Fil mente 16 17 Lezioni 13 15 Lezioni

- Slides: 29

Fil mente 16 -17 Lezioni 13 -15

• Lezioni 13 -14

Tropism and Anti-Unitarianism • Now, the problem for the tropist approach outlined above is that it must buy Anti-Unitarianism, precisely like Relativistic Reductive Physicalism. This is because mental properties, qua classes of mutually resembling tropes, are partial resemblance classes. • Thus, for example, the mental class of believing that 2+2=4 tropes comprises tropes that resemble each other only partially, since it is a class with physical subclasses, e. g. , P 1 and P 2: all the tropes in P 1 perfectly resemble each other, and the same can be said of all the tropes in P 2, but a trope in P 1 and a trope in P 2 have a lower degree of resemblance.

Relativistic Reductive Physicalism and the tropist approach • In sum, Relativistic Reductive Physicalism and the tropist approach are in a perfectly specular situation: • for the former there are different properties such as P 1 and P 2; • for the latter, the tropes in P 1 do not perfectly resemble the tropes in P 2. • It may be thought that the tropist has an advantage here because, thanks to partial resemblance, the tropes in P 1 and those in P 2 are grouped together in a partial resemblance class. • Yet, analogously, the Relativistic Reductive Physicalist can claim that P 1 and P 2, although different, are somehow similar. After all, the supporter of universals typically claims that there are similarities among universals (see Armstrong (1978)). For example, red, qua color, resembles another color, say green, but not a shape, say rectangularity.

Generic Events as Causal Relata • Given the Kimian conception of events, it seems appropriate to distinguish at least two effects that follow a volition. • When, for example, John wills to raise his arm at t 1, an ensuing effect is no doubt an extremely specific event consisting of John’s exemplifying at time t 2 a very specific arm-raising property, one that involves all sort of details regarding the speed at which the arm moves, the precise inclination of the arm, the distance it reaches from the rest of the body, and so on, and so forth. • Call this very specific property R 321 and, correspondingly, call e 321 the extremely specific event in question.

• Now, given the Kimian conception of event, there isn’t just this event in play, because the property R 321 is, we may say, an ultimate species in a descending chain of less and less specific properties that starts with a most generic arm-raising property, call it R, and continues with more and more specific properties, say R 3, and R 32, up to R 321 (we oversimplify of course, but nothing crucial hinges on this). • In this host of less than fully specific events, there is one that deserves special attention. It is the one that directly corresponds to the content of the volition.

• When John wills to raise his arm, there is an act of willing with a certain content, since it is a volition to raise one’s arm, as opposed to, say, a volition to yell or to raise one’s leg. • This content may be more or less specific, depending on how precisely John intends to control the movement of his arm, but presumably this specificity can never match exactly the specificity of the arm-raising event that actually follows the volition. • It seems in fact that one cannot will to raise one’s arm with precisely that speed and direction, although presumably one wills to raise one’s arm with some kind of speed and direction. • For instance, one may will to do it more or less slowly or with a more or less eastward inclination. The content that deserves special attention is the one whose degree of specificity matches the degree of specificity of the ensuing event.

• John wills: I to raise my arm in way R 32 • e 3 > > e 32 >> e 321 • We say that John wills to raise his arm, but certainly this is typically a necessarily imprecise way of speaking, for in fact John wills to raise his arm in a certain way; not a fully specific one, and yet not a completely generic one. Let us suppose, for example, that the arm-raising property involved in John’s volition is R 32

• In other words, when John wills to raise his arm, he has a volition with a content characterizable by saying that he wills that he himself exemplify the property R 32. • Thus, the event that deserves special attention is the event e 32, the one that most closely matches the content of the volition, since it is an event that consists precisely in the exemplification by John of the very same property, R 32, involved in the content of the volition.

Causal competition: m or p? • Given Supervenience, John’s volition at t 1, call it m, supervenes on a certain physical event, call it p. • If we now ask whether m or p wins the competition for the role of cause of the physical effect which is John’s arm-raising at t 2, we may reply that the answer really depends on whether we focus on the very specific arm-raising event e 321, or the less specific arm-raising event e 32. • We can see this by applying Yablo’s proportionality test to this situation. • Cfr. Yablo, Stephen (1992). "Mental Causation". The Philosophical Review, 101: 245 -280

• According to Yablo, when two candidate events, c 1 and c 2, compete for the role of cause of a certain event e, and one among c 1 and c 2 happens to be more proportional to e than the other one, then it is appropriate to say that the more proportional event, rather than the other event, is the cause of e. • L’evento più proporzionale rispetto all’effetto vince la competizione causale • NB: tipicamente gli eventi in competizione sono in un rapport genere/specie

Esempio: drinking>>guzzling death noise • suppose that Socrates drank the hemlock in a guzzling way, so that he made a certain noise that typically accompanies a guzzling behaviour. • Socrates’s drinking the hemlock wins the competition for the role of causing Socrates’ death, since it appears to be required for the death and enough for it, whereas neither can be said of Socrates’ guzzling the hemlock. • Socrates’ guzzling the hemlock wins the competition for the role of causing the noise, since it appears to be required for the noise and enough for it, whereas neither can be said of Socrates’ simply drinking the hemlock.

• Consider now John’s volition m, and the event p on which it supervenes. • Yablo: p is a determinate of the determinable m • Oppure: p sta ad m come specie a genere • Perché c’è questo rapporto ta m e p? • m può essere realizzato da due eventi neurali leggermente diversi, p e p’ • Analogamente ci può essere rosso con granata o cremisi • Oppure animale con cavallo o gatto

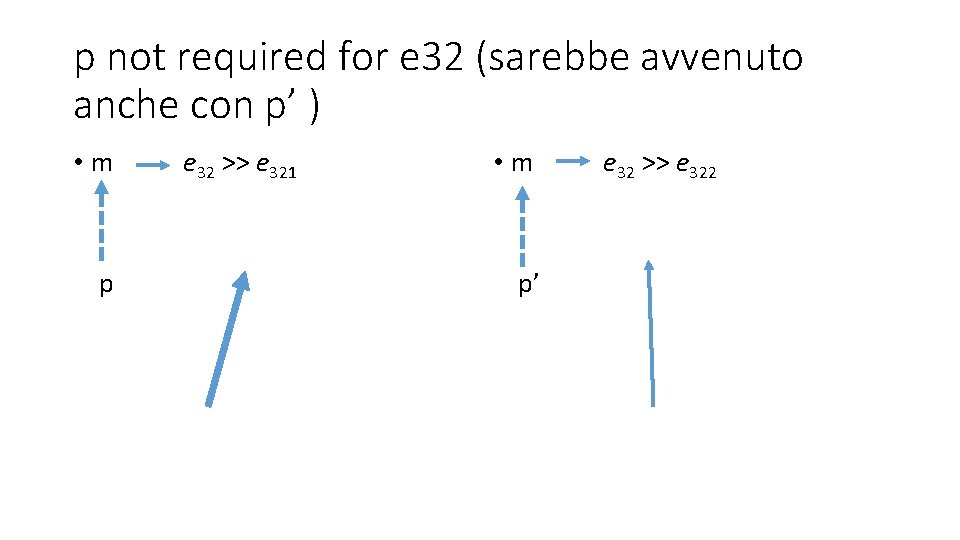

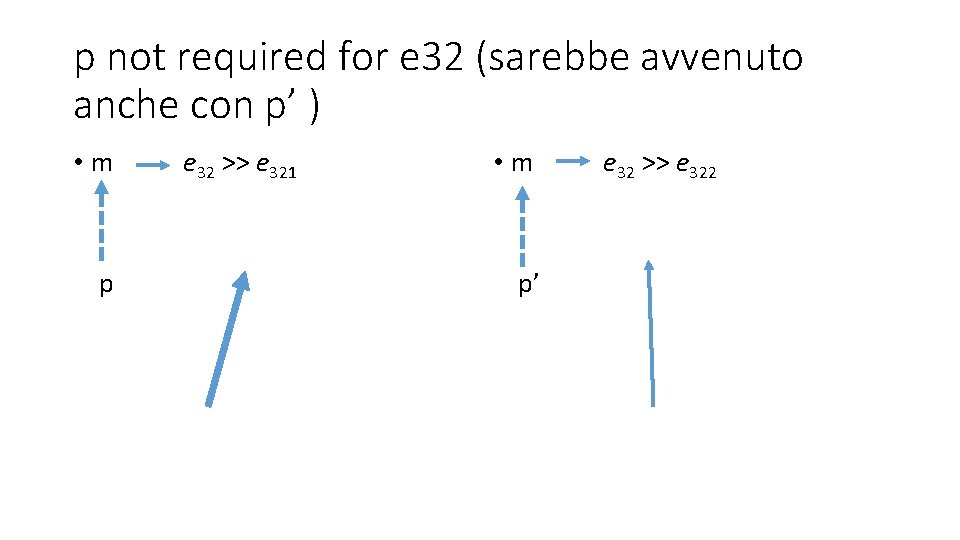

• p genera uno specifico movimento del braccio e 321 • Mondo alternativo: p’ genera uno specifico movimento del braccio e 322 • In entrambi i casi abbiamo il movimento più generico e 32 • In entrambi i i casi c’è la volizione m • Cosa causa e 32 ? • m è più proporzionale di p

p not required for e 32 (sarebbe avvenuto anche con p’ ) • m p e 32 >> e 321 • m p’ e 32 >> e 322

• There is downward causation in this picture, because m is a mental event and e 32 is a physical event, albeit a generic one, as compared to the more specific physical event e 321. • It can be objected that m succeeds in causing e 32, precisely because it supervenes on a physical event p, which in turn causes a completely specific event, e 321 or e 322, that necessitates e 32, by being in a relation of superior specificity to it. • This may well be true, but the fact remains that, given the conception of causation embodied in Yablo’s proportionality test, a differencemaking or dependence conception, one may say, it must be acknowledged that there is downward causation.

• There is a price for this, though, namely the rejection of Causal Closure in the form suggested by Kim, since, as we saw, we are allowing for a physical event, e 32, with a non-physical mental cause, i. e. , m. • However, in virtue of what we have said above, p, qua supervenience base of m, is nomologically sufficient for e 32 (which is different from causing m). • This suggests that we can have this weaker version of Causal Closure: for every physical event, there is a physical event that is nomologically sufficient for it • proposed by Bealer (2007: 25), who says however “causally” rather than “nomologically”

• In the layered model of reality typical of emergentism, there is, according to Kim, a threat of inconsistency because of the tension between upward determination and downward causation. • Nel modello che abbiamo visto: supervenience: upward determination; downward causation: generic mental event as cause • Next model: distinguish between having a causal power and exercising that power (cf. Paolini Paoletti (2016)).

• Lez. 15 • 7/3/16

Possession of a Power Vs. Exercise of the Power • what is upwardly determined are properties understood as causal powers and events consisting in the exemplifications of such powers, which we may call power events. • The events that typically work as causes (if indeed causes are events; a point to which we shall go back below) are those that consist of the exercise of causal powers. these exercise events need not be taken to have a subvenience base that causally compete with them. In particular, when the exercise event is the exercise of a power to will a certain action, a power with which an agent characterizable as free in a libertarian sense is endowed.

• A free agent of this sort is taken to be capable of willing a certain action in such a way that the willing of the action, when it occurs, is not causally determined by preceding events. Such free acts of will are not, let us assume, supervenient on corresponding physical bases. • On the contrary, we can perhaps take them as causally producing the neural events constituting a causal precondition of the ensuing action, insofar as such neural events are not causally determined by preceding physical events – something which can be granted on the assumption, seemingly licensed by current physics, that there is room for indeterminacy in the physical world • see Lowe (2008) for a picture of this sort

• Let us go back to John to illustrate with a concrete example. John has a mental property M’, which is a certain causal power, namely the power of willing to raise one’s arm, or more precisely of willing to raise one’s arm in a certain relatively specific way, e. g. , in such a way as to come to exemplify the property R 32 – which is nevertheless specific than R 321 and R 322, as you will recall. • This mental property M’, like any other of this kind, is upwardly determined, i. e. , it has a subvenient base P’. There is then the event m’ consisting of John’s exemplifying M’ at t 1, by virtue of there being the subvenient event p’ of John’s exemplifying P’ at t. • However, the existence of m’ and p’ is only a precondition of an act of will, or volition, which consists in exercising the causal power which M’ is. • When John wills to raise his arm, he exercises this power, without which he could of course not will to raise his arm. • When John wills to raise his arm at t 1, there is then a certain mental event m consisting of the exemplification at t of a certain property, M, i. e. , willing to raise one’s arm in such a way as to come to exemplify the property R 32. This event m is, we could say, grounded on m’: it could not have occurred without it. And since m’ supervenes on p’, m is also grounded on p’.

• This is certainly downward causation, one that “breaches the causal closure of the physical domain” (Kim (1993: 209)) in a sense deeper than what was entertained in the previous section, because now we can no longer retreat to the weaker version of Causal Closure considered therein • But downward causation and libertarian free will are endorsed without retreating to Cartesian dualism in which the mental level is absolutely independent from the physical level.

• The picture that we have outlined is typically associated to the idea that there is some special form of causation, agent causation. • The idea is to make room for the assumption that all events are caused and yet allow for uncaused causes, i. e. , free agents. • as Lowe (2008) has argued, once we introduce causal powers into the picture, we may well see causation in general as the exercise of causal powers by substances, i. e. , entities endowed with causal powers; in other words, all causation is substance causation

• But if causes are substances rather than events, how are we to understand the model outlined above, in which we assigned to certain kinds of events, volitions, the role of causal relata? • The answer lies in the fact that, as Lowe recognizes, we cannot simply say that a substance, tout court, causes an event. More precisely we must say that a substance, by exercising a certain power, causes a certain event. • This allows one to reduce, as Lowe puts it, event causation to substance causation: To say that an event e is caused by an event c, consisting of the exemplification of property P by substance s at time t, is to say that s, by doing P at t, causes e. • At bottom, one may argue, this amounts to claim that causation is not a dyadic relation between two events, but a four-adic relation involving a substance, a property, a time (s, P and t, in our example) and an event (e, in our example).

On agent causation

Agent causation • The typical agent causationist (Taylor, O' Connor) accepts both agents and events as causal relata. • ball's x hitting ball y caused y's moving • John caused his arm to move • The basic motivation is making room for libertarian free will Emergence and causation - Macerata, 23 -24 Settembre 2015 27

Libertarian free will as motivation • If the cause of my arm movement (or the neuronal arrangement responsible for it) is a (volitional) event, then we have the traditonal libertarian dilemma (see Lowe PERSONAL AGENCY, p. 129) • either the volitional event is caused (by previous events) and thus not free or it is uncaused and thus appears to be random and then again not free • The response is to say that the cause is not an event (something for which it is legitimate to ask whether or not it was caused), but an agent (causing the event for a reason (a belief, a desire)) Emergence and causation - Macerata, 23 -24 Settembre 2015 28

Lowe on agent and substance causation • In ch. 7 of PA Lowe defends the view that agent causation is a special case of substance causation (p. 141) and that event causation is reducible to substance causation. • In other words, causal relata are substances; (rational) agents are special cases of substances • There is still the motivation of saving libertarian free will Emergence and causation - Macerata, 23 -24 Settembre 2015 29