Event Based Systems Time and synchronization Dependability Dr

Event Based Systems Time and synchronization Dependability Dr. Emanuel Onica Faculty of Computer Science, Alexandru Ioan Cuza University of Iaşi

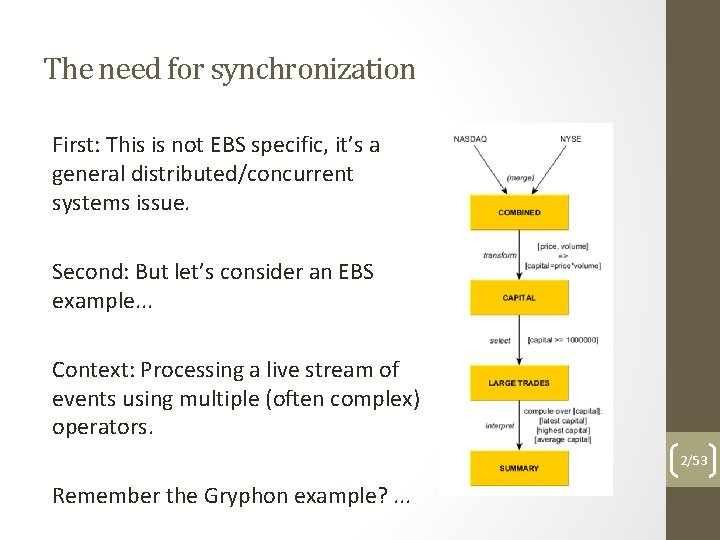

The need for synchronization First: This is not EBS specific, it’s a general distributed/concurrent systems issue. Second: But let’s consider an EBS example. . . Context: Processing a live stream of events using multiple (often complex) operators. 2/53 Remember the Gryphon example? . . .

The need for synchronization The need for correlation: - e. g. , agreggate data for last minute of transactions on both NASDAQ and NYSE (sync on different data sources) The need for performance: - e. g. , parallelize transform and/or select operator sequence by adding multiple instances, needing a centralized output for interpret (sync on similar parallel computation results) 3/53

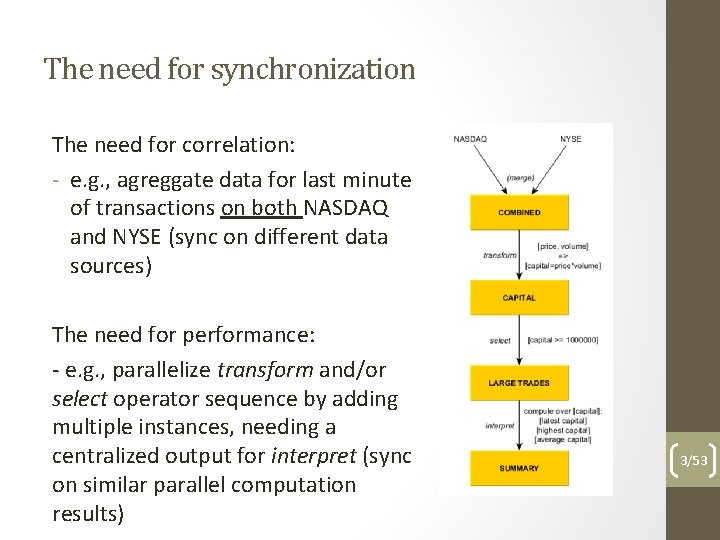

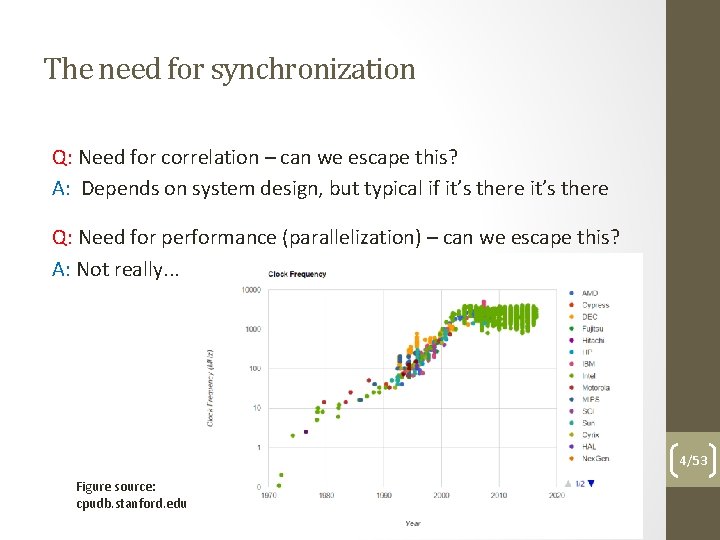

The need for synchronization Q: Need for correlation – can we escape this? A: Depends on system design, but typical if it’s there Q: Need for performance (parallelization) – can we escape this? A: Not really. . . 4/53 Figure source: cpudb. stanford. edu

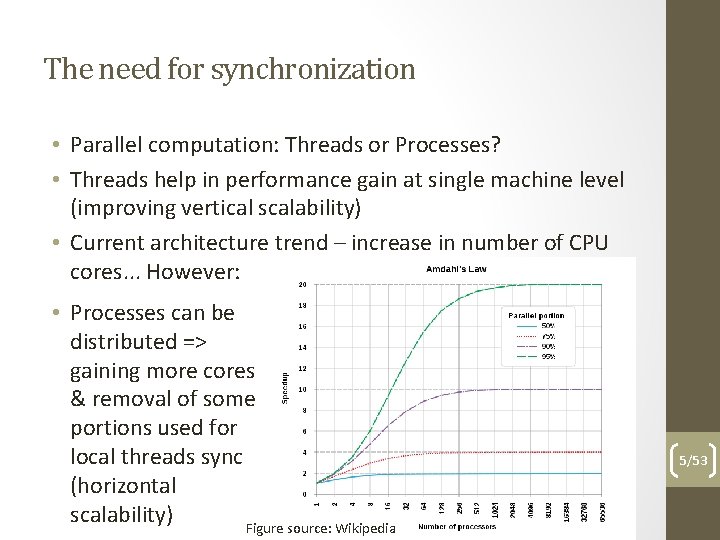

The need for synchronization • Parallel computation: Threads or Processes? • Threads help in performance gain at single machine level (improving vertical scalability) • Current architecture trend – increase in number of CPU cores. . . However: • Processes can be distributed => gaining more cores & removal of some portions used for local threads sync (horizontal scalability) Figure source: Wikipedia 5/53

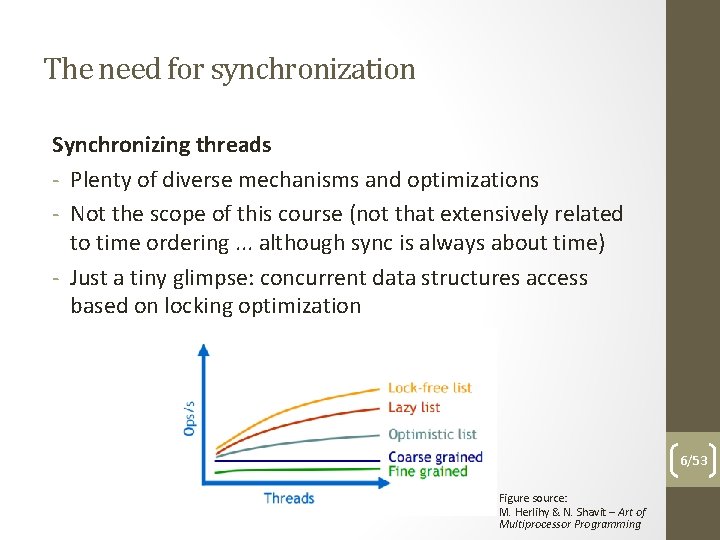

The need for synchronization Synchronizing threads - Plenty of diverse mechanisms and optimizations - Not the scope of this course (not that extensively related to time ordering. . . although sync is always about time) - Just a tiny glimpse: concurrent data structures access based on locking optimization 6/53 Figure source: M. Herlihy & N. Shavit – Art of Multiprocessor Programming

The need for synchronization Synchronizing processes (distributed nodes) Q: Why is time effectively important? A: Need for correlation/causality – we need node A to do something before/after/while node B does something • External synchronization • Processes reference a clock external to the system to coordinate their actions (e. g. , adjust their time based on UTC) • Internal synchronization • Processes use a „clock” internal to the system to coordinate their actions (e. g. , stamp messages for ordering based on some algorithm) 7/53

The need for synchronization • External synchronization • (Extreme) example: process A has to do something at start time = 3: 15: 22: 001 AM which takes duration t = 9 ms; process B must wait duration t = 9 ms for process A and execute at start time = 3: 15: 22: 010 AM • Problem: A drift (difference in clock frequency) typically exists per process, which can increase skew (difference in clock time) • Solution: synchronize process clocks periodically to minimize skew (e. g. , NTP) • Problem: There will always still be an error rate due to messaging latency (e. g. , in NTP is bound by the message round trip-time) • Solution: use internal synchronization (when we don’t care about any fixed external clock but just about proper ordering. . . which is almost always) 8/53

Lamport timestamps • Defined by Leslie Lamport in 1978. • Basic idea: • define a logical happens-before predicate on pair of events • label events with timestamps that respect the order imposed by the predicate • Basic idea explained: • A → B : means that event A happened before event B (causality, e. g. : A – sending of a message by node 1, B – message receival at node 2) • If A → B and B → C then A → C (tranzitivity) • If A → B then timestamp(A) < timestamp(B) • Not all events can be ordered in pairs (e. g. , concurrent events occuring in different processes without causal relationship) 9/53

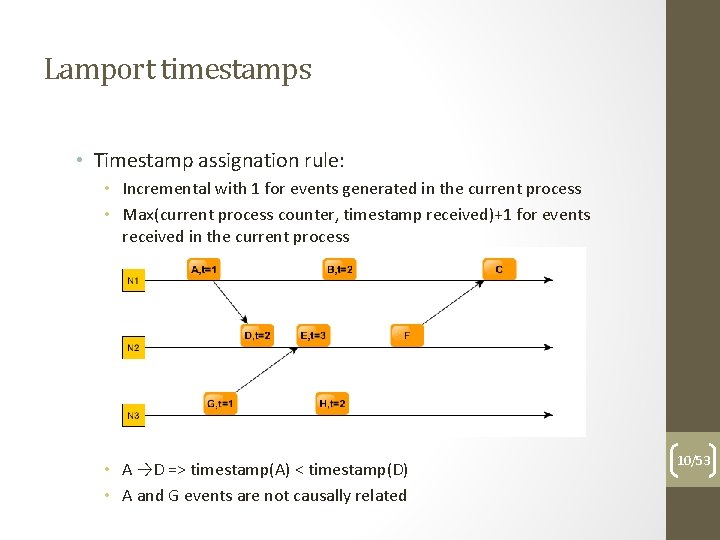

Lamport timestamps • Timestamp assignation rule: • Incremental with 1 for events generated in the current process • Max(current process counter, timestamp received)+1 for events received in the current process • A →D => timestamp(A) < timestamp(D) • A and G events are not causally related 10/53

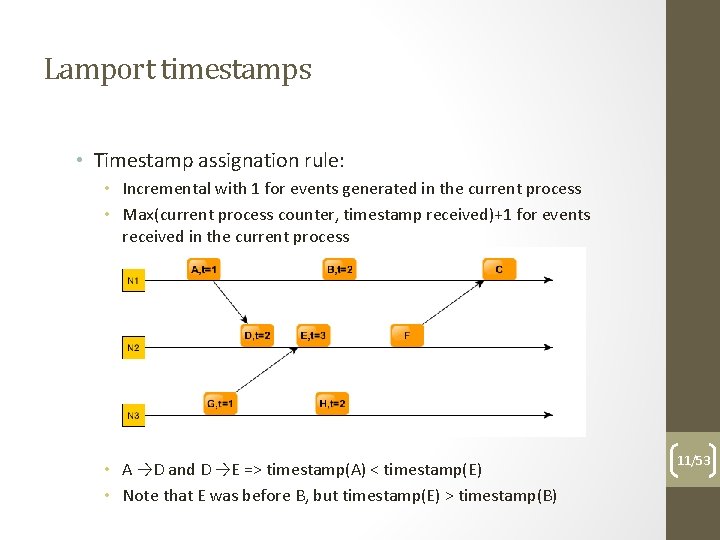

Lamport timestamps • Timestamp assignation rule: • Incremental with 1 for events generated in the current process • Max(current process counter, timestamp received)+1 for events received in the current process • A →D and D →E => timestamp(A) < timestamp(E) • Note that E was before B, but timestamp(E) > timestamp(B) 11/53

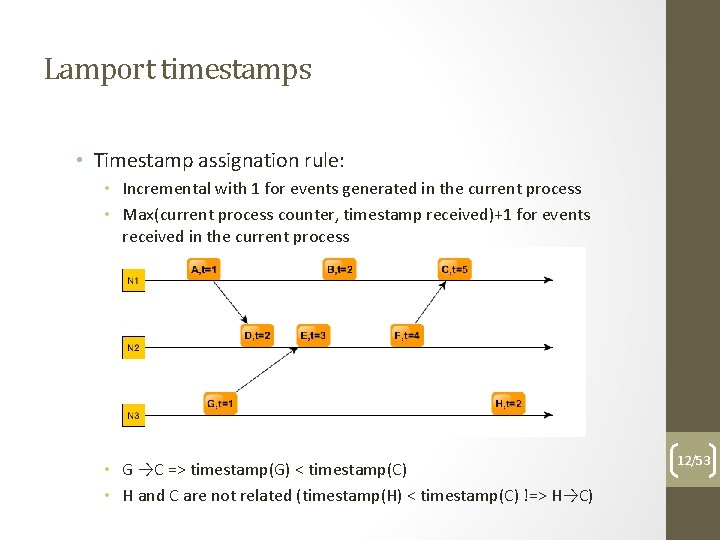

Lamport timestamps • Timestamp assignation rule: • Incremental with 1 for events generated in the current process • Max(current process counter, timestamp received)+1 for events received in the current process • G →C => timestamp(G) < timestamp(C) • H and C are not related (timestamp(H) < timestamp(C) !=> H→C) 12/53

Lamport timestamps • Summary: • The order is partial – timestamps not ordered for causally unrelated events • The relationship is not bijective: if A→B then timestamp(A) < timestamp(B), but if timestamp(A) < timestamp(B), not necessarily A→B • So, if timestamp(A) < timestamp(B) we don’t really know the relation between A and B … • Can we do better than this? 13/53

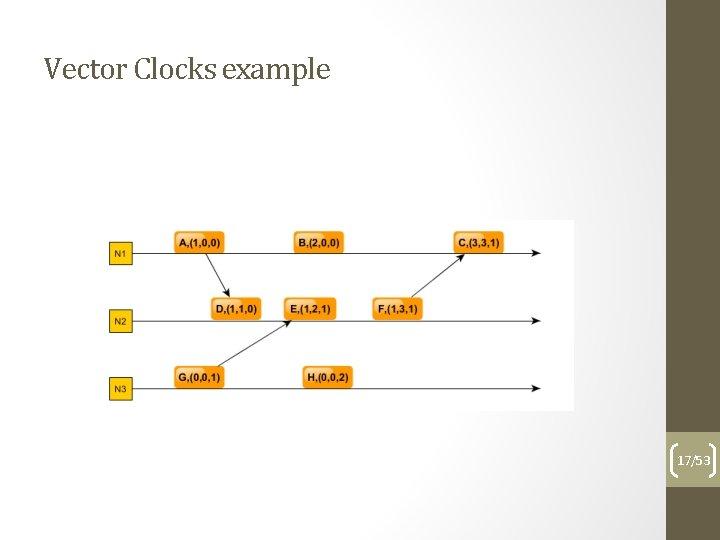

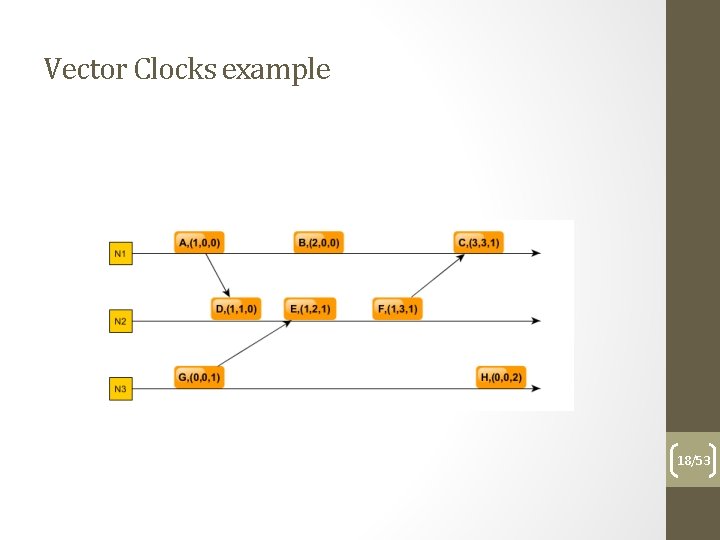

Vector clocks Using multiple time tags per process helps in determining the exact happens-before relation as resulting from tags: - each process will use a vector of N values where N = number of processes, initialized with 0 - the i-th element of the vector clock is the clock of the i-th process - the vector is send along the messages - if a process sends a message, increments just its own clock in the vector - If a process receives a message increments its own clock in the local vector and sets the rest of the clocks to the max(clock value in local vector, clock value in received vector) 14/53

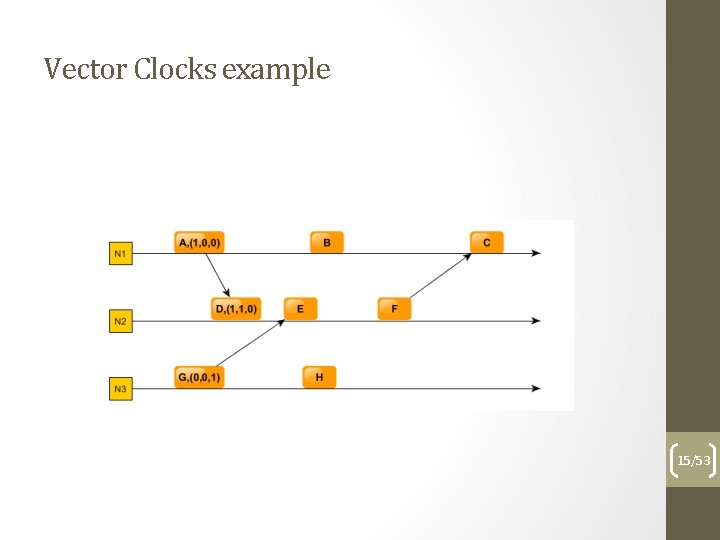

Vector Clocks example 15/53

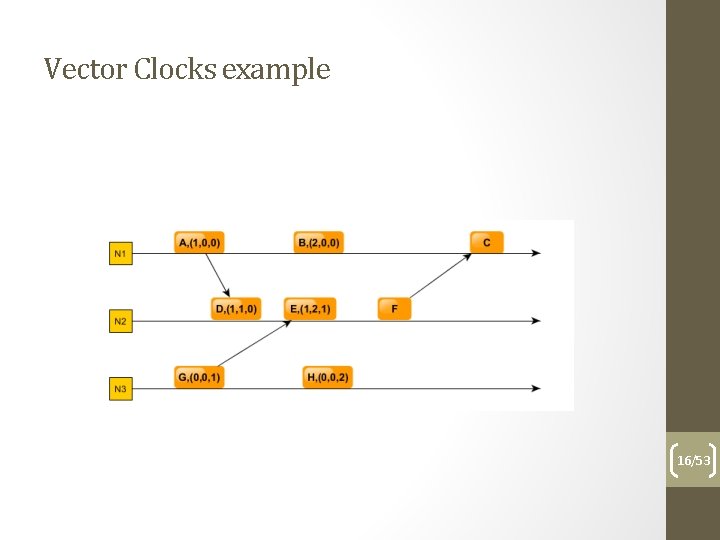

Vector Clocks example 16/53

Vector Clocks example 17/53

Vector Clocks example 18/53

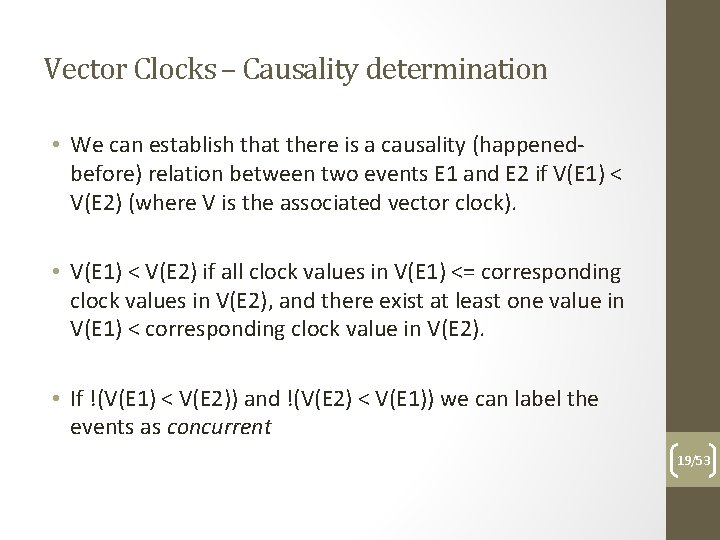

Vector Clocks – Causality determination • We can establish that there is a causality (happenedbefore) relation between two events E 1 and E 2 if V(E 1) < V(E 2) (where V is the associated vector clock). • V(E 1) < V(E 2) if all clock values in V(E 1) <= corresponding clock values in V(E 2), and there exist at least one value in V(E 1) < corresponding clock value in V(E 2). • If !(V(E 1) < V(E 2)) and !(V(E 2) < V(E 1)) we can label the events as concurrent 19/53

Event Based Systems Dependability Credits for (most of) event based systems dependability slides content to Dr. André Martin (TU Dresden, Germany) Lecture taught at FII during 2016 -2018 academic years as part of EBSIS project Summary: • • Intro on EBS Dependability Passive Replication Brief Look on Active Replication Adaptive Fault Tolerance Typical context: stream of events processed via operators, potentially deployed on multiple nodes (like in a Storm topology) (note: some notions apply in general to distributed systems) 20/53

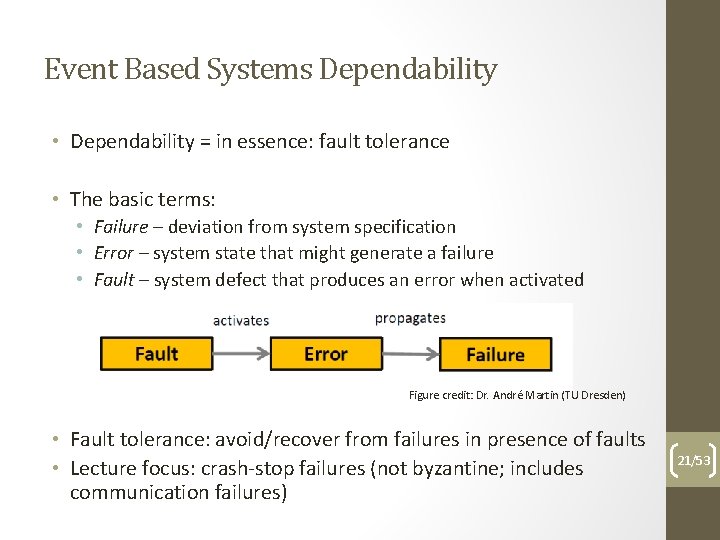

Event Based Systems Dependability • Dependability = in essence: fault tolerance • The basic terms: • Failure – deviation from system specification • Error – system state that might generate a failure • Fault – system defect that produces an error when activated Figure credit: Dr. André Martin (TU Dresden) • Fault tolerance: avoid/recover from failures in presence of faults • Lecture focus: crash-stop failures (not byzantine; includes communication failures) 21/53

Event Based Systems Dependability • Failure detection: broad area of research • Most used practical approaches: heart beats & Zookeeper • Failure recovery levels: • Precise recovery • Gap recovery • Rollback recovery (classification according to: „High-Availability Algorithms for Distributed Stream Processing”, J. Hwang et al. , ICDE 2005) 22/53

Event Based Systems Dependability • Precise recovery: no event is lost or processed twice • e 1, e 2, e 3| e 4, e 5, e 6 • Gap recovery: some events may be lost but system reaches a state consistent with the non-faulty case • e 1, e 2, e 3| e 4, e 5, e 6 • Rollback recovery: events may be processed twice, may lead to different event flow and system state outcome may differ • repeating: e 1, e 2, e 3| e 2, e 3, e 4 (system state recovered) • converging: e 1, e 2, e 3| e 2’, e 3’, e 4 (system state recovered) • diverging: e 1, e 2, e 3| e 2’, e 3’, e 4’ (different system state) 23/53

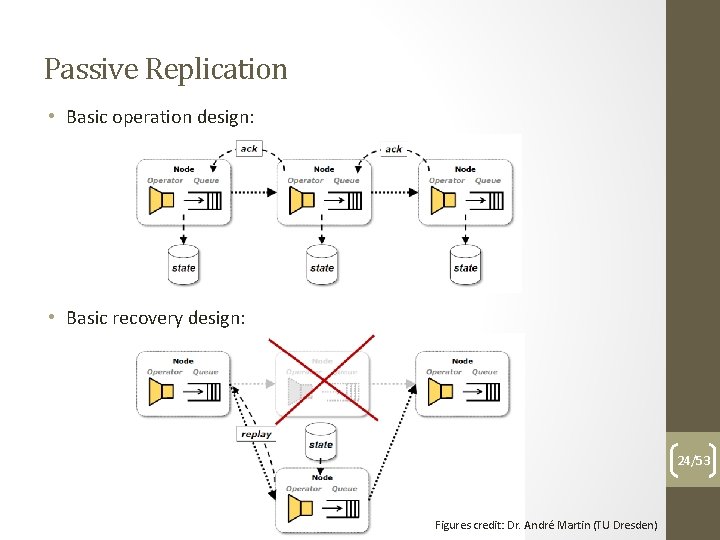

Passive Replication • Basic operation design: • Basic recovery design: 24/53 Figures credit: Dr. André Martin (TU Dresden)

Passive Replication • The basic principles: • State preservation via checkpointing • Event preservation via logging • Normal operation phase: • Periodical marking of system state checkpoints • Log in-flight events to memory or disk • Recovery phase: • Reload system state from latest checkpoint • Replay logged events since reloaded checkpoint state 25/53

Passive Replication Various design choices: • When to checkpoint? • Coordinated vs. non-coordinated checkpointing • What to checkpoint? • Operator state, timestamps, input or output queue, etc. • How to checkpoint? • Serialization vs. simple data structures • When to log events and when to prune these? • Depends on operator nature and needs for state recovery • How to log events? • In memory or on disk 26/53

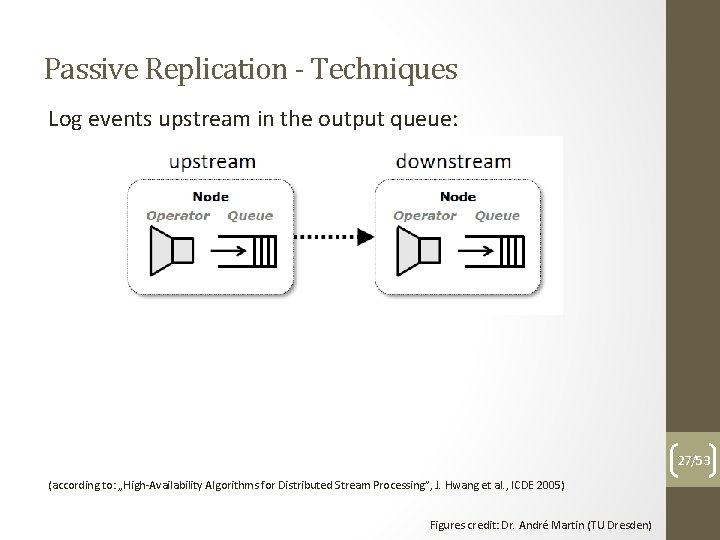

Passive Replication - Techniques Log events upstream in the output queue: 27/53 (according to: „High-Availability Algorithms for Distributed Stream Processing”, J. Hwang et al. , ICDE 2005) Figures credit: Dr. André Martin (TU Dresden)

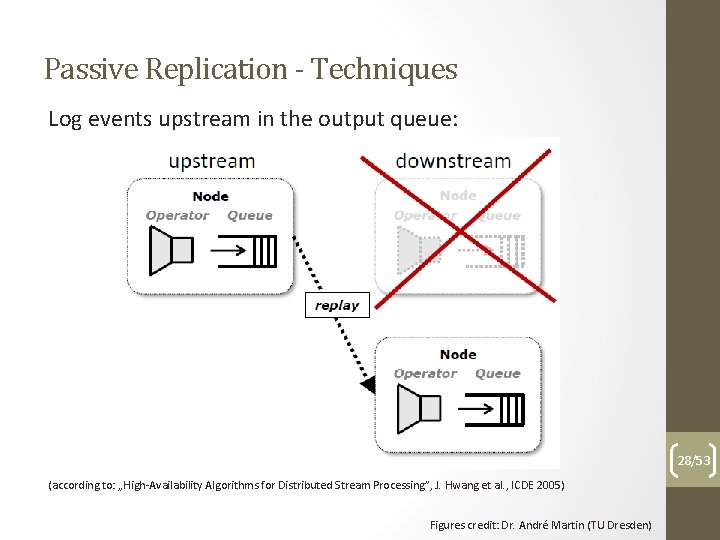

Passive Replication - Techniques Log events upstream in the output queue: 28/53 (according to: „High-Availability Algorithms for Distributed Stream Processing”, J. Hwang et al. , ICDE 2005) Figures credit: Dr. André Martin (TU Dresden)

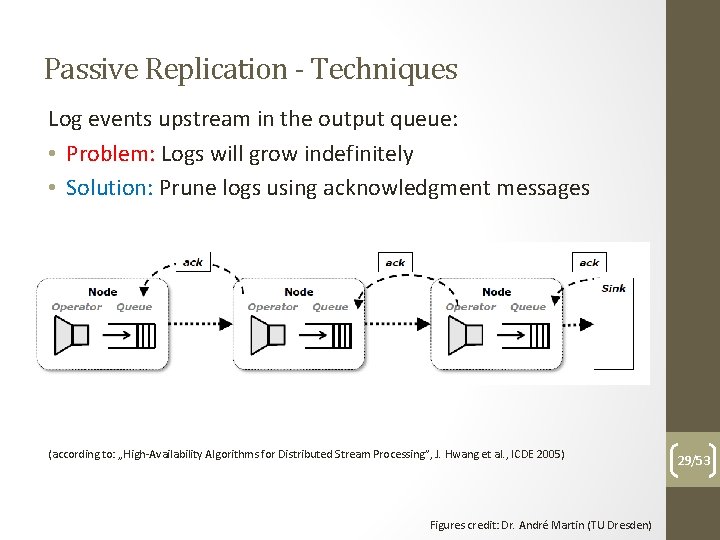

Passive Replication - Techniques Log events upstream in the output queue: • Problem: Logs will grow indefinitely • Solution: Prune logs using acknowledgment messages (according to: „High-Availability Algorithms for Distributed Stream Processing”, J. Hwang et al. , ICDE 2005) Figures credit: Dr. André Martin (TU Dresden) 29/53

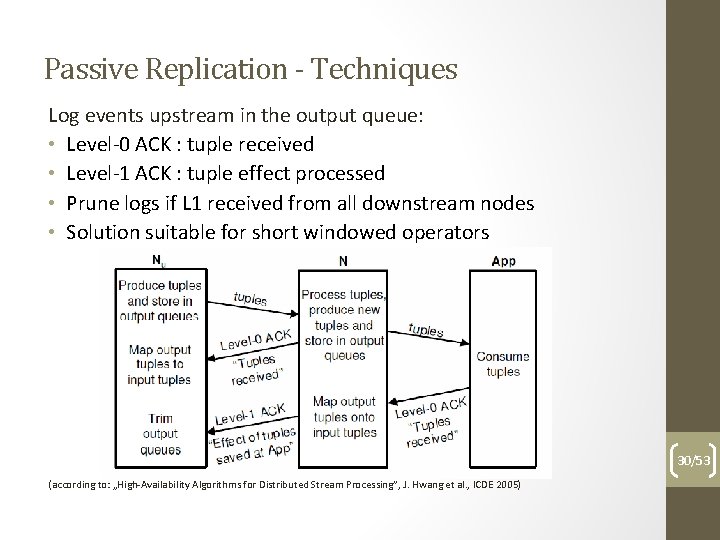

Passive Replication - Techniques Log events upstream in the output queue: • Level-0 ACK : tuple received • Level-1 ACK : tuple effect processed • Prune logs if L 1 received from all downstream nodes • Solution suitable for short windowed operators 30/53 (according to: „High-Availability Algorithms for Distributed Stream Processing”, J. Hwang et al. , ICDE 2005)

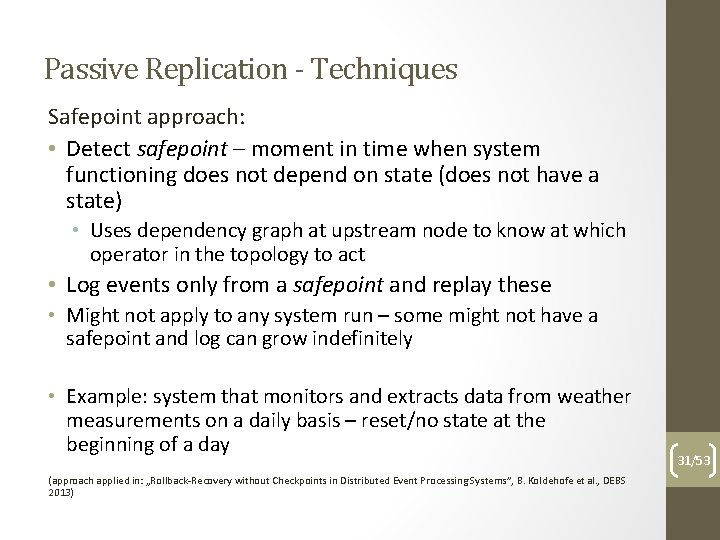

Passive Replication - Techniques Safepoint approach: • Detect safepoint – moment in time when system functioning does not depend on state (does not have a state) • Uses dependency graph at upstream node to know at which operator in the topology to act • Log events only from a safepoint and replay these • Might not apply to any system run – some might not have a safepoint and log can grow indefinitely • Example: system that monitors and extracts data from weather measurements on a daily basis – reset/no state at the beginning of a day (approach applied in: „Rollback-Recovery without Checkpoints in Distributed Event Processing Systems”, B. Koldehofe et al. , DEBS 2013) 31/53

Passive Replication - Techniques Sweeping checkpointing: • Guarantees precise recovery if operators are deterministic • Checkpoints operator state and events in output queue • Operators functioning must be stopped during serialization • Recovery time is state size dependent (details in: “An empirical study of high availability in stream processing systems”, Z. Zhang et al. , Middleware 2009) 32/53

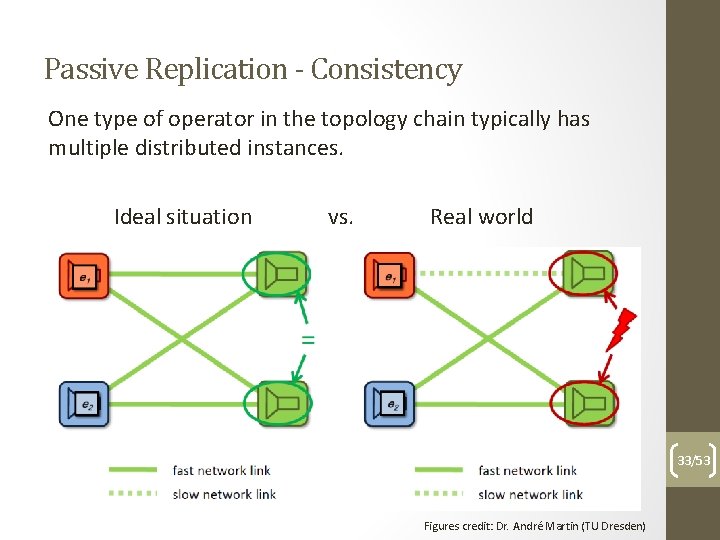

Passive Replication - Consistency One type of operator in the topology chain typically has multiple distributed instances. Ideal situation vs. Real world 33/53 Figures credit: Dr. André Martin (TU Dresden)

Passive Replication - Consistency Need to ensure that all events are replayed in the same order to each operator instance. Worst case scenario: non-determinism – the events are not ordered by design and their arrival order at an operator instance can determine different states. Must log events to disk and perform coordinated checkpointing to ensure state consistency. Most costly situation. 34/53

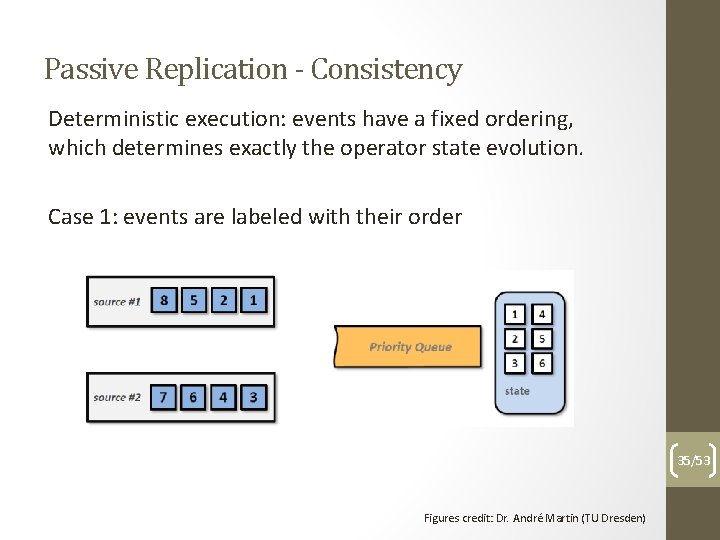

Passive Replication - Consistency Deterministic execution: events have a fixed ordering, which determines exactly the operator state evolution. Case 1: events are labeled with their order 35/53 Figures credit: Dr. André Martin (TU Dresden)

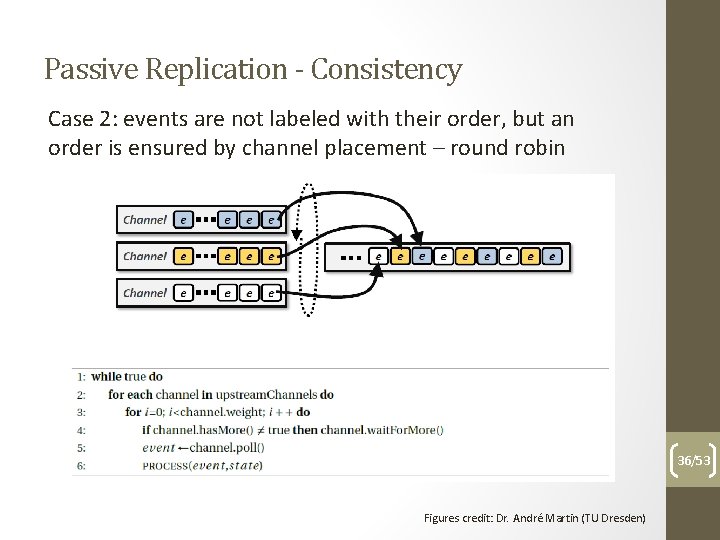

Passive Replication - Consistency Case 2: events are not labeled with their order, but an order is ensured by channel placement – round robin 36/53 Figures credit: Dr. André Martin (TU Dresden)

Passive Replication - Consistency In each case: • Events are blocked and must be ordered • Latency increases and implies runtime overhead Some operators might permit partial unordered processing of events like jumping-window or commutative – e. g. , aggregation, join, etc. Optimization idea: epoch based processing 37/53

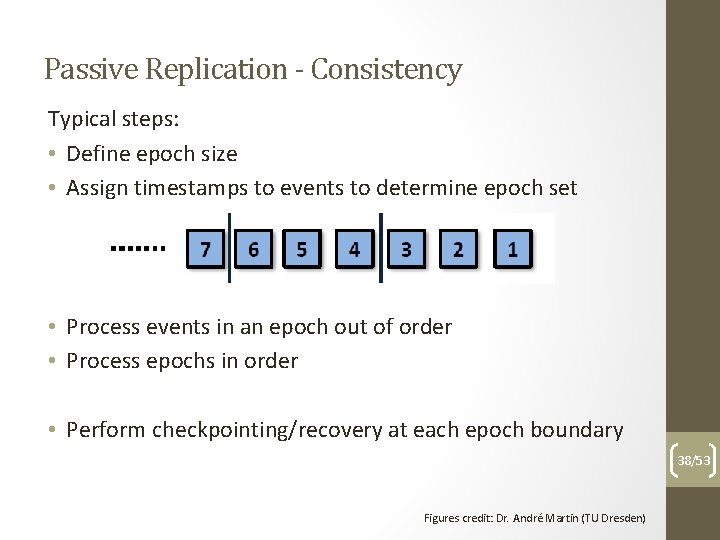

Passive Replication - Consistency Typical steps: • Define epoch size • Assign timestamps to events to determine epoch set • Process events in an epoch out of order • Process epochs in order • Perform checkpointing/recovery at each epoch boundary 38/53 Figures credit: Dr. André Martin (TU Dresden)

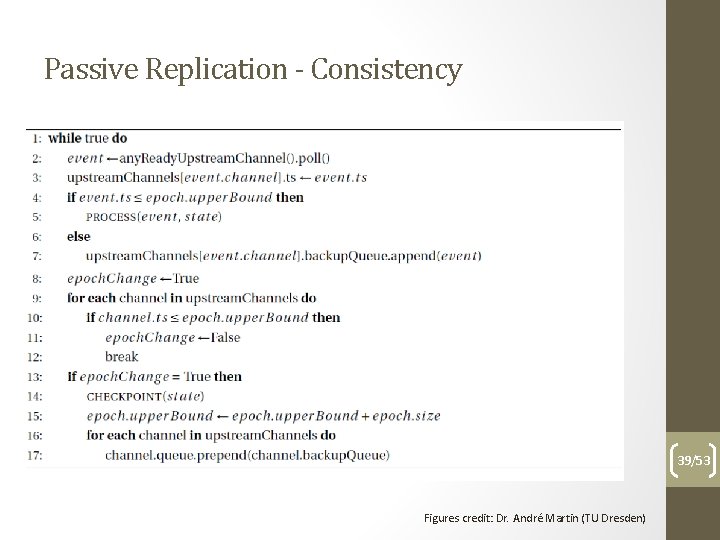

Passive Replication - Consistency 39/53 Figures credit: Dr. André Martin (TU Dresden)

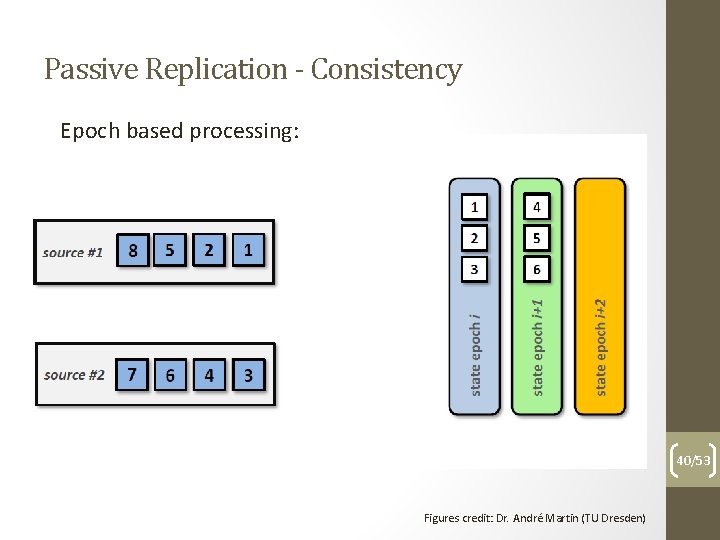

Passive Replication - Consistency Epoch based processing: 40/53 Figures credit: Dr. André Martin (TU Dresden)

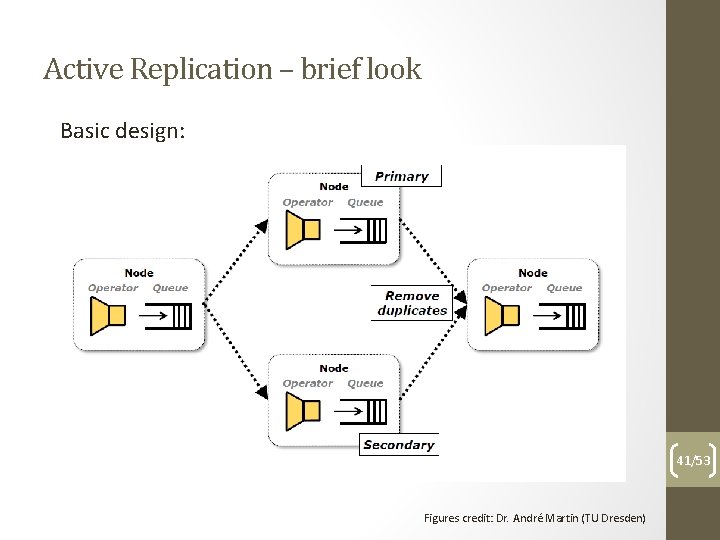

Active Replication – brief look Basic design: 41/53 Figures credit: Dr. André Martin (TU Dresden)

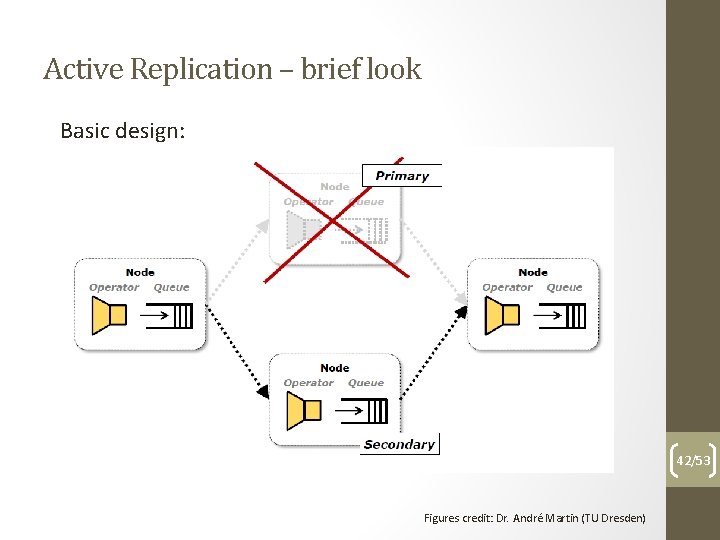

Active Replication – brief look Basic design: 42/53 Figures credit: Dr. André Martin (TU Dresden)

Active Replication – brief look Basic principles: • Normal operation • Replicate events • Deterministically process events • Filter out duplicates • Recovery operation • Re-deploy new replica after fail 43/53

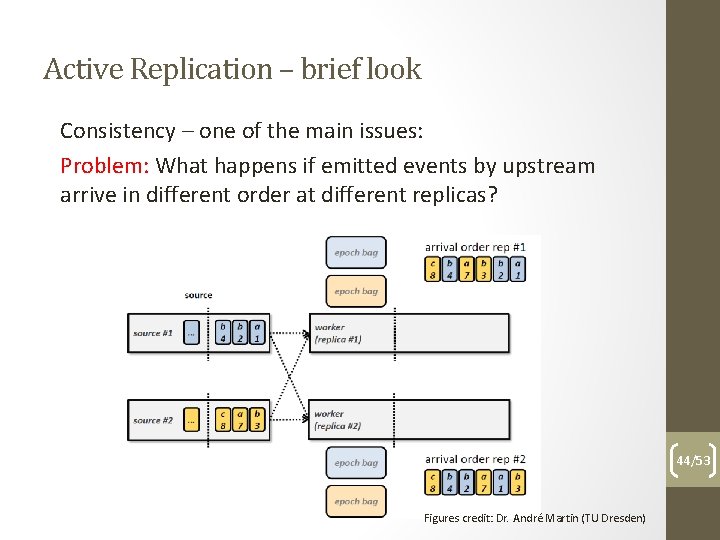

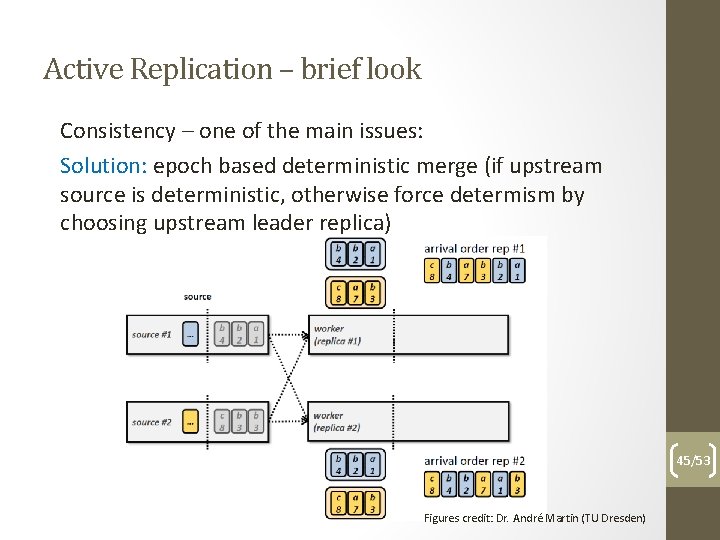

Active Replication – brief look Consistency – one of the main issues: Problem: What happens if emitted events by upstream arrive in different order at different replicas? 44/53 Figures credit: Dr. André Martin (TU Dresden)

Active Replication – brief look Consistency – one of the main issues: Solution: epoch based deterministic merge (if upstream source is deterministic, otherwise force determism by choosing upstream leader replica) 45/53 Figures credit: Dr. André Martin (TU Dresden)

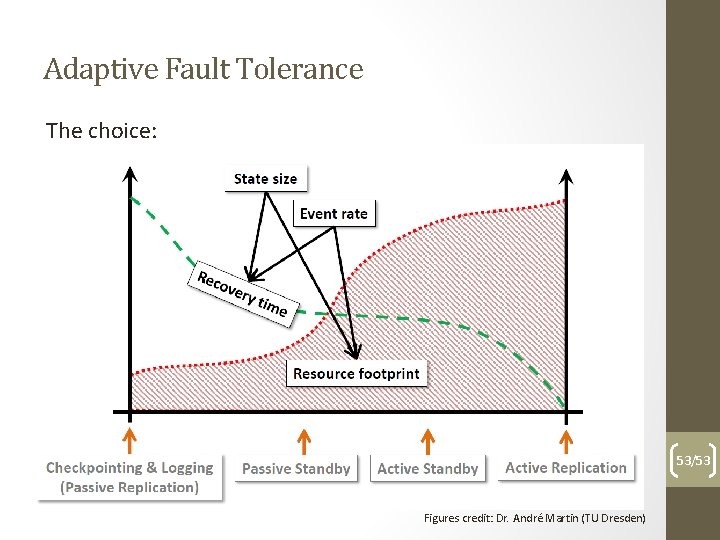

Adaptive Fault Tolerance Main idea: adaptively change used solution according to your needs 46/53

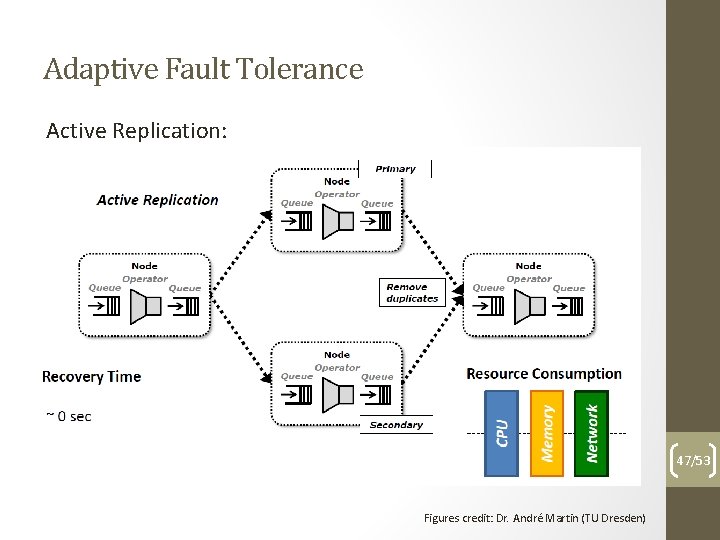

Adaptive Fault Tolerance Active Replication: 47/53 Figures credit: Dr. André Martin (TU Dresden)

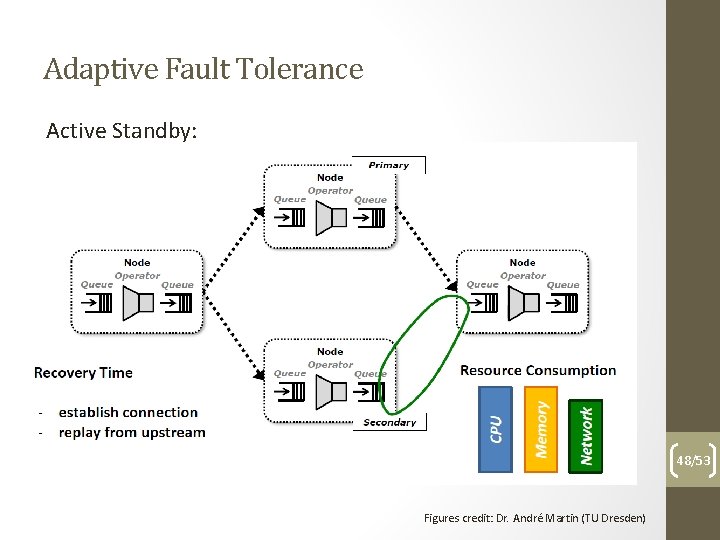

Adaptive Fault Tolerance Active Standby: 48/53 Figures credit: Dr. André Martin (TU Dresden)

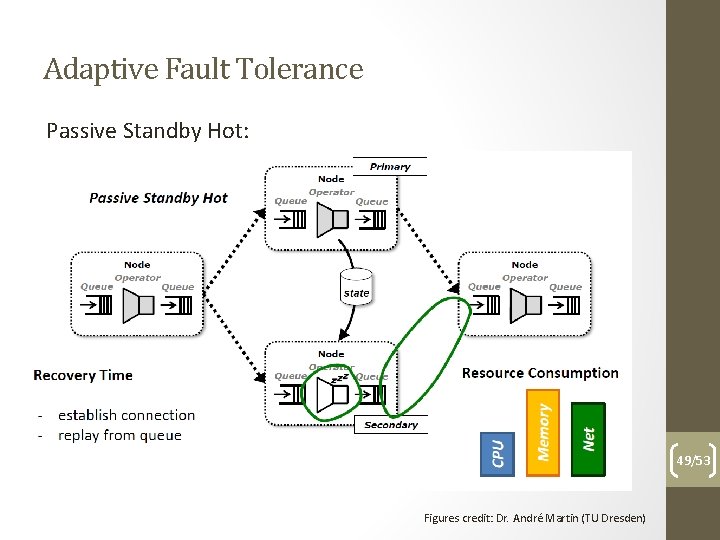

Adaptive Fault Tolerance Passive Standby Hot: 49/53 Figures credit: Dr. André Martin (TU Dresden)

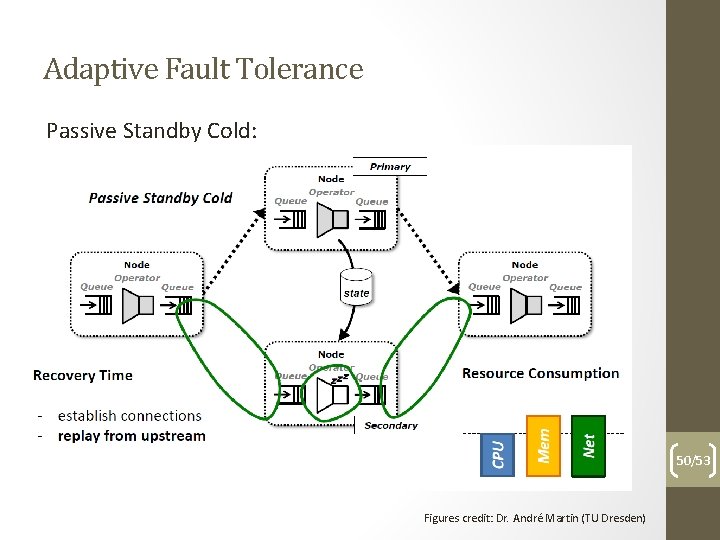

Adaptive Fault Tolerance Passive Standby Cold: 50/53 Figures credit: Dr. André Martin (TU Dresden)

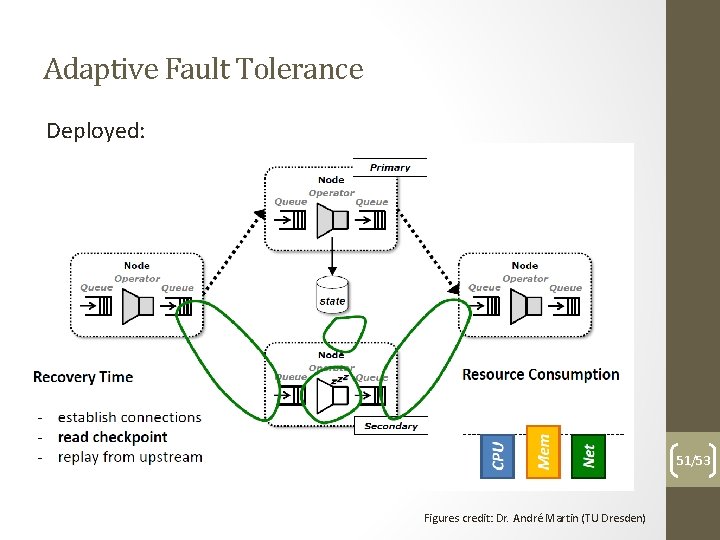

Adaptive Fault Tolerance Deployed: 51/53 Figures credit: Dr. André Martin (TU Dresden)

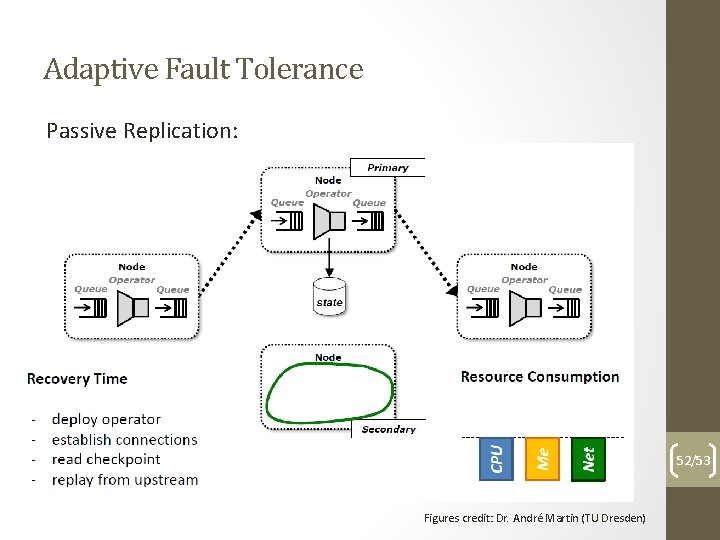

Adaptive Fault Tolerance Passive Replication: 52/53 Figures credit: Dr. André Martin (TU Dresden)

Adaptive Fault Tolerance The choice: 53/53 Figures credit: Dr. André Martin (TU Dresden)

- Slides: 53