Failure Recovery Introduction Undo Logging Redo Logging Source

- Slides: 37

Failure Recovery Introduction Undo Logging Redo Logging Source: slides by Hector Garcia-Molina 1

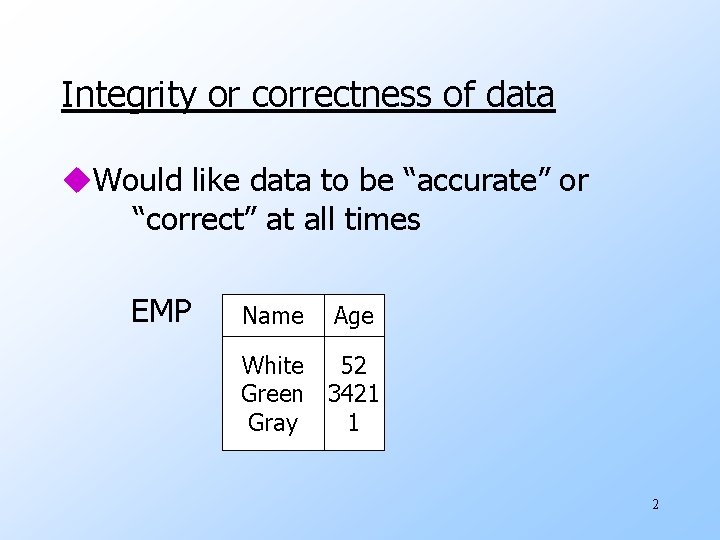

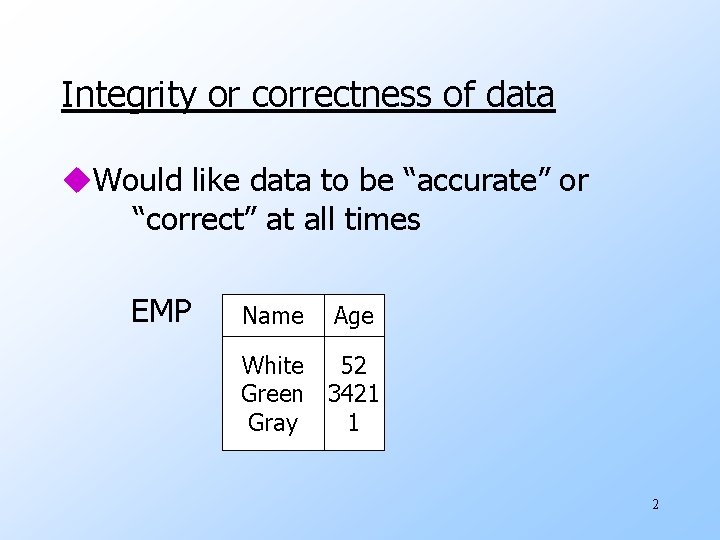

Integrity or correctness of data u. Would like data to be “accurate” or “correct” at all times EMP Name Age White 52 Green 3421 Gray 1 2

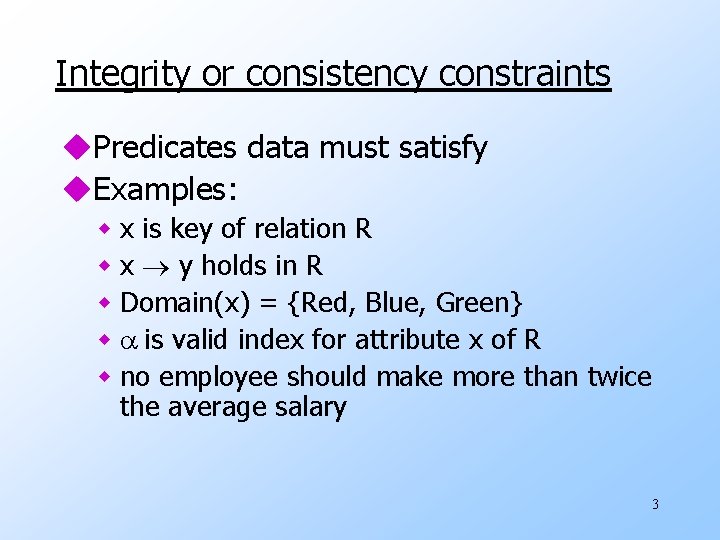

Integrity or consistency constraints u. Predicates data must satisfy u. Examples: w x is key of relation R w x y holds in R w Domain(x) = {Red, Blue, Green} w a is valid index for attribute x of R w no employee should make more than twice the average salary 3

Definition: u. Consistent state: satisfies all constraints u. Consistent DB: DB in consistent state 4

Constraints (as we use here) may not capture “full correctness” Example 1 Transaction constraints u. When salary is updated, new salary > old salary u. When account record is deleted, balance = 0 5

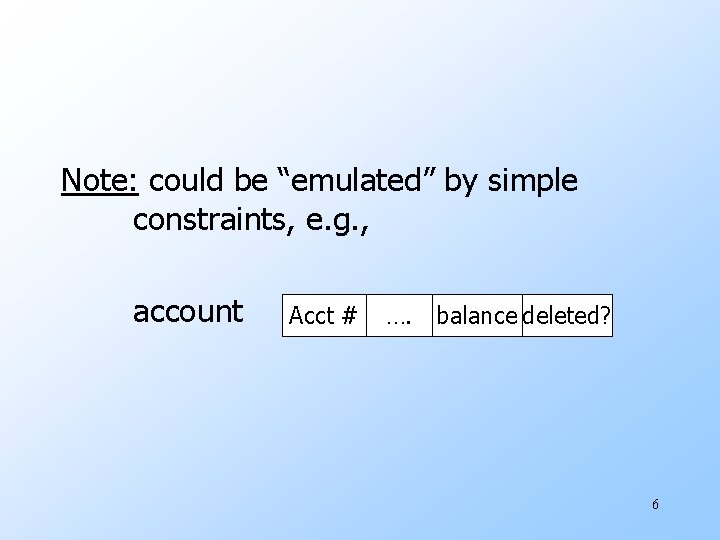

Note: could be “emulated” by simple constraints, e. g. , account Acct # …. balance deleted? 6

Constraints (as we use here) may not capture “full correctness” Example 2 DB Database should reflect real world Reality 7

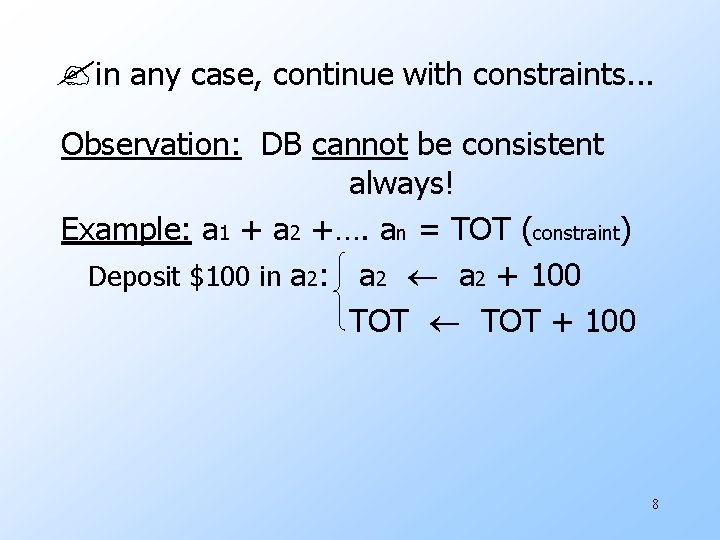

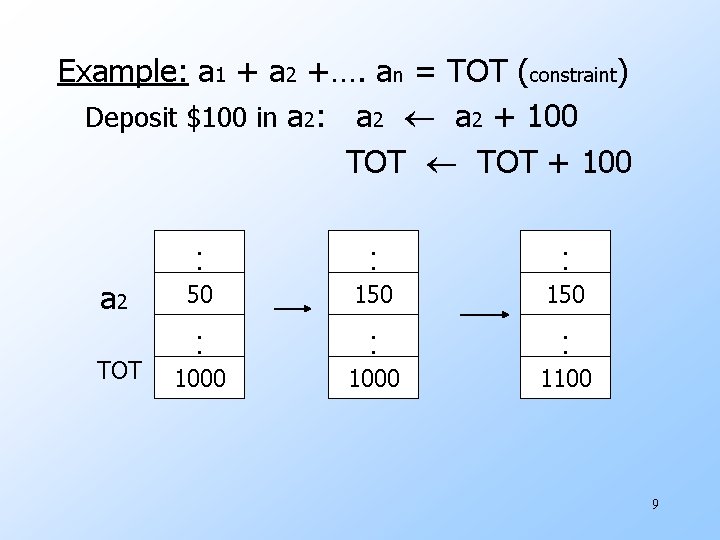

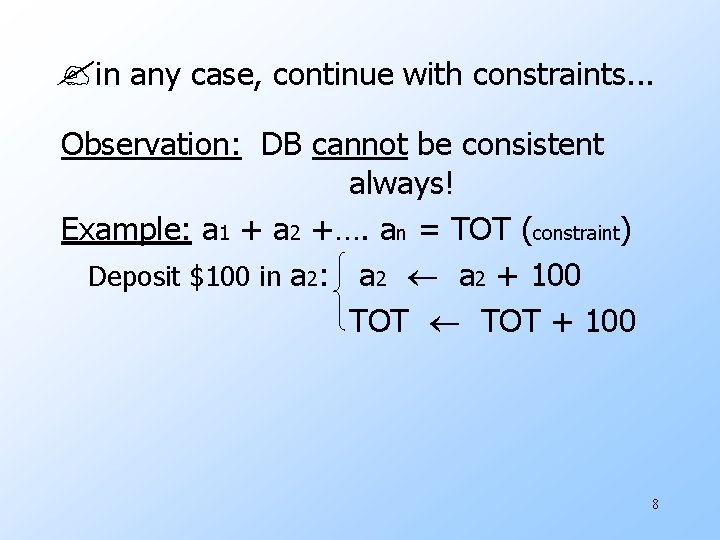

in any case, continue with constraints. . . Observation: DB cannot be consistent always! Example: a 1 + a 2 +…. an = TOT (constraint) Deposit $100 in a 2: a 2 + 100 TOT + 100 8

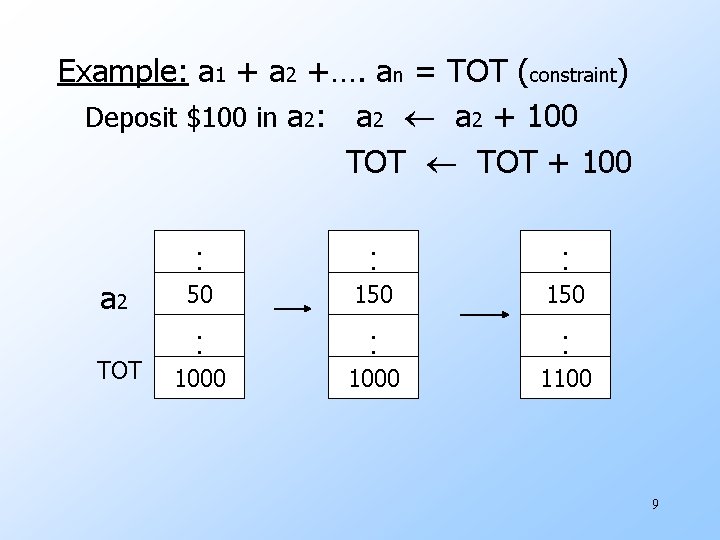

Example: a 1 + a 2 +…. an = TOT (constraint) Deposit $100 in a 2: a 2 + 100 TOT + 100 a 2 TOT . . 50 . . 150 . . 1000 . . 1100 9

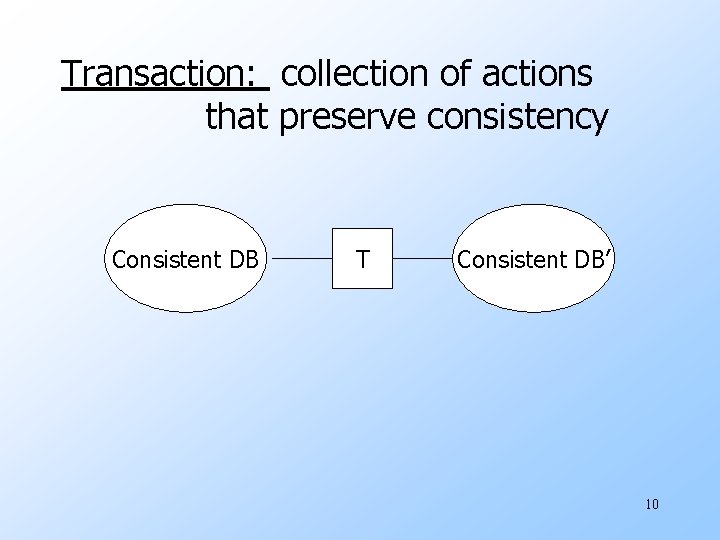

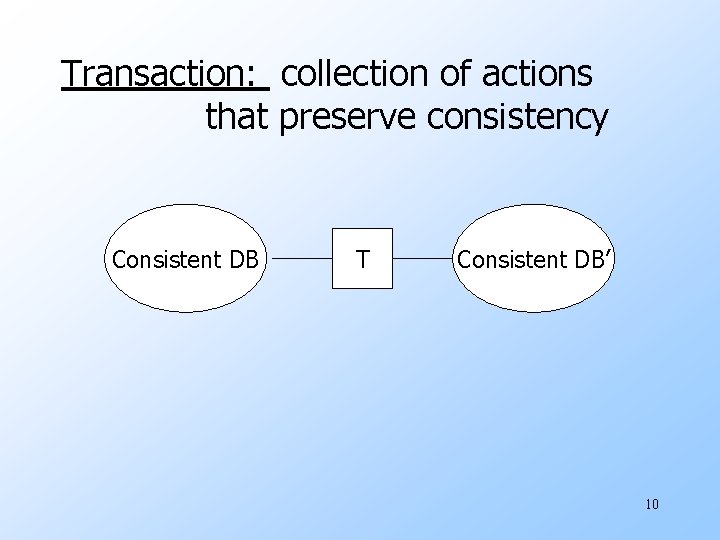

Transaction: collection of actions that preserve consistency Consistent DB T Consistent DB’ 10

Big assumption: If T starts with consistent state + T executes in isolation T leaves consistent state 11

Correctness (informally) u. If we stop running transactions, DB left consistent u. Each transaction sees a consistent DB 12

How can constraints be violated? u. Transaction bug u. DBMS bug u. Hardware failure e. g. , disk crash alters balance of account u. Data sharing e. g. : T 1: give 10% raise to programmers T 2: change programmers systems analysts 13

How can we prevent/fix violations? u. Chapter 17: due to failures only u. Chapter 18: due to data sharing only u. Chapter 19: due to failures and sharing 14

Will not consider: u. How to write correct transactions u. How to write correct DBMS u. Constraint checking & repair That is, solutions studied here do not need to know constraints 15

Chapter 17: Recovery u. First order of business: Failure Model 16

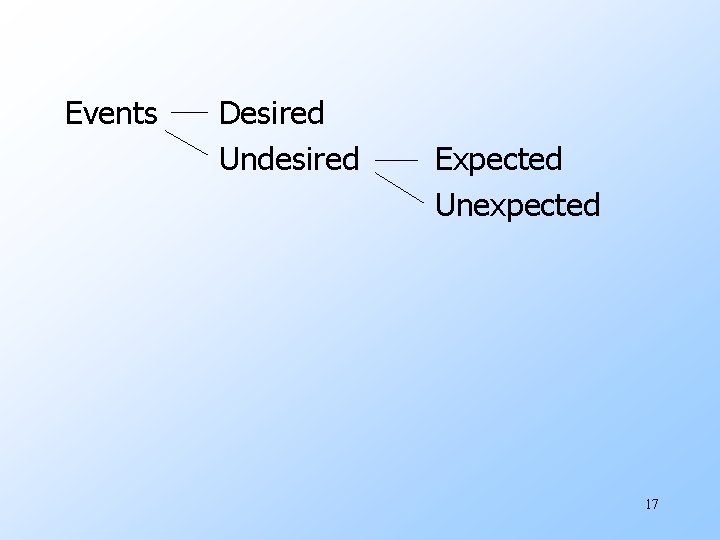

Events Desired Undesired Expected Unexpected 17

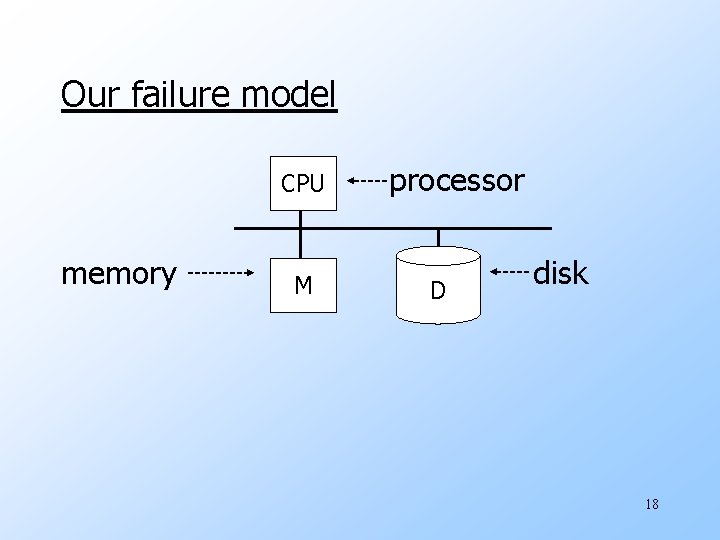

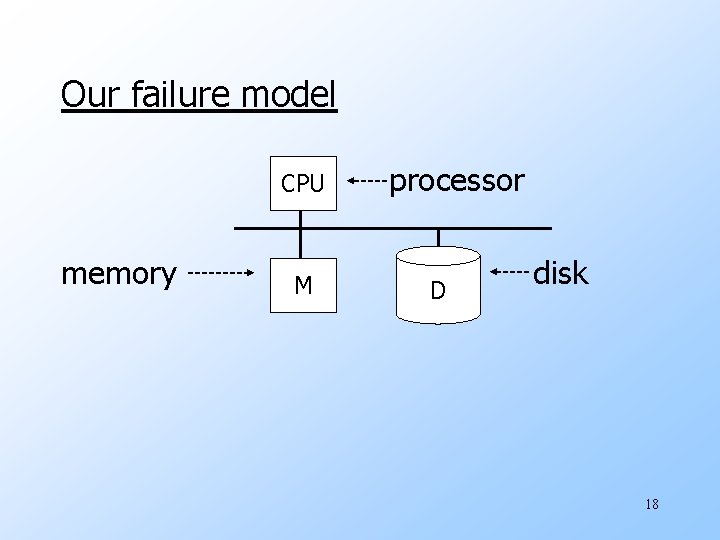

Our failure model CPU memory M processor D disk 18

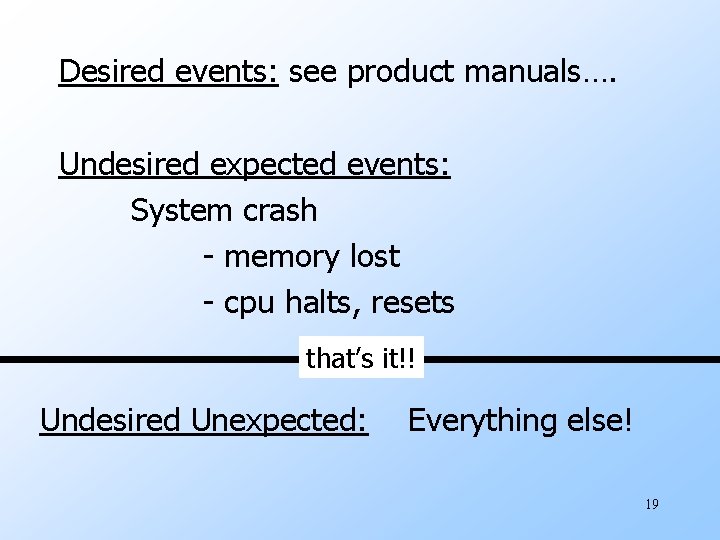

Desired events: see product manuals…. Undesired expected events: System crash - memory lost - cpu halts, resets that’s it!! Undesired Unexpected: Everything else! 19

Undesired Unexpected: Everything else! Examples: u. Disk data is lost u. Memory lost without CPU halt u. CPU implodes wiping out universe…. 20

Is this model reasonable? Approach: Add low level checks + redundancy to increase probability model holds E. g. , Replicate disk storage (stable store) Memory parity CPU checks 21

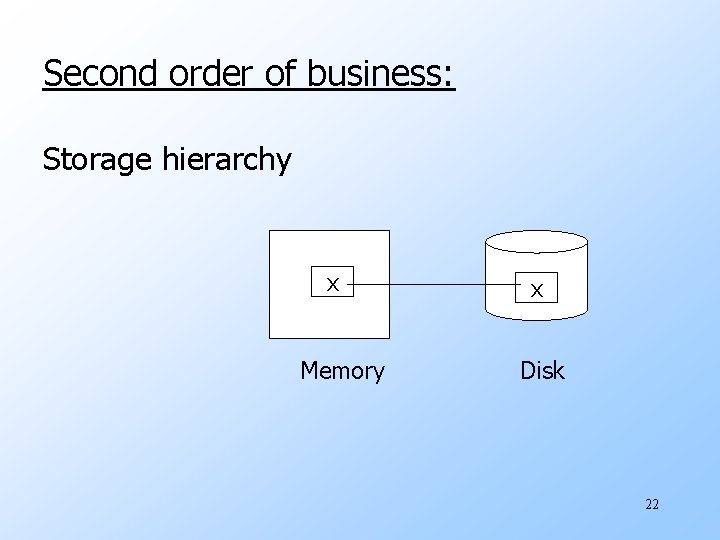

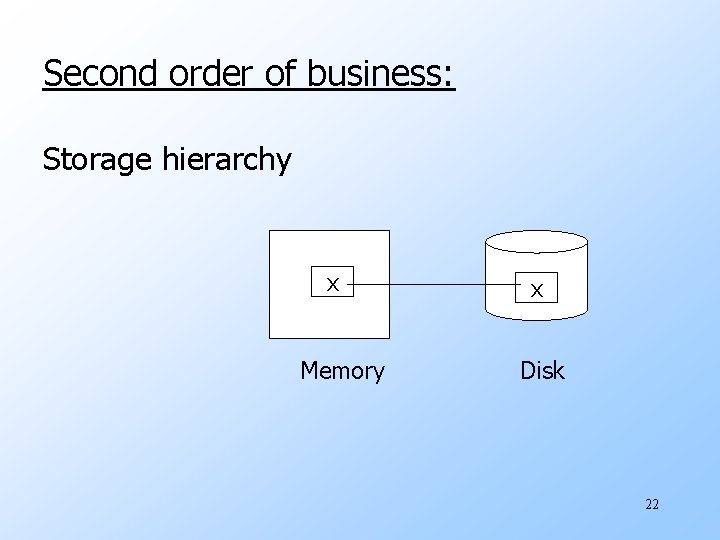

Second order of business: Storage hierarchy x Memory x Disk 22

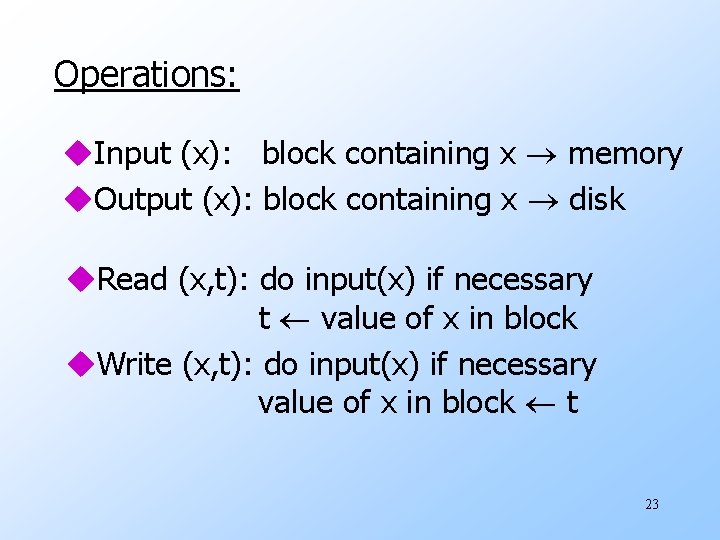

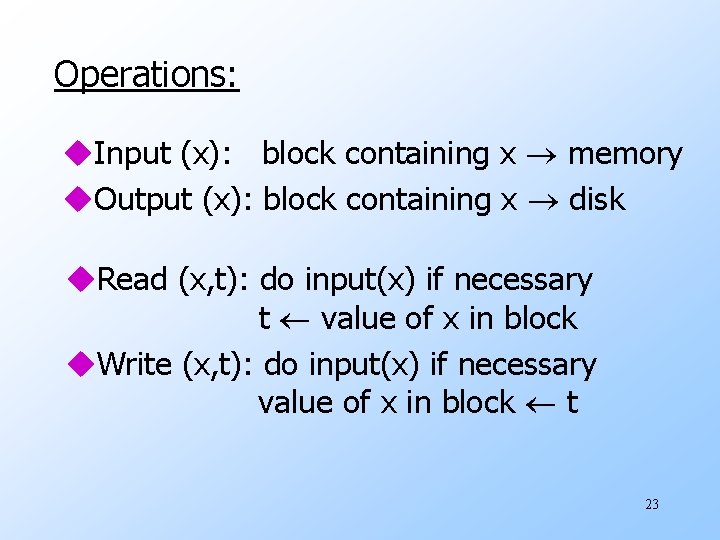

Operations: u. Input (x): block containing x memory u. Output (x): block containing x disk u. Read (x, t): do input(x) if necessary t value of x in block u. Write (x, t): do input(x) if necessary value of x in block t 23

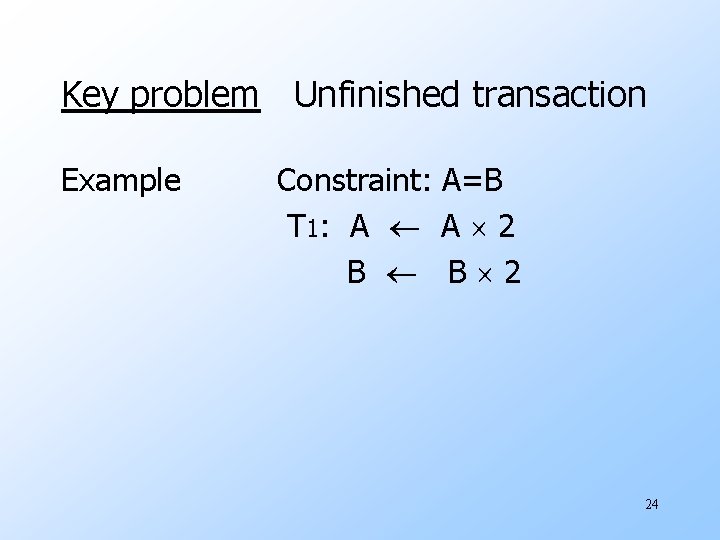

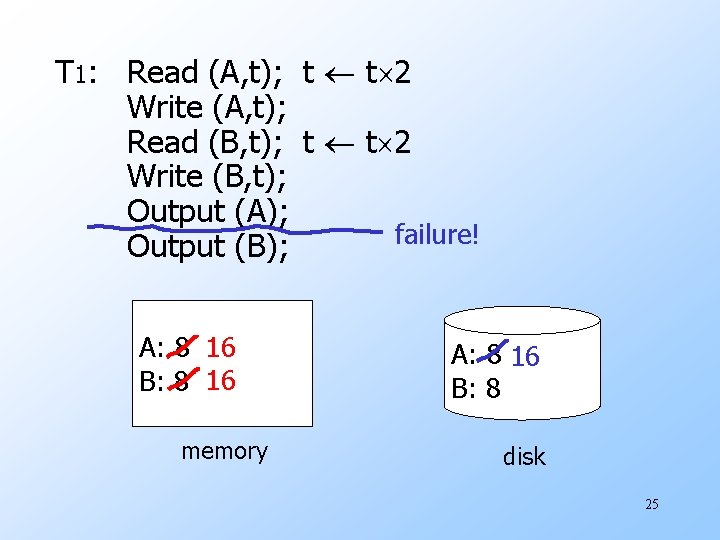

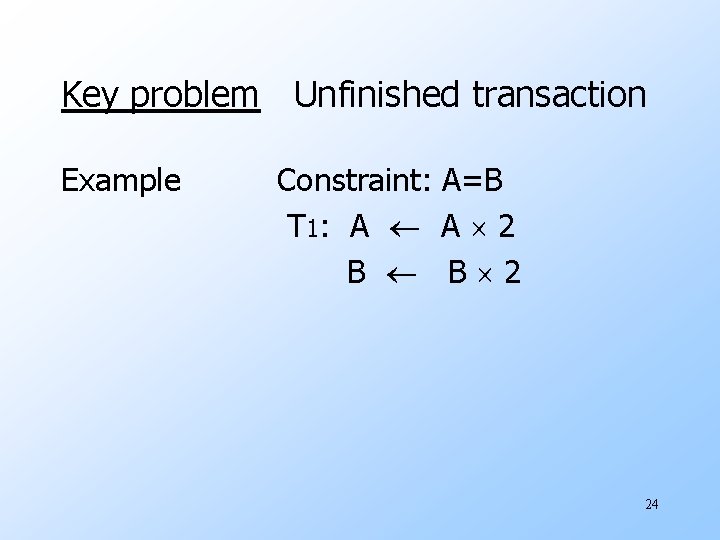

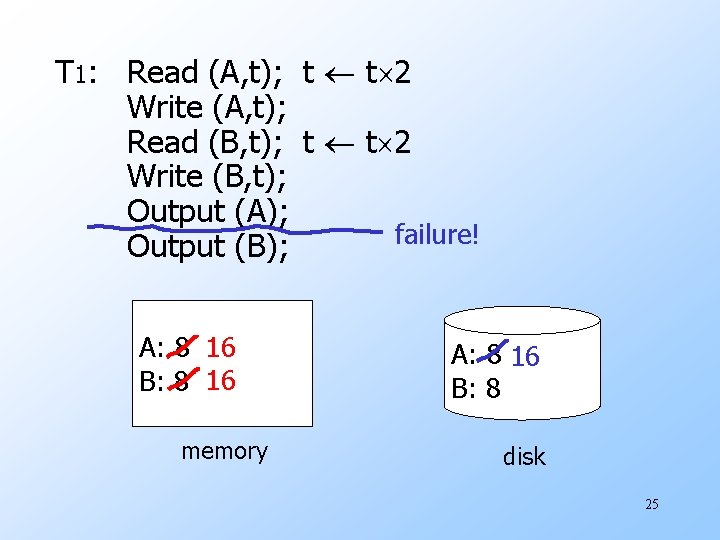

Key problem Unfinished transaction Example Constraint: A=B T 1: A A 2 B B 2 24

T 1: Read (A, t); t t 2 Write (A, t); Read (B, t); t t 2 Write (B, t); Output (A); failure! Output (B); A: 8 16 B: 8 16 memory A: 8 16 B: 8 disk 25

u. Need atomicity: execute all actions of a transaction or none at all 26

One solution: undo logging (immediate modification) due to: Hansel and Gretel, 782 AD u. Improved in 784 AD to durable undo logging 27

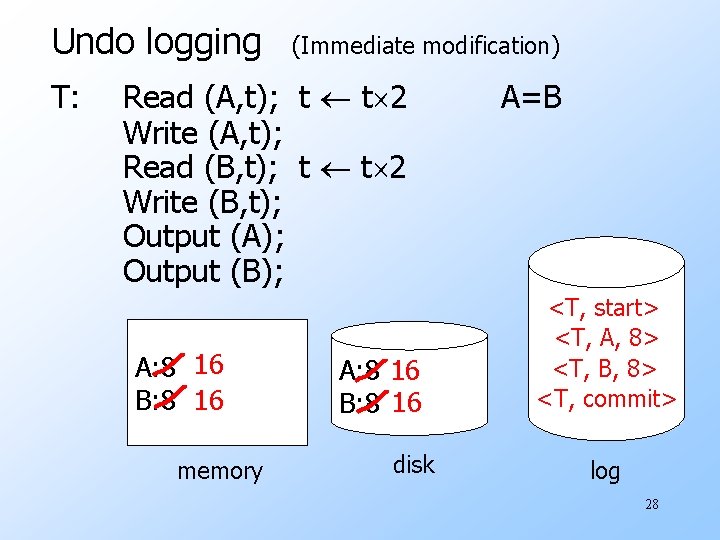

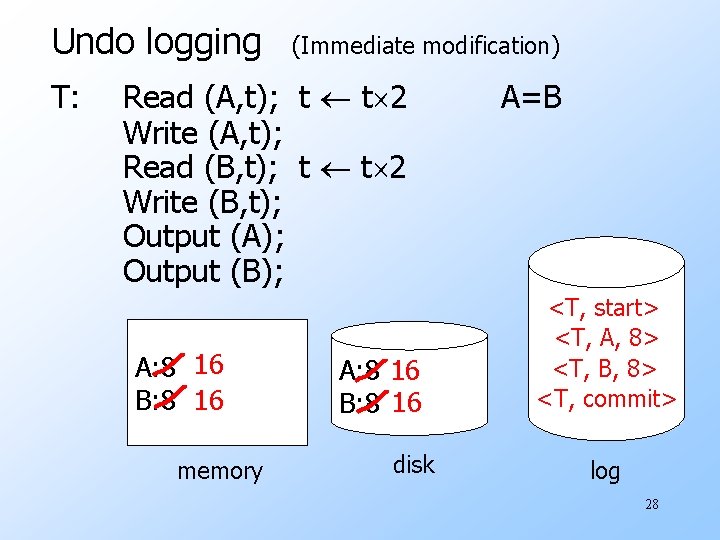

Undo logging T: (Immediate modification) Read (A, t); t t 2 Write (A, t); Read (B, t); t t 2 Write (B, t); Output (A); Output (B); A: 8 16 B: 8 16 memory A: 8 16 B: 8 16 disk A=B <T, start> <T, A, 8> <T, B, 8> <T, commit> log 28

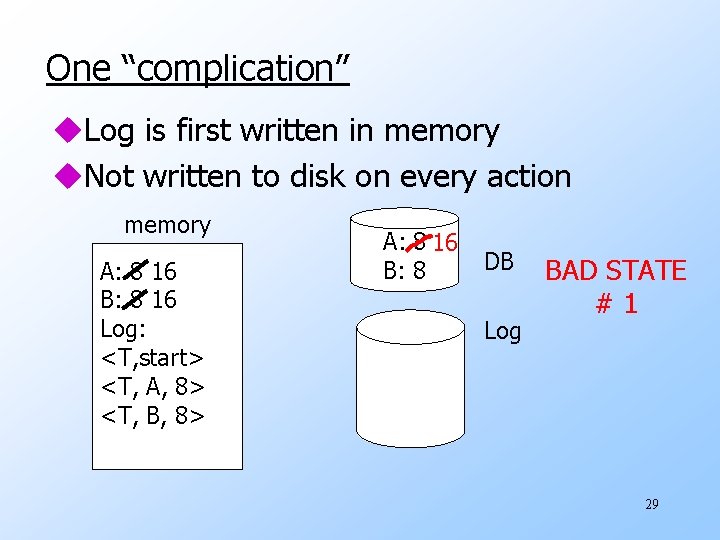

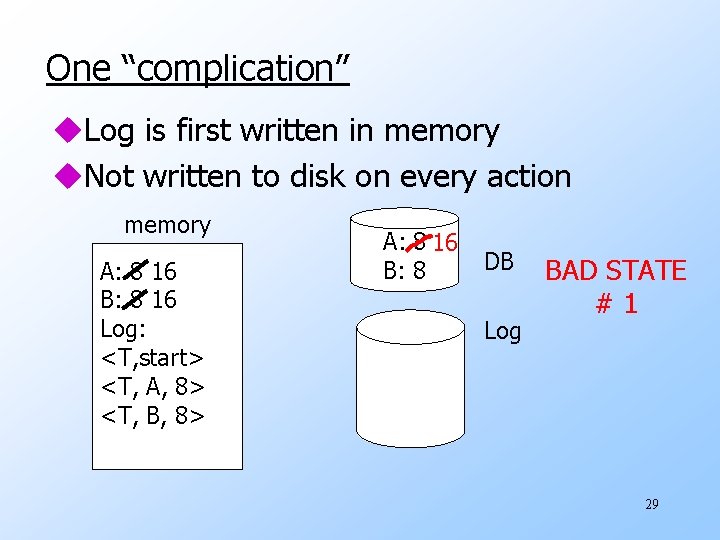

One “complication” u. Log is first written in memory u. Not written to disk on every action memory A: 8 16 B: 8 16 Log: <T, start> <T, A, 8> <T, B, 8> A: 8 16 B: 8 DB Log BAD STATE #1 29

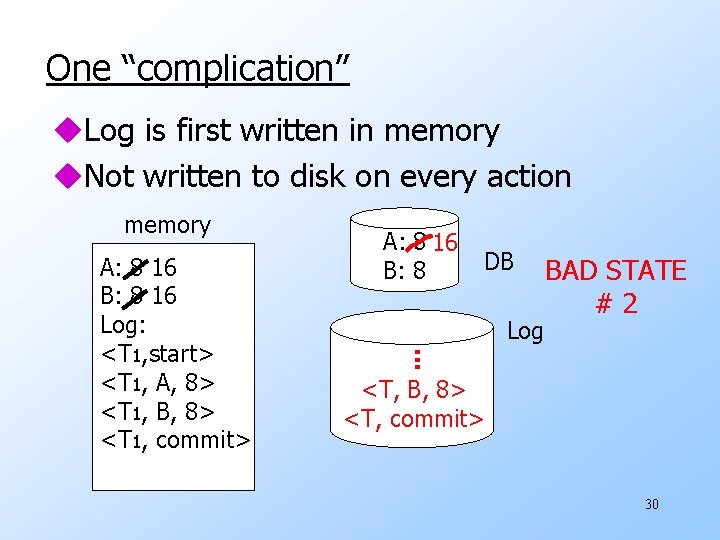

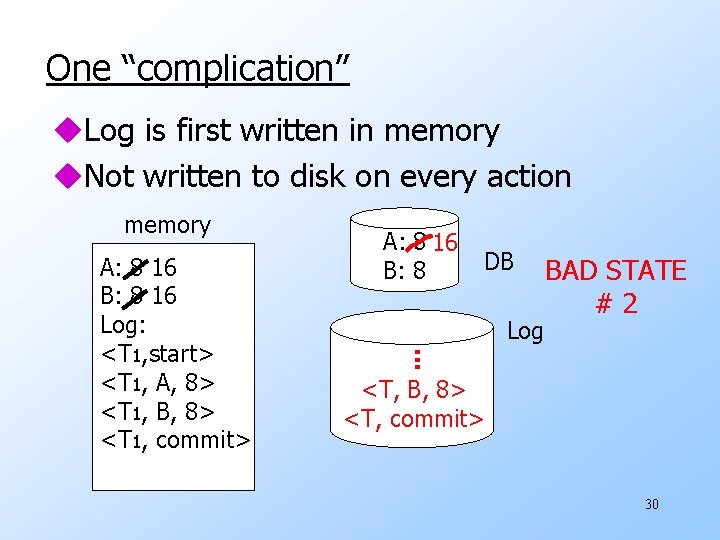

One “complication” u. Log is first written in memory u. Not written to disk on every action A: 8 16 B: 8 16 Log: <T 1, start> <T 1, A, 8> <T 1, B, 8> <T 1, commit> A: 8 16 B: 8 DB Log BAD STATE #2 . . . memory <T, B, 8> <T, commit> 30

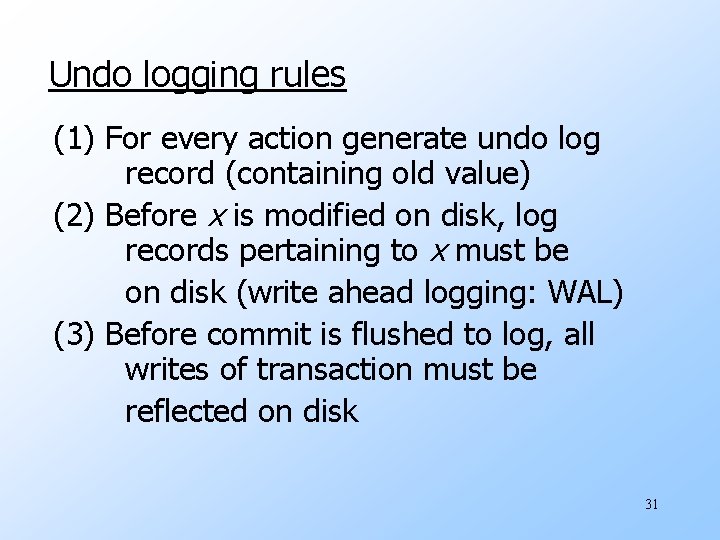

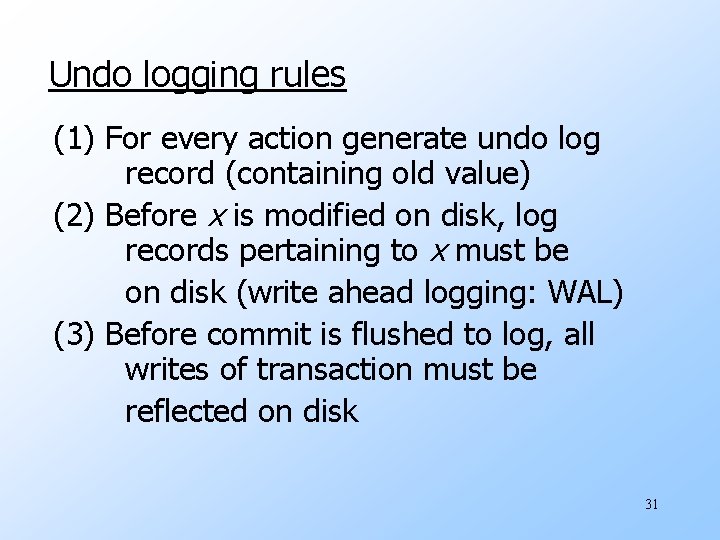

Undo logging rules (1) For every action generate undo log record (containing old value) (2) Before x is modified on disk, log records pertaining to x must be on disk (write ahead logging: WAL) (3) Before commit is flushed to log, all writes of transaction must be reflected on disk 31

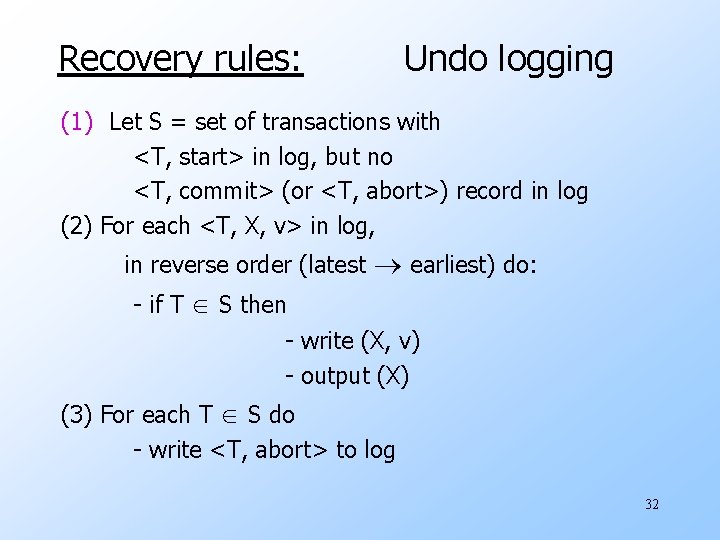

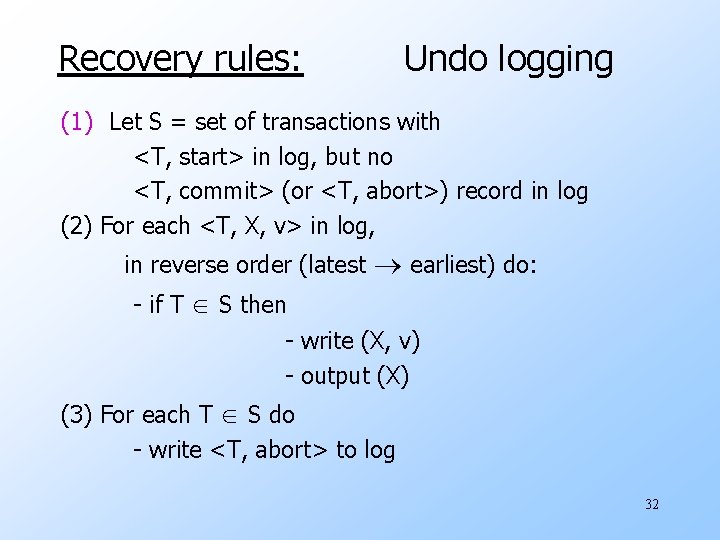

Recovery rules: Undo logging (1) Let S = set of transactions with <T, start> in log, but no <T, commit> (or <T, abort>) record in log (2) For each <T, X, v> in log, in reverse order (latest earliest) do: - if T S then - write (X, v) - output (X) (3) For each T S do - write <T, abort> to log 32

What if failure during recovery? No problem! Undo idempotent 33

To discuss: u. Redo logging u. Undo/redo logging, why both? u. Real world actions u. Checkpoints u. Media failures 34

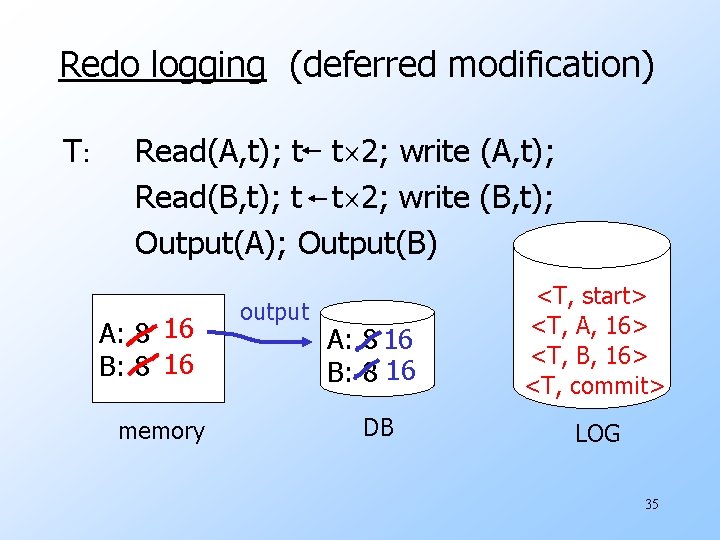

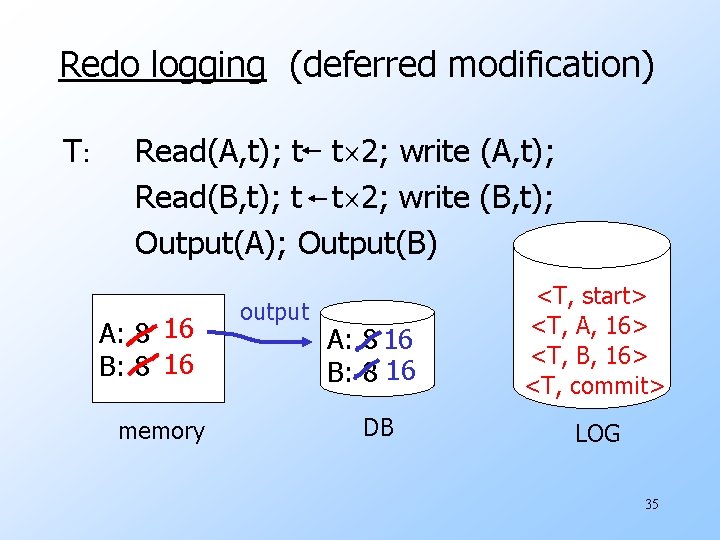

Redo logging (deferred modification) T: Read(A, t); t t 2; write (A, t); Read(B, t); t t 2; write (B, t); Output(A); Output(B) A: 8 16 B: 8 16 memory output A: 8 16 B: 8 16 <T, start> <T, A, 16> <T, B, 16> <T, commit> DB LOG 35

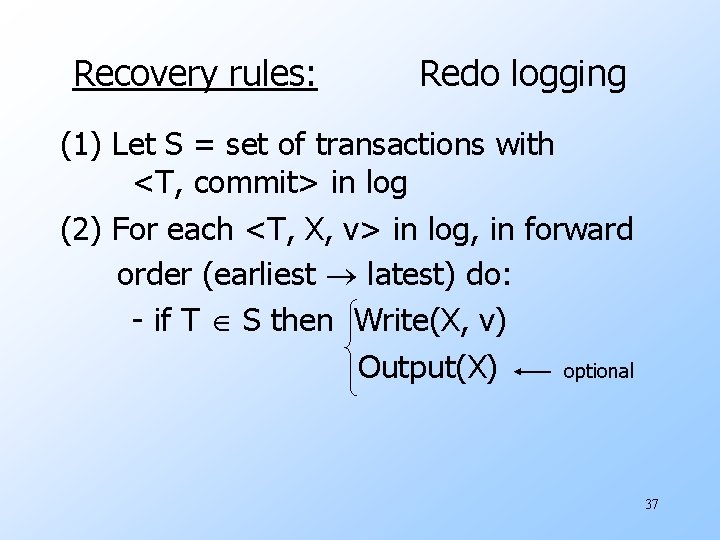

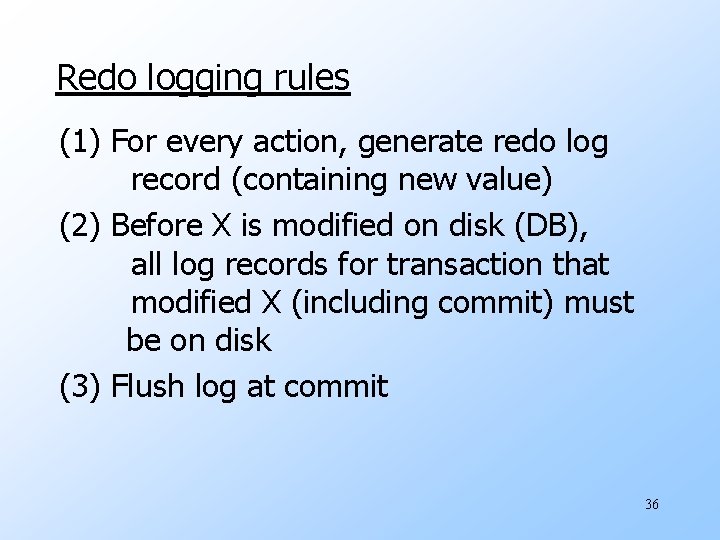

Redo logging rules (1) For every action, generate redo log record (containing new value) (2) Before X is modified on disk (DB), all log records for transaction that modified X (including commit) must be on disk (3) Flush log at commit 36

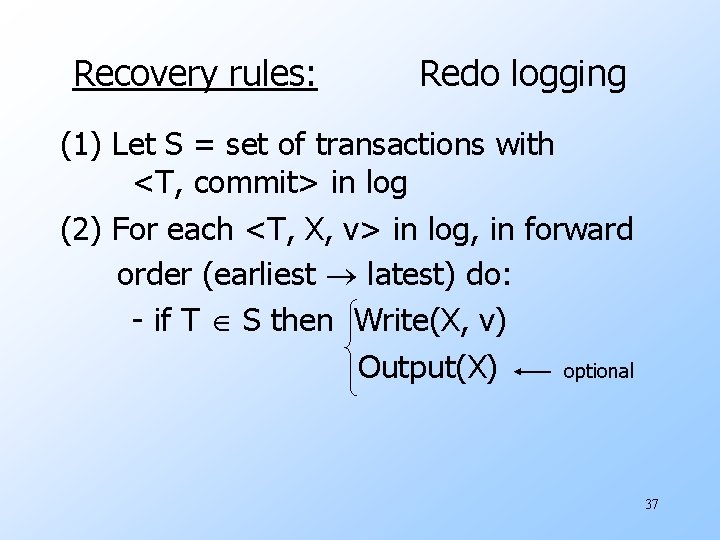

Recovery rules: Redo logging (1) Let S = set of transactions with <T, commit> in log (2) For each <T, X, v> in log, in forward order (earliest latest) do: - if T S then Write(X, v) Output(X) optional 37