Figure 2 17 Relationship of layers and addresses

- Slides: 33

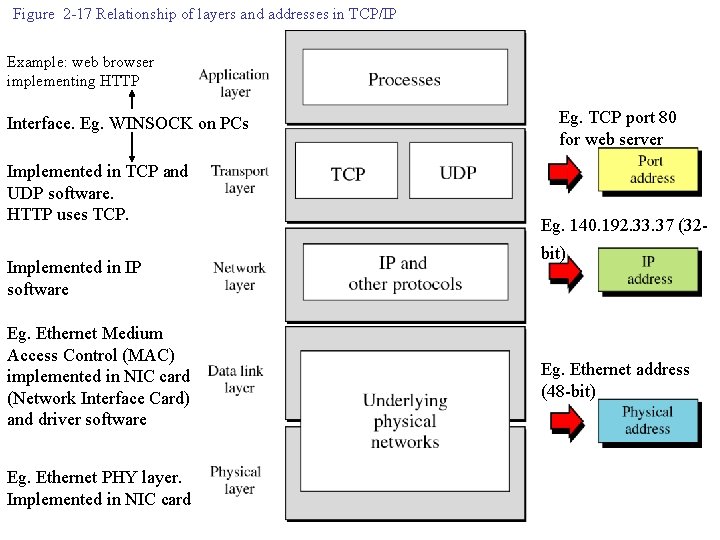

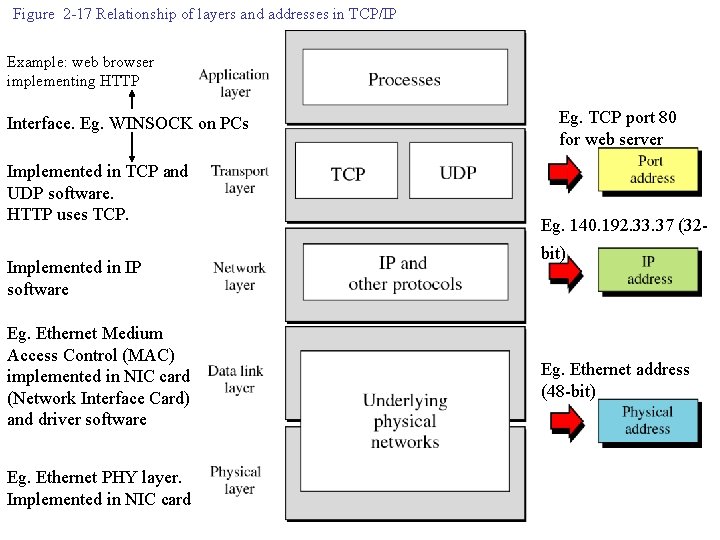

Figure 2 -17 Relationship of layers and addresses in TCP/IP Example: web browser implementing HTTP Interface. Eg. WINSOCK on PCs Implemented in TCP and UDP software. HTTP uses TCP. Implemented in IP software Eg. Ethernet Medium Access Control (MAC) implemented in NIC card (Network Interface Card) and driver software Eg. Ethernet PHY layer. Implemented in NIC card Eg. TCP port 80 for web server Eg. 140. 192. 33. 37 (32 - bit) Eg. Ethernet address (48 -bit)

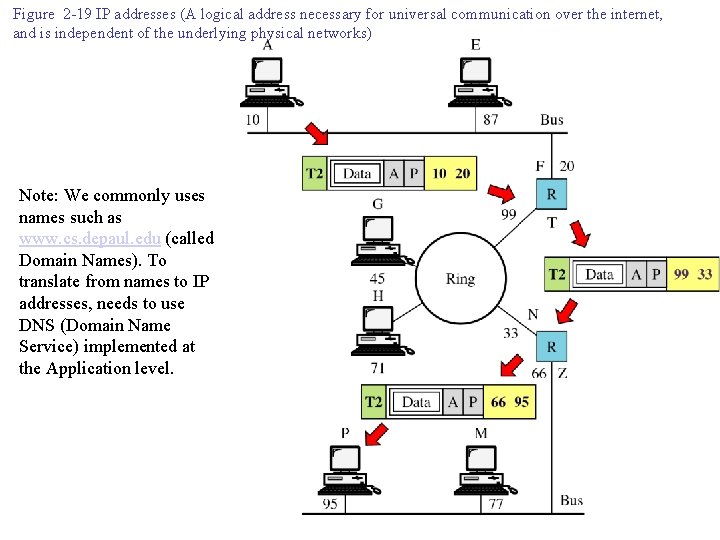

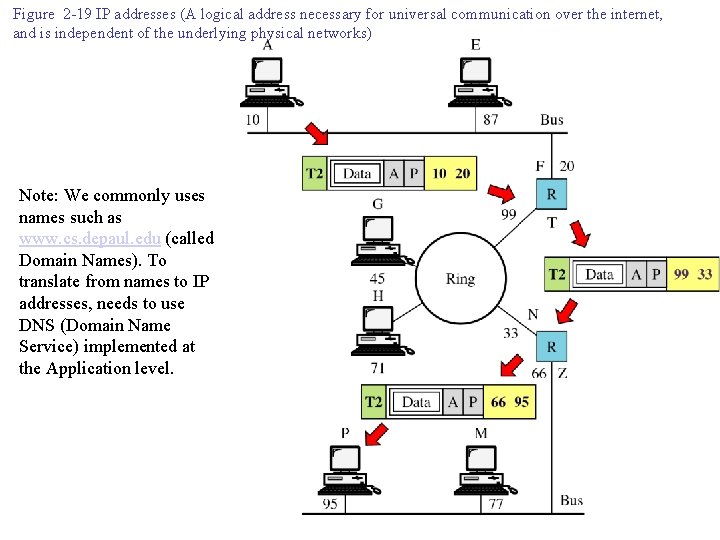

Figure 2 -19 IP addresses (A logical address necessary for universal communication over the internet, and is independent of the underlying physical networks) Note: We commonly uses names such as www. cs. depaul. edu (called Domain Names). To translate from names to IP addresses, needs to use DNS (Domain Name Service) implemented at the Application level.

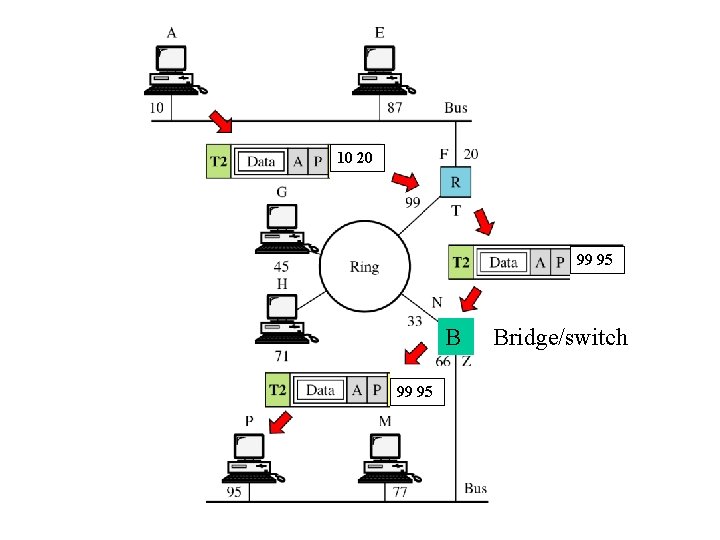

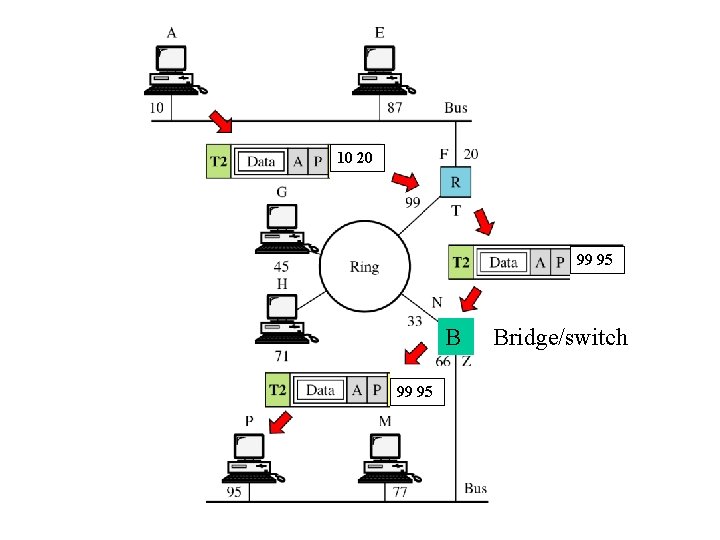

10 20 99 95 Bridge/switch

IP Addressing

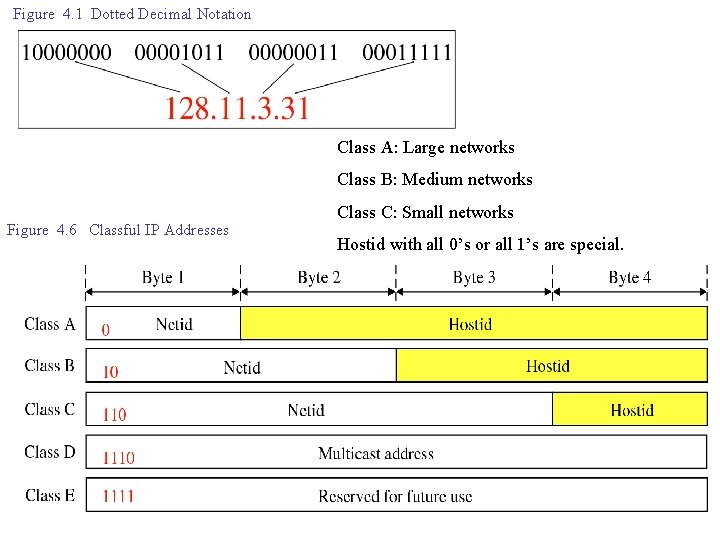

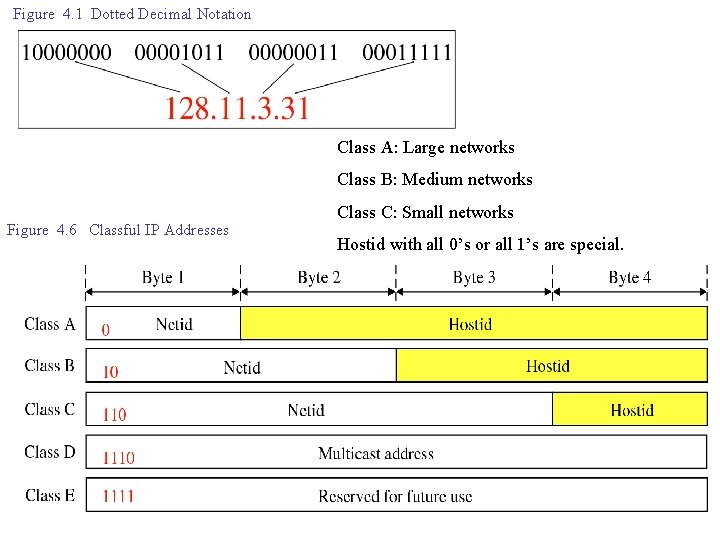

Figure 4. 1 Dotted Decimal Notation Class A: Large networks Class B: Medium networks Figure 4. 6 Classful IP Addresses Class C: Small networks Hostid with all 0’s or all 1’s are special.

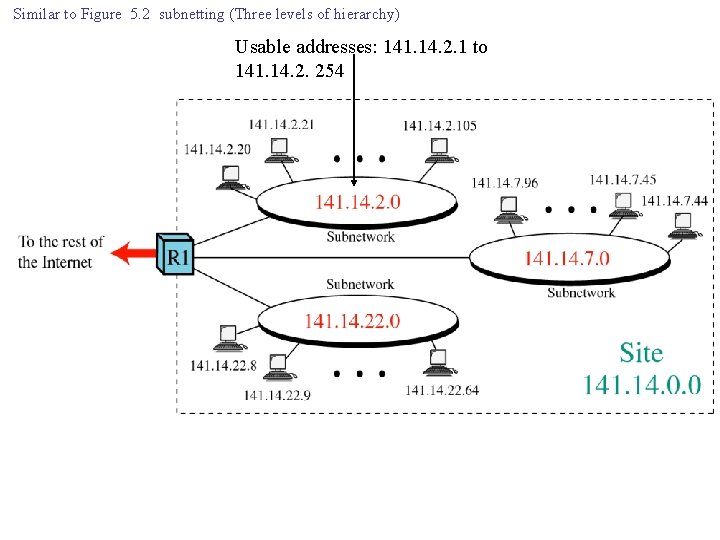

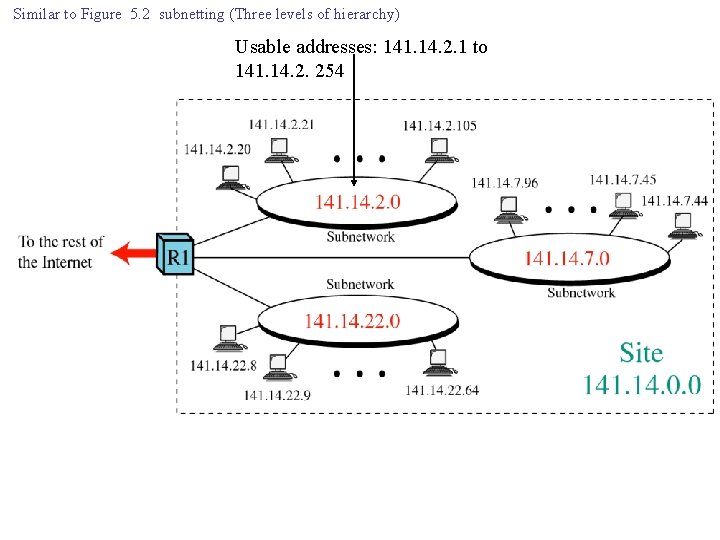

Similar to Figure 5. 2 subnetting (Three levels of hierarchy) Usable addresses: 141. 14. 2. 1 to 141. 14. 2. 254

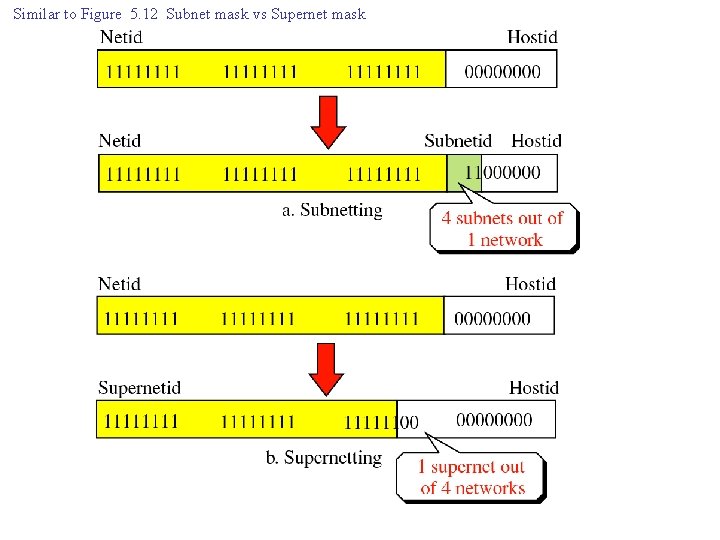

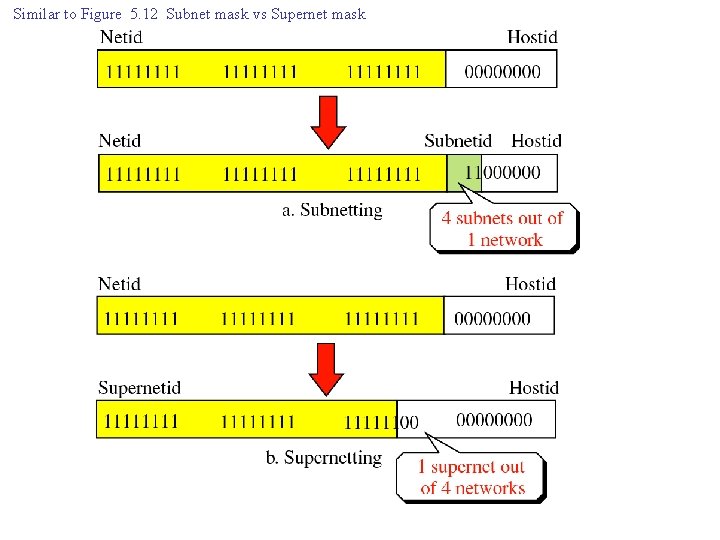

Similar to Figure 5. 12 Subnet mask vs Supernet mask

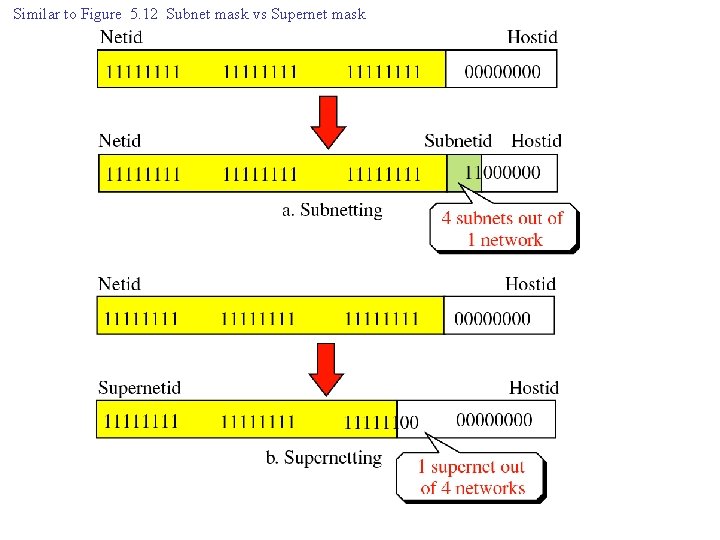

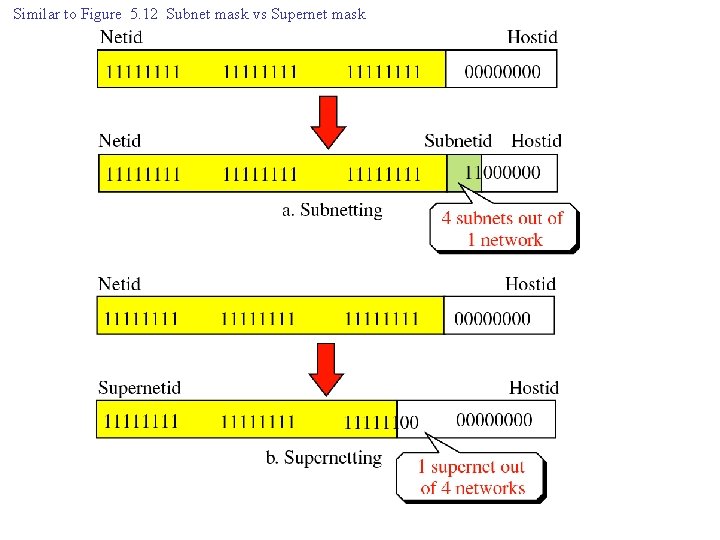

Similar to Figure 5. 12 Subnet mask vs Supernet mask

Classless Interdomain Routing (CIDR)

ARP RARP IP ICMP BOOTP DHCP

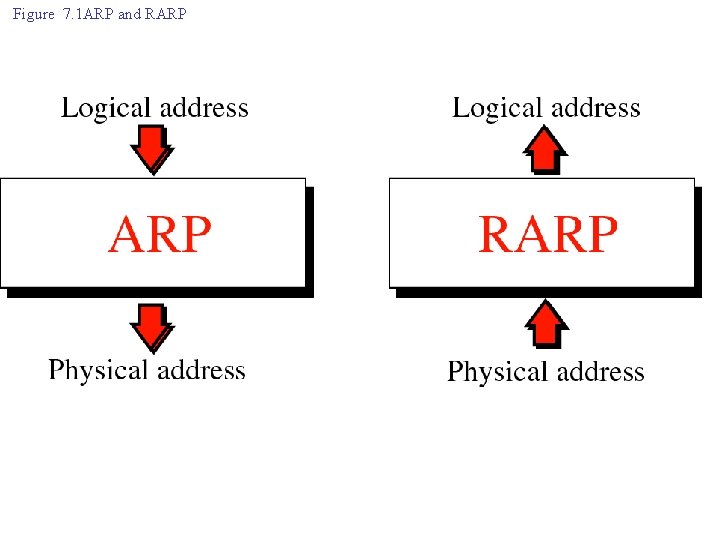

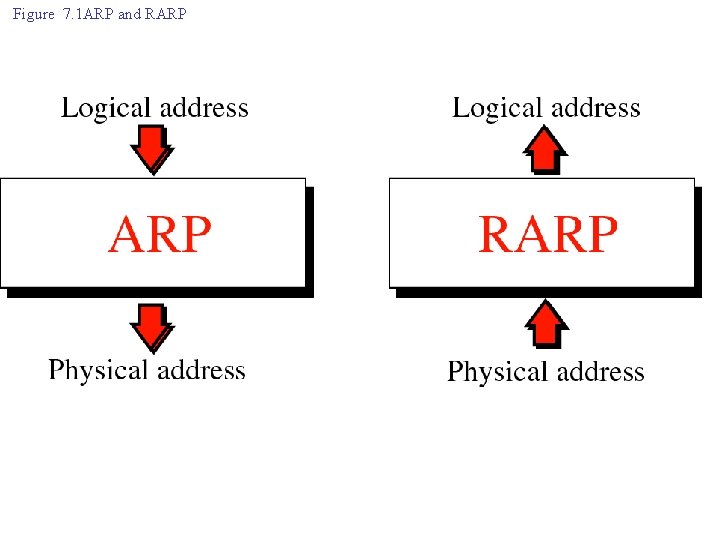

Figure 7. 1 ARP and RARP

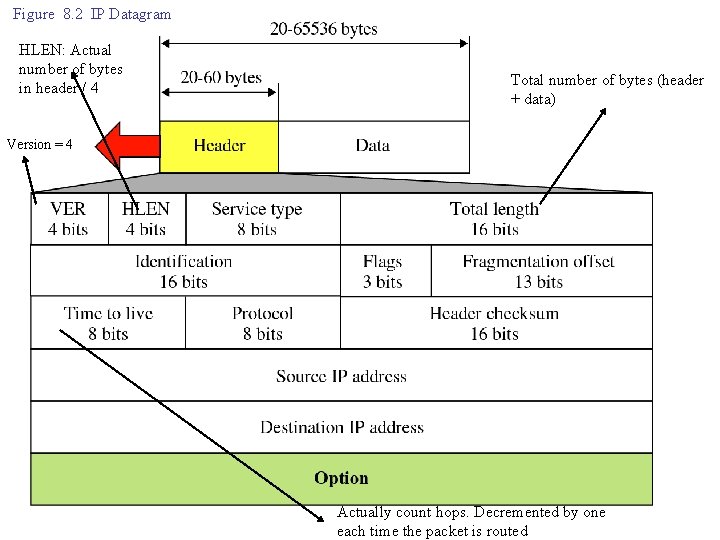

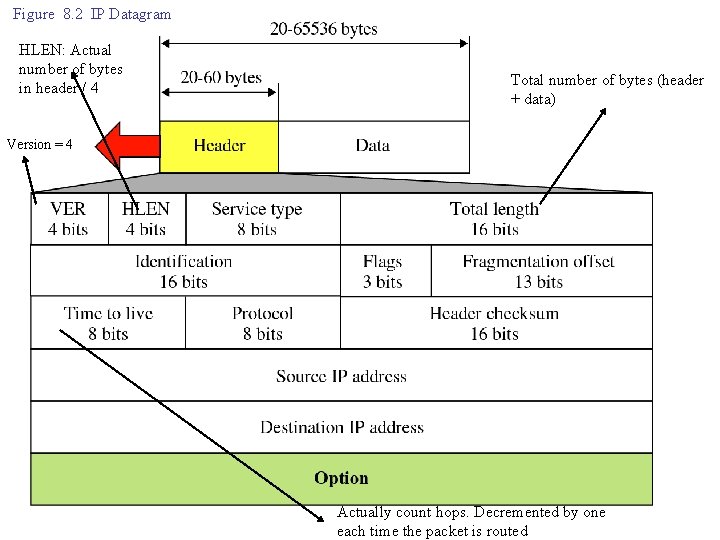

Figure 8. 2 IP Datagram HLEN: Actual number of bytes in header / 4 Total number of bytes (header + data) Version = 4 Actually count hops. Decremented by one each time the packet is routed

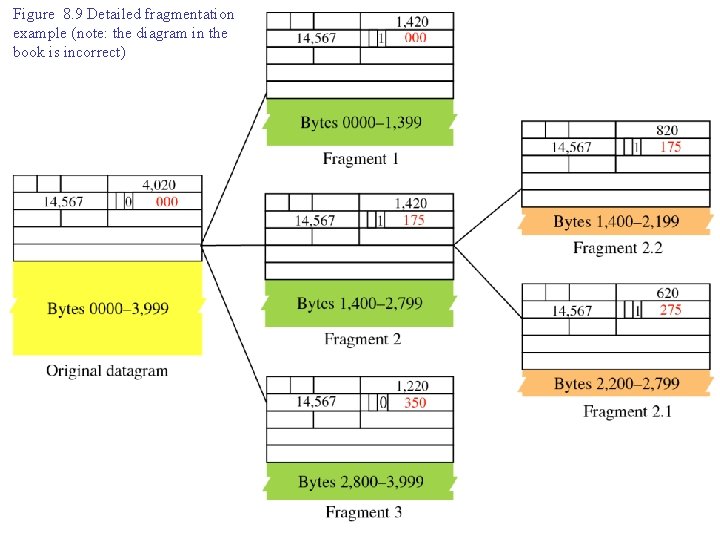

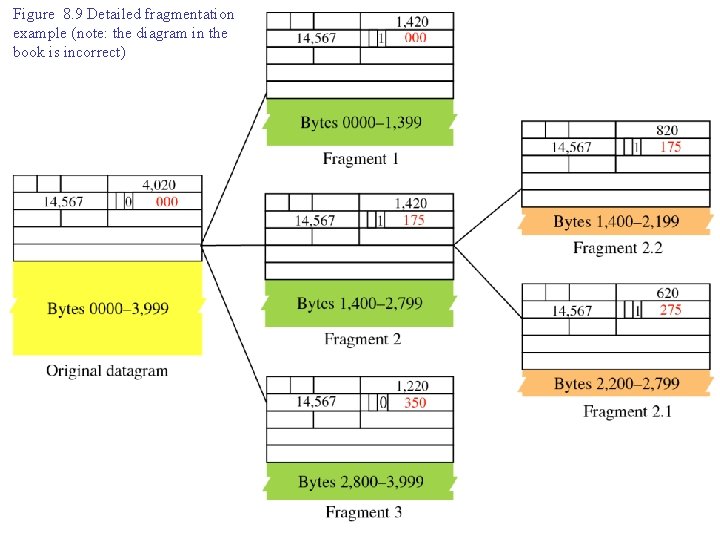

Figure 8. 9 Detailed fragmentation example (note: the diagram in the book is incorrect)

Transport Layer - UDP

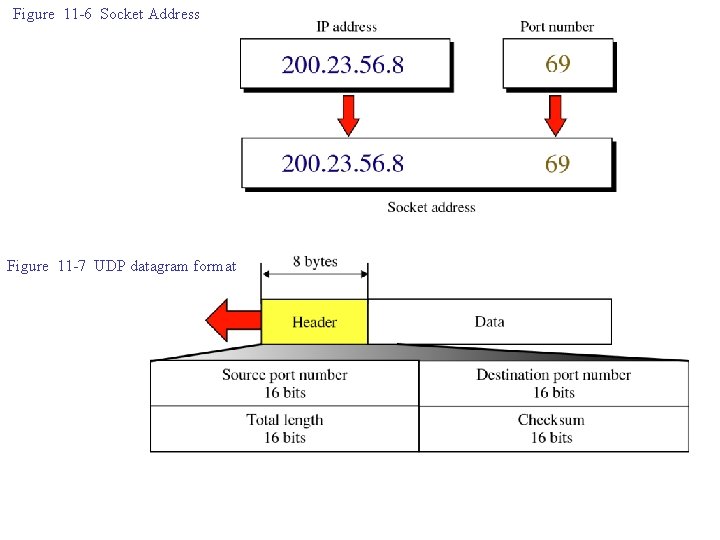

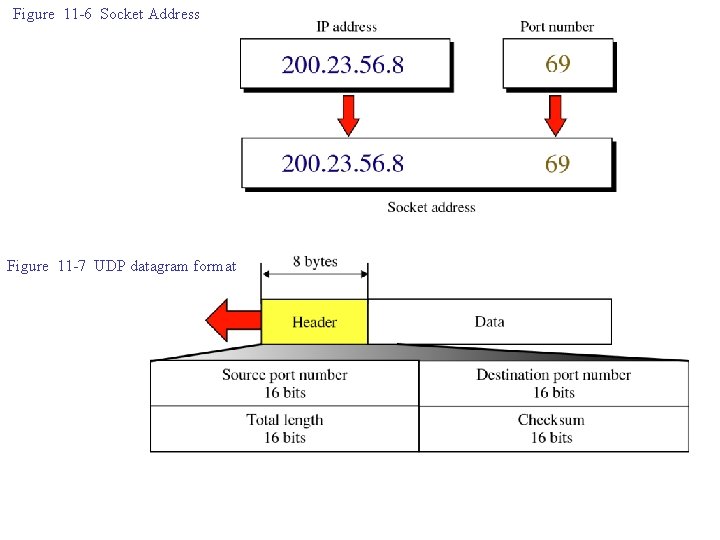

Figure 11 -6 Socket Address Figure 11 -7 UDP datagram format

Transport Layer - TCP

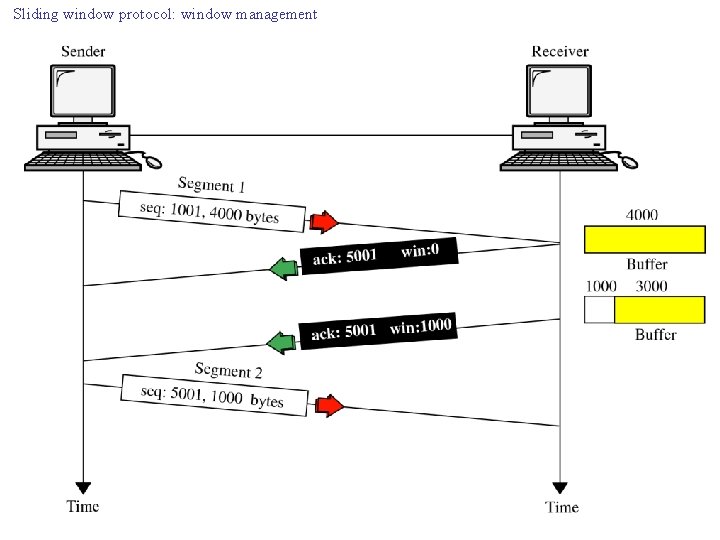

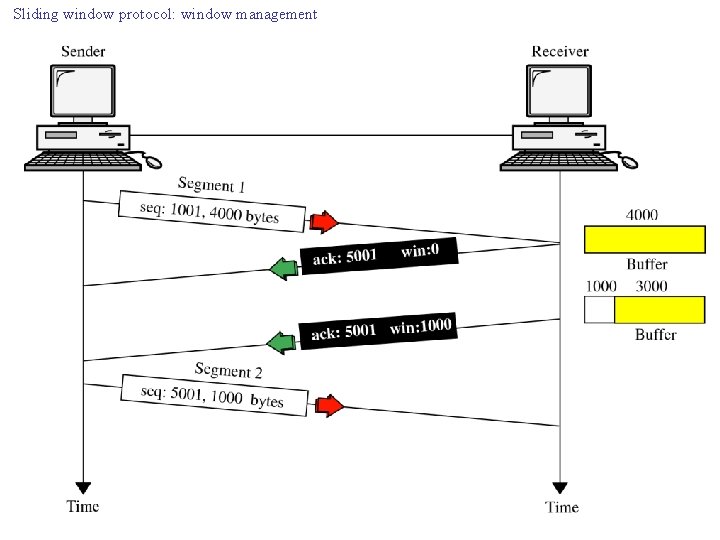

Sliding window protocol: window management

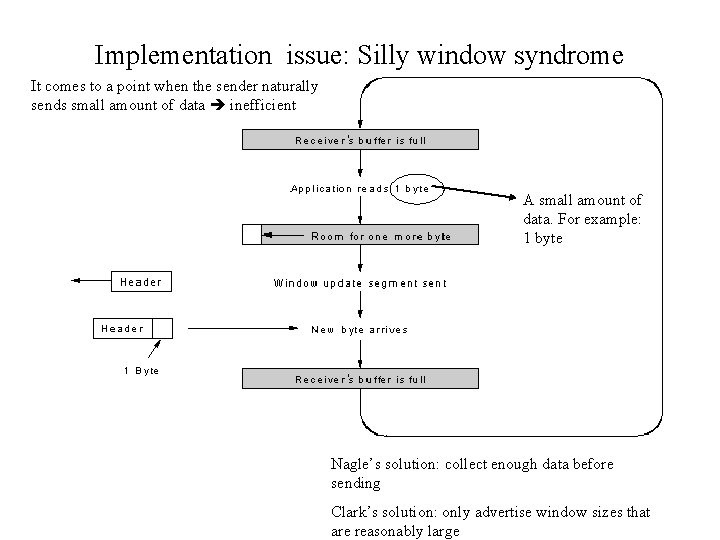

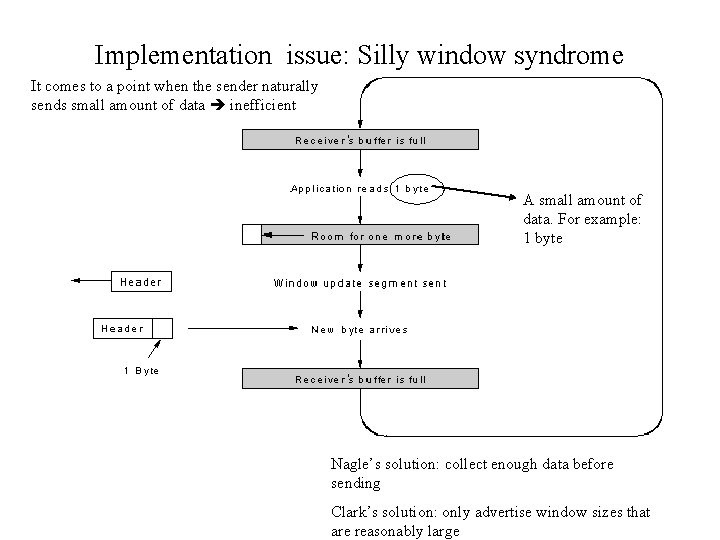

Implementation issue: Silly window syndrome It comes to a point when the sender naturally sends small amount of data inefficient A small amount of data. For example: 1 byte Nagle’s solution: collect enough data before sending Clark’s solution: only advertise window sizes that are reasonably large

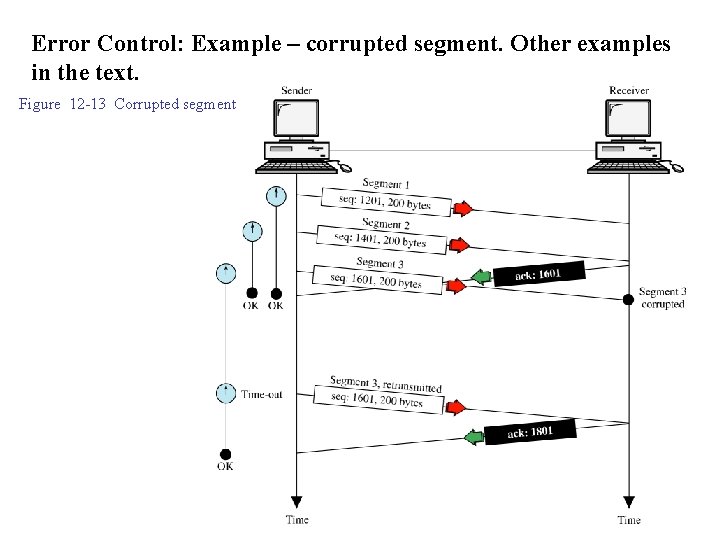

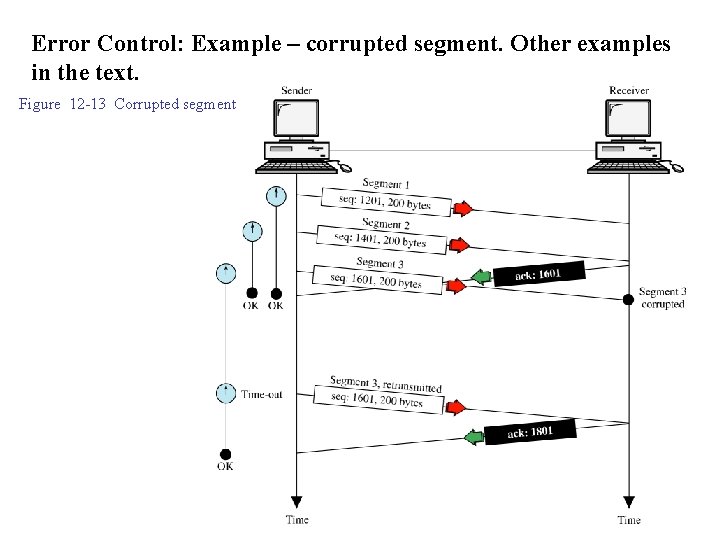

Error Control: Example – corrupted segment. Other examples in the text. Figure 12 -13 Corrupted segment

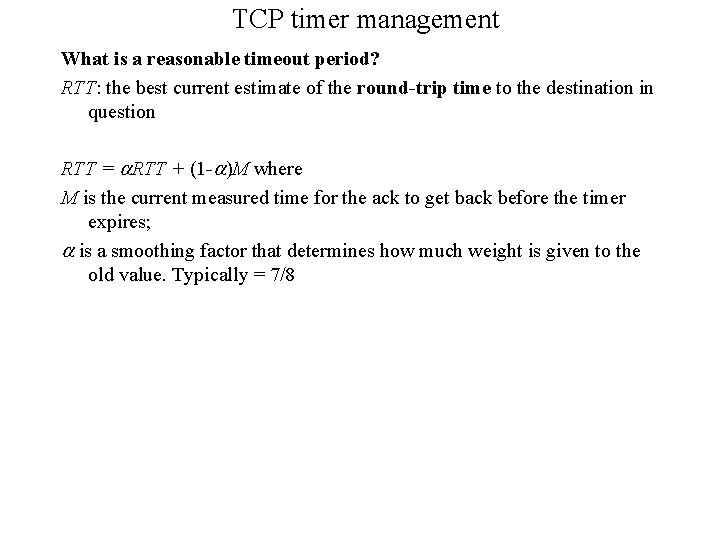

TCP timer management What is a reasonable timeout period? RTT: the best current estimate of the round-trip time to the destination in question RTT = RTT + (1 - )M where M is the current measured time for the ack to get back before the timer expires; is a smoothing factor that determines how much weight is given to the old value. Typically = 7/8

TCP timer management Karn's alogirthm When retransmission occurs, one cannot tell which transmission an Ack corresponds to, and the estimate of RRT will not be accurate. Karn proposed that RTT not updated, but timeout doubled, until you send a segment and receive an acknowledgment without the need for retransmission. (Note: Recall that RTT timeout) Persistence Timer For zero-window probe: Whenever a window closes completely, the sender periodically probes the receiver with small amount to data (because a lost window update may cause a deadlock. ) Keepalive Timer When a connection has been idle for a long time, check to see if the other side is still there. Time-Waited Timer During connection termination. A connection is not considered really closed until the end of a time-waited period. Usually two times the expected lifetime of a segment

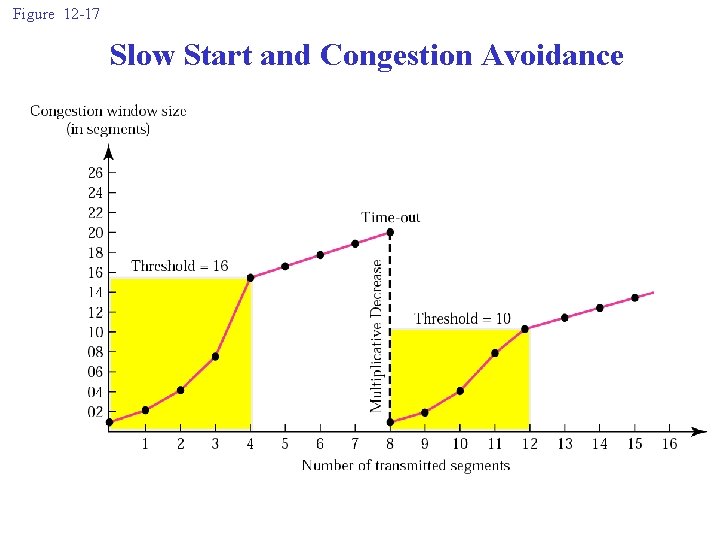

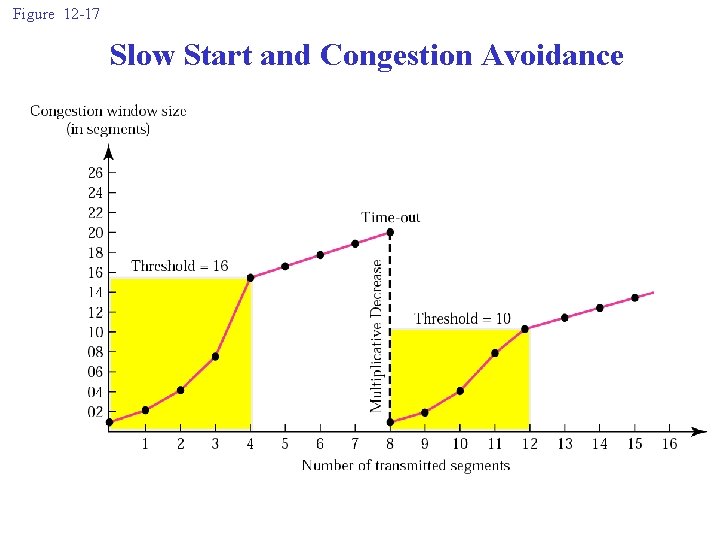

Figure 12 -17 Slow Start and Congestion Avoidance

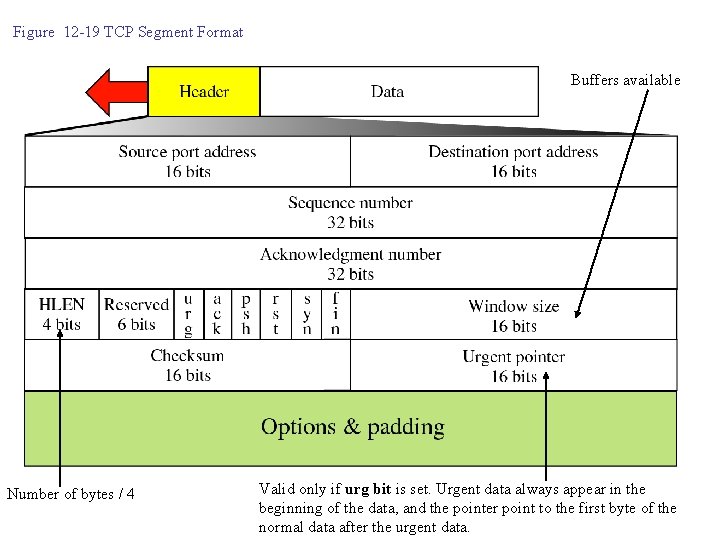

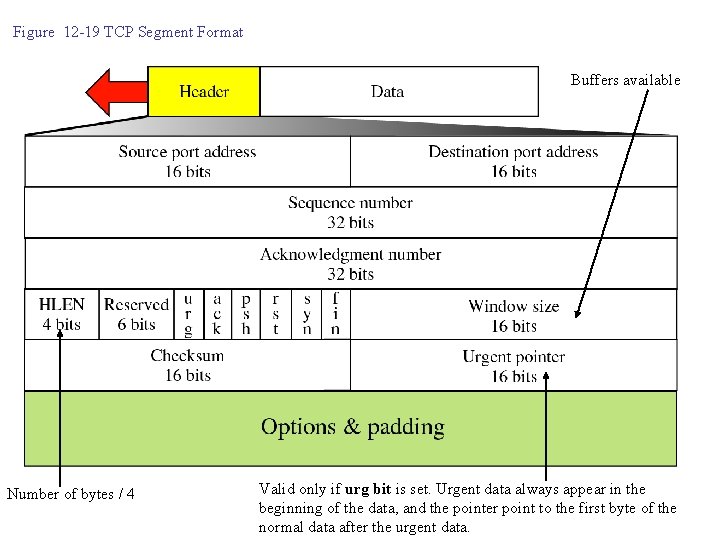

Figure 12 -19 TCP Segment Format Buffers available Number of bytes / 4 Valid only if urg bit is set. Urgent data always appear in the beginning of the data, and the pointer point to the first byte of the normal data after the urgent data.

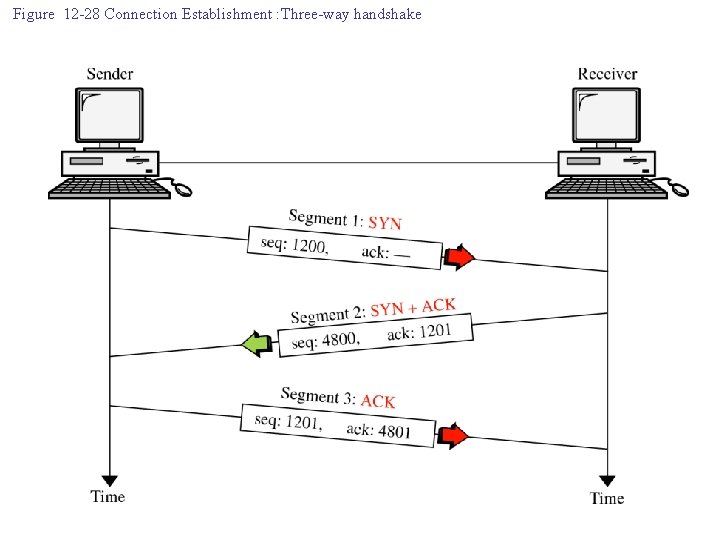

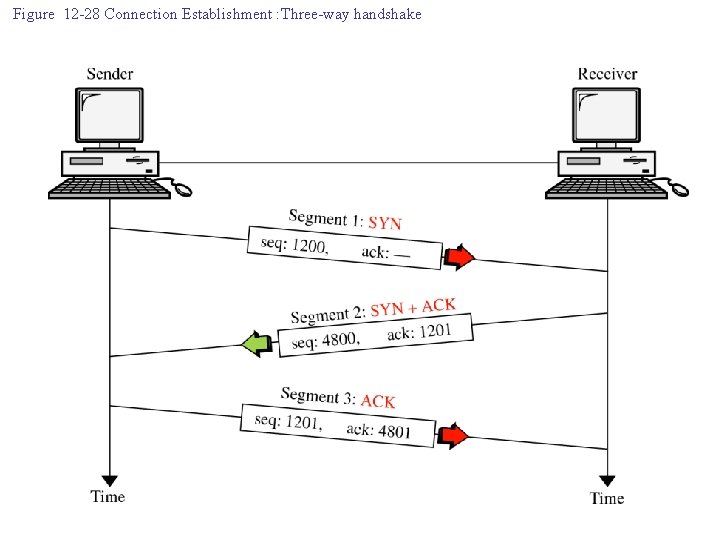

Figure 12 -28 Connection Establishment : Three-way handshake

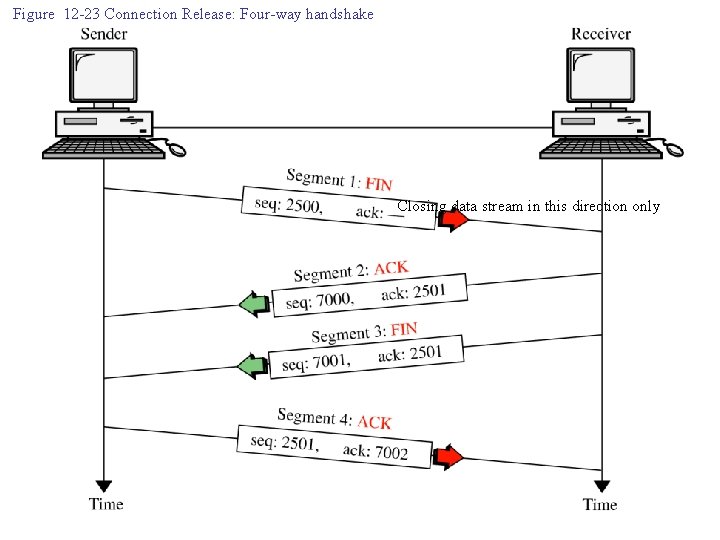

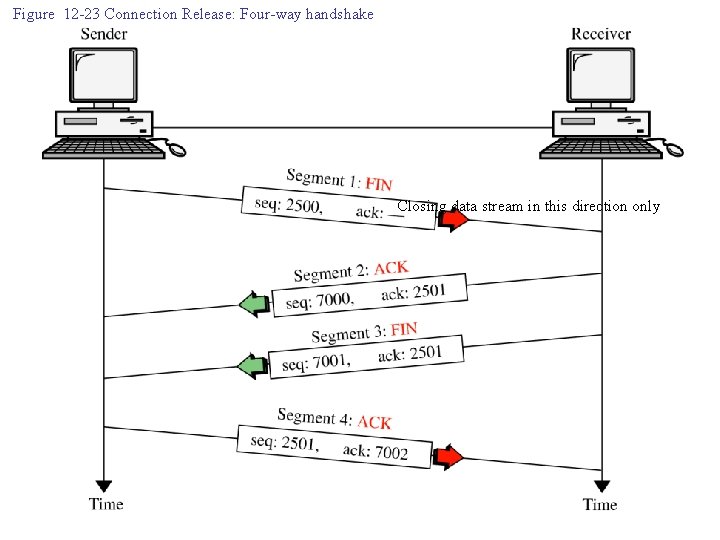

Figure 12 -23 Connection Release: Four-way handshake Closing data stream in this direction only

Routing

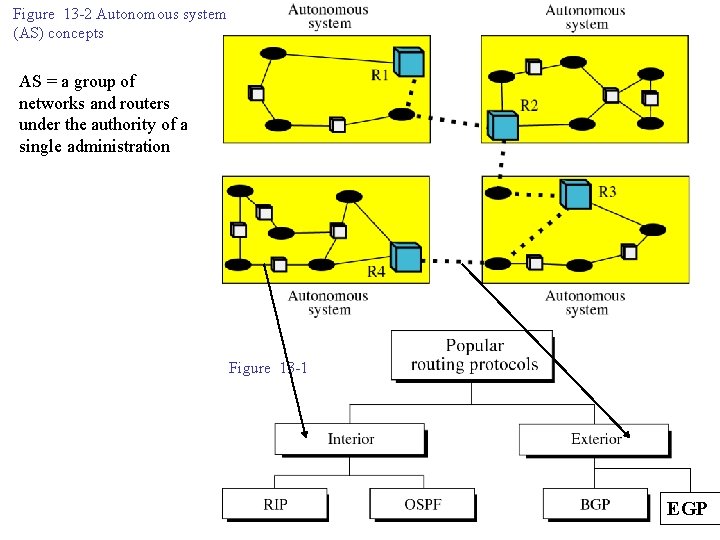

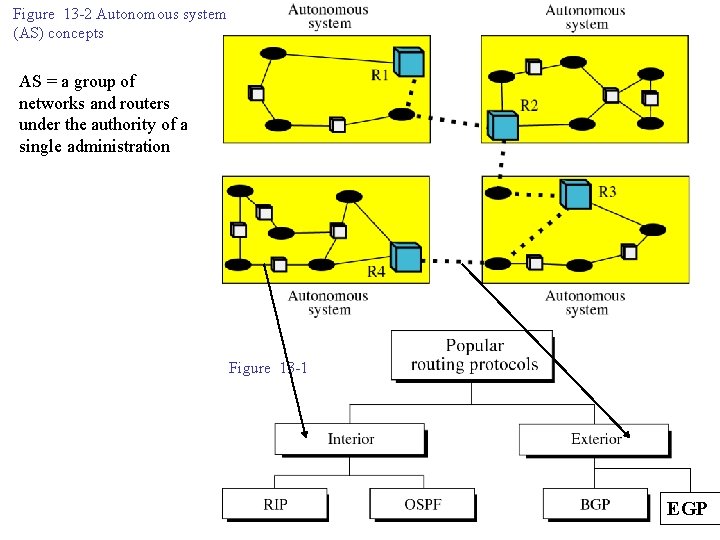

Figure 13 -2 Autonomous system (AS) concepts AS = a group of networks and routers under the authority of a single administration Figure 13 -1 EGP

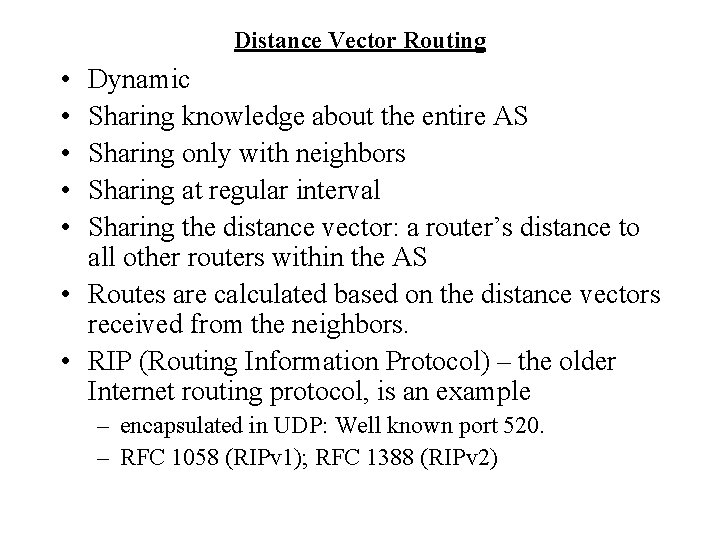

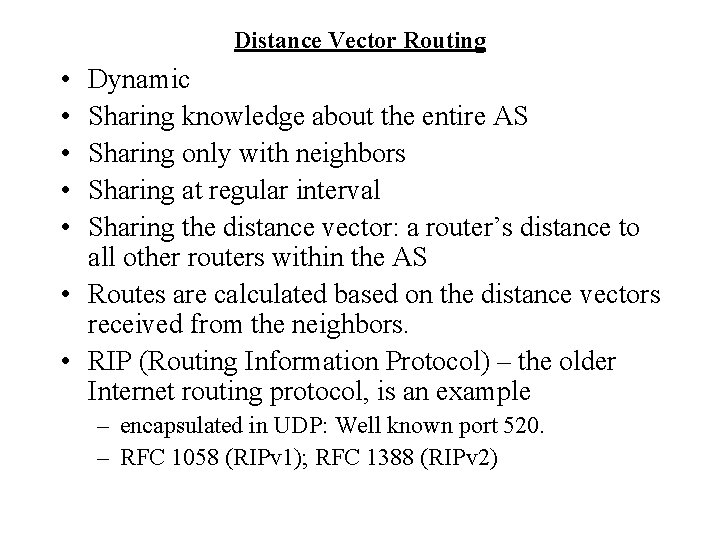

Distance Vector Routing • • • Dynamic Sharing knowledge about the entire AS Sharing only with neighbors Sharing at regular interval Sharing the distance vector: a router’s distance to all other routers within the AS • Routes are calculated based on the distance vectors received from the neighbors. • RIP (Routing Information Protocol) – the older Internet routing protocol, is an example – encapsulated in UDP: Well known port 520. ( – RFC 1058 (RIPv 1); RFC 1388 (RIPv 2)

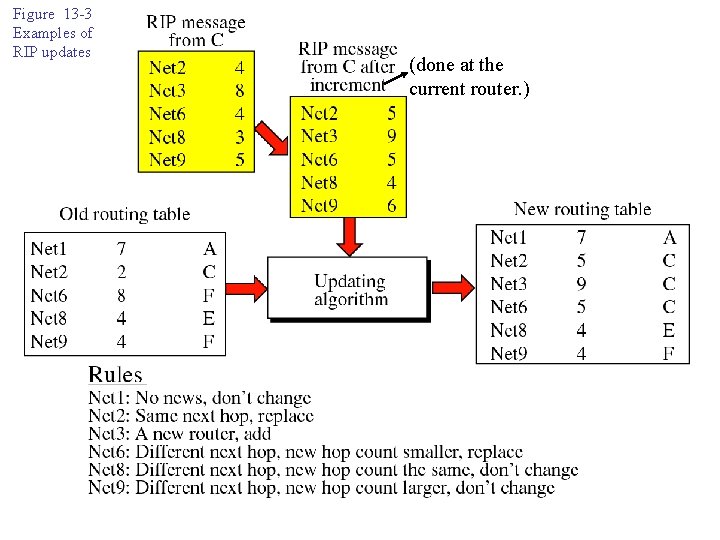

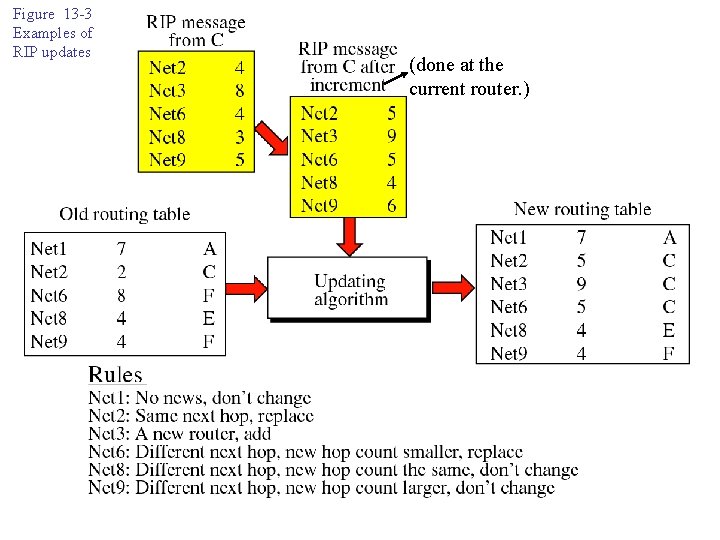

Figure 13 -3 Examples of RIP updates (done at the current router. )

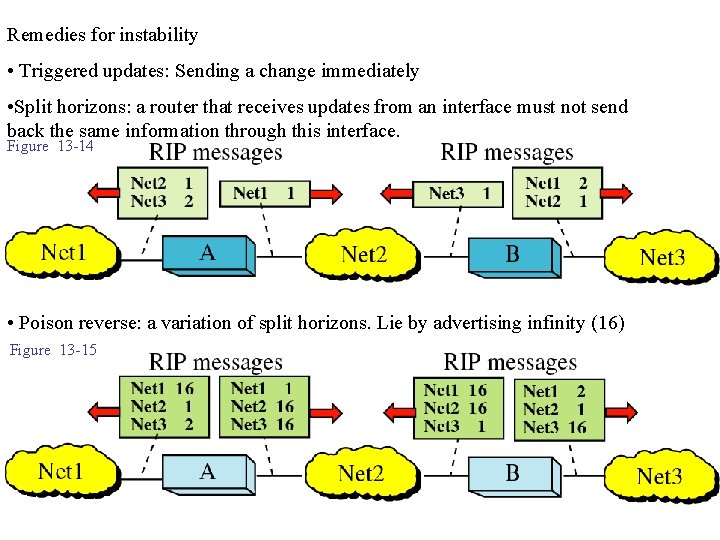

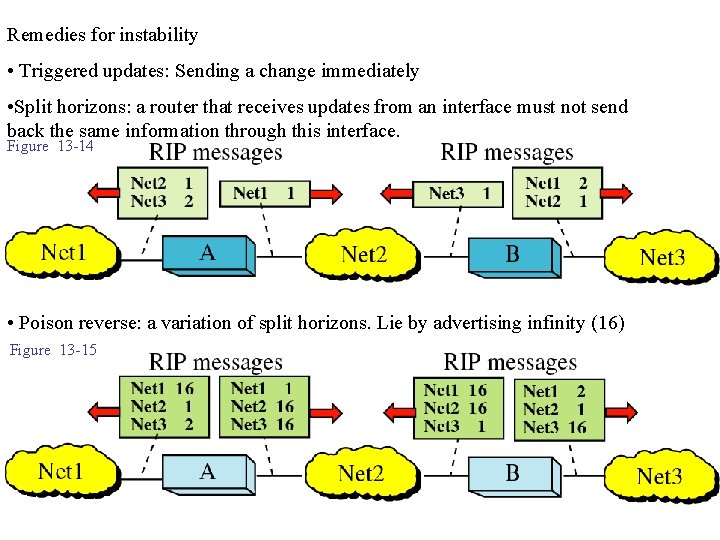

Remedies for instability • Triggered updates: Sending a change immediately • Split horizons: a router that receives updates from an interface must not send back the same information through this interface. Figure 13 -14 • Poison reverse: a variation of split horizons. Lie by advertising infinity (16) Figure 13 -15

Link State Routing • Dynamic • Sharing knowledge about the neighborhood- link states: who I am directly connected to and the distance (based on minimum delay, maximum throughput, cost, hop counts etc. ) • Sharing with every other router – broadcast by flooding • Sharing when there is a change • OSPF (Open Shortest Path First), the newer Internet routing protocol is an example. • General steps – – – Hello: discovering reachability Build link state packets (advertisements) Broadcast the link state packets: initially and when there are changes Build a map from the received link state packets From the map calculate the shortest path

Dijkstra Algorithm: for calculating shortest paths 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. Start with the local node (router): the root of the tree Assign a cost of 0 to this node and make it the first permanent node. Examine each non-permanent neighbor node of the node that was the last permanent node. Assign a cumulative cost to each node and make it tentative Among the list of tentative nodes 1. 2. Find the node with the smallest cumulative cost and make it permanent If a node can be reached from more than one direction 1. 6. Select the direction with the shortest cumulative cost. Repeat steps 3 to 5 until every node becomes permanent

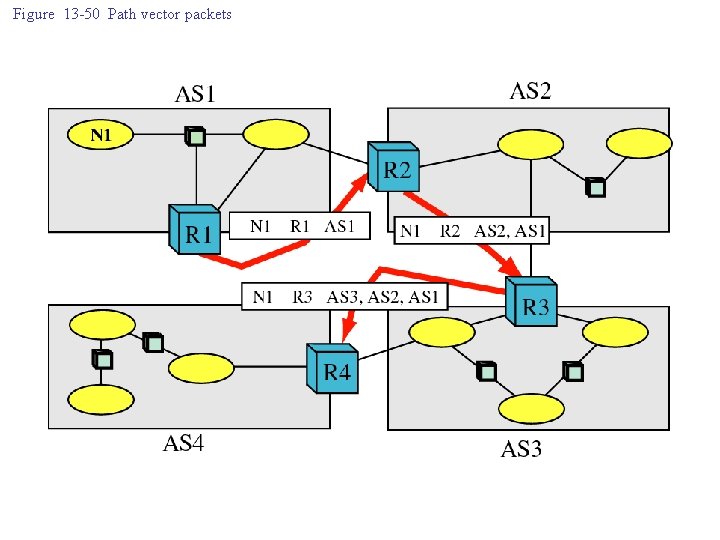

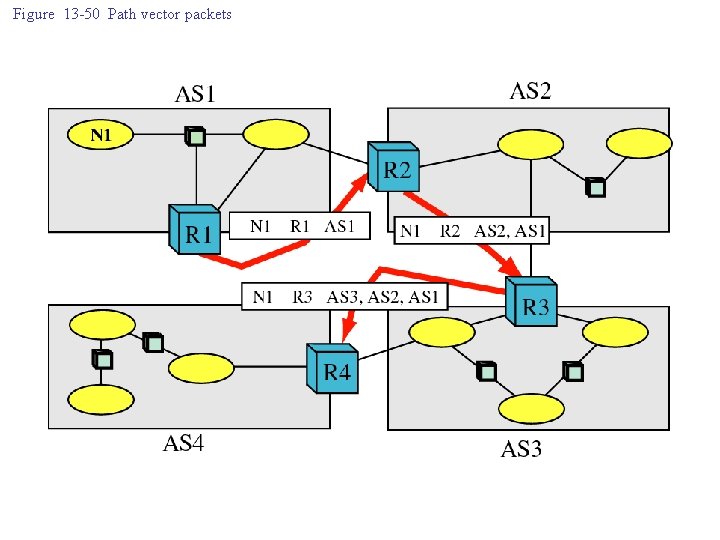

Figure 13 -50 Path vector packets