Fig 1 A wiring diagram for the SCEC

- Slides: 9

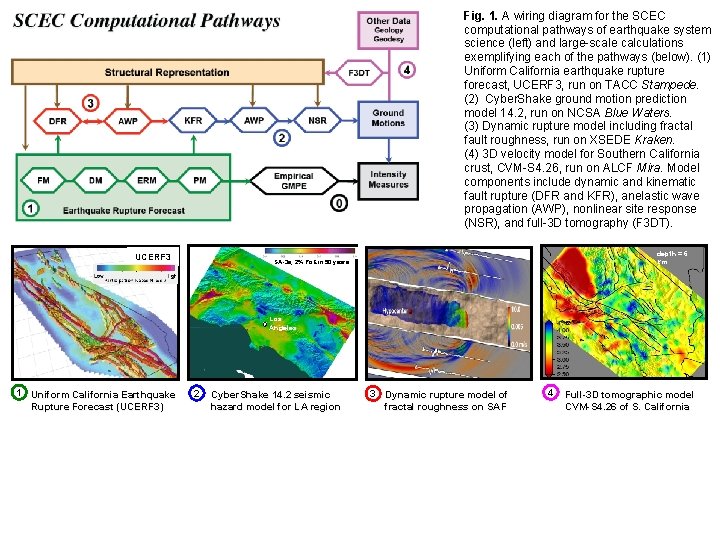

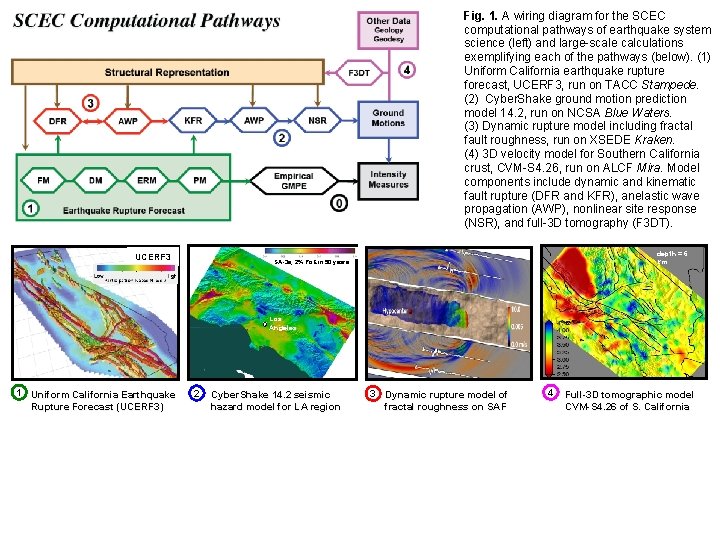

Fig. 1. A wiring diagram for the SCEC computational pathways of earthquake system science (left) and large-scale calculations exemplifying each of the pathways (below). (1) Uniform California earthquake rupture forecast, UCERF 3, run on TACC Stampede. (2) Cyber. Shake ground motion prediction model 14. 2, run on NCSA Blue Waters. (3) Dynamic rupture model including fractal fault roughness, run on XSEDE Kraken. (4) 3 D velocity model for Southern California crust, CVM-S 4. 26, run on ALCF Mira. Model components include dynamic and kinematic fault rupture (DFR and KFR), anelastic wave propagation (AWP), nonlinear site response (NSR), and full-3 D tomography (F 3 DT). UCERF 3 depth = 6 km SA-3 s, 2% Po. E in 50 years Los Angeles 1 Uniform California Earthquake Rupture Forecast (UCERF 3) 2 Cyber. Shake 14. 2 seismic hazard model for LA region 3 Dynamic rupture model of fractal roughness on SAF 4 Full-3 D tomographic model CVM-S 4. 26 of S. California

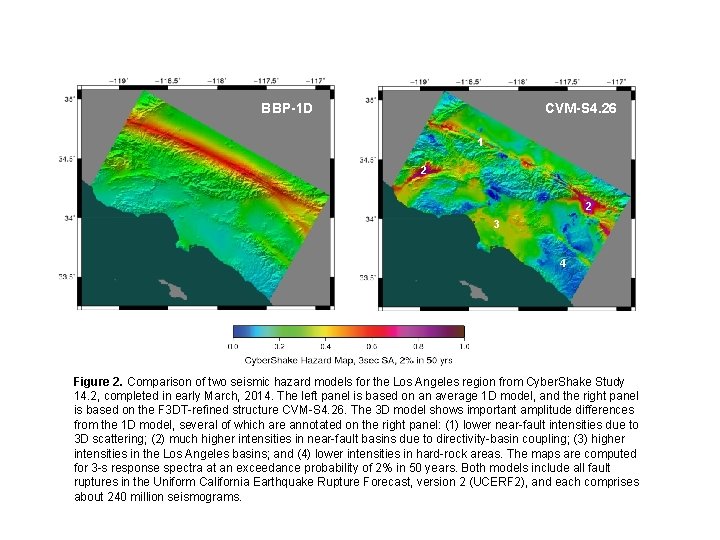

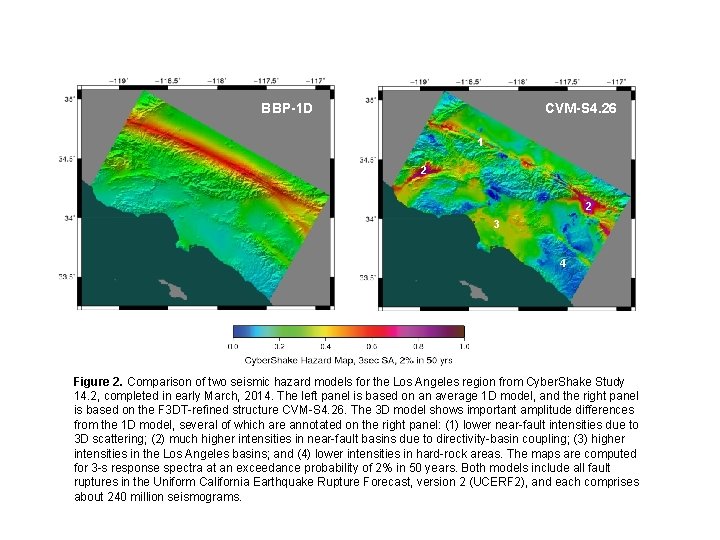

BBP-1 D CVM-S 4. 26 1 2 2 3 4 Figure 2. Comparison of two seismic hazard models for the Los Angeles region from Cyber. Shake Study 14. 2, completed in early March, 2014. The left panel is based on an average 1 D model, and the right panel is based on the F 3 DT-refined structure CVM-S 4. 26. The 3 D model shows important amplitude differences from the 1 D model, several of which are annotated on the right panel: (1) lower near-fault intensities due to 3 D scattering; (2) much higher intensities in near-fault basins due to directivity-basin coupling; (3) higher intensities in the Los Angeles basins; and (4) lower intensities in hard-rock areas. The maps are computed for 3 -s response spectra at an exceedance probability of 2% in 50 years. Both models include all fault ruptures in the Uniform California Earthquake Rupture Forecast, version 2 (UCERF 2), and each comprises about 240 million seismograms.

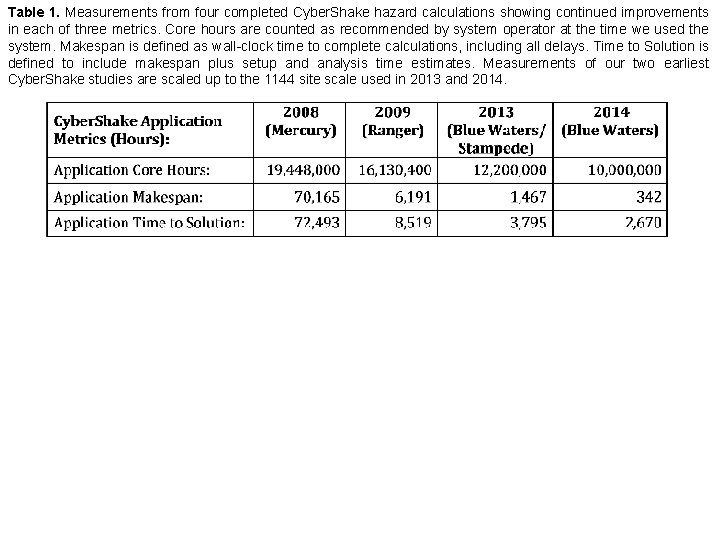

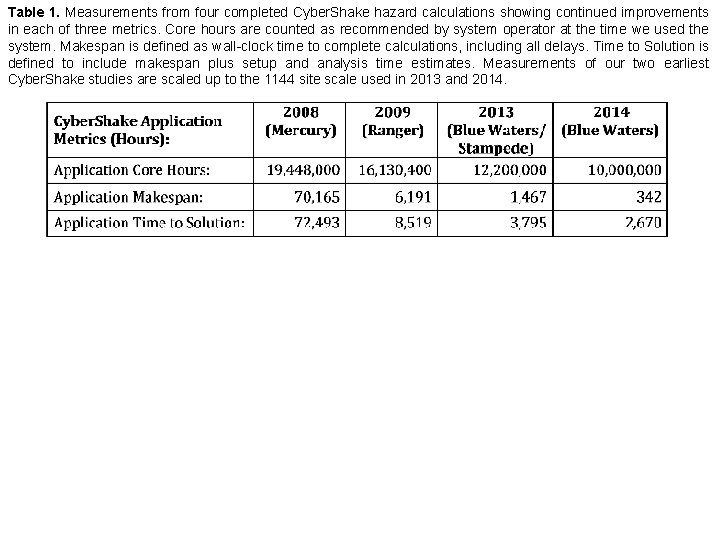

Table 1. Measurements from four completed Cyber. Shake hazard calculations showing continued improvements in each of three metrics. Core hours are counted as recommended by system operator at the time we used the system. Makespan is defined as wall-clock time to complete calculations, including all delays. Time to Solution is defined to include makespan plus setup and analysis time estimates. Measurements of our two earliest Cyber. Shake studies are scaled up to the 1144 site scale used in 2013 and 2014.

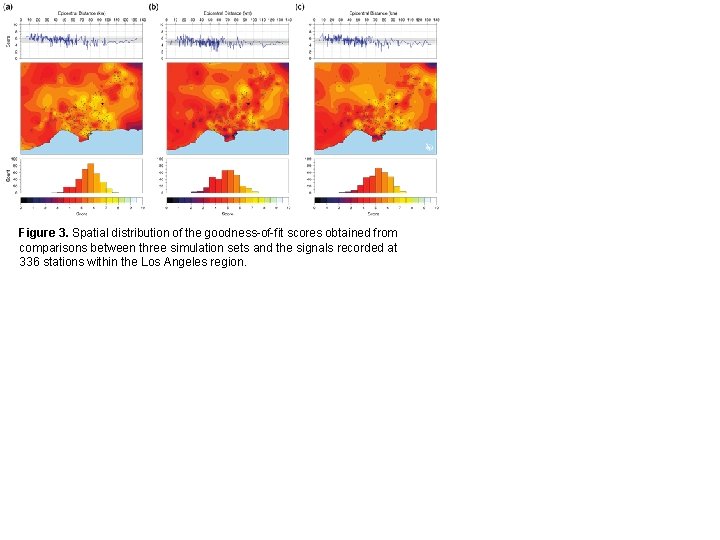

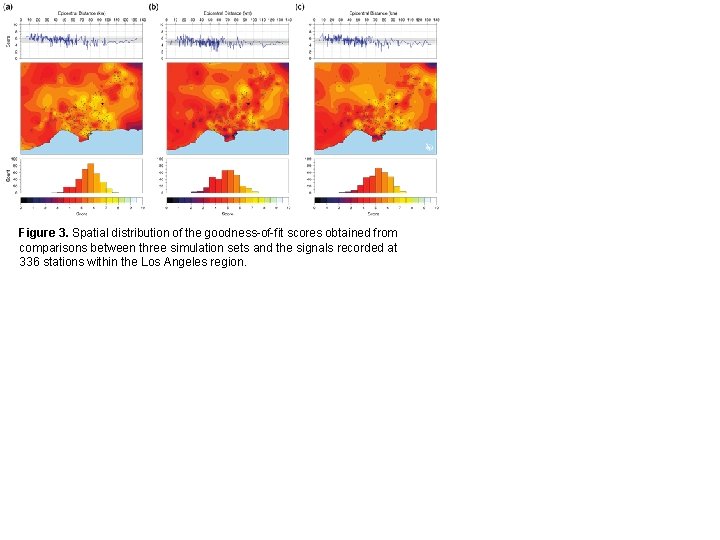

Figure 3. Spatial distribution of the goodness-of-fit scores obtained from comparisons between three simulation sets and the signals recorded at 336 stations within the Los Angeles region.

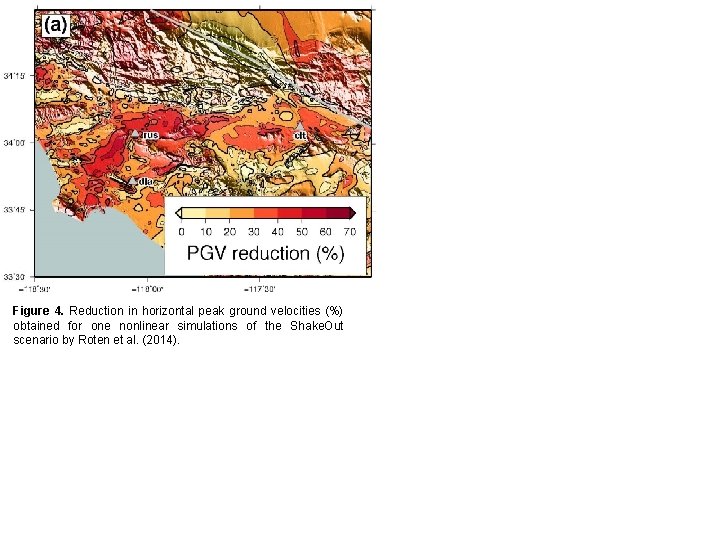

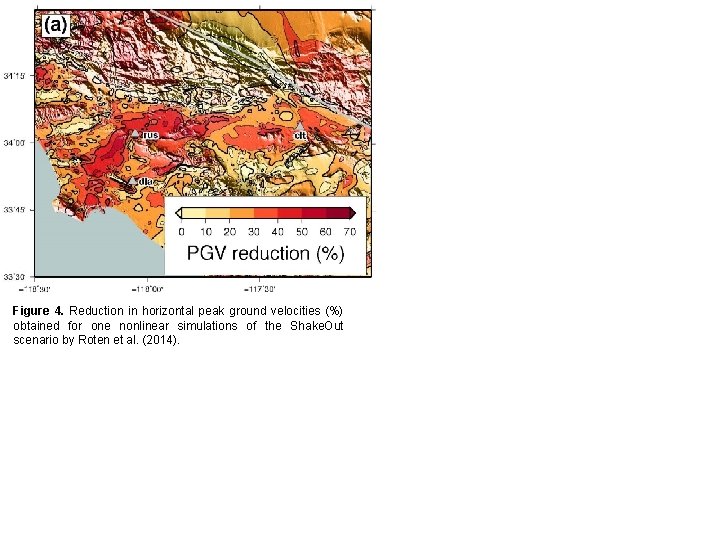

Figure 4. Reduction in horizontal peak ground velocities (%) obtained for one nonlinear simulations of the Shake. Out scenario by Roten et al. (2014).

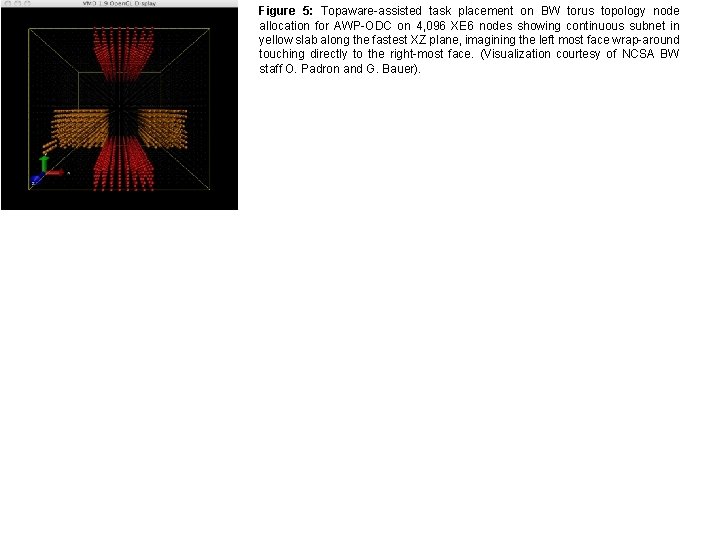

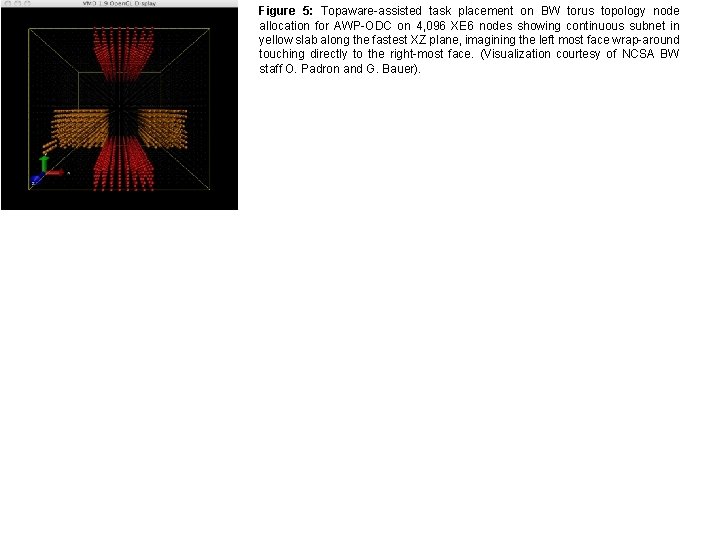

Figure 5: Topaware-assisted task placement on BW torus topology node allocation for AWP-ODC on 4, 096 XE 6 nodes showing continuous subnet in yellow slab along the fastest XZ plane, imagining the left most face wrap-around touching directly to the right-most face. (Visualization courtesy of NCSA BW staff O. Padron and G. Bauer).

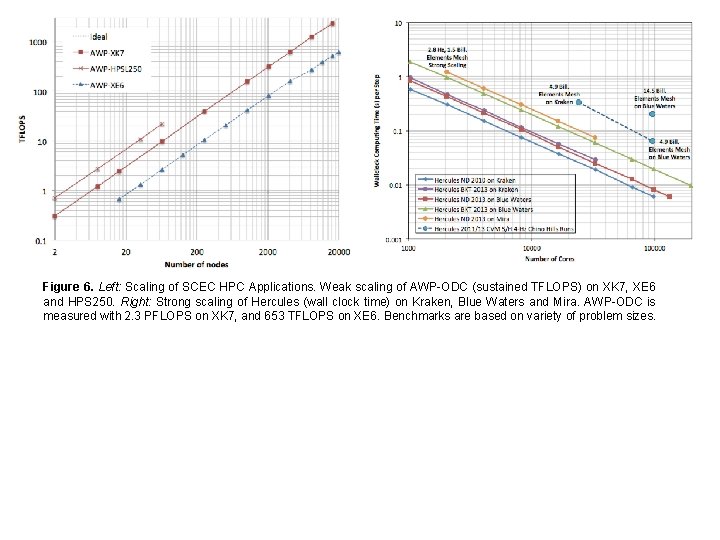

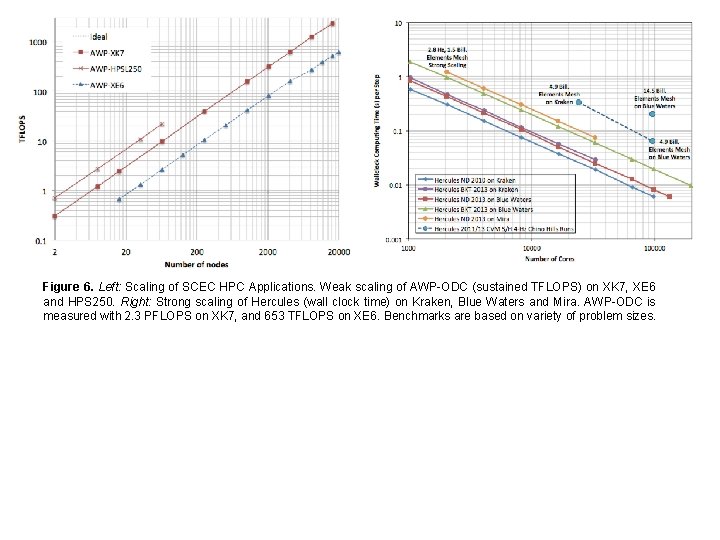

Figure 6. Left: Scaling of SCEC HPC Applications. Weak scaling of AWP-ODC (sustained TFLOPS) on XK 7, XE 6 and HPS 250. Right: Strong scaling of Hercules (wall clock time) on Kraken, Blue Waters and Mira. AWP-ODC is measured with 2. 3 PFLOPS on XK 7, and 653 TFLOPS on XE 6. Benchmarks are based on variety of problem sizes.

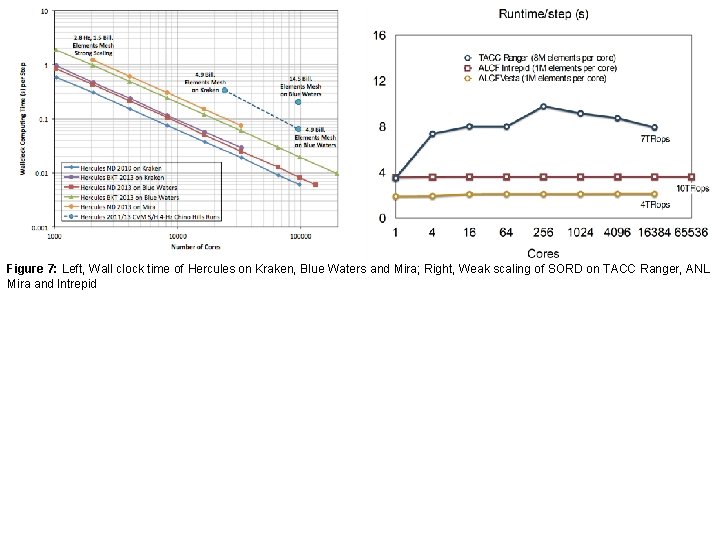

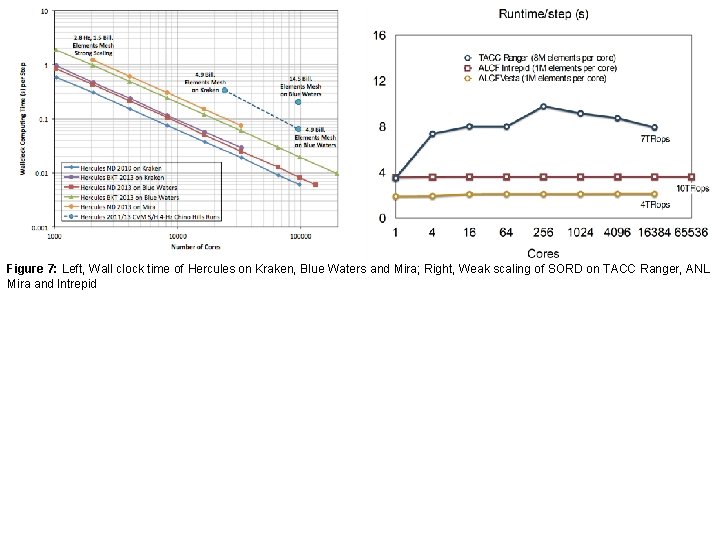

Figure 7: Left, Wall clock time of Hercules on Kraken, Blue Waters and Mira; Right, Weak scaling of SORD on TACC Ranger, ANL Mira and Intrepid