Expert segment Cognitive Load Theory Presented by Christine

Expert segment: Cognitive Load Theory Presented by Christine Lindstrøm 1 March 2021

Cognitive Load Theory (CLT): Origins • Developed by John Sweller (now Emeritus Professor) from our very own UNSW. • Idea formulated in the late 1980 s, which has grown to a significant and influential body of literature. • Sits in cognitive psychology. • Builds on G. A. Miller’s work from the 1950 s that showed working memory capacity is severely limited. • Usingle-digit numbers, Miller (1956) showed that humans were only able to store 7± 2 individual bits of information. Miller, G. A. (1956). "The magical number seven, plus or minus two: some limits on our capacity for processing information". Psychological Review. 63 (2): 81– 97.

Cognitive Psychology simplified Long term memory Attention Working memory

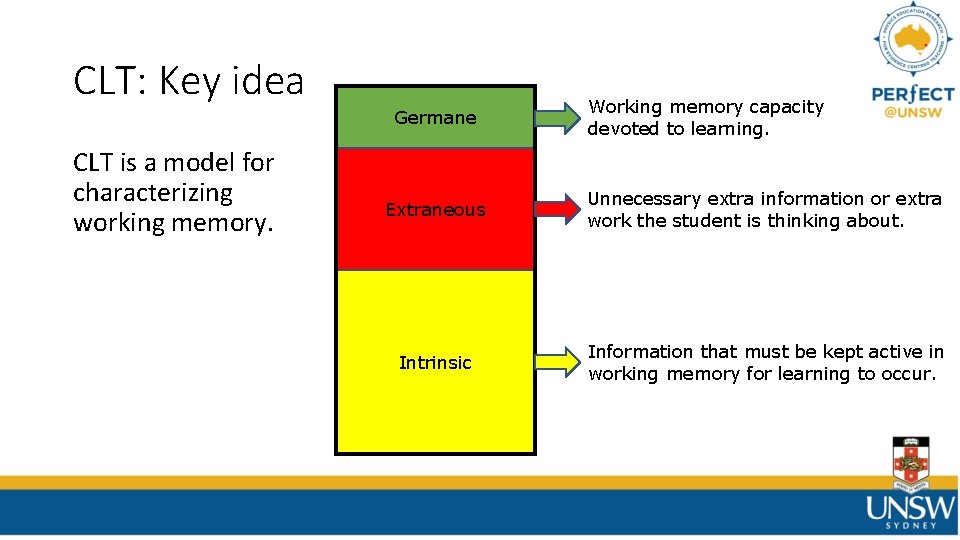

CLT: Key idea CLT is a model for characterizing working memory. Germane Working memory capacity devoted to learning. Extraneous Unnecessary extra information or extra work the student is thinking about. Intrinsic Information that must be kept active in working memory for learning to occur.

Cognitive overload

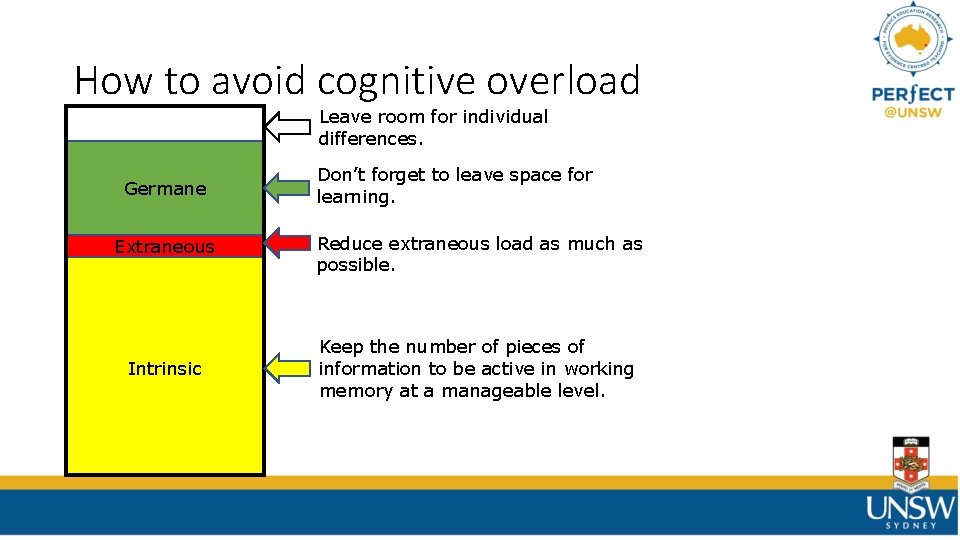

How to avoid cognitive overload Leave room for individual differences. Germane Don’t forget to leave space for learning. Extraneous Reduce extraneous load as much as possible. Intrinsic Keep the number of pieces of information to be active in working memory at a manageable level.

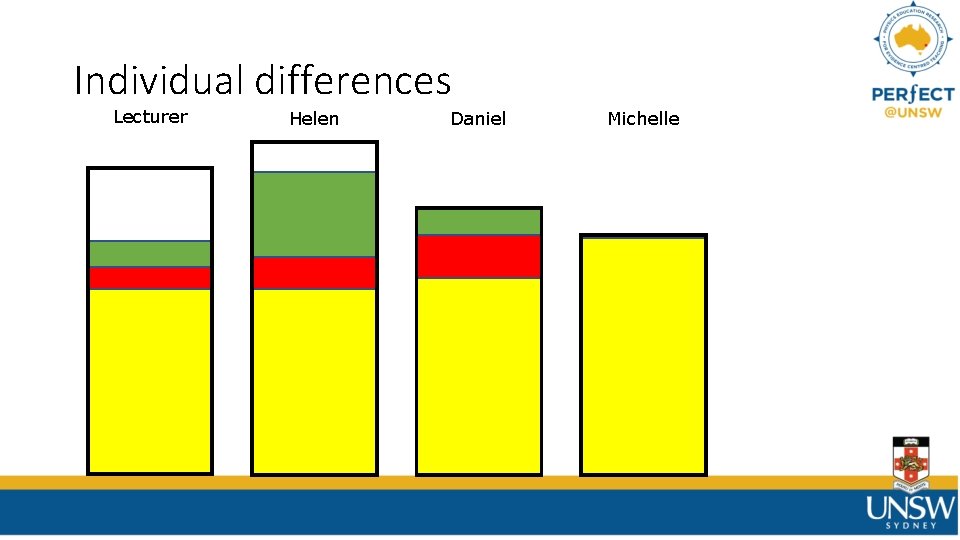

Individual differences Lecturer Helen Daniel Michelle

CLT: Usefulness • "Cognitive load theory has been designed to provide guidelines intended to assist in the presentation of information in a manner that encourages learner activities that optimize intellectual performance” (Sweller et al. , 1998). • The usefulness of CLT is in carefully considering the information students are to process when learning. Sweller, John; van Merrienboer, Jeroen J. G. ; Paas, Fred G. W. C. (1998). "Cognitive Architecture and Instructional Design". Educational Psychology Review. 10(3): 251– 296.

How to evaluate intrinsic load? 7± 2 Student: 3 pieces of information Lecturer: 1 integrated piece (chunk) Chase, William G. ; Simon, Herbert A. (January 1973). "Perception in chess". Cognitive Psychology. 4 (1): 55– 81.

Visualising germane load New information

CLT applications (1/2) Studies in the 1990 s demonstrated several learning effects: • Modality effect: learner performance depends on the presentation mode of studied items (e. g. , auditory vs. visual). • Split-attention effect: the negative impact on learning when attention must be split across modalities (auditory vs. visual), space (in two different places), or time and integrated cognitively by the learner (taking up working memory capacity) instead of being presented in an integrated for. Moreno, R. & Mayer, R. E. (1999). "Cognitive principles of multimedia learning: The role of modality and contiguity". Journal of Educational Psychology. 91 (2): 358– 368. Mousavi, S. Y. , Low, R. & Sweller, J. (1995). "Reducing cognitive load by mixing auditory and visual presentation modes". Journal of Educational Psychology. 87 (2): 319– 334. Chandler, P. & Sweller, J. (1992). "The split-attention effect as a factor in the design of instruction". British Journal of Educational Psychology. 62 (2): 233– 246.

CLT applications (2/2) Studies in the 1990 s demonstrated several learning effects: • Worked example effect: improves learning by reducing cognitive load during skill acquisition by reducing intrinsic cognitive load in the early stages. • Expertise reversal effect: refers to the reversal of the effectiveness of instructional techniques on learners with differing levels of prior knowledge, such that instructional design methods need to be adjusted as learners acquire more knowledge in a specific domain. Cooper, G. & Sweller, J. (1987). "Effects of schema acquisition and rule automation on mathematical problem-solving transfer". J. Ed. Psych. 79 (4): 347– 362. Sweller, J. & Cooper, G. A. (2009). "The Use of Worked Examples as a Substitute for Problem Solving in Learning Algebra". Cognition and Instruction. 2 (1): 59– 89. Kalyuga, S. , Ayres, P. , Chandler, P. & Sweller, J. (2003). ”The Expertise Reversal Effect. ” Educational Psychologist. 38 (1): 23– 31.

- Slides: 12