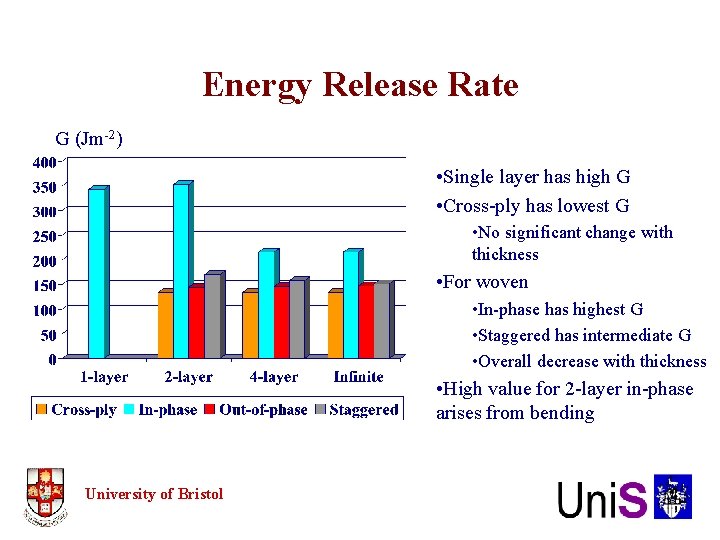

Energy Release Rate G (Jm-2) • Single layer has high G • Cross-ply has lowest G • No significant change with thickness • For woven • In-phase has highest G • Staggered has intermediate G • Overall decrease with thickness • High value for 2 -layer in-phase arises from bending University of Bristol

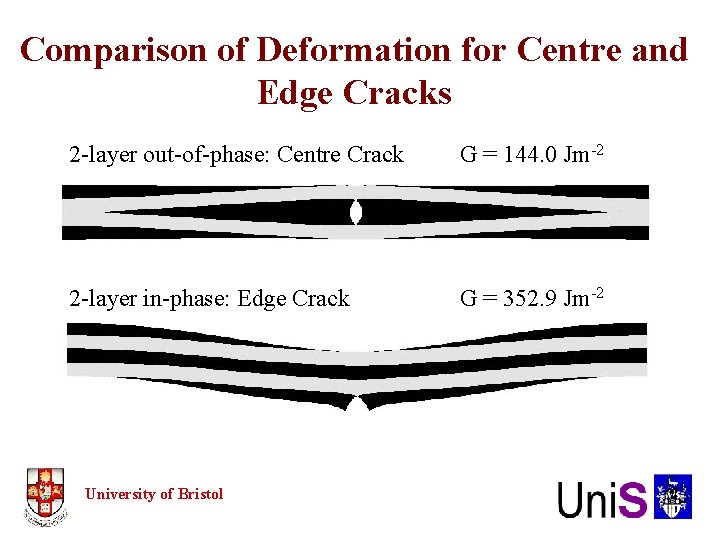

Comparison of Deformation for Centre and Edge Cracks 2 -layer out-of-phase: Centre Crack G = 144. 0 Jm-2 2 -layer in-phase: Edge Crack G = 352. 9 Jm-2 University of Bristol

Conclusions • We have successfully developed finite element models to investigate failure processes in woven fabric composites • Predictions of stiffness show a small but expected dependence on layer shift • Values of fracture energy for transverse crack growth in the 90 o tows can be calculated • Fracture energy is far higher - crack growth is more preferred - when the crack growth causes bending • Fracture energy for cracks that preserve symmetry and in thicker laminates is close to the predicted (and measured) fracture energy for transverse cracking in cross-ply laminates University of Bristol

- Slides: 22