EYITT Early Years Initial Teacher Training Graduate Employment

- Slides: 67

EYITT Early Years Initial Teacher Training Graduate Employment Based Programme CPLD Day 02 CHILD DEVELOPMENT

Objectives for the day • Review CPLD in Practice task 1 • To consider what is meant by learning • To link theories of child development to practice ( review preparation task 1) • To understand ‘Sustained Shared Thinking’ • To become familiar with the SSTEW • Discussion and Q&A on change projects and other tasks / assignments

Covered in this session REVIEW: • CPLD interim tasks 1 and 2 • • • Perceptions on learning Sustained Shared Thinking and related practice Theories of child development and related practice Cognitive development Development of language Maths rich environment

Theories/theorists- critical discussion REVIEW PREPARATION TASK 1 • In break out groups, take 5 minutes each to present your findings linked to your chosen theory / theorist and outline how this relates to your practice with babies, toddlers or young children

SSTEW item 10 • REVIEW PREPARATION TASK 2 -Developing a language rich environment STEWW ITEM 10 Learning walk Sub scale 4: Supporting learning and critical thinking Item 10: Encouraging sustained shared thinking through storytelling, sharing books, singing and rhymes In break out rooms compare – is there anything you could take back to improve this aspect of practice in your own setting?

• Theory 1: supporting the development of children’s learning

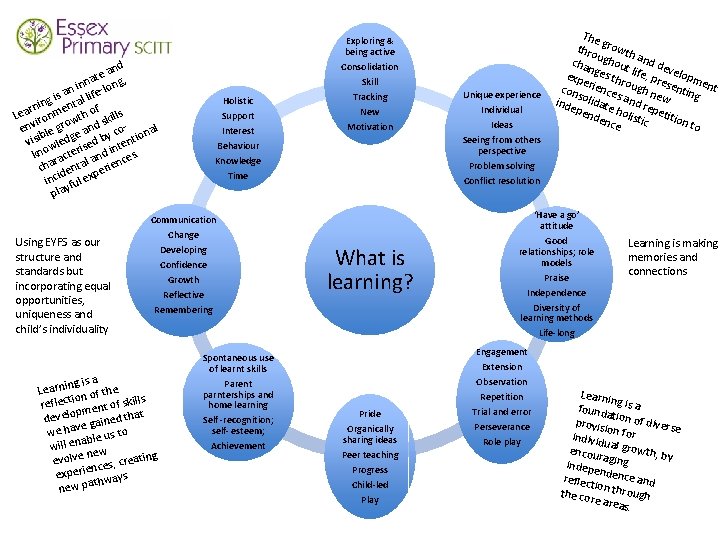

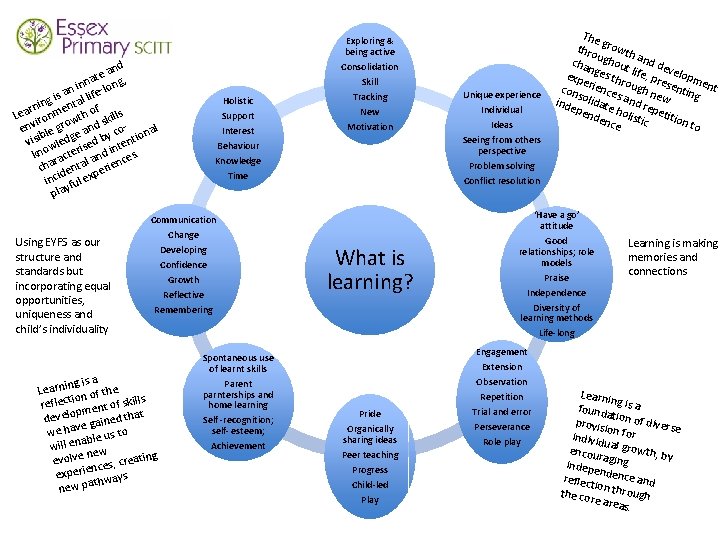

nd a e at , inn -long n a fe g is ntal li n f e r Lea ironm wth o skills env le gro e and co- nal b y o visi wledg ised b tenti n kno racter and i ces. l a a ch dent perien i inc ful ex y pla Holistic Support Interest Behaviour Knowledge Time Exploring & being active Consolidation Skill Tracking New Motivation Communication Using EYFS as our structure and standards but incorporating equal opportunities, uniqueness and child’s individuality Change Developing Confidence Growth Reflective Remembering ng is a Learni n of the io ls reflect of skil t n e m p develo gained that e v we ha le us to ab will en ew n evolve ces, creating en experi ys athwa new p Spontaneous use of learnt skills Parent parnterships and home learning Self -recognition; self- esteem; Achievement What is learning? Unique experience Individual Ideas Seeing from others perspective Problem solving Conflict resolution The thro growth u cha ghout and de n exp ges th life, pr velopm r e e con rience ough n sentin ent soli s an g e inde date d re w h p pen den olistic etition ce. to ‘Have a go’ attitude Good relationships; role models Praise Independence Diversity of learning methods Life-long Learning is making memories and connections Engagement Pride Organically sharing ideas Peer teaching Progress Child-led Play Extension Observation Repetition Trial and error Perseverance Role play Learni ng founda is a ti provis on of divers ion e individ for ual gro w encou raging th, by indepe n reflect dence and io the co n through re area s.

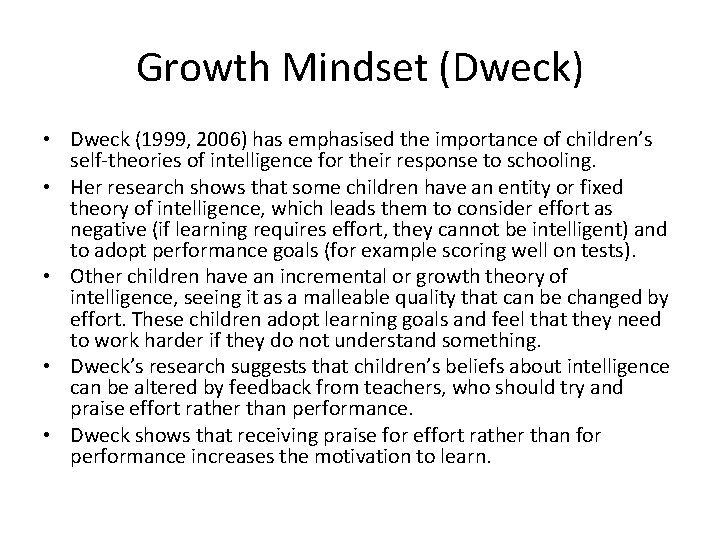

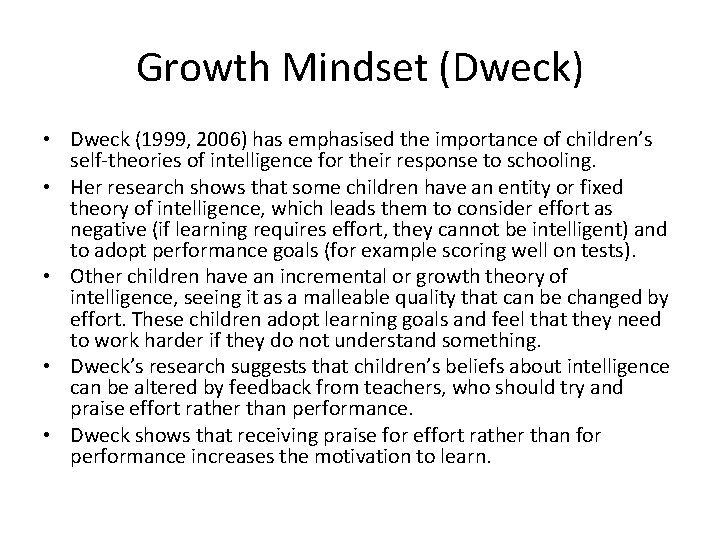

Growth Mindset (Dweck) • Dweck (1999, 2006) has emphasised the importance of children’s self-theories of intelligence for their response to schooling. • Her research shows that some children have an entity or fixed theory of intelligence, which leads them to consider effort as negative (if learning requires effort, they cannot be intelligent) and to adopt performance goals (for example scoring well on tests). • Other children have an incremental or growth theory of intelligence, seeing it as a malleable quality that can be changed by effort. These children adopt learning goals and feel that they need to work harder if they do not understand something. • Dweck’s research suggests that children’s beliefs about intelligence can be altered by feedback from teachers, who should try and praise effort rather than performance. • Dweck shows that receiving praise for effort rather than for performance increases the motivation to learn.

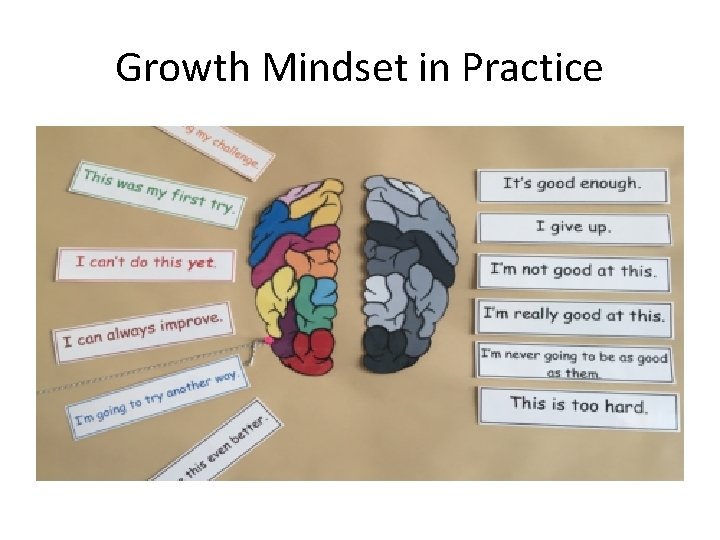

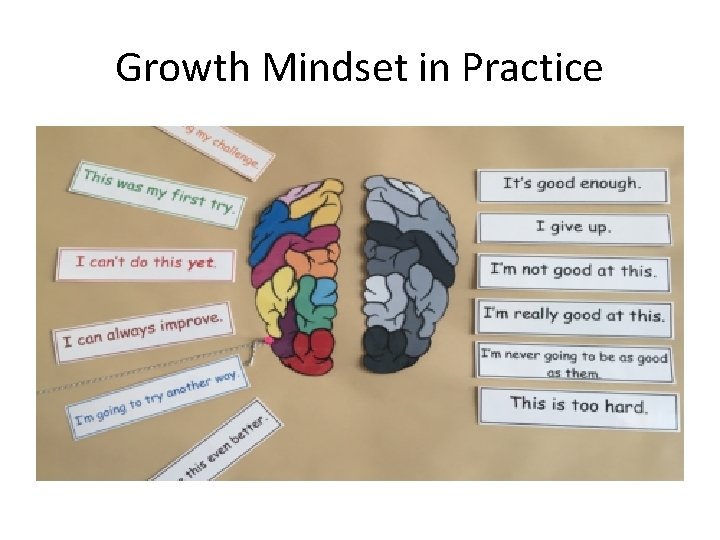

Growth Mindset in Practice

In the EYFS…

LEARNING (Braiswick Primary School) L is for… LEADING MY OWN LEARNING This is when learners believe in themselves as a learner and take responsibility over their own progress. This can be done through: • Being self motivated. Ask for and use feedback to further their learning. • Going beyond what is asked of them. For example, carrying out additional learning at home. • Taking responsibility when they don’t make progress, not blaming others for this. • Making decisions and choices to help with their learning. • Thinking carefully about what they need to do in their learning today. • Being organised and ready to learn. E is for… EMOTIONAL INTELLIGENCE This is when learners are aware of and can manage their own feelings as well as tuning into the feelings of others. This can be done through: • Recognise my own emotions and how they might make me behave. Know my own strengths and weaknesses. • Follow through on things that they agree to do. Take initiative. • Understand how other people behave and how they might be feeling. • Care about others as well as themselves. • Being able to embrace change and adapt to things around them. • Having dreams and ambitions.

LEARNING… A is for… ATTITUDES This is when learners can choose their own attitude, be positive and give their learning their full attention. This can be done through: • • • Choosing their own attitude. Always giving something their full attention. Having fun. Enjoy learning but understand that sometimes it is tough. Being kind and doing things for others that make them feel good. R is for… being RESOURCEFUL This is when learners use all of their skills, knowledge, strategies and tools to make meaning. This can be done through: • Using tools to help with their learning. • Using different strategies to help with their learning. • Using all the skills and knowledge they already have to support their learning.

LEARNING… N is for… NEURONS This is when learners use their brain to make connections and show that they are creative and divergent thinkers. This can be done through: • Using their brain to make connections. • Being methodical and coming up with systems and ways to work things out. • Being observant. Spotting patterns. Being creative and a divergent thinker. I is for… being INQUISITIVE This is when learners are curious and ask lots of questions. This can be done through: • Being curious about the world around them. • Asking questions to deepen their understanding. • Finding our new information to help support their learning.

LEARNING…. N is for… NEIGHBOURS This is when learners learn together, have good relationships and value each other’s ideas. This can be done through: • Sharing ideas with our learning neighbours or learning threes. • Helping others when they need it, Listening to and respecting others ‘ideas. G is for… GROWTH MINDSET This is when learners enjoy challenges, are resilient and learn from their mistakes. • This can be done through: • Seeing mistakes as learning opportunities. Being resilient—not giving up! Taking on challenges with enthusiasm.

Supporting Growth Mindset at home • Ask you child what they have been LEARNING not what they have been DOING. • Encourage inquisitiveness. Support them with homework. • Help build resilience by promoting Growth Mindset. . . • Encourage them to always try their best. Encourage them to challenge themselves and to keep trying even if they get stuck. • Reassure them that it is ok to take risks and make mistakes.

Sustained shared thinking • Standard: 2. 4 “ Lead and model effective strategies to develop and extend children’s learning and thinking, including sustained shared thinking (SST)” • “ High quality interactions helping children to make connections in their learning” • “ Can be planned or unplanned” • “ Capture children’s imaginations, clarify their ideas , ask questions and be creative”

What is Sustained Shared Thinking? An episode in which two or more individuals “work together” in an intellectual way to solve a problem, clarify a concept, evaluate activities, extend a narrative etc. Both parties must contribute to the thinking and it must develop and extend. Siraj. Blatchford et al. , REPEY, Df. ES 2002 » Look • • • Listen Note Observe body language; look at what they’re doing Listen to the dialogue Maintain eye contact What if? Pondering questions … “I wonder…” What else could we try? Thinking out loud Maybe…. . How can I encourage them to think critically? Get the environment right – especially important for pre-verbal children where SST is linked to sensory exploration Am I asking this question for myself or for the benefit of the child? – what is child gaining from the interaction?

• Practice 1: -SST transcript analysis In break out rooms • Which interaction is the most effective and why? • How could the least effective interaction be improved?

Author’s analysis (How do you know? ) Transcript 1: - • • • The boys are engaged in purposeful play. Play with which they are confident and familiar. They do not actually need adult intervention because they are achieving their own goals for their own purposes very successfully. The teacher does not stop and watch and listen before intervening. She presumes that the focus of the boys’ attention is on creating a ‘story’ around their castle. In fact they are simply ‘building’. They were enjoying the familiar routine of constructing what was quite a complex model and were also enjoying each other’s company. They had previously been engaged in a rather boisterous, whole group session of ‘Letters and Sounds’, and seemed to have returned to their castle for some quiet downtime, By speaking without tuning in to the boys’ play, the teacher interfered with both the mood of the play and its purpose. Because the teacher believed that asking questions would somehow enhance the learning she actually interfered with it. Firstly, she distracted the boys from their play by asking ‘What are you doing? ’, when some quiet observation would have answered that question. Then she persisted with a line of questioning that was attempting to manipulate the boys towards the purpose she had already assumed to be their purpose. She was not sufficiently sensitive to pick up that the boys were not responding with enthusiasm for or interest in the exchange, and that she had, in fact, stopped the play and taken its momentum away. She is uncomfortable with the boys’ lack of engagement with her and so fills the silences with further questions. Rather than be interrogated in this way, the boys chose to leave. What does the child/children gain?

Author’s analysis (How do you know? ) Transcript 2: • This transcript shows how attentive practitioners have to be to the twists and turns of children’s thinking and conversation. From snails to koalas to manicures to fingers being chopped off, this teacher moves effortlessly to follow the girls’ thinking and to make appropriate responses. Some of the teacher’s answers are complex. But she knows the girls well and can see they are listening. • In this instance, the girls have asked for an explanation, and therefore have a vested interest in the teacher’s answer. They also show their understanding by asking a follow-up question of their own ‘By the slime? ’ • The interaction between these two girls is sustained because of the close, warm relationship the practitioner has (the close body contact is evidence of that in that she doesn’t flinch or move away, for example, when the first child wipes paper over her ‘slimy’ forehead). • She tunes in to each change of theme; the problems she sets are genuine (‘I’ve got a lump on that finger…. What do you think you could do about that? ’). Her tone of voice is respectful and she treats the girls as conversational equals. • What does the child/children gain?

Laura • Laura is 12 months old and is just starting to use speech alongside non- verbal forms of communication. • Laura attends a Reggio Emilio inspired setting • It is just after lunch and all the other babies / toddlers are asleep

Laura’s learning • What was it? • What was the adult’s role?

Good Quality Reflection “How do you know? ” Why? Look Listen Note – get to know a child better and develop positive relationships with children and their parents – plan appropriate play and learning experiences based on the children’s interests and needs – and identify any concerns about a child’s development – further develop your understanding of a child’s development – develop a systematic and routine approach to using observations; – use assessment to plan the next steps in a child’s developmental progress and regularly review this approach. The Early Years Foundation Stage Practice Guidance © Crown copyright 2008

Co-regulation in learning and development • Emotional development before social development • Self-regulation – managing own emotions and intentions • Co-regulation - based on positive interactions that underpin ability to control behaviour, thoughts and feelings • ‘Transitional processes in a learner’s acquisition of SRL, during which members of a community share a common problem-solving plane, and SRL is gradually appropriated in response to and directed toward social and cultural contexts. ’* • ‘During co-regulatory activity, all participants assume expert and novice roles through varying aspects of the shared activity. ’* • Links to Zone of Proximinal Development (Vygotsky) – the difference between what we can do without help and what we can’t do without help – role of scaffolding *(Self-Regulation, Coregulation, and Socially Shared Regulation: Exploring Perspectives of Social in Self-Regulated Learning Theory. A Hadwin, M Oshige. University of Victoria (2011)

Self-regulation supported by Co-regulation ‘From co-regulation in the zone of proximal development emerge (a) self-regulation (adaptive learning, motivation, and identity), and (b) social and cultural enrichment. ’ Self-regulation: ‘There is extensive evidence (Rosenthal & Zimmerman, 1978) that adult models withdraw their support as observing youngsters display emulative accuracy. Reciprocally, these youngsters, seeing their increased proficiency, seek to perform on their own, such as when a young boy spurns further assistance from his mother when he feels he can tie his own shoelaces. At this point, the boy’s reliance on his mother as a social model becomes selective, and he will seek assistance from her mainly when he encounters obstacles, such as a novel type of shoelace. (Zimmerman, 2002, p. 5)’ Co-regulation: ‘The mother might ask questions like: What do you know about how to connect those two laces? How do you know when you have completed the first step properly? What do you need to do now? ’ (Self-Regulation, Coregulation, and Socially Shared Regulation: Exploring Perspectives of Social in Self-Regulated Learning Theory. A Hadwin, M Oshige. University of Victoria (2011)

Pre-verbal foundations for SST • • • Sustained eye contact between adult and child Sustained attention between adult and child Song and rhyme Peek-a-boo activities Treasure baskets – what are the properties of this object?

• Practice 2: -SST in action • Watch the following clip: Extending children’s ideas https: //youtu. be/byl. L-3 W 7 p. AI • In your group, outline the SST strategies (in SST log) used by the teacher • How effective are they?

SST task • Analysis of a simple transcript • Consider the elements of SST • Submission to Amanda James by 5: 00 pm 11/12/20 • Ensure you also complete the feedback task as an extra piece of portfolio evidence

Cognitive development and learning - Goswami Learning • Statistical learning by neural networks - The brain learns the statistical structure of experienced events, building neural networks to represent this information • Learning by imitation - babies as young as one hour old could imitate gestures like tongue protrusion and mouth opening after watching an adult produce the same gestures. • Learning by analogy - noticing similarities between one situation and another, or between one problem and another. This similarity then becomes a basis for applying analogous solutions. • Causal learning – infants see a variety of instantiations of a particular phenomenon, such as objects falling, and need to work out what causes them to fall. Knowledge construction • Nai ve physics - Perception organises itself fairly rapidly around a core framework representing the arrangement of cohesive, solid, three-dimensional objects which are embedded in a series of mechanical relations such as pushing, blocking and support • Nai ve biology - Children learn that things that move on their own are animate agents, and that their movements are not predictable but are caused by their own internal states • Nai ve psychology and ‘theory of mind’ - they learn the correlations and conditional probabilities embedded in the human behaviour around them, for example the kinds of events that lead to happiness or to anger • Cognitive neuroscience: the mirror neuron system - Mirror neurons were found to activate when the monkey performed object-directed actions such as tearing, grasping, holding and manipulating, and the same neurons also fired when the animal observed someone else performing the same class of actions.

Continued……. Memory • The development of episodic memory - Remembering is embedded in larger social and cognitive activities, and therefore the knowledge structures that young children bring to their experiences are a critical factor in explaining memory development and learning. • Working memory - Working memory (WM) is a limited capacity ‘workspace’ that maintains information temporarily while it is processed for use in other cognitive tasks, such as reasoning, comprehension and learning Pretend play and the imagination • The development of pretend play imagination - Pretending develops during the second year of life, with early pretence typically tied to the veridical actions that people make on objects (for example a 12 -month-old ‘drinking’ from an empty cup) and later pretence being more detached from object identities (for example a 2 -year-old pretending a stick is a horse) • The role of the imagination in cognitive development - While Western psychology has focussed on the important role of imaginative play in enabling a deeper understanding of mind (social cognitive development), Russian psychology has emphasised effects on cognitive selfregulation (executive function, see 6). Vygotsky (1978) argued that the imagination represented a specifically human form of cognitive activity. According to his theory, a central developmental function of pretend play was that children had to act against their immediate impulses and follow the ‘rules of the game’. Metacognition and executive function - Metacognition is knowledge about cognition, encompassing factors such as knowing about your own information-processing skills, monitoring your own cognitive performance, and knowing about the demands made by different kinds of cognitive tasks. Executive function refers to gaining strategic control over your own mental processes, inhibiting certain thoughts or actions, and developing conscious control over your thoughts, feelings and behaviour. • The development of metamemory - children’s awareness of themselves as memorisers, for example their awareness of their strengths and weaknesses in remembering certain types of information • The development of inhibitory control - strategic control over behaviour and of the inhibition of inappropriate behaviours. Inductive and deductive reasoning • Deductive reasoning - Deductive reasoning problems have only one logically valid answer • Inductive reasoning - he most important constraint on inductive reasoning is similarity

Implications for practice • • • Learning in young children is socially mediated. Families, peers and teachers are all important. Even basic perceptual learning mechanisms such as the statistical learning of linguistic sounds requires direct social interaction to be effective. This limits the benefits of educational approaches such as e-learning in the early years. Learning by the brain depends on the development of multi-sensory networks of neurons distributed across the entire brain. For example, a concept in science may depend on neurons being simultaneously active in visual, spatial, memory, deductive and kinaesthetic regions, in both brain hemispheres. Ideas such as left-brain/right-brain learning, or unisensory ‘learning styles’ (visual, auditory or kinaesthetic) are not supported by the brain science of learning. Children construct explanatory systems to understand their experiences in the biological, physical and psychological realms. These are implicit causal frameworks, for example that explain why other people behave as they are observed to do, or why objects or events follow observed patterns. Knowledge gained through active experience, language, pretend play and teaching are all important for the development of children’s causal explanatory systems. Children’s causal biases (eg. the essentialist bias) should be recognised and built upon in primary education.

Continued…. • • • Children think and reason largely in the same ways as adults. However, they lack experience, and they are still developing important metacognitive and executive function skills. Learning in classrooms can be enhanced if children are given diverse experiences and are helped to develop self-reflective and self-regulatory skills via teacher modelling, conversation and guidance around social situations like play, sharing and conflict resolutions. Language is crucial for development. The ways in which teachers talk to children can influence learning, memory, understanding and the motivation to learn. There also enormous individual differences in language skills between children in the early years. Interactions around books are one of the best ways of developing more complex language skills. Incremental experience is crucial for learning and knowledge construction. The brain learns the statistical structure of ‘the input’. It can be important for teachers to assess how much ‘input’ a child’s brain is actually getting when individual differences appear in learning. Differential exposure (for example to spoken or written language) will lead to differential learning. As an example, one of the most important determinants of reading fluency is how much text the child actually reads, including outside the classroom. Thinking, reasoning and understanding can be enhanced by imaginative or pretend play contexts. However, scaffolding by the teacher is required if these are to be effective. Individual differences in the ability to benefit from instruction (the zone of proximal development) and individual differences between children are large in the primary years, hence any class of children must be treated as individuals.

• Practice 3: -Interacting or interfering? • An interview with Julie Fisher • What are the key messages for you from this interview?

Lunch

• Theory 2: - Attachment theory • Standard 2. 3: Know and understand attachment theories, their significance and how effectively to promote secure attachments • EYT’s recognise the relevance of attachment theory and it’s significance • Work together with parents / carer’s through a key person approach • Each child feels emotionally secure

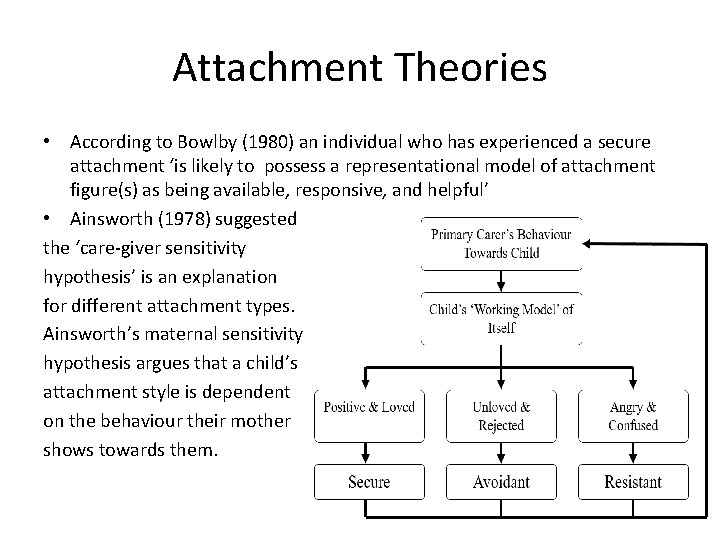

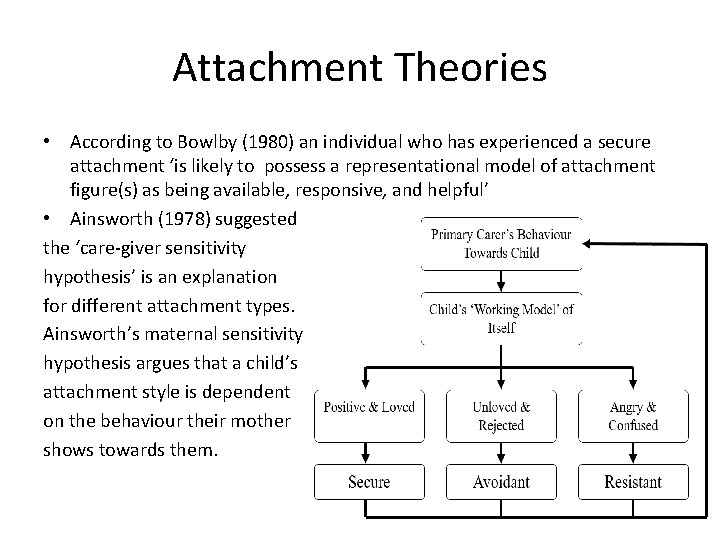

Attachment Theories • According to Bowlby (1980) an individual who has experienced a secure attachment ‘is likely to possess a representational model of attachment figure(s) as being available, responsive, and helpful’ • Ainsworth (1978) suggested the ‘care-giver sensitivity hypothesis’ is an explanation for different attachment types. Ainsworth’s maternal sensitivity hypothesis argues that a child’s attachment style is dependent on the behaviour their mother shows towards them.

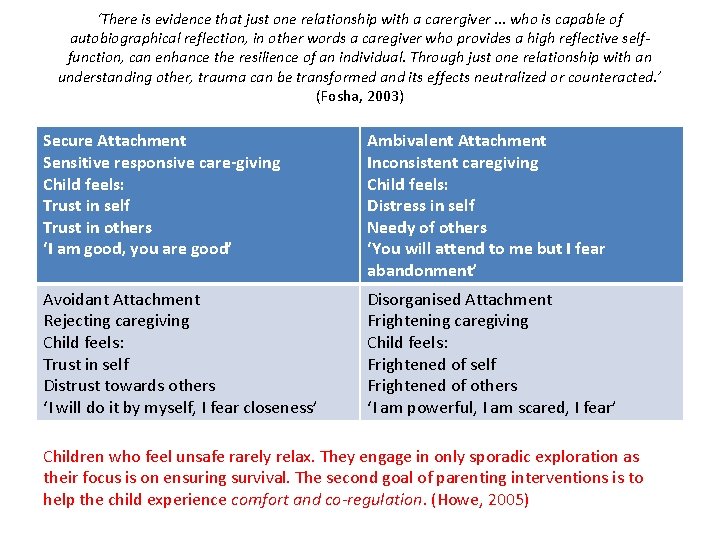

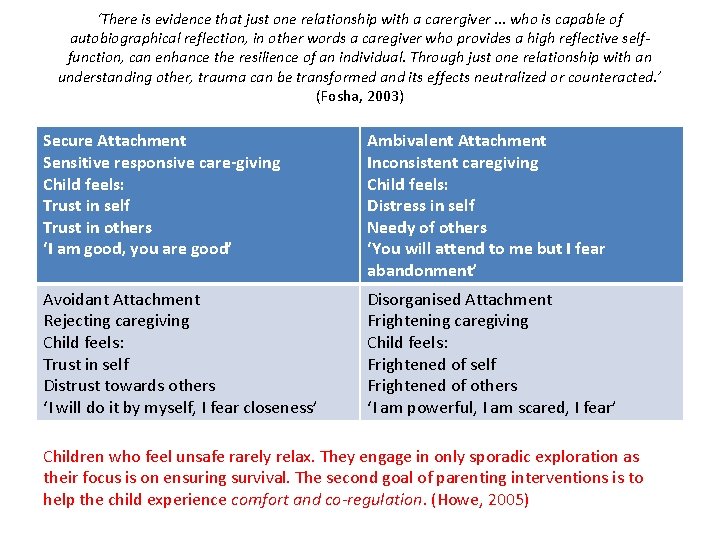

‘There is evidence that just one relationship with a carergiver. . . who is capable of autobiographical reflection, in other words a caregiver who provides a high reflective selffunction, can enhance the resilience of an individual. Through just one relationship with an understanding other, trauma can be transformed and its effects neutralized or counteracted. ’ (Fosha, 2003) Secure Attachment Sensitive responsive care-giving Child feels: Trust in self Trust in others ‘I am good, you are good’ Ambivalent Attachment Inconsistent caregiving Child feels: Distress in self Needy of others ‘You will attend to me but I fear abandonment’ Avoidant Attachment Rejecting caregiving Child feels: Trust in self Distrust towards others ‘I will do it by myself, I fear closeness’ Disorganised Attachment Frightening caregiving Child feels: Frightened of self Frightened of others ‘I am powerful, I am scared, I fear’ Children who feel unsafe rarely relax. They engage in only sporadic exploration as their focus is on ensuring survival. The second goal of parenting interventions is to help the child experience comfort and co-regulation. (Howe, 2005)

• Practice 3: - Strategies to support attachment behaviours Activity: • In your groups, discuss the attachment category assigned to you and outline strategies you might employ. • One member of each group feedback to all of us • Write comments in the ‘chat’ box if you have anything to add

• Theory 3: - Language and maths development

Language Development Chomsky Language Acquisition Device (LAD) • Chomsky's theory of Language Acquisition Device (LAD) is in contrast to Piaget’s theory in that he suggests that the knowledge of basic rules of language is by picking up on regularities and testing them out. • Each of these rules is part of the wider set of language rules connected to the child's specific culture through "surface structure" (order of words) and "deep structure" (meaning) (Smith et al. 2011). • Chomsky claims knowledge of language and its systems is innate and its structure culturally formed (Donaldson, 1978).

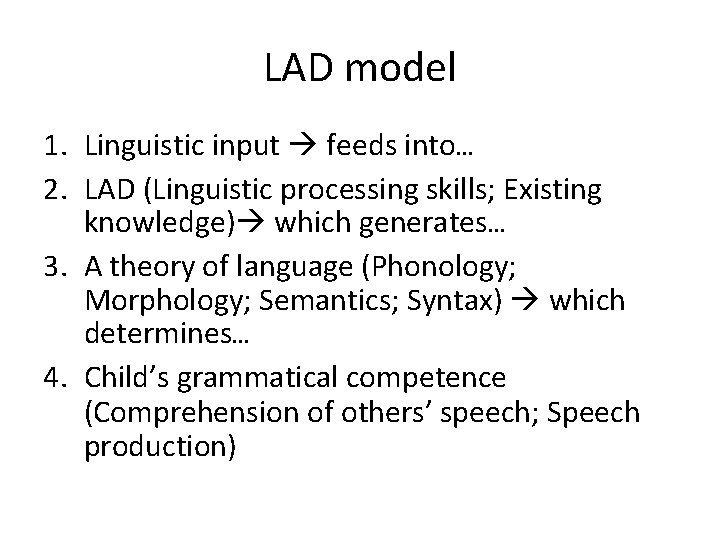

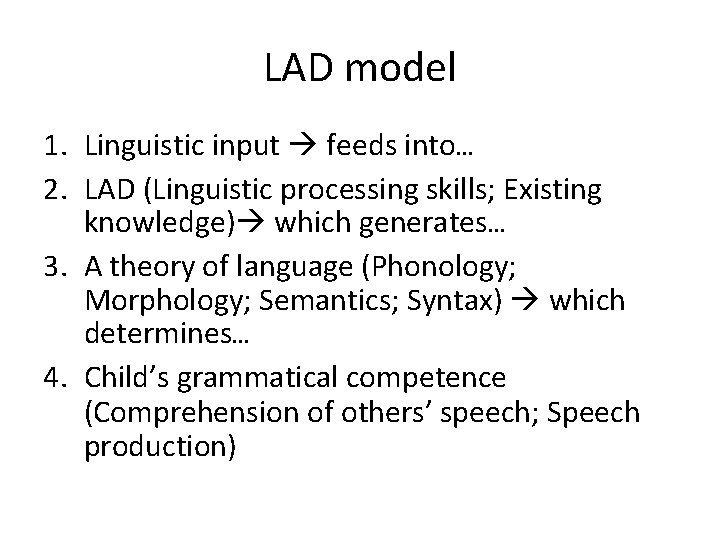

LAD model 1. Linguistic input feeds into… 2. LAD (Linguistic processing skills; Existing knowledge) which generates… 3. A theory of language (Phonology; Morphology; Semantics; Syntax) which determines… 4. Child’s grammatical competence (Comprehension of others’ speech; Speech production)

Sociocultural theories of language development • Bandura -Social Learning Theory: role of imitation , observation and copying • Vygotsky Socio cultural theory– Innate ability to learn language but must be exposed to variety of social experiences, interactions and play • Language is important means of transmitting knowledge externally and also as ‘inner speech’ to internalise thoughts

Vygotsky – language development in a social context • Key role in Vygotsky’s theory of cognitive development. Infants then use the same abilities to acquire the phonological (soundbased) aspects of language that they use to acquire knowledge about the physical and psychological worlds, namely associative learning, tracking statistical dependencies, tracking conditional probabilities and making analogies. *Goswami

Language development - Goswami • • Language aids conceptual development, the development of a theory of mind, episodic memory development, and is the basis of working memory Word learning is aided by the universal tendency of adults (and children) to talk to babies using a special prosodic register called infant-directed speech (IDS) or ‘Motherese’. IDS uses higher pitch and exaggerated intonation (for example increased duration and stress) to highlight novel information, which appears perceptually effective in facilitating learning (for example Fernald and Mazzie 1991). Children who are less sensitive to the auditory cues of the prosodic and rhythmic patterning in language may be at risk for developmental dyslexia and specific language impairment (for example Corriveau et al. 2007). Active production is also important for language acquisition, and babbling reflects early production of the structured rhythmic and temporal patterns of language. Deaf babies do not show typical vocal babble, however babies born to signing deaf parents will ‘sign babble’ with their hands, duplicating the rhythmic timing and stress patterning of hand shapes in natural sign languages (Pettito et al. 2004).

Continued…. Vocabulary development • The primary function of language is communication, and words are part of meaning-making experiences from very early in development. • Conceptual representations precede language development, being rooted in the perceptual experience of objects and events. Nevertheless, carers talk to babies before they can talk back, naming objects that are being attended to, commenting on joint activities or discussing the child’s behaviour or apparent feelings. • One study showed that toddlers hear an estimated 5000 – 7000 utterances a day, with around a third of these utterances being questions (Cameron- Faulkner et al. 2003). • In a U. S. study, Hart and Risley (1995) estimated that children from high socio-economic status (SES) families heard around 487 utterances per hour, compared to 178 utterances per hour for children from families on welfare. • Hence by the time they were aged 4 years, the high SES children had been exposed to around 44 million utterances, compared to 12 million utterances for the lower SES children. • Word learning is also important for cognitive development because it is symbolic. Words are symbols because they refer to an object or to an event, but they are not the object or the event itself. Symbols allow children to disconnect themselves from the immediate situation. • Gestures are also symbolic (for example waving ‘goodbye’). Gesture precedes language production in development, providing a ‘cognitive bridge’ between comprehension and production (Volterra and Erting 1990). Action is used to express meaning. Even later in cognitive development, gesture can provide important information about what the child understands in a given cognitive domain.

Brain break! Consider the following scenario and jot down the strategies you would use to keep calm and overcome: • You are starting a new job this morning with unfamiliar people and in a location you have only visited once for your interview • You have a 15 minute walk from your house to the train station for your 45 minute commute • 5 minutes into the walk, it begins to rain and you have no coat or umbrella • You arrive at the station to discover that your train has been cancelled and the next available train is in 30 minutes, which you have no option but to wait for • You anticipate that you will be approximately 20 minutes late to your new place of work

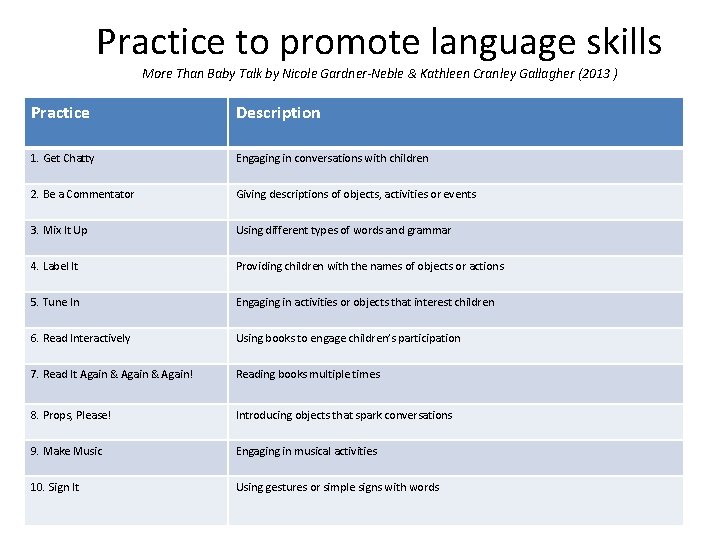

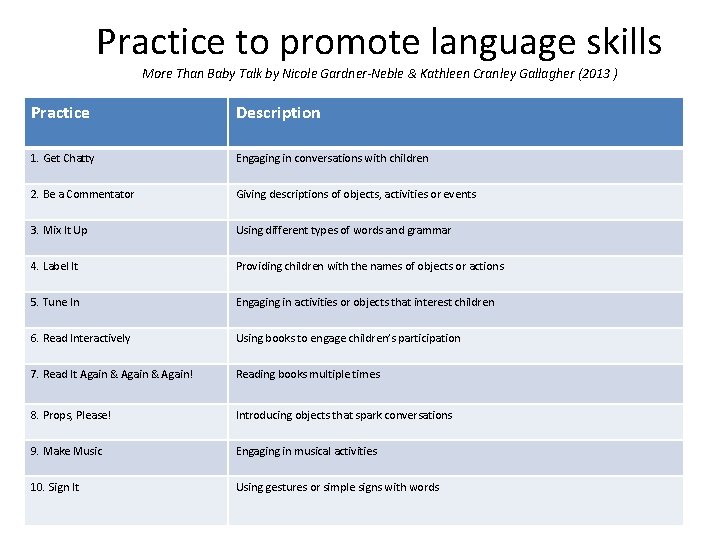

Practice to promote language skills More Than Baby Talk by Nicole Gardner-Neble & Kathleen Cranley Gallagher (2013 ) Practice Description 1. Get Chatty Engaging in conversations with children 2. Be a Commentator Giving descriptions of objects, activities or events 3. Mix It Up Using different types of words and grammar 4. Label It Providing children with the names of objects or actions 5. Tune In Engaging in activities or objects that interest children 6. Read Interactively Using books to engage children’s participation 7. Read It Again & Again! Reading books multiple times 8. Props, Please! Introducing objects that spark conversations 9. Make Music Engaging in musical activities 10. Sign It Using gestures or simple signs with words

Mathematical development The first few years of a child’s life are especially important for mathematics development. Research shows that early mathematical knowledge predicts later reading ability and general education and social progress. (Duncan et al. 2007)

Ages 0– 12 months • Begin to predict the sequence of events (like running water means bath time) Start to understand basic cause and effect (shaking a rattle makes noise) Begin to classify things in simple ways (some toys make noise and some don’t) Start to understand relative size (baby is small, parents are big) • Begin to understand words that describe quantities (more, bigger, enough)

Ages 1– 2 years • Understand that numbers mean “how many” (using fingers to show many years old they are) Begin reciting numbers, but may skip some of them Understand words that compare or measure things (under, behind, faster) • Match basic shapes (triangle to triangle, circle to circle) Explore measurement by filling and emptying containers • Start seeing patterns in daily routines and in things like floor tiles

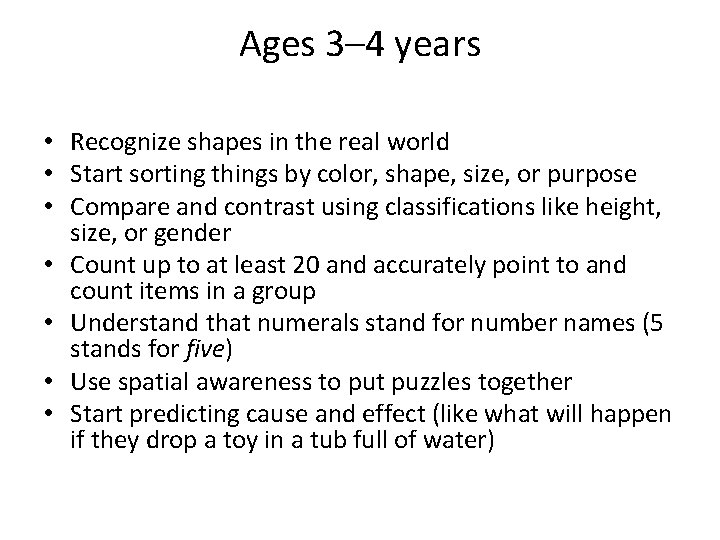

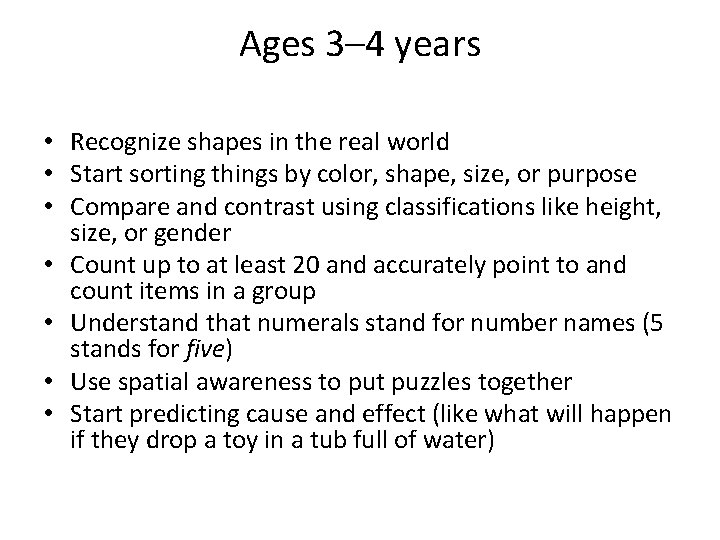

Ages 3– 4 years • Recognize shapes in the real world • Start sorting things by color, shape, size, or purpose • Compare and contrast using classifications like height, size, or gender • Count up to at least 20 and accurately point to and count items in a group • Understand that numerals stand for number names (5 stands for five) • Use spatial awareness to put puzzles together • Start predicting cause and effect (like what will happen if they drop a toy in a tub full of water)

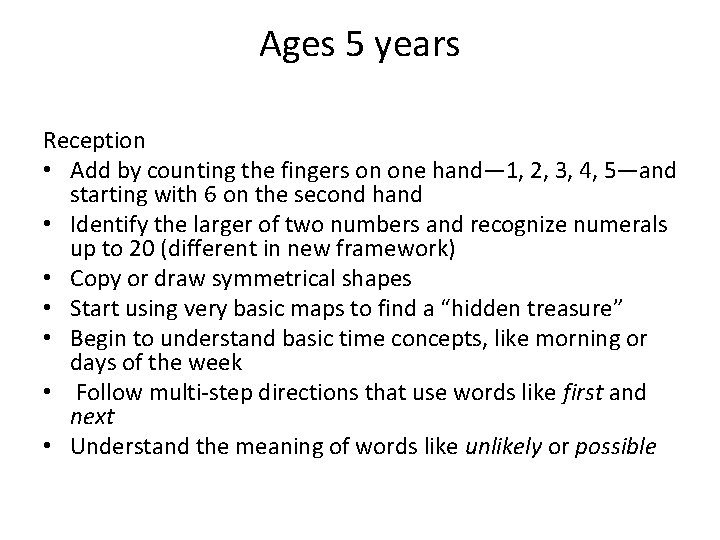

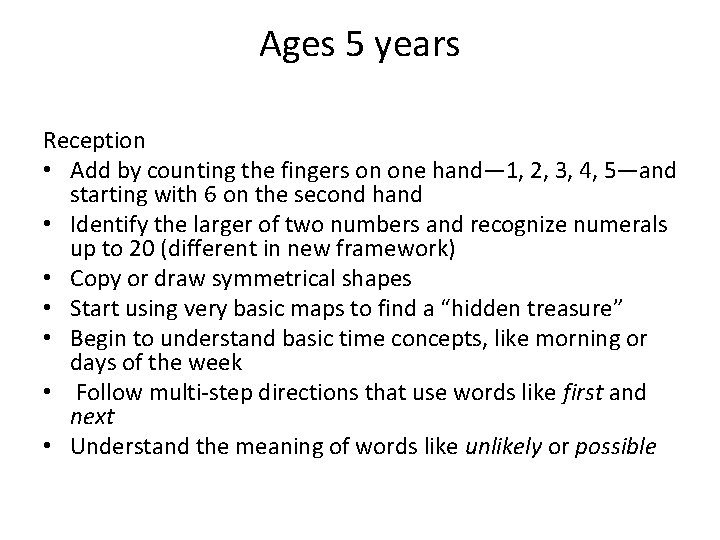

Ages 5 years Reception • Add by counting the fingers on one hand— 1, 2, 3, 4, 5—and starting with 6 on the second hand • Identify the larger of two numbers and recognize numerals up to 20 (different in new framework) • Copy or draw symmetrical shapes • Start using very basic maps to find a “hidden treasure” • Begin to understand basic time concepts, like morning or days of the week • Follow multi-step directions that use words like first and next • Understand the meaning of words like unlikely or possible

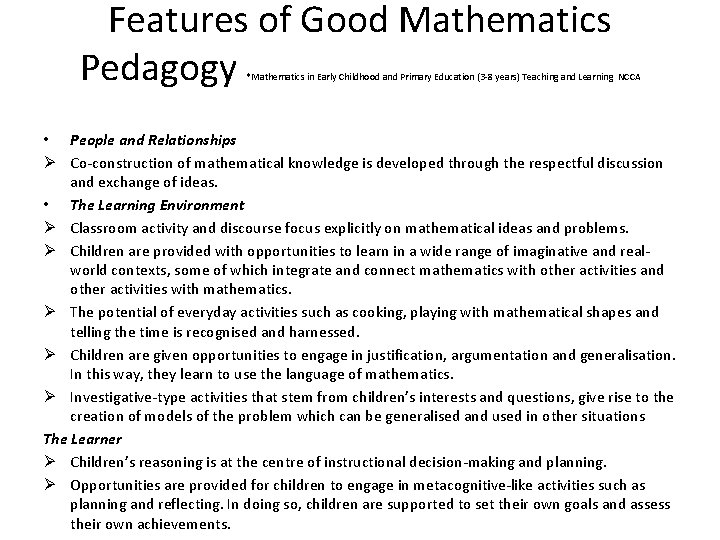

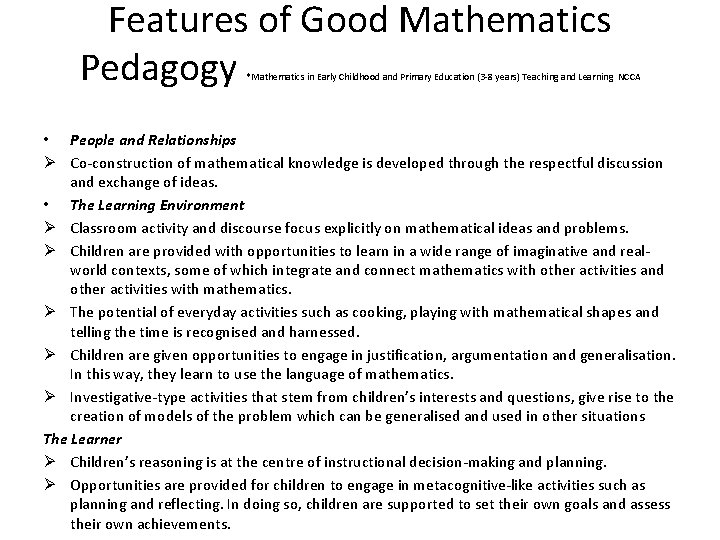

Features of Good Mathematics Pedagogy *Mathematics in Early Childhood and Primary Education (3 -8 years) Teaching and Learning NCCA • People and Relationships Ø Co-construction of mathematical knowledge is developed through the respectful discussion and exchange of ideas. • The Learning Environment Ø Classroom activity and discourse focus explicitly on mathematical ideas and problems. Ø Children are provided with opportunities to learn in a wide range of imaginative and realworld contexts, some of which integrate and connect mathematics with other activities and other activities with mathematics. Ø The potential of everyday activities such as cooking, playing with mathematical shapes and telling the time is recognised and harnessed. Ø Children are given opportunities to engage in justification, argumentation and generalisation. In this way, they learn to use the language of mathematics. Ø Investigative-type activities that stem from children’s interests and questions, give rise to the creation of models of the problem which can be generalised and used in other situations The Learner Ø Children’s reasoning is at the centre of instructional decision-making and planning. Ø Opportunities are provided for children to engage in metacognitive-like activities such as planning and reflecting. In doing so, children are supported to set their own goals and assess their own achievements.

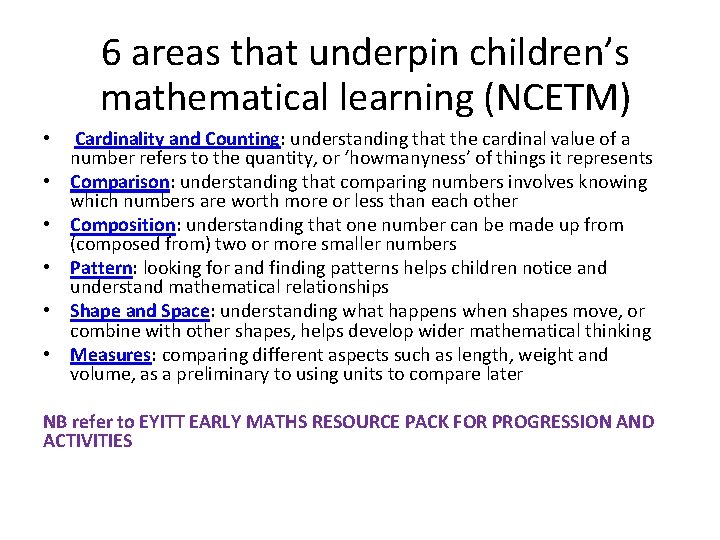

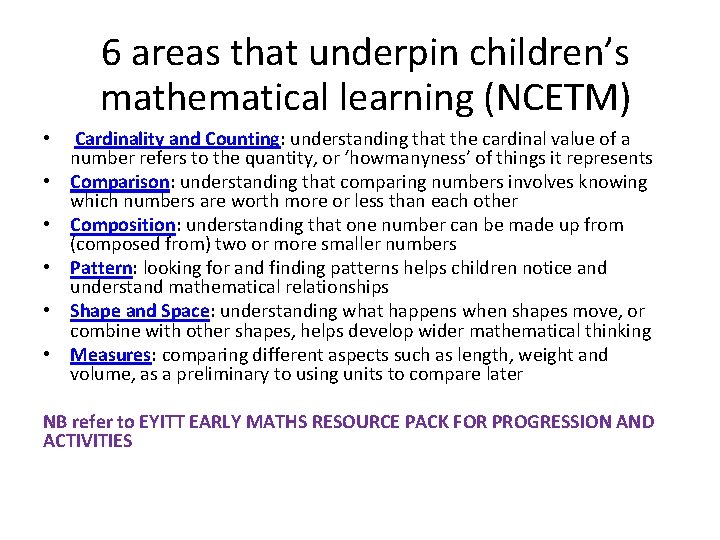

6 areas that underpin children’s mathematical learning (NCETM) • Cardinality and Counting: understanding that the cardinal value of a number refers to the quantity, or ‘howmanyness’ of things it represents • Comparison: understanding that comparing numbers involves knowing which numbers are worth more or less than each other • Composition: understanding that one number can be made up from (composed from) two or more smaller numbers • Pattern: looking for and finding patterns helps children notice and understand mathematical relationships • Shape and Space: understanding what happens when shapes move, or combine with other shapes, helps develop wider mathematical thinking • Measures: comparing different aspects such as length, weight and volume, as a preliminary to using units to compare later NB refer to EYITT EARLY MATHS RESOURCE PACK FOR PROGRESSION AND ACTIVITIES

Transitions and routines • How do you effectively incorporate mathematics into them? • For babies? • For toddlers? • For young children? • What do you need to consider differently for each phase? • What are the commonalities?

‘Real life’ opportunities/scenarios • What ‘real life’ opportunities are there for purposeful mathematical problem-solving? • How can we integrate them into their nursery/school experience?

Maths rich environment Activity: Use your SSTEW sub scale 4, item 12: Supporting children’s concept development and higher order thinking. In your breakout rooms : • Discuss and Identify how specific aspects of provision supports mathematical development. • Share ideas. Would you develop anything?

• Planning themes • In your groups, plan how you are going to develop one of themes from today in your setting: Ø Sustained Shared Thinking Ø Language rich environment (from the audits from last week and theory sessions today) Ø Maths provision (from developmental milestones and SSTEW activity)

To reflect on back at your setting…. . • Share your SSTEW area with your setting mentor / peer Identify one change you could make to this are of practice • Update your setting plan to reflect this

ITERIM TASK • Plan an activity that supports one of the prime areas of learning and development (Communication and language development; Physical development; Personal, social and emotional development) • Be prepared to share this activity with your peers at CPLD Day 3 (effective practice with 0 - 20 month age phase)

Discussion and Q&A • The Change Project

To Finish…. . COMPLETE THE EVALUATION FORM