Event Based Systems Gossip protocols intro CAP theorem

Event Based Systems Gossip protocols intro CAP theorem and Zookeeper Dr. Emanuel Onica Faculty of Computer Science, Alexandru Ioan Cuza University of Iaşi

Contents 1. A short intro on gossip 2. CAP theorem 3. BASE vs ACID 4. Zookeeper 2/35

Gossip Data Dissemination Main context: Send data to a group. „Classic” approach: IP Multicast (using UDP - unreliable) Other solutions: • Scalable Reliable Multicast – S. Floyd et al. 1997 – uses a form of NACKs: repair requests, sent by receiving nodes that detect a loss • Reliable Multicast Transport Protocol – S. Paul et al. 1997 – uses selective ACKs: sent to a particular set of receivers organized in hierarchy • Pragmatic General Multicast – RFC 3208 experimental – uses a hop-byhop NACK notification when data loss is detected, and extra confirmation for NACKs Confirmation = Overhead. . . Can we do without it? Multicast group = Size limit. . . Can we break it? 3/35

Gossip Data Dissemination Some history: • First proposed in the context of computer science in: Epidemic algorithms for replicated database maintenance. – Demers et al. 1987 • Problem context: • Xerox had databases replicated on multiple nodes; • Local updates must be replicated on all other database copies; • E-mailing updates (initial solution) creates an overburden at the source site and doesn’t scale. 4/35

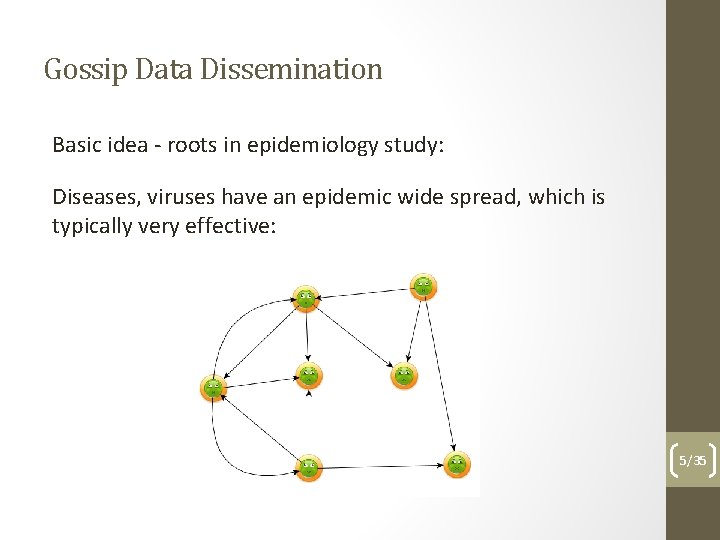

Gossip Data Dissemination Basic idea - roots in epidemiology study: Diseases, viruses have an epidemic wide spread, which is typically very effective: 5/35

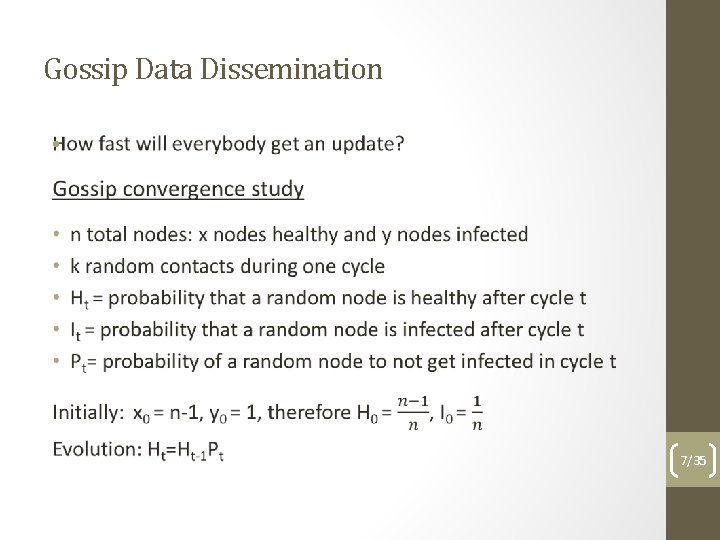

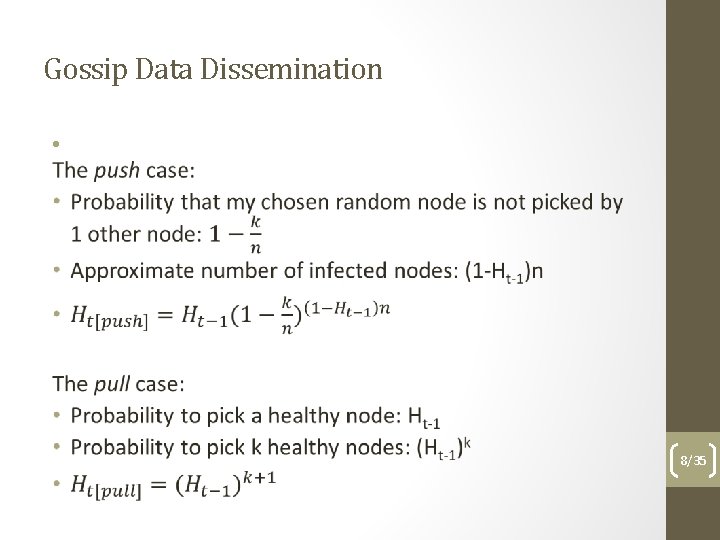

Gossip Data Dissemination Let’s apply the idea in a distributed system. Simplest epidemic spreading – anti-entropy: • two states: healthy (not updated) and infected (updated) • spread happens in timed cycles • two ways of dissemination – at each cycle: • Push: each infected node picks k random nodes to send updates; nodes become infected if they were not • Pull: each non-infected node asks k random nodes for updates; the node becomes infected if it was not 6/35

Gossip Data Dissemination • 7/35

Gossip Data Dissemination • 8/35

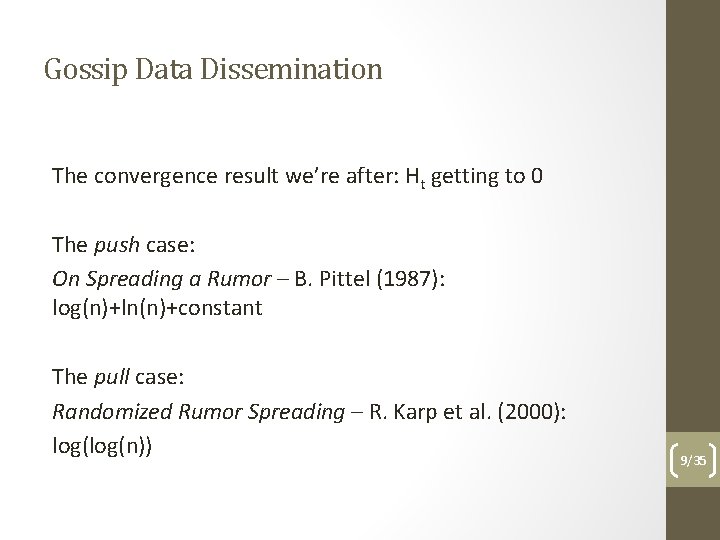

Gossip Data Dissemination The convergence result we’re after: Ht getting to 0 The push case: On Spreading a Rumor – B. Pittel (1987): log(n)+ln(n)+constant The pull case: Randomized Rumor Spreading – R. Karp et al. (2000): log(n)) 9/35

Gossip Data Dissemination Has been observed that disseminating up to ½ nodes takes O(log n) time no matter which method is used. Dissemination can be assimilated with a tree topology fan-out which is logarithmic. However, for the last half of the nodes, pull converges much faster. Therefore a hybrid push-pull approach might be better since push can be more lightweight on communication (no reply overhead). Latest results: Optimal epidemic dissemination (H. Mercier et al. , 2017) show Θ(ln n) rounds bounds for either pull or push-pull 10/35

The CAP Theorem First formulated by Eric Brewer as a conjecture (PODC 2000). Formal proof by Seth Gilbert and Nancy Lynch (2002). It is impossible for a distributed computer system to simultaneously provide all three of the following guarantees: • Consistency (all nodes see the same data at the same time) • Availability (all requests are answered with success or failure within a similar timely manner) • Partition tolerance (system continues to work despite arbitrary partitioning due to network fails) 11/35

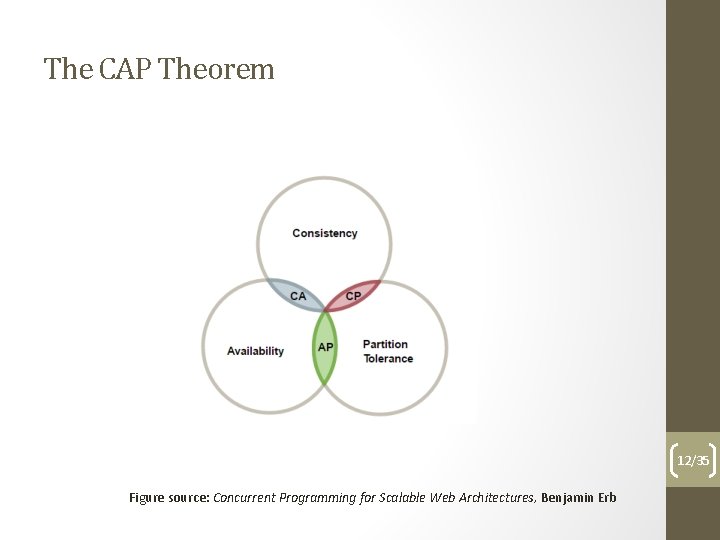

The CAP Theorem 12/35 Figure source: Concurrent Programming for Scalable Web Architectures, Benjamin Erb

The CAP Theorem – the requirements Consistency – why we need it? • Distributed services are used by multiple (up to millions users) • Concurrent reads and writes take place in the distributed systems • We need an unitary view across all sessions and across all data replicas Example: An online shop stores stock info on a distributed storage system. When an user buys a product, the stock info must be updated on every storage replica and be visible to all users across all sessions. 13/35

The CAP Theorem – the requirements Availability – why we need it? • Reads and writes should be completed in a timely reliable fashion, for offering the desired level of Qo. S • Often Service Level Agreements (SLAs) are set in commercial environments to establish desirable parameters of functionality that should be mandatorily be provided • ½ second delay per page load results in 20% drop in traffic and revenue (Google, Web 2. 0 Conference, 2006) • Amazon tests by simulating artificial delays resulted in 6 M dollars per each ms (2009) 14/35

The CAP Theorem – the requirements Partition-tolerance – why we need it? • Multiple data centers used by the same distributed service can be partitioned due to various failures: • • Power outages DNS timeouts Cable failures and others. . . • Failures, or more generally faults in distributed systems are rather the norm than the exception • Let’s say a rack server in a data center has a one downtime in 3 years • Try to figure out how often the data center fails on average if it has 100 servers 15/35

BASE vs ACID – the traditional guarantee set in RDBMS • Atomicity – a transaction either succeds with the change of the database, or fails with a rollback • Consistency – there is no invalid state in a sequence of states caused by transactions • Isolation – each transaction is isolated from the rest, preventing conflicts between concurrent transactions • Durability – each transaction commit is persistent over failures Doesn’t work for distributed storage systems – no coverage for partition tolerance (and this is mandatory) 16/35

BASE vs ACID BASE – Basically Available Soft-state Eventual consistency • Basically Available – ensures the availability requirement in the CAP theorem • Soft-state – there is no strong consistency provided, and the state of the system might be stale at certain times • Eventual consistency – eventually the state of the distributed system converges to a consistent view 17/35

BASE vs ACID BASE model is mostly used in distributed key-value stores, where availability is typically favored over consistency (No. SQL): • Apache Cassandra (originally used by Facebook) • Dynamo DB (Amazon) • Voldemort (Linked. In) There are exceptions: • HBase (inspired from Google’s Big Table) – favors consistency over availability 18/35

Zoo. Keeper – Distributed Coordination Ground idea: • Distributed systems world is like a Zoo, and beasts should be kept on a leash • Multiple instances of distributed applications (the same or different apps) often require synchronizing for proper interaction • Zoo. Keeper is a coordination service where: • The apps coordinated are distributed • The service itself is also distributed Article: Zoo. Keeper: Wait-free coordination for Internetscale systems (P. Hunt et al. – USENIX 2010) 19/35

Zoo. Keeper – Distributed Coordination What do we mean by apps requiring synchronization? Various stuff (it’s a Zoo. . . ): • Detecting group membership validity • Leader election protocols • Mutual exclusive access on shared resources • and others. . . What do we mean by Zoo. Keeper providing coordination? • Zoo. Keeper service does not offer complex server side primitives as above for synchronization • Zoo. Keeper service offers a coordination kernel, exposing an API that can be used by clients to implement what primitives they require 20/35

Zoo. Keeper – Guarantees The Zoo. Keeper coordination kernel provides several guarantees: 1. It is wait-free Let’s stop a bit. . . What does this mean (in general)? • lock-freedom – at least one system component makes progress (system wide throughput is guaranteed, but some components can starve) • wait-freedom – all system components make progress (no individual starvation) 2. It guarantees FIFO ordering for all client operations 3. It guarantees linearizable writes 21/35

Zoo. Keeper – Guarantees (Linearizability) Let’s stop a bit. . . What does linearizability mean (in general)? • An operation has typically an invocation and a response phase – looking at it atomically the invocation and response are indivisible, but in reality is not exactly like this. . . • Property of a linearizable operations execution means that: • Invocation of operations and responses to them can be reordered without change of the system behavior equivalent to a sequence of atomic execution of operations (a sequential history) • The sequential history obtained is semantically correct • If an operation response completes in the original order before another operation starts, it will still complete before in the reordering 22/35

Zoo. Keeper – Guarantees (Linearizability) Example (threads): T 1. lock(); T 2. lock(); T 1. fail; T 2. ok; Let’s reorder. . . a) T 1. lock(); T 1. fail; T 2. lock(); T 2. ok; • it is sequential. . . • . . . but not semantically correct b) T 2. lock(); T 2. ok; T 1. lock(); T 1. fail; • it is sequential. . . • . . . and semantically correct We have b) => the original history is linearizable. Back to ZK, recap: the coordination kernel ensures that application write operations history are linearizable (not the reads). 23/35

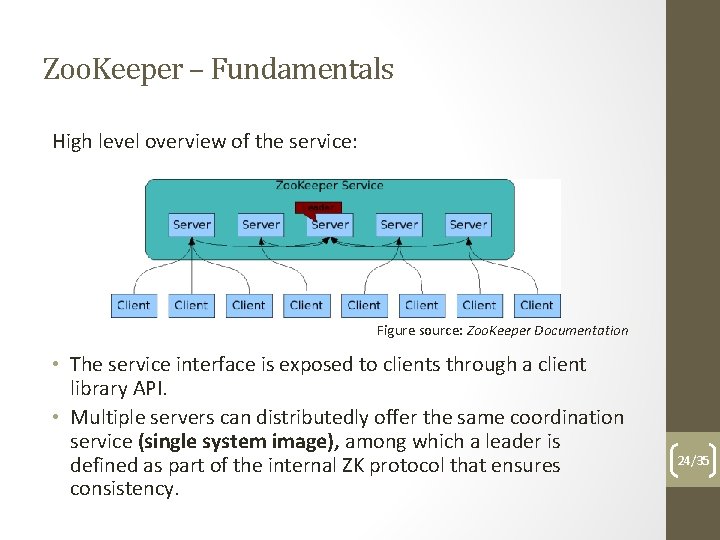

Zoo. Keeper – Fundamentals High level overview of the service: Figure source: Zoo. Keeper Documentation • The service interface is exposed to clients through a client library API. • Multiple servers can distributedly offer the same coordination service (single system image), among which a leader is defined as part of the internal ZK protocol that ensures consistency. 24/35

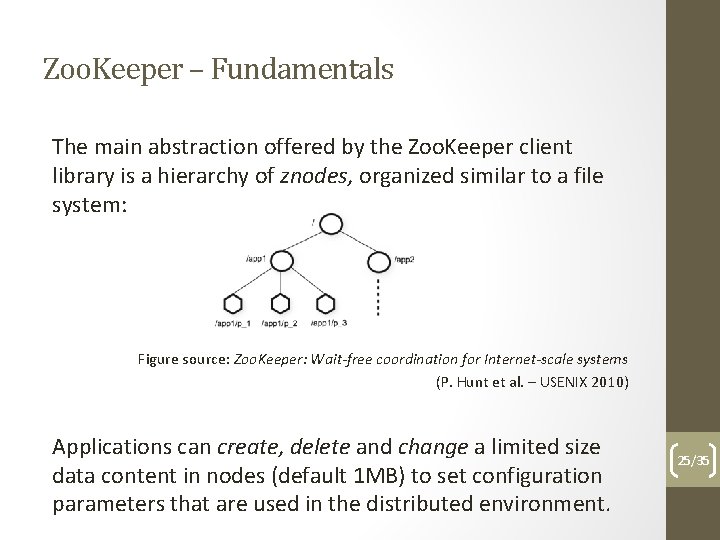

Zoo. Keeper – Fundamentals The main abstraction offered by the Zoo. Keeper client library is a hierarchy of znodes, organized similar to a file system: Figure source: Zoo. Keeper: Wait-free coordination for Internet-scale systems (P. Hunt et al. – USENIX 2010) Applications can create, delete and change a limited size data content in nodes (default 1 MB) to set configuration parameters that are used in the distributed environment. 25/35

Zoo. Keeper – Fundamentals Two types of nodes: • Regular – created and deleted explicitly by apps • Ephemeral – deletion can be performed automatically when session during which creation occured terminates Nodes can be created with the same base name, but having a sequential flag set, for which the ZK service appends an monotonically increasing number. What’s this good for? • same client application (same code), that creates a node to store configuration (e. g. , a pub/sub broker) • run multiple times in distributed fashion • obviously we don’t want to overwrite an existing config node • maybe we also need to organize a queue of nodes based on order • other applications (various algorithms) 26/35

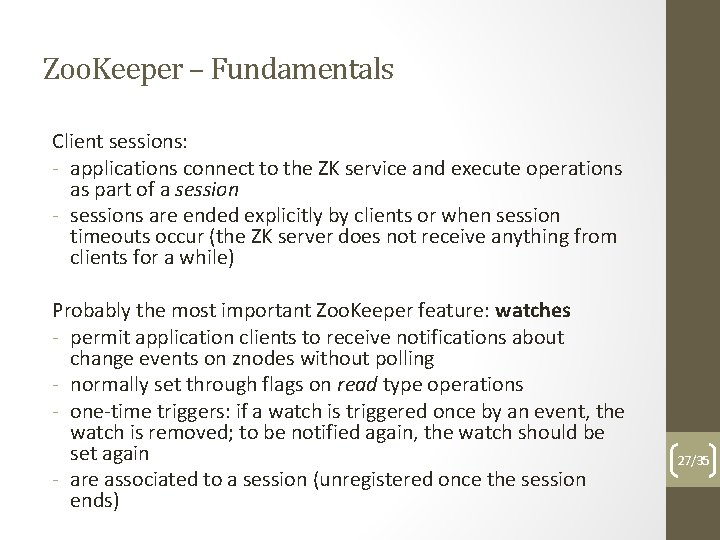

Zoo. Keeper – Fundamentals Client sessions: - applications connect to the ZK service and execute operations as part of a session - sessions are ended explicitly by clients or when session timeouts occur (the ZK server does not receive anything from clients for a while) Probably the most important Zoo. Keeper feature: watches - permit application clients to receive notifications about change events on znodes without polling - normally set through flags on read type operations - one-time triggers: if a watch is triggered once by an event, the watch is removed; to be notified again, the watch should be set again - are associated to a session (unregistered once the session ends) 27/35

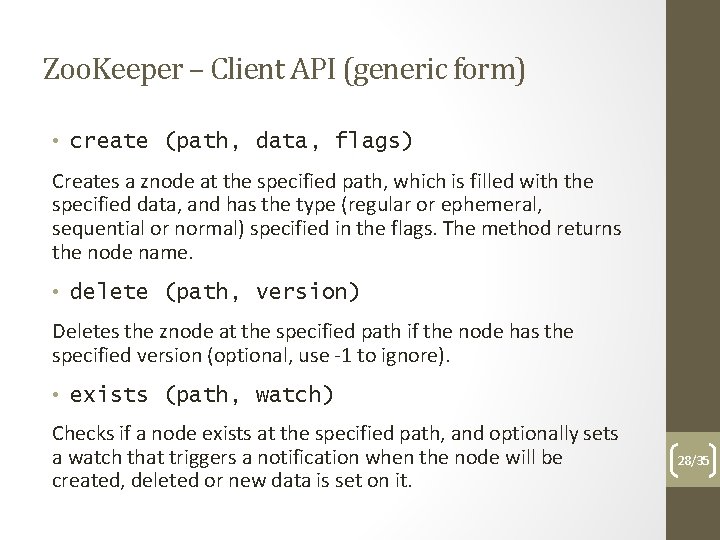

Zoo. Keeper – Client API (generic form) • create (path, data, flags) Creates a znode at the specified path, which is filled with the specified data, and has the type (regular or ephemeral, sequential or normal) specified in the flags. The method returns the node name. • delete (path, version) Deletes the znode at the specified path if the node has the specified version (optional, use -1 to ignore). • exists (path, watch) Checks if a node exists at the specified path, and optionally sets a watch that triggers a notification when the node will be created, deleted or new data is set on it. 28/35

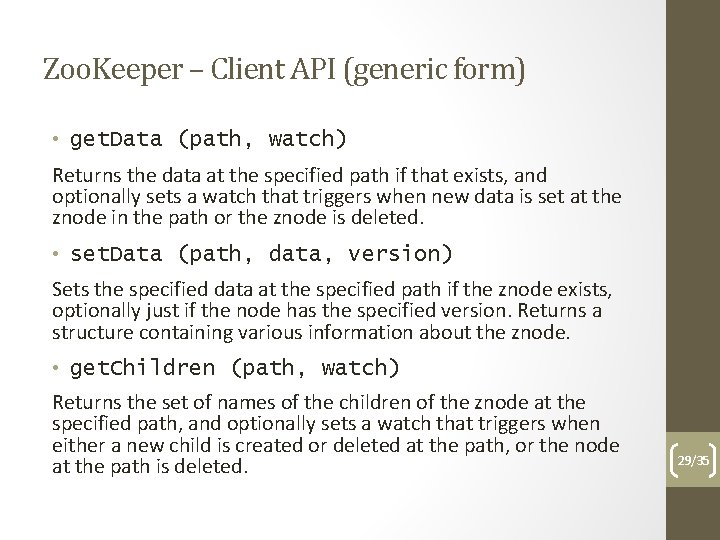

Zoo. Keeper – Client API (generic form) • get. Data (path, watch) Returns the data at the specified path if that exists, and optionally sets a watch that triggers when new data is set at the znode in the path or the znode is deleted. • set. Data (path, data, version) Sets the specified data at the specified path if the znode exists, optionally just if the node has the specified version. Returns a structure containing various information about the znode. • get. Children (path, watch) Returns the set of names of the children of the znode at the specified path, and optionally sets a watch that triggers when either a new child is created or deleted at the path, or the node at the path is deleted. 29/35

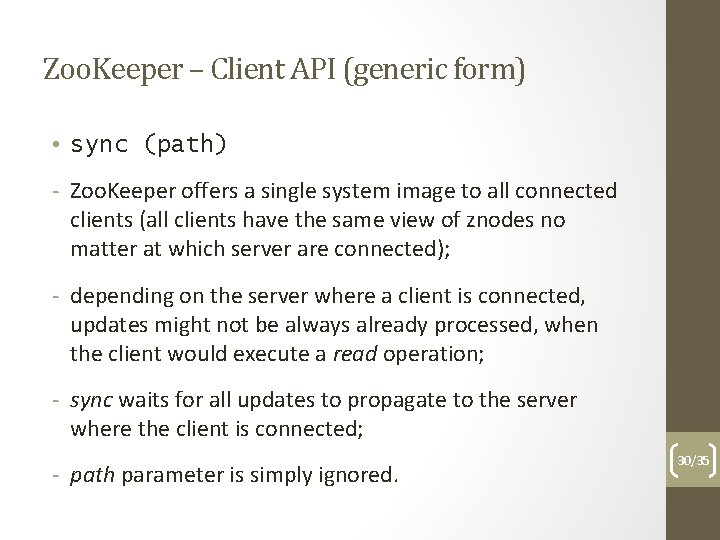

Zoo. Keeper – Client API (generic form) • sync (path) - Zoo. Keeper offers a single system image to all connected clients (all clients have the same view of znodes no matter at which server are connected); - depending on the server where a client is connected, updates might not be always already processed, when the client would execute a read operation; - sync waits for all updates to propagate to the server where the client is connected; - path parameter is simply ignored. 30/35

Zoo. Keeper – Client API All operations of read and write type (not the sync), have two forms: • synchronous • execute a single operation and block until this is finalized • does not permit other concurrent tasks • asynchronous • sets a callback for the invoked operation, which is triggered when the operation completes • does permit concurrent tasks • an order guarantee is preserved for asynchronous callbacks based on their invocation order 31/35

Zoo. Keeper – Example scenario Context (use of ZK, not ZK itself): • Distributed applications that have a leader among them responsible with their coordination • While the leader changes system configuration, none of the apps should start using the configuration being changed • If the leader dies before finishing changing configuration, none of the apps should use the unfinished configuration 32/35

Zoo. Keeper – Example scenario How it’s done (using ZK): • The leader designates a /ready path node as flag for ready-to-use configuration, monitored by other apps • While changing configuration the leader deletes the /ready node, and creates it back when finished • FIFO ordering guarantees that apps are notified by the /ready node creation, only after configuration is finished Looks ok. . . or not? 33/35

Zoo. Keeper – Example scenario Q: What if one app sees /ready just before being deleted and starts reading the configuration while being changed? A: The app will be notified when /ready is deleted, so it knows new configuration is being set up, and old one is invalid. It just needs to reset the (one-time triggered) watch on /ready to find out when is created. Q: What if one app is notified by a configuration change (node /ready deleted), but the app is slow and until setting a new watch, the node is already created and deleted again? A: Target of app’s action is reading/using an actual valid state of configuration (which can be, and is, the latest). Missing previous valid versions should not be critical. 34/35

Questions? 35/35

- Slides: 35