Ethical Theory and the Value of Friendship Associate

- Slides: 23

Ethical Theory and the Value of Friendship Associate Professor Justin Oakley, Centre for Human Bioethics, Monash University

Outline Utilitarians have given both psychological and empirical arguments claiming to justify the place of friendship within a life governed by Utilitarian principles: 1. Empirical arguments: Having friendships maximises expected utility. 2. Psychological arguments: Regulating one’s personal relationships by utilitarian or consequentialist dispositions will not be found alienating by one’s ‘friends’. Are these compelling Utilitarian arguments for the place of friendship in an ethical life?

Aristotle on the value of friendship Aristotle argues that humans are social creatures, and that we cannot flourish without friends. The best form of friendship, according to Aristotle, is that between two virtuous people, who take pleasure in their shared commitment to virtue, and who help each other maintain and even improve their virtuousness (see Nicomachean Ethics, Books VIII and IX). 3

Utilitarianism holds that a person acted rightly if what they did could reasonably be expected to result in more happiness (or to maximise the satisfaction of preferences) than anything else which they could have done in the circumstances. The general doctrine of Utilitarianism: A practice is right if and only if it can reasonably be expected to produce the most utility, compared to its alternatives. 4

Utilitarianism: Bentham and the Panopticon

Friendship and Utilitarian purposes Francis H. Bradley argued that utilitarianism tells us to make maximising the good the purpose of every action we perform, and that prevents us from having the goods of spontaneity: “So far as my lights go, this is to make possible, to justify, and even to encourage, an incessant practical casuistry; and that, it need scarcely be added, is the death of morality” (Bradley, p. 107). (See Williams, p. 128) Similarly, it is often argued that acting for the sake of maximising the good is incompatible with friendship, since it is part of the meaning of an act of friendship that it is done for the sake of the friend. Does this show that good Utilitarians cannot consistently have friendships? 6

Henry Sidgwick on Utilitarianism as a motive vs. Utilitarianism as only a criterion of rightness The concern to maximise utility can guide us through being our motive for action, rather than as the purpose of our action. The good Utilitarian agent need not (or not always) in their actions aim at maximising utility. Indeed, as Henry Sidgwick suggests: “It seems true that Happiness is likely to be better attained if the extent to which we set ourselves consciously to aim at it be carefully restricted” (405). “The doctrine that Universal Happiness is the ultimate standard must not be understood to imply that Universal Benevolence is the only right or always best motive of action. For. . . it is not necessary that the end which gives the criterion of rightness should always be the end at which we consciously aim: and if experience shows that the general happiness will be more satisfactorily attained if men frequently act from other motives than pure universal philanthropy, it is obvious that these other motives are reasonably to be preferred on Utilitarian principles” (413). 7

John Stuart Mill “It is a misapprehension of the utilitarian mode of thought, to conceive it as implying that people should fix their minds upon so wide a generality as the world, or society at large. The great majority of good actions are intended not for the benefit of the world, but for that of individuals, of which the good of the world is made up…. The multiplication of happiness is, according to the utilitarian ethics, the object of virtue: the occasions on which any person (except one in a thousand) has it in his power to do this on an extended scale, in other words to be a public benefactor, are but exceptional; and on these occasions alone is he called on to consider public utility; in every other case, private utility, the interest or happiness of some few persons, is all he has to attend to”(270). 8

Albert Schweitzer Let no one say: ‘Suppose "the Fellowship of those who bear the Mark of Pain" does by way of beginning send one doctor here, anothere, what is that to cope with the misery of the world? ’ From my own experience and from that of all colonial doctors, I answer, that a single doctor out here with the most modest equipment means very much for very many. The good which he can accomplish surpasses a hundredfold what he gives of his own life and the cost of the material support which he must have. Just with quinine and arsenic for malaria, with novarseno-benzol for the various diseases which spread through ulcerating sores, with emetin for dysentery, and with sufficient skill and apparatus for the most necessary operations, he can in a single year free from the power of suffering and death hundreds of men who must otherwise have succumbed to their fate in despair. It is just exactly the advance of tropical medicine during the last fifteen years which gives us a power over the sufferings of the men of far-off lands that borders on the miraculous. Is not this really a call to us? (Schweitzer 1949, p. 127) 9

Utilitarianism and Effective Altruism 10

Empirical arguments for why Utilitarians can have friendships R. M. Hare: “If we were concerned impartially for the good of all children, we should want mothers to behave partially toward their own children and have feelings which made them behave in this way. We should want this because, if mothers are like this, children will be better looked after than if mothers tried to feel the same about other people’s children as about their own”(31). 11

Frank Jackson on the nearest and dearest objection “. . . the good consequentialist should focus her attentions on securing the well-being of a relatively small number of people, herself included, not because she rates their welfare more highly than the welfare of others, but because she is in a better position to secure their welfare. . [S]he knows, if she is at all like most of us, that the chances of success are much greater if she makes the relatively small group those who are her family and friends, rather than those she hardly knows”(481). 12

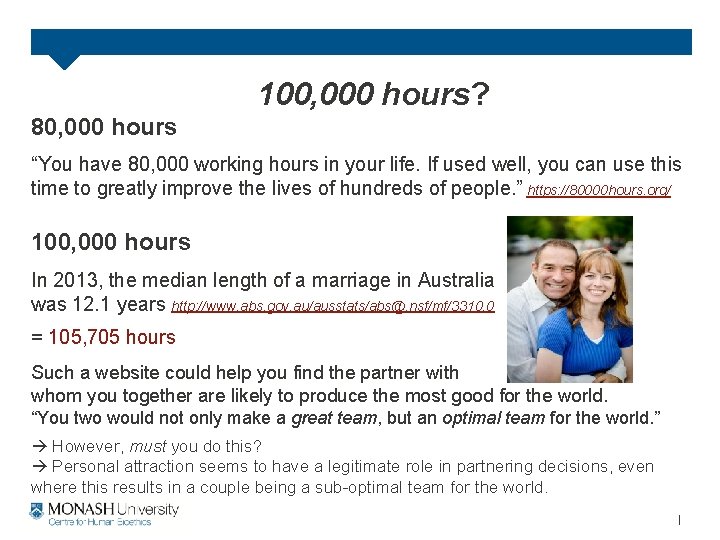

100, 000 hours? 80, 000 hours “You have 80, 000 working hours in your life. If used well, you can use this time to greatly improve the lives of hundreds of people. ” https: //80000 hours. org/ 100, 000 hours In 2013, the median length of a marriage in Australia was 12. 1 years http: //www. abs. gov. au/ausstats/abs@. nsf/mf/3310. 0 = 105, 705 hours Such a website could help you find the partner with whom you together are likely to produce the most good for the world. “You two would not only make a great team, but an optimal team for the world. ” However, must you do this? Personal attraction seems to have a legitimate role in partnering decisions, even where this results in a couple being a sub-optimal team for the world.

Psychological arguments about whether Utilitarians can have friendships – without alienation from friends 14

Michael Stocker on the schizophrenia of modern ethical theories “Suppose you are in hospital, recovering from a long illness. You are very bored and restless and at loose ends when Smith comes in once again. You are now convinced more than ever that he is a fine fellow and a real friend - taking so much time to cheer you up, traveling all the way across town, and so on. You are so effusive with your praise and thanks that he protests that he always tries to do what he thinks is his duty, what he thinks will be best. You at first think he is engaging in a polite form of self-deprecation, relieving the moral burden. But the more you two speak, the more clear it becomes that he was telling the literal truth: that it is not essentially because of you that he came to see you, not because you are friends, but because he thought it his duty, perhaps as a fellow Christian or Communist or whatever, or simply because he knows of no one more in need of cheering up and no one easier to cheer up”(462). 1

Peter Railton on how consequentialists can avoid alienating their friends As a "sophisticated consequentialist", Juan's motivational structure should meet a counterfactual condition: while he ordinarily does not do what he does for the sake of doing what's right, he would nevertheless alter his dispositions and the course of his life if he thought they did not most promote the good (see pp. 105, 111). Thus, Juan is prepared to leave Linda if maximising the good requires him to do so: "What Juan recognizes to be morally required is not by its nature incompatible with acting directly for the sake of another. It is important to Juan to subject his life to moral scrutiny. . . His love is not a romantic submersion in the other to the exclusion of worldly 16

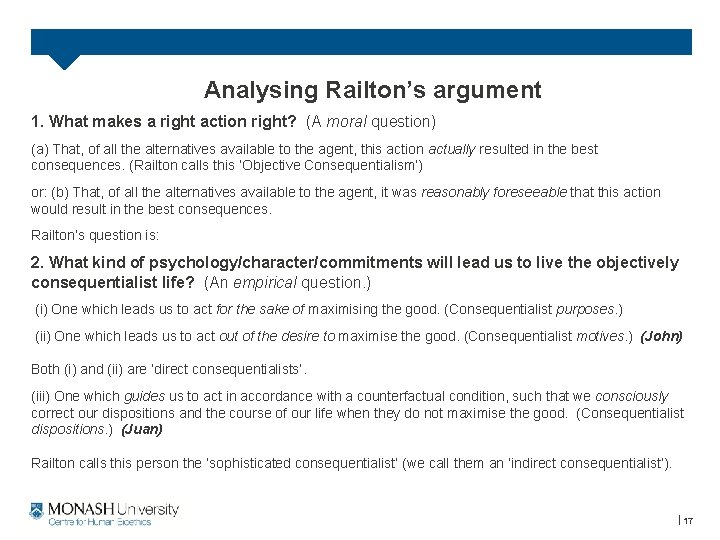

Analysing Railton’s argument 1. What makes a right action right? (A moral question) (a) That, of all the alternatives available to the agent, this action actually resulted in the best consequences. (Railton calls this ‘Objective Consequentialism’) or: (b) That, of all the alternatives available to the agent, it was reasonably foreseeable that this action would result in the best consequences. Railton’s question is: 2. What kind of psychology/character/commitments will lead us to live the objectively consequentialist life? (An empirical question. ) (i) One which leads us to act for the sake of maximising the good. (Consequentialist purposes. ) (ii) One which leads us to act out of the desire to maximise the good. (Consequentialist motives. ) (John) Both (i) and (ii) are ‘direct consequentialists’. (iii) One which guides us to act in accordance with a counterfactual condition, such that we consciously correct our dispositions and the course of our life when they do not maximise the good. (Consequentialist dispositions. ) (Juan) Railton calls this person the ‘sophisticated consequentialist’ (we call them an ‘indirect consequentialist’). 17

A rejoinder to Railton 18

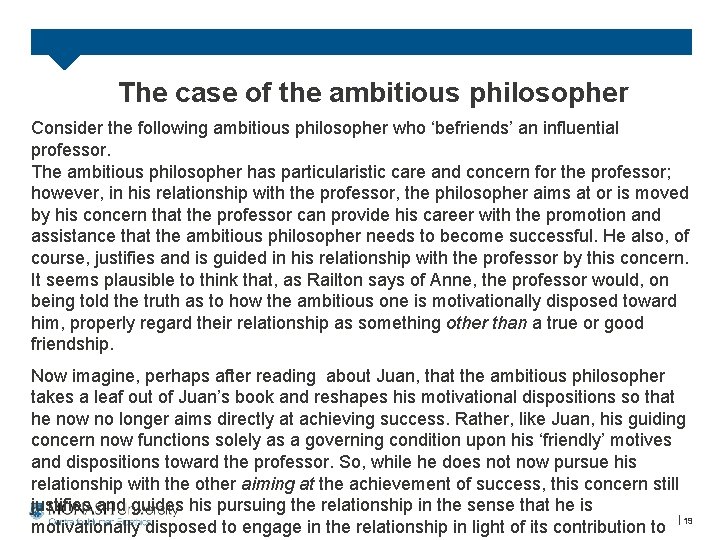

The case of the ambitious philosopher Consider the following ambitious philosopher who ‘befriends’ an influential professor. The ambitious philosopher has particularistic care and concern for the professor; however, in his relationship with the professor, the philosopher aims at or is moved by his concern that the professor can provide his career with the promotion and assistance that the ambitious philosopher needs to become successful. He also, of course, justifies and is guided in his relationship with the professor by this concern. It seems plausible to think that, as Railton says of Anne, the professor would, on being told the truth as to how the ambitious one is motivationally disposed toward him, properly regard their relationship as something other than a true or good friendship. Now imagine, perhaps after reading about Juan, that the ambitious philosopher takes a leaf out of Juan’s book and reshapes his motivational dispositions so that he now no longer aims directly at achieving success. Rather, like Juan, his guiding concern now functions solely as a governing condition upon his ‘friendly’ motives and dispositions toward the professor. So, while he does not now pursue his relationship with the other aiming at the achievement of success, this concern still justifies and guides his pursuing the relationship in the sense that he is motivationally disposed to engage in the relationship in light of its contribution to 19

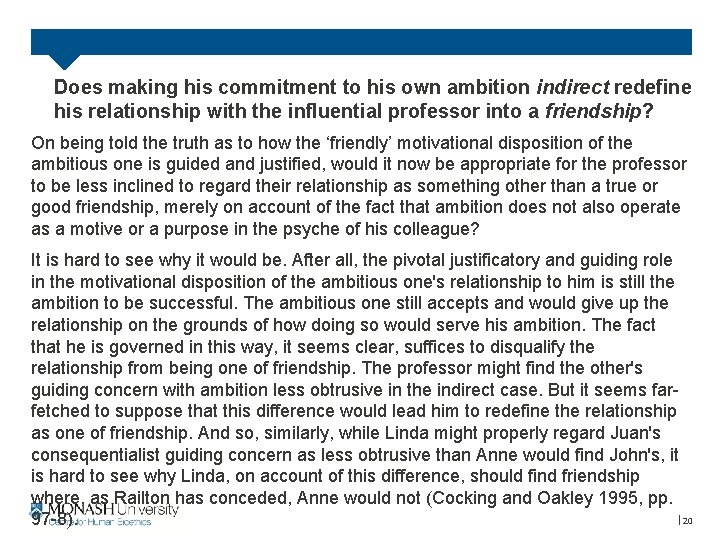

Does making his commitment to his own ambition indirect redefine his relationship with the influential professor into a friendship? On being told the truth as to how the ‘friendly’ motivational disposition of the ambitious one is guided and justified, would it now be appropriate for the professor to be less inclined to regard their relationship as something other than a true or good friendship, merely on account of the fact that ambition does not also operate as a motive or a purpose in the psyche of his colleague? It is hard to see why it would be. After all, the pivotal justificatory and guiding role in the motivational disposition of the ambitious one's relationship to him is still the ambition to be successful. The ambitious one still accepts and would give up the relationship on the grounds of how doing so would serve his ambition. The fact that he is governed in this way, it seems clear, suffices to disqualify the relationship from being one of friendship. The professor might find the other's guiding concern with ambition less obtrusive in the indirect case. But it seems farfetched to suppose that this difference would lead him to redefine the relationship as one of friendship. And so, similarly, while Linda might properly regard Juan's consequentialist guiding concern as less obtrusive than Anne would find John's, it is hard to see why Linda, on account of this difference, should find friendship where, as Railton has conceded, Anne would not (Cocking and Oakley 1995, pp. 20 97 -8).

Some possible replies by Consequentialists? 1. So much the worse for friendship? But is this really an attractive option? Railton himself would say not: “We must recognize that loving relationships, friendships, group loyalties, and spontaneous actions are among the most important contributors to whatever it is that makes life worthwhile; any moral theory deserving serious consideration must itself give them serious consideration. . . If we were to find that adopting a particular morality led to irreconcilable conflict with central types of human well being. . , then this surely would give us good reason to doubt its claims” (pp. 98 -9). 2. Try to show friendship is compatible with the governing conditions of a consequentialist regulative ideal. So, in what other ways might a person live the objectively consequentialist life? And, are any of these compatible with friendship? 21

Are other ways of living an objectively consequentialist life compatible with friendship? In what other ways might a person live the objectively consequentialist life? And, are any of these compatible with friendship? Consider the following sorts of character: (iv) One which guides us to act in accordance with a counterfactual condition, such that we unconsciously correct our dispositions and the course of our life when they do not maximise the good. (Consequentialist dispositions. ) (Raul) (v) One where it is counterfactually true of us that we would change in ways consistent with objective consequentialism, but we are not guided (either consciously or unconsciously) by consequentialism to do so. (Here the consequentialist criterion of rightness is ‘esoteric’. ) 22

References and further reading Jeremy Bentham, An Introduction to the Principles of Moral and Legislation, New York, Hafner, 1948. F. H. Bradley, Ethical Studies, Oxford, Clarendon Press, 1962. Dean Cocking and Justin Oakley, ‘Indirect Consequentialism, Friendship, and the Problem of Alienation’, Ethics 106, no. 1, October 1995, pp. 86 -111. Dean Cocking and Jeanette Kennett, ‘Friendship and Moral Danger’ Journal of Philosophy 97, no. 5, May 2000, pp. 278 -296. Earl Conee, ‘Friendship and Consequentialism’, Australasian Journal of Philosophy 79, no. 2, June 2001, pp. 161179. R. M. Hare, Methods of Bioethics: Some Defective Proposals, in. L. W. Sumner and Joseph Boyle (eds. ), Philosophical Perspectives on Bioethics, eds. L. W. Sumner and Joseph Boyle, Toronto, University of Toronto Press, 1996. Frank Jackson, ‘Decision-Theoretic Consequentialism and the Nearest and Dearest Objection’, Ethics 101, 1991, pp. 461 -482. Simon Keller, Partiality, Princeton University Press, 2013. William Mac. Askill, Doing Good Better, New York, Penguin, 2015. Elinor Mason, ‘Can an Indirect Consequentialist be a Real Friend? ’ Ethics 108, no. 2, January 1998, pp. 386 -393. John Stuart Mill, Utilitarianism (ed. Mary Warnock), Cleveland, Meridian Books, 1962. Justin Oakley and Dean Cocking, Virtue Ethics and Professional Roles, Cambridge University Press, 2001. Justin Oakley and Dean Cocking, ‘Consequentialism, complacency, and slippery slope arguments’, Theoretical Medicine and Bioethics 26, no. 3, May 2005, pp. 227 -39. Justin Oakley, ‘Personal Relationships’, in Hugh La. Follette (ed. ), International Encyclopedia of Ethics, Cambridge MA: Wiley-Blackwell, 2013, pp. 3851 -3864. Justin Oakley, ‘Virtue ethics and utilitarianism’, in Stan van Hooft (ed. ), The Handbook of Virtue Ethics, Durham, Acumen, 2014, pp. 64 -75. Peter Railton, ‘Alienation, Consequentialism, and the demands of morality’, Philosophy and Public Affairs 13, no. 2, Spring 1984, pp. 134 -171. Albert Schweitzer, On the Edge of the Primeval Forest (trans. C. T. Campion), London, A&C Black, 1949. Henry Sidgwick, The Methods of Ethics, 7 th ed. , Indianapolis, Hackett, 1980. J. J. C. Smart and Bernard Williams, Utilitarianism: For and Against, Cambridge University Press, 1973. Michael Stocker, ‘The schizophrenia of modern ethical theories’, Journal of Philosophy 73, no. 14, 1976, pp. 453466. Scott Woodcock, ‘Moral schizophrenia and the paradox of friendship’, Utilitas 22, no. 2, March 2010, pp. 1 -25.